Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:27

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Use of Student Field-Based Consulting in Business

Education: A Comparison of American and

Australian Business Schools

Donald Sciglimpaglia & Howard R. Toole

To cite this article: Donald Sciglimpaglia & Howard R. Toole (2009) Use of Student Field-Based Consulting in Business Education: A Comparison of American and Australian Business Schools, Journal of Education for Business, 85:2, 68-77, DOI: 10.1080/08832320903253619

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320903253619

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 50

View related articles

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS, 85: 68–77, 2010 CopyrightC Heldref Publications

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832320903253619

Use of Student Field-Based Consulting in Business

Education: A Comparison of American and

Australian Business Schools

Donald Sciglimpaglia and Howard R. Toole

San Diego State University, San Diego, California, USA

This study reports the results of a comparative study of American business schools and Australian schools of commerce regarding utilization of field-based consultancy and associated critical variables. Respondents in the survey were 141 deans of Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) accredited business schools in the United States and 71 heads of Australian commerce programs. Overall, student field-based consultancy is widely used in both countries. This indicates that it should be possible to implement international field-based consultancies between American and Australian business schools, which would, in turn, lead to increased potential for international study abroad for business students of both countries.

Keywords: American business education, Australian business education, Field-based consult-ing, Management education, Service learning

Doran, Sciglimpaglia, and Toole (2001) addressed recent and pending changes in American Association to Advance Col-legiate Schools of Business (AACSB) business education. As an introduction to their study, which presented results of a survey on the role of field-based consulting (FBC) expe-riences, they noted, “As we enter a new millennium, many business disciplines are undergoing a major and pronounced period of change. Those critical of traditional academic ap-proaches have called for significant improvements to increase the relevance of what is taught and to improve the quality of graduates. Part of these challenges stem from more system-atic critiques of business education in general. In recent years, academic programs in business have come under fire for be-ing too passive, for possessbe-ing too many artificial boundaries between disciplines, and for being too teacher directed” (p. 8). Some have questioned educators as not seeing the busi-ness environment as do managers (Aistrich, Sciglimpaglia, & Saghafi, 2006). We hold that one of the pedagogical solu-tions to the challenges presently faced by business education is the increased introduction of FBC into the business cur-riculum. Many leading MBA programs such as those Duke

Correspondence should be addressed to Howard R. Toole, School of Ac-countancy, College of Business, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-8221, USA. E-mail: htoole@mail.sdsu.edu

University, the University of Chicago, and the University of Virginia, to name just a few, have instituted such programs (West & Aupperle, 1996). FBC programs are also common in Australia (Henderson, Sciglimpaglia, & Toole, 2003; Whit-tenberg, Toole, Sciglimpaglia, & Medlin, 2006). In addition, a recent review of experiential learning theory (Kolb & Kolb, 2005) suggests that FBC is firmly supported by this theory.

AACSB International accreditation standards clearly sug-gest a move toward more experiential education. Ames (2006) noted that the current standards (Association to Ad-vance Collegiate Schools of Business [AACSB] Interna-tional, 2005) advocate an increase and enhancement of ex-periential education in higher business education. We are unaware of any prior AACSB statement which takes such a strong stance. The FBC model is a typical form that is taken in business school environment, not only in the United States but internationally as well. In the 2005 standards, no di-rect mention of FBC is made. However, AACSB specifically notes the need for responsive interaction learning among stake holders, implying a pronounced need for interaction between business students and businesses or organizations. The active, reflective learning that occurs in a FBC format is ideally suited for this purpose. Ames (2006) stated, “Accord-ing to AACSB, interactive experiences must be available in all major learning experiences of the business school” (p. 2). Thus, it may be expected that methodologies such as FBC

and other responsive-interaction methodologies become in-creasingly incorporated into the curricula of AACSB schools and those aspiring to accreditation.

