Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 19:47

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Survey of recent developments

Ross H. Mcleod

To cite this article: Ross H. Mcleod (2005) Survey of recent developments, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 41:2, 133-157, DOI: 10.1080/00074910500117271 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910500117271

Published online: 18 Jan 2007.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 96

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/05/020133-25 © 2005 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910500117271

SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Ross H. McLeod

Australian National University

SUMMARY

The new government of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) has been performing well relative to the standards of recent governments. The confidence of the busi-ness community in Indonesia’s near-term future continues to improve, resulting in rapid growth of investment activity, steady gains on the stock market, and a return of private capital inflow. City skylines are again decorated with cranes for the construction of apartment buildings, shopping malls and the like, while expenditure on cars and motorcycles, cell phones and air travel is growing rap-idly. The rate of economic growth is now not far below that typically achieved in the Soeharto era.

Macroeconomic management is broadly on the right track. The budget deficit is small enough not to pose a problem of fiscal sustainability and, although the monetary authority continues to make things difficult for itself by pursuing con-flicting targets, prices remain reasonably stable. At the microeconomic level, how-ever, there are still plenty of causes for concern, the most serious of which, perhaps, is the dissipation of Indonesia’s current oil price windfall in wasteful and extraordinarily costly subsidies to domestic consumption, notwithstanding the recent increase in domestic fuel prices.

Little has been achieved in relation to privatisation, and the government has scant enthusiasm for it. Paradoxically, it is encouraging heavy private sector involvement in infrastructure, which would otherwise be provided by state enterprises. Such involvement will be difficult to achieve, partly for the same rea-sons that privatisation has been hindered, but not least because the government has yet to come to grips with the implications for pricing of infrastructure serv-ices if such activities are to be made profitable—a prerequisite for private sector involvement. Problems with infrastructure as they manifest themselves at lower levels of government are illustrated and analysed in this Survey by a short case study of West Java province and its capital city, Bandung.

There has been a great deal of anti-corruption activity, resulting in several high profile arrests. But this falls far short of what is required to achieve significant improvement in the performance of the public sector, broadly defined, on which healthy and sustained growth of the economy depends heavily. The government has been slow to appoint new people to the top levels of the bureaucracy, and reformist ministers have also been frustrated by civil service rules and regula-tions that make it exceedingly difficult to appoint the best available individuals to these and other important positions.

INTRODUCTION

Indonesia has continued to experience more than its share of misfortunes and missteps in the period of this Survey. The earthquake that generated the devas-tating tsunami at the end of 2004 has been followed by numerous additional earthquakes, the most serious of which caused extensive injury, loss of life and destruction of property on the island of Nias off the coast of Sumatra late in March. Malaysia and Indonesia became involved in a territorial dispute over a part of the Sulawesi Sea thought to contain oil reserves. There has been an out-break of polio in the provinces of Banten and West Java, to which the authorities have responded with mass immunisations of infants and young children. The uneasy peace between Christians and Muslims in Central Sulawesi was jolted, if not broken, by two bombs that injured scores of people and claimed at least 20 lives in late May. Huge new financial losses at the state-owned Bank Mandiri began to be revealed in May, and officials of the election commission were arrested on charges of corruption in relation to procurement activity. Even the religious affairs ministry has been hit with corruption allegations in relation to the management of funds for the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca. At the same time, there has been increasing disquiet at the apparent inability of the authorities to make any headway in the case of the September 2004 murder of the respected human rights activist, Munir.

On the other hand, the political scene has been relatively benign, largely as a result of vice president Jusuf Kalla’s election as head of the Golkar party, which has had the effect of protecting the government from the threat of serious chal-lenge within the House of Representatives (DPR). The president himself has been successful both at home and overseas in projecting the image of a firm and responsive leader, even if there has been a certain amount of grumbling about the slow pace of reform. His cabinet seems to be functioning reasonably well on the whole, although the possibility has been raised that individual ministers whose performance has been lacklustre might be replaced after the government’s first year in office is completed in October. A post-program monitoring visit by an IMF team during May was all but ignored outside government circles. This was in sharp contrast to the enormous media and financial market attention generated by such teams during the first few years of the crisis, and suggested that the Fund has reverted to the low profile, and more limited, advisory role it played previ-ously. Business confidence was boosted by the takeover in May of the large ciga-rette manufacturer, Sampoerna, by the multinational company, Philip Morris International, in a transaction worth some $5 billion.

MACROECONOMICS

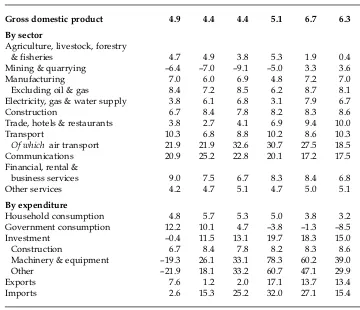

Growth. Preliminary estimates suggest that the economy continued to grow quite strongly, at a rate of about 6.3% year on year, into the first quarter of 2005 (table 1). Rapid growth is now widespread across sectors. The communications sector and the air transport subsector stand out, with extraordinary, sustained growth driven by the rapid adoption of mobile (cell) phones, and strong competition among a plethora of new private sector airlines (GOI 2005a: 13–14). The immense benefits to long-suffering consumers previously restricted to the services provided by state-owned companies such as Garuda and Merpati (airlines) and Telkom

TABLE 1 Components of GDP Growth (2000 prices; % p.a. year-on-year)

Dec-03 Mar-04 Jun-04 Sep-04 Dec-04 Mar-05

Gross domestic product 4.9 4.4 4.4 5.1 6.7 6.3

By sector

Agriculture, livestock, forestry

& fisheries 4.7 4.9 3.8 5.3 1.9 0.4

Mining & quarrying –6.4 –7.0 –9.1 –5.0 3.3 3.6

Manufacturing 7.0 6.0 6.9 4.8 7.2 7.0

Excluding oil & gas 8.4 7.2 8.5 6.2 8.7 8.1

Electricity, gas & water supply 3.8 6.1 6.8 3.1 7.9 6.7

Construction 6.7 8.4 7.8 8.2 8.3 8.6

Trade, hotels & restaurants 3.8 2.7 4.1 6.9 9.4 10.0

Transport 10.3 6.8 8.8 10.2 8.6 10.3

Of which air transport 21.9 21.9 32.6 30.7 27.5 18.5

Communications 20.9 25.2 22.8 20.1 17.2 17.5

Financial, rental &

business services 9.0 7.5 6.7 8.3 8.4 6.8

Other services 4.2 4.7 5.1 4.7 5.0 5.1

By expenditure

Household consumption 4.8 5.7 5.3 5.0 3.8 3.2

Government consumption 12.2 10.1 4.7 –3.8 –1.3 –8.5

Investment –0.4 11.5 13.1 19.7 18.3 15.0

Construction 6.7 8.4 7.8 8.2 8.3 8.6

Machinery & equipment –19.3 26.1 33.1 78.3 60.2 39.0

Other –21.9 18.1 33.2 60.7 47.1 29.9

Exports 7.6 1.2 2.0 17.1 13.7 13.4

Imports 2.6 15.3 25.2 32.0 27.1 15.4

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

1No complaint seems to have been made to the Business Competition Supervisory

Com-mission, whose responsibility it is to try to ensure ‘healthy’ competition among firms to the benefit of consumers (Thee 2002).

line telephones) are obvious, and yet the recent response of the Minister for Trans-port, Hatta Radjasa, has been to announce a mandated increase in air fares, aimed at preventing ‘unfair’ competition in the industry (JP, 2/6/2005),1and an increase

in the minimum requirements for new airline operating licences (JP, 6/6/2005). The trade, hotels and restaurants sector and the transport sector are also register-ing double-digit growth. The large manufacturregister-ing sector has been expandregister-ing at sustained high rates, especially outside oil and gas. Mining and quarrying has moved away from the negative growth rates recorded in 2003 and earlier. The sole exception to this encouraging story is the agriculture, livestock, forestry and

2Money supply growth was reduced to 12–15% p.a. in the five months through April 2005,

compared with 18–23% from April through October 2004. The money aggregate reported here is currency in the hands of the public, which is by far the largest part of base money (i.e. the monetary liabilities of the central bank). Recent data on the latter are difficult to interpret because of the increase in demand for it artificially generated in mid-2004 by non-uniform increases in banks’ required reserve ratios.

