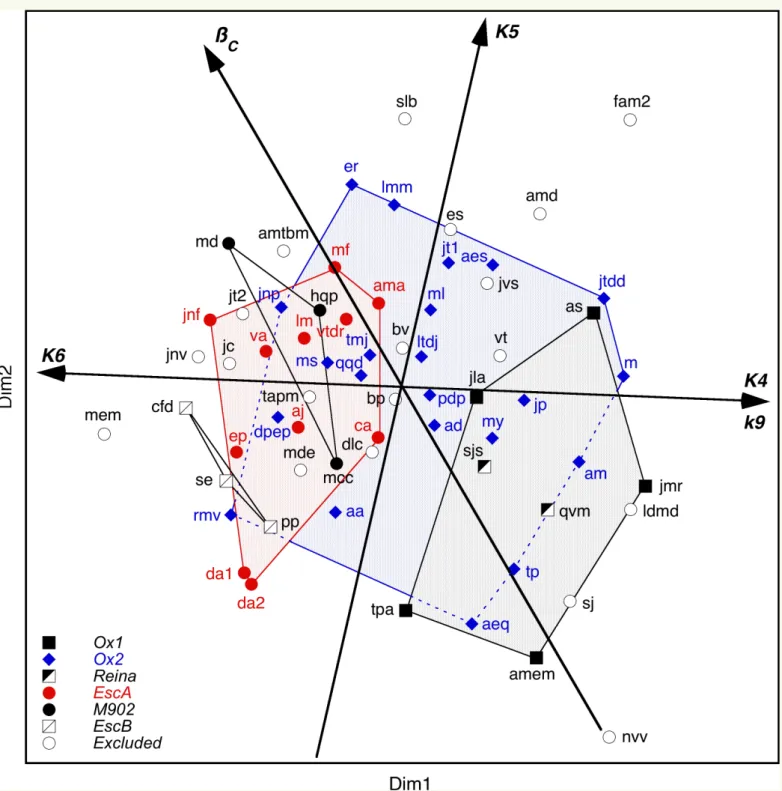

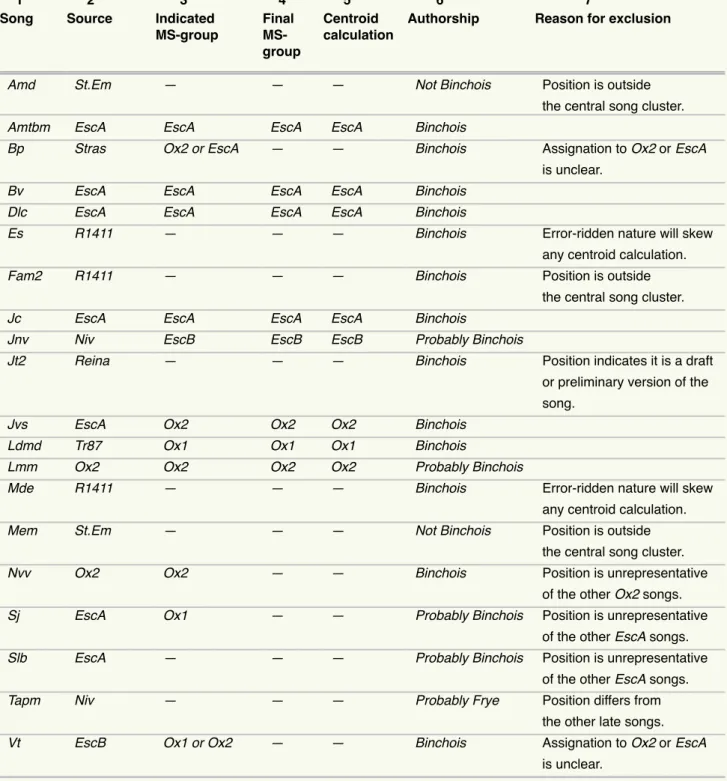

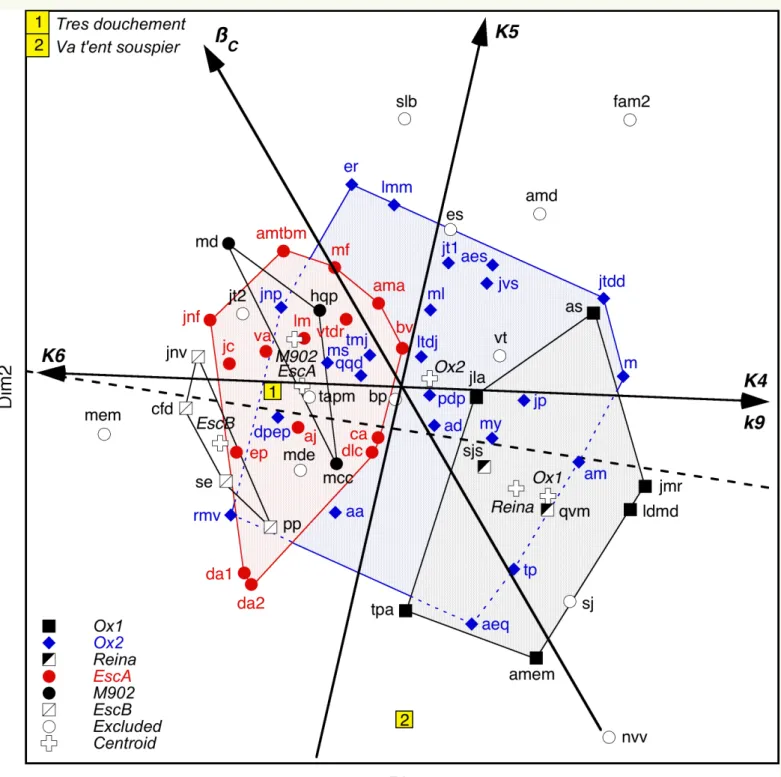

In the melodic analysis, the degree of conjunctivity (the predominance of stepwise movement) of the superius, countertenor and tenor voices was assessed by calculating the slope (ß) of the power spectrum of the MIDI pitch sequence of each voice. Although this provides no evidence to contradict the attribution to Binchois in Ox, this song must be excluded from M-Ox2 and its centroid calculation since its position in the configuration, which is not representative of the other M-Ox2 songs, the result of the centroid calculation.

