Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 22:51

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Emotional Awareness and Emotional Intelligence

in Leadership Teaching

Neal M. Ashkanasy & Marie T. Dasborough

To cite this article: Neal M. Ashkanasy & Marie T. Dasborough (2003) Emotional Awareness and Emotional Intelligence in Leadership Teaching, Journal of Education for Business, 79:1, 18-22, DOI: 10.1080/08832320309599082

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320309599082

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 624

View related articles

Emotional Awareness and

Emotional Intelligence in

Leaders hip Teachina

NEAL M. ASHKANASY

MARIE T. DASBOROUGH

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

University

of Queensland

Brisbane,

Queensland,Australia

ver recent years, emotions, and

0

the concept of emotional intelli-gence in particular, have become promi- nent in organizational behavior litera-

ture (Ashkanasy &

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Daus, 2002; Brief &Weiss, 2002). In this article, we describe how this research has been incorporated into an undergraduate leadership course. In our study, we use Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) definition

of emotional intelligence:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

perception,assimilation, understanding, and man-

agement

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of emotions. Emotions in OrganizationalBehavior

Although organizational behavior researchers have become interested in the study of emotions relatively recent- ly, this interest has accelerated dramati- cally in the last few years. Barsade, Brief, and Spataro (2003, p. 3) have gone so far as to declare that this inves- tigation represents an “affective revolu- tion in organizational behavior” and even a “paradigm shift.” Nonetheless, although emotion has always formed a central component of working life (see Mastenbroeck, 2000 for a comprehen- sive history), the revolution had a slow

start (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1995).

The first major instigator was Arlie Hochschild (1983), who introduced the concepts of emotional labor and emo-

ABSTRACT.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Recent research hashighlighted the importance of emo- tional awareness and emotional intelli- gence in organizations, and these top- ics are attracting increasing attention.

In this article, the authors present the results of a preliminary classroom study in which emotion concepts were incorporated into an undergraduate leadership course. In the study, stu-

dents completed self-report and ability tests of emotional intelligence. The

test results were compared with stu- dents’ interest in emotions and their performance in the course assessment. Results showed that interest in and knowledge of emotional intelligence predicted team performance, whereas individual performance was related to emotional intelligence.

tional work. These ideas soon migrated to organizational behavior, largely through a conceptual review authored by Rafaeli and Sutton (1989), which identi- fied emotional expression as an impor- tant phenomenon in organizational research. Indeed, many of the early advances in the field were actually in sociology, especially in critical and fem- inist literature. For instance, Van Maanen and Kunda (1989) cast organizational life essentially as a process of emotion man-

agement, whereas Mumby and Putnam

(1992) introduced the idea of “bounded emotionality” as a foil for Simon’s (1 976) concept of “bounded rationality.” The more recent upsurge of interest, however, was initiated by Fineman’s

(1993) book Emotions in Organizations and influential articles such as those by the following authors: Isen and Baron (1991), who argued for the role of posi-

tive affect (see also Staw, Sutton, &

Pelled, 1994); Pekrun and Frese (1992),

who provided an overview of emotions

research in organizations; Ashforth and Humphrey (1993, who argued that more attention should be paid to emotions in organizational studies; George and Brief (1996), who introduced a theory of the role of mood in motivation; and Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), who posited Affective Events Theory. At around the same time, researchers in social and per- sonality psychology were resuming inter- est in this field (Damasio, 1994). Also in this period, Salovey and Mayer (1990) introduced the notion of emotional intel- ligence, which subsequently was popu- larized by Goleman (1995,1998).

Research productivity on the topic of emotions and emotional intelligence began to flower in the new century and included edited books (Ashkanasy, H%-

tel, & Zerbe, 2000; Ashkanasy, Zerbe,

& Hiirtel, 2002; Fineman, 2000; Lord,

Klimoski, & Kanfer, 2002; Payne &

Cooper, 2001) and special issues of

such journals as the Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Organi-zational Behavior (Fisher & Ashkanasy, 2000), Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Processes (Weiss, 2001), Human Resource Management

Review

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Fox, 2002), Leadership Quar-terly (Humphrey, 2002), and Motivation

and Emotion (Weiss, 2002). Significant-

ly, the Annual Review

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Psychologyincluded a chapter on the topic by Brief and Weiss (2002), and Ashkanasy, H&- tel, and Daus (2002) included an up-to-

date review in the Journal of Manage-

ment’s annual review issue.

In summary, emotions are now firmly on the agenda for research in organiza- tional behavior (OB). For instance,

Emonet

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(http:llwww.uq.edu.au/emonetf),an e-mail network for discussion of emo- tions in organizational settings, has over 400 subscribers worldwide and conducts biannual conferences on the topic. The results of this activity are now beginning to receive coverage in OB textbooks (Robbins, 2001), and Fineman (2003) recently has released the first textbook dedicated to emotions at work. In this article, we describe an application of this research in the teaching of an undergrad- uate leadership course.

In the specific instance of emotions and leadership, Humphrey (2002) argued that leadership is intrinsically an emo- tional process through which leaders rec- ognize employees’ emotional states, attempt to evoke emotions in employees, and then seek to manage employees’ emotional states accordingly (see also

Ashforth

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Humphrey, 1995; Ashkanasy& Tse, 2000). For example, in a laborato-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ry

study Lewis (2000) found that leadersexpressing anger toward their employees provoked feelings of nervousness and fear. Similarly, George (2000) described how leaders displaying feelings of excite- ment, energy, and enthusiasm aroused

similar feelings in their employees.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Emotional Intelligence

Concomitant with the growing atten- tion to emotions in organizations over the last decade, interest in emotional intelligence has been increasing. Mayer and Salovey (1997) defined emotional intelligence (EI) as compris- ing four branches: “the ability to per- ceive emotions, to access and generate

emotions so as to assist thought, to

understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth” (p. 5). The

study of emotional intelligence is not without controversy, however (Becker,

2003; Davies, Stankov, & Roberts,

1998). It has been defended by Jordan, Ashkanasy, and HSirtel (2003) as still being in a developmental stage. The concept also has proved extremely popular among practitioners, as evi- denced by Goleman’s (1995, 1998) best-selling books. Indeed, much of the criticism leveled at the study of EI derives from its very popularity, and sometimes uncritical promotion (Gole- man, 2000). Nonetheless, serious scholars are continuing to develop and validate measures of EI, including abil- ity measures such as the Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso Emotional Intelli- gence Test (MSCEIT; see Mayer, Caru-

so, Salovey, & Sitarenios, 2003) and

self/peer report measures (Jordan,

Ashkanasy, HSirtel, & Hooper, 2002;

Wong & Law, 2002).

Emotional intelligence has been addressed in the context of leadership by several researchers, including the present authors (Ashkanasy, 2003; Ashkanasy,

Hiirtel, & Daus, 2002; Ashkanasy & Tse;

2000; Dasborough & Ashkanasy, 2002;

George, 2000; Goleman, 1998, 2000). The general assumption of these authors is that leaders with high EI are better able to manage employee emotions to facili- tate employee performance effectively, although Dasborough and Ashkanasy (2002) have noted that EI also can be abused by manipulative leaders. Never- theless, authors such as Ashkanasy and Tse (2000), Friedman, Riggio, and Casella (1988), and George (2000) have linked EI to positive transformational and charismatic leadership. As an illus- tration of this, Wong and Law (2002) found that the emotional intelligence of leaders was associated with increased employee job satisfaction and “extra- role” behaviors. Finally, Ashkanasy (2003) and Wolff, Pescosolido, and Druskat (2002) have stressed EI as a fac- tor in emergent leadership in work teams.

A Study of Emotional Awareness and Emotional Intelligence in Leaders hip Teaching

The study that we discuss in this arti- cle was undertaken in the context of an undergraduate course titled “Leading

and Managing People” at an Australian university. The course was designed to help students appreciate the need for advanced leadership skills in the mod- em work place. Students were intro- duced to the idea that, in the constantly changing and knowledge-based busi- ness world, organizations are likely to depend more on leadership than on technology skills. The class was based on fundamental leadership concepts and their incorporation into practice and continuous self-reflection to produce “double-loop learning” (Argyris, 1994). Relying on Wong and Law (2002) and

Ashkanasy and Tse (2000), we predicted

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

that those students with high EI would perform better in a leadership course than those who scored low on this construct. Furthermore, we expected that this situa- tion would occur to a larger degree with respect to students’ teamwork, because emotional skills are required for leader- ship emergence within self-managing

teams (Wolff, Pescosolido, & Druskat,

2002) and are associated with higher lev- els of team performance (Steiner, 1972).

