In 1994 the ACT Government decriminalized public intoxication with the introduction of the Intoxicated Persons (Care and Protection) Act. However, the original intention of the legislation does not seem to be fully realized in the application of the Act by the police. Accordingly, I believe that consideration should be given to revising the Act to clarify the intended purpose and scope of the legislation.

The AFP should review its approach to the transport of intoxicated people to ensure their safety and that the AFP's transport methods comply with the intent of the law. The AFP should continue to provide training to its officers to ensure that their use of powers under the Act is consistent with the intent of the Act. Review of the Act is supported by the AFP taking into account the matters raised in this report.

As provided for in the legislation, the ACT Government should ensure the provision of Sobriety Shelter. The ACT Government, in consultation with the AFP, may wish to consider the practical benefits of locating such a sobering station in the City Watchhouse.

INTRODUCTION

The investigation also received information suggesting that other police officers may have used their powers under the Act in a manner inconsistent with its original intent. We are also aware of a small number of cases before the ACT Magistrates Court where people have been dealt with on charges (usually resisting arrest and assaulting police) arising from the circumstances of the person being taken into custody by the police. In some of these cases, the magistrates have been critical of the police's assessment of the level of intoxication of the arrested person and in some cases they have found that the actions of the police for taking the person into custody were outside the provisions of the law. .

A further factor impeding the operation of the Act was the closure of the only sobering shelter in the ACT on 22 July 1996. As envisaged by the Act, the shelter provided the police with an alternative facility to to house persons detained in terms of the legislation. With the closure of the sobering shelter, one of the primary objectives of the Act could not be fulfilled.

Consequently, the police can only detain drunk persons in the Stadswachthuis, without the possibility of release to a sober shelter.

OPERATION OF THE ACT

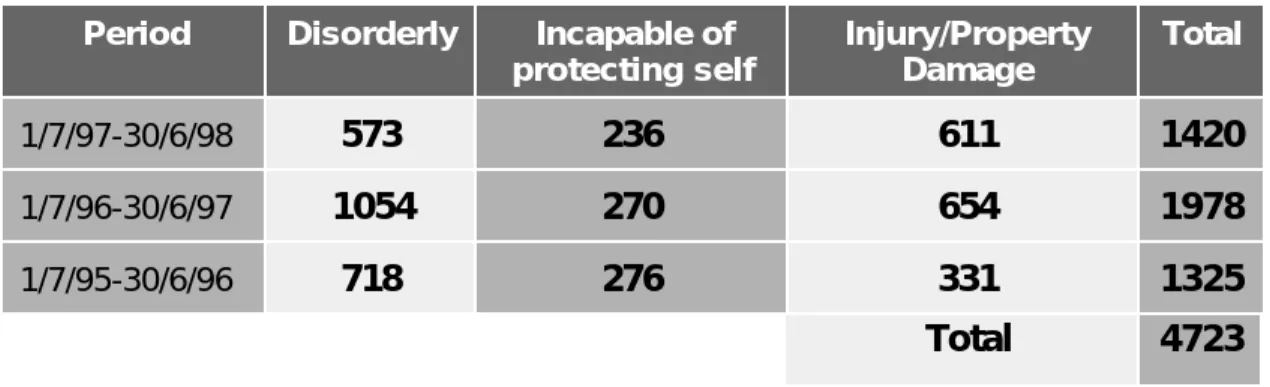

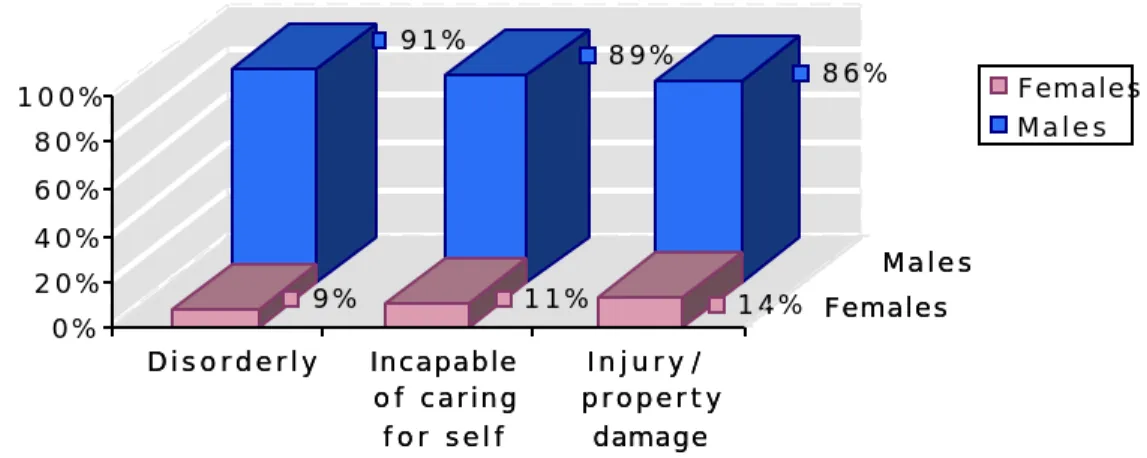

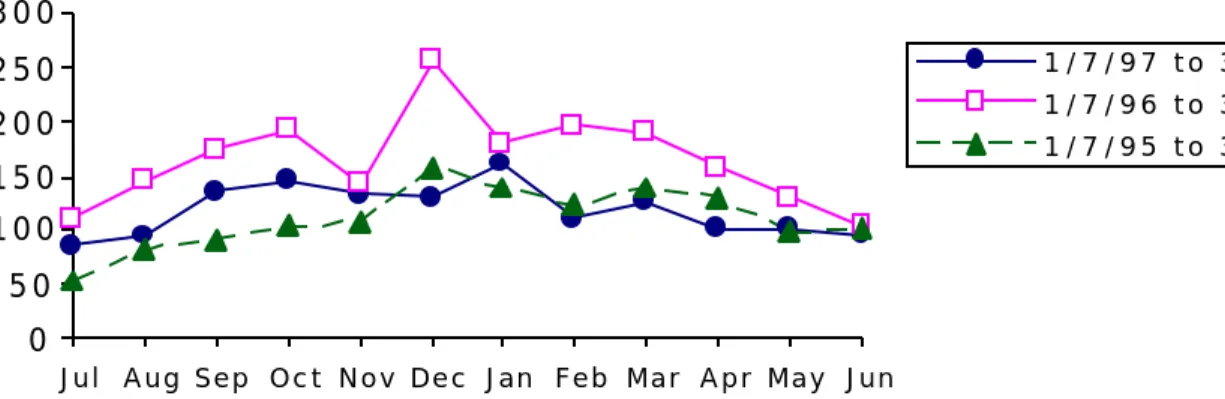

The nearly 50% increase in detentions in 1996-97 suggests either a significant change in community behavior or. Although the cause of this reduction has not been investigated, it is noted that the reduction followed the start of the study. Figure 3 gives an overall picture of the share of persons placed in pre-trial detention over three years based on the various criteria of the law.

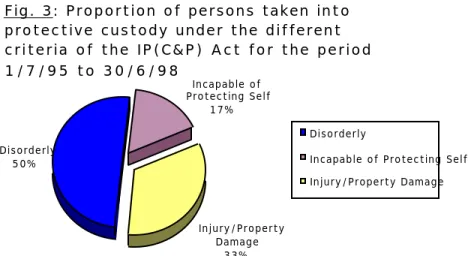

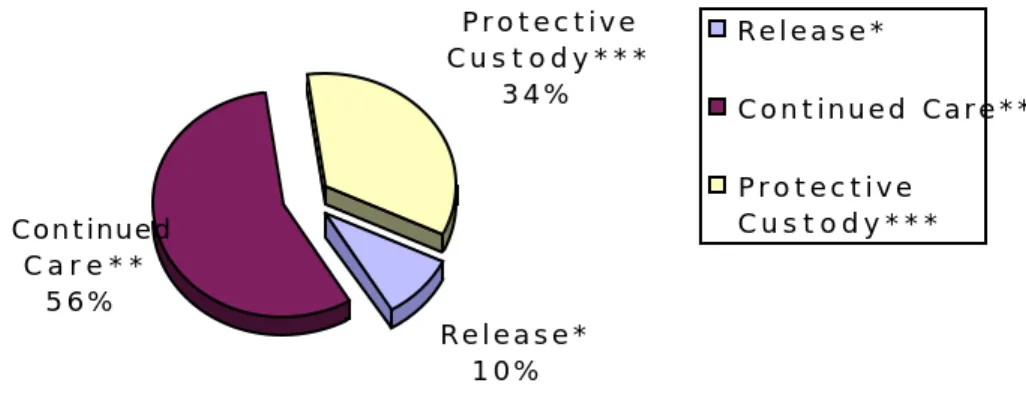

The majority of individuals released into the care of the previous sobering shelter appear to be from the remaining 17%, described as unable to protect themselves. In Figure 4, the data is also examined for gender differences in detentions under the different criteria of the law. To get a hands-on picture of the police's application of the law, the Ombudsman's investigators held a series of discussion meetings with the police of the various ACT regions.

In addition, the Ombudsman's investigators accompanied police on two occasions to the City Beat in Civic and Manuka to see first-hand the application of the law. The Ombudsman's investigators took note of certain comments from officials pointing to possible abuses of the provisions of the law. Helpful discussions were also held with senior ACT Region Police and the Secretary of the Australian Federal Police Association's ACT Section.

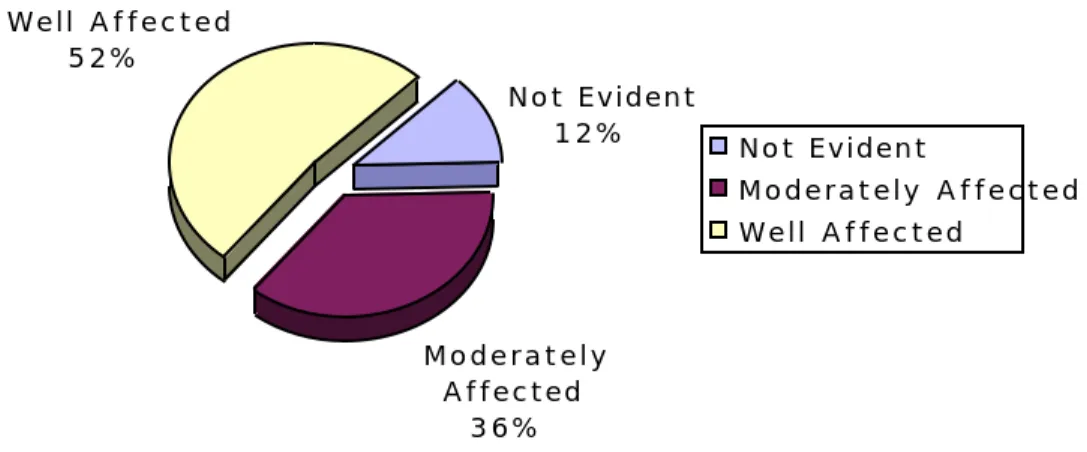

On his arrival at the police station, the custody sergeant examined the young man in the back of the police vehicle and determined that the young man was too intoxicated to be kept at the police station. As part of the qualitative information obtained about the police's use of the law, a sample of videotapes of 146 detained persons processed through the "on-line collection" procedures at the City Watch House during the period 1/1/97 to 30 /6/97 was reviewed by the Ombudsman's investigators. However, the Ombudsman considers that the video evidence provided good general guidance on the most important signs of intoxication and the condition of the arrested.

Worryingly, 12% of those arrested who were seen did not appear to show signs of intoxication. Approx. 400 people could fit into this category if the number was reflected consistently over the period of operation of the law (see also case study 4 below). In some cases, the police do not complete an adequate assessment of the condition of people they suspect of being intoxicated and in need of protective custody.

Equally important, the police must be careful to reflect the care and protection objective of the Act through their actions and communications. When the young woman was informed by the detention sergeant of the basis of her detention, she denied that she had consumed alcohol.

LEGISLATION AND GUIDELINES

The power of detention is supplemented by a provision for the police to release intoxicated persons into the care of the manager of a licensed place under Section 4(5) of the Act. The law also allows an intoxicated person to be released by the police at any time into the care of a responsible person (as defined by law). There are two other aspects of the law that warrant further discussion, as the Ombudsman believes that they have had a significant impact on its operation.

This creates a potential overlap between the Act's protective custody provisions and summary offense provisions. Since the use of police powers under the Act is generally not subject to judicial review, it may become a convenient tool for maintaining public order rather than, as intended by the Act, providing for the care and protection of intoxicated persons . The sale of alcohol and the licensing of premises in the ACT is regulated under the Liquor Act 1975.

Police officers and inspectors working under the registrar have powers under the Act for the purpose of investigating certain offences. However, the guideline does not talk about the application of the law in relation to street offenses or the management of anti-social behaviour. This increases the risk that the law may be inappropriately used by the police as a means of control rather than caring for and protecting drunk people.

The ACT Intoxicated Persons (Care and Protection) Act does not require police officers to charge offenders where an offense has been committed. Instead, the Act contains criteria such as 'disorderly behaviour' and 'damage to property', creating an overlap with the street crime provisions of the ACT Crimes Act 1900. This overlap means that the Act allows police officers to use protective custody instead of or in in connection with provisions on street crimes.

I am of the opinion that these police practices create a risk that the community will view the operational effect of the Act as 're-criminalising'. The interface between summary infringement provisions and protective custody in terms of the Act is clearly demonstrated in the following case study. Two additional levels of review may be included in the Act and/or through AFP operational guidelines.

I think that the use of defensive protection by police in relation to intoxicated persons should be subject to greater external scrutiny than currently exists under the law. Further, the amended definition should be the accepted standard for AFP officers exercising their powers under the Act.

SOBERING UP SHELTER

The closure of the ADDINC sobering shelter in July 1996 meant that the police did not have the option of accommodating intoxicated persons in a shelter. From the information gathered for this report, to effectively meet the intent of the legislation and the needs of the community, a sobering shelter in the ACT with a capacity for 20 beds (15 male and 5 female) appears necessary to be. If the purpose of the shelter is to provide a place where persons can voluntarily seek care and protection, it should be where there is the greatest need.

An option for a clear shelter might be to modify part of the City Watch House. Co-locating the Sobering Up Shelter within the City Watch would also provide an integrated approach to the management of intoxicated persons along with space for early healthcare intervention and education programmes. It is likely that this option will reduce the associated costs of establishing a separate clarification facility and its ongoing operational costs.

I believe that a sobering up facility should be re-introduced into the ACT to ensure that the police have the option of releasing intoxicated persons into the care of a shelter, as envisaged by the Act. The ACT Department of Health and Community Care has advised that the establishment of a Sober shelter endorses the government's policy. The department conducted a tender process for an operator of the shelter, but no contract was awarded.

Pending a resolution to establish a permanent sobering facility, the AFP is supporting further research in consultation with relevant ACT government agencies and the ombudsman service into the identification of alternative options for the early transfer of intoxicated individuals to the care of a responsible adult, or alternative arrangements. I intend for my office to review the operation of the revised intoxication management regulations and procedures within 12 months. While it is about sobering up shelters, it is important that the AFP is aware of the principles underlying the standard.

Although the Commission's report mentions the Act only in passing, it makes several recommendations in relation to 'preventive justice', an aspect of police work strongly emphasized by the police in their discussions with the Ombudsman's investigators. For example, he recommended the possible creation of a formal power to separate people to be used strictly as an aid to prevent a possible breach of the peace. ACT Department of Health and Community Care, Re-establishing a sober haven in the ACT: A discussion paper, June 1997.