Song Chronology

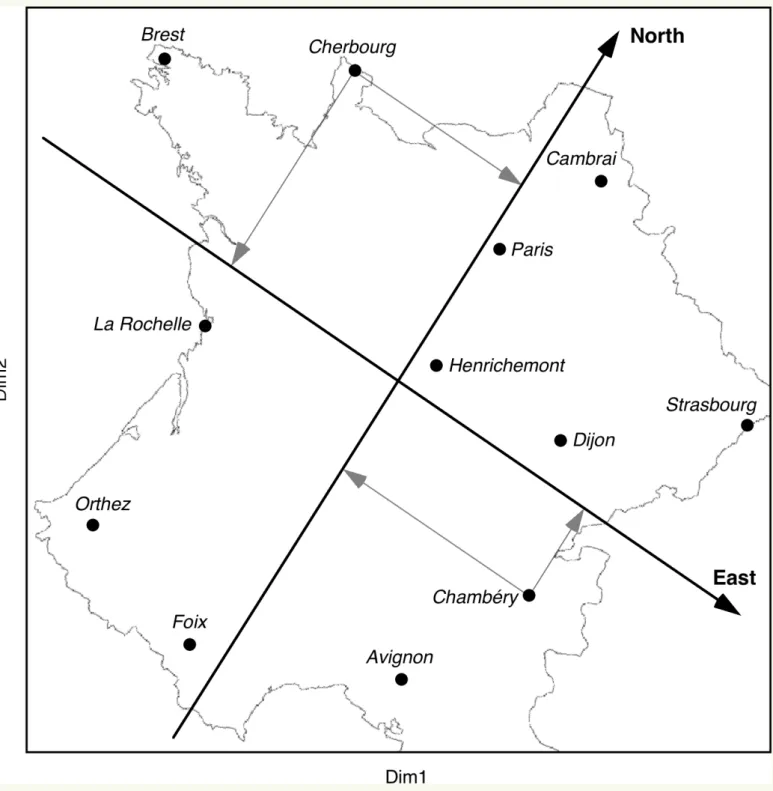

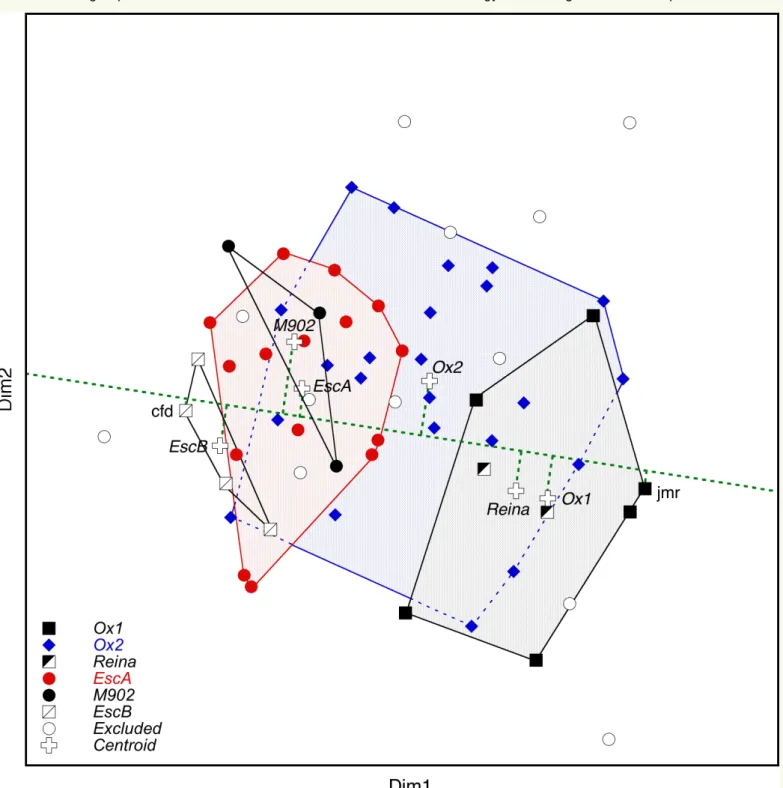

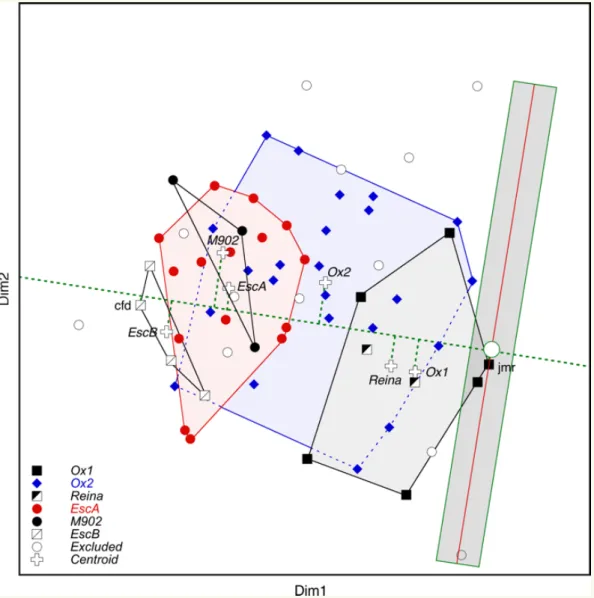

Stylistic Change and the MDS Configuration

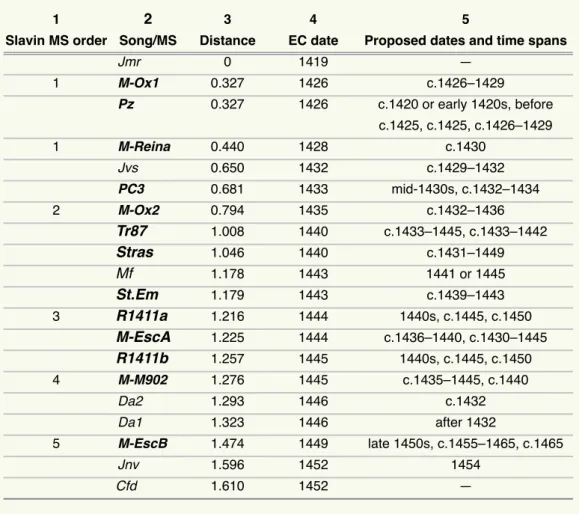

Conversion of Distances to Stylistic Dates

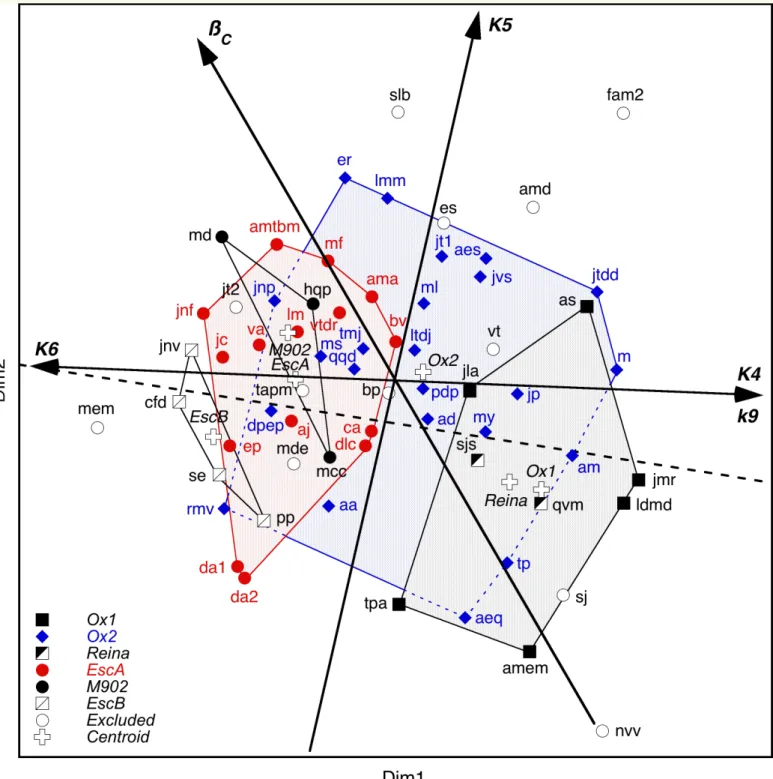

2, regarding the final assignments of the excluded songs to the chronological manuscript groups M-Ox1, M-Reina, M-Ox2, M-EscA, M-M902 and M-EscB and their inclusion in the centroid calculations. When mapped onto this span, the distances between the songs and the centroids along the centroid trajectory resulted in the stylistic dates given in column 4 of Table 4.