3For a discussion of Indonesia’s disappointing inflation performance relative to

neigh-bouring countries, see Fane (2005, in this issue).

fisheries sector, for which year-on-year growth in March fell close to zero. More disaggregated data show that this result is attributable to negative growth of forestry output and, in the two most recent quarters, food crop production.

In contrast with the pattern of the last several years, growth is now being driven by rapid increases in investment spending, as many firms seem to have run up against capacity constraints after several years of low capital expenditure. The bulk of investment is in the form of construction activity, which has been growing robustly, but the growth of spending on machinery and equipment, and ‘other’ capital goods, has been extraordinarily rapid for the last five quarters (table 1). As a result, investment as a proportion of GDP has risen from about 19% to 22%, sig-nificantly closer to the pre-crisis average of around 29%. Increased investment activity is also reflected in a turnaround in private capital flows in the balance of payments: the total was positive in every quarter of 2004, having been negative in every quarter of 2003. Growing confidence in Indonesia’s economic prospects can also be seen in the continuing increase in the Jakarta Stock Exchange composite share price index, which has increased by about 44% since August 2004.

Household consumption has been surprisingly subdued for the last two quar-ters, while government consumption is now clearly a drag on economic growth. Export growth has been high for the last three quarters, while imports have been growing strongly for the last five (table 1), signalling rapidly increasing re-engagement with the world economy. Merchandise exports and imports for the first four months of 2005 are reported to have been 31% and 34% higher, respec-tively, in dollar values, than for the same period in the previous year (JP,

2/6/2005).

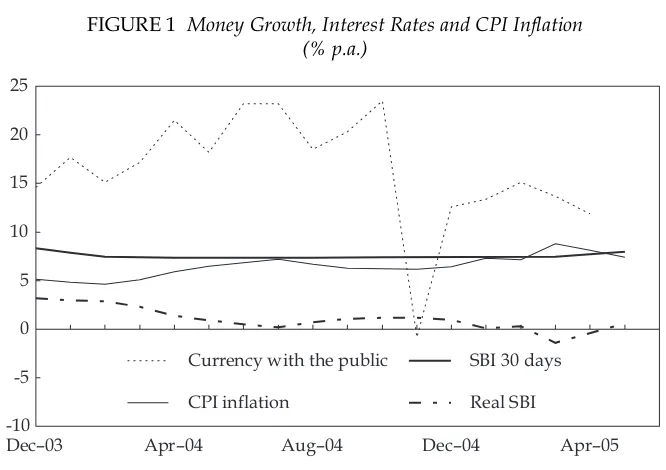

Money and Prices. Monetary policy remains bedevilled by the reality that it is not feasible to have more than a single nominal anchor. As on previous occasions when it has pulled inflation down but failed to keep it at a low level, Bank Indo-nesia’s persistent quest for permanently low nominal interest rates caused it yet again to allow money to grow too rapidly in 2004 and early 2005 (figure 1).2

Infla-tion, which had fallen below 5% in February 2004, began to rise, peaking at almost 9% in March 2005 before the effect of significantly slower monetary growth began to become apparent.3Not surprisingly, the rupiah lost ground

dur-ing the same period: the cost of dollars increased by 15% from the end of 2003 through late April 2005, before recovering somewhat as tighter monetary policy took hold and as confidence in the new government increased. Real interest rates have fallen with increasing inflation. The real 30-day Bank Indonesia Certificate (SBI) rate (approximated by the nominal rate less the contemporaneous inflation rate) was close to zero for the 12 months to May 2005, and nominal rates are now

Dec–03 Apr–04 Aug–04 Dec–04 Apr–05 -10

-5 0 5 10 15 20 25

Currency with the public

CPI inflation

SBI 30 days

Real SBI

FIGURE 1 Money Growth, Interest Rates and CPI Inflation (% p.a.)

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

4Although given considerable emphasis, this item is relatively small—less than Rp 0.5

tril-lion (GOI 2005a: 42–3, 50).

starting to move upward in response to investors’ desire for more strongly posi-tive real rates of return on their savings.

Large increases in fuel prices introduced from the beginning of March have not had a lasting inflationary impact: the inflation rate fell in both April and May as relative prices adjusted throughout the economy. This is a reminder that individ-ual price increases have at most a transient impact on inflation in conditions of slow growth of the money supply.

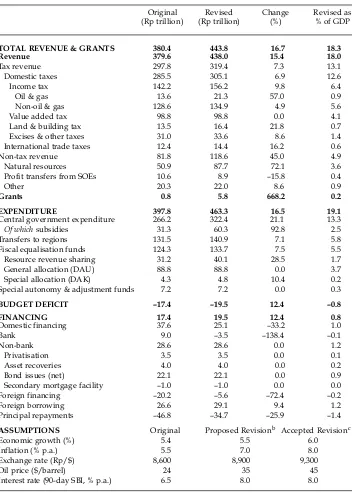

Budget Revision. It is normal practice for the government to introduce a revi-sion to the budget after the outcome for the first semester is reasonably well known. This year, the government introduced a revision several months earlier (GOI 2005a), for a number of reasons. First, the original budget was prepared by the previous government, and did not necessarily reflect the priorities of the new regime. Second, the tsunami and subsequent earthquakes that struck Aceh and North Sumatra have significant budgetary consequences, including increased spending to repair the damage and assist victims, expanded Consultative Group on Indonesia (CGI) assistance, and a moratorium on foreign debt reπpayments offered by the Paris Club. Third, the government is having to incur additional costs in relation to the unexpectedly large number of regional government direct elections being held in 2005.4In addition, world oil prices have been far higher

than projected, while domestically the average exchange rate, inflation rate and interest rate are all likely to be significantly above their originally predicted levels

for the year. All of these movements affect government revenues and expendi-tures.

The proposed revised budget and the adjusted assumptions on which it was based are presented in table 2. Although the size of the revised budget is about 17% larger than the original, the budget deficit as a proportion of GDP remains small and manageable. The new budget was immediately criticised on the grounds that the assumed world oil price and exchange rate averages for 2005 were both unrealistically low, given recent levels of these important prices. Fol-lowing discussions with the DPR the government responded to this criticism by revising all the key macroeconomic assumptions; the revised assumptions are also included in table 2, although the impact of these revisions on the budget had not been revealed at the time of writing.

At the initially proposed revised oil price of $35/barrel, total budget subsidies amounted to over Rp 60 trillion—three times the size of the deficit, and 2.5% of GDP. If actual oil prices turn out closer to the $45/barrel assumption subse-quently agreed with the DPR, the total subsidy will be far higher than even this figure. The government will also earn considerably more revenue from this sec-tor, of course, although much of this will presumably pass to regional govern-ments through the natural resource revenue sharing arrangegovern-ments. The key point here, however, is that a huge proportion of the oil price windfall is still being dis-sipated in wasteful subsidies to fuel consumption, notwithstanding significant domestic fuel price increases introduced in March (box 1). In this regard, it is important to note that that decision was merely to enact a one-off price increase— not to restore the sensible policy (abandoned by the previous government) of automatically adjusting domestic fuel prices in line with developments in the world market.

