F

RONTIER OF

C

ONTROL

KERRYBROWN,∗SUSANNEROYER,∗∗JENNIFERWATERHOUSE∗ANDSTACYRIDGE∗

I

t is argued that adopting a networked organisational model improves organisational performance and provides opportunities for innovation and creativity. The model is premised on introducing a range of information and communication technology (ICT) into the work environment. ICTs establish a fundamentally different interface between workers and their tasks and also connect managers and workers in new ways that require re-conceptualising of labour management relations. This process necessitates adapting ex-isting organisational structures and systems to account for changes in the way work is scheduled and organised and the way workers are managed. It is argued that organisa-tions implementing such new organisational forms create non-traditional organisational boundaries and fewer bureaucratic structures through forming networks. These network arrangements may present an opportunity for shifting the labour management control nexus.INTRODUCTION

Industrial society is characterised by the rise of bureaucratic hierarchies and the development of the managerial profession (Braverman 1974). Labour Process Theory (LPT) emerged as a means of analysing labour management relations in capitalist workplaces. Labour Process Theory suggests that the fundamental role of management is the conversion of labour power into labour effort to support the accumulation of capital (Braverman 1974). Labour effort is maximised through, among other things, tight managerial control. The interdependence of labour and management in negotiating effort and power relations thus results in a frontier of control and conflict emerges when this frontier is crossed (Dufty & Fells 1989). However, over time the traditional command and control mechanisms of man-agerial authority have undergone transition as organisational forms have altered (Markuset al.2000).

Within the new organisational environment of post-industrial society, it is suggested that new organisational forms are replacing the traditional hierarchi-cal style of management (Jackson & Stainsby 2000). Castells (2000) identifies the organisational form in the ‘new economy’ as ‘information networking’. For organisations, networked structures represent a possible new organisational form that may be selected to adapt to meet the challenges of the new environment. Networked organisational forms combine elements of team cooperation within enterprises as well as across the borders of an enterprise. In this way, networks

∗School of Management, Queensland University of Technology, GPO Box 2434, Brisbane, QLD,

Australia∗∗International Management, Universitat Flensburg, Munketoft 3b, D-24937 Flensburg,

Germany.

establish an organisational form that has the flexibility to transcend traditional organisational boundaries and the rigidities of bureaucracy and avoid the adver-sarial relationships inherent in contractual market-based agreements.

Such networked arrangements rely on information and communication tech-nology (ICT) as a means of linking functions and dispersed sectors (Castells 2000). Relationships between relatively autonomous parties therefore exist within a ‘vir-tual reality’. Through the use of ICT, porous organisational boundaries and fewer bureaucratic structures, networks may provide an opportunity for a shift in the labour management control nexus. The networked organisational form is the focus of this paper. The paper examines the potential dislocation of the labour management control nexus within networked organisational structures using ICT and posits the possibility of a self-directed and empowered workforce or the re-location of the locus of control with either new forms of managerial control or with peers at the level of the team.

This research examines the implications and outcomes of adopting networked organisational arrangements in relation to managing virtual workforces. In sum-mary, two research questions are addressed: (i) are the new organisational forms a challenge to managerial power; and (ii) do these developments actually change the frontier of control?

A case study of a public sector organisation adopting a networked organisa-tional model through a refined project management approach was undertaken to examine managing and utilising virtual, networked workforces. The Department of Main Roads, Queensland, Australia presents an ideal case for examining the research question as the department is in the process of shifting from a traditional hierarchy to a networked form.

This paper addresses the research questions through first presenting an overview of the emergence of new organisational forms. Networks are then de-scribed and examined. The ways that ICT may be used within networks to co-ordinate activities are explored, leading to a discussion about how networked organisational forms and ICT may act as a means to alter the locus of control. The case study of the organisation is then introduced and consideration is given as to whether the case demonstrates a shift from control to cooperation.

NEW ORGANISATIONAL FORMS: DEVELOPMENT AND UNDERLYING FACTORS

Factors such as the globalisation of business activities and strongly rising fixed costs have led many organisations to expand business activities beyond the tradi-tional firm boundaries (Picotet al.1998). Traditional organisational boundaries have blurred and more hybrid organisational forms between market and hier-archy have come into existence to overcome entry barriers to new global mar-kets, access market-specific knowledge and implement global economies of scale (Camuffo 2002). Firms have also adapted their internal structures to include in-ternal and exin-ternal modularisation in many areas and project teams that work on a geographically dispersed basis.

outsourcing and contracting. At the same time, the costs and benefits of hierarchy are recognised as useful prescriptions for resolving various organisational design problems (Teece 1984). Transaction cost economics considers hybrid organisa-tional forms between market and hierarchy to be efficient in different situations. Justification for the selection of hybrid forms includes transactions charac-terised by high uncertainty or complexity and high specificity and strategic rel-evance. These factors force firms to work together with partners in different organisational forms. Hybrid forms also enable partners to exchange informa-tion efficiently by being able to overcome problems with informainforma-tion complexity (Arrow 1971), sticky information (Hippel 1994) and information spillovers (Picot et al.2002: 191). Cooperative forms, including hybrids, are viewed as capable of reducing risk and uncertainty, overcoming knowledge, capital and capacity con-straints and managing information exchange problems in an increasingly dynamic and complex business environment.

Cooperative forms can be simple licensing agreements, joint ventures, different kinds of (mutual) capital investments, long-term contracts with suppliers with a dual sourcing option as well as franchise organisations or dynamic networks (for an overview see Picotet al.2002: 189–212). Networks, described in the next section, therefore represent a new organisational structure that can be selected to address the changing business environment.

NETWORKED ORGANISATIONAL FORMS AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT Networked organisational forms are characterised by independent people and groups acting as independent nodes, linking across traditional firm boundaries. Such networked organisational forms usually have multiple leaders and voluntary links as well as a variety of interacting levels (Lipnack & Stamps 1994). Hierar-chical elements are exchanged for cooperative structures to achieve a common goal. These new features influence the relationship between the organisational members. Networked organisational structures are an option for smaller firms to retain ‘the entrepreneurial spirit’ of smaller units while realising economies of scale. Networks are also an organisational alternative for larger firms that want to achieve the same but from the opposite position, that is, to become more flexible and achieve entrepreneurial spirit without losing scale and scope advantages.

The term networked organisational structure, therefore, can be considered as a general term used for organisations that react to environmental challenges by creating more flexible organisational structures containing linked teams and in-dividuals who interact with each other on different levels to achieve set objectives together. Networks form through the different constellations of teams and indi-viduals working together within the firm and across traditional firm boundaries. Networked organisational structures are cooperative forms inside and/or between relatively autonomous organisational units or firms that are bound in a net of re-lationships (Sydow 2003: 1).

to bring together experts in different fields to achieve the successful completion of a particular project. This approach requires parties to form ‘self-managing, fluid teams’ requiring a different cultural and managerial orientation to that found in hierarchical, bureaucratic organisations (Lewiset al.2002). Both networks and project management are made possible through ICT and become ‘virtual’ in that teams and individuals work together across space and time as well as organisational boundaries.

INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY

Information and communication technology plays a major role in the context of the changing environment and changing organisational structures. The infras-tructure of the twenty-first century implies sophisticated communication, trans-portation, and computing technologies (Lynchet al.2000), enabling the efficient coordination of extensive activities.

Within networked organisational forms, studies tend to focus on the techno-logical aspects of virtual networks by examining the utilisation of ICT and the interface between ICT and its users (Wilson 1999). To adopt a networked or-ganisational model, it is necessary to exploit technologies in the area of ICT to provide the framework and interconnectedness that mediate traditional organisa-tional structures (Herndon 1997). ICTs thus play a dominant role in the success of networked organisations in providing the basis for these organisational forms. The new technologies such as video conferences, email functionalities, workflow management or groupware make these new organisational forms possible.

Two other significant aspects of virtual network organisational forms relate first to identifying the characteristics of these emerging work arrangements and second the way in which labour is deployed to undertake tasks in the virtual workplace (Markuset al.2000). Networked forms may, for example, comprise temporary contracted teams that work across organisations (Markuset al.2000) or groups such as those formed to deal with intractable social issues such as poverty (Provan & Millward 1995), and these forms of organisation cut across traditional management and labour utilisation techniques. The second aspect considers how traditional management approaches may need to change to respond to these dif-ferent organisational forms. Within networked organisational forms, new forms of division of labour may thus become possible and success in shifting the frontier of control appears achievable.

THE FRONTIER OF CONTROL IN NETWORKED ORGANISATIONS

In examining the social construction of virtual workplaces, the traditional forms of control through formalised rules and close supervision are no longer tenable and new norms relying on output rather than input-based criteria need to be im-plemented (Panteli & Dibben 2001). These new organisational forms may have the potential to disrupt the cycle of control-resistance by workers and manage-ment postulated by labour process theorists (e.g. Braverman 1974). However, May (2002) contends that, unless intellectual property relations are codified to acknowledge the contribution of labour, there is little prospect of breaking the management domination of labour.

A crucial success factor in overcoming the control–conflict–resistance cycle within a network organisational form therefore becomes the ability to cooperate (Waterhouseet al.2002). If cooperation is a ‘higher order’ mode of work organi-sation in networked arrangements, then this requires a different conceptualiorgani-sation of labour management relations. Traditional models of labour management rela-tions have been premised on a notion of conflict as underpinning the employment relationship with a specific focus on conflict at work (Godard & Delaney, 2000). To manage this conflict, managerial practice has focused on maintaining author-ity to control the workforce. As organisations have changed form, mechanisms for control of labour management relations may also change. Due to a propensity for cultural manipulation and an inability to garner the benefits of team synergies, self-managed teams may, however, deliver a greater degree of control rather than achieve cooperation (Korac-Kakabadseet al.1999).

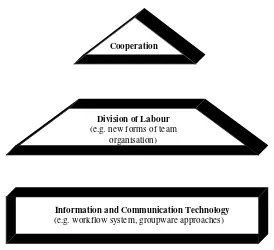

Cooperation in the form of personal relationships between the often dispersed employees in virtual teams and between different virtual teams in a network grows over time and is considered the essence of successful networked organisations (Sydow 2003). Managerial dilemmas often arise because the structure makes it difficult to have ad hoc meetings and more preparation and planning activities are necessary in this area (e.g. video conferences have to be prepared and technically scheduled in advance). Figure 1 summarises the outlined determinants of net-worked organisations and identifies the three main features of such organisations.

COOPERATION,CO-OPTATION AND CONTROL

Many approaches and existing examples in business show that research is fairly advanced with regard to success factors relating to the implementation and con-tinued use of ICT (Konrad & Deckop 2001). This situation is somewhat different in relation to the success factors of the division of labour leading to the ability to cooperate (Markuset al.2000). The ability to address issues surrounding the divi-sion of labour appears to be a central determinant in achieving cooperation within new organisational forms such as networks that utilise ICT. Moreover, cooper-ation relies on bringing together complex relcooper-ationships across cultural, technical and structural frameworks.

Figure 1 Relevant determinants of networked organisations.

Information and Communication Technology

(e.g. workflow system, groupware approaches)

Division of Labour

(e.g. new forms of team organisation)

Cooperation

and behaviour necessary to achieve cooperation is more difficult within such or-ganisations and there may be a tendency to maintain the management locus of control.

In the networked organisation management is still necessary, but their role in controlling the labour process changes, because new forms of labour division need coordination, rather than control, to be successful. Managerial strategies and im-peratives, however, require a new kind of thinking and action. Instead of accurate planning, project goals and visions gain relevance; mobilising resources becomes more important than organising a firm in a traditional sense; empowerment has the potential to replace control; direct instruction loses importance in favour of long-term goals and internal orientation is widened to an external orientation (Handy 1995).

