Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Can School Oversight Adequately Assess

Department Outcomes? A Study of Marketing

Curriculum Content

Stephen T. Barnett , Paul E. Dascher & Carolyn Y. Nicholson

To cite this article: Stephen T. Barnett , Paul E. Dascher & Carolyn Y. Nicholson (2004) Can School Oversight Adequately Assess Department Outcomes? A Study of Marketing Curriculum Content, Journal of Education for Business, 79:3, 157-162, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.79.3.157-162 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.79.3.157-162

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 16

View related articles

he environment for business edu-cation challenges institutions and their academic departments in many ways. Educators must develop and offer curricula that are effective and efficient, identify experiences relevant to current and future professional needs, and build academic programs that demonstrate value and continuous improvement. Feedback is a vital part of any continu-ous improvement program. Although the purpose and importance of out-comes assessment is clear, how to design and implement such programs is complex and confusing, as evidenced by reports that most schools lack compre-hensive outcomes assessment programs (Kimmell, Marquette, & Olsen, 1998).

Curricular content is a critical ingre-dient in an academic or professional educational program. Moreover, the process of ongoing curriculum improve-ment requires that educators regularly assess the outcomes of their particular programs. A key step in defining and measuring curricula is establishing clear mission-driven criteria for individual programs. AACSB International, The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, provides one source for these criteria. Administrators and educators often use these criteria as guidelines in defining the mission for institutions and programs. Because the course requirements for various

busi-ness majors and programs are unique by discipline yet also constitute much of a student’s curriculum, we wondered if it is effective to base outcomes assessment on the broader college mission-driven criteria. Our premise is that such broad, strategic, college-level criteria do not provide enough direction at the tactical departmental level at which educators implement the courses that deliver cur-ricular content.

Our purpose in this study was to explore the perceptions of a group of leaders in one discipline regarding the use of college-wide curricular standards as criteria in assessing outcomes in a department. Because AACSB standards

cover a range of knowledge and are applicable to the whole business school curriculum, we were curious to learn how the leadership in one discipline (marketing) perceived the role of that discipline in fulfilling the school-wide curriculum mission.

We have organized the research into four parts: a literature review on educa-tional outcomes assessment in general and business education in particular, an explanation of the current AACSB cur-riculum standards, the research design, and a presentation of findings and implications for curricular design and oversight.

Outcomes Assessment Expectations

The issue of educational accountabil-ity is topical, and business education is certainly not exempt (Glover, Blankley, & Oliver, 1995; Smart, Tomkovick, Jones, & Memon, 1999). Sautter, Popp, Pratt, and Mills (2000) reported that recent trends in business education have created increased awareness of curriculum adequacies and deficien-cies. AACSB undertook a vigorous pro-gram to respond to what was seen as a “crisis” and instigated a program in the early 1990s to encourage a more inte-grative business curriculum (Pharr & Morris, 1997).

Can School Oversight Adequately

Assess Department Outcomes?

A Study of Marketing Curriculum

Content

STEPHEN T. BARNETT PAUL E. DASCHER CAROLYN Y. NICHOLSON

Stetson University Deland, Florida

T

ABSTRACT. In this article, the authors examine the key factors that influence student choice of a business major and how business schools can help students make that choice more realistically. Investigating students at a regional university, the authors found that whereas those with better quanti-tative skills tended to major in accounting or finance, those with weaker quantitative skills tended to major in marketing and management. For adherence to the requirements for expanded assurance of learning (out-comes assessment) included in AACSB International’s eligibility standards (2003), the authors suggest that schools of business provide their students with a clear statement of the opportunities and requirements in each business major.

Despite the pressure from accrediting bodies and governmental agencies, Kimmel, Marquett, and Olsen (1998) found that only 42% of the business schools that they surveyed reported hav-ing a comprehensive outcomes assess-ment program (COAP). They found that the incidence of a COAP was related to neither AACSB accreditation nor school status (private versus public). Hindi and Miller (2000) found that the highest ranked uses of outcomes assessment in accounting were for curricular changes. In another survey at the department level, Nicholson and Oliphant (2001) found that almost a third of marketing departments were not using any system-atic assessment beyond course oversight or placement.

