Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Critical Look at the Use of Group Projects as a

Pedagogical Tool

Mohammad Ashraf

To cite this article: Mohammad Ashraf (2004) A Critical Look at the Use of Group Projects as a Pedagogical Tool, Journal of Education for Business, 79:4, 213-216, DOI: 10.3200/ JOEB.79.4.213-216

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.79.4.213-216

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 105

View related articles

any researchers have suggested that passive instruction through lecture is not an effective teaching mode (Bartlett 1995a, 1995b; Batra, Walvoord, & Krishnan, 1997; Bowen, Clark, Hol-loway, & Wheelwright, 1994; Comer, 1995; Goodsell, Maher, & Tinto, 1992; Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 1991; Kerr, 1983; McCorkle, Diriker, & Alexander, 1992; McKinney & Graham-Buxton, 1993; Moore, 1998; Rau & Heyl, 1990; Strong & Anderson, 1990; Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991). However, pro-fessors of economics courses often pre-fer it and chalk board techniques (Ben-zing & Christ, 1997; Becker & Watts, 2001).

As the substantial benefits of team-work to the firm became known, employers expected and witnessed an increased emphasis on group-based class projects by schools. In a recent study, Hamilton, Nickerson, and Owan (2003) found that the introduction of teams at a garment plant increased average productivity by 14%. Educa-tors try to instill the value of teamwork in students by using group-based class projects. In this study, I sought to inves-tigate whether a classroom setting is conducive to learning how to be a team player. I used a game theoretic approach to support the argument that a classroom setting is different from the real world.

A major difference between the class-room and workplace is that students in a classroom play a finite number of games with the number of games known. In a work environment, howev-er, workers play a finite number of games with the number of games unknown. As such, a classroom setting is not necessarily conducive to learning how to be a team player.

There are six different group situa-tions presented in this article. These sce-narios demonstrate that “less motivat-ed” students receive better grades at the cost of lower grades for “industrious” students.

Various teaching and learning bene-fits of group projects have been dis-cussed in the business pedagogical liter-ature. Some of the benefits that

reportedly have accrued to students include cooperative and peer learning, peer modeling, teamwork, and efficien-cy. The benefits that presumably accrue to professors, according to the literature, include fewer papers to grade and the freedom to assign more comprehensive projects.

On the other hand, the literature indi-cates several disadvantages resulting from the practice of assigning group projects in a classroom setting: the pos-sibility of free riding; high transaction costs—especially if students are com-muting from different places or have inflexible schedules because of other obligations (e.g., family, work); poor product quality; stifled individual cre-ativity resulting from within-group dynamics; and poorly structured projects, which may result in delays.

Researchers have also argued that group projects serve as latent barriers to learning new skills. Because students tend to divide the workload of a large project, with each student picking the task that he or she has done in some other project, they do not learn any new skills. This situation leads to the absence of broader knowledge.

This brief review of the existing liter-ature does not provide enough evidence for or against the use of groups and group projects as pedagogical tools. Furthermore, the existing literature is

A Critical Look at the Use of Group

Projects as a Pedagogical Tool

MOHAMMAD ASHRAF

The University of North Carolina at Pembroke Pembroke, North Carolina

M

ABSTRACT. In business schools across the United States, one of the most common pedagogical tools is the use of groups and group projects. “Passive” instruction (i.e., lecture only) is considered to be an inferior mode of teaching. In this article, the author suggests that the use of group-based projects as pedagogical tools should be reconsidered. Although the problem of free riding in group projects in the real work environment may be mitigated by other factors, free riding in a classroom can result in higher grades for the relatively less motivated students at the cost of lower grades for industrious students.

primarily anecdotal and based on per-sonal opinion. The studies rely on sur-vey data and lack rigor in collection and data analysis. These concerns warrant the use of a theoretical point of view in the interrogation of the use of groups and group projects as pedagogical tools. The debate is not over the importance of teamwork. It is an established fact that employers seek a team player when making hiring decisions. The question is whether a classroom setting is appro-priate for acquiring such skills. Does the use of groups and group projects as ped-agogical tools pay off, or does it train “less motivated” students to become proficient free riders at the cost of lower grades for “industrious” students?

Theoretical Models

I present six models with the follow-ing basic assumptions:

1. There are two major types of stu-dents: industrious and less motivated. These categories are based on students’ grade point average (GPA) and their aptitude regarding work. That is, a stu-dent is industrious if he or she has a high GPA and wants to work. On the other hand, a student is considered less motivated if he or she does not want to work, has a low GPA, or both. The choice between working and not work-ing depends on the stakes. The higher the stakes a student has, the harder the student will work. An underlying assumption is that industrious students always have higher stakes than less motivated students. Thus, an industrious student always works at least as hard as a less motivated student.

2. The models assume that there are benefits and costs associated with obtaining good grades. The benefits of good grades are obvious (e.g., better job opportunities, happier parents, self-satisfaction). However, costs can be divided into two categories:

(a) costs associated purely with work required for the projects, or w. These costs include researching the project, learning new techniques for analysis, and putting the project together.

(b) costs associated with pulling the weight of other student(s), or c. These

costs include trying to arrange meet-ings with the rest of the group bers, persuading other group mem-bers to move in a certain direction, and explaining concepts to the rest of the group members.

Formally speaking,Piis the net pay-off to student i,biis the benefit from a good grade to student i,wiis the amount of work put in by student i, and ciis the cost associated with pulling the weight of the other student (for i= industrious, less motivated). The net payoff to stu-dent imay be written as Pi= bi– wi– ci. Because wIndustrious ≥ wLess Motivated,

cIndustrious > 0, and cLess Motivated = 0, this implies that PLess Motivated > PIndustrious. That is, less motivated students’ net payoffs are always greater than those for industrious students, and industrious students bear the cost.

3. Grades are awarded at the end of the project and are based on the finished project, not effort. The grading scale consists of A, B, C, and F (except in the cases of Models 5 and 6, where the choices are A and F), where A is the highest and F is the lowest. Further-more, A > B >C > F for both industrious and less motivated students.

4. Groups may be formed in three ways:

(a) industrious student with industri-ous student,

(b) less motivated student with less motivated student, and

(c) industrious student with less motivated student.

Furthermore, partners may be assigned by the professors, and the assignment may be random or deliberate. Alterna-tively, students may pick their own partners.

These four assumptions are true for all models presented in this article.

However, each model has its own set of additional assumptions.

Instructional Model 1 assumes the following:

(a) only one project;

(b) two players, industrious student and less motivated student;

(c) perfect and complete informa-tion; and

(d) no monitoring; that is, the profes-sor does not know which student did how much work. There are no penal-ties for shirking, and both students receive the same grade.

In Table 1, I present the payoffs matrix for Model 1. In the payoffs matrix, the first letter is the payoff of the row player and the second letter is the payoff of the column player (i.e., the less motivated student and the industri-ous student, respectively). The matrix presents four possible situations:

(a) neither the industrious student nor the less motivated student works (grades are F, F);

(b) the less motivated student works, but the industrious student does not (grades are B, B);

(c) the industrious student works, but the less motivated student does not (grades are B, B); and

(d) both students work (grades are A, A).

Because by assumption the industri-ous student always works and the less motivated one does not, this rules out situations (a), (b), and (d). The only pos-sible outcome is presented by situation (c), in which the industrious student works and the less motivated student does not. Both students receive Bs. Note that situation (d) carries a payoff of grade A for both students. If both stu-dents work and neither has to carry the other’s weight, the quality of work increases. However, because the less

TABLE 1. Instructional Model 1: Payoffs Matrix

Industrious student

Does not work Works

Less motivated student

Does not work F, F B, B

Works B, B A, A

motivated student is a free rider and the industrious student has to carry the weight of the former, the overall grade suffers.

Note also that the grade of the indus-trious student may decrease from A to B for two reasons:

1. Having to carry the weight of the less motivated student requires extra effort on the part of the industrious stu-dent. The effort expended on pulling the less motivated student along could be directed toward the project, leading to a higher grade.

2. The grade is assigned to the fin-ished project, and because the professor has no way of monitoring, there are no rewards for extra effort or penalties for shirking.

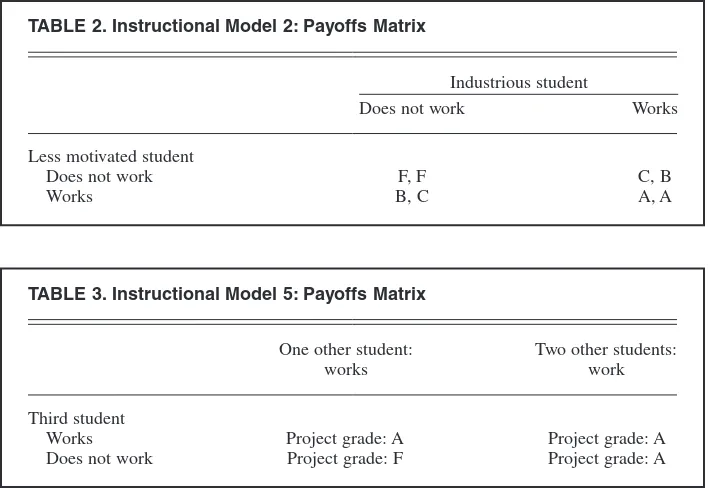

Instructional Model 2 carries the first three assumptions of Model 1. The fourth assumption of no monitoring is replaced with monitoring, and it is assumed that shirking is penalized by lowering the grade of the shirker.

In Table 2, I present the payoffs matrix. Again, the only feasible out-come is presented in the upper right-hand corner. However, notice that the industrious student still suffers in terms of grade. He or she could have earned an A instead of a B if he or she did not have to pull the less motivated student along. In other words, just penalizing the less motivated student is not enough.

There must be a reward for the industri-ous student in this situation to prevent his or her being short-changed.

Instructional Model 3 (payoffs matrix not presented) permits the students to pick their own partners. Along with the assumptions of one project and two stu-dents, the industrious student and the less motivated one, it also assumes per-fect but (two-sided) incomplete informa-tion. That is, each player knows the other player’s actions before making his or her own move. However, each player is not aware of the other player’s payoffs.

Notice that under the assumption that the amount of effort put into the project is a function of the level of stake (Assumption 1), and if each student knows what he or she has at stake for him- or herself, the knowledge about the payoffs of the other student becomes irrelevant. The industrious student always works, and the less motivated one never does. The presence of incom-plete information and the ability to pick one’s own partner do not change the results, and the less motivated student still receives higher grades at the expense of lower grades for the industri-ous student.

Instructional Model 4 (payoffs matrix not presented) relaxes the assumption of having only one project but maintains the assumption of the same two students in a group. Players are expected to play finite repeated games with the number

of games known. Model 4 also assumes that each student has the chance to have the same partner in other class projects (or classes).

Would the knowledge that one could partner with the same student in later class projects change the way one stu-dent behaves in earlier class projects? “Backward induction” dictates that as long as the number of games is known, each player behaves as if it were a one-shot game. In our case, the implication is that as long as the number of projects is known, the multiplicity of projects does not affect our outcome: The indus-trious student always works, and the less motivated one does not.

Instructional Model 5 (payoffs matrix presented in Table 3) relaxes the assumption of only two students in a group. It assumes that there are three students and that at least two are required to work to obtain a goodgrade. For ease of exposition, we maintain the assumptions of one project and no mon-itoring and further assume that (a) grades are A and F, and (b) the students have complete and imperfect informa-tion. That is, each student knows the other students’ payoffs but does not know the other students’ moves before he or she makes a move. As such, each student assigns a subjective probability θ, (0 < θ < 1) to any other student’s propensity to working.

The third student’s decision to work or not to work plays the crucial role in the overall project grade. If the third stu-dent thinks, according to θ, that the other two students will work, his or her preferred strategy would be to not work. On the other hand, if the third student thinks, according to θ, that only one other student will work, his or her deci-sion to work or not to work will depend on how badly he or she wants to avoid an F. That is, if the third student is industrious and thinks that only one other student will work, he or she will decide to work and the project grade will be an A (top-left corner). On the other hand, if the third student is less motivated, he or she will decide not to work, regardless of the decision(s) of the other student(s).

Instructional Model 6 maintains the assumptions of Model 5 except that it has N > 3 students in a group, and at TABLE 2. Instructional Model 2: Payoffs Matrix

Industrious student

Does not work Works

Less motivated student

Does not work F, F C, B

Works B, C A, A

TABLE 3. Instructional Model 5: Payoffs Matrix

One other student: Two other students:

works work

Third student

Works Project grade: A Project grade: A Does not work Project grade: F Project grade: A

least kstudents have to work to obtain a

good grade, where Nis the number of students and k> N – k.

I present the payoffs matrix in Table 4. In this model, the decision of the ith student to work or not to work plays the crucial role. If the ith student thinks, based on θ, that k other students will work or that k – 2other students will not work, his or her preferred strategy would be to not work, regardless of whether the ith student is industrious or less motivated. The project grades will be A right corner) and F (lower-left corner), respectively. In the event that k – 1other students work (middle column), the preferred strategy of the

ith student depends on his or her prefer-ences for an A as opposed to an F—that is, on whether that student is industrious or less motivated.