Other research has reported on the use and acceptance of FBC in American business schools (e.g., Doran et al., 2001). In the present study, we looked at use and applicabil-ity of FBC in an international context, comparing American and Australian education. We were interested in determining how the Australian experience with FBC compares with that in the United States. A major reason for our interest was that Australian universities are in the early stages of receiving AACSB or other accreditation and should be in a position to respond to the AACSB call for the enhancement of expe-riential learning in business education. The overall purpose of this research study was to determine the extent of pene-tration of FBC in Australia and to compare that with use of FBC in American AACSB business programs. In addition, the present study provided an opportunity to compare other pedagogical and administrative factors as well. The operat-ing premise was that the results should be similar because the Australian economy is similar in nature to that of the Amer-ican economy, and the Australian education system is quite similar and the Australian government recently sponsored a thorough reexamination of the Australian higher educa-tion system. The Australian government’s reexaminaeduca-tion of business education culminated in a policy document known as the Karpin Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 1995). which yielded many educational recommendations regarding business education which parallel the American experience. In addition, as Australian universities move toward AACSB or other international accreditation, it would seem that they would be motivated to respond to the 2005 AACSB call for enhancing experiential learning. The call for increased experiential education raises numerous difficult assessment issues. We do not address these issues in this article, but they are the subject of future research we are presently undertak-ing.

COMPARING THE UNITED STATES AND AUSTRALIA: ECONOMY AND BUSINESS

SCHOOL EDUCATION

Australia and the United States are similar along a number of economic and educational dimensions. Australia’s econ-omy is similar to that of the United States, but very much smaller, with GDP (purchasing power parity) of$666 billion compared with$13 trillion (2007) in the United States. The private sector is dominant, with what is left of the public sec-tor rapidly being privatized. Even the local post office is now a franchise operation. The population is slightly more than 20 million, the main reason for the only substantial difference with the United States. This small market is not large enough to support an efficient manufacturing sector without substan-tial exports. Similarly, the primary sector produces far more

than the population can consume so exports are critical. The Australian economy is, therefore, very dependent on exports and more vulnerable than the United States to economic con-ditions in other countries. In most other respects, however, the Australian economy is very similar to that of the United States.

Australian universities are almost exclusively federally funded and differ from their U.S. counterparts in several important respects. First, most basic undergraduate degrees (such as the BA) are done in 3 years. Credits are counted the same as in the United States, but semesters tend to be shorter than their American counterparts. The second major differ-ence is that most professional studies (e.g., medicine) start at the undergraduate level. There is nothing comparable to an American-style graduate school except in business in which the MBA is widely used to give basic business skills. Finally, a lecture–tutorial system is firmly ingrained in Australian university education.

In Australia, business or commerce programs are located in various divisions (or faculties) of the university, with no uniform administrative structure. In some cases, there is a separate business faculty and, in others, they are grouped with law or social sciences or some other disciplines. Similarly, there is no uniform title for business schools. Some are called schools, some are called departments, some are called divi-sions, some are called faculties, and some are called sections. There is no major generally accepted accreditation process for business schools apart from accreditation by the profes-sional accounting associations and there is nothing equivalent to an association of business schools. Recently, a small num-ber of schools have become accredited by the AACSB or have obtained European accreditation.

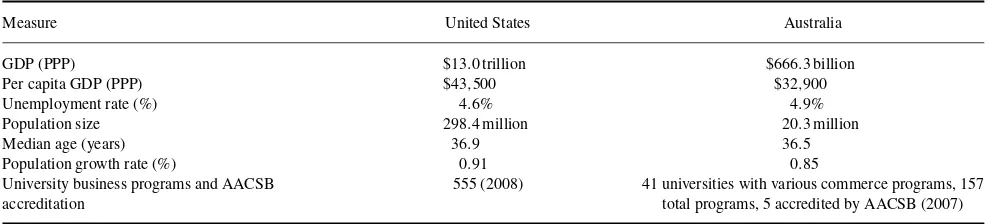

In conclusion, the subsequent exhibit summarizes a com-parison between Australia and the United States, based on data from the World Factbook (Central Intelligence Agency, 2007). With the exception of pure size of economy and pop-ulation, the two countries are very similar, with compara-ble per capita GDP, employment, population growth, and age distribution. As noted, business or commerce programs are found in a variety of academic faculties or schools in Australia. Although we identified a total of 157 separate programs (subsequently discussed), only 5 are currently ac-credited by AACSB, compared with 555 in the United States (2008). Table 1 summarizes the comparison of the United States and Australia.