If schools that are assessing out-comes do so as part of changing their curriculum and there is a crisis in busi-ness education that most see as curricu-lum based, why are all schools not heav-ily involved in outcomes assessment? We suspect that there are several rea-sons for this lack of involvement: (a) The concept of outcomes assessment is changing, (b) the changes in the concept of outcomes assessment have created goals that are more difficult to assess, and (c) business schools are not orga-nized to effectively assess outcomes.

Outcomes Assessment Is Changing

In the past, AACSB and business schools have focused on the adequacy of inputs—faculty members, library, and research resources. A shift in this emphasis from that of process to one of outcomes assessment is evidenced by added attention to the role of learning objectives in curriculum design (Saut-ter, Popp, Pratt, & Mills, 2000).

More recently, a number of quantita-tive tests have been developed for busi-ness schools, including some coordi-nated through AACSB. Preeminent among these tests are the ETS exam, which assesses content acquisition across the business curriculum, and the EBI Student Satisfaction Survey, which assesses the degree to which the current curriculum meets student expectations. Both tests are notable in that they pro-vide benchmarking opportunities and can be used to identify key areas of

weakness. However, they explore out-comes from the student’s tenure in the business school and collapse across all disciplines. Therefore, they provide only limited curricular feedback to the individual departments and programs within the school.

Although such tests measure knowl-edge, they do not answer two basic questions: (a) What are the most impor-tant lessons? and (b) How well do busi-ness schools prepare their students? Peter Drucker’s perspective on these two related questions points out the rel-evance and complexity of outcomes assessment: “[Business students] have to learn to take responsibility for them-selves . . . [understanding] what [they] should contribute to the organization . . . and [develop a] basic literacy of the organization. . . . and only the students themselves can answer [how well they’re prepared] and they rarely know until ten years or more have passed” (Chapman, 2001, p. 14).

Assessment Is More Difficult

AACSB International recognizes that the curriculum is central in implement-ing a business degree program. The organization specifically pointed this out and underscored the critical role of outcomes assessment: “[C]reating and delivering high quality curricula requires planning and evaluation” (AACSB, 2001, p. 17). It also noted that educational objectives can be realized through use of curricula with different structures and approaches.

AACSB addresses undergraduate curricular requirements in five areas: (a) perspectives on which a business cur-riculum should provide an understand-ing, (b) a general education component, (c) four areas identified as the “founda-tion knowledge for business,” (d) writ-ten and oral communications, and (e) additional requirements consistent with the school’s mission.

Current expectations from accredit-ing bodies and other stakeholders have moved from standards based on reputa-tion and inputs, which are somewhat straightforward for measurement pur-poses, to mission and value-added goals, which are more qualitative and difficult to define. In addition,

curricu-lum development takes place at a num-ber of levels. Within departments, assessments and curriculum develop-ment must take these criteria into con-sideration as educational programs are implemented. A key question for administrators of functional area pro-grams in AACSB-accredited schools is the extent to which the identified core competencies can be or should be relat-ed to the courses offerrelat-ed by that acade-mic area or department.

Assessment and Business School Organization

Outcomes assessment typically is viewed as a college issue, but is this approach the most effective one? AACSB standards suggest that 50% of the content in a 120-hour business cur-riculum should be nonbusiness, 20% should pertain to the Common Body of Knowledge, and the remaining 30% should be taken up by major courses and electives.