Conversion of Stylistic Dates into Equivalent Chronological Dates

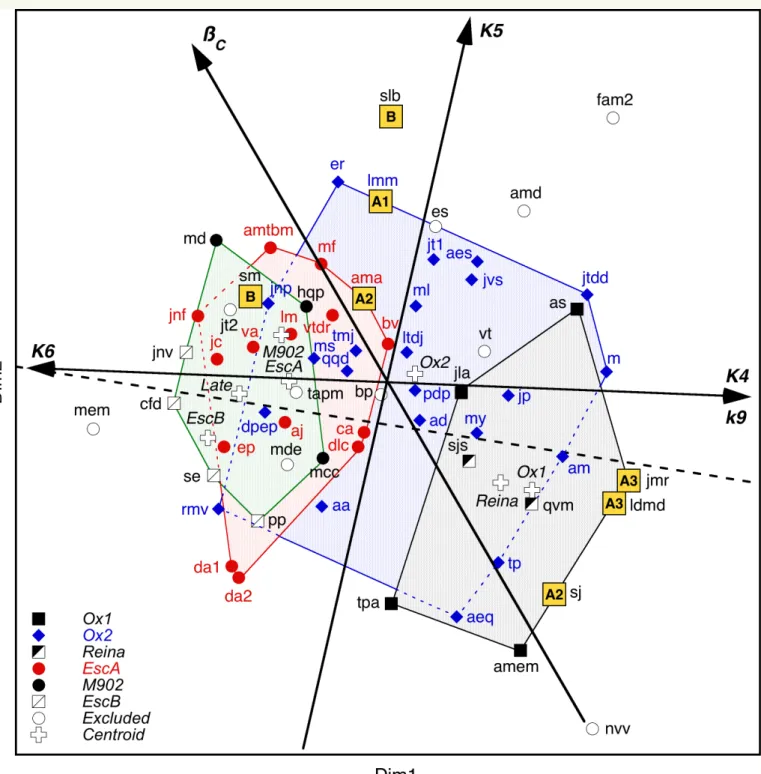

Here the white circle in the dark band represents Binchois, the dark band represents the limited range of values for the dyadic and melodic variables at any given stage of Binchois's output and each step of the band along the centroid progression is at approximately two year intervals. The chronological order of Binchois' songs and the manuscript, manuscript-group and style-period centroids (in bold) derived from their perpendicular positions relative to the centroid progression obtained from the linear best fit to the M-Ox1, M-Ox2, M - EscA and M-EscB centroids, along with their distances along the progression, stylistic and equivalent chronological (EC) dates and style period. Songs excluded from the manuscript groups have EC dates in parentheses in column 5 and songs with stylistic dates more than two years after the EC date of their associated manuscript group centroids have EC dates indicated by the.

The centroid progression distances and EC dates for selected subjects from Table 4 compared with the dates and time periods suggested for them in the literature.

Composition Dates

However, when the characteristics of the Binchois songs in Tr87 are examined in more detail, as described in the section entitled Songs in Tr87 below, not only is the disparity between the EC and the proposed dates explained, but also the EC date of 1440 for Centroid i revised Tr87 agrees with the findings of Wright and Saunders despite being determined on the basis of only two songs (B-Ama and B-Lmm). Here, the EC date of 1443 for this song, while falling in the middle of the time span of the above death dates, does not allow us to decide between any of the possible candidates. These EC dates are easily explained, however, by assuming that Binchois' compositional activity ceased around 1452, which would result in the M-EscB and EscB chants being earlier chants found only in a later source, and the disparity subsequent between EC. and proposed dates.

First, with three exceptions (M-EscB, which is easy to explain, Tr87, which is listed in the section titled Songs in Tr87 below, and B-Da), the EK dates for all manuscript groups and the individual numbers within the time spans cover or are close to the dates proposed for them in the musicological literature.

A Revised Style Chronology for Binchois’s Songs

Here both versions of B-Da are adjacent in configuration because the only difference between them is their countertenors and consequently their ßC values (degree of countertenor conjunct). However, their association and their EC dates of 1446, suggesting that both versions are contemporaneous, support Slavin's view that this song was composed some time after the compilation of Ox (i.e. after c. 1436) and his conclusion that 'there is no firm justification for claiming compositional priority for either version [of B-Da]' (Slavin 1988: 61n36; 1992a: 39). Taken together, this not only confirms that the line of best fit to the centroids of the manuscript group (the centroid run) serves as a chronological yardstick, going from the earliest to the latest songs in a composer's oeuvre, but also indicates that the distances along the line closely correspond to both the relative lateness of the style and the actual elapsed time, with the results in Tables 4 and 5 indicating that the EC dates are likely to be accurate within plus or minus two years, a factor that would also explain the difference between the EC and proposed dates 1452 and 1454 for B-Jnv.