Therefore, the question arises as to whether organisations moving to networked structures are on a path from control to cooperation or whether control is merely changing form. For example, forms of direct control may lose relevance in favour of controlling work results. Small project groups make it possible to attach exact responsibilities for product outputs as well as performance results. In this way, control, monitoring and coordination are easier in smaller project groups enabling easier implementation of performance-oriented reward systems as well as social control through group dynamics (Picotet al.1999).

organisation appears necessary as it brings together the stakeholders and employ-ees to jointly achieve organisational goals (Royeret al.2003). Cooptation differs in that the driver is top-down and joint action is achieved through assimilating diver-gent groups to the dominant culture (Brownet al.2002). How cooperation occurs and the degree to which cooptation resembles or extends into coercion needs to be explored in the context of an organisation changing to a networked form and through a research design that captures both process and different stakeholder experiences.

METHODOLOGY

The research project examined the management and control issues surrounding the implementation of virtual teams across organisational boundaries. A case study of an organisation preparing to shift to networked organisational structures was used to examine the process of moving to a networked structure and the managerial and employee responses to this shift.

The data collection commenced with introductory interviews with senior managers that allowed identification and exploration of managerial approaches (Sekaran 1992). These managers were chosen because of their strategic position in the organisation. Two focus groups with middle managers were undertaken, followed by four focus groups with employees from various levels and occupa-tions. This procedure ensured that all major groups of the organisation were covered including different hierarchical levels, administrative, operational, pro-fessional and technical staff. Rather than achieving proportional representation, interviewees were purposefully selected from volunteers within the department to obtain widespread perspectives. Interview and focus group participants were therefore chosen according to principles of purposeful sampling (Patton 1990).

One-on-one semistructured interviews were conducted with a range of senior officers including a group interview with all regional directors in the department. These directors are geographically dispersed, being located within their regions throughout the state of Queensland. Given their role as instigators and in some cases, also as recipients of change, it was important to gain regional directors’ per-ceptions of what changes they were seeking to implement and their perper-ceptions of what more senior management in the department were seeking to achieve. Semistructured interviews were considered as the most suitable method to ac-complish this as they allowed the main topics and general themes to be targeted through specific questions, while allowing the freedom to pursue other relevant issues as they arose (Maykut & Morehouse 1994). These research methods were designed to draw out managerial attitudes towards, and understanding of, net-worked arrangements and their implications for labour management relations in their organisation.

CASE STUDY

1998). It is a geographically dispersed organisation consisting of four regional and 14 district offices (Main Roads 1998). QDMR is also a technically oriented organisation with high-level expertise in construction and engineering which is undergoing significant change processes. One such change is a planned shift to a networked organisation with the priority and focus changing from construction of infrastructure projects to managing and policy formulation (Main Roads 2000). Up to the early 1990s, QDMR was characterised by a bureaucratic structure and culture. A hybrid organisation has evolved through a purchaser–provider split where the organisation is now comprised of half commercialised/business struc-tures and half bureaucratic administrative strucstruc-tures. The case study is concerned with the commercial operations arm of QDMR, RoadTek. It provides civil infras-tructure delivery to local governments, the private sector and the non-commercial arm of QDMR through the purchaser provider arrangement (Ryanet al.2000).

In moving from a regionally based organisation to a statewide operation, Road-Tek aims to achieve vertical and horizontal integration of its activities. The goal is stated to be a self-driven organisation with high levels of leadership skills and a culture of innovation. Although ICT as an integrated business process is an important aspect of the project management approach aspired to, another crucial aspect is communication and the linking of teams through a relational approach to stakeholders. The vision for the organisation reflects notions of self-learning, empowerment and networked organisational structures facilitating learning, in-formal education and alliances.

NETWORKED ORGANISATIONAL APPROACH

The initial changes implemented in RoadTek sought to shift the previous bureau-cratic program approach to embrace a ‘commercial project management culture’ through

Ensuring the implementation of a common and consistent business system and pro-cess; the development of a project management culture within commercial operations (Lewiset al. 2002).

The objective of these changes is to become a networked organisation to gain economies of scope, improve innovation and introduce flexible workforce utilisa-tion. Therefore, QDMR seeks to achieve a shift from the traditional bureaucratic policy, culture and structure of a public sector organisation and forego authori-tarian positions to enter into true network relationships. An overarching structure has to be found for both parts of the current organisation that is compatible with the new organisational order.

innovative ICTs formed the basis to shift to a new level of interconnectedness through networks. In particular, Project 21 was an innovative program that has arguably affected the delivery of new forms of labour management relations.

Project 21 was not only an integrated ICT to improve organisational processes and business systems but also a change management program. The aim of Project 21 was to shift RoadTek away from a ‘hierarchical, functional structure’ to a structure ‘based on project teams’ through implementing ICTs that integrate business systems (Lewiset al. 2002). Project 21 adopted a holistic approach to achieving these aims by focusing not just on operations and systems but also on financial and delivery outcomes, the management of stakeholder relations and a training and development program that sought to achieve skill-based career progression.

Information and communication technologies provided the platform for shift-ing to a networked organisation. However, the introduction and use of ICTs such as intranets and human resource information systems did not initiate the move to a network. The research findings indicate that recognising the inefficiencies arising from system inconsistencies in the numerous highly autonomous regional offices, the implementation of Project 21 and the adoption of a project manage-ment approach provided the impetus to explore the notion of virtual teams in networked organisational structures.

NEW ORGANISATIONAL FORMS—DIVISION OF LABOUR

The project management approach together with a need to develop a way of providing consistency of operations and flexibility of functions acted as both an introductory phase and also a continuing feature in the shift towards networked organisational arrangements. A project is an assignment that has to be finalised in a specific time frame, is unique and therefore not integrated into established organisational structures. One senior manager commented that the project man-agement approach was about

Getting them [the districts] to break out of their silos because they have district and group responsibility and they needed to think about the group as a whole, statewide.

In mid-2001, the director of RoadTek commented:

It’s about getting the whole organisation to operate on project management princi-ples. Whether you are the person who orders the stationery or builds the big project or road, we want to use project management as the way to do business.

One District Director stated in relation to the implementation of project management:

All our future projects will be networked projects—better outcomes regarding objec-tives and goals when people are focused on the project rather than where they come from.

adopt an organisationwide perspective. In project teams, the property rights are centralised in a small organisational unit that is technically able and also moti-vated to maximise project success (Picotet al.1999). What was observed within the Department of Main Roads was the coexistence of these autonomous work groups alongside a traditional functional hierarchy that was necessarily changing to allow it to successfully operationalise project management. The autonomy of the regions, while providing a strong identity for localised work groups, worked against achieving synergies across RoadTek. Mobility between regions was con-sidered costly and inefficient for the organisation as employees needed retraining for region-specific systems and work duties.

Therefore, another element introduced simultaneously with the project man-agement concept was working towards a standardised statewide integrated sys-tem (Lewiset al.2002). This approach was not specifically driven by the project management concept, but rather from a need to align the disparate geograph-ical branches of the department, partly to gain economies of scale and scope and partly, to enable a mobile, flexible workforce statewide to deal with uneven workflows.

Senior management within the department wanted to achieve economies of scale by rationalising the workforces of many different regions. This was to be achieved through both systems alignment and providing consistent staff training throughout the state. A senior manager commented that maintaining the inde-pendence of the regions came at a high commercial cost. The autonomy of the regions had acted as a force for employees to adopt a relatively narrow focus on their functional and geographical area.

The new division of labour focused on achieving higher levels of flexibility of the workforce, specifically staff mobility. Organisational problems identified by the District Manager was the ‘inability to move people around the organisation’, whereas another suggested that teams would now need to be flexible and mobile:

We will either have another large project for them or move them onto minor works. Project Management brings people in as needed.

In this way, it was argued that the project management approach dislocated managerial control of employees in their day-to-day work by shifting the teams between different kinds of work. It was considered to be the start of a dismantling of traditional patterns of labour management relations. Furthermore, the tem-porary and mobile nature of work teams required an emphasis on new forms of communication to connect geographically dispersed members.

A benefit of adopting networked organisational arrangements was therefore about changing the work environment through the development of sophisticated ICTs:

People are thinking laterally and they’re looking at having the technology there, satellite technology, GPS [Global Positioning System] and you’ve got designers there linking that technology onto their plans, to survey it...having it all digitised then

It was contended that a further benefit associated with a highly mobile work-force in a networked organisation was the ability to bring in expertise when projects required specific or high level skills. One District Manager cited the case of the Environmental Officer who could be brought from another region into their more remote region when needed. The ability to shift specialist officers around to different projects displaces the managerial locus of control exercised at a particular workplace.

The traditional division of labour has been under threat from moves to develop a team-based approach and a statewide operational focus. The senior managers within the department saw an overriding need to deploy teams to different project sites and that shift started to break down the geographical configurations of a workforce located within specific regions.

CHANGING LABOUR MANAGEMENT RELATIONS—COOPERATION

Mobilising the workforce and establishing geographically dispersed and tempo-rary project management teams offers the possibility of changes in mechanisms of management control and the establishment of cooperation. The published ob-jectives of the department suggest that cross-cutting initiatives are integral to the operation of the workplace at a regional level and are an expected manage-rial goal. Senior departmental managers have recognised these new organisational forms require new sets of managerial strategies and imperatives. A senior manager commented that:

We generally have got to get used to the idea of being able to work in an environment where we don’t always control the people we work with, they don’t always report to you, we need to be able to work in these virtual teams or whatever. Because one of the things we’re finding is if you want to be successful you’re going to have to work in a whole lot of different ways. You need to be very fluid to meet customer needs so you’re going to have to form and re-form.

This manager went on to suggest that the introduction of the ICTs in Project 21 paved the way for a completely new way of managing employees:

I think that’s one of the things we’re starting to learn out of Project 21 now is really you’ve got to get a culture that has an acceptance of people being able to manage people without controlling them.

The methods of implementing the changes were acknowledged by the Director of Roadtek as requiring both top-down and bottom-up implementation processes that took into account employee attitudes and interests.

For one District Director, a networked organisation brought standardisation and consistency. It also could deliver members of the organisation onto a ‘similar wavelength’ and thus become the vehicle for developing ‘more common views of the world’. For another senior manager, the introduction of a networked organ-isation not only permitted better ‘value for dollars’ but also allowed a ‘focus on higher level issues’.

arrangements with a focus on cooperation. For one employee, the cooperative approach meant that their ideas were heard and opinions valued. Another em-ployee felt that there was the possibility to shift the frontier of control, ‘since the relationship framework, there is more room in RoadTek to challenge things. The general manager encourages people to challenge things’. Another employee noted the change from the previous culture as a change to greater flexibility ob-serving that, ‘traditionally Main Roads culture is to build monolithic systems and processes that inhibit flexibility while we are trying to build things more flexibly’.

The shift was not perceived specifically as a move to a networked organisation, but to new forms of organisational arrangements.

So where RoadTek is thinking about how we can solve the problem by a different management style or incorporate project management principles at all projects...

Main Roads is just throwing resources at it.

The need for a cooperative approach to implementing networked organisa-tional arrangements was cited as a significant departure from tradiorganisa-tional organ-isational approaches to managing employees. However, it is very early in the process of changing to new arrangements. Lynchet al.(2000: 409) argue that a public sector organisation implementing a virtual team approach ‘increases the availability of talent and expertise, creates synergy and provides different per-spectives’. However, a threat lies in weakening the bonds between employer and employees as this may militate against employees remaining with the organisa-tion and simultaneously weaken employers’ sense of responsibility for employees. Korac-Kakabdaseet al.(1999) further warn that decentralised teams may lapse into dysfunctional behaviour through the ‘dark side’ of increased managerial control rather than achieving greater innovation and empowerment.

The potential for such increased managerial control exists in a number of ele-ments of Project 21. In the design of integrated and standardised business systems across RoadTek exists the possibility of significant control of the labour process. The concept of an integrated technology guiding a construction project from survey through to final construction suggests, as proposed by Laurel (1991), that in the purposeful design of virtual workforces exists the possibility to both control and be controlled.

Within networked organisations, management therefore appears far from being obsolete but is more important than ever. Management, however, has to take place within new organisational forms such as the combination of traditional hierarchy and project management in the QDMR case. This case suggests that management is aware of the need to manage without controlling, but that managing project teams without controlling them is still some way to being achieved. Direct con-trol, however, loses relevance in favour of controlling work results. This occurs alongside the problems associated with situations where output is hard to measure or takes time to achieve such as in the often large-scale projects undertaken by QDMR.

It appears from this case that it is important that both top-down implementa-tion from management and bottom-up implementaimplementa-tion from within the groups and project teams is fostered. Top-down implementation was used in QDMR to achieve consistency of systems and processes to enable espousal of project man-agement principles. Cooptation therefore appears to have occurred to assimilate divergent groups towards the dominant hierarchical culture. In terms of coop-eration, QDMR employees saw a shift to new organisational forms but did not necessarily understand the network philosophy. Such a situation may ultimately have a negative impact on the success of shifting to a network organisational form. Networked organisations do not work without cooperation between employees and employers (Royeret al.2003). Traditional control instruments become in-effective and the statements of QDMR managers underline this. However, May (2002) argues that control is more important than cooperation leading to the implementation of control systems in many organisations, often through ICT. Potentially opportunistic human behaviour leads to risks from a principal agent point of view (Rumeltet al.1991) in this context. The problem of opportunistic behaviour in cooperative work teams cannot be solved by contracts as a tradi-tional way out of this dilemma. Therefore other possibilities for the management of labour have to be identified. These are argued to be found in the area of trust and reputation that lead to successful cooperation (Royeret al.2003).

In considering the empirical evidence presented, team workers in an organ-isation shifting from a traditional hierarchy to a networked organorgan-isation may experience a shift in their relationship with management to cooperation, but the relationship may also not be completely free of control. In networked organisa-tions there may be a shift to new output-oriented forms of control and the use of cooptation. The insights into the case of QDMR as an organisation on the way to a networked organisation suggest that a balance between control, co-optation and cooperation is difficult to achieve but that this is necessary to successfully operationalise a networked organisation.

CONCLUSION

structure and function allied to day-to-day management and thus has the potential to change the nature of managerial control.

The process of shifting to a networked organisation necessitates adapting ex-isting organisational arrangements such as the traditional forms of labour divi-sion and conventional managerial practices to account for changes in the way work is scheduled and organised and the way workers are managed. It has been argued that organisations implementing networked organisational forms create non-traditional boundaries and fewer bureaucratic structures through the forma-tion of networks. Labour Process Theory posits that the frontier of control is maintained by management who seek to use authority and coercion to control the workforce. Network arrangements may however present an opportunity for a shift in the labour management control nexus through eliminating the ability for direct control, potentially leading to greater reliance on cooperation to achieve organisational goals.

The findings indicate that senior managers within QDMR recognise that tra-ditional employee control mechanisms are not applicable to the new network ar-rangements, acknowledging the need for a change to ‘managing not controlling’. Although the shift to a networked organisation was in its early stages, the ap-proach signalled that senior managers were seeking a more cooperative apap-proach to labour management relations. Employees acknowledged the emergence of new organisational forms, but did not conceive of the new approach as a networked organisation and did not necessarily conceptualise labour management relations as cooperative. However, the response of middle managers, traditionally the gate-keepers between senior management and employees, may be crucial in negotiating the implementation of virtual teams in the new networked organisation.

The management of employees dislocated from traditional forms of managerial authority through the adoption of networked organisational forms may enable a shift in the frontier of control. With their reliance on virtual teams undertak-ing project-based work, networked organisational forms offer the prospect of transforming traditional managerial roles. The case study indicates that man-agers recognise the need to change their reliance on direct managerial control of workers in order to establish a networked organisation. Although employees recognised new forms of cooperation through consultative mechanisms, they also identified that these new arrangements may also usher in new forms of managerial control.

REFERENCES

Arrow KJ (1971)Essays in the Theory of Risk-Bearing. Chicago: Markham.

Braverman H (1974)Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Brown CJ (1999) Towards a strategy for project management implementation.South African Journal of Business Management30: 33–9.

Brown K, Callaghan A, Keast R (2002) The role of central agencies in ‘crowded’ policy domains. Sixth International Research Symposium on Public Management 8–10 April 2002, University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

Castells M (2000) Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society.British Journal of Sociology51 (1): 5–24.