Business schools normally use a col-lege level committee to set the standards for the curriculum and to organize the curricular elements, even though the expected outcomes for the different majors vary substantially in perspective and substance. Departmental faculties predictably deal with these variations in expected outcomes by defining and developing courses (and their respective syllabi) to meet what they perceive to be employers’ or graduate schools’ expec-tations for graduates. College curricu-lum committees tend to rely on depart-mental expertise in making curriculum content decisions. Thus, the normal business school curriculum system makes one body (the college curriculum committee) responsible for overseeing the content and standards and gives another (the departmental faculty mem-bers) the authority to create and change curricular content. Accountability prob-lems are not uncommon in organiza-tions that separate authority and respon-sibility in this fashion. We argue that, especially when viewed against a back-drop of increasing expectations for the school and for its included programs, this split is a major factor in the lack of adequate outcomes assessment in busi-ness education.

As we see it, there are two alterna-tives for business schools and curricu-lum oversight. The first approach is to insist that curriculum committees not only take responsibility for interpreting how the curriculum will meet the mis-sion and curricular standards set by the school but also evaluate the actual con-tent of the courses. The second approach is to insist that departments not only decide the actual content of the courses that make up the curriculum but also take responsibility for interpreting how those courses will meet the mission and curricular standards set at the school level. The second method is con-founded by one key question: Are the broad strategic mission standards really applicable at the narrow tactical level at which faculty members determine the actual hourly content for their courses? Or should departments be given the authority to set and oversee standards appropriate for their own programs?

Focusing on this debate between the global and local interests, we decided to explore an undergraduate curriculum in light of the 18 AACSB core standards to determine if administrators perceive col-lege level standards as legitimate out-comes for their departments’ courses.

The AACSB Core Curriculum Standards

Why use AACSB curriculum stan-dards as opposed to some other set of curriculum benchmarks? Ostensibly, assessment mechanisms are in place at the school level for accredited schools of business administration. Thus, the standards create a common language across accredited schools. Degree pro-grams face the challenge of ensuring that the curriculum reflects the stan-dards of an accrediting body. The assumption is that such accrediting bod-ies, because of their exposure to employers and a variety of other aca-demic programs over an extended time frame, are able to set out a comprehen-sive set of curricular criteria. AACSB International is the foremost accrediting body for business schools worldwide. Moreover, because our focus is on the issue of global versus local oversight of curriculum, the school-level standards are appropriate for the study.

Importantly, there are no such curric-ular guidelines accepted across the dis-cipline for marketing or other academic majors at the departmental level. This seems, at first, hard to believe, yet the education arm of the American Market-ing Association (AMA), the area’s pre-mier professional body, lists no such guidelines. In fact, AMA only recently has instituted a professional exam (PCM, Professional Certified Mar-keter), which is more appropriate for practicing professionals than for stu-dents or recent graduates and thus is not particularly useful as an assessment tool for current students.

In setting expectations more clearly, the accreditation standards express the following general and specific items that educators should consider in cur-riculum design:

1. Perspectives that form the context of business: ethical issues, global issues, political systems, social issues, legal issues, regulatory issues, environmental issues, technology issues, and demo-graphic diversity;

2. Foundation knowledge for busi-ness: accounting, behavioral sciences, economics, mathematics, and statistics;

3. Important characteristics: written and oral communications;

4. Additional requirements consistent with the school’s mission: humanities and natural sciences.

It is important to determine how these standards are viewed at the program or departmental level and whether such an assessment can have meaningful, actionable outcomes for curricula. An assessment of these standards indicates that the standards are not noted as equally critical to success when viewed through the departmental lens.

Method

In this research, we explored the per-ceptions of coordinators and chairs of AACSB-accredited marketing depart-ments regarding the coverage of the 18 core competencies. In addition to pro-viding information useful to these chairs for benchmarking in their own programs, the research provides a model that can be applied to other areas within the business school. The research

also allows us to explore how depart-mental administrators evaluate school-level standards.

The current study was conducted via a questionnaire mailed to 322 deans in AACSB-accredited business schools with the request that they forward it to the person responsible for the academic marketing department or area. We obtained usable responses from 111 marketing program administrators, rep-resenting a response rate of 34.5%.