AUSTRALIA’S KARPIN REPORT

In 1995, the Australian government sponsored a thorough reexamination of the education system, designed to study the country’s readiness to compete in a world economy. The resulting study, known as the Karpin Report, ad-dressed a number of key issues regarding Australian business

70 D. SCIGLIMPAGLIA AND H. R. TOOLE

TABLE 1

Selected Characteristics of the United States and Australia

Measure United States Australia

GDP (PPP) $13.0 trillion $666.3 billion

Per capita GDP (PPP) $43,500 $32,900

Unemployment rate (%) 4.6% 4.9%

Population size 298.4 million 20.3 million

Median age (years) 36.9 36.5

Population growth rate (%) 0.91 0.85

University business programs and AACSB accreditation

555 (2008) 41 universities with various commerce programs, 157 total programs, 5 accredited by AACSB (2007)

Note.PPP=purchasing power parity; AACSB=Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business.

education and has become a widely cited source on business and commerce education. That report argued that

the over-emphasis on functional skills and the competitive ethos of many functional specialist schools in universities and other educational institutions act as a barrier to build-ing better teamwork skills and an integrated approach to business management. Despite considerable investment in management education, the universities are not adequately addressing the issues related to cross-functional integration for educating graduates. . .(Seethamraju, 1999, p. 133).

Another recent study indicated that “Academics have favourable attitudes to small business and entrepreneurship education and strongly support the Karpin recommenda-tions” (Breen & Bergin, 1999, p. 2). Those recommen-dations were, in part, summarized by King (1997), who stated,

‘Education for and through enterprise’ was the refrain of the 1995 Karpin report to the federal Labor government, attempting to legitimize direct ties between the school sys-tem and business. Since that time, the trend towards tying school education to the needs of business has increased rapidly.

One of the major recommendations of the Karpin Report is that MBA students (and, it follows, for undergraduates as well) should consult with businesses (Anderson, 2002). This recommendation parallels the use of FBC as a teach-ing methodology in the United States. This methodology, if widely employed, may be seen as one that helps increase the cross-functional integration of business students and achieve one of the goals of the Karpin Report.

However, prior to the publication of a recent study by Henderson et al. (2003), based on a survey of Australian busi-ness educators, there was little understanding of the extent to which FBC had penetrated Australian business education. In fact, Breen and Bergin (1999) summarized the state of knowl-edge as, “It appears that little research has been undertaken in Australia in the years following the 1995 Karpin Report so it is difficult to ascertain the effect, if any, on the extent

and type of teaching of small business and entrepreneurship education taking place in Australian universities” (p. 11).

FIELD-BASED CONSULTING

We use the termfield-based consultancy(FBC) through out this paper. FBC is a methodology which employs a live-case approach by utilizing students or student teams to consult with actual clients in the business community. By experienc-ing the consultation process, students are required to inte-grate all they have learned in their prior education to bring relevant tools to their consultancy engagement. The course is frequently structured along the lines of a consulting firm. A more complete discussion of the FBC framework may be found in Kunkel (2002).

THE STUDY

In this article, we present results of research designed to explore some of the critical variables associated with FBC as an aid to designing successful FBC programs in American and Australian business schools. The major objectives of the study were to determine:

1. Extent of utilization of FBC in American and Aus-tralian business programs,

2. Alternative ways of structuring FBC experiences in business curricula,

3. Alternative methods of measuring student performance employed in FBC experiences, and

4. Key success factors for the FBC experience.

The research was designed to explore the critical vari-ables associated with FBC experiences in American and Australian business schools. In the United States, all 594 deans of AACSB member business schools were identified and surveyed by mail survey to ascertain the extent of in-volvement with FBC and the associated success factors. The

overwhelming majority (now 555) of the 594 member schools are accredited. A second mailing was sent approx-imately 2 weeks later. Deans (or their designees) returned a total of 141 questionnaires, a response rate of 24% of all AACSB member business schools in the United States.

Because no counterpart to AACSB exists in Australia, a large-scale Internet study of university Web sites was used to identify Australian commerce programs. Using this method, a total of 41 Australian universities with commerce pro-grams were identified. From these Web sites, administra-tive personnel with similar organizational responsibilities to American business school deans were identified, yielding to-tal of 157 heads of the various commerce programs. Each administrator was sent a questionnaire by mail, with a sec-ond mailing approximately 2 weeks later. By the close of the study, a total of 71 heads of Australian commerce pro-grams had responded, a response rate of 45%, nearly double of that in the United States. The survey questionnaire was adapted from a study reported by Doran et al. (2001). Their study addressed the importance of a number of dimensions of field based consulting, as viewed by deans and adminis-trators in American business school programs. It evaluated perceived advantages and disadvantages of FBC, alternative forms of implementation, grading policies, faculty-related issues, and key success factors. For the present study, the American questionnaire version was used with little modi-fication. The Australian version was designed, as much as possible, to parallel that of the American survey. Many of the constructs and program elements are directly comparable, but some subtle differences exist. For example, as noted, Aus-tralian business-school programs are 3 years in length, most business or commerce programs can be housed in a variety of academic faculties, many principal administrators may be involved and distance learning is common. By comparison, most American business-school programs are 4 years long, have a typical unified department or school, have one chief administrator, and place much less emphasis on distance ed-ucation. Therefore, the resultant questionnaire was reviewed by six Australian business faculty to see what changes were necessary for implementation in that country. As a result, a few minor terminology changes were made. The Australian version of the questionnaire is shown in the Appendix.

