September 2011

United States Government. This publication was prepared by RTI International.*

Overview/Rationale 03

Chapter 1 PSD and Media in Indonesia 05

1.1 Theory and practice 05

1.2 Media and ICT in Indonesia 10

Chapter 2 Kinerja’s Approach and Tools 15

2.1 Media Strategy 15

2.2 Intervention stages 17

2.3 Toolbox 19

Chapter 3 Program Description 22

3.1 Blanket Strategy 22

K

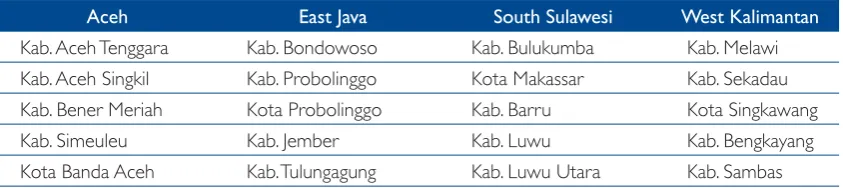

inerja is a governance program focused on improving public service delivery in Indonesia. The program works with local governments to make service delivery more responsive to the needs of its users, while also working with civil society, communities, and the media to build their capacity to demand higher quality services from their governments. Kinerja works in fi ve districts in each of the following provinces: Aceh, East Java, South Sulawesi, and West Kalimantan.Table 1: Kinerja locations

Aceh East Java South Sulawesi West Kalimantan

Kab. Aceh Tenggara Kab. Bondowoso Kab. Bulukumba Kab. Melawi Kab. Aceh Singkil Kab. Probolinggo Kota Makassar Kab. Sekadau Kab. Bener Meriah Kota Probolinggo Kab. Barru Kota Singkawang Kab. Simeuleu Kab. Jember Kab. Luwu Kab. Bengkayang Kota Banda Aceh Kab. Tulungagung Kab. Luwu Utara Kab. Sambas

Media, information, and technology has a critical role to play in this work. Kinerja’s focus on incentives for better performance, for example, works in part by giving citizens a more effective voice in public service delivery, which in turn relies on them having good information about those services, and having viable channels to deliver their feedback. In both cases technology and the media play an important role: technology conveys the information (whether it is by radio, SMS, or Internet) and the media acts both as way of providing relevant information and coverage of the issues, and also as a way of helping ensure those citizens’ voices are heard.

The Kinerja media strategy also focuses on the supply side—helping government Service

Providers gather and deliver information about those services effectively to end-users and to the media. Kinerja also focuses on improving channels for feeding back responses to existing services via complaint handling mechanisms and other feedback mechanisms.

Kinerja believes all forms of media—TV, radio, print, online, community, social—play an important tool in improving public service delivery because a healthy, independent, and professional media forms the main channel of communication between user and provider.

The fact that the project’s target regions span a range of developmental levels and ICT

infrastructure (from rural settings with low access to cellphone signal and media, to urban areas with high penetration of fast data access and services) offers Kinerja a chance to deploy an array of solutions that match the needs and availability of the project’s target groups.

In short, Indonesia offers exceptional opportunities for building on existing media and

communications usage given its geography, its relatively recent embrace of democracy and the way it has embraced mobile data.

PSD AND MEDIA IN INDONESIA

1. 1 Theory and practice

Me dia’s role

K

inerja’s media strategy borrows from both the fi elds of media development and communication for development. As Shanthi Kalathil points out in her book Developing Independent Media as an Institution of Accountable Governance1, these two fi elds are oftenconfused:

Media development is often confused with communication for development, which is a separate but related fi eld. Communication for development typically sees the media as a means to achieve broad development goals, while media development sees strengthening the media as an end in itself.

However, importantly, she notes: “This conceptual distinction is sometimes blurred in practice.”

Kinerja recognizes that it is both advantageous and necessary that media development and communication for development go hand in hand. Strengthening media components as a key partner in the process of improving public service delivery on both the demand and supply sides—is a part of the process as much as communication for development, which usually focuses largely on the supply side—the government provision of services, and getting the government’s message out.

Media, therefore, serves an important purpose in any democracy. The government makes use of the media, through interviews, press conferences and press releases, to publicize, defend and explain the services it provides. Users can have their voice heard through mainstream media directly or indirectly through intermediary organizations such as CSOs.

The media itself plays a proactive role where it investigates issues of mis-governance, corruption and misuse of government funds and, by highlighting their investigations to consumers of their news, brings pressure to bear on the providers of those services. The media also promotes competition by exploring alternatives to those proposed by the government, either from other regions, or from the private sector.

Media occupies what is sometimes called the Public Sphere—the space between state and civil society. “In this space,” in the words of Anne-Katrin Arnold and Helen Garcia, “government and citizens exchange information and services: citizens communicate their demands to the government and, if satisfi ed with how these are met by the government, reward legitimacy to the government in offi ce.”2 The mass media, they state, have traditionally been one of the most

important channels for communication in the public sphere. But they also acknowledge an

important role for communications technology: “In general, citizens cannot make informed political decisions without access to information. ICT plays a fundamental role in this regard, and this role extends beyond the abilities of traditional media.”

This is an important part of the puzzle: the growing use and evolution of communications technologies—ICT, in short—mean that not only is the role of the media changing as these technologies percolate down to even the remotest end-user of public services, but that the technologies themselves make those end-users creators and purveyors of content themselves. This means that while the role of the media changes, so does its relationship with the two other players: governments may no longer see media as retaining a monopoly on information disseminators, and end-users now have other options to convey their views to Service Providers. The equations are changing, even in those areas still considered remote.

Kinerja’s media strategy, therefore, relies on strengthening the media’s role, but also in improving the quality, reach and depth of communication between the three elements: provider, end-user, and the media itself. The more empowered each group is, the better the feedback mechanisms and, thus, in turn, the better the delivery of public services will be.

Me dia roles in PSD

Breaking down the role of media, then, highlights fi ve key elements.

• Information conveyance. Media plays an important role in conveying information about government activities, initiatives, programs and campaigns. We might call this information conveyance.

• Watchdog role. Media also plays an important role in unearthing iniquities in the delivery of services or the performance of Service Providers. We might call this the watchdog role. In July 2007 a local credit union in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, set up Ruai TV and quickly made a mark with its investigative pieces challenging shortcomings in public service delivery. In early 2008, it broadcast a report about a local immigration offi cial demanding a bribe from an Indonesian of ethnic Chinese origin to issue him a passport by citing a New Order law that had been abolished. After the TV station reported the case on successive days, the Governor issued a regulation prohibiting this form of discrimination.