PRIVATISATION AND PRIVATE SECTOR INVOLVEMENT IN INFRASTRUCTURE

Privatisation

One of the reasons privatisation makes good sense in Indonesia is that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are so vulnerable to abuse. They have always been used as cash cows, purchasing their inputs at marked-up prices, and selling their outputs on the cheap, in utterly non-transparent transactions (Witular 2005a). State-owned financial institutions have been used as sources of cheap finance, provided on inadequate security; the recent scandal at Bank Mandiri (the largest of the state banks) is merely the latest manifestation of this (JP, 4/5/2005). And SOEs have been used by successive governments as a means of buying support by providing jobs at all levels to the favoured few. There is, therefore, strong resistance to privatisation on the part of those who have corruptly benefited from this system of abuse, and from those who hope to benefit from it in the future.

Such people find enthusiastic allies in the ranks of various NGOs and among members of the general public who, while on the one hand railing against corrup-tion in public life, are strong opponents of privatisacorrup-tion on the other (for exam-ple, Kristianawati 2005), notwithstanding abundant evidence that state-owned enterprises have always been used to enrich the few at the expense of the general public. Indeed, the new minister for state enterprises has recently gone out of his

TABLE 2 Proposed Revisions to the 2005 Budgeta

Original Revised Change Revised as (Rp trillion) (Rp trillion) (%) % of GDP

TOTAL REVENUE & GRANTS 380.4 443.8 16.7 18.3 Revenue 379.6 438.0 15.4 18.0

Tax revenue 297.8 319.4 7.3 13.1

Domestic taxes 285.5 305.1 6.9 12.6

Income tax 142.2 156.2 9.8 6.4

Oil & gas 13.6 21.3 57.0 0.9

Non-oil & gas 128.6 134.9 4.9 5.6

Value added tax 98.8 98.8 0.0 4.1

Land & building tax 13.5 16.4 21.8 0.7

Excises & other taxes 31.0 33.6 8.6 1.4

International trade taxes 12.4 14.4 16.2 0.6

Non-tax revenue 81.8 118.6 45.0 4.9

Natural resources 50.9 87.7 72.1 3.6

Profit transfers from SOEs 10.6 8.9 –15.8 0.4

Other 20.3 22.0 8.6 0.9

Grants 0.8 5.8 668.2 0.2

EXPENDITURE 397.8 463.3 16.5 19.1

Central government expenditure 266.2 322.4 21.1 13.3

Of whichsubsidies 31.3 60.3 92.8 2.5

Transfers to regions 131.5 140.9 7.1 5.8

Fiscal equalisation funds 124.3 133.7 7.5 5.5

Resource revenue sharing 31.2 40.1 28.5 1.7

General allocation (DAU) 88.8 88.8 0.0 3.7

Special allocation (DAK) 4.3 4.8 10.4 0.2

Special autonomy & adjustment funds 7.2 7.2 0.0 0.3

BUDGET DEFICIT –17.4 –19.5 12.4 –0.8 FINANCING 17.4 19.5 12.4 0.8

Domestic financing 37.6 25.1 –33.2 1.0

Bank 9.0 –3.5 –138.4 –0.1

Non-bank 28.6 28.6 0.0 1.2

Privatisation 3.5 3.5 0.0 0.1

Asset recoveries 4.0 4.0 0.0 0.2

Bond issues (net) 22.1 22.1 0.0 0.9

Secondary mortgage facility –1.0 –1.0 0.0 0.0

Foreign financing –20.2 –5.6 –72.4 –0.2

Foreign borrowing 26.6 29.1 9.4 1.2

Principal repayments –46.8 –34.7 –25.9 –1.4

ASSUMPTIONS Original Proposed Revisionb Accepted Revisionc

Economic growth (%) 5.4 5.5 6.0

Inflation (% p.a.) 5.5 7.0 8.0

Exchange rate (Rp/$) 8,600 8,900 9,300

Oil price ($/barrel) 24 35 45

Interest rate (90-day SBI, % p.a.) 6.5 8.0 8.0

aFigures in the main part of the table are based on the underlying macroeconomic assumptions in the revised

budget proposed to the DPR (GOI 2005a); these assumptions were subsequently revised further (the ‘accepted revision’ figures in the lower part of the table), but the impact of the revisions on the budget had not been disclosed at the time of writing. Percentage changes are based on unrounded figures.

bProposed to the DPR in GOI (2005a). cAgreed with the DPR.

Sources: GOI (2005a); JP, 9/6/2005.

BOX1 THE GREAT(ACADEMIC) DEBATE ON DOMESTIC FUEL PRICES

After months of dithering, the decision to increase the prices of various fuels by an average of 29% was suddenly announced at the end of February, and implemented from the beginning of March (JP, 1/3/2005). While most mainstream economists have been urging adjustments in line with world price movements for many years (and especially with the dramatic increase in world oil prices since late 2003), the decision met with vociferous opposition from the DPR, NGOs and student activists, and more muted concern from the general public. The ensuing debate has been notable for the involvement—on both sides—of the academic economics community.

The president had been taking advice on a wide range of issues from many mem-bers of this community long before his election to office, including from the Institute for Economic and Social Research at the University of Indonesia’s Faculty of Eco-nomics (LPEM–FEUI) and the Faculty of EcoEco-nomics at the Bogor Agricultural Insti-tute (FE–IPB). It appears he had been persuaded that high fuel subsidies were having a ruinous effect on the budget and grossly distorting the pattern of energy consump-tion and trade, while having a highly regressive impact (since individuals’ direct and indirect consumption of fuels is strongly and positively related to their incomes). But he also recognised the political sensitivity of any decision to reduce the subsidy. The LPEM group (and other like-minded economists) therefore recommended that this be explicitly linked with increased expenditures that would benefit the poor, such as on education and health. This package would have an effect similar to that of the Inpres (Presidential Instruction) programs (Ranis and Stewart 1994: 45–8), through which the Soeharto regime used much of the windfall from the OPEC oil booms of the mid- and late 1970s to finance a large expansion in the stock of educational and health facilities, and retail markets, all of which was highly beneficial to the poor.

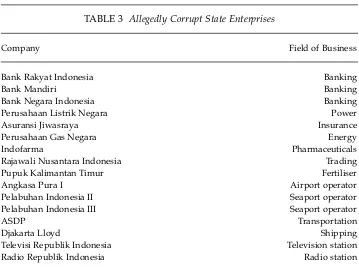

way to turn a strong spotlight on the seemingly never-ending problem of corrup-tion in SOEs, releasing a report listing 16 large state enterprises ‘allegedly riddled with corruption’ (JP, 20/5/2005) (table 3). He followed this up the next day with a statement that this ‘was just the tip of the iceberg as far as corruption in state enterprises went’ (JP, 21/5/2005).

At least some opponents of privatisation are concerned about possible corrup-tion in the divestment process itself: that state enterprises might be sold artifi-cially cheaply to political insiders. But such a stance ignores the virtual certainty that the state enterprises will continue indefinitely to be centres of corruption if they are not divested. Those who profess to be so concerned about corruption would therefore be much better advised to direct their energies to ensuring that transparent, competitive mechanisms for privatisation are established.

Private Sector Provision of Infrastructure Is In, But Privatisation Is Out Given the private sector’s superior ability to operate business enterprises effi-ciently, the new government’s enthusiasm for involving the private sector in infrastructure projects (Soesastro and Atje 2005: 23–6) is commendable. At the

BOX1 THE GREAT(ACADEMIC) DEBATE ON DOMESTIC FUEL PRICES(continued)

While this would have been a perfectly sensible way to blunt political opposi-tion, the LPEM group overplayed its hand, announcing confidently that it had analysed the impact of such a package of policies, and that the level of poverty would decline appreciably (from 16.2% to 13.7%) if it were implemented (Ikhsan 2005). A wide range of outcomes can be generated by such analyses, however— even using similar modelling approaches—depending on the assumptions on which they are based, so the outcomes reported deserve to be considered tentative at best. A group of economists from IPB was quick to point out that the LPEM analysis had not been properly documented, thus precluding the possibility of careful peer review and criticism (see, for example, Sugema 2005). Eventually the IPB group succeeded in prising out enough of the underlying assumptions to be able to raise serious doubts as to their plausibility, and hence the validity of the LPEM findings.