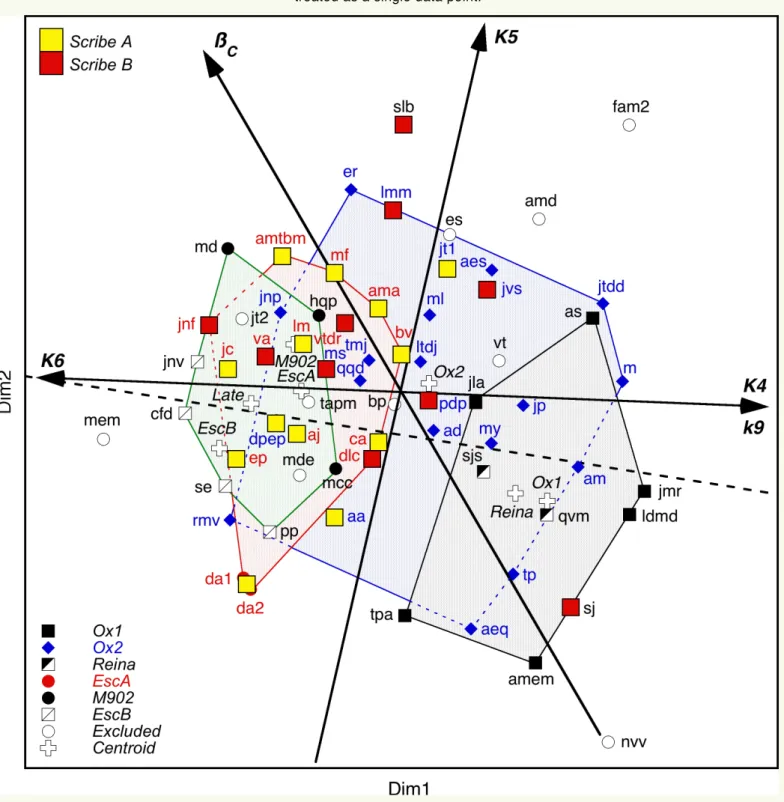

Finally, since the centroid progression is in the same direction as the K6-K4/k9 vector, this supports the above hypothesis that the K6-K4/k9 vector reflects a chronological trend in Binchois' superius-tenor duets, where his use of fourths and ninths decreased over the course of his career , and his use of sixths increased.

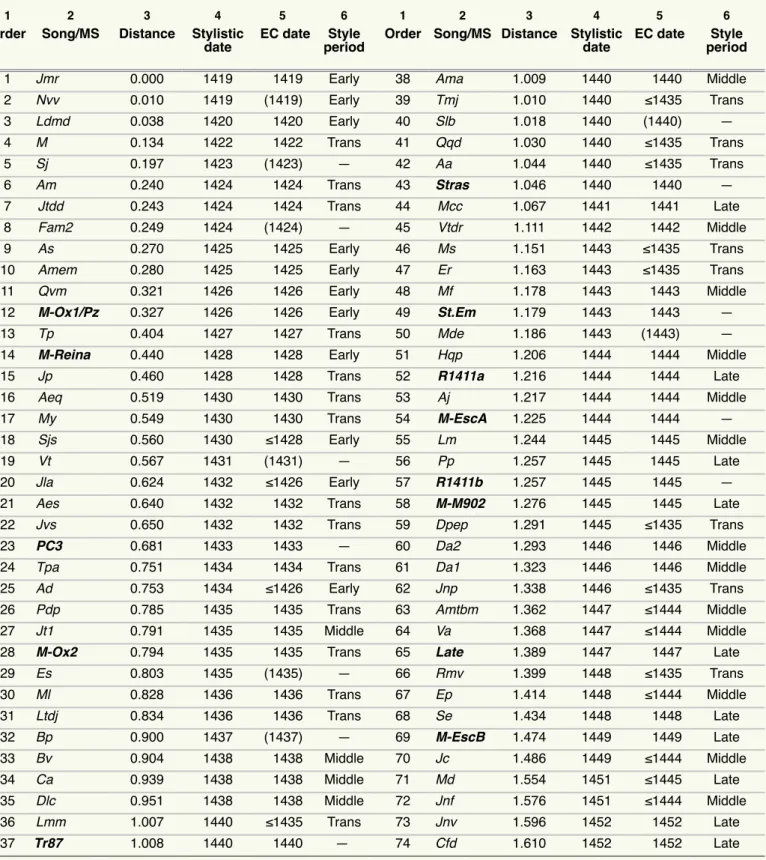

The Early, Transitional and Middle Style Periods

The Late Style Period

Taken together, this strongly suggests that M-M902 and M-EscB represent two separate parts of Binchois's late style period, which itself is a development or refinement of his middle style period. Moreover, any counterargument that the late style period covers a smaller area than the middle style period is shown in Figure 6, showing that the trends exhibited during the transition period from early to mid songs remain in force thereafter.

Finally, the fusion of M-M902 and M-EscB delineates a late style period that is a refinement or concentration of his earlier middle style period (represented by M-EscA).

Songs in EscA

Here, not only is the late barycenter closer to the barycenter progression than the M902 and M-EscB centroids, indicating that it is more in line with the general trend, but also the area of the configuration it occupies is smaller than that of M- EscA. indicating less variability in the dyadic-melodic variables; That is, the internal consistency of the findings described above and their remarkable degree of agreement with the musicological literature strongly suggest that the MDS configuration of Binchois's songs could be used as a basis for future research. The mean values of the five significant MDS variables for the four style periods, based on the manuscript groups shown in Fig.

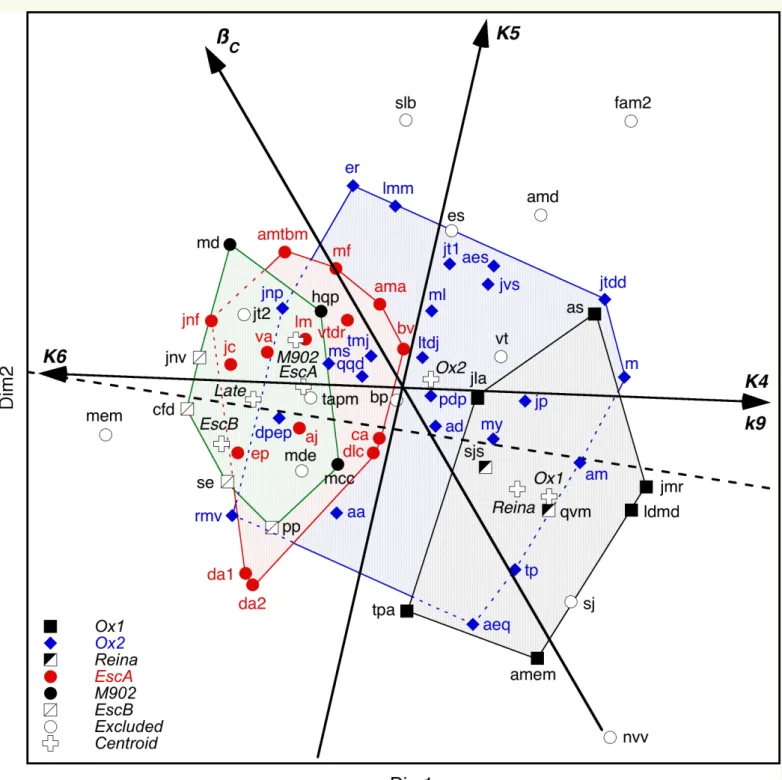

Finally, it should be noted here that the position in the MDS configuration and the EC date of the M-EscA centroid are almost certainly correct, since the four poems copied by scribe B that are distant from the M-EscA region were excluded from the M-EscA centroid calculation. EscA (B-Jvs and B-Lmm due to their M-Ox2 assignment and B-Sj and B-Slb due to their unrepresentative positions in the MDS configuration).

Songs in Tr87

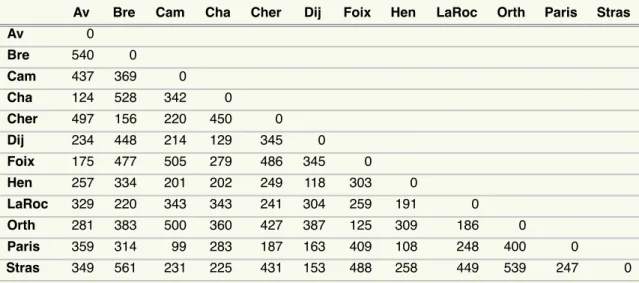

Regarding the St.Em manuscript, Slavin observed that "with the exception of two uniques [B-Amd and B-Mem, both excluded from the analysis], there is a repertory coherence in this collection [of Binchois songs]. Figure 10 , which shows the songs copied by the scribes of St. Em, confirms Slavin's observation as much as possible. Moreover, the close correspondence, with one exception, between the order of copying the songs of Binchois in St. Em (Rumbold and Wright and the dates their stylistics (see Table 6, columns 1 and 5) strongly suggests that Binchois' songs reached the scribes of St. Em. more or less in order, and perhaps soon after, he composed them, a situation which agrees with the conclusions of Rumbold and Wright (2009: 39 ff., 73) that the repertory source for St.Em was 'cultural connection'.

The copy order of the numbers in St.Em, along with their stylistic data from Table 4, column 4.

General Conclusion

Fourth, while sets of songs composed over long periods of time or from periods of rapid stylistic change in a composer's output will tend to occupy larger areas in the configuration than those composed over short periods of time, it should be presented external evidence to decide between the longer ones. explanations of time span or rapid stylistic change for their larger areas. Finally, it should be noted that, when included in the dataset on an individual basis, all of Kemp's (1990) class I and class II anonymous songs in EscA occupied positions in the M-Ox2 and M-EscA regions of the song central. group without external data. That is, they were indistinguishable from Binchois' songs, a situation almost certainly due to Binchois and the anonymous composers at EscA sharing a common harmonic and melodic language that was in vogue at the Burgundian Court27.

While the only anonymous EscA songs examined here were those in Kemp's Class I category and included in the working list of songs in the Binchois studies, future researchers using the analytical framework used in this study would not may only scan the datasets for problematic and misattributed poems, but also be careful in the initial selection of works and only include them in the analysis with good reason (eg based on style, attribution, text, etc.).

ENDNOTES

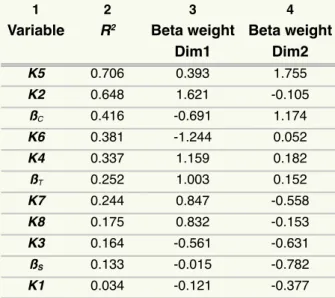

This R2 value not only resulted in a meaningful set of vectors, but also corresponded to a gap in the R2 values between K4 and βT (see Table 2). When this is done, all three appear to have positions in the same region of the MDS configuration as B-Tapm: the lower left region of the configuration delineated by the K6 and K5 vectors (not shown). Finally, it should be noted that the boundaries between the style periods are porous, with no abrupt changes in style, as evidenced by the gradual changes in the dyadic-melodic variables that occur over time and the style period in Figure 1.

6 and the marked degree of overlap between manuscript group regions in the MDS configuration in Fig.

APPENDIX

Of the seven M-Ox2 songs in W that are either in or near the M-Ox1 region of the configuration, five are in fascicles IIIz (B-Am, B-Jp, B-Jtdd) and IIy (B-Aeq ) found , B-Nvv) from Ox, the exceptions being B-My and B-Tp (see Fallows 1995). This common harmonic and melodic language may be a result of the use of compositional models, stock phrases and previously memorized melodic formulas in written composition (see Berger Canguilhem Rossi 2005). EscA El Escorial, Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo del Escorial, Biblioteca en Archivo de Música, MS V.III.24 EscB El Escorial, Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo del Escorial, Biblioteca en Archivo de Música, MS IV.a.24 Lab Washington DC, Library of Congress, Music Division, MS M2.1.L25 Case ('Laborde Chansonnier') Mel New Haven, Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, MS 91 ('Mellon Chansonnier') M902 Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Cod.

Discussion of the Authorship of B-Lmm

The occurrence in Grossin's Tres douchement, B-Lmm, and B-Sjs of three musical features described by Slavin as "unparalleled" in and "outside Binchois's usual practice": a rising leap of a fourth between two first notes (1), a rest that interrupts the cadence at the end of the first phrase (2), and the cadential figure in the penultimate bar (3). A1 provides no support for its authorship, we can see that Slavin's case for Grossin's authorship of B-Lmm is not as watertight as it might at first appear. Consequently, since the evidence reviewed here not only weakens Slavin's case for Grossin's authorship, but also provides no evidence to contradict and, in fact, supports its attribution to Binchois in Ox, B-Lmm is provisionally assigned to Binchois and is included in M-Ox2. and its central reckoning until further evidence emerges to decide the case.

POSTSCRIPT

Example A1 from the appendix has been redrawn to show the occurrence in B-Lmm, B-Sjs and Se mesdisans of four common musical features (see text).

Burgundian court song in the time of Binchois: Anonymous Chansons of El Escorial, MS V.III.24. Histoire de la Musique et des Musiciens de la Cour de Bourgogne sous le Règne de Philippe le Bon. Dating the Trent Codices from their Watermarks, with a Study of the Local Trent Liturgy in the Fifteenth Century.

Musik am Oberrhein im Spätmittelalter: Das Straßburger Manuskript, olim Bibliothèque de la Ville, C.22'.

ABSTRACT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR