Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Teaching MBA Statistics Online: A Pedagogically

Sound Process Approach

John R. Grandzol

To cite this article: John R. Grandzol (2004) Teaching MBA Statistics Online: A Pedagogically Sound Process Approach, Journal of Education for Business, 79:4, 237-244, DOI: 10.3200/ JOEB.79.4.237-244

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.79.4.237-244

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 50

View related articles

istance education—from tradition-al correspondence courses con-ducted on an individual basis via regular mail to cohort-based, Web-delivered courses that incorporate synchronous video—is proliferating globally in pri-vate and public sectors (Steiner, 1998). Organizations (academic and otherwise) aggressively market undergraduate- and graduate-level courses and programs, leaving student consumers at risk con-cerning the cost, quality, and usefulness of their education.

Distance education has several defin-ing elements (Steiner, 1995): the separa-tion of instructor and learner during the majority of the instructional process, the use of educational media to unite the teacher and learner and to carry course content, and two-way communication between the instructor and learner. These elements are not, however, defin-ing in terms of operational definition, which makes clear a methodology for delivering quality education at a

dis-tance. Distance education methods can

and do vary substantially.

The lack of empirically validated best practices for distance education con-tributes to hesitation in using this edu-cation delivery medium. Additionally, questions about identifying target audi-ences—how to find the individuals or groups of individuals best suited to

become distance learners—make the whole issue of distance education rather intimidating. Regardless, the “train has left the station,” and not boarding it proactively and knowledgeably seems an inappropriate course of action.

Growth of Distance Education Programs and Courses

The Council for Higher Education Accreditation (2002a) estimated colle-giate enrollment in distance education at 2.2 million students in 2002. Thirty-five of the 50 states in the United States already have statewide virtual universi-ties. Of 5,655 accredited academic

institutions, 35% offered some form of distance learning programs or courses. Of these, 86% held regional accredita-tion. These data attest to the regional accrediting bodies’ leadership in recog-nizing the legitimacy of distance educa-tion as a viable alternative to tradieduca-tion- tradition-al on-campus program and curriculum delivery (Council for Higher Education Accreditation, 2002b).

Smith (2001) listed many of the ben-efits that distance education provides for both students and faculty members. For students, these include accessibility, flexibility, participation, absence of labeling, written communication experi-ence, and experience with technology. Faculty members enjoy the same bene-fits and perhaps employment advan-tages derived from newly gained skills. There are difficulties as well, notably issues concerning interaction and team building, administration of examina-tions, absence of oral presentation opportunities, and technical problems. From the faculty perspective, the time requirement is significant, and activities include designing courses, learning new technologies, and resolving technologi-cal problems. All these factors con-tribute to the strong support for and rapid development of distance educa-tion in many settings, as well as the indifference or hesitation in others.

Teaching MBA Statistics Online:

A Pedagogically Sound

Process Approach

JOHN R. GRANDZOL Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania

Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania

D

ABSTRACT.Delivering MBA statis-tics in the online environment pre-sents significant challenges to educa-tion and students alike because of varying student preparedness levels, complexity of content, difficulty in assessing learnng outcomes, and fac-ulty availability and technological expertise. In this article, the author suggests a process model that devel-ops key learning strategies for the online environment and offers accred-itation- and literature-based guide-lines for overcoming obstacles to sucessful mastery of MBA-level sta-tistics. Intended for faculty members, administrators, and students with lim-ited experience in online education, the model may stimulate discussion and investigation of successful prac-tices appropriate for teaching busi-ness statistics.

CYBER DIMENSIONS

Best Practices

Academic quality, driven by the suc-cessful enabling of learning, requires interaction among faculty members and students. Shea, Motiwalla, and Lewis (2001) reported that top students, although generally satisfied with the distance education environments, de-sired more frequent and faster interac-tion (meaning feedback) with profes-sors. The Council for Higher Education Accreditation (2002b) suggested that programs should “develop a sense of community through study groups” (p. 12). The eight regional accrediting commissions reinforced this view, emphasizing the “community of learn-ing” perspective that suggests that fac-ulty members be involved cooperatively in course creation and delivery and that learning be dynamic and interactive, regardless of the setting (Middle States Commission on Higher Education, 2002). In its study of benchmarks for success in distance education, the Insti-tute for Higher Education Policy (2000) qualified interactivity as the “sine qua nonfor quality” (p. 16).

Larson (2002) argued that whereas traditional education is centered on the professor, distance education is inher-ently student centered. This suggestion has a rather profound implication: Although the instructor may continue to orchestrate the course, the students actually may direct the learning process, relying on their own initiative and frames of reference. Recognizing this perspective suggests questions about how to differentiate these roles. For example, what boundaries should the course establish, and how much flexibil-ity should it allow? This paradigm requires faculty members to mentor, facilitate, and enable while ensuring mastery of fundamental and rigorous statistical concepts and methods (in this case) for which creativity and innova-tion may be problematic.

In the traditional setting, students dis-cuss and exchange ideas about course topics in and out of the classroom. Fac-ulty members are involved in many of these occasions, and they add lecture interaction and office hours. Boose (2001) suggested that professors should first ask themselves how they can

repro-duce the classroom experience or design a course structure that accomplishes learning objectives differently. In an online environment, replicating exchange opportunities requires plan-ning, monitoring, and participating in all such opportunities to ensure knowl-edge is being exchanged and under-stood. Faculty members cannot simply observe, as in a classroom.

The most difficult portion of the tra-ditional environment to re-create is interactive lecture. Although an instruc-tor may rely on written notes to ensure logical flow of presentation and discus-sion, much of the spoken word in a classroom is not scripted, frequently because it is spontaneous. Yet without the unscripted dialogue, learning may be incomplete; hence, special attention must be afforded its proxy. The lecture material links the textbook and related readings and facilitates student partici-pation in all available media. Whatever the number and extent of activities designed to replace classroom lectures, online course professors must ensure their consistency, comprehensiveness, and clarity.

In its comprehensive review of the lit-erature and a survey of faculty mem-bers, students, and administrators at institutions recognized for their exten-sive experience and high-quality dis-tance learning programs, the Institute for Higher Education Policy (2000) identified and then confirmed distance learning program benchmarks in seven categories: institutional support, course development, teaching/learning, course structure, student support, faculty sup-port, and evaluation and assessment. Course developers should use desired learning outcomes to determine the technology to be used, and courses should be designed to engage students in the practice of desired competencies. Effective distance learning requires facilitation of student interaction, in-cluding timely feedback for questions and assignments and instruction in effective research methodologies. Course structure should ensure that stu-dents receive adequate information about the distance learning aspects of the program or course. This should include supplemental information about objectives, concepts, ideas, and

out-comes, as well as expectations concern-ing timely submission of assignments and reasonable timeframes for grading and feedback. Student support should include hands-on training on course-ware, library access, course softcourse-ware, and the like. For the area of evaluation and assessment, findings suggest appli-cation of specific standards measured via several assessment methods.

The School and the Course

Bloomsburg University, located in central Pennsylvania, is one of 14 uni-versities in the state’s system of higher education; it serves a primarily under-graduate population of approximately 7,500 students drawn from neighboring communities and small cities. The MBA program has an enrollment of approxi-mately 100 students who have the option of completing a “generic” MBA or choosing a concentration. Statistical Analysis and Design is a foundation course in the program typically taken by MBA students. Before summer 2002, none of the MBA courses at Bloomsburg were offered via distance education.

Environmental Context

The impetus for developing an online version of this particular course derived from three distinct sources. Studies (Eaton, 2001; IHEP, 2000) suggested that individual faculty members seeking personal development in technological learning enhancements or seeking to satisfy innate desires for new knowl-edge initiate online courses and even development of entire online programs. A second reason for considering online course development at Bloomsburg was a predicament resulting from traditional delivery of the MBA at a location 50 miles from the main campus. Having made the commitment to allow potential students to complete MBA degree requirements within a definite time-frame and without requiring attendance at the main campus, the participating departments’ faculty resources were being stretched to the limit as they struggled to ensure that all courses were taught by instructors with doctoral degrees. Finally, in an effort to increase the growth of the program and decrease

the time required to complete it, pro-gram administrators determined to offer some or all of the foundation courses during summer sessions. Because very few of Bloomsburg’s MBA students are full-time, offering students a way to meet family and work commitments in addition to completing course work seemed reasonable. Making foundations courses more accessible (via distance education) enables new students to enroll in core courses in their first fall semester, thereby speeding the time to degree completion.

Statistical Analysis and Design

My pedagogical approach to the busi-ness curriculum concurs with Markel’s (1999) view that pedagogy is not instructional-mode dependent. My approach, interpreted specifically for an MBA statistics class, can be stated as follows: The class should impart a solid foundation of knowledge and theory and a thorough understanding of statis-tical methodologies through extensive demonstration of applications to for-profit and not-for-for-profit organizations. By integrating research, writing, presen-tation, and computer skills, along with case analyses and technical methodolo-gies in the learning experience, students successfully progress from learning why

certain knowledge is necessary and important, through learning what the knowledge actually includes, to learn-ing how to use and apply it. Ideally, graduates will have a general knowl-edge of business statistics and will know more than what to do and how to do it—they will know why they are doing it.

This pedagogy drives the develop-ment of the course objectives and con-tent, as well as its structure and assess-ment techniques.

Behavioral Objectives

Each course in the College of Busi-ness has behavioral objectives—in other words, what students are expected to do with the knowledge gained in the course. The objectives that follow represent the knowledge, skills, and abilities that stu-dents are expected to achieve in this course regardless of the delivery media:

• Learn and understand the purpose, value, and methods of descriptive statistics

• Learn and understand key concepts of probability theory

• Learn and understand the purpose, value, and methods of inferential statistics

• Transform data into management information using probability and statistics

These objectives become the foundation of assessing learning outcomes and drive the development of the appropri-ate online capabilities.

Content

The content for this course consists of typical topics ranging from descriptive statistics to multiple regression. Al-though the literature suggests that some of these should be replaced by more applied topics, such as quality control or time series, this issue is not a key source of discontent in Bloomsburg’s program because these additional topics are cov-ered elsewhere in the program.

Expectations

A recurring theme in the research lit-erature and accrediting guidelines is the need to make clear to students what is expected, not only in terms of output (homework, papers, etc.) but also in terms of the level of knowledge and ability that they should achieve. Phipps, Wellman, and Merisotis (1998) suggest-ed clearly identifying a set of outcomes in terms of expected student knowledge, skills, and competency levels. Advising students about the program course, its

objectives, concepts, ideas, and out-comes, is a key practice among the most successful practitioners of distance edu-cation (IHEP, 2000).

Transitioning the Course

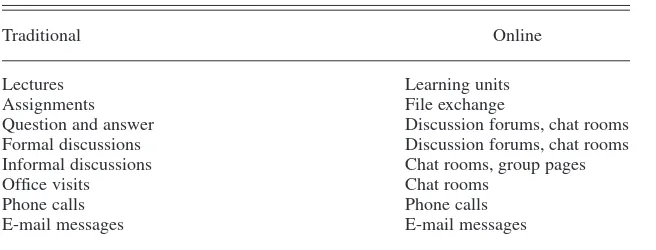

In Table 1, I list the principal opportu-nities for interaction in the traditional learning environment and propose corre-sponding alternatives in the computer-mediated (Internet) learning environ-ment. These opportunities cover formal and informal professor-to-student ex-changes as well as corresponding stu-dent-to-student opportunities. Assuming acceptance of the preceding discussion on the importance of interactivity in the learning process, a key challenge for fac-ulty members teaching in online courses is the transformation of traditional opportunities by effective use of online capabilities. Experience suggests that this is no easy task; a semester of seem-ingly innumerable e-mail messages made this quite evident to me.

Care in transforming the standard tra-ditional business statistics class is essential. Otherwise, existing students could be alienated, with a potential neg-ative impact on planned program growth. Despite the availability of dis-tance learning course software within the state system without any explicit cost to individual member universities, there had been very little activity at this campus in this arena; hence, a gradual phase-in, from the Web-enhanced (blended) course to the Web-based (online) course, was chosen as the appropriate strategy. I used this approach by adding Web enhancements to all of the courses that I taught, both graduate and undergraduate, on and off

TABLE 1. Interactions in Traditional and Online Learning Environments

Traditional Online

Lectures Learning units Assignments File exchange

Question and answer Discussion forums, chat rooms Formal discussions Discussion forums, chat rooms Informal discussions Chat rooms, group pages Office visits Chat rooms

Phone calls Phone calls E-mail messages E-mail messages

campus. Students began to appreciate the learning or improving of skills relat-ed to time management, technology, and electronic communication.

Initially, only distribution of docu-ments—syllabi, course outlines and schedules, assignment guidelines and formats, and any supplemental reading material or information—was handled via the course Web site. Next, I added announcements dealing with course requirements, learning opportunities, assignment submissions, and examina-tions. After these, I added discussion forums for questions about homework and other class activities, and finally, I created examinations for online applica-tions and scheduled them in on-campus computer labs.

Realizing that student feedback was essential to additional support for further distance learning activities, I developed a multiquestion supplement to the approved student evaluation adminis-tered each semester. My questions addressed students’ use and opinions of the online courseware and course-related software. Results showed significant interest in and appreciation of the Web-based enhancements. Having support-ing data before I initiated the online courses proved a significant benefit, because the contractual environment at Bloomsburg commands supplemental payments for online course develop-ment and teaching. Budgets are usually

an issue, and fortunately, opinions were not the deciding factors.

Online Version

The online version of Statistical Analysis and Design at Bloomsburg University does not have a unique course description. An advertisement describing the mechanics of the course, the time frame in which it would occur, and the faculty member overseeing its development and delivery was made available to all current graduate students and all new program applicants.

Upon registration, students received information about how the course would be conducted; they were also advised of required attendance at two on-campus sessions. During the first session, held in a computer lab at the beginning of the course, students were walked through the course software (in this case, Black-board). They enrolled themselves in the course Web site and practiced with all of the courseware features that would be used: announcements, discussion forums, file exchanges, virtual classrooms, and other student tools. These initial sessions ensured that all students had at least a basic level of familiarity with and compe-tency in courseware functions. The sec-ond session consisted of an in-lab soft-ware demonstration that was scheduled to coincide with the teaching of relevant course content.

The course Web site was organized through Blackboard’s existing frame-work. In Table 2, I depict this structure. Note the detail provided in the course information section, the variety of interaction opportunities listed under “Communication,” and the information provided concerning assignments, all of which were intended to facilitate the community of learning mentioned previously.

To maintain timely, sequential, and cumulative learning of the course’s con-tent, I made material available on the various Web pages 1 week before it was listed in the course schedule. This pre-vented students from getting too far ahead of their peers or simply attempt-ing to complete all of the graded work in a very short time period, forfeiting the benefit of student and faculty inter-actions. For this same reason, all assign-ments had due dates that could not be exceeded without penalty. Students did have the option to submit their work earlier if personal or work conflicts pre-cluded them from submitting on the actual due dates. Initial submissions for discussion forums had mandatory post-ing dates, which helped alleviate the common difficulty of later postings’ sounding too much like earlier ones. Additionally, all students were required to attend at least 1 hour of online chat (virtual classroom) per week, during which they were to present problem

TABLE 2. Course Web Site Structure

Course information Faculty information Assignments Course documents Books

Syllabus Introduction Homework Introduction Business Statistics

Calendar assignments Learning objectives in Practice

File names Homework Tasks Other readings of Word file format exercises Descriptive statistics interest Excel file format Best of class Learning objectives

Online chats Research paper Visual statistics Practice quizzes Tasks

Midterm examination Probability

Final examination Discrete random variables Faculty and course Continuous random variables

evaluation Sampling distributions Confidence intervals Hypothesis testing

Two-sample statistical inference Experimental design and

analysis of variance

Simple linear regression analysis Multiple regression analysis

solutions, answer the instructor’s ques-tions, contribute to discussions, and ask any unresolved questions.

The issues of originality, interactivi-ty, and applicability are important in all courses. In the online environment, these become even more important, as students do not have the opportunity for simultaneous discussion and obser-vation. For example, in a traditional classroom, the instructor can draw a graph and respond to comments or questions as the picture unfolds. Although this is possible during a vir-tual classroom, time constraints usual-ly limit these opportunities. For this reason, along with a pedagogy that encourages providing both analytical and visual explanations of key con-cepts, techniques, and methodologies, choosing a textbook that included an Excel add-in (with tutorials in chapter appendixes) and supplementary soft-ware that provided graphic depictions of all covered statistical concepts proved critical. Another useful tech-nique was the weekly requirement that students either discuss, in jargon-free language, a particular concept or ana-lytical result or actually conduct an experiment using a statistical technique (e.g., ANOVA or regression) and pre-pare a report for the discussion forum for all other students to see and dis-cuss. The following is an example of this requirement:

After thoroughly reviewing Section 7.3, Sample Size Determination, create a busi-ness scenario that requires determination of a sample size for estimating a particu-lar population mean. Refer to the formula on page 257 of the text, and read the para-graph directly under it. Choose a reason-able value for B (error bound), and follow the second alternative for estimating the population standard deviation described on page 259. Then compute sample sizes for both a 95% and a 99% level of confi-dence. To respond successfully, you must provide a clear and concise narrative describing this particular business sce-nario, including the characteristic of interest, the unit of measurement, justifi-cation for the error bound value chosen, calculation of the standard deviation esti-mate, the sample size results, and one-sentence “translations” for each.

Note that this example is perfectly suit-able and appropriate, yet optional, for a traditional MBA statistics class. In the online environment, the option becomes a necessity.

In addition to the weekly discussion forums, students participated in a variety of assignments that gave them opportu-nities to learn via their own information filtering system—visual, auditory, or kinesthetic (Torres, 1985). They solved homework problems, responded to inquiries from the instructor in online chat rooms, prepared case analyses and received both individual and summary feedback, researched and prepared a report on the misuse of statistics in the media, completed instructor-prepared

tutorials in course-related software, reviewed outstanding work from other students, initiated group discussions or online chats, and read textbooks, sup-plemental articles, instructor notes, PowerPoint presentations, and other Web sites. Each content lesson con-tained a list of tasks detailing pertinent student activities.

Assessing Learning Outcomes

Use of multiple assessment tech-niques is necessary to derive reliable results specific to individual students. My pedagogy incorporates this perspec-tive regardless of environment. The intent is to enable students to succeed and to provide ample opportunity for them to demonstrate their understand-ing of and ability to apply the course content. Measuring how well students achieve the behavioral objectives of an MBA statistics course requires frequent and varied assessments of direct appli-cations of statistical methodology and techniques to practical business prob-lems, issues, and opportunities.

Compared with the traditional ver-sion of the course, the online verver-sion has nearly identical assessments; how-ever, their frequency and intensity are greater. For example, although both delivery formats require that an Excel spreadsheet solution to a homework exercise contain adequate explanations for all methods and results, the two for-mats handle discussions in very differ-ent ways. In the traditional classroom, instructors observe and listen to stu-dents’ comments and perceptions. In the online environment, comments must be written, which usually requires more effort from both the students and instructor. An advantage of the virtual classroom feature is the automatic archiving of all communications. Facul-ty members and students can access transcripts of past chats to determine levels of participation and accuracy or to review guidance and explanations. This is similar to automatic note taking and attendance recording.

A comparison of examination results from online and traditional sections of this course (run in nonconsecutive semesters) shows conflicting results from this assessment measure. Applying

Web resources Communication Student tools Research Web resources Send e-mail Digital drop box Problem solving and Discussion board Edit your homepage

statistics Web resources Virtual classroom Personal information Roster Calendar

Group pages Check grade Manual Tasks

Electronic Blackboard Address book

the small sample t test for the means suggests no significant difference (H0: µ1 – µ2 = 0) between these two groups of students in scores from identi-cal midterm examinations (p value = .26), whereas the same hypothesis can be rejected (pvalue = .02) for the final examination. Like so many other empir-ical reports (Russell, 2002), these results are inconclusive because of their con-flicting implications. Also, relying sole-ly on test scores is a recognized weak-ness of learning outcomes assessment.

Student Satisfaction

Several studies (Council for Higher Education, 2002a; IHEP, 2000; Phipps & Merisotis, 1999) suggested the importance of measuring overall student satisfaction with the distance learning experience in addition to assessing learning outcomes. Students in both the traditional and online course offerings completed identical versions of Bloomsburg’s standard faculty and course evaluation. All students also completed a supplemental survey addressing the Web-based and software features available within the course structures.

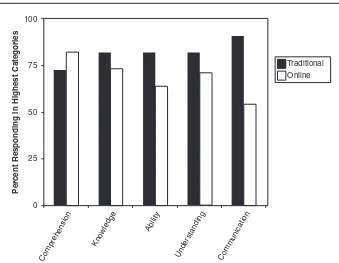

In Figure 1, I show comparative results for these identical surveys from the same two course sections used for the comparisons of test scores. These results for the questions pertaining to instructor-based traits are virtually iden-tical. Small enrollments precluded z

tests of these respective proportions. In Figure 2, I show results typically associated with the learning that occurs, including questions about students’ self-perceptions of knowledge, ability, understanding, comprehension, and communication. With the exception of communication skills, results were again similar, with differences due to responses from one or two students (of the 11 or 12 in these sections). Note also that the results do not include students “in the middle,” but only those respond-ing in the two most positive response categories (on a five-point scale).

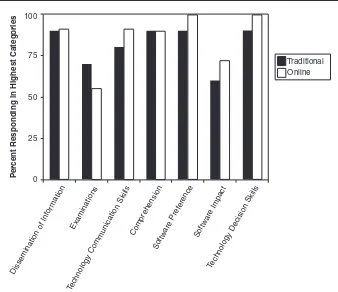

Finally, the data in Figure 3 suggest several interesting and beneficial advan-tages based on students’ perceptions about various course tools, corollary competencies, and personal learning

strategies. The response scale for these items did not include a middle ground (the scale included strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree,

andstrongly disagree). In fact, the only

item on which online students expressed lesser preferences than traditional

stu-dents pertained to Blackboard-delivered course examinations. This lower satis-faction correlates with the inconclusive (weak) results of statistical tests dis-cussed previously. Otherwise, they rated the online experience higher than its tra-ditional counterparts on improvement of

P

e

rcent Responding in Highest Categories

100

75

50

25

0

Enthusiasm Prepared Grading

Ev

aluation Clar ity

Significance Independence

Encour agement

FIGURE 1. Student evaluations: Comparison of traditional versus online instructor-based traits.

Traditional Online

P

e

rcent Responding in Highest Categories

100

75

50

25

0

Comprehension Kno

wledge Ability

Understanding Comm unication

FIGURE 2. Student evaluations: Comparison of traditional versus online learning perceptions.

Traditional Online

their technology-based communication and decision-making skills and on the value of the accompanying application software. Results were nearly identical for items pertaining to the value of the Web site for disseminating information and its contribution to learning course content. Note that the traditional course from which these data derive did incor-porate the Blackboard platform and use of basic Web capabilities in addition to the weekly class meetings.

Conclusion

The benchmarks established in the IHEP (2000) study were applied in the successful transition of this course to the distance format. Desired outcomes, stated as behavioral objectives in the course syllabus, directed the course structure to levels of technological com-petence that all students could be expected to have. The activities for stu-dents, the software tutorials, required research, self-designed experiments, discussion forums, homework exercis-es, and examinations, motivated (in fact, required) students to become engaged

fully in the application of statistical methods to business contexts. Students knew expectations in terms of the vol-ume and level of work, as well as the time constraints and submission requirements. The instructor remained cognizant of and responsive to timely (i.e., rapid) and constructive feedback. Students received early and repeated information about the course, how it worked, and the different activities that they would experience. Results were assessed through a variety of tech-niques, which allowed every student to demonstrate his or her grasp of the material in the way that enabled each student best.

This case review suggests that peda-gogy is not necessarily a function of delivery environment. This transition of an MBA statistics course to an online format was driven by professional de-velopment, cost, and student conve-nience factors, without a strategic initia-tive to create an online program of study, and the results of this study show that pedagogy was not compromised. Creat-ing the course structure based on accred-itation standards and ideals at the

gener-al (regiongener-al) and specific (AACSB) lev-els, which include the need for interac-tivity among students and faculty mem-bers, is an appropriate strategy. My original intent—to create at least as many opportunities for the exchange of information (see Table 1) in the online environment as there are in the tradition-al classroom—appears viable in terms of enabling student learning. Additionally, the improvement in corollary skills (e.g., communication and technology) may be substantial and suggests a valuable advantage for successful online students. Quantitative methods for assessment of differences in learning outcomes were limited in this application. Test scores are only one of the many assessment techniques typically employed, and stu-dent evaluations vary from institution to institution. Qualitative techniques for assessing differences may provide addi-tional insights to true learning outcomes and supplement the numerous “no sig-nificant difference” findings already published in the literature.

REFERENCES

Boose, M. A. (2001). Web-based instruction: Suc-cessful preparation for course transformation.

Journal of Applied Business Research, 17(4), 69–79.

Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA). (2002a). Distance learning in higher education. CHEA update (2). An ongoing study on distance learning in higher education pre-pared for CHEA by the Institute for Higher Edu-cation Policy(June 1999). Retrieved November 13, 2002, from http://www.chea.org/ Research/ distance-learning/distance-learning-2.cfm Council for Higher Education Accreditation.

(2002b).Accreditation and assuring quality in distance learning. Council for Higher Educa-tion AccreditaEduca-tion Monograph Series 2002,1.

Eaton, J. S. (2001). Distance learning: Academic and political challenges for higher education accreditation. Council for Higher Education Accreditation Monograph Series 2001,1. Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP).

(2000). Quality on the line. Benchmarks for success in Internet-based distance education. Washington, DC: Author.

Larson, P. D. (2002). Interactivity in an electroni-cally delivered marketing course. Journal of Education for Business, 77(5), 265–269. Markel, M. (1999). Distance education and the

myth of the new pedagogy. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 13(2), 208–223. Middle States Commission on Higher Education. (2002). Distance learning programs. Interre-gional guidelines for electronically offered degree and certificate programs. Philadelphia: Author.

Phipps, R., & Merisotis, J. (1999). What’s the dif-ference? A review of contemporary research on

P

e

rcent Responding in Highest Categories

100

75

50

25

0

Dissemination of Inf ormation

Examinations

Comprehension Softw are Impact

Technology Decision Skills

FIGURE 3. Student evaluations: Comparison of traditional versus online course tools and corollary skills.

Traditional

the effectiveness of distance education in high-er education. Washington, DC: Institute for Higher Education Policy.

Phipps, R. A., Wellman, J. V., & Merisotis, J. P. (1998). Assuring quality in distance learning: A preliminary review.Washington, DC: Council for Higher Accreditation.

Russell, T. J. The “no significant difference phe-nomenon” Website. Retrieved November 29, 2002, from http://teleeducation.nb.ca/nosignifi-cantdifference

Shea, T., Motiwalla, L., & Lewis, D. (2001). Internet-based distance education—The administrator’s perspective. Journal of Educa-tion for Business, 77(2), 112–117.

Smith, L. J. (2001). Content and delivery: A com-parison and contrast of electronic and tradition-al MBA marketing planning courses. Journal of Marketing Education, 23(1), 35–43.

Steiner, V. (1995). What is distance education?

Retrieved March 25, 2002, from http://www. dlrn.org/library/dl/whatis.html

Steiner, V. (1998). Developing a successful online course: Strategic planning. DLRN-J: The Elec-tronic Journal, 2(2). Retrieved March 25, 2002, from http://www.dlrn.org/library/archives/ dlrnj2_2.html

Torres, C. (1985). The language system diagnostic instrument. In J. W. Pfeiffer & L. D. Goodstein (Eds.). The 1986 Annual: Developing human resources(pp. 99–103). San Diego: University Associates.