RESULTS

The results show that, overall, in the United States and Aus-tralia, a total of 54.5% of the responding business programs reported using FBC at either the undergraduate or graduate level. In total, 80 colleges or universities in the U.S. sam-ple and 25 in the Australian samsam-ple offered some form of FBC program. This was significantly higher among business schools (65.4%) in the United States than those in Australia (35.5%), as shown in Table 2. Responses from these 105

col-TABLE 2

Percentage of Student Field-Based Consulting in Business Programs

leges and universities in both countries became the basis of the experience survey reported in this article.

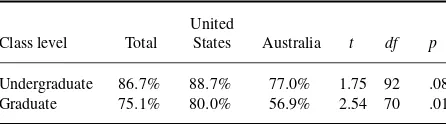

We attempted to determine to what extent FBC is used by the business schools in our sample. These findings are shown in Table 3. Overall, FBC was utilized in 86.7% of undergradu-ate programs and 75.1% of graduundergradu-ate programs. Table 3 shows that we may conclude that the degree of penetration of FBC is greater in the United States than in Australia. There is not a significant difference at the undergraduate level, in which 88.7% of the U.S. respondents and 77.0% of the Australian respondents reported some form of FBC in use, but there is a significant difference at the graduate level in which 80.0% of U.S. respondents and 56.9% of the Australian respondents re-ported some form of FBC in use. A number of reasons may be hypothesized for these differences. First, American schools and colleges of business tend to practice more outreach activ-ities than their Australian counterparts. Thus, a community of interest is established and the American schools rely on this for financial and other forms of support. In contrast, the Australian universities do not seem to have developed such a tradition and rely almost exclusively on the national govern-ment and student fees for support. A second possible reason is that Australians tend to go to the university straight from secondary school and, thus, are younger and less experienced than their American counterparts. Finally, Australian univer-sities are still typically very academic and much emphasis is placed on formal examinations. The AACSB call for ex-periential learning may change this in the long run. At the undergraduate level 3-hr examinations in each subject are the norm.

Another area of inquiry was to determine the level of in-tensity of use of FBC methodology. These results are shown

TABLE 3

Proportion of Business Students Involved in Field-Based Consulting

Class level Total

United

States Australia t df p

Undergraduate 86.7% 88.7% 77.0% 1.75 92 .08

Graduate 75.1% 80.0% 56.9% 2.54 70 .01

72 D. SCIGLIMPAGLIA AND H. R. TOOLE

TABLE 4

Percentage of Student Workload Made Up by Field-Based Consulting Courses

Class level Total United States Australia

Undergraduate

in Table 4. As shown, overall more than one half of the schools in the sample used FBC for one quarter or more of their course. Table 4 also shows that the intensity of the FBC experience was greater in the United States than in Australia for undergraduate coursework. In Australia, when FBC is used as a methodology, about two thirds of the time it usually represents only 25% or less of the proportion of student workload in an FBC course. By way of contrast, in the United States only about one third of the time FBC represented 25% or less of the proportion of student work-load. The lack of a relationship with the business commu-nity and student age might again be hypothesized as the cause of these findings. These differences were found to be significant.

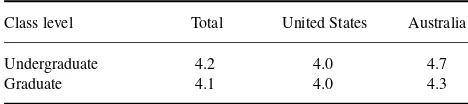

We tried to determine the composition of FBC courses in the United States and in Australia. Table 5 shows that Australian universities tend to favor a somewhat larger size for the FBC teams than do their American counterparts. The average size for graduate and undergraduate FBC teams in the United States was 4.0 students. In Australia, the average size for undergraduate FBC consulting teams was 4.7, which was significantly greater than in the United States. The average in Australia at the graduate level was greater (4.3), but not significantly different than that in the United States. This is not a surprising finding. If there is less interaction in Australia

TABLE 5

Average Team Size of Student Field-Based Consulting Assignment

Class level Total United States Australia

Undergraduate 4.2 4.0 4.7

Graduate 4.1 4.0 4.3

Note.Undergraduatet(90)=1.41,p≤.16; graduatet(77)=0.50,p≤ 0.62.

TABLE 6

Percentage of Schools With Graduation Requirement for Field-Based Research

Class level Total United States Australia

Undergraduate

Note.All percentages add to 100. Undergraduateχ2(1,N=97)=

0.27,p≤.76; graduateχ2(1,N=98)=3.59,p≤.17.

between the universities and the business community, then there are relatively fewer businesses available and, hence, the teams need to be larger.

We were interested to determine to what extent business schools required FBC experience as a graduation require-ment. As Table 6 shows, there was no FBC requirement for graduation in the vast majority of Australian and American universities. In both Australia and the United States, the per-centage of schools requiring a FBC experience was greater in graduate programs than in undergraduate programs, and higher in the United States than in Australia. Overall, 17.3% of schools required a FBC experience for undergraduates. This number was higher for graduates, at 22.2%. The Ameri-can and Australian business programs were not signifiAmeri-cantly different at either level.

One of the major purposes of the research was to assess student, administrative, and client factors that affect the suc-cess of FBC projects. No express definition of sucsuc-cess was given, as this was a subjective evaluation of the respondents. Student factors were first examined. A 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very adverse) to 5 (very positive) was used to measure the impact of class size, type of student, and assignment type. Table 7 shows that overall success was very sensitive to class size. United States and Australian respondents felt a class size of less than 20 is optimal. In-terestingly, American respondents generally favored smaller class sizes, significantly different than their Australian coun-terparts. Part-time student status is seen as negatively im-pacting success, with no significant difference between Aus-tralian and American results. Team consulting was favored over individual consulting. Interestingly, American respon-dents rated team consulting as a significantly more positive impact than their Australian counterparts (4.4 vs. 4.0). The results are shown in Table 7.

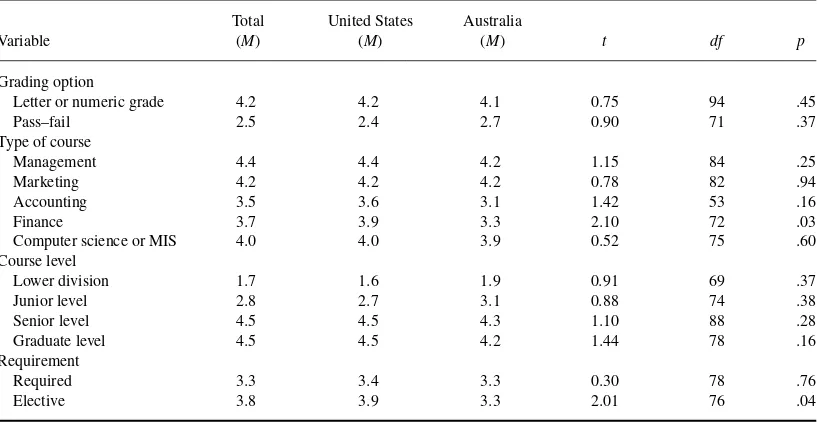

Administrative factors were next examined. A 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very adverse) to 5 (very positive) was used to measure the impact of grading systems, type of course, course level, and required or elective course status. Letter or numeric grading systems were strongly fa-vored over pass–fail grading systems with virtually identical

TABLE 7

Student Factors Influencing Success of Field-based Consulting Experiences

Total United States Australia

Variable (M) (M) (M) t df p

Class size

Under 20 4.2 4.3 3.8 2.20 106 .03

20–40 2.9 2.8 3.3 1.84 93 .07

41–60 1.9 1.7 2.7 3.60 94 .00

Over 60 1.7 1.5 2.3 3.20 93 .00

Students

Part time 2.7 2.7 2.9 0.84 103 .40

Full time 3.9 3.9 3.8 0.48 98 .63

Type of consulting

Individual 2.9 2.8 3.0 0.50 90 .63

Team 4.3 4.4 4.0 2.40 97 .02

results for Australia and the United States. FBC is seen as applicable across the curriculum but more likely to lead to a successful consulting outcome if offered in manage-ment and marketing courses. Computer science–information systems, finance, and accounting were rated lower. There were no significant differences on this dimension between Australian and U.S. responses. FBC was judged to be ap-propriate for elective or required courses, with use in elec-tive courses favored. Generally there were no differences between the two sets of respondents on these questions, with one exception: American respondents showed a signif-icantly greater preference for an elective course format than did their Australian counterparts. The results are shown in Table 8.

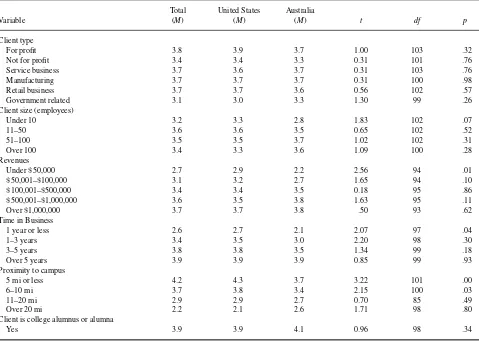

Client-related factors were the last area investigated. A 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very adverse) to 5

(very positive) was used to measure the impact of client type, size, revenues, time in business, proximity to campus, and alumni status. In general, business schools found the most ap-propriate use of FBC is with for-profit firms, firms with more than 10 employees, firms with over$100,000 in revenues, firms that had been in business 3 years or more and firms in which the owner or manager was an alumnus or alumna of the university offering the consulting services. In most cases there were no significant differences between the responses of the U.S. and Australian samples (Table 9). American busi-ness programs felt that client revenues under$50,000 was a

significantly more appropriate to FBC success than were their Australian counterparts. This is interesting, given the nature of the Australian economy, with many small businesses, but is consistent with the historic SBI type mission in the United States.

TABLE 8

Administrative Factors Influencing Success of Field-Based Consulting Experiences

Total United States Australia

Variable (M) (M) (M) t df p

Grading option

Letter or numeric grade 4.2 4.2 4.1 0.75 94 .45

Pass–fail 2.5 2.4 2.7 0.90 71 .37

Type of course

Management 4.4 4.4 4.2 1.15 84 .25

Marketing 4.2 4.2 4.2 0.78 82 .94

Accounting 3.5 3.6 3.1 1.42 53 .16

Finance 3.7 3.9 3.3 2.10 72 .03

Computer science or MIS 4.0 4.0 3.9 0.52 75 .60

Course level

Lower division 1.7 1.6 1.9 0.91 69 .37

Junior level 2.8 2.7 3.1 0.88 74 .38

Senior level 4.5 4.5 4.3 1.10 88 .28

Graduate level 4.5 4.5 4.2 1.44 78 .16

Requirement

Required 3.3 3.4 3.3 0.30 78 .76

Elective 3.8 3.9 3.3 2.01 76 .04

Note.MIS=Information Systems.

74 D. SCIGLIMPAGLIA AND H. R. TOOLE

TABLE 9

Field-Based Client-Success Factors

Total United States Australia

Variable (M) (M) (M) t df p

Client type

For profit 3.8 3.9 3.7 1.00 103 .32

Not for profit 3.4 3.4 3.3 0.31 101 .76

Service business 3.7 3.6 3.7 0.31 103 .76

Manufacturing 3.7 3.7 3.7 0.31 100 .98

Retail business 3.7 3.7 3.6 0.56 102 .57

Government related 3.1 3.0 3.3 1.30 99 .26

Client size (employees)

Under 10 3.2 3.3 2.8 1.83 102 .07

11–50 3.6 3.6 3.5 0.65 102 .52

51–100 3.5 3.5 3.7 1.02 102 .31

Over 100 3.4 3.3 3.6 1.09 100 .28

Revenues

Under$50,000 2.7 2.9 2.2 2.56 94 .01

$50,001–$100,000 3.1 3.2 2.7 1.65 94 .10

$100,001–$500,000 3.4 3.4 3.5 0.18 95 .86

$500,001–$1,000,000 3.6 3.5 3.8 1.63 95 .11

Over$1,000,000 3.7 3.7 3.8 .50 93 .62

Time in Business

1 year or less 2.6 2.7 2.1 2.07 97 .04

1–3 years 3.4 3.5 3.0 2.20 98 .30

3–5 years 3.8 3.8 3.5 1.34 99 .18

Over 5 years 3.9 3.9 3.9 0.85 99 .93

Proximity to campus

5 mi or less 4.2 4.3 3.7 3.22 101 .00

6–10 mi 3.7 3.8 3.4 2.15 100 .03

11–20 mi 2.9 2.9 2.7 0.70 85 .49

Over 20 mi 2.2 2.1 2.6 1.71 98 .80

Client is college alumnus or alumna

Yes 3.9 3.9 4.1 0.96 98 .34

CONCLUSIONS

Analyses of the responses to these surveys indicate a similar penetration of field-based methodology in Australia com-pared with that in the United States (see Doran et al., 2001). The Karpin Report called for the need for more cross-functional and integrative programs in Australian commerce education, and the Karpin report is seen to be consistent with the 2005 AACSB standards. Results from the present study suggest that, parallel to American business education, uni-versities in Australia do have extensive field consulting pro-grams. These often take the form of teams of students who work with small business clients on a wide variety of man-agerial issues. Positive attitudes among Australian business faculty toward small business and entrepreneurship clearly further support the utilization of FBC in commerce educa-tion. In the United States and in Australia, FBC methodology is being employed as an appropriate form of business educa-tion. Over one half of the respondents to both surveys indicate the use of FBC methodology in their curriculum. Given the similarity of the survey responses, the Australian higher ed-ucation system, the Australian economy, and the lack of a

major language barrier between the two countries, the results lead to the possibility of implementing international FBCs between American and Australian business schools, albeit, affordability is a question. This leads to increased potential for international study abroad for business students, given similarity of cultures and commonality of language. As ev-idence, Carnegie Mellon University recently announced a program with the state of South Australia as example of this course of action. In addition, it would seem that Aus-tralian universities should not find that a lack of experiential learning is impediment to future AACSB accreditation. The Australian experience generally seems to mirror that of the United States.

The findings from the present study validate some basic underpinnings of business-education curriculum and design. Student-based factors perceived as influencing success in-cluded smaller classes, usually at a senior or graduate level of study, graded coursework as opposed to pass–fail, and full-time students. Respondents believed that established, for-profit businesses were likely to be the most successful FBC clients. Lastly, a client business within a 4-mile radius of campus was also viewed as adding to the success of the

project. The respondents rated the number of employees and the annual revenues evenly, with no one category viewed as more or less successful.

As a learning method, field-based learning adds value to students, the clients involved, the faculty, and the institutions. The hurdles continue to be the need for a fair allocation of the time and resources to the parties involved. Once the value added by FBC programs to the students, clients, faculty, and institution are clearly understood, it should be easier for college administrations to fairly support faculty involvement in programs such as the Small Business Institute in the United States as well as other similar programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the faculty of the College of Business Ad-ministration at San Diego State University and the College of Commerce at Adelaide University for help with previous versions of this manuscript and the survey instrument. In ad-dition the authors would like to thank the anonymous review-ers of the Journal of Education for Business for numerous helpful comments which have improved this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Aistrich, M., Sciglimpaglia, D., & Saghafi, M. (2006). Ivory tower or real world: Do educators and practitioners see the same world?Marketing Education Review,16(Fall), 73–80.

Ames, M. D. (2006, January). AACSB International’s advocacy of ex-perimental learning and assurance of learning—Boom or bust for SBI student consulting? The changing entrepreneurial landscape. Proceed-ings of the USABE/SBI 2006 Joint Conference, Tucson, Arizona, USA, 8–15.

Anderson, J. (2002, September).Opening plenary session speech. Small En-terprise Association of Australia and New Zealand Conference, Adelaide, Australia.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International. (2005).Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accreditation(Rev. ed.). Tampa, FL: Author.

Barnett, A., Henderson, S., Sciglimpaglia, D., & Toole, H. (2002, Septem-ber). Demographics of field-based business consulting practices in Aus-tralian university commerce education.Proceedings of the Annual Con-ference of the Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand (SEAANZ), Adelaide, Australia.

Breen, J., & Bergin, S. (1999, May). An examination of small business and entrepreneurship education in Australian universities.Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne, Australia, 17–29.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2007). World factbook. Langley, VA: Author. Retrieved May 1, 2007, from https://www.cia.gov/ library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html

Commonwealth of Australia. (1995). Enterprising nation: Renewing Aus-tralia’s managers to meet the challenges of the Asia-Pacific century. Can-berra, Australia: International Best Practice in Leadership and Manage-ment DevelopManage-ment.

Doran, M., Sciglimpaglia, D., & Toole, H. (2001). The role of field-based business consulting experiences in AACSB business education: An ex-ploratory survey and study.Journal of Small Business Strategy,12(1), 8–18.

Henderson, S., Sciglimpaglia, D., & Toole, H. (2003). Field-based business consulting practice in Australian university commerce education.Small Enterprise Research,11(1), 71–82.

King, S. (1997). Schools that serve business. Green Left Weekly, 266. Retrieved December 15, 2004, from http://www.greenleft. org.au/back/1997/266/266p9.htm

Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhanc-ing experiential learnEnhanc-ing in higher education.Academy of Management Learning & Education,4(2), 193–213.

Kunkel, S. (2002). Consultant learning: A model for student-directed learn-ing in management education.Journal of Management Education,26, 121–138.

Seethamraju, R. (1999, July). ERP and business management education—New directions for education and research. Proceedings of the Third SAP Asia-Pacific Forum for Higher Learning Institutes, Singapore.

West, C., & Aupperle, K. (1996). Reconfiguring the business school: A normative approach.Journal of Education for Business,72(1), 37–41. Whittenburg, G., Toole, H., Sciglimpaglia, D., & Medlin, C. (2006). AACSB

international accreditation: An Australian perspective.The Journal of Academic Administration in Higher Education,2(1–2), 9–13.

APPENDIX

Survey Questionnaire (Australian Version)

1. Does your school, department, or discipline offer any courses in which students engage in field-based consulting?

(field-based consulting is defined as the use of students, individually or in teams, to consult with actual businesses, excluding internships) YES NO

(IF FIELD-BASED CONSULTATION IS NOT USED PLEASE DO NOT PROCEED, GO TO QUESTION #11 AND RETURN QUESTIONNAIRE)

2. What percentage of your school, department, or discipline undergraduate total class offerings utilize field-based consultation?

What percentage of your school, department or discipline graduate total class offerings utilize field-based consultation?

0%

76 D. SCIGLIMPAGLIA AND H. R. TOOLE

3. Of the undergraduate courses that utilize some form of field-based consultation, on average, what percentage of the student’s workload is field-based consultative experience?

1−25%

26−50%

51−75%

76−100%

Of the graduate courses that utilize some form of field-based consultation, on average, what percentage of the student’s workload is field-based consultative experience?

1−25%

26−50%

51−75%

76−100%

4. When undergraduate students engage in field-based consultation, what percentage work in teams? %

If teams are used, what is the typical average number of undergraduate students per team? students per team

5. When graduate students engage in field-based consultation, what percentage work in teams? %

If teams are used, what is the typical average number of graduate students per team? students per team

6. Are individual students on a team given the same grade? YES NO Don’t Know

7. Do you feel this methodology is appropriate for part-time or adjunct staff? YES NO Don’t Know

8. Is there a requirement that an undergraduate student in your program be exposed to a field-based consultative experience in order to graduate?

YES NO Don’t Know

Is there a requirement that a graduate student in your program be exposed to a field-based consultative experience in order to graduate? YES NO Don’t Know

9. Please rate the following factors in regards to their effect on the success of field-based consultative courses.

Adversely affects Does not affect Positively affects the course the course the course

Having: less than 20 students in the course

20–40 students in the course

41–60 students in the course

over 61 students in the course

Having: part time students

full time students

Consulting by: individuals

teams

Offered as: part of a management course

part of a marketing course

part of an accounting course

part of a finance course

part of a computer/MIS course

Offered as: a 1st-year course

a 2nd-year course

a 3rd-year course

a graduate level course

Grading is: a numerical score

a pass/fail grade

Is a(n): mandatory part of curriculum

elective course

Other, please specify:

10. Please rate the following characteristics of businesses in regards to their effect on the success of field-based consulting.

Adversely affects Does not affect Positively affects the course the course the course

Is a: for-profit business

nonprofit business

Is a: service business

retail business

manufacturing business

government-related business

Has been in business: less than 1 year

1 to less than 3 years

3 to less than 5 years

over 5 years

Employs: under 10 employees

11–50 employees

51–100 employees

over 100 employees

Earns revenues of: under$50,000

$50,001–$100,000

$100,001–$500,000

$500,001–$1,000,000

over$1,000,000

Proximity to university is: under 5 miles

6–10 miles

11–20 miles

over 20 miles

Business’s owner/contact is a school alumni

Other, please specify:

11. What is the title of your position?

University name:

Administrative unit for which you are responding?

Approximate number of undergraduate full time equivalent students for which you are responding?

Approximate number of graduate full time equivalent students for which you are responding? 12. Please identify the type of school: Public Private

If other, please specify:

13. Please identify the programs offered: Bachelor’s Masters M.B.A. Other If other, please specify:

14. How would you characterize the university’s surrounding community: Suburban Rural Urban Other If other, please specify: