Incidence of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Children in Haji Adam Malik

Hospital Medan

Selvi Nafianti, Nelly Rosdiana, dan Bidasari Lubis

Division Hematology-Oncology Child Health Department Medical Faculty University of Sumatera Utara / Haji Adam Malik Hospital Medan Indonesia

ackground: Leukemia is the most common malignancy in childhood and about 15 percent of childhood leukemia cases are acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). It is reported in more than 13,000 people newly diagnosed each year. The overall survival rate has reached a plateau at approximately 60%, suggesting that further intensification of therapy per se will not substantially improve survival rates. Methods: This study was retrospective with all the children who came to Division Hematology-Oncology Haji Adam Malik Hospital during January 2001 - December 2006 with diagnosis Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) were enrolled to this study. The diagnosis of AML was established based on morphology. There were 45 children meet the criteria. Results: in our study there were 25 boys and 20 girls. Age range 1-14 years (median age 9 yrs). Most patient were in group age more than 10 years old, followed by group age 1-5 and 5-10 years as much as 13 cases each. There were 14 children suffered from severe malnutrition, 13 mild malnutrition and 13 moderate malnutrition. There were total of 39 patient had chemotherapy, and 6 patient refused to have chemotherapy with one and another reason. Only 6 from 45 were survival, death in 20 cases mostly in induction phase 10 cases, consolidation 7 cases and maintenance 3 cases. There were 19 cases who refused to follow the chemotherapy protocol. Conclusion: AML is remain a major problem in developing countries. Incidence may vary due to the limitation of diagnostic tool and prognosis was still bad.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, children

INTRODUCTION

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), also known as acute myelogenous or acute myeloblastic leukemia, is a type of cancer that starts from cells that normally develop into blood cells.1-5

AML mainly develops from two types of white blood cells: granulocytes or monocytes. AML is caused by genetic damage to these developing cells in the bone marrow. The result is uncontrolled growth and accumulation of undeveloped cells called "leukemic blasts," which fail to function as normal blood cells. As these cells accumulate, they block the production of normal marrow cells, leading to a deficiency of red cells, blood-clotting platelets and normal infection-fighting white cells.6-8

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the most common form of leukemia with more than 13,000 people diagnosed each year, according to National Cancer Institute estimates. About 15 percent of childhood leukemia cases are AML. Older individuals, however, are more likely to

develop the disease. The median age at diagnosis is 67. Of those with AML, less than 6 percent are younger than 20 when diagnosed; more than 55 percent are diagnosed at 65 or older. About 0.38 percent of people will be diagnosed with AML during their lifetimes.9-12

Each year in the United States 500 to 600 individuals younger than 21 years develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Current treatment for AML typically consists of 3 or 4 courses of intensive, myelosuppressive chemotherapy with or without bone marrow transplantation from a histocompatible family donor.This therapy cures about half the children with AML; of the other half, most succumb to AML-related causes, but 5% to 15% die from toxic effects of treatment.13-16

The cause of AML is unknown.17-23

chemical benzene and exposure to chemotherapy. Smoking is another proven risk factor, which causes about 1 in 5 cases of AML. Uncommon genetic disorders, such as Fanconi anemia and Down syndrome, are associated with an increased risk of AML. Identifying risk factors for childhood leukemia (e.g., environmental, genetic, infectious) is an important step in the reduction of the overall burden of the disease. In general, benzene and ionizing radiation are two environmental exposures strongly associated with the development of childhood AML or ALL. Future studies, when appropriate, should attempt to use common questionnaires, address timing and route of exposure, document evidence that exposure has actually been transferred from the workplace to the child, and store biological samples when possible. Scheneider et al3

, reported in patients with AML after treatment for Germ cell tumor (GCT), several pathogenetic mechanisms must be considered. AML might evolve from a malignant transformation of GCT components without any influence of the chemotherapy. On the other hand, the use of alkylators and topoisomerase II inhibitors is associated with an increased risk of t-AML. Future studies will show if the reduction of treatment intensity in the current protocol reduces the risk of secondary leukemia in these patients.5-8

