56

Adirama Med.l IndonesSmoking problem

in

Indonesia

Tjandra

Yoga Aditama

Abstrak

Kebiasaan merokok merupakan masalah kesehatan penting di Indonesia. Sampai 60Vo

pria

Indonesia dan sekitar 4Vo perempuan dinegara kita punya kebiasaan merokok. Kadar tar dan nikotin beberapa rokok kretek ternyata

juga

cukup tinggi. Selain dampak kesehatan rokok juga punya dampak buruk pada ekonomi, baik tingkat individu maupun keluarga. Dari sudut kesehatan, kendati data nrorbiditas dan mortalitas berskala nasional sulit didapat, data dari berbagai kota menunjukkan timbulnya berbagai penyakit akibat rokok seperti kanker paru, PPOK, gangguan pada janin dan sebagainya. Masalahnya lagi, kebiasaan merokok telah dimulai usia sangat muda di Indonesia. Pada tulisan ini disampaiknn juga hambatan-hambatan dalam program penanggulangan masalah merokok serta hal-hal yang perlu dilakukan untuk meningkatkan program penanggulangan yang ada. (Med J Indones 2002;l1:

56-65)Abstract

Smoking is an important public health probLem in Indonesia. Up to 60Va of male aduk population as well as about 4Va of female adult population are smokers. In fact, some of Indonesian kretek cigarettes have quite high tar and nicotine content. Besides health effect, smoking habit also influence economic status of the individuals as well as the family. In heahh point of view, even though reliable nation wide morbidity and mortality data are scarce, report from various cities showed smoking related diseases, such as Lung cancer, COPD, effect of pregnancy, etc. Other problem is a

fact

that smoking habit start quite in early age in Indonesia. This article also describe factors complicate smoking controL program as well as several things to be done to strengthen smoking controL progrant itt Indonesia. (Med J Indones 2002;II:

56-65)Keywords : smoking, I ndonesia, impact

The

Republic

of

Indonesia,

which consists of

approximately

17,000 islands, had apopulation

of 210

million;

it

is

the

fourth

most populous country

in

theworld atter

China,

India,

and

the United

Stateswith

hundreds

of ethnic groups and

language

/

dialectsbeing practices

in

the

country.

An

estimated

55.4million

persons(3lVo

of the

population)

were livingin

urban areasin 1990, compared

with

73.4

million

(36Voof

the population)

in 1997.t'23

All

of

these

factors complicate tobacco-control measuresin

Indonesia.Smoking

Pattern

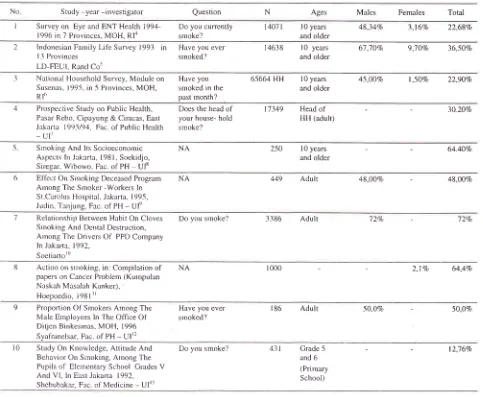

Table

I

compiles

the

results

from

several studies

onsmoking behavior

in

Indonesia. The

percentage

of

current smokers among males

rangesfrom

30.2Vo toPuLmonology Department Faculty of Medicine University of I ndo ne s ia / P e r s ahab atan H o sp ital, J aknrta, I ndone sia

72Vo,

with

the

highest percentage belong

to

thedrivers

of public

buses

in

Jakarta.Among tèmales,

the percentage rangesfrom

I .5Voto

9.1Vo.The

Indonesian

Smoking Control Foundation

('LM

3")

compiled

a

meta-analysis

study

on

smoking

patternsin

Indonesia. laThe conclusions

of

the

meta-analysis studyperformed

by

"LM3"

included

the following:rl1.

The studies

found that

59.O4Voof

males over

ten yearsof

agein the

14provinces

in Indonesia were

currently

smoking.

Among

femalesover

10 yearsof a5e,4,837o were

culrent

smokers.2.

There was a negativecorrelation

betweenthe

level of education and the percentage of current smokers.3.

On

average,

cullent

male

smokers consume

almost

ten

cigarettes each

day, while

femalecuffent

smokers consumearound three

cigarettesVol. I I , No

l,

January-

March 2002 Smoking problem inIndonesia 5j

4.

Among both current

and

former

smokers,

males 7.

Clove-flavoured cigarettes

(kretek)

were the

or

females,

the fiequency

of

smoking was

still

favourite choice

of

smokers

in

Indonesia.

Forfairly mild,

less than

200

score indexed

by

male current smokers,

84,3l%o preferred

kretekmuftiplication of

number

of

cigarettes andlength

cigarettes,as

did'79,42Voof

the female smokers.of

smoking.

Similar

figures were

found in former

smokers, as5.

Ex-smokers generally reported smoking

higher

84,31Voof

the males and

7294Vo

of

the

femalesnumbers

of

cigarettes

than current

smokers.

In

preferred the clove cigarettes.males

it

was

13versus

l0

cigarettesdaily,

andin

8.

For both current

or

former

smokers,

the

age

of

fèmales

it

was more significant at 6.2

versus

3

smoking

initiation

were

quite

young.

Femalescigarettes

daily.

tend to start to smoke at the older age.6.