• Feedback role. Media also plays an important role in soliciting, collating and presenting feedback by end-users (or potential end-users, if those public services don’t yet exist) of public services. We might call this the feedback role.

• Response role. Media also plays an important role in seeking comment and response from government offi cials to end-user feedback. We might call this the response role. Sometimes these two roles, the feedback role and the response role, are confl ated when, for example, a media outlet broadcasts a town-hall meeting, a story about a particular issue contains both details of the feedback from the end-user, and the response from relevant offi cials, or a newspaper has a running letters page where offi cials are in the habit of posting responses. An example of this is in Makassar, South Sulawesi, where the Tribun Timur, the Kompas Group’s local daily, has since its inception in 2004 dedicated a space to publish questions from readers and responses from government offi cials about public services. The section is so popular it has grown from a quarter page to two pages. It engages readers because it seems to work: things get fi xed—not least because the local mayor is a reader who follows up complaints with the relevant offi cials.

• Campaign role. Media can also play an important role in mobilizing end-users of public services when changes in behavior are sought, for example, in disposing of waste or promoting breastfeeding. Although connected to information conveyance this is usually a longer-term process, and has less to do with simply providing information but in building the support and awareness necessary to modify behavior. We might call this the campaign role. It should be pointed out that such campaigns can also be directed at the provider of public services, when public opinion seeks to change policy or shame offi cials into changing behavior. An example of this might be reducing teacher absenteeism.

Ho w effective is media in PSD?

There is some academic literature examining media’s impact on public service delivery but the answers aren’t always conclusive, suggesting that we have to be careful about assuming a media strategy is going to have a specifi c effect.

It’s clear, therefore, that more research is needed, especially given the fact that advances in

communications technology are rapidly altering both the nature of “media” for urban communities, and access to telephones and other basic IT services for even the most far-fl ung rural dweller. Research from ten years ago may well be valid today, but we need to have a clear understanding of what has changed on the ground in the meantime, and how that may change the conclusions.

We can, however, reach some tentative conclusions that have informed our selection of tools, approaches and priorities.

Information campaigns, for example, work better where there is more media, but they also work better when accompanied by efforts to mobilize end-users.

Information campaigns are usually directed by government and aimed at altering behavior.

Research suggests they’re quite effective: a campaign in Uganda on the leakage of school grants by district offi cials—with some 80% of so-called capitation grants to schools going missing—led to an impressive reversal, so that after the campaign only 20% went missing.3 Clearly the campaign 3 World Bank (2003) World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for Poor People. World Bank and

worked: it also proved that the more media—in this case, newspapers—there was in the district, the greater the impact, suggesting that it’s in the government’s interest to encourage a vibrant and extensive media.

But other research seems to contradict this: information campaigns to encourage education in India have had more mixed results: one had no impact on learning in public schools, while another had an impact on teacher absenteeism, but little impact on actual learning. The conclusions from such studies were that information campaigns needed to be accompanied by efforts to mobilize communities in order to see improvements in health levels and the provision of services. In short, itÊs not sufficient in itself to launch a campaign to raise awareness, but also to work towards creating or supporting mechanisms that promote activity among end-users. We see this as an important indicator of the importance of supporting feedback mechanisms and monitoring that are done by the end-users themselves and covered by local media.

ItÊs also important to understand the local context and commercial imperatives of any partnering media. They may or may not be interested in playing a more traditional media role if it endangers relationships with existing sponsors. For example, recent research in Benin by Philip Keefer and Stuti Khemani4 of data from 4,200 household and 201 villages, highlighted the

different agendas of community radio stations, depending on where their fi nancing was coming from. When the goal is to improve public participation and demand for improved services (what some call “accountability-based programming”), that may not necessarily jibe well with outlets which depend on government and aid organization funding either directly or indirectly through government- or donor-provided programming. Their fear, the researchers noted, may be that any programs that appear to question government performance could jeopardize this important source of income.

On the other hand, purely commercial stations may have the opposite view: programming which may be, if not controversial then at least a little more combative, could appeal to listeners and draw advertisers and develop a healthy independence from government. The bottom line is that working with community radio stations requires a strong understanding of the context in which they operate, the local conditions and the impact of existing content.

The same research highlighted another challenge: itÊs not always enough to simply channel „messages‰ through community radio and assume a particular outcome. The researchers noticed that those communities with access to community radio tended to take to heart programs about education, but not in the way they’d expected. Instead of increasing collective demand for improved educational services, they instead tended to invest privately—in other words, outside the government system—in their children’s education. The lesson here is that programs need to be interactive and participative, and spread over suffi ciently long period that the listeners become invested in the outcome: this can be achieved by ensuring that programming includes the experiences of other, but similar, communities, and, as important, that participants’

feedback and questions are responded to by someone knowledgeable. (See our Community Radio pilot project for more on this.)

Measuring the impact of media on responsiveness to public services isnÊt necessarily quantitative. Research in Indonesia has suggested that increased exposure to media—in this case, the proliferation of TV channels in Java—may work against increased participation in the monitoring of public services. But the conclusions one might draw from the research are varied and perhaps more nuanced. Benjamin A. Olken in East and Central Java5

showed that the more television signals there were, the longer people watched TV and the fewer social groups there were in a village—including, in some areas, lower participation in village development meetings. But this didn’t mean that governance suffered: although fewer people turned up to meetings about a local road project, it did not mean that more corners were cut in the project through corruption than would be expected.

The conclusions one might draw from this are interesting. Although some have been inclined to see it as the inevitable decline of social participation in communities at the hands of mass media, other possibilities suggest themselves: for one, attendance at meetings is not necessarily a good indicator of social participation. Olken measured the decline in social participation in terms of villagers joining fewer social groups—including community self-help activities—the more TV channels were available. These included neighborhood associations, school committees and informal savings groups. But if the building of the road under these conditions of lower quantity public monitoring was no more plagued with corruption than when public participation in the monitoring groups was higher, one could conclude that in fact the quality of monitoring was less affected than might appear to be the case.

Olken also reaches a tentative observation himself: “social capital”, or public participation, is not the only way people’s civic consciousness is raised. “though television and radio broadcasts are largely national, and rarely if ever report on individual villages,” he writes, “it is of course possible that media exposure affects village level governance through channels other than social capital.” In other words, by watching more TV, villagers may raise their appreciation of governance issues through a more indirect exposure: watching TV that addresses the issues, either through national news programs or drama—sinetron, in Indonesian parlance—that may touch on locally relevant topics, such as corruption.