Method

During each week of the course, stu- dents were introduced progressively to leadership skills and concepts in lec- tures and participated in exercises that reinforced learning. We addressed the topic of emotional intelligence early in the course, at which point students com- pleted the Wong and Law (2002) self- report measure. Following this, we gave participants a user ID and password to enable them to complete the MSCEIT, if they wished, in their own time. We presented the test results to the students the following week, after which they learned about charismatic leadership and how charismatic leaders influence their followers through emotional tools. Later in the semester, students again were made aware of how leaders need to manage emotions during times of orga-

nizational change (Fox & Amichai-

Hamburger, 200 1 ; Huy, 2002).

Sample f o r Study

Participants were 144 second-year undergraduate students at an Australian university. Their ages ranged from

17-42 years

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(m =zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

22 years); 55% were female; and the ethnic composition wasAustralian (59%), Asian (24%), Euro-

pean (lo%), and “other” (7%). The class

had an average of 1.4 years full-time and

3.1 years part-time work experience.

Data Collection and Measures

Participants completed two measures of EI. The first was a self-report emo- tional intelligence survey developed by Wong and Law (2002). This instrument consists of 16 items based on the four- branch Mayer and Salovey (1997) model. Wong and Law reported an alpha of .94. The second measure was a Web-

administered version of the MSCEIT, an ability-based test of EI (Mayer, Caruso,

Salovey, & Sitarenious, 2003).

Assessment of Leadership Training

Course assessment comprised two in- semester assignments and a final exam- ination. The first assignment was the Leadership Training Package (LTP), a 12,000-word group project designed to demonstrate understanding of the mate- rial presented in the course and its appli- cation to a specific organization. We asked students to contact an organiza- tion and determine the organization’s leadership training needs. Students also were required to use relevant theory and research evidence to justify the contents of their package. The packages were to include exercises designed to enhance the leadership skills of a particular

group of people according to their train- ing needs. In addition to the evaluation of the training package itself, students were also asked to complete a 5-point- scale peer evaluation of the other mem- bers of their group.

Class participants also completed an individual Leadership Process Reflection paper, which was intended to give them an opportunity to provide a critical reflection of the leadership processes occurring within their team as they creat- ed the LTP. They were asked to identify the good and the poor leadership processes in which they engaged and to determine how consistent these were with best practice in theory. Finally, we required them to demonstrate, in hind- sight, which leadership and management processes might have been better to use and what things they personally would do differently now as a result of the lessons learned in their class activities.

The final course assessment was a 2- hour examination. This exam consisted of 25 multiple-choice questions from

the course text by DuBrin and Daglish

(2003) (15% of final course grade) and

a choice of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 out of 7 short-answerquestions (20%), one of which was on

EI. These questions were designed to test understanding of leadership con- cepts and the student’s ability to apply

them in specific organizational contexts.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Results and Discussion

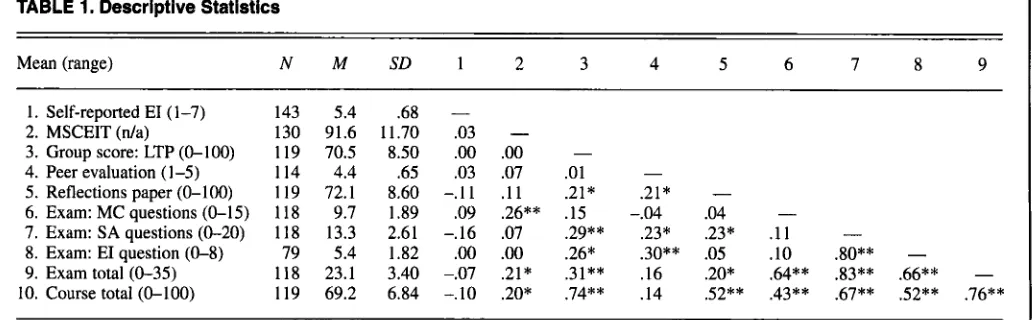

In Table 1, we provide descriptive statistics for the EI measures and assess-

ment scores. Results demonstrate, as

Mayer et al. (2003) warned, that

MSCEIT scores were unrelated to the self-report measure of EI. Scores on the MSCEIT did, however, predict stu- dents’ scores in the multiple-choice sec- tion of the exam, the total exam mark, and course percentages. This result would seem to support Zajonc’s (1998) position that emotional perception skills are related to cognition. Wolff et al. (2002) also posited that emotional intel- ligence is related to clear thinking.

As in earlier research by Jordan,

Ashkanasy, HMel, and Hooper (2002), we found that EI was unrelated to team performance measured at the end of training. Nevertheless, students’ scores on the EI question on the exam (66% chose to answer the short-answer ques- tion on EI; this was the most popular question) were correlated with their scores for the LTP and peer evaluation. Thus, it seems that students’ under- standing of the EI construct (as reflect- ed in their examination question answer) predicted their team and indi- vidual performance in the LTP.