A combination of morphologic, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic studies is usually required to establish the diagnosis of AML. Immunophenotype is important, particularly in establishing a diagnosis of acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL), myeloid leukemia with minimal differentiation, and myeloid/lymphoid (mixed, biphenotypic) leukemia. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO), in conjunction with the Society for Hematopathology and the European Association of Hematopathology, has proposed a new classification for hematopoietic neoplasms. The WHO classification defines subsets of AML on the basis of both morphologic and cytogenetic characteristics. Although the current AML classification schemes, including the WHO scheme, have been developed for adult AML, the concepts underlying these classifications can be applied to pediatric AML. Recent gene

expression profiling studies demonstrated distinct expression signatures for each of the known prognostic subtypes of AML. Importantly, some of the pediatric AML subtype specific expression signatures were essentially the same as those of selected adult AML cases, suggesting a shared leukemogenesis.8-14

Creutzig U et al11

obstacle to effective AML treatment. The rates of early death (ED) and treatment-related mortality (TRM) are unacceptably high in children undergoing intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Better strategies of supportive care might help to improve overall survival in these children.7-13

METHODS

This was a retrospective study, we review all the children who came to Division Hematology-Oncology Haji Adam Malik Hospital during January 2001 - December 2006 with diagnosis Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) were enrolled to this study. The diagnosis of AML was established based on morphology. There were 45 children meet the criteria.

RESULTS

Table 1. Characteristic of study subject

N=45

Sex

Boys 25

Girls 20

Age group (years)