The episode seems to mark an important turning point. For decades, economists linked to LPEM have played a virtually unchallenged role in formulating economic policy. The nature of the New Order regime was such that this group felt little need to defend its arguments before the general public. Provided Soeharto himself could be convinced, its policy recommendations were almost invariably implemented. However, with the new president having gained his PhD in economics from IPB shortly before being elected, it is perhaps no surprise that LPEM’s stranglehold on providing economic policy advice to the government has been broken. It is clear that the president and his ministers are now calling on a wide range of academic and pri-vate sector economists, directly or indirectly, to contribute their views on policy issues.

same time, it is noteworthy that all momentum has been lost from the privatisa-tion process. Despite drawing attenprivatisa-tion to the enormous problem of corrupprivatisa-tion in the SOEs, the state enterprises minister seems to be pinning his hopes on wholesale replacement of some 1,500 commissioners and directors of these firms to bring about honest and competent management (Gatra, 7/5/2005). The alter-native conclusion is that the corruption problem is inherent in state ownership in Indonesia, and that the solution is in fact to be found in full privatisation.

This loss of momentum suggests that the government lacks a consistent con-ceptual framework for delineating the appropriate scope of its own economic activity, given that the economic rationales for both privatisation and private sec-tor involvement in infrastructure provision—namely, the greater efficiency that comes with private ownership and risk-bearing—are identical. In the National Medium-Term Development Plan 2004–09 (GOI 2005b), the discussion of state-owned enterprises extends to a mere three pages, and contains no mention what-soever of privatisation, while the chapter on infrastructure—the government’s new fad—extends to no less than 110 pages. There have been no recent privatisa-tions of any note, and none was on the drawing board at the time of writing.

TABLE 3 Allegedly Corrupt State Enterprises

Company Field of Business

Bank Rakyat Indonesia Banking

Bank Mandiri Banking

Bank Negara Indonesia Banking

Perusahaan Listrik Negara Power

Asuransi Jiwasraya Insurance

Perusahaan Gas Negara Energy

Indofarma Pharmaceuticals

Rajawali Nusantara Indonesia Trading

Pupuk Kalimantan Timur Fertiliser

Angkasa Pura I Airport operator

Pelabuhan Indonesia II Seaport operator

Pelabuhan Indonesia III Seaport operator

ASDP Transportation

Djakarta Lloyd Shipping

Televisi Republik Indonesia Television station

Radio Republik Indonesia Radio station

Source: Office of the Minister for State-owned Enterprises, cited in JP, 20/5/2005.

Indeed, the minister has argued that many SOEs are ‘not ready’ for privatisation, and has proposed that it is unnecessary in any case, since he expects to be able to ensure a significantly higher than budgeted flow of dividends from the state enterprises (Kompas, 10/6/2005). Elsewhere he is reported as saying he prefers not to sell more shares in state companies, but rather to buy back those in strate-gically important firms (AFX News Limited, 13/6/2005); broadly similar senti-ments were also expressed by the vice president (Reuters, 10/6/2005). The coordinating minister for economic affairs responded by insisting that the privati-sation revenue target of Rp 3.5 trillion for 2005 be met, but even this was hedged with the hint that ‘we won’t sell if the price is not high enough’ (JP, 14/6/2005); there was no mention of which firms were to be privatised.

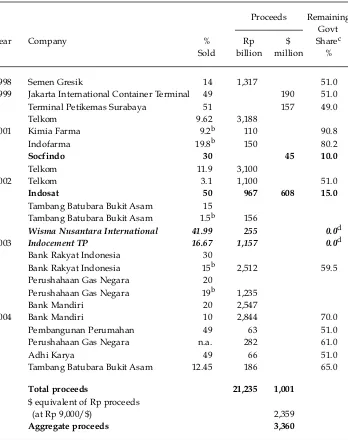

This lack of enthusiasm for privatisation is widespread, which largely explains why the results achieved hitherto are virtually negligible. Almost all of the small number of ‘privatisations’ undertaken have been partial, involving the divest-ment of a minority share in the enterprises in question. There is little point in doing this. The economic argument in favour of privatisation depends crucially on the private sector both gaining management control and taking on the risk of losses, but this has not been the case in most of the ‘privatisations’ witnessed dur-ing the last several years (table 4). Of course, some cash has been raised in this manner, but since the government is able to borrow in both the domestic and international markets, this achievement is of little consequence.

Successive governments’ failure to accomplish much by way of genuine pri-vatisation suggests clearly that involving the private sector in the provision of

TABLE 4 Progress with Privatisation, 1998 – June 2005a

Proceeds Remaining Govt

Year Company % Rp $ Sharec

Sold billion million %

1998 Semen Gresik 14 1,317 51.0

1999 Jakarta International Container Terminal 49 190 51.0

Terminal Petikemas Surabaya 51 157 49.0

Telkom 9.62 3,188

2001 Kimia Farma 9.2b 110 90.8

Indofarma 19.8b 150 80.2

Socfindo 30 45 10.0

Telkom 11.9 3,100

2002 Telkom 3.1 1,100 51.0

Indosat 50 967 608 15.0

Tambang Batubara Bukit Asam 15

Tambang Batubara Bukit Asam 1.5b 156

Wisma Nusantara International 41.99 255 0.0d

2003 Indocement TP 16.67 1,157 0.0d

Bank Rakyat Indonesia 30

Bank Rakyat Indonesia 15b 2,512 59.5

Perushahaan Gas Negara 20

Perushahaan Gas Negara 19b 1,235

Bank Mandiri 20 2,547

2004 Bank Mandiri 10 2,844 70.0

Pembangunan Perumahan 49 63 51.0

Perushahaan Gas Negara n.a. 282 61.0

Adhi Karya 49 66 51.0

Tambang Batubara Bukit Asam 12.45 186 65.0

Total proceeds 21,235 1,001

$ equivalent of Rp proceeds

(at Rp 9,000/$) 2,359

Aggregate proceeds 3,360

aCases of 100% divestment are shown in bold italics; divestments to small shareholdings

(10–15%) are shown in bold.

bIssue of new shares (as distinct from sale of existing shares).

cAs at June 2005. Blank cells indicate later divestment(s) that further reduced the

govern-ment’s share.

dThe companies Wisma Nusantra International and Indocement were both formerly

pri-vate companies in which the government had acquired shares as a result of financial dif-ficulties they experienced.

Source: Department of State-owned Enterprises, personal communication.

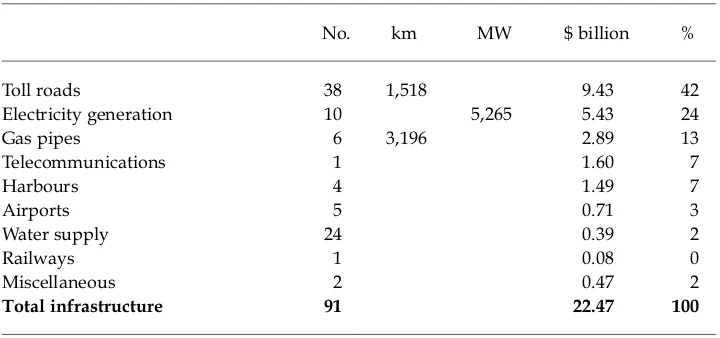

TABLE 5 Infrastructure Summit Projects by Category

No. km MW $ billion %

Toll roads 38 1,518 9.43 42

Electricity generation 10 5,265 5.43 24

Gas pipes 6 3,196 2.89 13

Telecommunications 1 1.60 7

Harbours 4 1.49 7

Airports 5 0.71 3

Water supply 24 0.39 2

Railways 1 0.08 0

Miscellaneous 2 0.47 2

Total infrastructure 91 22.47 100

Source: Individual projects are listed at <www.iisummit2005.com/projects.html>. infrastructure is also likely to be fraught with difficulty. The problem is not that the private sector does not want to be involved. On the contrary, it is interested in any economic activity in which there is an acceptable balance between expected profit and risk. Rather, the problem is that there are strong interests within the bureaucracy, in government-owned enterprises and in the political parties whose actions will work in one way or another to frustrate this worthy objective: the government’s failure at the infrastructure summit in January 2005 to produce more than one of the 14 regulations said to be necessary to provide a sound legal basis for private sector participation in infrastructure (Soesastro and Atje 2005: 25) should be interpreted in this light. Nor is it really surprising that there is as yet relatively little to show by way of concrete follow-up to the summit.

Obstacles to Private Sector Involvement in Infrastructure

Soesastro and Atje (2005: 25–6) introduced their discussion of the government’s infrastructure summit in January 2005 with background from a section of a World Bank report on Indonesia’s ‘infrastructure challenges’ (World Bank 2005). Two points from this report are of especial interest. First, one of the most obvious defi-ciencies in Indonesian infrastructure is the inadequacy of flood mitigation and stormwater drainage systems; flooding, and the resulting property damage, injuries and deaths, are a commonplace in the rainy season. Yet this item was absent from both the Bank’s list of ‘infrastructure challenges’ (World Bank 2005: table 3.4) and the infrastructure summit list of projects on offer to the private sec-tor (table 5). In the latter case this presumably reflects the fact that protection against flood damage is a localised public good (i.e. one for which it is impossible to charge ‘consumers’ a price, since they cannot be excluded from its benefits); this precludes private sector involvement (except in the design and construction phases). It is hard to explain the absence of this item from the Bank’s list, however. Second, the Bank’s explanation of the causes of infrastructure deficiencies (the late 1990s crisis, poor institutional and regulatory frameworks, corruption and

5One justification for halting the projects was to cut the demand for imports in view of the

sudden emergence of high capital outflow, but the impact on the current account would have been far too slow relative to the rapid change in the capital account for this to be effective. The better way to deal with the sudden capital account deterioration would have been to allow the exchange rate to adjust to the new circumstances. In reality, it is arguable that there was also a political explanation for stopping the projects: namely, to try to force Soeharto to curtail the rapacity of his family members and their business cronies.

6The Bank is not unaware of the importance of proper pricing—noting, for example, that

‘low tariffs discourage local water companies from expansion and adequate maintenance’ (World Bank 2005: 46). But the minimal degree of emphasis given to this issue in its report belies its crucial importance.

decentralisation) left a great deal unsaid. There was no mention of the fact, now of mainly historical interest, that a large number of private sector infrastructure projects—toll roads and electricity generation plants in particular—had been shelved at the outset of the crisis. There was every reason for the government to renegotiate the contractual terms of these projects, all of which were sponsored by the presidential first family and its cronies. But the damage done by halting them altogether (apart from the perversely negative impact on aggregate demand at precisely the time the private sector was cutting back its own spending) is now becoming increasingly obvious: these are the very kinds of projects the govern-ment is now trying so hard to promote, in an attempt to catch up on more than seven years of lost progress.5Toll roads and power projects account for more than

half the total number of projects on the summit list, and almost two-thirds by value.

More relevant in the current context is the Bank’s lack of emphasis on the more fundamental explanation for infrastructure deficiencies that were apparent even before the crisis: namely, government pricing policies in relation to infrastructure services. For years most roads have been made available free to users, while water, electricity, telephone lines and train services have been supplied at prices far below unit costs. The obvious consequence of this is that the government departments and state enterprises in question made losses and therefore had to rely on the budget for their survival. Thus the reason the government has failed so clearly to maintain an adequate level of spending on infrastructure is precisely that the more it provided, the greater the budgetary burden it would have to carry.6 This explanation is even more relevant in the case of flood mitigation

infrastructure, which generates no revenues at all to offset its costs.

Instead of utilising the price mechanism to ensure that such services are sup-plied up to the level at which users are willing to cover the costs, the government supplies them only to a level determined by the political process of allocating available fiscal resources. Non-price rationing is then needed to keep supply and demand in balance. People are kept off the streets and roads by high congestion costs; they are kept off the trains by overcrowding, poor service and other kinds of discomfort; electricity consumption is kept down by blackouts; and the demand for telephone lines is kept in check by long waiting lists. In short, the fundamental explanation for infrastructure deficiencies is the policy of providing infrastructure services at well below cost.

The projects offered to the private sector at the infrastructure summit all seem to have in common that it would be feasible to undertake them for profit, at least

at first glance. This is straightforward in the case of a natural gas pipeline. All that is needed is a long-term contract between the pipeline operator and either the buyer or the supplier of the gas (although the government would need to facili-tate the acquisition of land on which to lay the pipeline). But in other cases it is not at all straightforward. Consider the supply of drinking water, for example. Government-owned water supply companies in Indonesia have probably never charged users the full cost of supplying them with drinking water, and certainly do not do so at present, but if the private sector is to take over the supply func-tion, prices will need to be increased significantly.

Quite simply, the private sector will not be interested in providing these kinds of infrastructure services unless it can be confident that its revenues will exceed its costs (including the cost of capital) by a margin sufficient to justify the risks involved. If the government wants to get the private sector involved in the infra-structure business, it will need to give serious consideration to application of the crucially important ‘user pays’ principle. And, given the obvious political diffi-culties the government faces every time it wishes to raise prices under its control, it seems likely that the private sector would require the government to raise tar-iffs to a profitable level before it contemplated becoming involved.

Eminent Domain

One of the obstacles to the provision of infrastructure in Indonesia has been the absence of the legal concept of ‘eminent domain’: that is, the power of the state to appropriate property for public use. Until very recently, the land needed to con-struct a road, for example, had to be purchased at a price acceptable to its own-ers. Many such owners understood that this put them in a strong bargaining position, given that the government had no real choice over which land it needed to purchase. The opportunity cost of not being able to complete a road because of failure to purchase the last of the required pieces of land is approximately the value of the road to its intended users, so there is good reason to hold out for a price far higher than that of other land located nearby (Witular 2005b). The desire to preclude such behaviour provides the rationale for eminent domain, which is now to be embraced by Indonesia following the introduction in May of Presiden-tial Regulation 36/2005 (GOI 2005c). The regulation provides that land may be compulsorily acquired by governments for a variety of development purposes if an acceptable price cannot be agreed upon by negotiation.

Given the abundance of cases of streets, roads and toll roads whose completion or proper functioning has been kept on hold for months, if not years, by land owners holding out for higher compensation, it seems surprising that most com-ment on this new regulation has been negative. This response is attributable to the widespread distrust of governments in Indonesia, and the consequent fear that the regulation may be misused to acquire land cheaply for the benefit of politically powerful interests (JP, 6/6/2005). Such concerns are not without foun-dation. Indeed, the apparent abuse of eminent domain has become a political issue of some importance in the US, for example (Greenhut 2004). The new regu-lation tries to allay these concerns by requiring independent teams to determine fair amounts of compensation, but opposition to it might have been less if the list of ‘developments in the public interest’ for the compulsory resumption of pri-vately owned land had been greatly shortened (table 6). In the case of many of

these public purposes, the government would have considerable choice as to suit-able sites, so there is no obvious reason for giving it the power of compulsory acquisition.

INFRASTRUCTURE FROM A REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE: WEST JAVA AND BANDUNG

For the purposes of this Survey, the author made a brief visit to Bandung, the cap-ital of West Java province, to obtain a regional perspective on infrastructure prob-lems and issues. Information and data were obtained from officials of the provincial and municipal planning agencies and the roads authority (Dinas Bina

TABLE 6 Types of Development Encompassed by Eminent Domaina

Application of eminent domain seems reasonable(little choice as to location) Roads, toll roads, railways, clean water pipes and sewers

Dams, irrigation canals and other irrigation installations Electricity generation, transmission and distribution facilities Ports, airports, railway stations and bus terminals

Nature and cultural reserves Parks

Garbage disposal sites

Application of eminent domain seems unnecessary(choice exists as to location) Hospitals and health clinics

Prisons Cemeteries Sporting facilitiesb

Post and telecommunications facilities

Radio and television broadcasting stations and supporting facilities Places of worship

Schools and educational facilities Social institutions

Offices of government and diplomatic missions Facilities of the armed forces and the police Low cost housing complexes

Marketsc

Public safety facilitiesd

aInfrastructure types from the government’s list of developments in the public interest have

been classified based on the author’s judgment as to whether the government would have choice as to location. In such cases land owners would not have a monopoly position, so resort to eminent domain seems unnecessary.

bPresumably this encompasses golf courses. The owners of many existing courses have

been accused of taking over extensive tracts of land by threat or force without paying rea-sonable compensation, which is exactly the concern of opponents of the new regulation.

cProbably of little practical importance with the rapid spread of modern retailing.

dNot clear what types of facilities this includes.

Source: Adapted from GOI (2005c).

7Earlier in 2005 a number of textile factories in the Bandung area became bankrupt and

were forced to close as a result of flooding, which is said to be becoming increasingly severe over time. Other factory owners suffered serious financial losses.

Marga), and from spatial planning experts at the Bandung Institute of Technol-ogy. The problems faced by different provinces all vary somewhat, of course, but there is much in common as well, so this provincial case study should be of broader interest Indonesia-wide.

The general picture of infrastructure deficiencies in West Java and its capital mirror those reported by the World Bank for Indonesia as a whole (Soesastro and Atje 2005: table 6). Road and rail networks, ports, airports and other passenger and freight terminals are all inadequate relative to the demand for the services they provide. Irrigation systems are in a state of disrepair. Relatively few house-holds have connections to clean water supply, sewerage, electricity and telecom-munications. Rivers and drainage systems are polluted by household and industrial waste. Flooding of villages and urban areas in the rainy season is com-monplace and causes enormous material damage, not to mention injury and loss of life.7

Both the province and city planning agencies have quite detailed term plans for overcoming these deficiencies. Unfortunately, like the medium-term plans prepared by their central government counterpart (Bappenas, the national planning agency) (Booth 2005), these ‘plans’ are best considered as mere wish-lists of improvements the agencies hope to see. They lack adequate expla-nations for present infrastructure deficiencies, without which it is impossible to say anything useful about how these should be overcome.

The Grand Plan for West Java

Following the lead of the central government, the provincial government was planning to host its own infrastructure summit in August 2005, at which it intended to offer some 50 infrastructure projects worth $16 billion, encompass-ing toll roads, power supply, airports, seaports, water supply and waste man-agement (Hakim 2005). The planning vision is focused on the intensive development of three main urban areas (Pusat Kegiatan Nasional, National Cen-tres of Activity) in the northern and central parts of the province: the Bogor–Depok–Bekasi conurbation (in the Jakarta hinterland); Bandung itself (located in the geographic centre of West Java, following the recent ‘secession’ of the western portion of the province to become the new province of Banten); and the port city of Cirebon (on the north coast, near to Central Java). Beyond this it recognises a further six Regional Centres of Activity (Pusat Kegiatan Wilayah). Four of these (Cianjur–Sukabumi, Cikampek–Cikopo, Tasikmalaya and Kadi-paten) are located along major transport corridors connecting Bandung to the outside world, while the other two (Pangandaran and Pelabuhanratu) are on the less densely populated and less developed south coast in the east and west cor-ners, respectively, of the province.

The broad plan relies heavily on the creation and upgrading of infrastructure: the construction of toll roads connecting these centres (but excluding Pangan-daran and Pelabuhanratu), plus extension of the Java–Bali high voltage electric-ity transmission network to those centres away from the northern side of the

8The former connect provincial capitals with each other; the latter connect provincial

cap-itals with district capcap-itals and municipalities.

9A large new dam is planned at Jatigede, but this plan has been on the books for many

years without coming to fruition, apparently because of the unwillingness of the central government to fund it.

province. Upgrading of the railway system, the ports at Cirebon and Pelabuhan-ratu, and the airports at Bandung and Nusawiru (in the southeast corner of the province) are also on the agenda, not to mention construction of a new inter-national airport between Bandung and Cirebon, and a domestic airport at Pelabuhanratu.

Although this vision is impressive in its scope, most of these infrastructure developments appear to be outside the control of the government of West Java, since they are the responsibility of companies owned by the central government. The major toll roads are the responsibility of PT Jasa Marga; the railways of PT Kereta Api; electricity transmission of PT PLN; the ports of PT Pelindo I and II; and the airports of PT Angkasa Pura II. Thus it would appear that what actually happens in relation to major infrastructure development will depend mainly on decisions made at the centre rather than in the province. It will be interesting to see how this issue is resolved at the forthcoming West Java infrastructure summit. Within the much narrower scope of road and irrigation infrastructure, and at a more modest level, the regional government certainly has an important role to play, however, and it seems clear that it has fallen behind in this. Central govern-ment regulations define the parts of the road and irrigation networks that are its own responsibility, and the parts that are the responsibility of the province and the districts, respectively. Of some 22,507 km of roads in West Java, the provincial government is responsible for just 2,141 km ‘collector I’ and ‘collector II’ roads.8

Only 87.5% of these are classified as being in good (baik) or fair (sedang) condition. Similarly, of about 1 million ha of irrigated land (sawah) in West Java, the provincial government is responsible for only about 74,000 ha. No less than 31% of the irrigation structures for which the province has responsibility are classified as damaged (rusak), and a further 18% as severely damaged (rusak berat). Irriga-tion channels are in even worse shape, with 31% damaged and 43% severely dam-aged. As a consequence of inadequate repair and maintenance programs, and of inadequate capacity of the dams that feed the irrigation systems, continuous sup-ply of water cannot be maintained to all areas, especially in the dry season.9Thus

the average intensity of cropping on irrigated land is only 185%, compared with the target of 200% (which could be achieved under double cropping).

There are 55 garbage dumps throughout the province, but only 28 of these use the sanitary landfill system (which involves compression of garbage prior to cov-ering it with compacted soil); the remainder are uncompacted open dumps. Aside from the problem of pollution associated with the latter, there is the more immediate danger of their collapse in the rainy season as their height increases. In February, an open dump at Leuwigajah, near Bandung, collapsed, burying adjacent settlements under vast amounts of garbage, with the loss of more than 130 lives (Pikiran Rakyat, 22/2/2005; UPC 2005). The management of sewage also leaves much to be desired, with only 11 of a total of 17 sewage treatment plants operational.

10So much so that part of the new road collapsed shortly after it was opened to traffic. 11Implausible though it may seem, Bappeda Bandung (2004: 16) reports that only about

70% of the city streets actually possess drainage channels: ‘Overall, the drainage system in Bandung is still not well planned.’

12In a city with a population of 2.8 million in 2004, the number of piped water connections

was just 143,250, according to the Bandung municipal water supply company (PDAM Kota Bandung).

13Only about 20% of the population of Bandung municipality live in houses connected to

the sewerage network. Even so, there is only a single treatment plant, and it can only han-dle sewage produced by about 15% of the population. A considerable quantity of raw sewage therefore flows directly into the local river system (Bappeda Bandung 2004: 16).

14These performance shortcomings are discussed in detail in Bappeda Bandung (2004:

chapter 2).

15The population growth rate was around 3.8% p.a. during the 1990s, and the current city

development plan envisages growth at 2.5% p.a. in the decade to 2013. Infrastructure Problems in Bandung

The demands for infrastructure increase with population density and average incomes, so, with the exception of irrigation and inter-city transport systems, infrastructure is mainly an urban issue. Accordingly, we turn now to consider the case of the capital of West Java. Several of the main thoroughfares of the city of Bandung were in sparkling condition at the time of the writer’s visit. A good deal of sprucing up had taken place in preparation for the 50th anniversary of the Asia–Africa Conference held in Bandung in April 1955 (Mackie 2005), and a new toll road linking the city to Jakarta had been rushed to completion10to allow

vis-iting foreign dignitaries to be driven to Bandung and back with minimum delay. But the realities of infrastructure shortcomings are obvious to the residents.

The city streets are not able to accommodate the rapidly growing numbers of cars, motorcycles, buses and trucks that use them. Lack of capacity to collect and properly dispose of garbage results in large amounts of it being thrown into cul-verts, canals and rivers, reducing their ability to cope with heavy rainwater run-off. Overloading of the drainage system and blockage of street drain inlets by garbage mean that heavy rainstorms quickly turn streets to streams, resulting in the frequent inundation of low-lying areas.11Flooding causes streets and roads to

deteriorate rapidly, further reducing their traffic-carrying capacity. Because of the limited coverage of the clean water supply network, countless families have to rely on groundwater, which is increasingly polluted and unhygienic as a conse-quence of the similarly limited coverage of the sewerage system.12,13And even

those fortunate enough to have a water connection cannot be sure of a continu-ous supply throughout the day, as demand often exceeds the available supply.14

Performance, Policing and Pricing

Explanations for these shortcomings of infrastructure performance usually tend to focus on the rapid spread of vehicle ownership, the limited financial resources of municipal governments, the failure of the public to use existing infrastructure properly, the lack of public concern for the environment, and the rapid build-up of the urban population due to migration from rural areas.15But these

16Attempts to do so may meet with violent resistance: see, for example, Harsanto (2005).

tions are unsatisfactory from the viewpoint of economic analysis, and provide lit-tle useful input to the search for policy solutions. In fact, most if not all the expla-nation for poor infrastructure performance can be found in inadequate policing and inappropriate pricing.

‘Inadequate policing’ is shorthand for failure of the relevant authorities to enforce laws and regulations in relation to land use, widely interpreted to include road use. First, there is a lack of control over the conversion of forests and farm land to residential, commercial and industrial use, in contravention of land zon-ing stipulations (Hardjono 2005: 217–22). One consequence is much more rapid run-off of rainwater to the drainage system; a second is erosion and siltation of watercourses: both contribute to flooding. Second, there is a lack of control over petty traders and food stall owners, who carry on their business activities on foot-paths and on street surfaces, attracting large numbers of pedestrians and thus preventing the smooth flow of vehicular traffic. Third, there is excessive reliance on on-street parking, which also cuts the vehicle-carrying capacity of roads. Fourth, there are no roadside slots to accommodate buses while they load passen-gers, and there is little attempt to prevent them from blocking traffic while they wait for more customers. Finally, there is no effective enforcement of load limits for trucks, which results in rapid deterioration of road surfaces forced to carry far heavier loads than those for which they were designed.

The city planning agency is well aware of the problems of improper land use, but appears to have little by way of concrete proposals to overcome them. Chap-ter 6 of Bappeda Bandung (2004) is devoted to the topic ‘Control of Land Use’, but comprises just three pages of text in which it emphasises the need to tighten up on enforcement of the regulations on land use. The legal basis exists for action against entities that use land in contravention of permits that have been issued; what appears to be lacking is the political will to make use of it. On the one hand, wealthy people who wish to construct houses or other buildings on land zoned as open green space (ruang terbuka hijau) presumably bribe the relevant officials to look the other way. On the other, there is a reluctance to act against relatively poor individuals who commandeer space on streets and footpaths to eke out a living.16

The second fundamental explanation for the inadequacy of infrastructure in Bandung (and, presumably, in other cities and towns in Indonesia) is the failure to price infrastructure services rationally. If the provision of infrastructure were in the hands of private sector firms there would be no question of lack of funds for its expansion. Driven by the profit motive, such firms could be expected to create new infrastructure wherever there was an effective demand for it—in other words, wherever the willingness to pay for infrastructure services was strong enough to cover the cost of their provision, including a reasonable level of profit. By contrast, the government-owned firms and agencies actually responsible for Bandung’s infrastructure are reluctant to engage in expansion because policies that set prices well below costs render expansion unprofitable, or unable to be covered by available budgetary subventions.

Thus, although politically difficult, the solution to the ‘lack of finance’ problem is technically simple. For example, the water supply company (PDAM) would

have no trouble obtaining the funds needed to expand vastly its provision of clean water and sewage disposal services if it were merely to increase its connec-tion fees and water supply tariffs. Likewise, the city would be able to pay for the maintenance and improvement of streets, footpaths and their associated drainage systems, and for a proper garbage disposal system, if it could impose rates and taxes on land and buildings sufficient to cover the costs of these activities. Unfor-tunately this is precluded by the current fiscal decentralisation arrangements, under which the central government’s finance ministry retains control of these kinds of taxes. Significant improvement in infrastructure in urban areas through-out Indonesia—one of the main potential benefits of decentralisation—is unlikely to occur under these arrangements.

The failure of city governments to charge residents the full cost of all the serv-ices they enjoy condemns urban infrastructure to permanent inadequacy, since the political process will never generate tax revenue sufficient to finance the demand for infrastructure services at artificially low prices. Moreover, govern-ments’ failure to enforce sensible land use regulations amplifies the problem by allowing individuals and firms to impose negative externalities on others, which are manifested in a general degradation of the urban environment. It is hardly surprising that many individuals turn their backs on the harsh realities of village life when, for example, they can earn higher incomes carrying on subsidised com-mercial activities by virtue of being permitted to ‘set up shop’ on streets and foot-paths for which they pay no rent. Nor is it surprising that more wealthy individuals seize the opportunity presented by a corrupt bureaucracy to under-take developments of various kinds on land that should not be used for such pur-poses. In both cases the demands on infrastructure become greater; but the financial wherewithal to meet these demands is absent, so infrastructure becomes increasingly deficient. In turn, cities that are dysfunctional because of poor infra-structure create a drag on the performance of the entire economy.

CIVIL SERVICE REFORM Anti-corruption Drive

The new government’s reform efforts to date have focused almost entirely on the objective of detecting and punishing corruption. Another anti-corruption agency, the Coordinating Team for Eliminating Corruption (TK Tipikor), comprising some 51 prosecutors, police officials and state auditors and led by the deputy attorney general, was added to the government’s arsenal in May, by way of Pres-idential Decree 11/2005 (JP, 6/5/2005). The need for the new body may be doubted, given the existence of the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), the Anti-Money Laundering Centre, the National Ombudsman and the Supreme Audit Agency (BPK) (Baskoro et al. 2005), but it has moved quickly to show that it means business.

The anti-corruption drive has been getting plenty of attention. For example, the wealthy and powerful former governor of Aceh province has been sentenced to 10 years in prison (although for some time this translated in reality to ‘city arrest’ [Laksamana.Net, 22 April 2005]), while a number of top executives of the state-owned Bank Mandiri and senior officials of the election commission were arrested on charges of corruption in May (JP, 18/5/2005, 21/5/2005). More

17For some case studies of a new CEO acting to reform business enterprises in the

Indo-nesian context, see Djohan (no date).

18One explanation for having such a large team may be the desire to control cronyism in

high-level appointments.

recently the president director of the state banknote printing company, PT Peruri, and two of his subordinates have been declared suspects in a large embezzlement case at the company (JP, 6/6/2005).

Throwing a few ‘big fish’ in prison may be salutary, and may bring some imme-diate sense of gratification, but civil service reform needs to be conceptualised far more widely than merely the attempt to punish corrupt officials. The bureaucracy wastes its resources on things it does not need to do; it smothers the private sector in red tape; it has too many employees filling certain types of positions and too few in others; and its employees’ skills are not well matched to the work they do, such that the things it needs to do are not done well. The fundamental aim, there-fore, must be to improve the productivity of civil servants, and thus their organi-sations, over time. Among other things, this will require greatly improved systems of performance appraisal, linked to the promotion mechanism; detecting and penalising corrupt behaviour should be just one aspect of this.

The New Broom Has Been Slow to Sweep Clean

It is perhaps in this area that the performance of the new regime has been most disappointing. The election of a new president in a country whose economy has been floundering is—or should be—analogous to the appointment of a new CEO to revitalise a large business conglomerate that has fallen on hard times.17 The

first step is to take stock of the existing top management, keeping those thought competent and willing to implement vigorously the vision of the new ‘number one’, and promoting or recruiting new blood to replace those not meeting these criteria; this corresponds to appointment of a new cabinet. The second is to repeat this process at the next lower level in the hierarchy, and so on down through the organisation.

The first indication that election campaign reform promises might not be ful-filled became evident when the incoming president could only finalise the compo-sition of his cabinet at the last minute, filling some of the most important posts on the basis of political, rather than competence, considerations (Soesastro and Atje 2005: 6). Perhaps more importantly, reform has been held back subsequently because ministers have been prevented from appointing the best available people to top (echelon I) positions (mainly directors, secretaries and inspectors general) in their departments. Such appointments require the assent not only of the president, but also of the other members of the Tim Penilai Akhir (Final Evaluation Team), which includes the State Secretary, Minister for Home Affairs, Minister for Empowerment of the State Apparatus, and chief of the State Intelligence Agency.18

But the team meets infrequently, so it has been difficult for ministers to get their preferred top officials in place. The trade minister, Mari Pangestu, was the first to get her list of new echelon I appointments approved, but not until fully five months after the SBY government took office (JP, 30/3/2005). Other ministries have had to wait considerably longer: for example, new echelon I appointments in

19A hopeful sign is the recent announcement that the government is looking to revise

Law 43/1999 on public servants in order to be able to speed up the process of discharging the industry and education departments did not occur until two months later (Kompas,20/5/2005; JP, 20/5/2005).

Rigid Rules on Recruitment and Promotion

Delays in making these top-level appointments are not the only reason reform has been slow. Also important is the nature of the rules that govern the civil service, particularly in relation to recruitment and promotion. Broadly speaking, recruit-ment is restricted to new school and university graduates, which means that important managerial positions and those requiring particular professional skills can be filled only from within the department in question (or, with some difficulty, from other areas in the wider civil service), whether or not well suited personnel are available. The new trade minister found only two overseas-trained economics PhDs within her entire ministry, making her heavily reliant on the outside aca-demic community and foreign aid agencies for research and policy analysis. And even if young officers demonstrate outstanding competence, it is almost impossi-ble to appoint them to high-level positions, because they are not sufficiently sen-ior for such promotions to be permitted within the existing regulations.

To get around these problems, the new state enterprises minister, Sugiharto— an apparently wealthy individual coming from a big business background— quickly brought in some seven high-level advisers from the private sector, apparently without being able to appoint them formally as civil servants (Wiranto et al.2005). Assuming these individuals are not working pro bono, the implication is that some outside source of funds needs to be tapped in order to pay their salaries, an option not open to ministers lacking considerable private resources or close connections with the business community. The coordinating minister for economic affairs, who also comes from a big business background, appears to be following a similar strategy.

Remuneration and Promotion

The performance of the bureaucracy depends also on its systems of remuneration and promotion. Here, again, the present reality leaves a great deal to be desired, and would be considered risible by anyone familiar with these aspects of person-nel management in the private sector context. Frequent complaints that the civil service is poorly remunerated appear to lack foundation, however (Filmer and Lindauer 2001). On the contrary, the competition for government jobs is so intense that the payment of bribes in order to secure positions and promotions in the bureaucracy is a commonplace (ADB 2004: 62). This cannot be explained by the level of basic salaries, since these fall increasingly far below comparable pri-vate sector salaries as officers move up through the hierarchy. Rather, systems have evolved over several decades within which the pretence of a relatively egal-itarian salary structure can be maintained, with sufficient incentive still provided to officials not to abandon their positions.

The main components of these systems are the provision of tenure (under which it is exceedingly difficult to dismiss civil servants, even if guilty of corrup-tion),19 in combination with the guarantee of a state pension upon retirement;

officials found guilty of corruption (Witular 2005a). Getting rid of individuals for poor per-formance is virtually impossible, however. The best that can be done is to deprive them of their structural positions, leaving them employed but without any function and without any subordinates. This results in the loss of entitlements to the various allowances that went with the previous position.

valuable fringe benefits, including coverage of medical expenses of employees and their immediate families, and transport to and from the office, extending to cars and housing for high-level officials; the payment of various allowances to the holders of managerial or functional positions for which particular professional skills are required; the appointment of top officials to boards of commissioners of state enterprises, where they earn additional large salaries; the practice of mak-ing ad hocpayments to officials who serve on a bewildering variety of committees (often involved with procurement), or attend meetings, conferences, workshops and so on; and the implicit promise of additional income from direct or indirect participation in corruption and bureaucratic extortion (ADB 2004: 58–9, 63, 66–7). The dividing line between these last two components of extra income is very blurred. The ad hocpayments just mentioned need to be funded, and it is very often the case that this is accomplished via slush funds (‘dana taktis’, or ‘tactical funds’, in the new vernacular) that are typically accumulated from ‘gratuities’ paid by suppliers to government agencies. The election commission corruption scandal mentioned earlier relates to the disposition of money from a slush fund to which the suppliers of ink, paper, ballot boxes and so on contributed, but this practice of taking kickbacks from contractors is regarded by most as nothing out of the ordinary (Bayuni 2005). Likewise, funds left over from the government-controlled Haj pilgrimage program have been found to have been ‘used for five kinds of activities, including providing welfare for (ministry) employees’ (Sukar-sono 2005).

The existence of such systems explains the plentiful supply of applicants for jobs in the civil service (and, for that matter, the military, the police and the state-owned enterprises). It also gives the lie to the often heard claim that civil servants are forced into corruption by low salaries: on the contrary, jobs and promotions are bought and sold precisely for the opportunities they present for generating income illegally (although, of course, not by all) (ADB 2004: 62). In such a system, promotions tend to go to the highest bidders—the individuals willing and able to exploit these opportunities most energetically—not those whose performance is superior to that of their peers, as would be the case if civil servants had to com-pete for promotions on a level playing field on the basis of demonstrated capac-ity to perform.

The numerous deficiencies of public administration in Indonesia are discussed in far greater depth than is possible here in ADB (2004: chapter V). Suffice it to say that significant improvement in the performance of the bureaucracy will require radical bureaucratic reforms, such as opening up the civil service at all levels to recruitment from outside; combining the full diverse array of payments and entitlements that now comprise civil servants’ total remuneration into a much simpler, transparent pay structure, with minimum reliance on special entitle-ments and ad hocpayments; introducing transparent and fair performance assess-ment procedures to serve as the basis for decisions on promotion; and returning