Alternatively, of course, those people who attended the planning and monitoring meetings were the “hard core” who would attend anyway, and the others were there as spectators. When something better came along to watch, they stayed home to watch it. Indeed, Olken notes that in fact the number of people who spoke at the meetings did not change, despite the lower attendance. Indeed, the meetings were little changed: “Even though it reduced attendance at meetings, greater television reception did not change the number of people at the road-building meetings who talked, the probability that a corruption-related problem was discussed at a meeting, or the probability that the meetings dedicated to project accountability voted to take

any serious action, such as fi ring someone or calling for an outside audit, to resolve a problem that public participation in meetings is not an indicator of village governance.”

Although he does not make this conclusion explicitly, it might be argued that and that public participation in meetings is not necessarily a good indicator of the villager’s interest in the topic: it was either unchanged by the increase in TV viewing or that person felt their interests were well represented by neighbors. As villagers get access to more sources of information through greater TV and radio access, they don’t feel the need to attend and sit through every planning meeting. For our media strategy, the lessons are perhaps that we need to be careful what we measure: it’s not enough to count the number of hits a Facebook page has, or the number of letters sent to an editor. If end-users feel their views are represented, and feedback is being conveyed successfully, it may not be necessary to add their voice.

Indeed, this media strategy is guided by the notion that the more media there is in a community the more the public tend to identify with the provider of services. Leonard Wantchekon

and Christel Vermeesch, also based on research in Benin, looked at the relationship between membership in information and social networks and the demand for public goods—in other words, whether there was a connection between people using media outlets as sources of information, participating in communal and political life and connecting to the outside world, and their demand for public services (a road, better education, health services etc.) They tentatively concluded the following: “Media outlets not only affect the nature of the agency relationships between governments and voters, but also may induce voters to have a stronger preference for national public goods.” In other words, the more end-users were exposed to media the more they tended to identify with public services (in contrast to, say, using private services—transportation, education, health etc—or not feeling they in some way “own” the services and therefore have a say in them. “In fact,” the researchers concluded, “one may argue that access to media affects accountability partly because it makes voters more public spirited.”6

1. 2 Media and ICT in Indonesia

Below is an overview of the evolution of media since the fall of Suharto. While such an overview suggests obvious potential, it also presents some hazards.

Ne wspapers

Despite commercial pressures, there are now around 1,000 publications across the country— more than three times that in 1998. There are caveats: this has not resulted in a similar increase in the number of copies printed or circulated—14.4 million were being printed in 1997, rising to about 19 million in 2009, 70% of them delivered inside the Greater Jakarta Area. And, after an initial mushrooming of locally owned media in the late 1990s, ownership has consolidated, with two players, Kompas Media Group and the Jawa Pos Media Group, dominating the fi eld. However, with Indonesia boasting an adult literacy rate of 92%—as high as Malaysia’s—newspapers

represent the dominant media in Indonesia, and an important channel for improving public service delivery.

Ra dio

Radio, too, is diverse and growing. The number of radio stations has increased from 700 during the Suharto era to more than 2,500 as of 2009, the majority of them privately owned. One network, KBR68H, provides content to about 600 of those stations. There are several hundred community radio stations, usually owned by the local communities they serve.

Te levision

Television has expanded hugely as well. Only six TV stations were permitted during the Suharto era, all of them national—local stations were not permitted. Now there are more than 60 national stations and more than 100 local stations shared among a variety of owners, including NGOs.

In ternet

The Internet has grown signifi cantly, coinciding with political liberalization, which has ensured a minimum of government interference in content (compared to, for example, Thailand and Malaysia). In 1998 there were about half a million users in Indonesia; now, according to one estimate, there are about 40 million out of a population of about 245 million. Given that there are some 35 million Facebook users in Indonesia, that seems a conservative estimate. Indonesia, however, remains behind on the spread of fi xed broadband, at only about 2.8% households— behind India with 3.8%, and well behind countries like Vietnam (16.5%) and the Philippines (10%).

Indonesia is among the world’s top fi ve users of Facebook and Twitter. Facebook has been a key mobilizing tool in several high profi le cases. In the case of a woman who was being sued by a hospital for allegedly defaming it in an email, more than 1 million Facebook users came out in her support. One page supporting two deputy commissioners of the national anti-corruption agency attracted more than 1.3 million members.

Mo bile phones

Mobile phones have become ubiquitous in Indonesia, not only as a telephone but also as portable computer and Internet device.

More than 70% of Indonesians had a cellphone in 2009, according to World Bank data, compared with less than 30% in 2006. That’s more than Puerto Rico or Egypt. One estimate, by analysts Frost & Sullivan raised that estimate to nearly 97% by the end of 2010: in other words, there are not many Indonesians left without a cellphone, or at least access to one.

Indonesian counterparts on SMS concluded that “Indonesian researcher SMS use in many ways mirrored Australian researcher email use.”7

SMS remains a key and natural form of communicating information and data for many Indonesians, which is why the country is embracing wireless broadband—accessing the Internet from a

cellphone or a wireless dongle attached to a computer—more quickly than many of its neighbors. While less than 1% of Thais or Indians use wireless broadband, and less than 9% of Vietnamese and Filipinos have it, more than 17% of Indonesians use wireless broadband—that’s more than 41 million people accessing the Internet from their cellphone. (See chart)

Telecommunications Industry

Source : Frost & Sullivan, Jan 2011, Indonesia

This is driven by a number of factors.

• Cost: Indonesia has one of the lowest Average Revenues Per Unit in the region.

• Early adoption: Indonesians took quickly to cellphones because they had been starved of landline telecommunications for so long: Indonesia had roughly the same number of landlines per capita as China in 1991—seven for every 1,000 people; a decade later China had 140 per 1,000 people, while Indonesia had a quarter that, according to ITU data:

According to ITU Data:

Source : United Nations (citing International Telecommunications Union)

• Early adoption. For many Indonesians the cellphone was their fi rst computing device. Indonesia experienced relatively low growth in home computers: in 1997 it had more

computers per capita than China or Vietnam. By 2003 both countries had overtaken it, and by 2006 China had three times as many, Vietnam nearly fi ve times.

Personal Computers (per 100 people)

Source : Gapminder Foundation (citing UN data)

• Indonesian language is readily abbreviated and so lends itself to the short 160-character format of the SMS message. It is also written in roman script, and therefore, like Tagalog, required no special software either on the network or handset side (unlike Thai, or Vietnamese, for example).

Li mitations of media

It’s clear from this that both conventional (or institutional) media and social media/mobile media are rich sources of connectivity in the public sphere: both via traditional media techniques and through the more direct path of end-user interacting with provider. But there are limitations.

