As with all CAEPR publications, the views expressed in this Discussion Paper are those of the author(s) and do not reflect an official CAEPR position. Jon Altman is Professor and Director of the Center for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR), Australian National University (ANU), Canberra. Secondly, there is no doubt that some of the most persistent development, housing and infrastructure problems facing remote Indigenous communities are apparent in the Northern Territory.

There has been escalating media coverage of the view that Indigenous economic disadvantage and housing and infrastructure shortages are linked to communal ownership of land as a result of land rights and Indigenous title. This report examines the extent to which individual ownership of land is likely to enhance the economic development of Aboriginal land and provide better housing outcomes by examining the provisions of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cwlth). Territory) Act 1976 (Cwlth) Territory) Act 1976 (ALRA).

Introduction

Many have severe housing shortages and much of the existing housing stock is in poor condition (Taylor 2004). Much of the current debate began with a call to amend the Land Titles Act to allow communally owned land (groups of traditional owners) to be sold under inalienable title. A comprehensive review of the ALRA by John Reeves examined the issue of the apparent failure of land rights to deliver development (Reeves 1998).

The Legal Framework

There is a tripartite relationship between traditional owners, land trusts and land councils under the ALRA. However, the ALRA recognizes another important aspect of Aboriginal tradition: multiple, overlapping rights to different areas of land. There are many residents of communities on Aboriginal land in the Northern Territory whose traditional rights to use the land do not extend to decision-making on the development of ALRA land.

Grants of interests in land for longer periods require the consent of the Minister responsible for the ALRA or his or her delegate where permitted. The further consent of the land council is required for any trade in granted interests. The ALRA requires the Commonwealth to pay into the ABA money from Consolidated Revenue equal to the royalties paid to the Crown for mining on Aboriginal land in the Northern Territory.

The extent of ministerial power to control land deals under the ALRA is staggering. The 1998 review of the ALRA (Reeves 1998) was the first to recommend substantial changes to land tenure structures and the end of the consent and approval role of the Minister for Land Relations. These include the power to override the decisions of land trusts and land councils and the power to appoint the chair of the ABA.

While the land is owned for the benefit of the traditional owners, the services provided by the state are for the benefit of all residents, indigenous and non-indigenous.

Housing on Aboriginal Land

The inadequacy of the housing stock in remote Indigenous communities has been well documented (eg Jones 1994; Neutze, Sanders & Jones 2000; Northern Territory Government 2004). Furthermore, the rate of depreciation of the housing stock in remote areas is very high. This land was primarily pastoral tenure and could therefore have a higher economic value than much of the land held under the ALRA, particularly in the dry zone.

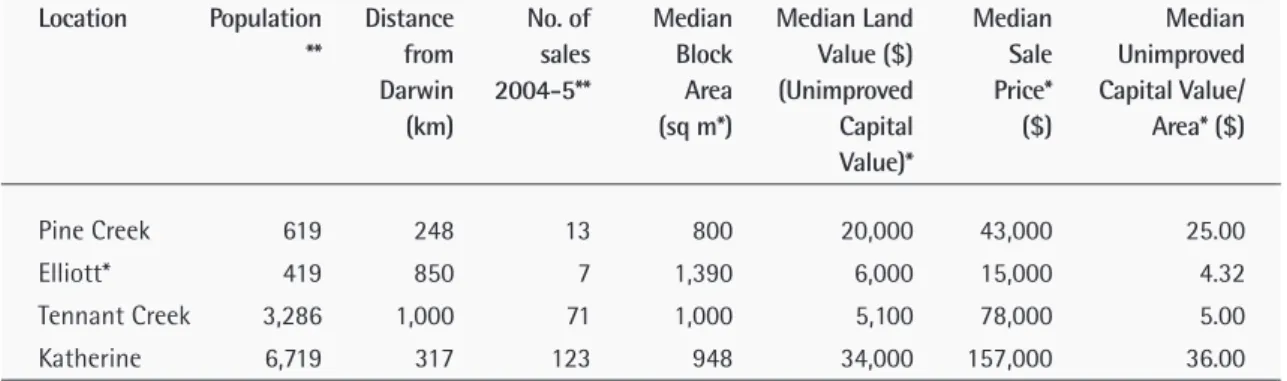

Another indication of the possible value of the land and the depth of the real estate market can be obtained from house sales in some of the smaller and more remote towns of the Northern Territory (not on ALRA or native title land). For Elliott, data for the period 2003 to 2005 is used due to the small number of sales per year. One possibility is for governments (Territory or Australian) to continue to fund the building and maintenance of the required homes.

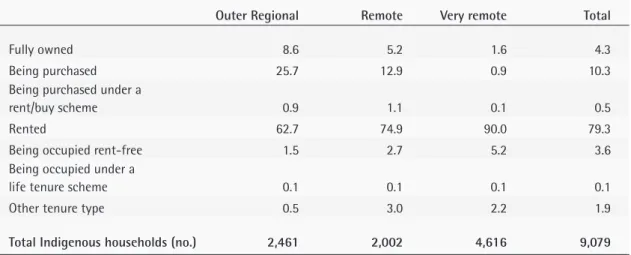

A variation of a hire-purchase arrangement that takes into account the accumulative equity interest held by the borrower in the asset may be appropriate. By sustainable we mean that a housing association's income from all sources covers the replacement costs of the housing stock it is responsible for. In our view, it is unlikely that current rents will be sufficient to finance more than a modest proportion of the costs of building replacement housing.

However, this may be an appropriate rental level given the low quality of much of the housing stock (Northern Territory Government 2004).

Economic development

Such an investment pattern is also likely partly due to the nature of investment opportunities in the context of low population density, low average income and low agricultural value of the land. There are indications that this is indeed the pattern of investment taking place, with a relatively large number of mines being established on Aboriginal land and land being leased for the construction of the Alice Springs to Darwin Railway. The ABA's net accumulated assets of an estimated $100 million are ultimately controlled by the Secretary of Immigration, Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs.

Aboriginal people want control of the ABA and have made this clear since a review of the Aboriginal Benefit Trust Account in 1984 (Altman 1984). Of particular importance is the decision to maintain the ABA's equity at an arbitrary minimum of . In 2005, this finding seems to contradict the strong performance of the mining sector and the large number of exploration deals on Aboriginal land in recent years (ABA.

When examining the breakdown of payments under the various sections of the ABA, it is clear that grants intended for or for the benefit of Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory are extremely low (on average under $5 million per year) when considered against the $100 million dollars. accumulated surplus. It also becomes clear that significant amounts of the ABA's income are allocated to meet its administrative expenses, a practice that only began in the late 1990s. In terms of economic development, the status of the ABA raises a series of important issues.

Of great importance in the current policy debate is to hear a diversity of Indigenous perspectives on economic development and to explore all possible avenues for appropriate and sustainable development on Aboriginal land, so that the mistakes of the past are not repeated.

New Zealand experience of housing on communal land owned by Mãori

The situation becomes more complicated when ownership is widespread and only some owners live on the land. The test for any partition is that the court must be satisfied that the partition is necessary for the efficient operation, development and use of the land. Where the land is Māori freehold and the lease is for three years or more, the Registrar of the Māori Land Court must record the lease in accordance with the 1993 Act.

An occupation order entitles a landowner to the exclusive use of part or all of the land as a place of residence. Such license is negotiated between the trustees and the applicant and recorded by the Registrar of the Mãori Land Court. The private owners of a mill near the village, Carter Holt Harvey, owned a number of houses on plots of land leased from the state.

The government decided to return ownership of the entire town to Ngãti Whare for free. At the time of the handover, the Forest Service village's assets were not well maintained. The title was held by the Mãori Land Court in an ancestor of the iwi in trust.iwi in trust.iwi 29 The trustee administrators leased the land to a trading company.

Around the time of the return, about 94 percent of the villagers were of Mãori descent.

Summary and Recommendations

Residents of houses got a new landlord after returning, the trading/administrative arm of the Ngãti Whare tribe. Aboriginal land covers almost 50 per cent of the Northern Territory and over 70 per cent of the Northern Territory's Aboriginal population live on Aboriginal-owned land. It is not the first time the ALRA has come under scrutiny since the election of the Howard government in 1996.

For Aboriginal communities, there has been a history of under-provision in a context of rapid population growth and relative population stability, with more than 70 per cent of the Northern Territory Indigenous population living on Aboriginal land. Examining economic development on Aboriginal land requires adapting mainstream assumptions to address the challenges of remoteness and the low commercial value of much of this land, and to take into account the aspirations of Aboriginal landowners. Many of the existing contributions to the debate are from people who seem to have little direct experience of remote situations;.

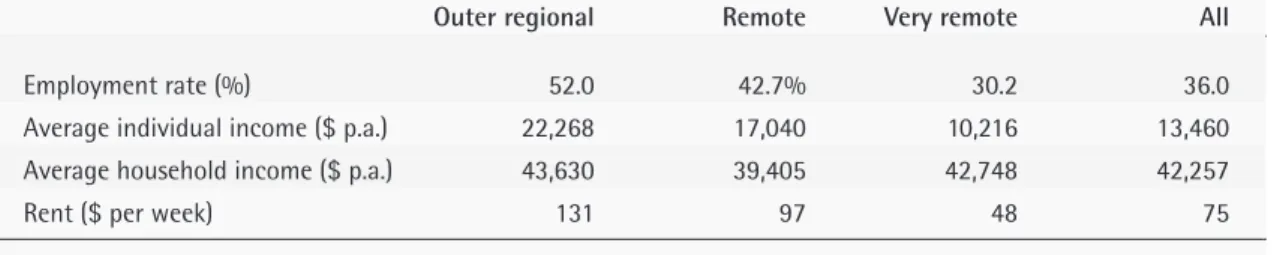

In addition to low employment and income rates, there are a number of other factors that are likely to make it difficult for Indigenous people in remote areas of the Northern Territory to get a loan from a commercial lender. Report on the Review of the Aboriginal Benefit Trust Account (and Related Financial Matters) in Land Rights Legislation in the Northern Territory, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra. State of Australia's Environment 2001, Independent Report to the Commonwealth Minister for Environment and Heritage, CSIRO Publication on behalf of the Department of Environment and Heritage, Canberra.

Unlocking the Future: The Report of the Inquiry into the Reeves Review of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Administration: Client Service Performance of the Mãori Land Court Unit and the Mãori Trustee, New Zealand Government, Wellington. Building land rights for the next generation: the review of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, Canberra.