Curriculum Action Index Approach

Gap analyses assess users’ percep-tions of delivered outcomes versus their desired levels. The “gap” between the delivered and the desired is measured, and the larger gaps are viewed as areas in which needs are not being met suffi-ciently. This approach—measuring out-comes against expectations—makes very good sense for assessments. Davis, Misra, and Van Auken (2002) and Duke (2002) noted that gap analysis has sev-eral important benefits in terms of assessments. This method identifies more areas in which improvements can be made—such as retention surveys, exit examinations, or course evalua-tions—than do other assessment tools.

The Curriculum Action Index (CAI) that we use shares a common method-ological perspective with the work of these gap analysts. Where we differ, however, is in the gap that we assess. The most significant difference between the approaches is that ours involves a third key variable in the evaluation—the normative dimension. This approach is based on the expectancy-value models as developed by Fishbein (1967, 1972) and modified by Bass and Talarzyk (1972). A comparison between impor-tance and preparation assesses two dif-ferent, albeit related, domains. CAI, in contrast, measures a delivered outcome (i.e., preparation) against a perceived normative standard for that outcome (how much preparation should have been given); then the gaps are weighted by the importance of the topic, which provides a measure of relative urgency for the perceived gap.

Our instrument asked respondents to evaluate 18 standards on three comple-mentary scales based on (a) how much

of the characteristic is present in their marketing curriculum, (b) how much of the characteristic should be covered in their marketing curriculum, and (c) the importance level of the characteristic. The survey instrument used a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (a minimum amount) to 5 (the maximum amount). The approach involves the following three steps: (a) creation of normative and attitudinal measures called the Defi-ciency Index and Importance Index, (b) conversion of these parametric indices into ranked measures, and (c) calcula-tion of a Curriculum Accalcula-tion Index (CAI) that integrates the two indices and indicates which issues are perceived as most in need of attention.

We first created two parametric indices. The Deficiency Ratio Index (DRI) is a normative index that shows how the respondents evaluated the con-tent delivered relative to the issue. We calculated the DRI as the mean response to the content question “How much is there?” divided by the mean response to the normative question “How much should there be?” Then, we calculated the Importance Index as the mean on the importance question “How important is this issue?”

We then converted the DRI and the Importance Index to ranked measures. Ranks were ordered least (1) to most (18). In the final step, we created a Cur-riculum Action Index (CAI) by multi-plying the deficiency ranking for each issue by its importance ranking. Instead of an absolute scale, the range of CAI scores depends on the number of out-comes evaluated, and we must evaluate the relative differences among the CAI scores. In this study of 18 issues, the worst possible score was 324 (18 x 18 = 324), which would indicate that the issue deemed the most deficient (rank-ing 18 on the DRI) was also the most important (ranking 18 on the Impor-tance Index also) of the 18 issues evalu-ated. The minimum CAI score is always 1 (1 x 1 = 1), which would indicate that that issue was both least deficient and least important. Higher scores are more problematic and indicate the need for review. As a guide, we suggest that issues with CAI scores of 70% of max-imum deserve the most serious consid-eration. However, in a longitudinal

study, any significant CAI increase over time is clearly worthy of review.

Results

Our results suggest that the depart-ment chairs and area coordinators thought the marketing curriculum should and does play an important role in certain curricular areas other than marketing (e.g., economics, account-ing, behavioral sciences, social sci-ences). They also believed that there are other areas (e.g., written communica-tions, oral communicacommunica-tions, ethical issues and technological issues) that the marketing curriculum should address in more depth.

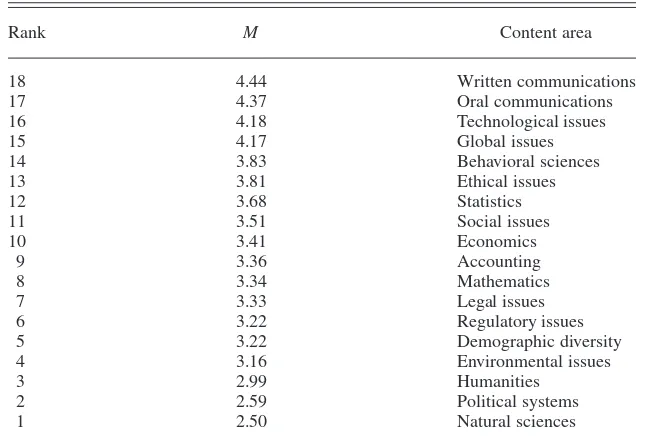

Beginning with perceived importance of the 18 standards within the marketing department, we see that written commu-nications and oral commucommu-nications ranked highest (see Table 1). The mean importance score for written communi-cations was 4.44; the mean importance score for oral communication was 4.37. These items also were among the five areas that the respondents ranked as most deficient. One explanation for this finding is that perceptions that commu-nication skills are both very deficient and very important could result from a perceived lack of these skills in the

stu-dent population as well as from the department’s insufficiency in dealing with them. Although departments agree that all education depends on communi-cation skills, we suspect that the teach-ing of specific skills goes beyond what is offered—or expected—in most university-based marketing courses.

Technological issues (4.18, rank 16) and global issues (4.17, rank 15) were the next most important areas. Interest-ingly, neither of these issues ranked in the top quartile of the deficiency rank-ings; in fact, their deficiency scores were virtually tied (87.95% for global and 87.44% for technological issues). Mar-keting administrators see these issues as important and related to marketing.

The items perceived as least impor-tant included humanities (2.99, rank 3), political systems (2.59, rank 2), and nat-ural sciences (2.50, rank 1). These rank-ings suggest that the marketing educa-tors felt that attention to and integration with these areas would be less important to the success of their students than emphasizing other areas. Given their relative lack of importance, these partic-ular standards perhaps are not espe-cially useful as an assessment tool for the marketing program. Because they are viewed as unimportant, very little energy is likely to be expended to

TABLE 1. Importance Means and Ranks of 18 Core Content Areas for Marketing Curricula

Rank M Content area

18 4.44 Written communications

17 4.37 Oral communications

16 4.18 Technological issues

15 4.17 Global issues

14 3.83 Behavioral sciences

13 3.81 Ethical issues

12 3.68 Statistics

11 3.51 Social issues

10 3.41 Economics

9 3.36 Accounting

8 3.34 Mathematics

7 3.33 Legal issues

6 3.22 Regulatory issues

5 3.22 Demographic diversity

4 3.16 Environmental issues

3 2.99 Humanities

2 2.59 Political systems

1 2.50 Natural sciences

Note. Importance of content areas was ranked on a scale of 1 (least) to 18 (most).

ensure coverage in or integration with the department’s marketing courses.

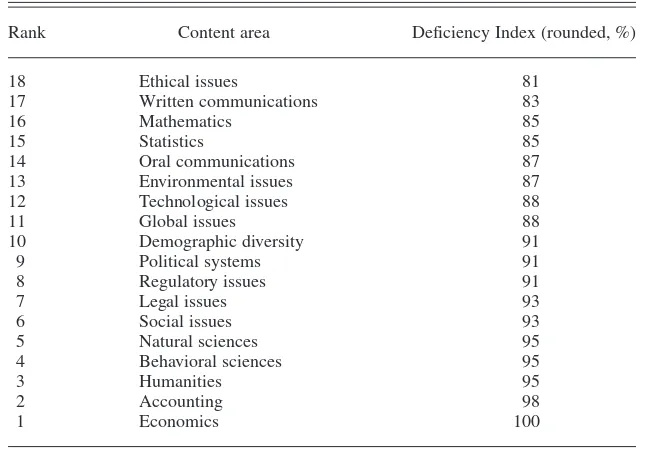

In Table 2, we list the Deficiency Ratio Index in rank order. The results show that the highest rankings (i.e., the ones evaluated as most deficient in con-tent) were given to ethical issues, writ-ten communications, mathematics, sta-tistics, and oral communications. One interpretation of this finding is that these five items exemplify the unique bridging position that marketing holds in the business curriculum, a position that requires the translation of ideas into numbers and numbers back into ideas. Marketing educators perhaps perceive the marketing curriculum as not ade-quately addressing this bridging role.