On the one hand there’s a competitive and lively environment in which outlets are eager to differentiate themselves from each other, which provides opportunities for bolstering the participation of media in the roles described above. Opportunities might include:

• Greater choice of partnerships.

• Encouraging competition among media outlets to improve quantity, quality and depth of coverage. If one outlet, for example, is covering a particular aspect well, they are likely to gain followers (readers, listeners, viewers), and this will encourage competing outlets to follow the story. They may try to match the story (in other words, cover the story in a similar way) or they may try to pursue a different angle (a different approach to the story), or they may try to “knock down” the rivals’ story (i.e. try to show it’s not true). All of these approaches benefi t the issue because they result in increased coverage, and, over time, more informed coverage, as journalists understand the issue better.

On the other hand there are limitations. The fi rst is capacity: there are an estimated 30,000 journalists working across Indonesia, only a small proportion of whom are experienced, skilled and producing high quality content. This is primarily due, according to Tessa Piper of MDLF, to an absence of any formal in-house training, university journalism courses or long-term training programs by external or internal organizations.8

The second is funding. Journalists are generally very poorly paid in Indonesia.

Together these factors contribute to several problems:

• Journalism of poor quality, reducing respect for the profession among the public and local government.

• ‘Envelope journalism’ where journalists receive cash for attending press conferences or providing coverage of companies, individuals or events. This also reduces the effectiveness of the media’s role as a credible intermediary, and reduces respect for the profession as a whole.

KINERJA’S APPROACH AND TOOLS

O

ur strategy and toolbox, therefore, must be fl exible and copious enough to be able to anticipate the breadth of variety in the areas Kinerja covers, as well as the likely advances in media and ICT usage during the course of the program. What may work well in Makassar may not work in rural East Java; what may work well now in a district in Aceh may be superseded by the expansion of 3G phone networks and falling handset prices in the next 18 months or so.Because of this, we have chosen some districts for pilot projects based on their current state of media and ICT penetration. We will pursue specifi c approaches there in the hope of honing our tools and learning before applying them more broadly. For all districts, however, we will apply a uniform, or blanket approach, where baseline tools will be used across the board.

2. 1 Media Strategy

Kinerja sees media and information communications technologies as key to building connections between the supply and demand sides of public services. In other words, the public need to know more about the services they’re entitled to, and the provider needs to know more about how the end-users feel about those services. The media plays a vital role in making this happen.

Central to our strategy, therefore, is improving the media’s role in this process. This means improving the quality of information about public service delivery and its quantity. In short, by ensuring that end-users are better informed about public services available to them, and the Service Providers are better informed about the end-users’ experiences with and attitudes towards those services, there will be a greater likelihood the services will improve. We see this not just as a question of focusing on media: for the strategy to work well it needs to also focus on improving the quality of information moving between the three main groups: Media, Service Provider and End-user.

• Service Providers: capacity building of Service Providers in media. Journalists are only going to be as good as the material they are able to work with. On the supply side— government—this means Service Providers can be helped to do a better job of informing journalists and helping them get the material necessary to produce more useful content.

• End-users: developing feedback mechanisms and complaint handling mechanisms. Local government offi cials cannot and should not rely solely on media to represent the views of end-users. They need to be able to hear from end-users in as direct a fashion as possible about their experience with public services in order to be able to make good choices about tweaking those services or responding to individual problems. This is where feedback and complaint handling mechanisms come in.

ICT

We also view ICT as integral to this. The fast evolving world of social and community media rely for their growth on the expansion of telecommunications, Internet and affordable tools for creating, distributing, sharing and storing content, information and multimedia. Indeed, the spread of conventional media networks and channels have much to do with the growth of affordable technology—such as KBR68H’s groundbreaking use of MP3 fi les to distribute its content over poor connections around the country.

Guiding principles

Our core principles in working with ICT and media are built on existing practices. That applies to both media and ICT. For example, Kinerja sees usage of appropriate technologies and already adopted communication channels (BlackBerry messenger, community radio, Facebook and SMS, for example) as a key principle in its media strategy. However, we also recognize that communication technologies are changing rapidly, and so we hope to build into our planning anticipation of their further evolution, spread and adoption in a country known for its early and enthusiastic embrace of advances in communication technologies. For example, Facebook is presently only appropriate in urban areas such as Makassar, but as the project progresses usage is expected to spread to more rural areas, increasing its applicability and creating opportunities to apply lessons learned and resources developed in those areas of early adoption.

2. 2 Intervention stages

We’ve looked at each intervention and identifi ed steps that they all have in common, and which could be considered to be relevant to media and ICT. The process is similar whatever the intervention: a media component, followed by an implementation.

Raising awareness of the issues involved (and encouraging end-users to share their experiences about the service in question).

Second, in consulting the public as part of the process of seeking buy-in and input for the intervention.

Thirdly, once agreed, the intervention needs to be publicized as broadly as possible, along with any details and information pertinent to the public. This step also includes information provision where media tools ensure that stakeholders have access to the information they require when and where they need it.

Finally, the media strategy for each intervention includes procedures and tools for setting up mechanisms for complaint handling, and feedback generation.

This is perhaps best understood by describing the process (not all interventions will include all steps, or some steps may be abbreviated, but they all follow a similar path).

Any intervention begins by raising awareness among the public of the issues involved, and encouraging end-users to share their experiences about the subject in question. For example, in the School-Based Management project (SBM) Intermediary Organizations, assisted by District Coordinators, will conduct workshops with stakeholders at the district level to share Good Practices. The Media Intermediary Organizations will coordinate with the Service Providers to help raise awareness of this among stakeholders and the broader public.

This is followed by a planning stage. In the SBM case this will be the development of District head decrees (SK Bupati/Walikota) related to SBM.

Then there’s a consultation period. The object would be to create a virtuous circle of discussion where as many stakeholders as possible are consulted on the proposal and their opinions

recorded and fed into the consultation process. Tools for this include all media outlets, but also discussion for online, physical gatherings and low-level media (community media). After that broad agreement is reached. In the SBM case, this will involve working with media to achieve as broad a range of opinions as possible.

Then there’s the agreement process: this is when the actual intervention is decided upon and decrees by SK Bupati/Walikota are drawn up.

initial awareness of this as a ‘development’ in media terms, but recurring content that would serve to remind interested parties of the existence of the service and/or intervention. Tools used during this stage would be above the line (media) but also below the line, reaching directly to end-users via community radio and other low-level tools. In the SBM case this would be working with media and other partners to publicize the intervention and to promote ways of monitoring and offering feedback on its implementation (charters, complaint handling mechanisms, etc).

Next the intervention is implemented. In the SBM case this is the institutionalization of a planning and budgeting process.

Crucial now is the feedback/monitoring stage, where end-users are encouraged to monitor performance and offer feedback on the implementation. After the public awareness have been built and the services start delivering to public then it should have system and procedure for public to respond the quality of services as well as monitor whether it already followed up by the service units. The project will assist the Service Unit to have better mechanism on handling feedback from public and develop openness monitoring scheme with media involvement. In the SBM case, this will involve Kinerja working with media outlets and citizen journalists to strengthen their role in improving transparency and control, as well as helping in the creating of Complaint Handling Mechanisms based on the creation of Service Charters in Schools. Intermediary Organizations will also monitor the progress of SBM in partner schools using media and service charters agreed to by stakeholders.

Media partners will be involved in the replication stage by creating content and coverage opportunities for media of those schools chosen to be learning centers for SBM.

Graphically, it looks like this:

Awareness

Plan

Consultation

Agreement Publicity

Implementation Feedback/ monitoring

2. 3 Toolbox

Our toolbox, as mentioned before, straddles the fi elds of media development and

communications for development. We also intend to include technical development support, particularly in those pilot project cases where solutions are likely to be more customized and not necessarily something that can be sourced off the shelf.

Creation. Kinerja and/or its partners will be responsible for creating a resource of material that can be used by all stakeholders in the creation of content, be it press releases, stories and frequently asked questions (FAQ) lists. It will also create content guidelines for its media partners to help standardize the development of subsequent content. This is important to ensure that trainers, journalists, public information offi cers and other stakeholders can get good quality information when they are creating content.

Partnership. Kinerja will establish guidelines for establishing media partnerships with mainstream media, social media and community media to raise awareness.

Facilitation

Capacity building. As mentioned before, the level of training and expertise available to most journalists in Indonesia is low. This is also true of media skills for most public offi cials, who receive little or no training in corralling information for public consumption and dealing with members of the press or public.

So our training toolkit will be an important step in any such intervention, involving workshops focused on training/mentoring the following groups:

• Journalists;

• Future journalists, non-professional journalists, community journalists; • Editors and other content-related management executives;

• Service Provider Information Offi cers and public information offi cers; • NGOs and other stakeholder groups.

The modules offered will include: • Basic reporting skills;

• Investigative reporting skills; • Ethical training;

• Multimedia skills, including web, video and audio;

• Re-purposing skills, including how to convert content in one format to another, and how to make such decisions;

• Intervention-specifi c reporting, including understanding international, national, and local level data and issues;

• Media handling;

• Social media training including the use of Facebook, Twitter, BlackBerry Messaging (BBM) and mig33 for disseminating content, running groups/pages and handling requests and feedback;

• Information access: how to build systems and processes to provide regular information access for end-users, in the form of websites, SMS response services (send a query by SMS, and get an automated response).

Technical development and facilitation

Beyond training Kinerja will provide assistance in technology and communications where applicable. Our tools here include:

• Audio editing and compression software (Audacity etc): how, for example, to edit audio and save in small, manageable formats; and

• Transmissions and delivery.

Facilitation

Other tools include:

• Establishing prizes/competitions for reporting; and

• Establishing media forums, either physically or through the outlets (online, radio phone-ins, live broadcast of town hall meetings etc) to build longer-term interactions between user and end-user.

Sp ecifi c tools

Here are some examples of more specifi c tools we plan to deploy. More detail is provided in Chapter 3.

Community radio network

Kinerja will work with existing community radio stations to build, or expand, their networks in creating and sharing content relevant to the interventions. Through a combination of capacity building and technological assistance, Kinerja will help to raise the quality of content and ensure that the content was accessible to more end-users. In turn government representatives will be invited to contribute responses and discuss their work as part of the program, creating a feedback loop. End-users from one community will benefi t from hearing experiences from those of

neighboring communities.

For example, a show of one hour could be made up of smaller contributions from community stations within a network, which will be edited into one program and then distributed among the network members. This editing and redistribution network could be established in a number of ways, depending on the availability of communications, facilities, and capacity.

Ra dio program multiplier

attracting such broad coverage; sometimes the quality of media is uneven and inviting weaker outlets to press conferences, interviews etc. creates poor content and contributes to greater misunderstanding and/or negative perception of the issue. Also, such an approach tends to miss the possibility of making use of the nature of media, which is highly competitive and driven by what are perceived to be the most exciting and prominent stories of the day.

For this reason we are pursuing a strategy in some districts of working with one key media

partner owner and helping them to create content that is suffi ciently compelling and relevant for it to ‘lead’ the local news agenda and then be pursued by other outlets. By concentrating efforts and resources in this way Kinerja hopes to:

Ensure the quality of content and its publication in accordance with the intervention timeline;

Stimulate interest in and demand for content on the issue among other media players;

Create quality content that could then be repurposed by other media outlets within the partner group, or elsewhere.

Ci tizen journalism

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

T

he media program is, as discussed above, broken down into two sections: the blanket approach, which covers all districts, and a cluster of pilot projects, which cover a few targeted areas.3. 1 Blanket Strategy

Each district will have the following:

Media training. Kinerja’s local partners will work with media and Service Providers to provide training to help lift the quality of their output. For media (and for citizen journalists etc), that means journalism training, as well as more specialized courses in the ins and outs of the three interventions—business, health and education. For Service Providers, it means helping them work better at handling requests for information from the public and from journalists, and to help them forge productive relationships with both.

Content dissemination. While capacity building is important to improve the quality of information, it’s limited unless efforts are made to improve how information moves around. It’s no good, for example, for a journalist or citizen journalist to write a great story about breastfeeding if only a handful of people read it because it was only posted on the wall of one village. Core to Kinerja’s vision is the idea that information must be used and re-used liberally in order for it to reach as many people as possible. This means improving the reach of media outlets’ (and citizen journalists’) content by partnerships with other providers (for example, a piece broadcast on one community radio station being rebroadcast on another; by repeating content; by advertising the content on social media (Twitter, Facebook etc); syndicating the content through partnering outlets or converting content from one format to another (a radio piece, for example, to be transcribed and republished on a blog). Kinerja will therefore enable discussions, workshops and ancillary training for media practitioners to help them repurpose content (in other words, to fi nd ways to re-use material they’ve already produced). Expanding role of media via forums. Media will also be encouraged to build partnerships and extend their role by inviting them to participate in forums with other stakeholders—NGOs, End-users, Service Providers. This will help to extend their coverage of the issues related to Kinerja’s interventions and help to stimulate discussion further. It may also contribute to closer partnerships with NGOs by media, which is already a feature of Indonesian local media.

These three elements are explored in greater detail below.

Ca pacity building of media professionals, with optional modules/inclusion of

able to research, report and create content of suffi cient quality that it informs the end-user about the key topics covered in the intervention areas. It will also be hoped that editors and senior reporters will participate in the process so that they, too, could assist in raising the quality of public discourse about the topics in question.

The process will break down as follows:

The Media Intermediary Organizations will receive initial training, material and guidance in the capacity building process. They will then set up and manage training courses for journalists after securing buy-in from editors. The courses will cover the following four modules:

• Basic reporting and writing (general). This need not be a bespoke module: the goal is to ensure that all participants have reached a certain benchmark in terms of basic journalism skills.

• Advanced content generation. This course will cover multimedia reporting and be more specifi cally geared to local conditions and the local media landscape. Ideally it will be led by someone who was well versed in the context in which the journalists attending operate (fi nancial, political, geographic, social, economic.) The goal would be to offer journalists and other participants more tools and ideas about how to move beyond simple coverage of press conferences and government events, but motivate them to generate more interesting content—columns, photo essays, multimedia stories etc.

• Intervention topics. This course will explain the background of the overall topic under which the intervention is included. For example: School-Based Management falls under Education, so the following topics will be included in the module: education in general; Education in Indonesia; Education in the province/district; then the specifi c context of the intervention—organizing curricula etc. Then the intervention itself will be covered. This module may be provided by an Intermediary Organization with suffi cient expertise to be able to fi eld questions, or even someone from the centre, or Service Unit, depending on availability and resources. Content for this course will be provided from Kinerja resources. The goal will be to ensure that all participants in the course were well informed about the issues and their broader context.

• Covering intervention topics. This module will address the intervention topic from a journalistic point of view. What are the key issues? How might they be covered? Who would be the primary sources for such coverage? The goal of this course will be to apply lessons learned in the fi rst three modules to the nitty gritty of covering the intervention topics in their media and to encourage innovation in the way these topics are covered.

Depending on interest and resources, these modules could be taught separately or as one contiguous course. They could also be broken down by participant.

• Bloggers and other digital media content producers. These courses will focus on generating high-quality products and establishing norms for online content production.

• Specialized „beat reporters‰. If reporters already focus on the intervention areas (education, business, health) or if editors are interested in assigning reporters to focus on these areas, then courses could be tailored for their needs.

• University staff. If journalism courses exist in the target provinces, it makes sense to reach out to those lecturers involved and include them in this process by inviting them to attend and otherwise participate in the courses. Not only could they then become sources and contributors to the media organizations themselves, but they might then also motivate students to cover the topics upon graduation or while interning.

• Local trainers. If media outlets have their own staff involved in training, then special courses could be provided to assist them in internalizing/institutionalizing the lessons provided. This will help spread both the knowledge and also the cost of providing such training.

• Media business professionals. Any sales/marketing/promotion staff could be offered similar training in at least some of the modules in order to motivate them to identify possible commercial opportunities in expanding coverage on the intervention topics.

Public Information Offi cers/Service Providers

The goal in training PIOs will be to ensure they are best equipped to handle requests for information from journalists and the media, as well as to generate, organize and disseminate content related to the interventions. The fi rst four modules are similar to those offered to media:

• Basic content writing (general). This need not be a bespoke module: the goal is to ensure that all participants have reached a certain benchmark in terms of basic writing skills. (This module will not be dissimilar from the fi rst journalism module, although it will of course be geared more to the preparation of website content, FAQs, press releases and material designed for public consumption. It will emphasize simplicity, clarity and using language that the likely readership—i.e. local people—would be familiar with and relate to.)

• Advanced content generation. This course will cover creating multimedia content and be more specifi cally geared to local conditions and the local media landscape. It will be differ from the journalism module in that it will be aimed at PIOs creating compelling content based on the guidelines set by their department but it will stress the same basic elements and should be led by someone who was well versed in the context in which the end-users—both public and journalists—operate (fi nancial, political, geographic, social, economic.) The goal will be to offer PIOs other participants more tools and ideas about how to move beyond simple press releases and other offi cial content, and motivate them to be more imaginative in getting the message out.

module may be provided by a Service Provider with suffi cient expertise to be able to fi eld questions, or even someone from the centre, or Service Unit, depending on availability and resources. Content for this course will be provided from Kinerja resources. The goal will be to ensure that all participants in the course were well informed about the issues and their broader context. This module can be identical to that offered to journalists.

• Publicizing intervention topics. This module will address the intervention topic from a media handler’s point of view. What are the key issues? How might they be socialized? Who will be the main targets for such content? The goal of this course will be to apply lessons learned in the fi rst three modules to the process of ensuring the intervention topics are properly understood by both media and the public and to encourage innovation in the way this is achieved.

• Media practice and strategy. This module will provide the basics in how journalists work, their priorities and needs, and how these needs might best be met by PIOs and other public-facing government offi cials. It will also focus on developing media strategies to support promotion of programs and activities conducted by Service Providers in the intervention sectors. Key to this is developing and organizing content that can be drawn upon in response to questions and requests, and can be accessible to journalists when and as needed (in for example, a website). It will also cover building partnerships with media to generate recurring content, such as a regular phone-in or forum.

• Public query practice and strategy. This module will look at the informational priorities and needs of the end-user (public), and how these needs might best be met by PIOs and other public-facing government offi cials. It will focus on developing strategies to promote programs and activities conducted by Service Providers in the intervention sectors. Key to this is developing and organizing content that can be drawn upon in response to questions and requests, and can be accessible to members of the public when and as needed (in for example, a website or through SMS/phone requests). The module will also address how best to feed information from the public back through the system to ensure that services are improved.

Co ntent dissemination

Capacity building

The goals of these training modules will be to boost the capacity of media—conventional, social, community—to convert, share and re-use existing content, in order to maximize its value and reach. These modules could also be provided to PIOs/Service Providers if desired.

• Content conversion. This module will focus on how to convert content from one format to another. It will also focus on the potential benefi ts of doing so, and the various options available (and their aesthetic, journalistic and audience-enhancing merits). The tools involved will be geared to the requirements of the media involved (for example, open source software to minimize cost, and the reduction of fi le size of multimedia elements to reduce download/ streaming resources, as well as the likely needs of the end-user). Conversion examples include: audio to text (transcription); video to audio; photos + text to slideshow. The module will also cover the journalistic and technical aspects of compressing content, both in terms of fi le size and in length. For example, a press conference of one hour down to a two-minute segment, or a high quality video down to a format that allows it to be viewed on a feature phone.

• Content sharing. This module will focus on how content could be shared with other media partners in the same or other sectors. This will cover the practicalities of setting up such arrangements and the benefi ts thereof. The module will include

- Technical procedures for sharing content. How to save and distribute content using communication technologies (Internet, email, fi le sharing, GPRS, RSS) and transportation (car, bike, person, pigeon). How to combine content where necessary or desirable (for example, to concatenate two audio items from separate sources on a similar subject).

- Arrangements. How to set up such arrangements so they’re mutually benefi cial and sustainable. How to decide on formats, length, attribution and co-branding.

• Content re-use. This module will focus on how to re-use existing content from one’s own organization, or shared content from media partnerships. It will include modules on how best to use social media (Facebook, Twitter etc) to promote this content and how to break it down into chunks suitable in size for dissemination on social media. It will explore the media principles of such content re-use—when and how to do it, how to avoid user fatigue, how to avoid cannibalization of content which is generating revenue.

Partnership facilitation

This part of the strategy focuses on the social aspects of building the partnerships necessary to ensure the broader dissemination of content described above. It will entail Media Intermediary Organizations undertake the following:

• Assess the existing media landscape and assessing potential partnerships • Arrange meetings between media outlets identifi ed as potential partners • Offer and organize training in the above courses as required

Technical support

Media Intermediary Organizations should also provide a basic level of technical support beyond capacity building and partnership facilitation to ensure the partnerships are not limited by technical issues. This support will be provided by some or all of the following initiatives:

• Website forums and FAQs, including case studies and how-to guides

• Stockpile of appropriate tools for usage: software, basic hardware, cables, etc

• On site visits by technical support teams/individuals to help overcome problems that media practitioners cannot solve on their own.

Ex panding role of media via forums

Media will also be encouraged to build partnerships and extend their role by inviting them to participate in forums with other stakeholders—NGOs, End-users, and Service Providers. This will help to extend their coverage of the issues related to Kinerja’s interventions and help to stimulate discussion further. It may also contribute to closer partnerships with NGOs by media, which is already a feature of Indonesian local media.

This will be done by extending the facilitation modules for content dissemination to partnerships outside media. These partnerships may include the following:

• NGO as owner/shareholder in media. NGOs can provide funding to support media organizations, or programming. In Southeast Sulawesi, for example, an NGO called Yayasan Yascita set up a radio station (Radio Suara Alam) and a TV station (Kendari TV) in part to boost coverage of environmental issues.

• NGO as content provider. NGOs can take the initiative in providing content, for example in making data available or providing an expert to speak/write regularly on a topic related to the interventions.

• NGO as capacity builder. NGOs may be well placed to provide technical assistance and training related to both media development and the interventions.

• NGO as content disseminator. NGOs may be well placed to re-use, disseminate or publicize media content through their own networks.

• Local government/Service Providers as content provider. In Kebumen, for example, the local regent took the initiative to establish an interactive radio program called Selamat Pagi, Bupati (Good morning, regent) in which she discussed with listeners their concerns and suggestions regarding local government

• Local government/Service Providers as content disseminator. Service providers may be well placed to re-use, disseminate or publicize media content through their own networks.

Partnership facilitation

This part of the strategy focuses on the social aspects of building the partnerships beyond the media sector necessary to enhance the media’s role in the community and ensure the broader dissemination of content. It will entail Media Intermediary Organizations undertaking the following:

• Assess the existing media landscape and assessing potential partnerships. • Arrange meetings between interested media outlets and partners.

• More broadly, organize forums and other get-togethers for decision makers in media outlets to be briefed about the benefi ts of such partnerships and to meet potential partners. • Provide follow-up support to guide such partnerships through the exploratory stages.

3. 2 Pilot Strategy

We plan to make use of the most appropriate channels—which could be a TV station or a citizen journalist’s blog, a Facebook page or a village notice board—to build the media component of our interventions. Where possible we will build on those channels that already exist and either strengthen them—through capacity building of users, maintainers and producers of content—or assist in upgrading them technologically—linking one community radio station with another, for example, or improving the technical quality of publishing, broadcast etc. Where such channels do not exist, we will seek to build them—a Facebook page for business users in Makassar, for example.

Ma kassar: Facebook

Makassar, the provincial capital of South Sulawesi, has a high number of Facebook users (383,840, or nearly 32% of the estimated district population), so we have chosen this district for a pilot in the intervention for business enabling. We believe that the combination of a strong Facebook usage and the communication-oriented business community will offer a chance to experiment with a more telecommunications-focused social-media approach. The goal will be to use Facebook’s features to build a community of end-users (or potential end-users) of the One Stop Shop business enabling service to share experiences, offer feedback and receive updates, information and responses to their queries from Service Providers themselves. This will act as an extra layer to the blanket intervention, and will, we hope, serve as a growing presence for each stage of the intervention.

In Makassar, one of our target areas, social networking tool Facebook is a very popular service— nearly 400,000 Facebook users have listed themselves as being resident of, or connected to Makassar, which makes it one of the biggest communities in the country. Although it’s not possible to break down the data further, it’s likely that many of these Facebook users are businesspeople, making Makassar a suitable candidate for our fi rst initiative to build a community atop the social network.

The goal will be to use the page as a key channel for the supply side to connect to the demand side, and to build a circle of interaction allowing users, and potential users, of the OSS service to pass feedback, to help other users, and to provide stories of their own—both positive and negative.

The longer term objectives are to learn lessons that can be applied using similar tools elsewhere, or whether there were lessons that could be applied to different, and not necessarily social-media oriented, tools.

The SPMO will build the page—itself a simple task, requiring no programming or other computer knowledge—and then add content derived from existing material (see Content Development above). Once activated, the SPMO will reach out to potential users of the page through Facebook and other channels (mentioning it in media interviews, linking to it on government webpages etc.) to build up the community. If business communities exist either online or offl ine, or even within Facebook itself, leaders of those communities can be encouraged to participate by recruiting more users and, perhaps, moderating and adding content to the page.

The SPMO will also be responsible for interacting with users on the page to pass on comments, answer questions and develop the Facebook community as a key interface between the demand and supply side. As the interventions mature and feedback and complaint handling mechanisms are introduced/expanded upon, the Facebook page can evolve into a channel for those aspects of the intervention as well.

The Facebook pilot lends itself to the particular problem of business license delivery. Users complain about a lack of transparency and information, both before submission of papers and after. There is no simple way to monitor the status of an application once it has been submitted; and it is not always clear whether authority to approve the application has been transferred to the OSS or has been retained, or recovered, by the previously responsible local offi cial or offi ce.

Facebook offers a number of advantages. For one thing, as mentioned above, it’s highly popular in Indonesia, and beyond a small urban elite. Prices of devices and data charges have dropped to the point where it’s not uncommon to fi nd blue-collar workers using the service.

Another is that Facebook is a natural information sharing and networking tool. Facebook connects individuals who are friends, but Facebook pages connects those with shared interests—be it in people, things, places, or activities. In other words, a Facebook page can serve as a way for people who may not know each other previously to connect and share over an interest they have in common. It’s a natural stakeholder forum.

Its accessibility and semi-permanence mean that it will prove useful throughout the entire process. The Facebook page, moreover, is accessible to anyone with a Facebook account, meaning that it will be fully transparent and the offi cials responsible for posting there will be clearly identifi ed, promoting “ownership” of the comments made.

is not a tool that can be used in isolation: all the content produced on it that might be useful to non-Facebook users needs to be collated and delivered elsewhere. However, as we’ve pointed out, one of the guiding principles of the media strategy is cross-disseminate content—that is, to ensure that one particular response, or article, or video, or podcast, is not used once, but repurposed and republished as far and as much as possible in order to reach as broad an audience as possible. Facebook will just be another one of these channels, but perhaps one that will yield important lessons for optimizing other channels.

We believe we will be breaking new ground in using Facebook, as there is as yet no signifi cant academic literature on its usage in such programs.

Steps:

Training. Capacity building of SP by Kinerja Media in Facebook page curation and outreach: Kinerja will train Service Providers in Makassar on how to use Facebook features (primarily the page function, which allows an individual or organization to create their own Facebook subdomain (www.facebook.com/subdomain) to interact with others and post data, photos and updates.

Research of existing communities. Service Provider Media Offi cer (SPMO) will then research existing intervention sector stakeholder presence on Facebook: in other words, they will fi nd out whether the target group—in this case, business people—had already built any such community or network on Facebook (or other services) and also collate details of those Facebook users likely to be interested in the Facebook/Kinerja initiative.

Existing stakeholder cooperation. The SPMO will then consult with any existing stakeholder presence—anyone using Facebook in a way similar to that envisaged—about the possibility of setting up a partnership in running of their existing page, or in setting up new Facebook page for the Makassar OSS. This will then be followed by drawing up a shortlist of possible administrators/contributors/moderators of page.

Content preparation. SPMO will then prepare content for page (drawing on Kinerja resources, see below), including regulations, links, related Facebook pages; as well as collecting data on local Facebook population and likely interested participants of page.

Launch. Sets up page, adds content, invites identifi ed participants to join.

Monitoring. Monitors contributions to page, engages others users, focuses on maximizing quality participation and steering discussion where relevant to the nature of the topic in question. Assigns modest budget to publicizing page on Facebook and elsewhere; ensure address of page is on all SP literature.

Training. Capacity building of local stakeholders (business association, SP, Service Units) in contributing to and curating page. The goal will be to gradually hand over running of the page to the stakeholders themselves, perhaps as a shared responsibility.

So uth Sulawesi: Community Radio Network

Community radio has an important role to play in many areas where Kinerja is working, not least because they’re the often only source of outside information. But many community radios remain somewhat isolated, unable to offer programming beyond live shows that feature speakers who are resident of the village. We hope through this pilot to offer expertise and technical support to build a mini-network of radio stations helping them to share content and thereby give their listeners access to a broader range of views on the topics covered by the intervention, as well as offering a way for them to channel their feedback to Service Providers, and, in turn, for Service Providers to respond to their concerns.

Where community radio exists as the main channel of local information dissemination we will seek partnerships to strengthen existing networks of cooperation between the radio stations, helping them to develop content, build capacity and improve the inward fl ow of upper level information (interviews with Service Providers answering listeners’ questions for example) and outward and circular fl ow of feedback (users’ experiences shared with users in other villages, and with Service Providers.)

The key element here is leveraging cheap and available technology: content will be transported between radio stations either by GPRS signal (cellphone modem) or physically. The size of the fi les will be reduced as much as possible by pre-editing content before transmission.

The process will be for each participating radio station to record their broadcast on a chosen subject, then to edit it down to, say, a 10-minute segment of highlights before transferring it to USB or transmitting it. Each station will then have 10-minute segments from each partner station that they then could collate into one show. Added to this could be a segment of a spokesperson for the Service Provider offering additional content—responses, for example, to questions and points raised in a previous program, or announcing new initiatives and changes to existing programs, or an interview. These collated shows could then be rebroadcast, and repurposed by other outlets. Kinerja’s service partners will fi rst identify target areas: existing community radio stations that are the primary, or a key, source of community information. Considerations will have to be taken for physical proximity and/or availability of GPRS/3G signals.

Create partnerships with radio station stakeholders and assess needs (capacity building, equipment), existing content/programs that will mesh well with the intervention topic(s).

Assess existing partnership or potential for partnership between community radio stations in the area, and, if partnership exists, how they work (content sharing, capacity sharing etc).

Help develop sharing mechanisms, options include:

Streaming (not necessarily practical in rural areas)

Recording content and then delivering it via USB and motorcycle taxi (ojek) or other form of transport) to a central location equidistant from all participating stations. The MP3 fi le is uploaded to a computer and the other segments of the show are downloaded.

Recording content and then delivering it via GPRS to a computer where the Service Provider/ Service Unit edits the content together into one fi le which is then ready for downloading by each station. Data upload bandwidth is usually more limited than downloading, so each radio station will be committed only to uploading a relatively small fi le, but downloading—where the bandwidth is more generous—would involve a much bigger fi le.

These shows would be a regular feature, and could be circulated more widely to non-participating stations if the interest was there. The content created could be transcribed and stored/recirculated as valuable testimony from grassroots service users.

GPRS 10 MB in 10 mins

GPR S 10

MB in 10 mins

Option 2: station-generated content is uploaded by GPRS to a central server where it is edited, content added and concatenated into one program, which is then downloaded by stations via GPRS.

SM S Gateway in Aceh and East Java

SMS gateways can be an excellent opportunity to improve accountability in public services delivery and in local governance. Several local governments have taken advantage of the high rates of cell phone usage in Indonesia and created SMS gateways to handle general service provision complaints. The use and goals of SMS gateways is highly diverse, but all share a basic principle: they enable the public to communicate complaints to service providers and make it easier for service providers to respond. SMS gateways can be even more effective when the media becomes involved in the publication of complaints and responses by service providers, thereby ensuring a more transparent process.