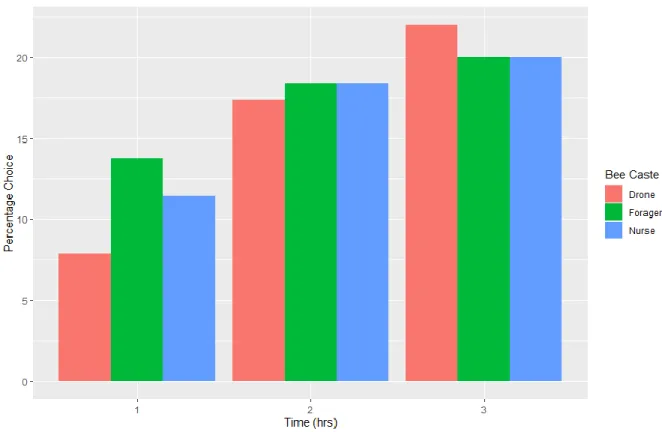

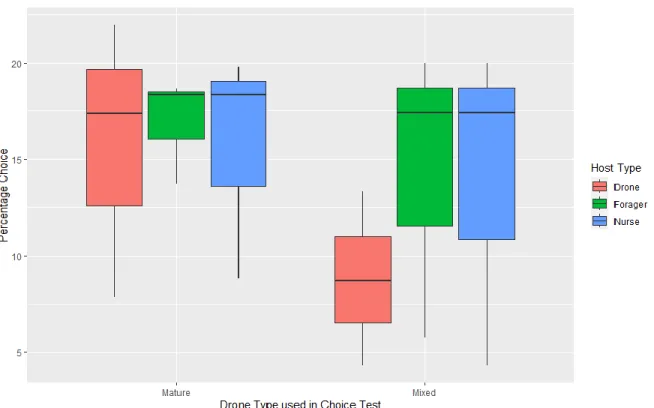

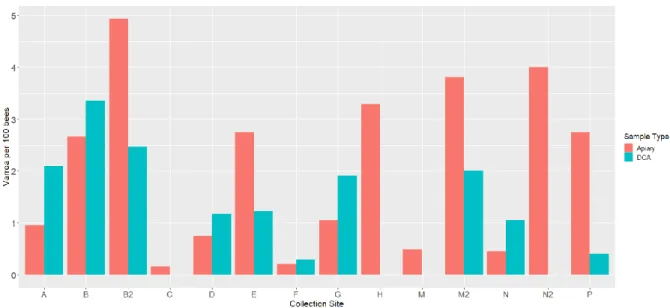

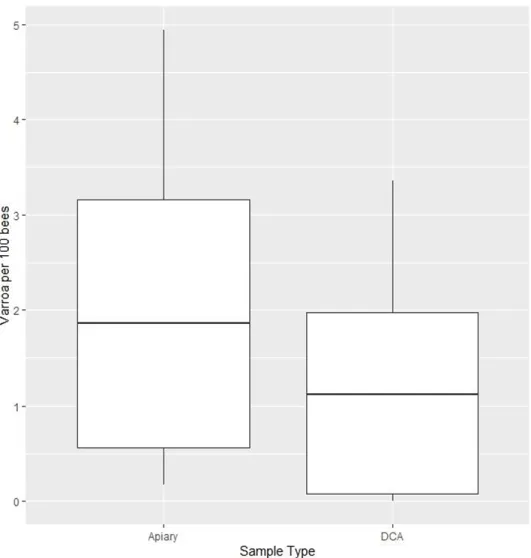

The rapid international spread of the parasitic mite, Varroa destructor, has played a central role in colony health. Varroa destructor selected drones as hosts in equal proportions to foragers, suggesting that drones are important phoretic hosts for the spread of V. There was also a significant positive association between DWV abundance in drones and DWV abundance in colonies closest to the apiary .

Thank you for taking me on, and being so passionate and enthusiastic about my project. I would like to thank the team at dnature for analyzing the viruses in my bee samples. Many thanks to Phil and Antoine for sharing your R script to help me with my data analysis, and to Sacchi and Gonzalo for your advice on developing a choice test.

Thanks to all the family and friends who have supported me in this endeavor. Thank you to Toby for being my environmental science buddy to the very end, and thank you to Daniel for being such a constant support and encouragement over the past few stressful months.

Literature Review

Therefore, strategic and effective use of miticides is both economical and beneficial to honey bee health. Drones are either excluded from the colony at the end of the mating season or die immediately after mating with a queen (Page Jr & Peng, 2001). Varroa destructor monitoring is an important beekeeping practice, but one that is often neglected due to limitations in current methods.

In this thesis, I want to investigate the role that honey bee trotters play in the spread of the parasite V. Since bees carry 2-3 times more trotters than workers (Free, 1958), I hypothesize that V. destructor will choose trotters as phoretic hosts. The Destructor chose drone hosts and foragers in equal proportion. destructor chose drones as hosts significantly more often when the available drones were adults rather than randomly selected colony drones. Varroa destructor depends on honey bees, Apis mellifera, for both intra- and inter-colony spread, but both must be met for spread, and V. destructor depends on different behaviors of their immediate host bee.

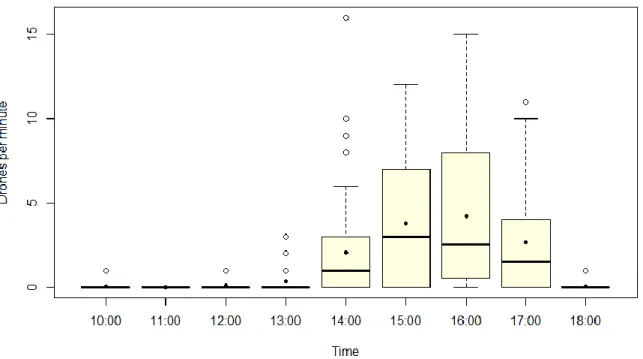

Varroa destructors were stored in a glass petri dish at room temperature for no more than three hours before the start of the tests (Singh et al, 2020). All three of these variables are related to the reproduction of the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) for which timing is a crucial element. In this chapter, I aim to explore the potential of DCAs for monitoring honey bee health at the population level and expand on our current knowledge of the role drone honey bees play in the spread of honey bee parasites and pathogens.

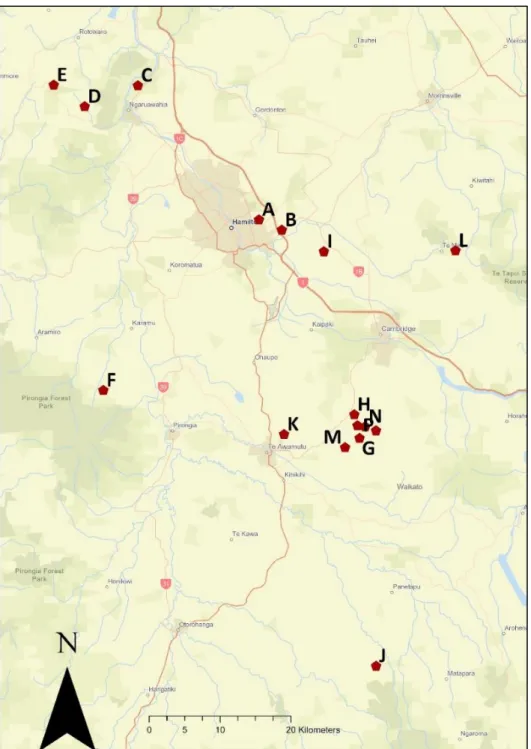

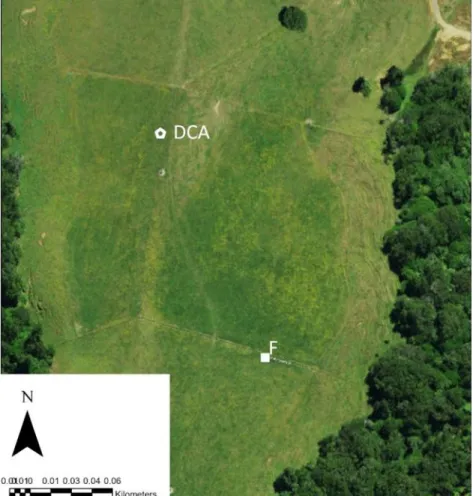

While workers represent a higher proportion of the total individuals in a colony (Seeley & Morse, 1976), drones express a higher frequency of drift than workers (Free 1958). Varroa destructors have been detected on drones at DCAs (Mortensen et al, 2018) and Peck and Seeley (2019) noted that drifting drones represented an average of 21% of drones entering monitored hives. Map of the distribution of the paired study sites in the Waikato region of Aotearoa-New Zealand.

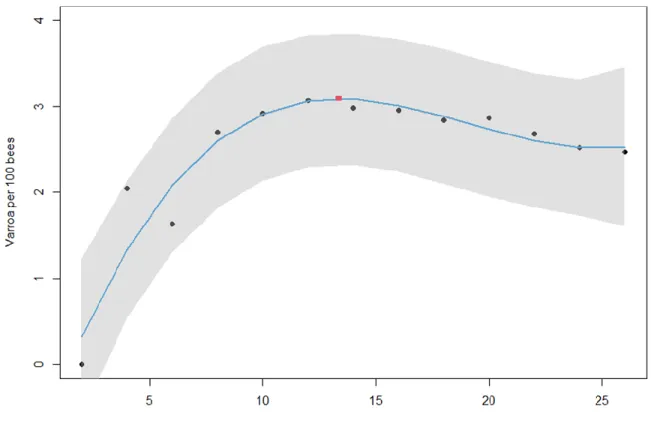

A live queen honey bee was suspended from the bottom of the trap as pheromone bait. Poisson generalized linear model of the Varroa destructor infestation rates of paired DCAs and nearby bees. However, there was a significant, positive relationship between DWV viral copies in drones compared to colony bees, which I suspect is a product of the vector relationship between V.

Williamson et al (2022) found that genotyping drones captured at a DCA is a viable method for estimating honeybee density in an area, and that their sampled DCAs contained drones from two-thirds of the known wild population. In addition, mixing drones from different colonies and apiaries at DCAs could 'dilute' DWV infection from the DCA.

Conclusion

Apparent virus infections and their interactions in pupae of the honey bee (Apis mellifera Linnaeus) in Australia. World honey bee health: the global distribution of western honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) pests and pathogens. The removal of hacked drones: an effective way to reduce varroa infestation in honey bee colonies.

Do dispersal mechanisms alter the host–parasite relationship and enhance virulence of Varroa destructor (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) in bee colonies (Hymenoptera: . Apidae). The population growth of Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) in bee colonies is influenced by the number of foragers with mites. Varroa destructor parasitism and genetic variability in honey bee (Apis mellifera) drone collection areas and their association with environmental variables in Argentina.

Viral communities in the parasite Varroa destructor and in colonies of their honey bee (Apis mellifera) host in New Zealand. The use of drone capture and drone releases to influence the mating of European queens in an African honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) area. The roles of locomotion and predation in the transmission of Varroa destructor from collapsing bee colonies to their neighbors.

The effect of DEET on the chemosensation of the honey bee and its parasite Varroa destructor. The use of trapped drones to determine the density of honey bee colonies: a simulation and empirical study to evaluate the accuracy of the method. Evidence of the synergistic interaction of honey bee pathogens Nosema ceranae and deformed wing virus.