Items from the AACSB curriculum criteria that were seen as least deficient in the marketing curricula were behav-ioral sciences, accounting, humanities, and economics, indicating that the respondents felt that the marketing cur-riculum is adequate in these areas. Either the respective issues should and do receive sufficient coverage, or they should receive and are getting minimal attention. Regardless of the interpreta-tion, the low Deficiency Ratio Index score represents a match between

department goals and perceived out-comes for these areas.

The Curriculum Action Index scores (see Table 3) represent the combination of the normative opinions and the per-ceived importance. Although one must interpret CAI scores with caution, they do provide several interesting insights. Results draw attention to seven areas of particular concern: written communica-tions (CAI = 306), oral communicacommunica-tions (CAI = 238), ethical issues (CAI = 234), technological issues (CAI = 192), statis-tics (CAI = 180), global issues (CAI = 165), and mathematics (CAI = 128). Each of these areas is essentially an issue relevant to marketing but, other than global and ethical issues, is not typically included in the curricular con-tent of marketing.

Conclusions

We end this article with a beginning. The results of this study suggest benefits from applying the CAI technique to rep-resentative stakeholder groups at spe-cific institutions. Overall, the results seem to challenge basic curricular goals, methods, and models as perceived by the respondents. Although these

chal-lenges may emerge from the marketing curriculum in general, what really mat-ters is the adequacy of a curriculum at a specific institution. Thus, schools would benefit from expanding this study to other programs and specific situations. Luckily, the CAI approach is a flexible tool that can be used with a variety of standards. CAI can be used longitudi-nally to assess whether the market changes are being incorporated ade-quately into the curriculum.

Curricular standards by AACSB are intended to provide guides, not absolute standards. They also are based on best practices and are normative rather than prescriptive. Our reported results con-firm the importance of these attributes to the marketing curriculum and suggest some benefit in using them as an evalu-ation basis. Overall, there appear to be areas in marketing that could benefit from additional emphasis, especially the seven major areas identified. Additional data from other populations such as cur-rent students, graduates, and employers might suggest additional directions. A critical issue remains, however. Because department curricular needs are unique and unlikely to be consistent across the college, broad standards evaluated at the

TABLE 2. Deficiency Indices and Ranks of 18 Core Content Areas for Marketing Curricula

Rank Content area Deficiency Index (rounded, %)

18 Ethical issues 81

17 Written communications 83

16 Mathematics 85

15 Statistics 85

14 Oral communications 87

13 Environmental issues 87

12 Technological issues 88

11 Global issues 88

10 Demographic diversity 91

9 Political systems 91

8 Regulatory issues 91

7 Legal issues 93

6 Social issues 93

5 Natural sciences 95

4 Behavioral sciences 95

3 Humanities 95

2 Accounting 98

1 Economics 100

Note. Deficiency of content area was ranked on a scale of 1 (least) to 18 (most). A higher Defi-ciency Ratio Index implies a greater match between perceived curricular content and the amount that normatively should be included in the curriculum.

TABLE 3. Curriculum Action Index for Marketing Curricula

Content area CAI score

Written communications 306 Oral communications 238

Ethical issues 234

Technological issues 192

Statistics 180

Global issues 165

Mathematics 128

Social issues 66

Behavioral sciences 56 Environmental issues 52 Demographic diversity 50

Legal issues 49

Regulatory issues 48

Accounting 18

Political systems 18

Economics 10

Humanities 9

Natural sciences 5

Note. Higher scores represent greater identified curriculum needs.

college level may be less relevant at the departmental level.