Therefore, group projects allow stu-dents who do not work to take advan-tage of students who do work, most often at the expense of lower grades for students who work. In infinitely repeated games or games with an unknown number of repetitions, the outcome may be different. In these cases, backward induction does not apply, which affects the future strate-gies of players (students in our case) who do not work. The infinitely repeat-ed games (or games with finite tions with unknown number of repeti-tions) scenario resembles the real workplace. However, a classroom set-ting does not allow for infinitely repeated games. Not only does this

sit-uation make the use of groups and group projects in a classroom setting ineffective; it also can result in hurting the grades of students who work.

Conclusion

The ability to be a team player is one of the top characteristics that employers desire in a prospective employee. Col-lege and university professors across the United States try to introduce students to the benefits of teamwork by assigning group projects. Using a game-theoretic approach, groups and group projects in a classroom setting fail to achieve the expected results. Because of the nature of the classroom setting, not only does the problem of free riding intensify, but it may result in making less motivated students proficient free riders. The mod-els in this study indicate that the use of groups and group projects as pedagogi-cal tools should be reconsidered. The models also indicate that penalizing less motivated students for free riding is not enough. Unless there is a reward for industrious students for carrying the less motivated ones along, the industrious student will be short-changed in terms of grades.

REFERENCES

Bartlett, R. L. (1995a). Attracting “otherwise bright students” to Economics 101. American Economic Review,85(2), Papers and proceed-ings of the 107th annual meeting of the Ameri-can Economic Association, 362–366. Bartlett, R. L. (1995b). A flip of the coin—A roll

of die—An answer to the free-rider problem in

economic instruction. Journal of Economic Education,26(2), 131–139.

Batra, M. M., Walvoord, B. E., & Krishnan, K. S. (1997). Effective pedagogy for student-team projects. Journal of Marketing Education,19, 26–42.

Becker, W. E., & Watts, M. (2001). Teaching methods in U.S. undergraduate economics courses. Journal of Economic Education,23(3), 269–279.

Benzing, C., & Christ, P. (1997). A survey of teaching methods among economics faculty. Journal of Economic Education, 28(2), 182–188.

Bowen, H. K., Clark, K. B., Holloway, C. A., & Wheelwright, S. C. (1994). Make project the school for leaders. Harvard Business Review, 72(5), 131–140.

Comer, D. R. (1995). A model of social loafing in real work groups. Human Relations, 48(6), 647–667.

Goodsell, A., Maher, M., & Tinto, V. (Eds.). (1992). Collaborative learning: A source book for higher education. University Park, PA: National Center for Teaching, Learning, and Assessment.

Hamilton, B. H., Nickerson, J. A., & Owan, H. (2003). Team incentives and worker hetero-geneity: An empirical analysis of the introduc-tion of teams on productivity and participaintroduc-tion. Journal of Political Economy,111(3), 465–497. Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1991). Cooperative learning: Increased col-lege faculty instructional productivity. Wash-ington, DC: The George Washington Universi-ty, School of Education and Human Development. (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 4)

Kerr, N. L. (1983). Motivation losses in small groups: A social dilemma analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 819–828.

McCorkle, D. E., Diriker, M. F., & Alexander, J. F. (1992). An involvement-oriented approach in a medium-sized marketing principles class. Journal of Education for Business, 67(4), 197–205.

McKinney, K., & Graham-Buxton, M. (1993). The uses of collaborative learning groups in the large class: Is it possible? Teaching Sociology, 21(4), 403–408.

Moore, R. L. (1998). Teaching introductory eco-nomics with a collaborative learning lab com-ponent. Journal of Economic Education,29(4), 321–329.

Rau, W., & Heyl, B. (1990). Humanizing the col-lege classroom: Collaborative learning social organization among students. Teaching Sociol-ogy,18(2), 141–155.

Strong, J. T., & Anderson, R. E. (1990). Free-riding in group projects: Control mechanisms and preliminary data. Journal of Marketing Education,12(2), 61–67.

Williams, D. L., Beard, J. D., & Rymer, J. (1991). Team projects: Achieving their full potential. Journal of Marketing Education, 13(2), 45–53.

TABLE 4. Instructional Model 6: Payoffs Matrix

k – 2other k – 1other

students: students: kother students:

work work work

Studenti

Works Project grade: F Project grade: A Project grade: A Does not work Project grade: F Project grade: F Project grade: A