We also determined that there were

no differences in EI scores (in either the

MSCEIT or the self-report measure) between students who chose to com- plete the EI exam question and students who did not choose to complete it. Nevertheless, students who chose the EI question were more likely to have

chosen also to complete the MSCEIT,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

[image:4.612.51.567.539.699.2]xZ

(df = I ; N = 118) = 3.68, p <zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

.05. Apparently, students who demonstratedTABLE 1. Descriptive Statistics

Mean (range) N M

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

SD~ ~ ~~~~~ ~ 1 . Self-reported EI (1-7)

2. MSCEIT ( d a )

3. Group score: LTP (0-100)

4. Peer evaluation (1-5)

5. Reflections paper (0-100)

6. Exam: MC questions (0-15)

7. Exam: SA questions (0-20)

8. Exam: EI question (0-8) 9. Exam total (0-35)

10. Course total (0-100)

143 5.4 .68 130 91.6 11.70 119 70.5 8.50 114 4.4 .65 119 72.1 8.60 118 9.7 1.89 118 13.3 2.61 79 5.4 1.82 118 23.1 3.40 119 69.2 6.84

1

-

.03

.oo

.03

7 1 1

-09 -.16

.oo

-.07

-.I0

2

-

.oo

.07 * 1 1 .26** .07

.oo

.21* .20*

3

-

.01 .21* .15 .29** .26* .31** .74**

-

.21*

-

-.04 .04.23* .23* . l l

-

.30** .05 .10 .80**-

.16 .20* .64** .83** .66** --

.14 .52** .43** .67** .52** .76**

Nore. N ’ s are less than 144 because not all students could be matched to MSCEIT User-ID. * p < .05. **p < .01.

an interest in emotional intelligence by giving up their own time to sit for the MSCEIT also showed preference for the EI exam question.

The question that arose at this point was whether there would be differ- ences between the students who chose to complete the MSCEIT (in their own time) and those who did not, according to their answers to the question about EI on the exam. Indeed, we did find differences: The MSCEIT EI exam

question mean was 5.6

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( N = 6 8 , SD =zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1.6), and the non-MSCEIT mean was

4.0 ( N = 11, SD = 2.4), t(77) = 2.8, p

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

c.01. Interestingly, this difference was also evident in a comparison based on the self-report measure of EI: The MSCEIT EI self-report mean was 5.4

( N = 124,

SD

= 0.6), and the non-MSCEIT mean was 5.0 ( N = 19, SD =

0.8), t(141) = 2.36, p

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

c .05. Theseresults imply that the students who were interested enough to complete the MSCEIT in their own time were more conversant with the EI construct and also had a higher opinion of their own emotional abilities than those who did not complete the MSCEIT.

In summary, the results of this study provide some support for our expecta- tion that emotional intelligence would be related to performance in the course, although this relationship was evident only with respect to the MSCEIT, an ability measure. In addi- tion, we found that performance in the team exercise (LTP) was related to the students’ understanding of emotions as reflected in their answer to the exam question on this topic. Finally, our results showed that the students who took the time to complete the MSCEIT were both more knowledgeable about emotions and scored higher in the self- report measure of EI.

Overall, these results suggest that EI, or at least learning about emotions, can play a role in performance outcomes in leadership teaching. Although the results are preliminary, they do create confi- dence that there is a role for teaching emotions in leadership courses. Further- more, the very fact that the emotional intelligence topic was the most answered question in the exam reflects the overall level of interest that the students in this course expressed in the topic.

Conclusion

The results of this study have impli- cations for the teaching of leadership in business programs. Consistent with Jor- dan, Ashkanasy, Hartel, and Hooper (2002), the study demonstrates that teaching about emotions and emotional intelligence in leadership courses can affect team performance.

Furthermore, our results support Ashkanasy and Daus’s (2002) view that emotions play a potentially important role in the understanding of organiza- tions and extend this view to the teaching of leadership. This approach digresses from the traditional view of leadership training criticized by Ashforth and Humphrey (1995) and based on ideas of rational management. Ashkanasy and Daus and Ashkanasy, Hiirtel, and Zerbe (2002) offered numerous tools to assist managers in managing emotions appro-

priately. Ashkanasy and his colleagues

recommended, among other things, that managers should manage affective events in the workplace, provide training and development to foster emotional dis- play recognition, teach employees how to diagnose emotional displays, and

develop EI in employees and leaders.

The results of the present research rein- force the value of such initiatives and suggest that managers need to act proac- tively to introduce practices that put these tools into action.

Educators of future business leaders must pay more attention to emotional intelligence in their courses. Although researchers still are investigating whether emotional intelligence can be

taught, the results

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of this study suggestthat students in leadership courses should be more than simply bystanders when studying the impact of emotions and emotional intelligence on perfor- mance. Active personal involvement adds an important dimension to educat- ing students about these topics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was funded by an Australian Research Council Large Grant. The authors would like to express their appreciation to Art Shulman, course coordinator, for his cooperation and help- ful advice.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Neal M. Ashkanasy, UQ Business

School, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, 4072, Australia. Electronic mail may be sent to n.ashkanasy @uq.edu.au.

REFERENCES

Argyris, C. (1994). Good communication that blocks learning. Harvard Business Review,

Ashforth, B. E., & Humphrey, R. H. (1995). Emo- tion in the workplace: A reappraisal. Human Relations, 48, 97-125.

Ashkanasy, N. M. (2003). Emotions in organiza- tions: A multilevel perspective. In F. Dansereau

&

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

F. J. Yammarino (Eds.), Research in multi-level issues, vol. 2: Multi-level issues in organi- zarional behavior and strategy (pp. 9-54). Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science.

Ashkanasy, N. M., & Daus, S. D. (2002). Emotion in the workplace: The new challenge for man- agers. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 76-86.

Ashkanasy, N. M., HWel, C. E. J., & Daus, C. S.

(2002). Advances in organizational behavior: Diversity and emotions. Journal of Manage- ment, 28, 307-338.

Ashkanasy, N. M., H w e l , C. E. J., & Zerbe, W. (Eds.). (2000). Emotions in the workplace: Research, theory, and practice. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Ashkanasy, N. M., Hiirtel. C. E. J., & Zerbe, W. J. (2002). What are the management tools that come of this? In N. M. Ashkanasy, W. Zerbe, & C. E. J. Hiirtel (Eds.), Managing emotions in the workplace (pp. 285-296). Armonk, N Y ME Sharpe.

Ashkanasy, N.M., & Tse, B. (2000). Transfor- mational leadership as management of emo- tion: A conceptual review. In N. M.

Ashkanasy, C. E. J. Hartel, & W. J. Zerbe, Emotions in working life: Theory, research and practice (pp. 221-235). Westport, C T Quorum Books.

Ashkanasy, N. M., Zerbe, W., & H w e l , C. E. J. (Eds.). (2002). Managing emotions in the work- place. Armonk, N Y ME Sharpe.

Barsade, S. G., Brief, A. P., & Spataro, S. E. (2003). The affective revolution in organiza- tional behavior: The emergence of a paradigm. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The stare of the science (pp. 3-52). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Becker, T. (2003). Is emotional intelligence a viable concept? Academy of Management Review, 28, 192-195.

Brief, A. P., & Weiss, H. M. (2002). Organization- al behavior: Affect in the workplace. Annual Review Psychology, 53,279-307.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emo- tion, reason. and the human brain. New York: Avon Books.

Dasborough, M. T., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2002). Emotion and attribution of intentionality in leader-member relationships. Leadership Quar- terly, 13,615-634.

Davies, M., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. (1998). Emotional intelligence: In search of an elusive construct. Journal of Personality and Social

DuBrin, A. J., & Daglish, C. (2003). Leadership, an Australasian focus. Brisbane, Australia: Wiley Australia.

Fineman, S . (1993). Emotion in organizations. London: Sage.

Fineman, S. (2000). Emotion in organizations (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

72(4), 77-85.

Psychology, 75,989-1,015.

Fineman, S. (2003).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Understanding emotions at work. London: Sage.Fisher, C. D.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Ashkanasy, N. M. (Eds.). (2000).Special issue on emotions in work life. Journal

of Organizational Behavior, 21(3).

Fox, S . (Ed.). (2002). Special issue on emotions in the workplace. Human Resource Management

Review, 12(2).

Fox, S., & Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2001). The power of emotional appeals in promoting orga- nizational change programs. Academy of Man-

agement Executive, IS(

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

14). 84-95.Friedman, H. S., Riggio, R. E., & Casella, D. F. (1988). Nonverbal skill, personal charisma, and initial attraction. Personalify and Social Psy-

chology Bulletin, 14, 203-21 1.

George,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I. M. (2000). Emotions and leadership:The role of emotional intelligence. Human

Relations, 53, 1,027-1,055.

George, J. M., & Brief, A. P. (1996). Motivational agendas in the workplace: The effects of feel- ings on focus of attention and work motivation.

Research in Organizational Behavior; 18,

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional inteL1igenc.e: Why

it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam

Books.

Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional

intelligence. New York Bantam Books.

Goleman, D. (2000). Leadership that gets results.

Harvard Business Review, 78(2), 78-90.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart:

Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley,

CA: University of California Press.

Humphrey, R. H. (Ed.) (2002). Special issue on emotions and leadership. Leadership Quarterly,

l3(5).

Huy, Q. N. (2002). Emotional balancing of orga- nizational continuity and radical change: The contribution of middle managers. Administra-

tive Sciences Quarterly, 47, 31-69.

Isen, A. M., &Baron, R. A. (1991). Positive affect as a factor in organizational-behavior. Research

in Organizational Behavior; 13, 1-53.

Jordan, P. J., Ashkanasy, & N. M., Hmel, C. E. J. 75-109.

(2003). The case for emotional intelligence in organizational research. Academy of Manage-

ment Review, 28, 195-197.

Jordan, P. J., Ashkanasy, N. M., Hiirtel, C. E. J., &

Hooper, G. S. (2002). Workgroup emotional intelligence: Scale development and relation- ship to team process effectiveness and goal focus. Human Resource Management Review,

Lewis, K. M. (2000). When leaders display emo- tion: How followers respond to negative emo- tional expression of male and female leaders.

Journal of Organisational Behavior; 21,

Lord, R.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

G., Klimoski, R. J., & Kanfer, R. (Eds.)(2002). Emotions in the workplace: Under-

standing the structure and role of emotions in organizational behavior. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Mastenbroeck, W. (2000). Organizational behav- ior as emotion management. In N. M. Ashkanasy, C. E. J. Hmel, & W. .I.Zerbe (Eds.), Emotions in the workplace: Theory,

research, and practice (pp. 19-35). Westport,

C T Quorum Books.

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., Salovey, P., & Sitare- nios, G. (2003). Measuring emotional intelli- gence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion, 3,

Mayer, J., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotion- al intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional

intelligence: Implications for educators (pp.

3-3 1). New York Basic Books.

Mumby, D. K., & Putnam, L. A. (1992). The pol- itics of emotion: A feminist reading of bounded rationality. Academy of Management Review, 17.465486.

Payne, R. L., &Cooper, C. L. (Eds.). (2001). Emo-

tions at work: Theory, research, and applica- tions for management. Chichester, U K Wiley. Pekrun, R., & Frese, M. (1992). Emotion in work

and achievement. International Review of Indus-

trial and Organizational Psychology, 7, 153-196.

Rafaeli, A., & Sutton, R. I. (1989). The expression

12, 195-214.

221-234.

97-105.

of emotion in organizational life. Research in

Organizational Behavior;

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I I , 1-42.Robbins,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

S. P. (2001). Organizational behavior(9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Per-

sonality, 9, 185-21 1.

Simon, H. A. (1976). Administrative behavior: A

study of decision-making processes in admin- istrative organization (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press.

Staw, B. M, Sutton, R. I., & Pelled, L. H. (1994). Employee positive emotion and favorable out- comes at the workplace. Organization Science,

Steiner, E. D. (1972). Group processes and pro-

ductivity. New York Free Press.

Van Maanen, J., & Kunda, G. (1989). “Real feel- ings”: Emotional expression and organizational culture. Research in Organizational Behavior; 11.43-103.

Weiss, H. M. (Ed.). (2001). Special issue-Affect at work Collaborations of basic and organiza- tional research. Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Process, 86( 1).

Weiss, H. M. (Ed.). (2002). Special issue on emo- tional experiences at work. Motivation and

Emotion, 26( I).

Weiss, H., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organisation-

a1 Behavior; 18, 1-79.

Wolff, S. B., Pescosolido, A. T., & Druskat, V. U. (2002). Emotional intelligence as the basis of leadership emergence in self-managing teams.

Leadership Quarterly, 13, 505-522.

Wong, C., &Law, K. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on perfor- mance and attitude: An exploratory study.

Leadership Quarterly, 13, 243-274.

Zajonc, R. B. (1998). Emotions. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology, vol. 1 (4th ed., pp.

591432). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5, 51-71.

22