The

averageof

ouncesof

tobacco

per

week

was0.79 in current

users, andI.42in

ex-users.Table

L

Percentage of Current Smokers in some studiesin

IndonesiaNo

S tudy -year-investigator

Question

N

Ages

Males Females

TotalI

Surveyon EyeandENTHealth1994- Doyoucunently

1407 Il0years

48,34Vo 3,l6Vo

22,68Vo 1996 in 7 Provinces, MOH,Rl4

srnoke? and older2

lndonesian Farnily Life Survey 1993in

Have youever

14638 l0 years

67,7OVo 9]0Vo

36,50Vo I 3 ProvincesLD-trEUl. Rand Co'

srnoked?

3

National Household Survey, Moduleon

Haveyou

6-5664HH

l0years

45,00Vo

I,50Eo

22,90Eo Susenas, 199-5, in -5 Provinces,MOH,

smoked inthe

and olderRl6

past lnonth?4

Prospective Study on PublicHealth,

Does the headof

'17349

Headof

3020VoPasar Rebo, Cipayung & Ciracas,

East

your house-hold

HH (adulQ Jakarta 1993/94, FacolPublicHealth srnoke?

-ur

and older

5

Smoking And ltsSocioeconornic

NA Aspects In J;rkarta, 1981, Soekidjo,Siregar, Wibowo. Fac. of

PH

UF2-50

l0years

64.40Voand older

6

Eifèct On Sntoking DecemedProgram

NAArnong Tlre Srnoker -Workers ln

St Carolus Hospital, Jakarta, I 995, Judin. Tanjung, Fac of PH

-

Ul'r7

Relationship Between Habit OnCloves

Do yousrnoke?

3386 Adult

72Vo

-

12VoSrnoking And Dental Destruction, Arnong TIre Drivers

Of

PPD Company ln Jakarlr, 1992,S oetiartor0

449 Adult

48,00Vo -

48,NVo8

Action on smoking, in: Comprlationof

NA papers on Cancer Problem (Kumpulan Naskah Masalah Kanker),Hoepoedio, l98lrl

9

Ploportion Of Srnokers ArnongThe

Have youever

186 Adult

50,0Vo -

50,OVoMale Ernployees ln The OfÏce

Of

smoked? Ditjen Binkesrnas, MOH, 1996Syalranelsar, Fac. of PH

-

UIr21000

2,17o

64,4Vol0

Study On Knowledge, AttitudeAnd

Do yousmoke?

431

Crade5

l2,76VoBehavior On Srnoking, Among

The

and 6Pupils of Eletnentary School Crades

V

(primaryAnd V[, ln East Jakarta

1992,

School) [image:2.612.50.533.294.691.2]58

AditamaThe

above datashow

no significant

differences

when comparedwith

theWHO

(1997) estimation, where in

Indonesia

the

prevalence

of

current smokers

wasreported

to be

53.0Voof

the males and

4Voof

the fèmales.But

it

should

be notedthat

theWHO

figures

werefor

people over the ageof

15 years.r-tThe

Indonesia Household

Health

Survey

in

1980 showedthat

about 54Voof

males and about 37oof

the f'emalesover ten years

of

age were regular

(daily)

smokers.

A

similar

survey carried

out

in

1986reported simrlar prevalence

rates (537oof

males, 4Voof

fèmales).Other

surveyscarried

outduring

he 1980sin

Lombok,

Jakarta,

and Yogyakarta

reported

maleprevalence

levels

of

75Vo, 65Vo,

and

67Vo,respectively, and

female

prevalence

levels

less

than 5Vo (exceptfor

Jakarta

where 9.8Voof

the females aresmokers).

Nationally, the

prevalence

of

smoking

isapproximately

607ofor

men

and 5Vofor

women.'7According

to

a

1985 survey

in

Semarang,

36Voof

doctors smoked, asdid'l9Vo of

paramedical personnel.Almost

all

(96Vo)of

the "peddle

rickshaw"

drivers

inthe

survey

smoked,

as did

over

half

(527o) of

governmentcivil

servants.A

1992survey

of

medical stuclentsrevealed

that 8Voof

males

and lVoof

femalèswere

daily

smokers,

while

39Voof

males

andl5Vo

of

females were occasional smokers.The Indonesian Household

Health

Surveyin

1995 wasone

of

the

biggest health survey

performed

in Indonesiawith

over

200.000 respondents.oAmong

itsfindings

were thefbllowing:

l.

The prevalenceof

smoking

in

the malepopulation

(10 yearsold

and above) were 457o(daily

smoker), 6.3Vo (occasional smoker) and 3Vo (fbrmer smoker).For the fèmale population, the figures were

l.5Vo, 0.57o and 0.270, respectively.2.

For

people

20

years

of

age and

above,

61 '27owere regular smokers,

and'7 .5Vowere

occasionalsmokers.

The

prevalence

in

urban areas

washrgher

than

the rural

areas,

and the

prevalence decreasedwith

higher

levelsof

education.3.

For

20 year old and

above,

4l.8Vo

of

the respondentsconsumed

1l-

20

cigarette

per

day, and 5.3Voconsumed

more that 21

cigarettes

per day.On

average, 3.9 cigarettes were consumedby

a smoker per day,or

1,421 cigarettes per year.4.

ln

urban

populations, 12.l7o

of

the

respondentsconsumed

filtered

cigarettes, 3Vo

non-filtered

c i garettes, 59 .8Vo smoked kr e t ek ci gat ettes, 20.8VoMed J Indones

smoked non-filtered

kretek

cigarettes,

O.3Vaconsumed cigars, 3.8Vo

rolled their own

cigarettes,and 0.17o smoked tobacco using

a

pipe.