Dufty NF, Fells RE (1989)Dynamics of Industrial Relations in Australia. Sydney: Prentice Hall. Godard J, Delaney JT (2000) Reflections on the “high performance” paradigm’s implications for

industrial relations as a field.Industrial & Labor Relations Review53 (3): 482–502. Handy C (1995) Trust in the virtual organisation.Harvard Business Review73 (3): 40–50. Herndon S (1997) Theory and practice: Implications for the implementation of communication

technology in organisations.Journal of Business Communication34 (1): 121–9.

Hippel Ev (1994) Sticky information and the locus of problem solving: Implications for innovations.

Management Science40: 429–39.

Jackson P, Stainsby L (2000) Managing public sector networked organisations.Public Money and ManagementJanuary–March: 11–16.

Konrad A, Deckop J (2001) Human resource management trends in the USA.International Journal of Manpower22 (3): 269–278.

Korac-Kakabadse N, Korac-Kakabadse A, Kouzmin A (1999) Dysfunctionality in “citizenship” behaviour in decentralized organisations: A research note.Journal of Managerial Psychology14 (7/8): 526–544.

Laurel B (1991) Virtual reality design: A personal view. In: Helsel SK, Roth JP, eds,Virtual Reality: Theory, Practice and Promise. Westport: Meckler Publishing.

Lewis D, Waterhouse J, Szymczyk-Ellis J (2002) From bureaucracy to project management: A cultural leap.Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government8 (1): 38–45.

Lynch TD, Lynch CE, White RD Jr (2000) Public virtual organisations.International Journal of Organisational Theory and Behaviour3 (3/4): 391–412.

Main Roads (1998)Annual Report 1997/98. Brisbane: Department of Main Roads, Brisbane: Queens-land Government Printer.

Main Roads (2000)Internal Correspondence. Queensland Government Printer

Markus M, Manville B, Agres C (2000) What makes a virtual organisation work.Sloan Management Review Fall13–26.

May C (2002) The political economy of proximity: Intellectual property and the global division of information labour.New Political Economy7 (3): 317–42.

Maykut P, Morehouse R (1994)Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide. London: Falmer Press.

Moaty P, Mouhoud EM (1994) Information et organisation de la production: vers une division cognitive de travail.Economee Appliquee46 (1): 47–73.

Panteli N, Dibben M (2001) Revisiting the nature of virtual organisations: Reflections on mobile communication systems.Futures33, 379–91.

Patton M (1990)Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. California: Sage Publications. Picot A, Dietl HM, Franck E (1999) Organisation. Eine ¨okonomische Perspektive, 2nd edition.

Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Picot A, Reichwald R, Wigand RT (1998)Die grenzenlose Unternehmung, 3rd edition. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Provan KG, Millward HB (1995) A preliminary theory of interorganisational network effectiveness: A comparative study of four community mental health systems.Administrative Science Quarterly

40: 1–33.

Royer S, Simons RH, Waldersee R (2003) Perceived reputation and alliance building in the public and private sector.International Public Management Journal6 (2): 199–218.

Rumelt RP, Schendel DE, Teece DJ (1991) Strategic management and economics.Strategic Man-agement Journal12 (Winter Special Issue): 5–29.

Ryan N, Brown K, Flynn C (2000)Corporate Change in the Department of Main Roads. Report to the Department of Main Roads.

Sekaran U (1992)Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 2nd edition. Toronto: Wiley.

Sydow J (2003)Management von Netzwerkorganisationen. 3rd edition, Wiesbaden: Gabler. Teece DJ (1984) Economic analysis and strategic management.California Management Review26 (3):

Waterhouse J, Brown K, Little M (2002) Organisational culture, strategic choice and the labour process: A model developed on Hegelian principles, Celebrating Excellence, Vol. 1, Refer-eed Papers. In: McAndrew I, Geare A. eds.,Proceedings of the 16th AIRAANZ Conference, Queenstown, 6–8 February.

Williamson OE (1991) Strategizing, economizing and economic organization.Strategic Management Journal12 (Winter Special Issue): 75–94.