< 1 2

1 – 5 13

5 – 10 13

> 10 17

Nutritional State

Normal 5

Mild 13

Moderate 13

Severe 14

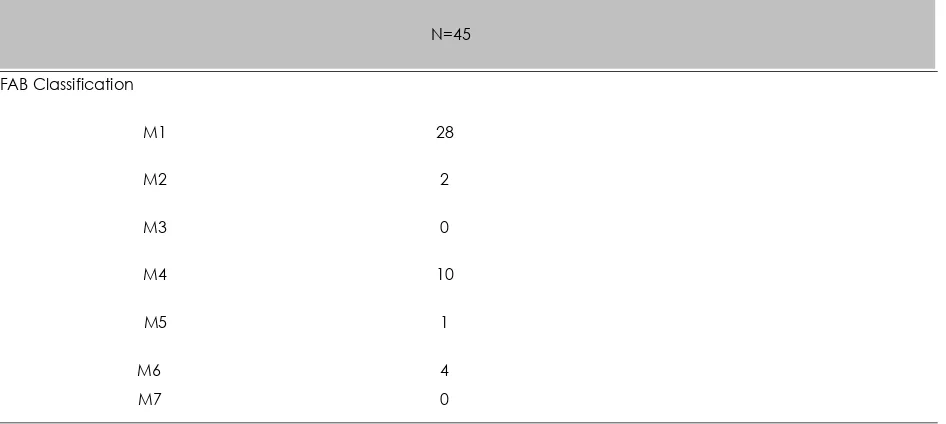

Table 2. Distribution sample based on FAB Classification

N=45

FAB Classification

M1 28

M2 2

M3 0

M4 10

M5 1

M6 4

Table 3. Chemotherapy

N=45

Chemotherapy phase

Induction 17

Consolidation 12

Maintenance 10

Discontinued 6

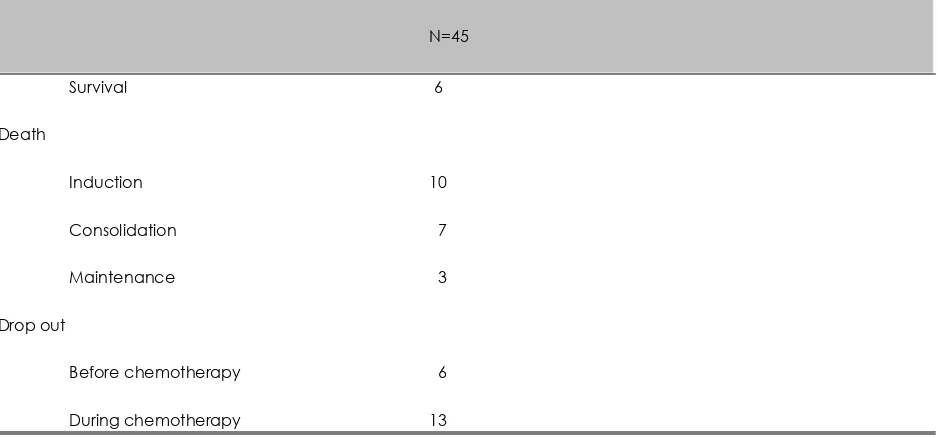

Table 4. Treatment outcome

N=45

Survival 6

Death

Induction 10

Consolidation 7

Maintenance 3

Drop out

Before chemotherapy 6

During chemotherapy 13

Table 1 showed that in our study there were 25 boys and 20 girls. Most patient were in group age more than 10 years old, followed by group age 1-5 and 5-10 years as much as 13 cases each. There were 14 children suffered from severe malnutrition, 13 mild malnutrition and 13 moderate malnutrition.

From table 3, found that there were total of 39 patient had chemotherapy, and 6 patient refused to have chemotherapy with one and another reason

Only 6 from 45 were survival, death in 20 cases mostly in induction phase 10 cases, consolidation 7 cases and maintenance 3 cases. There were 19 cases who refused to follow the chemotherapy protocol.

DISCUSSION

undernutrition in other pediatric cancers. Interventions currently available that could reduce the treatment related mortality in underweight and overweight groups include formal nutritional and immunologic assessment at diagnosis. Underweight patients could benefit from preemptive nutritional intervention or intravenousglobulin. In overweight patients, correction of persistent moderate hyperglycemia and hypertension may remediate 2 important comorbidities. Lange et al15

, in their study to compare survival rates in children with AML who at diagnosis are underweight (body mass index [BMI] _10th percentile), overweight (BMI _95th percentile), or middleweight (BMI = 11th-94th percentiles). Eighty-four of 768 patients (10.9%) were underweight and 114 (14.8%) were overweight. After adjustment for potentially confounding variables of age, race, leukocyte count, cytogenetics, and bone marrow transplantation, compared with middleweight patients, underweight patients were less likely to survive and more likely to experience treatment related mortality. Similarly, overweight patients were less likely to survive and more likely to have treatment-related mortality than middleweight patients. Infections incurred during the first 2 courses of chemotherapy caused most treatment-related deaths. The study noted that treatment-related complications significantly reduce survival in overweight and underweight children with AML. Becton et al16

, reported that intensifying induction with high-dose DAT and the addition of CsA to consolidation chemotherapy did not prolong the durations of remission or improve overall survival for children with AML. O’Brian et al17

, found that improvements in remission-induction rates, decreased treatment related toxicity, and improved outcomes with allogeneic sibling transplantation have contributed to higher survival rates. Nevertheless, further improvements are needed. Unlike AML trials in adults, AML in children results do not support an advantage of idarubicin over daunorubicin in the treatment of pediatric AML in terms of remission induction or overall survival rates. In addition, it’s found greater toxicity with idarubicin than with daunorubicin.

Creutzig et al, found that idarubicin when used for remission induction in childhood AML was associated with more bone marrow toxicity, with a greater number of days to neutrophil recovery, than patients treated with daunorubicin. The study shown that greater renal, gastrointestinal, and pulmonary toxicity occurred in patients receiving idarubicin during remission induction. Gastrointestinal toxicity in our patient group was dose related and entailed significantly more toxicity in patients receiving the higher dosage of idarubicin. This may reflect different pharmacokinetic parameters in pediatric patients than those used in previously published studies in adults. No difference in acute cardiotoxicity was noted, but long-term follow-up is needed to establish any evidence of benefit that idarubicin may provide in that regard.

making them more susceptible to cytarabine and other cell-cycle–specific agents.

AML is the most common leukaemia seen in children with Down’s syndrome. The risk of increased deaths from infection during induction and remission means that there has to be very good supportive and nursing care. There must also be extreme vigilance as these children are vulnerable to life-threatening infections during their treatment although they do have a very good chance of cure and a very low risk of relapse. AML in children with Down’s syndrome is quite an indolent disease. Clinical problems may be slow to children with Down’s syndrome and AML respond unusually well to intensive treatment. The need for aggressive cytotoxic chemotherapy has been questioned and debated worldwide. Some do well on less intensive regimens but some die. An international trial would be necessary to establish whether it is indeed safe to use less intensive protocols. In the early days of the AML trials, four children with Down’s syndrome had bone marrow transplants (BMT). However the excellent response to intensive cytotoxic therapy which is now reported suggests that BMT should no longer be necessary for any child with Down’s syndrome. Children with Down’s syndrome get a unique form of myeloid leukaemia – megakaryoblastic leukaemia – which is extremely rare in other children. It is very sensitive to agressive chemotherapy, which gives a high chance of cure. BMT is not needed as these children do very well on chemotherapy. Gujral et al18

, concluded that diagnosticwork-up of proptosis must include a full haemogram, meticulous peripheral blood smear examination, repeated if necessary, and bone marrow examination where relevant. Refractory anaemia with excess blasts in transformation (RAEB-t ) cases with extramedullary myeloid cell tumour should be classified as acute myeloid leukaemia.

Ziegler et al19

, suggested that much has changed over the past decade in front-line treatment, identifying relapse risk and in our understanding of leukaemogenesis in AML. The genome revolution, molecular drug targeting and computer-aided drug design techniques will reshape this field yet again over the next decade in ways which may allow

for further individualisation of therapy to enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity. Perel et al20

, reported that more than 50% of patients can be cured of AML in childhood. Either drug intensity or each of the induction and postremission phases may have contributed to the outstanding improvement in outcome. Lowdose MT is not recommended. Exposure to this lowdose MT may contribute to clinical drug resistance and treatment failure in patients who experience relapse.

Abrahamsson et al21

found the survival was 62±6% in 64 children given stem cell transplantation (SCT) as part of their relapse therapy. A significant proportion of children with relapsed AML can be cured, even those with early relapse. Children who receive re-induction therapy, enter remission and proceed to SCT can achieve a cure rate of 60%.

Creutzig et al22

, found that late subclinical cardiomyopathy occurred temporarily in seven patients. The risk of developing late clinical cardiotoxicity was highest in patients with early cardiotoxicity and in patients with secondary malignancy. The investigators concluded that the frequency of anthracycline- associated cardiomyopathy was low in patients treated on the AML-BFM protocols. Leung et al23 concluded that late sequelae are common in long-term survivors of childhood AML. Our findings should be useful in defining areas for surveillance of and intervention for late sequelae and in assessing the risk of individual late effects on the basis of age and history of treatment. To reduce the high incidence of ED and TRM in children with AML, early diagnosis and adequate treatment of complications are needed. Children with AML should be treated in specialized pediatric cancer centres only. Prophylactic and therapeutic regimens for better treatment management of bleeding disorders and infectious complications have to be assessed in future trials to ultimately improve overall survival in children with AML.

REFERENCE

2. Hjalgrim LL, Rostgaard K, Schmiegelow K, So¨derha¨ll K, Kolmannskog K, Vettenranta K, et al. Age- and Sex-Specific Incidence of Childhood Leukemia by Immunophenotype in the Nordic Countries. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95:1539–44.

3. Scneider DT, Hilgenfeld E, Schwabe D, Behnisch W, Zoubek A, Wessalowski R, Go’’bel. Acute myelogenous leukaemia after treatment for malignant germ cell tumors in children. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3226-33.

4. Xie Y, Davies SM, Xiang Y, Robinson LL, Ross JA. Trends in leukaemia incidence and survival in the United States (1973-1998). Cancer 2003;97:2229-35.

5. Mejía-Aranguré JM, Bonilla M, Lorenzana R, Juárez-Ocaña S, de Reyes G, Pérez-Saldivar ML, et al. Incidence of leukemias in children from El Salvador and Mexico City between 1996 and 2000: Population-based data. BMC Cancer 2005; 5:33. 6. Chessells J. Blood disorder in children

with Down’s syndrome: overview and update. Presented in Blood Disorder Conference. London 26th

April 2001. 7. Belson M, Kingsley B, Holmes A. Risk

factors for acute leukemia in children: A review. Environ Health Perspect 2006;115:138-45.

8. Hegedus CM, Gunn L, Skibola CF, Zhang L, Shiao R, Fu S, et al. Proteomic analysis of childhood leukemia. Leukemia 2005; 19:1713-8.

9. Pui CH, Schrappe M, Ribeiro RC, Niemeyer CM. Childhood and adolescent lymphoid and myeloid leukemia. Hematol 2004:118-45.

10. Lowenberg B, Downing JR, Burnett A. Acute myeloid leukemia. NEMJ 1999; 341(14):1051-62.

11. Creutzig U. Treatment strategy and long-term results in pediatric patients treated in four consecutive AML-BFM trials. Leukemia 2005; 19: 2030–42.

12. Weinstein HJ. Acute myeloid leukemia. In: Pui CH, ed. Childhood leukemias. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. p. 322-5.

13. Locatelli F, Labopin M, Ortega J, Meloni G, Dini G, Messina C, et al. Factors influencing outcome and incidence of long-term complications in children who underwent autologous stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission for the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Acute Leukemia Working Party. Blood. 2003; 101:1611-1619. 14. Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt

D, Dworzak M, Stary J, Lehrnbecher T. Early deaths and treatment realted mortality in children undergoing therapy for acute myeloid leukemia: Analysis of the multicenter clinical trials AML-BFM 93 and AML-BFM 98. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22:4384-93.

15. Lange BJ, Gerbing RB, Feusner J, Skolnik J, Sacks N, Smith FO, Alonzo TA. Mortality in overweight and underweight children with acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA 2005; 293:203-211.

16. Becton D, Dahl GV, Ravindranath Y, Chang MN, Behm FG, Raimondi SC, et al. Randomized used of cyclosporine A (CsA) to modulate P-glycoprotein in children with AML in remission: Pediatric oncology group study 9421. Blood 2006; 107:1315-24.

17. O’Brien TA, Russel SJ, Vowels MR, Oswald CM, Tiedemann K, Shaw PJ, et al. Results of consecutive trials for children newly diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia from the Australian and New Zeland chlidren’s cancer study group. Blood 2002; 100:2708-16.

18. Gujral S, Bhattari S, Mohan A, Jain Y, Arya LS, Ghose S, et al. Brief report. Ocular extramedullary myeloid cell tumour in children: an Indian study. J Trop Paediatr 1999; 45(2):112-5.

20. Ziegler DS, Pozza LD, Waters KD, Marshall GM. Advances in childhood leukaemia: successful clinical-trials research leads to individualised therapy. MJA 2005; 182 (2): 78-81.

21. Abrahamsson J, Clausen N, Gustafsson G, Hovi L, Jonmundsson G, Zeller B, et al. Improved outcome after relapse in children with acute myeloid leukemia. B J Haematol 2007; 136(2):229-36.

22. Creutzig U, Zimmerman DS.

Longitudinal evaluation of early and late anthracycline cardiotoxicity in children with AML. Pedaitr Blood Cancer 2007; 48:651-62.