We have demonstrated that depart-ments have the knowledge and drive to evaluate their own curricula against college-level standards and their own internally developed criteria, and our results have some meaning for curricu-lum design. However, it is also likely to be true that these standards, as defined by AACSB, do not capture the richness of outcomes being produced within marketing departments. We assert that departmental involvement in and over-sight of outcomes assessment is crucial to long-term success of graduates. How-ever, if, as research has suggested (Nicholson & Oliphant, 2001), depart-ments are abdicating that responsibility, curriculum revision likely lags behind not only college-level standards but also marketplace needs.

The focus of the educational process is to move students from a level of knowledge and comprehension to criti-cal thinking (Bloom, 1956) that corre-lates with the goal of the program. It is important that AACSB standards and common academic practices provide significant latitude and encouragement to faculty members, departments, and programs for inclusion of curricular ele-ments that support the mission, purpose, and goals of specific programs. Clearly, as our results suggest, marketing

admin-istrators do not view the AACSB stan-dards as equally important. In spite of that, the evaluation of the standards at the departmental level provided a useful perspective on items that are due for curricular review.

Nevertheless, ensuring that program-specific curricular elements are reviewed and evaluated in a similar man-ner, incorporated into a broader business curriculum, and assessed on the basis of outcomes are difficult tasks. It is encour-aging to note that our results, although specific to marketing, suggest that acad-emic department heads are aware of cur-riculum issues. Departmental oversight could be an additional avenue leading to more effective mission-driven curricula.

REFERENCES

The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2001). Achieving quality and continuous improvement through self-evaluation and peer review. St. Louis: AACSB International.

Bass, F. M., & Talarzyk, W. W. (1972). An attitude model for the study of brand preference. Jour-nal of Marketing Research, 9(February), 93–96. Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook I, cognitive domain.New York: David McKay.

Chapman, C. (2001). Taking stock: An interview with Peter Drucker. Biz Ed, November/Decem-ber, 12–17.

Davis, R., Misra, S., & Van Auken, S. (2002). A gap analysis approach to marketing curriculum assessment: A study of skills and knowledge. Journal of Marketing Education, 24 (Decem-ber), 218–224.

Duke, C. R. (2002). Learning outcomes: Compar-ing student perceptions of skill level and impor-tance. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(December), 203–217.

Fishbein, M. (1967). A behavior theory approach to the relations between beliefs about an object and the attitude toward the object. In M. Fishbein (Ed.),Readings in attitude theory and measurement(pp. 389–400). New York: Wiley.

Fishbein, M. (1972). The search for attitudinal-behavioral consistency. In J. B. Cohen (Ed)., Behavioral science foundations of consumer behavior(pp. 245–252). New York: The Free Press.

Glover, H. D., Blankley, A. I., & Oliver, E. G., (1995). An integrated business school model. Management Accounting, 76(May), 35–37. Hindi, N., & Miller, D. (2000). A survey of

assess-ment practices in accounting departassess-ments of colleges and universities. Journal of Education for Business, 75(May/June), 286–291. Kimmell, S., Marquette, P., & Olsen, D. (1998).

Outcomes assessment programs: Historical per-spective and state of the art. Issues in Account-ing Education, 13(November), 851–869. Nicholson, C. Y., & Oliphant, R. J. (2001). How

are we doing? The current state of undergradu-ate marketing programs outcomes assessment efforts. In J. L. Thomas (Ed.),Proceedings of the Association of Collegiate Marketing Educa-tors(pp. 172–175). Association of Collegiate Marketing Educators.

Pharr, S., & Morris, L. (1997). The fourth genera-tion marketing curriculum: Meeting AACSB’s guidelines. Journal of Marketing Education, 19(Fall), 31–43.

Sautter, E., Popp, A., Pratt, E., & Mills, S. (2000). A “new and improved” curriculum: Process and outcomes. Marketing Education Review, 10(Fall), 19–28.

Smart, D., Tomkovick, C., Jones, E., & Memon, A. (1999). Undergraduate marketing education in the 21st century: Views from three institu-tions. Marketing Education Review, 9(Spring), 1–9.