Thecomparative numbers

for

the

rural

population

areas

follows:

11.6Vo, 2.8Vo, 33|7Va, 24.9Vo, O.6Vo,25 .4Vo and O.5Vo respecti vely.

Most

of

the tobacco

consumedin

Indonesia

is

in

theform

of

cigarettes, and between

85Vo and 90Voof

all

cigarettes smoked

in

Indonesia

are

kreteks.

The cigarettemarket

shareof

kreteks increasedfrom

about 30Voin

1914

to

about

90Voin

the

1990s. Since

theearly

1970s,

the per-capita adult (over 10 years of

age) consumption

of

cigarettes

(all

forms)

has

morethan

doubled,

from

500

to

I 180 per adult.

A

surveycarried

out

in

Jakarta

in

1981

estimated

that

eachsmoker consumed

(on the

average)twelve

cigarettes eachday.

About

5Voof

all

smokerssmoke more

than 20 cigarettes a day.Table 2. Consumption of manufactured cigarettes

Tar

levels

in

domestically

grown

Indonesian

tobacco arehigh.

In

1983, the average tarcontent

of

18 brandsof

kretek

cigarettes

was 58.0

mg

(range

41

-

11),while

the averagenicotine content

was2.4

mg

(range1.3

-

3.2).

These are substantially

higher

than

levelsusually

found

in

industrialized

countries.

About

73Voof

manufactured

cigarettes arefilter-tipped.r6

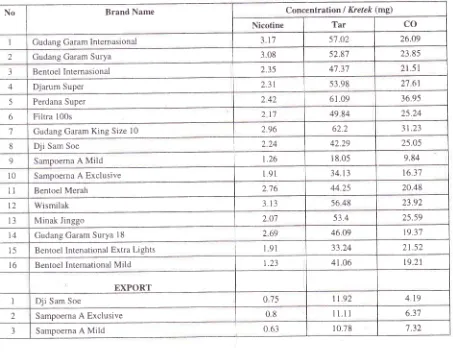

Table 3

shows

the tar, nicotine and

Carbon

Monoxide

(CO)

content

of

somekretek

cigarettesin

Indonesia.

It

isparticularly

interesting

to

compare

lhe

difTèrences inthe levels

of

the

domestic and exported products

of

the same brandsof

cigarettes.Production

and

Economic Impact

In

1990, 183,785

hectaresof

land were

set

asidefor

tobacco farmrng,

which

was down

from

288,000 hectaresin

1985.

Between lVo

and 2Voof

all

arableland

in

Indonesia

is

used

to

grow

tobacco.

Between1990

and

1992, Indonesia

grew approximately

2.OVoof

all

the

tobacco

in

the world.

In

1994,

Indonesiaproduced

about

180,000

million

cigarettes

(about-Vol I

l,

No 1, January-

March 20023.3Va of

the

world's

production),

which

wasup from

83,900 cigarettes

in

1980.

This

increase

in

cigaretteproduction is Iargely

a

reflection

of

the

dramaticincrease

in

the production

of

machine-made

kretekIn

1992, Indonesia imported 21,650

tons

of

rawtobacco

(accounting

for

l.4Vo

of all

imports), while

exporting

18,900tons (about

l.lVo

oTglobal exports)'

Indonesia

imported

15million

cigarettes and exported 15,000million

cigarettes,

or

2.27oof

global

exports.Table 3. Tar, nicotine and CO content of kretek

Smoking problem in

Indonesia

59In

1990,

the

costs importing

tobacco

leaf

andcigarettes amounted

to

US$ 42.1

million

(O.lVoof

all

import

costs), comparedwith uS$

17million

in 1985.

In

1990, Indonesia earned

an

estimated

US$

124.6million from

tobacco exports

(0.4Va

of

all

export

earnings), upfrom

approximately US$ 48.2

million

in

1985.

On the

other

hand,

Indonesian

cigarettesproduction could be

seenin

figure 1, which

showedthe

total

production

in

the

year

2000

was23'7,206,000,000 cigarettes

a year,

while

in

1995

it

w as 204,365,000,000 a year.No Brand Name Concentration I Kretek (rng)

Nicotine Tar CO

Gudang Garam Internasional 3 l'7 5'7.02 26.09

2 Gudang Garam Surya 308 52,87 23.85

3 Bentoel Internasional 2.35 47.37 21 .51

4 Djarum Super 231 53.98 27.61

5 Perdana Super 242 61.09 36.95

6 Filtra 100s 217 49.84 25.24

7 Gudang Garam King Size

l0

2.96 62.2 3t.238

Dji

Sam Soe 224 42.29 25.059 Sampoerna A Mild r.26 1 8.05 9.84

l0

Sampoerna A Exclusive 191 34.t3 t6.37u

Bentoel Merah 276 44.25 20.48t2 Wismilak 313 56 48 23.92

t3 Minak Jinggo 207 53.4 25.59

t4 Gudang Garam Surya 18 269 46.09 19.3'7

15 Bentoel Intenational Extra Lights 191 33.24 21.52

16 Bentoel International Mild 1.23 41.06 t9.21

EXPORT

I Dji Sam Soe 075 1t .92 4.19

2 Sampoerna A Exclusive

08

11.11 6.37 [image:4.612.47.500.285.638.2]'!

[image:5.612.52.280.101.249.2] [image:5.612.55.280.427.621.2]60 Aditama

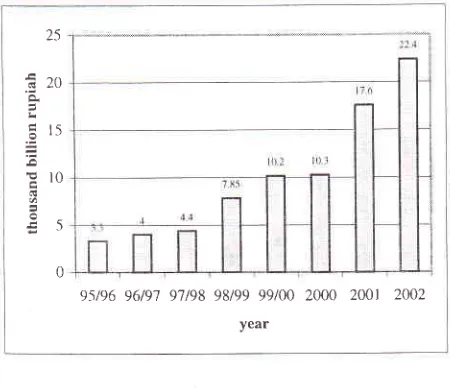

Figure

l.

Indonesian cigarettes productionAbout

214,300workers were

engagedfÏll-trme in

thetobacco-manufacturing

industry

in

1989.

The Indonesiankretek industry ranks

asthe

second largestemployer

after

the

Government.

Figure

2

below

showed

tax

fee target

from

cigarettes,

which showed

that in 1995/1996it was

only

3.3 quintillion (thousandbillions)

,

in

2000

it

was

increasedto

10,3 thousandbillions and

in

2002

iT"was expected

to

be

22,4 thousandbillions

ruprah.25

Ëzo

L

É rç

= =

Er0

l!0

95196 96/91 97t98 98199 99/00 2000 2001 2002

year

Figure 2. Tax fee target

A

study

by

the

National Institute of

Health

Research&

Development

(Ministry

of

Health)

attempted

toanalyze the

economic impact

of

smoking in

Indonesia.With the

GDP per capita

in

1995 aboutUS$ 1,100,

it

is

estimated

that

the

macro economic loss

for

theMed J Indones

country

(government perspective) was

in

the amount

of US$

9,806,423,000

(almost

10billion

US

dollars)

or

about

50Vo

of

the total

annual

budget

of

theMinistry

of Health.

Economic

losses

due

to

tobacco

at

the

individual/

family

level

can bedivided

rnto:Direct

Loss:Indirect

Loss:loss

of

income

due

to

illness

and

ordisability

cost for

medical

treatmentloss

of

income

due

to

illness

and

ordisability

loss of income due to premature deaths

loss

of

income

of

family

members,due to

taking

careof

the patientsEstimated

economic loss

at community level fbr eachlung

cancerpatient

was asfbllows:

r

Average

cost formedical

treatment-- US$

738.00.o

Average number

of

absenteeismper year due to

hospitalization --

23 days..

Thus,

thelost income

dueto illness

for one patient

is 23X

US$

5.00--

US$

I

15.00.Loss

of income

of family

members (duetaking

care of the patients) is also equal toUS$ 115.00.'e

Health Impact

Reliable national

mortality

and morbidity data

are scarce.However, whatever

data areavailable

all

point

to an increase in the

major chronic

diseases associatedwith

smoking.

Estimates suggest

that

tobacco-attributable

mortafity

has risen

from

l-37o

of

all

deaths

in

1980

to

3-4o/oin

1986.

Thrs

suggests thatabout 57,000

deathseach

year (primarily

males)

arealready attributable

to

tobacco use, and

this

number can be expectedto

increasedramatically over

thenext

few

decades.'A

studyof

COPD

andsmoking

in East Java

province

found

that

1,546

men

(60.3Vo)

were

smokers

ascompared

to only 71

(1.8Vo)of

the women.

COPD

prevalence

was

l3.l

Vooverall. In

men

it

was

15.67o,and

in

women the prevalence

was

77.3Vo. However,

among

mde

smokers theprevalence

was

15.87o. Therelative

risk of

COPD

in smokers

was 1.02.

Smoking

and

impaired

PEFR (PeakExpiratory

Flow Rate) were

recorded

in

12.47oof

all respondents,

and the

resultsof the

testing correlated

well

with the results

from the

questionnaire.Risk of

impaired PEFR

in smokers

was 240,0(x)2_r0,ux)

220,(rx)

!

zro.rxxt.* 2(X),(XX)

r 90,(xx)

I 80,(XX)

Vol 1 1, No 1, January

-

March 20021.04.

Asthma was found

in

8Voat

all respondents,

while

its

prevalence

in

men was

9.67o,

in

women 6.4Vo, andin

male

smokersit

was 9.2Vo.The relative

risk

asthmain

smokers was 0.88.All smokers smoked

cigarettes;

none

of

them

professed

to

being a

cigar

smoker

and

only

one was

a

pipe

smoker.

Kretek

cigarettes

were

the

most

widely

smoked

type

of

cigarette

(61.57o).Only

270

(l'7.5Vo)

of

the

respondents

had stopped

smoking,

but

only

154

(57Vo)had done so

for

morethan

I

year,

and

only

I2.6Vo

of

clove

cigarettesmokers

have

tried

quitting.

Most

of

the

smokers (76.6Vo)can

be classified

as

light

smokers, smoking

less

than

10 cigarettes/

day.The

numberof

cigarettesI

male smoker

/

day

comes

to

6.7

cigarettes.

Theprevalence

of

smokers goes

up

almost

linearly with

age,

being

22.47oin

the

under

20

group

to

15.67oin

the

over-S0 group. Although paradoxically

almost40Vo

of

them

started

smoking

in

their late

teens(38.5Vo)

and

more

lhan

757obegan

to

smoke

before the age of 25 (77 .2Vo).2oIn

a

study

on smoking

and

lung

cancer

in

Jakarta,it

wasfound

that the relative

risk to

getlung

cancerfor

smokers

20

-

39

yearsof

age was 6.'76, and for thosewho

had

smokeclfor

more

than40

years,the relativd

risk

was

9.37.'fhey

found a significant

relationship

between

smoking

and

lung

cancer among

their

malerespondents,

but

not

among

the

females.

The

dose-responseimpact

was also discovered to besignificantly

u-àng

their

male respondent.2lAnother survey

in

1993 assessed

effects

of

passivesmoking

on pregnancy outcomesin

Jakarta.The

studyconcluded

that

odds

ratio

for

a

pregnant

women exposed to passivesmoking having

alow

birth-weight

infants

was2.3.22Smoking problem in

Indonesia

6l

Prevalence

Among Youth

A

1985 survey

of

primary

schoolchildren

in

Jakartafound

that

49Voof

theboys

and 97oof

the

girls aged

10-14

were

daily

smokers.

However,

a

study in

Jakarta

in

1990 reported

that

only

IVo

of

the 1l-14

year

olds,

9Voof

the15 year

olds,

and

67oof

the 16

year

olds

weredaily

smokers,although

thefigures

for

occasional smokers

were

157o, 22Vo,

and

44Vo,respectively. The latter study

also revealedthat9Vo

of

the

children

startedsmoking when under

l0 years old,

\Va at the age

of

ll,

l87oat

age I2,23Vo at age 13, and40Vo

at

age

14-16.The

vast

majority

(95Vo) smokedkreteks,

and 72Voreported

that their

parents

did

not

know

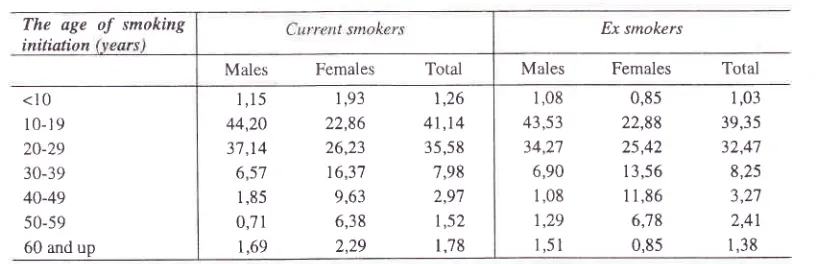

that they smoked.r3The meta-analysis study done

by "LM 3"

found

thatin

both

current

and former

smokers,

most

initiated

smoking between 10 and

29

yearsof

age; there

wasno

clear

difference between males

and females.

However,

the studydid

show thatmale

teenagers startsmoking earlier,

while

females tend

to

wait

to

try

smoking

at-terthe

age of 20,but all

were

at theyoung

group. This

was happenedin

the severity

of

smoking,which both

groups togethermajority

were

still

stay in themild

group,

l.e. less than 200.14This

study also concludedthat

teenager smokers werefound in

the proportion ranged

from

l2.8Va

to 2'1,'lVo

in

males, and among females were

O.64Voro

lVo.Either

in

current or

ex-smokers

the

age

of

smokinginitiation

were quite

young, since

the

highestproportion

wasfound

in l0

to

lessthan 30

years old.In

malesthere

were

8l,34Vo

of

current smokers,

and 77,80Vo ofex

smokers,while in

femaleslooked

likely

to

be

lower,

49.O5Voof

current smokers, and

48.30Voof ex

smokers. Femalestend

to

start

to

smoke at

theolder

age.Table

4.

The Age of Smoking Initiation among SmokersThe age

initiation

of smoking

Ex smokersMales Females

Total<10 10-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60 and up

1,08 43,53 34,27 6,90 1,08 1,29

1 ,51

0,85 22,88 25,42 13,56 1 1,86 6,78 0,85

1,03 39,35 32,47 8,25 ? ?',7 2,41 1,38

Males Females

Total1,15

1,93

1,2644,20 22,86

41,1437,14 26,23

35,586,57

16,37

7,981

,85

9,63

2,970;71

6,38

t,sz [image:6.612.84.502.582.714.2]-l

62 Aditama

The

Indonesian

Household Health Survey

1995found

that

the

youngest

ageto

start smoking was

5 yearsold.

While

afair

number

of

respondents startedsmoking between

the

agesof

10and

14 yearsof

ageor

between

21

and

25

years

of

age, most

of

therespondents

started

smoking between

15 and

l9

years

old. Only

a

very

small proportion

of

therespondents started

smoking

between

26 - 30

yearsold.6

Another survey

by

the

University

of

Indonesiashowed

that young adult men (when

compared

toyoung

adult women)

are

far

more

likely

to

usesubstances

that

increase

health risks. For

example,8l

.lVo of young adult men

have smoked

cigarettescompared

to only

8.)Voof

women.

Similarly,

21.9Voof

men say they have

drunk alcoholic

beverages(compared

to

only

7.0Vo

among women), and

ahistory

of

recreational

drugs was reportedin

8.5Voof

the men and

only

0.5Vofor

women.

In

general,

theconsumption

of alcohol

andrecreational

drug

use ishigher

among

older

respondents (aged

20-24

yearsof

age),in

urban

areas,and among the more

highly

educated.

In

contrast,

does not vary

significantly

Med J Indones

with

age, urban ys.

rural

setting, and

their level of

education.

While

menwho

have beenmarried report

higher levels

of

smoking and

drinking,

single

malesare

slghtly

more

likely

to

have used

recreational

drugs (8.6%

of

single

men compared

to

'7.2Voof

married men).

When

askedif

smoking,

drinking,

and

drug

use

areharmful activities, nearly

all

respondents

said

yes.Many young

adults

who

are

using

these

substancessay

they would

like to

stop.

Among youth who

arecurrently smoking,

83.2Vowould prefer to give

up thehabit. Young adult

smokers

who were

interviewed

are

quite

heavy consumersof

ci

arettes; men average7.6

ctgarettes andwomen

3.7ci

arettes eachday.'''

Another

survey

in

Bali

found that

15Voof

primary

high

school

students(14-15

yearsold)

are

smokers.Data

from

1219 primary

and

secondary

school

in

Bandung

(1998) showed

that

32,33Vo

had

trredsmoking,

andthat

12.3Vo aredaily

smokers.Another

survey

on

streetvendor

children

in

I998 found

that18.217o

of

those

children

are smokers

in Semarang

and 58Vo

of

themin

Bandung.2aTable

j.

Smoking attitucle2lSex of Respondent Total

Male Female

Do you thinks smoking is harmful?

Total Respondents:

Have you ever smoked?

Total Respondents:

Are you just "experimenting?"

Total Respondents:

Do you smoke now?

Total Respondents:

Do you want to stop smoking?

Total Respondents:

Have you tried to stop smoking ?

Total Respondents Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes, regularly Yes, sometimes

No Yes No Yes No 9'7.\Vo 2.2Vo 42t9 8l.9Vo 18.lVo 4221 3'7.8Vo 62.2Vo 3456 '78.2Vo 20.5Vo l.3Vo 2152 83.lVo l6.9Vo 2122 85.jVo 15.ÙVo r763 96.8Vo 3.2%

3 854

8.jVo

92.jTo

3 858

89.4Vo 10.6% 308 t'7.9% 44.40k 37.'7Vo 33 94.3Vo 5.7Vo 20 87.9% 12.lVo 19 97.3Va 2.t10 8073 46.6Va 53.4% 8079 42.1Vo 57.9Vo 3'764 77.3Vo 2O.9Vo 1.8Vo 2185 83.2Vo 16.8Vo 2143 85.OVo 15.OVo

Vol I

l,

NoI,

January-

March 2002A

survey was conducted

by the

Indonesian Smoking

Control

Foundation

("LM3")

to

determine

thesmoking pattern among children street vendors

in

Jakarta.

This

survey interviewed 250 street vendors

in

Jakarta,

all

below

14 years

of

age.

20.27Voof

thesechildren

sell cigarettes.9.57Voof

thesechildren

startedsmoking

before the

age

of

10

years,

25.36Vo startedbetween

l0 -

1I

yearsold,

52.63Vo start smoking ar 72-13 years

old and

14.447o startsmoking

at

14 yearsof

age.

Of

thesestreet vendor

children,

40.67oof

themsaid

they

planned

to

continue smoking

in

the

future.Their

reasonsto start smoking were

"for fun," it

"tastesgood," "proud"

to

be

smoker,

and

to

feel

"macho."

54.9Vo

of

the respondents consumed less

than l9Vo

of

their

income

to

buy

cigarettes,

37.74Va respondentconsumed l0-20Vo

of

their

income, 5.037o

consumed21-30Vo. 1.89Vo consumed 31-40Vo

and

1.26Varespondent consumed

more than

40Voof

their

incometo buy

cigarettes. 7'7Voof

thegroup actually

felt

afraidthat

their

parents

would learn

that their

childrensmoked cigarettes. 86.98Vo

of

them knew that smokingwas dangerous,

but only

40.60Voof

them

felt

that

hadany current health problem

related

to

their

smokinghabit.

Of

these, 71.087o experienced

coughing

and12.05V0

described

dyspnea.

About

70.91Vo of

respondents said that almost

all

street vendor children,are active smokers.2-5

Another

preliminary

non

random survey

by

theIndonesian Smoking Control Foundation

("LM

3")

focused

on

stLldentsfrom

one

of

the top-ranked high

schools

in

Jakartanamely

SMUN

8. The

respondentswere

95

students,of

which

on]ly 7.4Vowere smokers

and 6.3Vo

were

former

smokers.On the other

hand,it

is estimated

that the smoking prevalence

in

other high

schools

is

much higher

compared

to

thrs

finding.

A

similar survey was also conducted

on

senior

yearmedical

and dentist

students,

with 71

respondents;5.6Vo

of

them are

current smokers,

and another 5.6Vo'are

former

smokers.In

contrastto those

data, a surveyon

students

at a

nursing

academy

found that

only

1.lVo

of

these students areactive smokers,

and 4.3Voare

fbrmer

smokers. Lessonsin

schoolwere

felt to

bemost important source

of information

about the harmfuleffêcts

of

smoking

by

4l.5%o

of

the high

school students respondents, 48Vo medical and dentist studentsand 38.2Vo

of

nursing

academy students.This

surveywill

be continued and extended in the near future.A

survey

on

the

knowledge

and

attitudes

aboutcigarette smoking among schoolchildren

in

centralJakarta concluded that:27

Smoking probLem in

Indonesia

63l. The

basic

knowledge concerning

cigarettesmoking

of

schoolchildren

jn

the slum

and

non-slum

areasof

Central Jakarta

is

sufficient, but it

needs to be broadened.2.

Theattitude

of

schoolchildren

in

both the slum

andnon-slum areas

of

Central Jakarta

is

generallyagainst ci garette smoking.

3.

Advertisements,

through

television,

radio

andother public media

(posters, banners, billboards)

are

the

most

persuasive sources

of

information

used to promote cigarette smoking.

Efforts

shouldbe

made

to

eliminate these

media

from

theschoolchildren's surroundings, especially

in

theneighbourhood of the schools.

4.

Educational programs

on

television

and

direct

participation

by

healthcarepersonnel

are the mostimpressive

sourcesof

information

concerning

thehazards

of

smoking,

but

at the present

time,

theseaddress

only

a

very limited

audience.

Efforts

should be made

to

increase therole of

educationaltelevision

programs

and

the

use

of

healthpersonnel

asthe source

of

information

concerningthe hazards of cigarette

smoking.

5.

The roleof

friends,

families

and school teachers assources

of information

on the hazards

of

smokingis still

very limited.

Efforts

should

be

made

toincrease

the

role

played

by

thesegroups

for

themto

become

more effective

in

delivering the

non-smokrng message.

Social activities at the

schoolssuch

as

non-smoking gatherings

with

parents,teachers,

and

students

should

be

encouraged

topromote the idea

of non-smoking.

6.

Radio

and printed media are very under-utilised assources

of

information concerning

smoking

hazards.

Attractive

programs

for

children

need

tobe

designed

so

that

children

can

get

accurateinformation

about the

harmful

effects

of

cigarettes and smoking.Summary

Smokrng

is

an important problem

in

Indonesia.

Thesmoking prevalence

in

male

population is

more

then6OVo.

The relatively

low

prevalence

rate

in

female(about 5Vo)

may

be

due

to

traditional

socialrestrictions,

but

it

is

safeto

assume that the smokingprevalence

in

w_omenwill

be

increasing

in

the

nearfuture.

Up to

30Voof

male

teenagers

smoke.

Themajority of

smokers start smoking between 15 and 2064 Aditama

young

as5

years

old. Kretek

clove cigarettes

are the mostpopular type

consumedby

smokersin

Indonesia.In fact, most

of these

kretek

cigarettes havevery high

tar and

nicotine

content.At

least

five

factors

complicate smoking-controi

programs

in lndonesia

One,

it

is estimated that about

12million

people

aresupported

by tobacco-related industries. This

includestobacco

and clove

farmers,

workers

in

tobaccofactories, the

distributors,

shops andall

theway down

to the

children

streetvendors;

and one must addall of

their families. Second,

the cigarette industry

is

animportant source

of

tax

revenuesfor

Indonesia.

Theincome that the government receives

will

surely be

aimportant consideration

while

making any

policies

regarding

to smoking-control

programs.Third,

there

is

insufficient

scientific

research

onsmoking

and health

in

the

Indonesian population.

Most doctors and health professionals use literature

from

abroad

when

designing

health-educationactivities.

Discussions

with

respectful

medical

specialists

found out that there

arequite few

researchbeing

done

in

the

field

of

smoking

and

health.Furthermore,

since colrlmon infections and

tropical

diseases

are

still

very

prevalent

in

Indonesia,

they(probably understandably) receive

more attention

compared to research on tobacco and health.

Fourth, smoking

is

socially

accepted

by

mostIndonesians.

"Cigarette money"

is a

slang

phrasecommonly used

for

giving

somebody

a tip.

During

social gatherings,

in

urban as

well

as

in

rural

areas,cigarettes are

usually

served.Asking

somebodynot

tosmoke

is

still

sometimes considered

impolite

or

perhaps

even "foreign" behavior. Fifth, the political

commitment from

decision

makersin the

governmentis not yet strong enough.

To

strengthen

the

smoking-control

program

in

Indonesia, several things are needed.

First,

healtheducation

for

the

general

public

is

very important.

Many

kinds

of

public

media

must'be

used,

sincecigarette advertising

is actively using all of

them.

In

fact, the knowledge

of

the general

population

aboutsmoking

is still

quite limrted.

In

most medical

andnursing school

cuiricula,

there

areno special

classesfor

smoking

and health. Improving the knowledge

about

smoking, its impact on

health, the economy andthe many other

aspectsof

the problem would be

anMed J Indones

important

first

step

toward

an

effective

smoking-control program in

Indonesia.Secondly,

every

segment

in

the

society must

beorganized

andutilized

optimally.

Government has

aresponsibility

of

coordination

and

regulation,

andprofessional organization and NGOs can and

alreadyplay important roles in any srnoking-control

program.ln

fact,

they

can play even more effective roles

if

allowed to work in

aconducive environment.

Third, regulation and laws

in

the

field

of

smoking

should

be

enacted

and

firmly

implemented.

Theseregulations

should

at

least include policies

onadvertisement,

tar

and

nicotine

content,

defining

smoke-free area, tobacco

tax

and fiscal

issues,protection

for vulnerable groups (such

aswomen

andchildren), etc. Many

considerations

must be keep in

mind, but

in

the end,

it

is the health

of the people of

Indonesia

who

should receive the highestpriority.

Fourth, especially

for

a tobacco and clove-producing

country like

Indonesia, adiversification

of

the tobaccoindustry should

be started.

There must be a way

tofind a

smooth transition

betu'een

the

tobacco-dependent

economy

andone which is healthy. Fifth,

political commitment from

government and parliamentshould be

encouraged. They play

acritical

role in

thedecision-making process

in

the country. NGOs

andother public

organization should lobby

hard to obtain

this important

political

commltment.

Sixth, there are

still

much

to

be done

in

the

field

of

research.

Epidemiological

research must beimproved.

Indonesia

is a

huge country

with

more

than

200million

inhabitants in hundreds ethnic

groups

spreadover

17,000 islands. Specialepidemiological

techniquesare needed

to obtain

reliable data that

represents thewhole country.

The health-related economic

researchis

also needed.

"Money talks," and

having

goodinformation

will

accomplish

alot in

discussions abouteconomic

policies.

International collaboration

can,

indeed,

play

animportant

role in

smoking

control.

This

kind

of

collaboration

does

not

only cover

researches,but

it

also

servesas a

kind of

bench-marking

of

activities

between

countries

in

various

aspects

of

their

respective smoking-control programs.

Success storiesfrom

one

country

could

provide motivation

for

neighboring

countries. On the other hand, failure of

I

Vol I

l,

Nol,

January-

March 2002example

for another.

Smoking is, after

all,

a

global

problem, and

only a

global solution can

effectively

deal with

it.

Acknowledgment

The

authorwould like

to

rhanksDr John W Aldis MD

for

his

valuable advice

rn

the

presentation

of

this article.REFERENCES

i.

Central Bureauol

Statistics. Demographic and HealthSurvey I 997. Jakarta, Central Bureau of Sratistics, 1 998: I-3

2.

National Household Health Survey 1992 (lndonesian).Jakarta,

NIHRD Ministry

of

Health Republic

oflndonesia,1992

3

Internatjonal Medical Founclationol

Japan. SEAMIC Health Statistics 1998. Tokyo, IMFJ, 1998.4.

Ministry

of

Health Republicof

Inclonesia. Survey onEye and E-N-T Health 1994-1996 in 7 provinces, MOH,

RI

(lndonesian). Jakarta:NIHRD Ministry

of

Health Republic ol Indonesia, 1 996.5.

Ministry

of

Health Republicof

Inclonesia. IndonesianFamily

Lifè

Survey 1993in l3

Provinces (lndonesian). LD-FEUI, Rand Co, 1993.6.

Ministry

of

Health Republicof

Indonesia. NationalHousehold Survey, Module

on

Susenas,1995,

in

5 Provinces (lndonesian).NIHRD Ministry

of

HealthRepublic of lndonesia, 1996

l.

FKMUI.

ProspecLive Studyon

Public

Health, pasarRebo, Cipayung

&

Ciracas, East Jakarta: (Indonesian). Jakarta: FKMUI, 1993194.8.

NotoatmodjoS, Soekidjo, Siregar

KN,

Wibowo

A.Smoking habit and its socioeconomic aspects .in Jakarta

(lndonesian). Jakarra: FKMUI, I 981.

9.

Tanjung, Judin P. Effect on Smoking Deceased programamong

the

smoker-workersin

St.Carolus HospitalJakarta (Indonesian). Jakarta: FKMUI, 1995.

10.

Soetiarto, Farida. Relationship between habit on clovessmoking and dental destruction, among the drivers

of

ppD company in Jakarta (Indonesran). Jakarta,F

tJl j992.11.

HoepoedioRS. Action

on Smoking: Compilation of

pâpers on Cancer Problem (Indonesian). Jakarta: 1981.

Smoking problem in

Indonesia

65Syafranelsar. Proportion

of

Smoker amongthe

male employees in the office of Ditjen Binkesmas (Indonesian). Jakarta: FKUI, 1995.Shehbubakar, Sukaenah. Study

on

knowledge, attitudeand behaviour

on

smoking,among

the

pupils

of elementaryschool

gradesV

andVI

in

East Jakarta(Indonesian). Jakarta: Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia, 1992.

Indonesian Smoking Control Foundation. Meta-Analysis

Smoking

Pattern

in 14

Provinces

in

Indonesia(lndonesian). Jakarta: Indonesian

Smoking

Control Foundation("LM3"),

1998.National Household Health Survey 1980 (Indonesian).

Jakarta:

NIHRD Ministry

of

Health

Republic

ofIndonesia, 1980

World Health Organization. Geneva, Tobacco or Health:

A Global Status Report. World Health Organization, 1997.

National Household Health Survey 1980 (Indonesian).

Jakarta, NIHRD Ministry

of

Health

Republic

ofIndonesia, 1980

Aditama TY. Tobacco and Health (lndonesian). Jakarta,

UI Press I 997.

Kosen

S.

Analysis

of

Current Economic

Impact(Government and Community Perspective)

of

Smokingin

Indonesia. Jakarta:A

Report Submittedto

WHO Indonesia.NIHRD Ministry

of

Health

Republic of Indonesia,1998.Benyamin

M.

Smoking:An

East Java COpD Survey.Surabaya: Department

of

Pulmonology

AirlanggaUniversity School of Medicine, 1990.

Suryanto

E,

Yusuf A, HudoyoA.

Smoking and LungCancer (Indonesian).

MKI

1986: 36: 369-74.Tanuwijaya S. Youth Epidemiology Problems (Indonesian). National Congress of Pedi atrici an. Jakarta, I 999.

Demographic Foundation,

University

of

Indonesia.Reproductive Youth Health (Indonesian). Jakarta, I 992. Adisasmita A. Efïect of Passive Smoking on pregnancy

Outcome (Indonesian). Jakarta: FKMUI, 1993.

Wijayata

M.

Smoking Patrern Among Street VendorChildren

(Indonesian). Jakarta, Indonesian SmokingControl Foundation

("LM3"),

I995.'landra

YA.

Smoking Habit in High School, Denral andMedical School

(Indonesian).Jakarta,

IndonesianSmoking Control Foundarion

("LM3"),

1995.Shebubakar,

Jusuf A.

The Knowledge ancl

Attitude Concerning Cigarette Smoking Among Schoolchildren in Central Jakarta. Jâkarta: (lndonesian), Department of Respiratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia,1992I2

14

l3

l7

21. l5

l6

l8

t9

.A

22 23 14 25

26