Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 22:51

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Toward Leadership Education That Matters

John Nirenberg

To cite this article: John Nirenberg (2003) Toward Leadership Education That Matters, Journal of Education for Business, 79:1, 6-10, DOI: 10.1080/08832320309599080

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320309599080

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 55

View related articles

Toward Leadership Education

That Matters

JOHN NIRENBERG

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Shinawatra University Bangkok,

Thailand

he Porter and McKibbin (1988)

T

report was the opening salvo in a campaign of “shock and awe” intended to awaken business schools to the need for change. As in the current situation in Iraq, the liberation of the professors was not followed by a sympathetic uprising embracing change. Instead, a long, sim- mering campaign followed. Every few years, the allied forces for change would launch a renewed campaign only to see it fall on deaf ears (Hambrick,1994; Mowday, 1997; Pfeffer

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Sutton,2000; Pfeffer & Fong, 2002; Rynes, Bartunek, & Daft, 2001).

The Professoriate as Its Own Worst Enemy

The problem is twofold. First, busi- ness schools themselves are not inclined to change from within and are impervi- ous to change from without. Neverthe- less, professors preach to students about the rapidly changing, paradigm-shifting, complex environment of business. According to them, this turbulent busi- ness environment has led to a disman- tling of the old hierarchies in favor of responsive, innovative networks; a con- stant search for improved processes and new products and services to offer to an increasingly fickle customer; and train- ing and empowering of employees for the purpose of serving a single, coherent

ABSTRACT. Given the recent wave of corporate scandals, the very credi- bility of business schools’ handling of leadership education is now in ques- tion. Alternative forms of leadership education are taking root and most likely will be well established before business schools enter the competi- tion. In this article, the author exam- ines institutional and personal barriers preventing change and offers sugges- tions for a holistic, practical approach to leadership development.

vision. All of this is occurring while business schools remain organized to serve an industrial world that no longer exists.

In business schools, knowledge is still compartmentalized, learning remains a teacher-centered exercise, and the profes- soriate has so diminished its contact with the business world that it barely under- stands the conditions that real managers encounter. In this regard, our understand- ing of what managers do is based on a lone researcher’s 30-year-old observa- tions (Mintzberg, 1973) of a handful of executives. A considerable number of current textbooks still reference this one source as a basis for study. The problem is significant: Only 53% of submissions to a special research forum on knowledge transfer between academics and practi- tioners reflected direct contact with prac- titioners (Rynes et al., 2001).

In this article, I argue that the culture of business schools remains heavily ori-

ented toward the production of tradi- tional forms of research about conven- tional issues. This culture reinforces its perpetuation through two insidious methods: (a) promotion and tenure deci- sions that exclusively reward conven- tional academic behavior and (b) the fiercely guarded professorial privilege of being treated as sole proprietors, which inhibits cooperation between professors of varying disciplines. Com- partmentalized departments offer cours- es taught by individual professors grant- ed virtual sovereignty in the classroom as long as they publish in journals cho- sen according to their degree of statisti- cal rigor. In addition, the hiring and reward system is designed more for cloning than for challenging the con- ventional wisdom and traditional prac-

tices. In

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

this kind of teaching environ-ment, the personal practice of leadership behavior is unnecessary, even misguided.

Regarding the latter point, the behav- ioral practice of leadership-if it is offered at all-is derided as a “soft skill,” an unnecessary part of the cur- riculum, too indeterminate and unpre- dictable or too “touchy-feely” to be meaningful. This tendency is evidenced by the elective status of the subject in most business schools. Harvard MBAs, like most, only take a single relevant course, Leadership and Organizational

6

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

JournalzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessBehavior, and Northwestern’s Kellogg School also requires only a single course, Strategies for Leading and Man- aging an Organization. Whether gradu- ates of such MBA programs succeed as leaders or not will depend almost entire- ly on happenstance without any deliber- ate effort on the part of the schools that educated them.

The second problem is in the body of knowledge itself. The conceptualization and definition of leadership in business schools and the methods used to teach it are so abstract and fragmented that a student who has had the fortitude to memorize Fiedler’s (1 967) contingency situations and Vroom and Yetton’s (1973) decision-making methodology will know much about complicated models but nothing about his or her own ability to use them-to actually lead. Because we value research about lead- ership, that is what we teach. Faculty members in business programs have removed the experience and practice of leadership from the classroom.

Consider the following thought exper- iment to grasp the unfortunate situation that we face: Look outside your window. What do you see? Describe it to your- self, and attempt to derive meaning from what you see. Obviously, there is no sin- gle truth. One individual may become saddened by the bleakness of an inner- city, trash-strewn wasteland; another

might become so engrossed

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

as to betransported back to a scene in her youth. A single interpretation of perspective is not the point; rather, the exercise demon- strates personal meaning and whether or not an individual’s experience is per- ceived in a positive or negative way. The following example shows how almost all researchers would describe the same scene in a management journal:

There are various organic and inorganic materials in the field of vision and their

interaction effects are unstable due to the complexity of the climatic uncertainties

and low correlation between the move- ment of the rapidly decaying organic mat- ter against the slow decaying of the inor- ganic matter. Because the perspective of the viewer is subject to dynamic internal

states and is unreliable, it is highly

unlikely

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(p > .05)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

that any meaning can bederived from the one perspective.

Where is the experience of using leadership skills and placing one’s

behavior in the context of collective social action? Where is the risk-taking in leadership education and develop- ment; the classroom experimentation; the grappling with the personal aspects of students’ (and faculty members’) relationships, beliefs, values, and sense of self in a context involving social influence? In this regard, although busi- ness faculty members typically claim to be preparing students for the “real” world, they actually remove students from it during the learning process by concentrating on abstractions impossi- ble to apply and test in the real world. Perhaps this situation arises because so many professors on the tenure track have not had significant experience in doing what they are teaching, or they simply prefer the elegance of theory untainted by the messy complexity of the real world.

A Void in Graduate Business Leadership Development Concentrations

Faculty members of business pro- grams, especially those in the discipline of management, are not providing ade- quate leadership practice (development) even if we credit them with adequate theoretical leadership education. Lead- ership development just does not hap- pen during a teacher-centric course that focuses on theoretical content. Such courses are comparable to driver educa- tion classes that do not place the student behind the wheel of a car.

Although 120,OOO MBAs are granted each year, according to a survey of 5,000 human resource personnel by Develop- ment Dimensions, “82 percent of organi- zations have dficulty finding qualified leaders” (Buss, 2001, p. 45). Thus, com- panies seeking leadership must look else- where and may hire special consultants to fill gaps in capabilities of a local work force. In response to this need to develop leadership throughout an organization, Charan, Drotter, and Noel (2000) and Tichy (2002) have published texts focus- ing on the issue and have developed suc- cessful consulting practices aimed at ini- tiating in-house leadership development programs.

The lack of formal leadership devel- opment programs is echoed by

researchers recently analyzing graduate concentrations in business. Crawford, Brungardt, Scott, and Gould (2002) found 40 schools in the United States offering graduate programs in organiza- tional leadership, but only two were concentrations in an MBA program. Business schools seem to have accepted a default view that leadership is simply “what leaders do” and that leaders are simply people in positions of power over others. In that mindset, paradoxi- cally, the study of leadership is simply risk reduction and creation of conformi- ty with the desires of the boss.

All other professions-from account- ing, architecture, and engineering to law, medicine, nursing, and K-12 teach- ing-require previous or concurrent practice by staff and include student internships; counseling practica; moot courts; apprenticeships; supervisions; or other experiential components for certi- fication, such as medical residencies, student teaching, and clinical semesters for nurses.

No other professional field so dis- misses practice as a necessary compo- nent of teaching and learning. Business schools, however, have desperately, and foolishly, attempted to create a coin with only one side.

The Other Side of the Coin: Making Leadership Development Integral to Business Schools

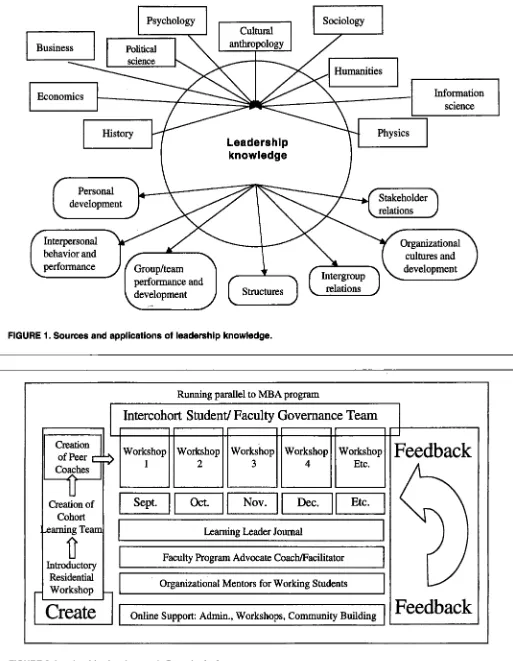

In this article, I propose an integrative model that acknowledges the various sources of leadership knowledge and their many applications (see Figure 1). The multidisciplinary nature of leader- ship knowledge is considerable. Because of the expansive nature of the discipline of leadership, more varied approaches may be required to bring relevancy into the training of leaders. Therefore, the orthodoxy of limiting learning from a single discipline taught entirely within a single school is unacceptable.

Graduate Leadership Model Proposed

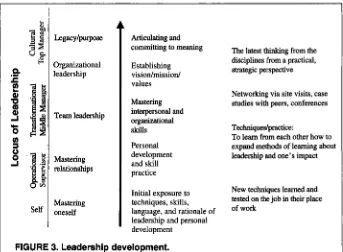

In Figure 2, I present one model of leadership development at the graduate level. The model, which includes vari-

ous elements of support and multiple

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

September/October 2003

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

7Information science

[image:4.612.50.563.42.703.2]Economics

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

.zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

FIGURE 1. Sources and applications of leadership knowledge.

r

Running parallel

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

to MBA programm

I

Intercohort Student/ Faculty Governance Team

=++pi

Coaches Workshop WorkshopL U I I U I C I

,

i:arningTeaml

I

Learning LeaderJournal

A I I IFaculty Program Advocate CoachFacilitator htroductory

Organizational Mentors for Working Students Workshop

L

I

I

Create

I

I

Online support: Admin., Workshops, community Building1

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A

Feedback

Feedback

I

I

FIGURE 2. Leadershlp development: Generic deslgn.

8

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education forzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Businessopportunities for self-analysis, is based on the PROBE methodology developed by Nirenberg (1994). This method requires students to create a project that is completed at the end of their studies and uses classroom time to explore aspects of individual, team, and organizational behavior in action.

A T-group

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(or community) environ-ment is established. Part-time graduate students must participate in intensive on-campus residencies and, through extensive journal readings and with the help of organizational mentors in their work places, are expected to apply what they learn for testing their inter- personal effectiveness.

There are four supporting pieces to the development process, which gives each participant encouragement and sources of constructive feedback. First, a faculty-student committee plans and evaluates experiences, content focus, requirements, and outcomes. After an intensive initial residency, each partici- pant is paired with a peer coach who is a member of the cohort but not neces- sarily in the same study team. Each participant also has access to at least one faculty member, often the program advocate, as well as an organizational mentor in the case of part-timers. Finally, each student keeps a structured journal (see Nirenberg, 1998) that pro- vides a place both to reflect on lessons and experience and to keep responses to inquiries relating to the content of leadership.

Self

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Content

Mastering oneself

The content of leadership develop- ment programs is immense. Two general approaches are needed to accommodate younger, less experienced participants and older, more experienced ones. In

Figure 3, I present a general guide on

how experience influences the content focus and relevance to participants. Age and experience are not always the decid- ing factors. Along the left side of the fig- ure, I present the steps taken in a suc- cessful managerial career, from the entry level to top management. Corresponding to the loci of leadership are the major challenges that the learner will face. The right-hand column indicates learning

enhancements and the focus of practices

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

’

Organizational leadership8

4

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Teamleadershipds

1

.$

MasteringArticulating and committing to meaning

Establishing visionhission/ values Mastering interpersonal and SkillS Personal development and skill practice organizational

[image:5.612.224.567.33.285.2]Initial exposure to techniques, skills, language, and rationale of leadership and personal development

FIGURE 3. Leadership development.

The latest thinking from the disciplines from a practical, strategic perspective

Networking via site visits, case studies with peers, conferences

Techniquedpmtice:

To learn from each other how to expand methods of learning about leadership and one’s impact

New techniques learned and

tested on the job

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

in their placeof work

addressed in the leadership development program.

Each of the five levels of develop- ment, from mastering oneself to achiev- ing a legacy/purpose, requires students to analyze their own needs and goals within a traditional business framework of operations extending to top manager (locus of leadership). In such a pro- gram, existing nomenclature should be blended with that familiar to advanced leadership development at the graduate level to provide an easy transition. Within such a framework, faculty mem- bers may choose an appropriate depth of study in one or more of the five domains of leadership: intrapersonal, interpersonal, team, organizational, and societal. This approach is based on French and Bell’s (1990) intervention strategies for organizational develop- ment practitioners.

A definition of leadership must be established before it can be developed. Some schools of business closely align leadership development and manage- ment education, which results in defini- tions such as “the preparation that one receives in learning the content in an MBA program.” A graduate can assume a position in middle management and, presumably, supervise, manage, or lead whatever subordinates he or she is assigned. Leadership is simply the instrumental application of acquired knowledge.

Reporting on the conclusions of a longitudinal study (cited in Seligman,

2002, p. 164), the Aspen Institute stated

that “during the two years of business school, the surveyed students became more-not less-dedicated to the ‘importance of shareholder value.’” In such an environment, how is leadership defined? Is it merely the ability to have

subordinates perform well in the inter- ests of an unidentified “shareholder?” Does a lion tamer “lead” the lion through the burning hoop? In another view, based on the assumption that society values shareholder return as its prepotent purpose and relies on a hier- archical chain of command to hold human resources solely in service to that goal, leadership development becomes unnecessary or an exercise in

human alchemy. In this possibly cyni- cal definition, leadership means getting people to do what the leader wants them to do and liking it.

Leadership remains a concept about which everyone is an expert, but no two people define it quite the same way. A more contemporary definition of leader- ship includes the idea of choice by fol- lowers who are not just subordinataes. This view embraces the personal, informed, willingness to follow rather than merely comply; a consciousness of doing the right thing rather than just the expected thing; and the idea that there is a meaningful and worthwhile goal

September/October 2003 9

besides shareholder value toward which everyone is working. In this view, lead- ership signifies informed consent rather than a function dependent on possession of legitimate power bestowed by the

organization.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Taking Business Programs to a New Level

The

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MBA degree, as the flagship ofschools of business, has been under attack for some time. Such criticisms focus on curricular issues, such as the typical program’s increasing irrelevance

(Pfeffer

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Fong, 2002), as well as thefact that MBA programs do not offer

leadership development. If business schools are to remain credible sources of future business leaders, they must change immediately or see their market for leadership development turn to con- sultants and other schools.

By following these guidelines, administrators can encourage the cre- ation of substantive, credit-bearing lead- ership development programs in busi-

ness schools as

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an enhancement to theMBA degree. In this article, I proposed

a sample program that could lead to either a “major” focus, a stand-alone degree, or a parallel, substantial, but noncredit track that would help MBA

students become lifelong practitioners of leadership skills.

REFERENCES

Buss, D. (2001). When managing isn’t enough:

Nine ways to develop the leaders you need.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Wor!iforce, December, 44-48.

Charan, R., Drotter, S., & Noel, J. (2000). The

leadership pipeline: How to build the leader- ship powered company. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

Crawford, C. B., Brungardt, C. L., Scott, R. F. &

Gould, L. (2002). Graduate programs in organi- zational leadership. The Journal of Leadership

Studies, 8(4), 64-74.

Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership eflec-

tiveness. New York McGraw-Hill.

French, W., & Bell, C. H. (1990). Organization

development (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hambrick, D. C. (1994). 1993 Presidential address: What if the Academy actually mat- tered? Academy of Management Review, 19( I ) ,

Nirenberg, J. (1994). An introduction to PROBE: Practical organizational behavior education. 11-16.

Journal of Management Education, 18(3). 324-33 1.

Nirenberg, J. (1998). Integrating theory and expe- rience for working adult students through the

Learning Leader Journal. Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Leader-ship Studies, 5(3), 57-71.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The nature of managerial

work. New York: Harper and Row.

Mowday, R. T. (1997). Presidential address: Reaf- firming our scholarly values. Academy of Man-

agement Review, 22, 335-345.

Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R. I. (2000). The knowing

doing gap: How smart companies turn knowl- edge into action. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. (2002). The end of busi- ness schools? Less success than meets the eye.

Academy of Management Learning & Educa- tion, ](I), 78-95.

Porter, L. W., & McKibbin, L. E. (1988). Man-

agement education and development: Drift or thrust into the 21st century? New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rynes, S. L., Bartunek, J. M., & Daft, R. L. (2001). Across the great divide: Knowledge creation and transfer between practitioners and academics. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 340-355.

Seligman, D. (2002, October 28). Oxymoron 101.

Forbes, 160-164.

Tichy, N. M. (2002). The leadership engine: How

winning companies build leaders at every level.

New York: HarperBusiness.

Vroom, V. H. & Yetton, P. (1973). Leadership and

decision making. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

10 Journal of Education for Business