Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI

TANJUNGPINANG, KEPULAUAN RIAU] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:59

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Effect of Tuition and Opportunity Cost

on the Pursuit and Completion of a Graduate

Management Degree

Mark Montgomery & Irene Powell

To cite this article: Mark Montgomery & Irene Powell (2006) The Effect of Tuition and

Opportunity Cost on the Pursuit and Completion of a Graduate Management Degree, Journal of Education for Business, 81:4, 190-200, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.4.190-200

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.4.190-200

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 34

View related articles

he few studies that exist on the demand for graduate business education (Jantzen, 2000; Montgomery, 2002) have focused on the impact of tuition cost on the demand for a partic-ular institution. We examined the impact of the cost of obtaining a degree on one’s decision to enroll in a graduate management program, and on the likeli-hood of one completing a program once enrolled in it. In our analysis, we con-sidered more than just tuition cost. Tuition is only the explicitcost of pur-suing a graduate management degree. There is also a substantial implicit cost of lost earnings while attending school. The latter is usually called the opportu-nity cost of obtaining the degree. We considered two questions in this research: (a) How do the explicit and implicit costs influence the decision to pursue a management degree? and (b) how do these costs affect the likelihood of completing the degree? The cost effects were compared across demo-graphic groups and between more com-petitive and less comcom-petitive business schools. The data for this study came from a unique longitudinal survey con-ducted with registrants for the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT).

Review of the Literature

The research that is most relevant to the present study is that done on gradu-ate school attendance or completion

T

ABSTRACT. In this study, the authors

used multivariate statistical analysis to

examine the impact of cost on the

likeli-hood that a person will both enroll in and

complete a Master of Business

Administra-tion (MBA) program. They considered both

the explicitcost of paying tuition and the

implicit cost,or opportunity cost, of

earn-ings foregone while in school. Results

sug-gest that tuition is not a major impediment

to either pursuing or completing an MBA.

However, high opportunity cost tends to

reduce enrollment and degree completion.

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

decisions. The majority of those researchers focused only on determi-nants of matriculation (Eide, Brewer, & Ehrenberg, 1998; Fox, 1992; Weiler, 1994). In two studies (Baker, 1998; Ehrenberg & Mavros, 1995), the researchers investigated determinants of graduate school completion for samples of students who had already made the decision to attend. For example, Baker used a set of applicants for fellowships for science and engineering graduate school who all were going to attend their respective programs. Ehrenberg and Mavros used data on students already enrolled in graduate programs in four disciplines. By using data on stu-dents who have already made the deci-sion to attend, sample selection might result in biased estimates of the effects of factors, such as ability, gender, or race, on the probability of completion. For example, if ability is correlated with the probability of attendance—which it surely is—then the effect of ability on completion for the group of attendees will be biased. In addition, by using data only from students who were enrolled, earlier researchers could not take into account the effect of cost on the behav-iors of people who had abandoned plans to attend precisely because the costs were prohibitive. In the current study, we looked at such people.

The aforementioned researchers ana-lyzed attendance or completion in either

The Effect of Tuition and Opportunity Cost

on the Pursuit and Completion

of a Graduate Management Degree

MARK MONTGOMERY IRENE POWELL GRINNELL COLLEGE GRINNELL, IOWA

PhD programs or in both PhD and pro-fessional schools combined, but none considered business schools. They also used data on individual students. How-ever, Jantzen (2000) attempted to identi-fy the factors that influence the demand for U.S. graduate business programs using data on business schools and their enrollments. He found that enrollment at individual business schools was neg-atively affected by tuition costs and pos-itively affected by quality and being in a generally high-demand area. Even so, because Jantzen used data on schools, not individuals, he could say nothing about the effect of demographic charac-teristics on demand for business educa-tion, especially how they interact with costs. However, individual data provide insight on such issues, such as, showing whether minority students are more sen-sitive to costs than are White students.

In our research, we took advantage of a unique longitudinal survey of GMAT registrants to develop a multivariate sta-tistical analysis of a sequential set of decisions made by individuals who con-templated attending business school. We noted students’ choices among three enrollment alternatives: To pursue a Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree full time, part time, or not to pursue one at all. We also noted whether, having enrolled in an MBA program, students decided to complete the degree or drop out or were still pur-suing it at the time of the last interview. The methodology we used here, multi-variate analysis of sequential decisions, follows that of a small number of previ-ous studies in which researchers exam-ined college-level attendance and com-pletion (Ganderton & Santos, 1995; Light & Strayer, 2000, 2002; Venti & Wise, 1983). In particular, Light and Strayer (2002) used data on individual students and their schools to focus on the effect of race on college attendance and completion in a sequential choice model. Controlling for other variables, they found that minorities are more like-ly than Whites to attend college and more likely than observationally equiv-alent Whites to graduate from college. However, they found that the uncondi-tional likelihood of earning a degree is lower for Blacks than for Whites. This finding emphasizes the importance of

using a nested choice model to examine attendance and completion of graduate school programs. The GMAT registrant survey used in this study made it possi-ble to examine more carefully the effect of both the explicit andimplicit costs of obtaining an MBA degree on the proba-bility of attendance and completion as compared with previous studies.

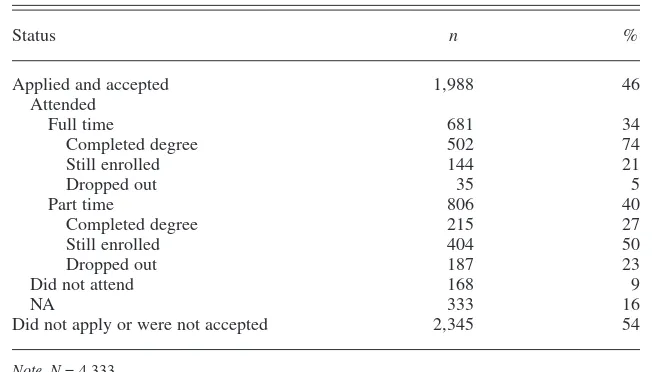

METHOD

In this study, we used the GMAT Reg-istrant Survey, sponsored by the Gradu-ate Management Admission Council, the organization that administers the GMAT. The Battelle Memorial Institute in Seat-tle, Washington, designed the survey instruments and collected the data. The survey involved individuals who regis-tered to take the GMAT on test dates between June 1990 and March 1991. The registrants were surveyed in three waves between 1991 and 1994. There were 4,333 registrants who completed all three waves of the survey. A large fraction of those interviewed never pur-sued graduate business education; many never even bothered to take the GMAT. In our study, we relied on a subsample of 1,988 GMAT registrants who applied to, and were accepted by, at least one grad-uate management program. Table 1 shows the proportion of sample mem-bers who applied to, attended, and com-pleted business school.

We supplemented data from the sur-vey questionnaire with information from the Graduate Management Admissions Council’s own registration and test records. We obtained information about sample members’ undergraduate schools from Barron’s Profiles of American Col-leges (1992). Finally, we took data on the characteristics of graduate business programs from Barron’s Guide to Grad-uate Business Schools (Miller, 1994).

Estimating the Cost of Attending Graduate Management School

Opportunity Cost Estimates

The explicit cost of going to business school (the tuition) understandably might have a direct effect on one’s deci-sion to attend school; however, the the-oretical effect of opportunity cost is slightly subtler. The key element in opportunity cost is the income foregone through lost earnings. There are several ways in which going to graduate school reduces earnings. Most obviously, of course, it is quite difficult to be a full-time student while trying to hold down a full-time job. However, the majority of graduate management students do not attend full time; many pursue the degree while working a regular job. Even so, there are still opportunity costs. To the extent that more time devoted to the job translates into promotion and pay raises,

TABLE 1. Outcomes of Business School Application and Attendance for Those Involved in Completing the Graduate Management Admission Registrant Survey

Status n %

Applied and accepted 1,988 46

Attended

Full time 681 34

Completed degree 502 74

Still enrolled 144 21

Dropped out 35 5

Part time 806 40

Completed degree 215 27

Still enrolled 404 50

Dropped out 187 23

Did not attend 168 9

NA 333 16

Did not apply or were not accepted 2,345 54

Note. N= 4,333.

even part-time students may lag behind coworkers who are unencumbered by classes, exams, and homework. More-over, the decision to take night classes can constrain the kind of day job avail-able to the student.

Opportunity cost is difficult to mea-sure. It cannot be observed directly, like salary or income, because it involves an alternative that the student did not choose. Therefore, it is necessary to pre-dict opportunity cost. This is done using the standard econometric technique of estimating a multivariate regression equation that relates earnings to individ-ual characteristics, such as education, work experience, race, and gender. We used regression analysis to relate earn-ings to personal characteristics for full-time students, part-full-time students, and those who were not in school. By esti-mating that relationship, it was possible to predict what a given person would earn in the job market from observing what similar people tended to earn.

In most studies that involve predicted earnings, researchers have to estimate the wage equations with the same sam-ple to which the coefficients are applied. However, we were able to avoid this by taking advantage of the 1986 MBA New Matriculants Survey conducted by the National Opinion Research Center of the University of Chicago and also sponsored by the Graduate Manage-ment Admission Council. Regressions from the New Matriculants Survey pro-vided earnings coefficients that we then applied to the individual characteristics

of respondents to the GMAT survey to predict earnings for GMAT registrants. The predicted earnings created by applying the regression coefficients to the GMAT survey data represent our measures of opportunity cost.

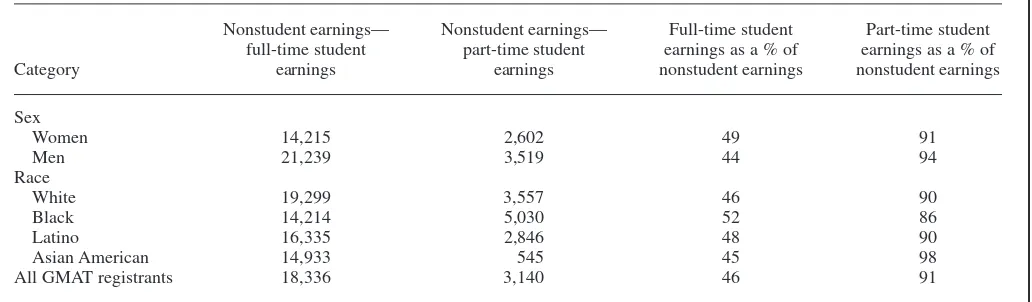

Table 2 shows the predicted opportu-nity cost for full-time and part-time study. To attend graduate management school, a full-time student sacrifices more than $18,000 per year (in 1994 dollars). This represents about 56% loss of income when compared with what the person could expect if not in busi-ness school. Part-timers sacrifice much less, about $3,000 per year, or roughly 9% of what they would be earning if not a business school student. Average opportunity cost varies considerably by sex. Full-time management school costs men $21,239 in earnings versus $14,215 for women. However, because women earn less in the job market, their pro-portionate sacrifice is much closer to men’s: 51% of nonstudent earnings compared with 56% for men. Compar-ing by race and ethnicity, Whites sacri-fice more, in absolute dollars, than Blacks, Latinos, or Asian Americans do, to attend full time. However, in propor-tionate terms, Blacks have the highest opportunity cost of full-time attendance, but the lowest opportunity cost of part-time attendance.

Tuition Cost Estimates

To estimate tuition and financial aid, we found tuition cost for each individ-ual averaged over the schools for

which each was accepted for admis-sion. The cost per credit hour was esti-mated from figures reported in Bar-ron’s Guide to Graduate Business Schools (Miller, 1994). We then multi-plied the cost per credit hour times the minimum number of credits required for a degree. For schools that reported only annual tuition, we multiplied annual tuition times the number of years required to obtain a degree. We similarly used the average financial aid award for each school to measure the effect of financial aid.

Table 3 shows that full-time costs are slightly lower on average than part-time costs: $10,838 versus $12,195. Why are part-time costs higher on average than are full-time costs? One possible expla-nation is that demand for full-time slots is more elastic than demand for part-time slots and, therefore, full-part-time slots have a lower equilibrium price (this is consistent with the observation that part-time attendance is by far the most popular choice).

Estimating Predicted Effects of Cost on Graduate Management School Attendance and

Completion

To obtain estimates of the effect of cost on the probability of attending graduate management school and the probability of completing school, we estimated multinomial logit models by maximum likelihood. Table 4 shows the variables included in the models

TABLE 2. Mean Opportunity Cost of Attending a Graduate Management Program Full Time and Part Time, by Sex and Race Compared With All Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) Registrants

Nonstudent earnings— Nonstudent earnings— Full-time student Part-time student

full-time student part-time student earnings as a % of earnings as a % of

Category earnings earnings nonstudent earnings nonstudent earnings

Sex

Women 14,215 2,602 49 91

Men 21,239 3,519 44 94

Race

White 19,299 3,557 46 90

Black 14,214 5,030 52 86

Latino 16,335 2,846 48 90

Asian American 14,933 545 45 98

All GMAT registrants 18,336 3,140 46 91

Note. 1994 earnings presented in current dollars as predicted from regression models.

along with the mean values for the sample.

Using these variables, we first esti-mated the effect of cost on the decision

to attend graduate management school and the effect on the probability of com-pleting a graduate management degree conditional upon having pursued one.

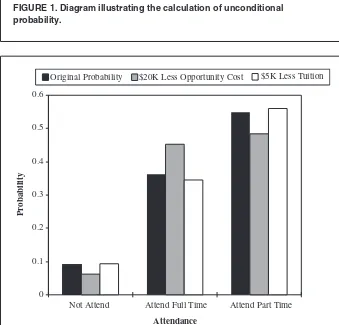

We next combined those estimates to predict the effect of cost on the uncon-ditional probability of completing a management degree. That is, on the probability of both entering a degree program and completing it. To do this, we estimated models of completion that were conditionalupon attending school part time or full time. We then multi-plied the probabilities from these mod-els by the probability of attending in the relevant way—part time or full time. From the products of attendance and the conditional completion probabilities, we could estimate the unconditional likelihood of a particular outcome like completing or dropping out.

Figure 1 shows a simple schematic for this calculation. The boxes on the left-hand side represent probabilities of attending part time, full time, or not at all, respectively.

The boxes in the middle represent probabilities of completing conditional on part-time or full-time attendance. If we multiply the left and center probabil-ities, we can sum over outcomes (boxes of the same shade) to get unconditional probabilities (the boxes on the right).

RESULTS

Effect of Cost on Probability of Attendance and Conditional Completion

Figures 2 and 3 show the predicted effect of changes in opportunity cost and tuition cost on the probability of

TABLE 3. Mean Tuition, Financial Aid, and Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) Scores at Business Schools Where GMAT Registrants Were Accepted, by Sex and Race Compared With All GMAT Registrantsa

Tuition cost of obtaining Tuition cost of obtaining

degree by attending degree by attending Average financial

Category full time ($) part time ($) aid award ($) Average GMAT score

Sex

Women 10,569 11,985 6,478 542

Men 11,028 12,343 7,014 549

Race

White 10,841 12,337 6,816 545

Black 12,063 12,848 4,067 551

Latino 10,090 10,924 6,511 551

Asian American 11,951 13,235 7,068 545

All GMAT registrants 10,838 12,195 6,788 546

aFrom Miller (1994).

TABLE 4. Variables Included in the Statistical Models

Variable M %

Demographic characteristics

Age 27

Race/Ethnicity

Black 16

Asian American 10

Latino 17

Married (yes) 36

Number of kids at home 0.35

Work experiencea

1–3 Years 31

3–7 Years 27

> 7 Years 23

Undergraduate education Degree

BA in humanities 8

BA in science 26

BA in social science 15

GMAT score 508

% of sample from a less selective BA school 37

Undergraduate grade point average (4-point scale) 3.06

Graduate educationb

School with GMAT cutoff score > 650 11

School with GMAT cutoff score 600–650 25

School with GMAT cutoff score 500–600 45

Cost measures

Tuition to obtain degree full timec $10,471

Tuition to obtain degree part timec $11,352

Predicted earnings if not in school $34,895

Note. Estimation sample differs from that in Table 3 because of some missing variables. aBefore taking Graduate Management Admission Test. bThese are for the management school attended, not included in the attendance models. cFor those not attending this was measured for their first choice school.

expected direction; lowering the implic-it cost of attendance by lowering oppor-tunity cost tends to encourage a shift toward full-time attendance. The disin-centive to stay out of full-time school seems to be slightly reduced. The prob-ability of not going to school drops from about .09 to .07. There is a somewhat larger migration from part-time to full-time attendance; the probability of going part time drops from .55 to .48. The combination of these influences is that reducing nonstudent earnings by $20,000 would increase the proportion of full-time students from .37 to .45, a small but nontrivial effect.

The third set of columns in Figure 2 represents the effect of a reduction in explicit cost, or a reduction in tuition cost. In contrast to other studies on busi-ness schools (Jantzen, 2000) and on col-lege attendance decisions (Ganderton & Santos, 1995), these results suggest a small impact. A $5,000 dollar tuition reduction (about half the average cost) appears to have minimal influence on the attendance decision.

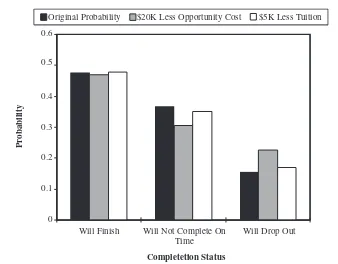

Figure 3 shows the effect of a reduc-tion in cost on the probability of com-pleting a degree for those students who matriculatedin a graduate management program sometime during the survey period. Here, the predicted effects of opportunity cost are somewhat surpris-ing. Note from the right-hand side of the figure that loweropportunity cost tends to increase the probability of dropping out. The probability of quitting the pro-gram rose from about .16 to about .23. This increase in dropouts appears to come at the expense of those who stay in, but have not finished, rather than those who finish. In other words, lower job earnings tend to convert some of those who take a relatively longer time to earn their degrees into dropouts. It does not seem to affect those who get their degrees relatively more expeditiously.

This result may seem counterintu-itive. One would expect those with rela-tively low forgone earnings to be less likely to drop out and to be more willing to keep plugging along in school because they are sacrificing relatively less by being there. There are two potential explanations. The first is that this result—that low earners are more likely to drop out—is an artifact of the attending graduate management school

and of completing a degree once enrolled, respectively. We considered two scenarios. In Scenario 1, we assumed that nonstudent earnings, our measure of opportunity cost in the sta-tistical model, drops by $20,000 per annum. In Scenario 2, the tuition cost of

obtaining a degree drops by $5,000. Each of these values represents roughly half of the average level of earnings or tuition, respectively, for the average sample member.

Figure 2 shows the impact of these changes on attendance. The effect of the change in opportunity cost is in the Probability of

Attending

FIGURE 1. Diagram illustrating the calculation of unconditional probability.

Did Not Start

Completed Full Time

Still Attending Full Time

Quit Full Time

Still Attending Part Time

Quit Part Time Did Not

Attend

Attended Full Time

Attended Part Time

Unconditional Probability of Completing Conditional Probablity

of Completing

(Boxes of same shade are added together)

Completed Degree

Still Working Toward Degree

Not a Degree Candidate Completed Part Time

FIGURE 2. Estimated effect of opportunity cost on the decision to attend graduate management school, 1991–1994.n= 1555.

Not Attend 0.6

Pr

obability

Original Probability

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Attend Full Time Attend Part Time

Attendance

$20K Less Opportunity Cost $5K Less Tuition

ate management degree conditional upon having pursued one. In Figure 4, we combined the estimates in Figures 2 and 3 to predict the effect of opportunity cost on the unconditional probability of com-pleting a management degree (i.e., the probability of both entering a degree pro-gram and completing it).

Lowering opportunity cost appears to substantially improve the likelihood of obtaining a degree (in a given time peri-od) from about .24 to .40 (see Figure 4). It also reduces the chances of still being enrolled and increases the chances of dropping out. However, given the way in which we calculated the uncondition-al probabilities, they may not add up to one. Given the results in Figures 2 and 3, the implication of Figure 4 is that opportunity cost reduces the uncondi-tional expected completion rate by shift-ing some potential full-timers into part-time programs or by causing some students to delay entry into school. Also, with high opportunity cost, more people choose not to be candidates for the degree. This finding is consistent with the expectation that opportunity cost discourages attendance, particularly among less motivated students.

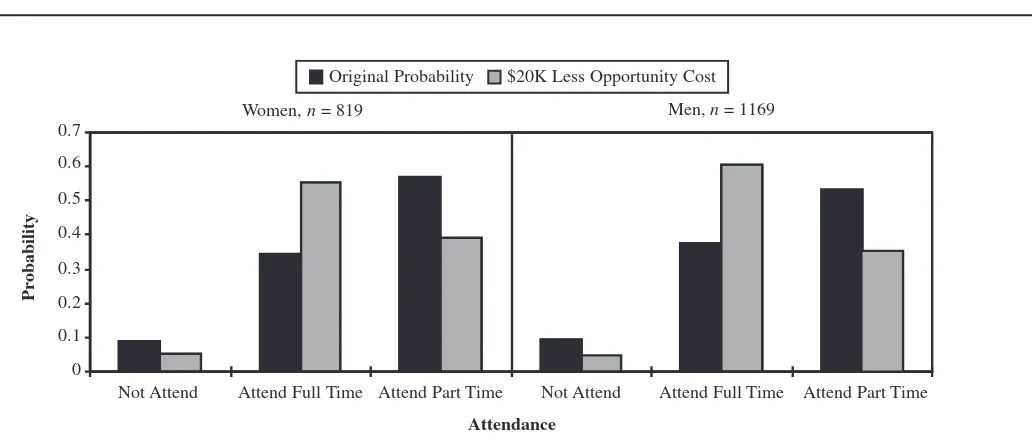

The Effect of Opportunity Cost by Sex, Race, and Part-Time or Full-Time Status

Next, we examined whether and how the effect of opportunity cost varies among students of different race, gen-der, or full-time or part-time status. Fig-ure 5 shows the effect of opportunity cost for women compared with men. The differences between men and women appear to be very small; for both sexes, lowering opportunity cost increases the proportion of full-timers, mainly at the expense of part-timers. The effect for men is slightly larger. It is interesting to note that, when we segre-gate the sexes, both models predict a larger effect of opportunity cost than did the joint model for the two sexes. This is because the joint model imposes the restriction that all variables have the same effect for men and women, an assumption that may be too restrictive. Figure 6 shows differences between two aggregate racial groups: (a) Blacks and Latinos, and (b) Whites and Asian way we have measured completion. For

our study, completing a degree means completing it within the 4 years of our survey period. It is possible that our higher earners are less likely to have dropped out by the time of the second follow-up interview. If higher earnings cause them to postpone entering man-agement school, it could appear that those with high opportunity cost drop out less frequently. In this case, among the lower earners we would observe more students who have been in school long enough to know they do not want to continue.

A second potential explanation for why low nonstudent earnings increase the drop-out rate is that opportunity cost is likely to act as a screen. Some stu-dents are more motivated than others to work hard and to complete management school. Presumably, those with lower motivation are more likely to quit, but they are also less likely to enroll in the first place. It is plausible that high opportunity cost keeps less motivated students out of business school and therefore, indirectly reduces the quit rate. For example, one can imagine some low earners, especially those who

are not employed, attending school because they have little else to do. Such low incentive may not sustain them through a rigorous graduate program, so they would more likely drop out. This view is consistent with our finding that lower earnings donotincrease the pro-portion that completes the degree. Those who finish in a timely fashion are presumably more highly motivated than those who do not (especially those who attend full time) and higher opportunity costs do not tempt the highly motivated students to drop out of school.

In contrast to previous studies on graduate school completion (Ehrenberg & Mavros, 1995) and college comple-tion (Light & Strayer, 2000), Figure 3 suggests that tuition appears to have lit-tle impact on the completion rate. This is consistent with the attendance results.

Effect of Cost on Unconditional Completion

Figure 2 shows the estimated effect of opportunity cost on the decision to attend graduate management school; Figure 3 considers the effect of opportunity cost on the probability of completing a gradu-0.6

FIGURE 3. Effect of opportunity cost on the probability of completing a graduate management degree conditional upon having pursued one, 1991–1994.n= 1487.

Will Finish

Pr

obability

0

Will Not Complete On Time

Will Drop Out

Completetion Status

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost $5K Less Tuition

Americans (many empirical studies suggest similar labor market behavior and results for Blacks and Latinos and for Whites and Asian Americans). Between races, the effect of opportunity cost has a similar pattern but the magni-tude varies somewhat. For Whites,

lower opportunity cost shifts a larger fraction of students into full-time atten-dance (a proportion of about .2 as opposed to .12 for Blacks and Latinos). Moreover, for Blacks and Latinos, lower opportunity cost increases full-time attendance by pulling more people

from the “not attend” category and less from the “attending part time” category than occurs with Whites. Apparently, higher opportunity cost tends to dis-courage proportionately more minority candidates from pursuing graduate busi-ness education than it does for White students.

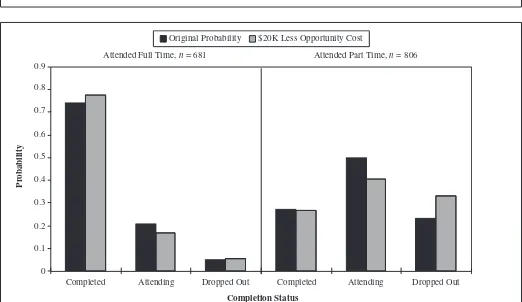

Figures 7–9 show the predictions for completion, differentiated by part-time or full-time status (Figure 7), by sex (Figure 8), and by race (Figure 9). Note that, as in Figure 2, these completion rates are conditional upon having enrolled in a program. Figure 7 shows that opportunity cost affects full- and part-time students in somewhat differ-ent ways. In both cases, opportunity cost moves a relatively small propor-tion of people out of the category of “still attending.” Among full-timers, these people tend to finish whereas, among part-timers, they tend to drop out. This finding reinforces our earlier interpretation of the impact of opportu-nity cost on completion: it acts partly as a screen. Surely less motivated students will disproportionately attend part time, so a screening effect should be more noticeable among part-timers. Indeed, among the full-timers, higher opportu-nity cost has virtually no effect on the dropout rate.

As with the attendance models, the impact of opportunity cost on comple-tion seems to be noticeably different. For both racial groups, lowering

oppor-FIGURE 4. Effect of opportunity cost on the unconditional probability of completing a management degree, 1991–1994.n= 1988.

Completed Degree 0.5

Pr

obability

0.45

0.4

0.35

0.3

0.25

0

Working Toward Degree

Not a Degree Candidate

Degree Status

0.2

0.15

0.1

0.05

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost

FIGURE 5. Effect of opportunity cost of attendance, by sex: 1991–1994.

Not Attend

Pr

obability

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

Attend Full Time Attend Part Time

Attendance

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Not Attend Attend Full Time Attend Part Time

Women,n= 819 Men,n= 1169

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost

FIGURE 6. Effect of opportunity cost of attendance, by race: 1991–1994.

Not Attend

Pr

obability

0.6

0.5

0.4

Attend Full Time Attend Part Time

Attendance

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Not Attend Attend Full Time Attend Part Time

Black and Latino,n= 352 White and Asian American,n= 1636

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost

FIGURE 7. Effect of opportunity cost on completion of degree, by part- or full-time status: 1991–1994.

Completed

Pr

obability

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

Attending Dropped Out

Completion Status

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Completed Attending Dropped Out

0.5

0.4

Attended Full Time,n= 681 Attended Part Time,n= 806

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost

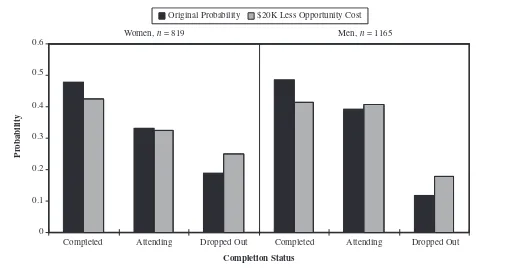

tunity cost increases drop-out rates, which differ very little between the

sexes (Figure 8). However, with race (Figure 9), the effects are

proportionate-ly greater for minorities. For Whites and Asian Americans, opportunity cost also

FIGURE 8. Effect of opportunity cost on completion of degree, by sex.

Completed

Pr

obability

0.6

Attending Dropped Out

Completion Status

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Completed Attending Dropped Out

0.5

0.4

Women,n= 819 Men,n= 1165

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost

FIGURE 9. Effect of opportunity cost on completion of degree, by race.

Completed

Pr

obability

0.6

Attending Dropped Out

Completion Status

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Completed Attending Dropped Out

0.5

0.4

Black and Latino,n= 352 White and Asian American,n= 1636

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost

tends to increase the probability of com-pleting the degree versus still being in school. For other minorities, the effect is reversed. Thus, for Blacks and Lati-nos, higher earnings tend to discourage completion, partly by extending their length of study, but more significantly by increasing their quit rate.

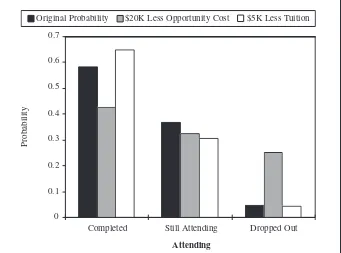

The Effect of Cost at Top-Tier Schools

Our final set of figures, Figures 10 and 11, show the influence of opportunity cost and tuition at top-tier and second-tier business programs, respectively. Schools are ranked on the basis of competitive-ness of admissions. We used a variable developed by the Batelle Memorial Insti-tute that reflects the minimum acceptable GMAT score for a person to be admitted to the program in question. Using this GMAT-cutoff criterion, schools were divided into four categories as indicated in Table 4. It is clear from the tables that schools that are more selective tend to charge higher tuition—indeed, substan-tially higher tuition. For the average reg-istrant, tuition at a top-tier school (GMAT cutoff score > 650) was nearly three times that at a lowest-tier school (GMAT cutoff score < 500). Students at the top-tier schools also faced higher opportunity cost, presumably because the superior credentials and abilities required for acceptance by the top business school are also rewarded in the job market.

Because elite schools are more expen-sive, in Figures 10 and 11 we used a much larger decrement to tuition than we used in Figure 2 ($20,000 compared with the $5,000 in the earlier figure). The figure shows that even this very large change in tuition cost has a fairly small impact on the likelihood of finishing a degree at an elite school. Lower tuition raises the com-pletion rate at the top schools by only about .06 (see Figure 10). At second-tier institutions, the predicted completion rate actually falls slightly with lower tuition (see Figure 11). The most noticeable effect in Figures 10 and 11 is that of opportunity cost on completion at the highest ranked schools. Decreasing opportunity cost raises the drop-out rate very sharply, from .05 to .25 (Figure 10). Most of the extra dropouts are shifted over from completers (rather than those still enrolled). As before, we attribute this

find-ing to the tendency of earnfind-ings to screen out degree aspirants who are not highly motivated. The effect appears to be even stronger at elite institutions, where the rigor of the program might be particularly discouraging to less motivated students.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we examined the effect of both tuition and opportunity cost on the decision to attend graduate manage-ment school and, for those who

attend-FIGURE 10. The effect of changes in cost on completion of degree, by rank of graduate school. Top Tier Schools (Graduate Management Admission Test cutoff score > 650).n= 175

Completed 0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Still Attending Dropped Out

Attending

0.7

Probability

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost $5K Less Tuition

FIGURE 11. The effect of changes in cost on completion of degree, by rank of graduate school. Second tier schools (Graduate Management Admission Test cutoff score 600–650).n= 364.

Completed 0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Still Attending Dropped Out

Completion Status

Pr

obability

0.7

Original Probability $20K Less Opportunity Cost $20K Less Tuition

ed, on the probability of completing a degree within a given time period. One important caveat should be stated regarding these results. We directed our survey only at people who registered to take the GMAT. This limits our ability to observe the extent to which tuition or opportunity cost discourage, attendance in a broader population. Because they registered for the GMAT, we can pre-sume that our sample members all seri-ously considered graduate management school. It is quite conceivable that other people were sufficiently discouraged by opportunity cost or tuition and that they never seriously contemplated business school. Such people would never show up in our sample. Our results, therefore, could understate the influence of cost on the decision to pursue a business degree.

The statistical models yielded several interesting results. First, tuition is not a major impediment to either attending management school or completing a degree. This is true even at elite institu-tions where tuition costs are much high-er than avhigh-erage.

A more substantial impediment to get-ting an MBA (within a fixed period of time) appears to be the implicit cost of forgone earnings while in school. These opportunity costs seem to operate in three ways to delay or forestall comple-tion of a degree. First, opportunity cost seems to have a small tendency to dis-courage attendance. Second, high oppor-tunity cost shifts a modest proportion of students from full-time to part-time attendance, thus slowing down comple-tion of the degree within any given time frame. Third, high opportunity cost low-ers rather than raises the drop-out rate among those who enroll in a degree pro-gram. We hypothesize that it does this by acting as a screen and discouraging

stu-dents with low motivation from entering programs. This screening effect appears most pronounced at the elite institutions.

The impacts of tuition and opportuni-ty cost do not vary greatly by gender. However, higher opportunity cost tends to discourage proportionately more minority candidates than White students from pursuing graduate business educa-tion. Also, the screening effect of oppor-tunity cost appears more pronounced among Blacks and Latinos. For these minority students, higher earnings seem to discourage completion, partly by extending their length of study, but more so by increasing their quit rate.

What are the implications of these findings for policy toward graduate man-agement education? One is that dollars invested in financial aid may have less impact on student enrollment and com-pletion than was previously believed. A second is that schools need to recognize the power of forgone earnings as an inhibitor of enrollment and completion. Schools would be wise to find ways to mitigate the earnings loss for part-time students. More flexible class schedules may be one example of a way to accom-modate the part-time student. Also, for an elite school, it may be worth ensuring that the night (i.e., part-time) program is not a poor cousin of the day (i.e., full-time) program. Also, understanding the effect of opportunity cost is especially important because it is likely that the most talented students are the ones with the highest potential earnings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Jason Bent for valu-able research assistance and to Mary Kay Dugan and Mark Gritz for helpful suggestions. This study was supported by the Battelle Memorial Institute in Seattle, Washington, and by a grant from the Grinnell College Faculty Grant Board.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Mark Montgomery, Department of Economics, Grinnell College, Grinnell, IA 50112.

E-mail: MONTGOME@Grinnell.edu

REFERENCES

Baker, J. G. (1998). Gender, race, and PhD com-pletion in natural science and engineering. Eco-nomics of Education Review, 17,179–188.

Barron’s profiles of American colleges: Descrip-tions of the colleges.(1992). Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series, 19.

Ehrenberg, R., & Mavros, P. (1995). Do doctoral students’ financial support patterns affect their times-to-degree and completion probability?

Journal of Human Resources, 30, 581–609. Eide, E., Brewer, D. J., & Ehrenberg, R. (1998).

Does it pay to attend an elite private college? Evidence on the effects of undergraduate col-lege quality on graduate school attendance.

Economics of Education Review, 17, 371–376. Fox, M. (1992). Student debt and enrollment in

graduate and professional school. Applied Eco-nomics, 24, 669–677.

Ganderton, P., & Santos, R. (1995). Hispanic col-lege attendance and completion: Evidence from the high school and beyond surveys. Economics of Education Review, 14, 35–46.

Jantzen, R. H. (2000). Price and quality effects on the demand for U.S. business programs. Inter-national Advances in Economic Research, 6, 730–740.

Light, A., & Strayer, W. (2000). Determinants of college completion: School quality or student ability? Journal of Human Resources, 35, 299–332.

Light, A., & Strayer, W. (2002). From Bakke to Hopwood: Does race affect college attendance and completion? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 34–44.

Miller, E. (1994). Barron’s Guide to Graduate Business Schools. New York: Barron’s Educa-tional Series. Inc.

Montgomery, M. (2002). A nested-logit model of choice of a graduate business school. The Eco-nomics of Education Review, 21,401–521. Venti, S. F., & Wise, D. A. (1983). Individual

attributes and self-selection of higher educa-tion: College attendance versus college comple-tion. Journal of Public Economics, 21, 1–32. Weiler, W. C. (1994). Expectations, undergraduate

debt and the decision to attend graduate school: A simultaneous model of student choice. Eco-nomics of Education Review, 13, 29–41.