Journal of Managerial Psychology

Emerald Article: Work-family conflict and individual consequences

Mian Zhang, Rodger W. Griffeth, David D. Fried

Article information:

To cite this document: Mian Zhang, Rodger W. Griffeth, David D. Fried, (2012),"Work-family conflict and individual consequences", Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 27 Iss: 7 pp. 696 - 713

Permanent link to this document:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02683941211259520

Downloaded on: 18-09-2012

References: This document contains references to 58 other documents To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY

For Authors:

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service. Information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

With over forty years' experience, Emerald Group Publishing is a leading independent publisher of global research with impact in business, society, public policy and education. In total, Emerald publishes over 275 journals and more than 130 book series, as

well as an extensive range of online products and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 3 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

Work-family conflict and

individual consequences

Mian Zhang

School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, and

Rodger W. Griffeth and David D. Fried

Department of Psychology, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA

Abstract

Purpose– The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between two forms of work-family conflict – work-family conflict and family-work conflict – and individual consequences for Chinese managers.

Design/methodology/approach– Participants of this study were 264 managers from Mainland China. The authors tested their hypotheses with structural equation modeling.

Findings– Work-family conflict was positively associated with emotional exhaustion. Family-work conflict was negatively associated with life satisfaction and affective commitment, as well as positively related to turnover intentions. Contrary to the research with samples of workers from Western countries (e.g. the USA), the study found that work-family conflict was positively associated with affective commitment and did not associate with turnover intentions for Chinese managers. Originality/value– Using the perspective of the Chinese prioritizing work for family benefits, the authors are the first to provide a preliminary test of the generalizability of the source attribution and the cross-domain models to Chinese managers. The paper’s findings provide the preliminary evidence that the cross-domain model works among the Chinese because of its cultural neutrality whereas the source attribution model cannot be used to predict the associations between work-family conflict and work-related consequences.

KeywordsWork-family conflict, Life satisfaction, Emotional exhaustion, Organizational commitment, Turnover intentions, Family life, Employees turnover, Job commitment

Paper typeResearch paper

Introduction

Work and family represent two important spheres in an adult’s social life. Work-family conflict is a form of inter-role conflict in which role demands originating from the work domain are incompatible with role demands stemming from the family domain (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). Work-family conflict is often viewed as a bidirectional construct: Work-family conflict may occur when work interferes with family (i.e. work-family conflict); it also may occur when family interferes with work (i.e. family-work conflict) (Netemeyeret al., 1996). This distinction is important because studies have shown that the two types of interference have different antecedents and consequences (Frone et al., 1992; Kelloway et al., 1999; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran, 2005; Netemeyer et al., 1996). Meta-analyses have revealed that high

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0268-3946.htm

work-family conflict and family-work conflict were related to a wide range of work-related consequences (e.g. low job satisfaction, reduced organizational commitment, high turnover intentions), family consequences (e.g. low marital and family satisfaction), and physical and psychological health problems (e.g. depression and poor physical health) (Allen et al., 2000; Ebyet al., 2005; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran, 2005).

Our literature review suggests two models that link bidirectional work-family conflict to individual consequences: the cross-domain model and the source attribution model. The cross-domain model proposes that interference from one role (e.g. work) makes it difficult for an individual to satisfy demands of the other role (e.g. family). Accordingly, the individual experiences greater distress in the role that receives the interference (Fordet al., 2007; Froneet al., 1992, 1997). The source attribution model suggests that an individual attributes the source of role conflict to the role that the individual believes caused the interference. Further, this model suggests that the individual will become dissatisfied with the role perceived to be the source of the conflict (Carret al., 2008; Shockley and Singla, 2011).

Current empirical support for these models is largely based on research that utilizes participants from countries with Western values (e.g. the US). Because the nature of work-family interface may vary along cultural boundaries (Luk and Shaffer, 2005; Ford

et al., 2007; Spectoret al., 2004, 2007), the extent to which predictions of the two models can be replicated among populations who espouse Eastern values, such as the Chinese, remains unclear.

To start to address this gap in literature, building on the perspectives from prior studies (e.g. Aryeeet al., 1999a, b; Yanget al., 2000), we argue that prioritizing work for family benefit is critical to understanding the nature of work-family interface among the Chinese. Specifically, when work interferes with family, a Chinese worker is less likely to attribute the source of interference to work because work is an important tool which is used to achieve overall benefit of family (Aryeeet al., 1999a, b). Besides, role senders from the Chinese family are likely to support the individual’s work priority behaviors because the behaviors are viewed as self-sacrifice made for the benefit of the family rather than a sacrifice of the family for the selfish pursuit of one’s own career development (Yanget al., 2000).

The central idea of this study is that how managers perceive work versus family roles is related to the associations between bidirectional work-family conflict and individual consequences. We propose that the cross-domain model is culturally neutral and, thus, works among Chinese samples. In contrast, we posit that a culture difference (i.e. prioritizing work for family benefits) may attenuate the effectiveness of the source attribution model among the Chinese, and, thus, some findings from Western cultures cannot be replicated in an Eastern one (i.e. China). To test our proposition, we explore the relationship between bidirectional work-family conflict and two health-related consequences (life satisfaction and emotional exhaustion) as well as two work-related consequences (affective commitment and turnover intentions) among Chinese managers.

This study contributes to work-family research by investigating a deeper layer that explainshowcultural differences are related to the associations between bidirectional work-family conflict (i.e. work-family conflict and family-work conflict) and individual consequences. Although prior studies have examined these associations among the

Work-family

conflict

Chinese (e.g. Aryeeet al., 1999a, b; Luet al., 2009; Spectoret al., 2007; Wanget al., 2004), to our knowledge, our study is the first to underscore the validity of the two models (i.e. the cross-domain model and the source attribution model) for predicting the associations. By weighing the two mechanisms simultaneously in China, we can potentially deepen our understanding of the associations between bidirectional work-family conflict and individual consequences, and provide a different perspective on how to manage work-family conflict among Chinese managers.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Work-family conflict

Work-family conflict research is largely based on role theory (Byron, 2005). According to Kahn and associates (Kahnet al., 1964), roles are the result of the anticipations of others about what is proper behavior in a particular position. Role demands arise from expectations articulated by work and family role senders (e.g. one’s employer, spouse, children) and/or from intrinsic values held by the individual regarding his or her own work and family role requirements (Kahn and Quinn, 1970; Katz and Kahn, 1978). Stress from role conflict occurs when individuals engage in multiple roles that are incompatible, and this role conflict is associated with psychological strain (Katz and Kahn, 1978). In line with role theory, we posit that the association between work-family conflict and individual consequences depends on expectations of both the self sender and other role senders.

As mentioned, work-family conflict and family-work conflict represent the bidirectional nature of this type of conflict. Work-family conflict occurs when work responsibilities hinder performance of family responsibilities (e.g. work obligations impede the ability to provide adequate child care). Family-work conflict arises when family activities hinder performance at work (e.g. marital problems impede job performance). Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) identified three types of work-family conflict: based, strain-based and behavior-based. In this study, we focus on time-and strain-based conflict because behavior-based conflict appears to have less predictive validity than the other two forms (Ling and Powell, 2001; Netemeyeret al., 1996).

Prioritizing work for family benefits: how the Chinese view work versus family roles

Some researchers imply that the Chinese value family less than Westerners do. These studies note that Western individualistic societies value family and personal time more than Eastern collectivist societies (Hofstede, 1980). For example, Shenkar and Ronen (1987) found that Mainland Chinese managers rated family and personal time as low in importance. Such findings seemingly contradict the view that people who reside in countries with collectivist values, such as China, place more importance on family than on work pursuits (e.g. Spectoret al., 2007; Yanget al., 2000).

However, the meanings of these self-report ratings should be interpreted within the larger social context in which the individuals are embedded (Carlson and Kacmar, 2000; Lobel, 1991). Some studies attribute Chinese emphasis on work to their collectivistic culture because collectivism encourages the Chinese to work for the welfare of the family (Spector et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2000). Therefore, Chinese tradition regards work as adding to family benefits, rather than competing with them (Redding, 1993). Specifically, the Chinese often view work activities as necessary for enhancing the financial welfare and social status of the family and believe the benefits

JMP

27,7

of an increased workload for the welfare of the family far exceed costs, such as lost personal time spent with family members (Yang et al., 2000). In contrast, Western workers may view work as an instrumental means to enhancing their own careers rather than as a way to provide for the welfare of the family (Yanget al., 2000).

Chinese work priority may also be viewed from an economic perspective (Aryee

et al., 1999a; Luet al., 2006). Luet al.(2006) contended that the Chinese were expected to put their jobs before their families because it was an indispensable means for maintaining and improving an acceptable living standard for their families. Aryeeet al.

(1999a) argued that the Chinese evaluated self-interest and economic gains at the family group level rather than at the individual level. To maximize economic benefits, Chinese families support and indeed require a strong commitment to the work role (Aryee et al., 1999a). Chinese people regard work as a way of fulfilling family responsibilities and emphasize work success because work is instrumental in obtaining the family’s economic well-being (Aryeeet al., 1999a).

We use the phrase “prioritizing work for family benefits” to summarize how the Chinese perceive work versus family roles. For most Chinese, the family is the root of life, and promoting the overall benefit of family is the ultimate goal that strengthens the root (Aryeeet al., 1999a; Yanget al., 2000). As such work is an important tool which is used to achieve overall benefit of the family. Therefore, when work interferes with family, an individual is less likely to attribute the source of the interference to the work role. Besides, role senders from the family side are likely to support the individual’s work priority behaviors.

Mechanisms linking work-family conflict to individual consequences

As noted previously, two major models link work-family conflict to individual consequences: the cross-domain model and the source attribution model. The cross-domain model suggests that individuals experience dissatisfaction with a role if they have difficulty meeting its demands because of hindrance stemming from another role (Ford et al., 2007; Frone et al., 1992, 1997). It follows that individuals should experience less affective attachment to the role for which they experience greater interference. Consistent with this prediction, empirical studies with Western participants reveal that individuals with high levels of work-family conflict experience greater family dissatisfaction than those with lower levels of work-family conflict. Further, individuals with high levels of family-work conflict experience greater job dissatisfaction than those with lower levels of family-work conflict (Ford

et al., 2007; Froneet al., 1992, 1997).

The core argument of the cross-domain model is that the interference caused by demands of one role often results in poor performance and low satisfaction with the other role. This cross-domain process does not depend on perceptions of the work-family relationship. For example, no matter if workers are American or Chinese, when they spend time taking care of sick children, they have to work faster or harder to meet a work goal. This may, in turn, relate to high levels of distress associated with the work role. Therefore, we posit that the model works in populations with different characteristics. In other words, the cross-domain model is universal, and, thus, the findings based on it can be replicated in other cultural settings such as China.

The source attribution model posits that individuals experience dissatisfaction with the role they perceive to be the cause of the interference (Carret al., 2008; Shockley and

Work-family

conflict

Singla, 2011). In short, this model posits that individual consequences are from the role domain that is attributed to be the source of work-family conflict. In line with this logic, some empirical findings show that work-family conflict associates with work-related consequences (Byron, 2005; Kossek and Ozeki, 1998), whereas family-work conflict relates to family-related consequences (Kossek and Ozeki, 1998). A recent meta-analysis found that the attribution formulation worked adequately with aggregated samples largely from Western countries (Shockley and Singla, 2011).

The central idea of the source attribution model assumes that a person would attribute the source of conflict to a role domain and, therefore, blame the role domain. Unlike the cross-domain model, the attribution formulation involves cognitive appraisal processes that occur with affective reactions (Shockley and Singla, 2011). However, the cognitive appraisal process may be related to sample characteristics. For example, when an individual sets work as the priority because of some reasons (e.g. high level of job involvement, being at the earlier career stage, heavy financial burden), the individual may not appraise the work role domain (i.e. the source of work interferes with family) negatively. Specifically, in our study, because the Chinese prioritize work for family benefits, when work interferes with family, the Chinese are less likely blame the work role. Therefore, the source attribution model is less likely to be effective in predicting the relationship between work-family conflict and work-related consequences among the Chinese.

Work-family conflict and health-related consequences

As a universal mechanism, the cross-domain model can furnish the theoretical basis that predicts the associations between bidirectional work-family conflict and health-related consequences among the Chinese. An individual likely experiences a high level of psychological distress associated with a given role if the individual frequently struggles to meet the role demands because hindrance stems from another role (Froneet al., 1992, 1997). Specifically, when work interferes with one’s family, the individual has difficulty in responding to family demands; conversely, when family interferes with work, the individual has difficulty meeting work demands. In either case, psychological distress can result. Further, psychological distress, no matter the origin, can worsen one’s health-related consequences (Froneet al., 1992).

Following this logic, we expect that the findings in Western samples can be replicated in our Chinese sample; that is, both work-family conflict and family-work conflict are associated with one’s greater overall feelings and attitudes about one’s life (e.g. life satisfaction; Dieneret al., 1985) and “psychological syndrome in response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job” (e.g. emotional exhaustion; Maslachet al., 2001, p. 397). Findings from Western societies have revealed that both work-family conflict and family-work conflict were associated with health-related consequences (Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran, 2005). Researchers found a negative relationship between bidirectional work-family conflict and life satisfaction (Kossek and Ozeki, 1998; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran, 2005). Empirical studies also found that work-family conflict was positively associated with burnout (Kossek and Ozeki, 1999).

The findings from Chinese samples largely uphold our propositions. Luet al.(2006) found that both work-family conflict and family-work conflict were negatively related to happiness for Taiwanese employees. Aryeeet al.(1999a) found work-family conflict

JMP

27,7

was negatively associated with life satisfaction, but they did not find a relationship between family-work conflict and life satisfaction. However, in a subsequent study, Aryeeet al.(1999b) found a negative relationship between family-work conflict and life satisfaction. Based on the foregoing, we posit that:

H1a. Work-family conflict is negatively related to life satisfaction.

H1b. Family-work conflict is negatively related to life satisfaction.

H2a. Work-family conflict is positively associated with emotional exhaustion.

H2b. Family-work conflict is positively associated with emotional exhaustion.

Work-family conflict and work-related consequences

The present study is concerned with the relationship between work-family conflict and two work-related consequences: affective commitment and turnover intentions. Affective commitment is defined as “the employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization” (Meyer and Allen, 1997, p. 11). A meta-analysis study has shown that both work-family conflict and family-work conflict were negatively associated with affective commitment (Allen et al., 2000). Meta-analyses also have shown that both work-family conflict and family-work conflict were positively related to turnover intentions (Kellowayet al., 1999; Kossek and Ozeki, 1999; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran, 2005).

Because of its cultural neutrality, the cross-domain model can be used to predict the associations that link family-work conflict to work-related consequences among the Chinese. When family interferes with work, an individual has difficulty in meeting the demands from the work domain, which leads to psychological strain associated with the work role. The psychological strain that may reduce one’s ability to adequately perform the work role will decrease the receipt of work-related rewards like promotions and salary (Aryee et al., 1999a), which in turn, may hurt one’s organizational attachment.

Empirical studies using Chinese samples uphold our logic. Studies found that family-work conflict was negatively related to job satisfaction (Aryeeet al., 1999a) and positively associated with turnover intentions (Wang et al., 2004). Therefore, using both theory and empirical findings, we derive the following hypotheses.

H3. Family-work conflict is negatively related to affective commitment.

H4. Family-work conflict is positively associated with turnover intentions.

The attribution model, however, may not work among Chinese samples. For most Chinese employees, work-family conflict is regarded as “normal” because putting work first is consistent with the high value they place on the work domain (Aryee et al., 1999a; Yanget al., 2000). Moreover, family members are likely to support one’s work priority behaviors (Aryeeet al., 1999a; Yanget al., 2000). The Chinese are less likely to blame the work domain when work interferes with family. Thus, we expect there may be null or weak associations between work-family conflict and affective commitment as well as turnover intentions.

Prior studies using Chinese samples largely support our anticipation. A number of studies found there was no association between work-family conflict and job

Work-family

conflict

satisfaction (Aryeeet al., 1999b), career satisfaction, affective commitment (Luet al., 2009) and turnover intentions (Wanget al., 2004; Yang, 2005). Only one study found a positive relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction (Luet al., 2006). A recent cross-cultural study revealed that two work-related outcomes ( job dissatisfaction and turnover intentions) were more positively associated with work-family conflict for Western individualist societies than for Eastern collectivist societies (Spectoret al., 2007).

Method

Sample and procedures

Study participants were managers (middle and top-level) from companies in China. We chose to study managers because they likely work long hours and have high levels of responsibility and demands at work (Spectoret al., 2007). Thus, we would anticipate that they experience conflict between work and family.

Questionnaires were distributed during six management training programs. All respondents were informed that their participation was totally voluntary. Following Podsakoffet al.’s (2003, p. 887) recommendation, we attempted to alleviate the problem of common source bias by asking respondents to answer different questionnaire measures at two time points, two hours apart. At time 1, respondents were given a questionnaire, which included an explanation of the purpose of the study, as well as a promise that any information used in the study would remain confidential. In addition, respondents provided demographic information and answered questions assessing work-family conflict and family-work conflict. Two hours later, respondents answered questions which assessed their life satisfaction, emotional exhaustion, affective commitment and turnover intentions.

Altogether, 358 surveys were distributed and 306 participants completed the questionnaires (i.e. a response rate of 85.4 percent). Following prior studies (e.g. Frone

et al., 1992; Frone et al., 1997), we excluded unmarried participants who had no

dependents at home from the analysis.

The final sample size was 264. The majority of respondents were male (81.5 percent) with an average age of 39 years (SD¼6). The vast majority of respondents had at least one child (87 percent). The average age of children was 13 (SD¼6). Participants worked an average of 51.8 hours per week (SD¼16.15). Consistent with previous research using Chinese samples (e.g. Luk and Shaffer, 2005), we found that the majority of participant spouses in this study were also employed (77.4 percent).

Measures

All the variables in our study were measured with well-established scales. Items in the scales were originally in English. We followed the process of back translation to ensure the quality of the measurements (Brislinet al., 1973). All measures used seven points Likert-type scales.

Work-family conflict

We assessed work-family conflict and family-work conflict with Frone and Yardley’s (1996) scale. The scale contains 12 items. Half of the items measure work-family conflict (A sample item is “My job or career keeps me from spending the amount of time I would like to spend with my family.”), and the other half assess family-work

JMP

27,7

conflict (A sample item is “My home life interferes with my responsibilities at work, such as getting to work on time, accomplishing daily tasks, or working overtime.”). The Cronbach alpha estimate for work-family conflict was 0.83, and that for family-work conflict was 0.84.

Life satisfaction

We assessed life satisfaction with five items from Diener et al.’s (1985) scale. One sample item is “In most ways, my life is close to ideal.” The Cronbach alpha estimate was 0.84.

Emotional exhaustion

We evaluated emotional exhaustion with five items from Schaufeliet al.(1996). An example item is “I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job.” The Cronbach alpha estimate was 0.89.

Affective commitment

We measured affective commitment with five items from Meyer and Allen’s (1997) scale. One sample item is “I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own.” The Cronbach alpha estimate was 0.88.

Turnover intentions

We assessed turnover intentions with three items from Wayneet al.’s (1997) study. An example item is “I am seriously thinking about quitting my job.” The Cronbach alpha estimate was 0.85.

Control variables

We measured age, gender, the existence of children, average age of children and spousal work status as control variables. Age was measured as a continuous variable. Gender, the existence of children and spousal work status were dichotomized as dummy variables.

Data analyses

The analysis consisted of a two-step process (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). First, construct validity of our measurement model was assessed with confirmatory factor analysis. Second, our hypotheses were tested with structural equation modeling (SEM). We analyzed the covariance matrix using the maximum likelihood procedure in LISREL 8.50 ( Jo¨reskog and So¨rbom, 2001). We did not include control variables when testing hypotheses because they did not exhibit zero-order correlations with criteria (see Table I).

Following recommendations by Bollen and Long (1993) as well as Hu and Bentler (1998, 1999), we used multiple fit indices, including thex2/df, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Incremental Fit Index (IFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). CFI and IFI surpassing 0.90 indicate good fit, and values equal to or exceeding 0.95 signal excellent fit (Hu and Bentler, 1998). The RMSEA and the SRMR less than or equal to 0.05 signal close fit; 0.05-0.08 values indicate reasonable fit (Browne and Cudeck, 1992; Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Work-family

conflict

Variables Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Gender 0.82 0.39

Age 12.89 6.62 20.00

The existence of children 0.87 0.33 20.03 0.36* * * Average age of children 12.75 6.48 20.01 0.88* * * 0.01

Spouse work status 0.87 0.34 20.19* * 20.01 0.03 0.04

Work-family conflict 5.32 1.25 0.05 20.17* * * 0.12 20.26* * * 20.15* (0.83)

Family-work conflict 2.03 0.84 0.07 0.10 20.10 0.04 20.01 20.09 (0.84)

Life satisfaction 4.46 1.05 20.02 0.06 0.11 0.01 0.10 20.12 20.12* (0.84)

Emotional exhaustion 4.01 1.32 20.05 0.05 20.04 20.02 0.08 0.30* * * 0.15* 20.22* * * (0.89)

Affective commitment 5.46 1.06 0.01 20.10 0.09 20.04 20.06 0.12 20.21* * 0.20* * 20.16* * (0.88)

Turnover intentions 2.60 1.30 20.04 0.06 20.05 20.01 0.09 20.04 0.25* * * 20.01 0.15* 20.49* * * (0.85)

Notes: *p,0.05;* *p, 0.01;* * *p, 0.001; two-tailed test. The number in parenthesis on the diagonal of the table is Cronbach’s alpha estimate

Table

I.

The

descriptive

statistics

and

zero-order

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

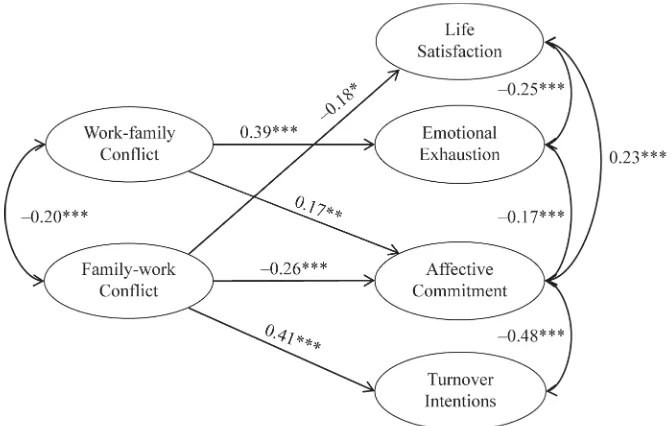

An overall measurement model for all the variables in Figure 1 was assessed. We conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses. Using modification indices, we deleted twelve items of the variables because of the potential problem of cross loading. However, each construct had at least three measurement items after the deletion. The final factor model fit the data, and fit indices achieved acceptable levels (x2/df¼2.71; RMSEA¼0.08; CFI¼0.94; IFI¼0.94; SRMR¼0.06). Besides, all factor loadings were statistically significant. The results showed that the variables in our measurement model had appropriate convergent and discriminant validity.

Assessing common source bias

The problem of common source bias may exist because all predictors and dependent variables were self-reported (Podsakoffet al., 2003). To assess the potential nature of this problem, we took two approaches recommended by Podsakoffet al.’s (2003). First, we conducted a Harmon one-factor test. The single-factor measurement model poorly fit the data (x2/df¼24.05; RMSEA¼0.30; CFI¼0.34; IFI¼0.35; SRMR¼0.25), suggesting that same source bias might not a serious problem. Second, we added an artificial common source construct into the final measurement model with all items loading on it. The fit indices fell into acceptable level but did not achieve substantial improvement (x2/df¼2.80; RMSEA¼0.08; CFI¼0.95; IFI¼0.95; SRMR¼0.05). Although the chi-square decrease was statistically, significantly different (Dx2¼37

:35;Ddf ¼18;p,0:05), the variance extracted by the common source factor was 0.25, falling below the 0.50 cutoff that has been suggested as indicating the

Figure 1. Maximum likelihood parameter estimates for the paths in SEM model

Work-family

conflict

existence of a latent factor representing the manifest indicators (Dulacet al., 2008). All of the previous results indicated that common source bias was not a serious problem in the current study.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations

Table I shows the descriptive information and zero-order correlations among variables in the current study. The simple correlations in Table I provide preliminary support for

H1b,H2a,H2b,H3,H4. Work-family conflict was positively associated with emotional exhaustion (r¼0:30;p,0:001). Family-work conflict was negatively related to life satisfaction (r¼20:12;p,0:05) and positively associated with emotional exhaustion (r¼0:15;p,0:05). Family-work conflict was negatively related to affective commitment (r¼20:21;p,0:001) and positively associated with turnover intentions (r¼0:25;p,0:001). However, work-family conflict did not show a relationship with life satisfaction.

Testing hypotheses

Figure 1 shows the standardized path estimates of the SEM. This model achieved an acceptable level of fit (x2/df¼2.71; RMSEA¼0.08; CFI¼0.94; IFI¼0.94; SRMR¼0.06).When outcomes were psychological health variables, family-work conflict was negatively associated with life satisfaction (g¼20:18;p,0:05). Thus, H1b was supported. Work-family conflict was positively related to emotional exhaustion (g¼0:39;p,0:001). Therefore, the finding upheld H2a. However, work-family conflict was not related to life satisfaction, and family-work conflict was not associated with emotional exhaustion. Thus, ourH1aandH2bwere not supported. With regard to work-related outcomes,H3andH4 were supported: family-work conflict was negatively associated with affective commitment (g¼20:26;p,0:001) and positively related to turnover intentions (g¼0:41;p,0:001).

We also sought to test whether relationships occurred between work-family conflict and affective commitment and between work-family conflict and turnover intentions. Results did not show evidence of a relationship between work-family conflict and turnover intentions. Interestingly, work-family conflict was positively associated with affective commitment (g¼0:17;p,0:01).

Discussion

Theoretical implications

We contribute to work-family research by investigating the idea that cultural differences are related to the associations between bidirectional work-family conflict and individual consequences. Although prior studies have examined the associations among the Chinese (e.g. Aryeeet al., 1999a, b; Spectoret al., 2007; Wanget al., 2004), to our knowledge, our study makes specific contributions by examining how Chinese prioritization of work for family benefits is associated with the extent to which the two models (i.e. the cross-domain model and the source attribution model) work in Chinese cultural settings. We propose that the cross-domain model also works among the Chinese because of its cultural neutrality, whereas the source attribution model cannot be used to predict the associations between work-family conflict and work-related consequences because the Chinese are less likely to blame the source of work-family conflict (i.e. work domain).

JMP

27,7

The findings largely support our hypotheses. With regard to health-related consequences, consistent with our expectation, Chinese managers who perceived greater family-work conflict reported lower satisfaction with their lives. However, we did not find support for our prediction that Chinese managers who experience greater work-family conflict would report lower life satisfaction. The null association may be because social support from family members buffers the negative association. As we expected, work-family conflict was positively associated with emotional exhaustion. However, we did not find a positive association between family-work conflict and emotional exhaustion. The null association may be because emotional exhaustion largely stems from excessive job demands rather than family demands.

As for work-related consequences, consistent with the cross-domain model (Frone

et al., 1992, 1997) and the findings from Western studies (Allenet al., 2000; Kossek and Ozeki, 1999), we found that Chinese managers who perceived higher levels of family-work conflict were less committed to their organizations and had stronger intentions to quit. Contrary to the source attribution model (Shockley and Singla, 2011) and empirical research in Western countries (Allen et al., 2000; Kossek and Ozeki, 1999), we did not find evidence for a negative relationship between work-family conflict and two work-related consequences (i.e. affective commitment and turnover intentions). Frone (2003) argued that work-family conflict was more critical because work-family conflict was greater than family-work conflict and was more associated with work-related consequences. A recent meta-analysis found that the source attribution model was the more influential mechanism that links bidirectional work-family conflict and individual consequences (Shockley and Singla, 2011). In a cross-cultural study, Spector and associates accepted Frone’s (2003) argument and did not explore the relationship between family-work conflict and work-related consequences (Spector et al., 2007). We conducted a t-test and found work-family conflict was also greater than family-work conflict [tð305Þ ¼32:66;p,0:001]. However, our findings suggest that future studies using Chinese samples should include family-work conflict because of the relationship between family-work conflict and individual consequences.

There are two interesting findings that need additional discussion. First, we found that work-family conflict was negatively correlated to family-work conflict (F¼20:20;p,0:01). This finding is not consistent with extant findings. Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran (2005) conducted a meta-analysis of 25 studies with US samples and found that the correlations range from 0.16 to 0.59. Consistent with the perspective of work priority for family benefits, our finding suggests that the Chinese may perceive work and family roles in a complementary, rather than competing, way. Second, work-family conflict was positively associated with affective commitment (g¼0:17;p,0:01). This finding suggests the Chinese who experience work-family conflict could develop positive attitudes toward their employers because work demands can ultimately bring benefits to them and to their families.

Implications for management practice and society

Our findings have practical implications for how to manage work-family conflict among Chinese workers. The associations between family-work conflict and individual consequences suggest managers should adopt some measures to decrease family-work conflict. Family friendly practices (e.g. flexible time schedule, telecommuting and

Work-family

conflict

family support culture) may reduce family-work conflict because these practices could facilitate employees’ responding to family demands.

Someone may conclude work-family conflict is not a significant issue in managing Chinese employees because there are no associations between work-family conflict and work-related consequences. We challenge this conclusion because of two following reasons. First, although work-family conflict did not show correlations with work-related consequences, it was positively related to emotional exhaustion, which may further relate to physical and psychological health problems (Maslachet al., 2001). Second, we suggest that managers should pay attention to the underlying reasons. Although our findings do suggest Chinese managers are likely to endure more work-family conflict than their Western counterparts, this outcome may be for long-term returns for their families. Our findings suggest managers may help Chinese employees conduct career planning and achieve career goals which are likely to compensate for their enduring work-family conflict.

With the fast pace of modernization in China, work-family conflict has been becoming a societal issue (Luet al., 2009; Siuet al., 2005). Because Chinese workers may prioritize work behaviors, they may also suffer from health-related problems such as emotional exhaustion and life dissatisfaction. Researchers note that work overload and work-family conflict are two significant factors that may worsen a person’s happiness in the current Chinese society (Lu, 2006). A recent study finds that, though per capita GDP in China is 2.8 times higher in 2000 than in 1990, the percentage of Chinese describing themselves as very happy declined from 28 percent to 12 percent, and the average life satisfaction rating fell from 7.3 to 6.5 (on the ten-point scale) (Brockman

et al., 2009). To reduce the potential decline of health-related consequences such as life satisfaction, the society needs to promote the meaning of balancing work and family roles and emphasize the important of personal interests.

Limitations and future directions

The most serious limitation of this paper is the lack of a causal relationship between work-family conflict and work-related variables. Because most extant studies use work-family conflict as a predictor, we assume the direction is from work-family conflict to work-related variables. However, another explanation is possible: Less satisfaction or commitment may result in high family-work conflict because employees who are dissatisfied with their jobs and their organizations may put more effort on responding to family demands (Wiley, 1987). If a Chinese worker gives priority to family demands, this may imply that the worker has lost his or her loyalty to the organization. In the future, there is a need to design research from which the assessment of causality can be inferred.

One may question why we did not measure the Chinese prioritization of work for family benefits with scales such as job involvement, family involvement or work-family centrality. The reason is that extant scales cannot accurately assess the meaning of the Chinese prioritizing work for family benefits. For example, one sample item from Carret al.’ (2008) work-family centrality scale was “The major satisfaction in my life comes from my work rather than my family.” However, for the Chinese, emphasizing work may not mean the major satisfaction in their life comes from their work. Because the Chinese tend to view work as an important tool which is used to achieve an overall benefit to the family (Aryeeet al., 1999a; Yanget al., 2000), a Chinese

JMP

27,7

respondent probably gives a low score to the sample measurement item, but is highly committed to work priority behaviors. Future studies may measure prioritization of work for family benefits by developing appropriate scenario questions.

Future studies can also explore the relationship between bidirectional work-family conflict and other outcomes among Chinese workers. For example, we anticipate that work-family conflict would be associated with better individual performance ratings. Possible reasons are twofold. First, Chinese workers who experience greater levels of work-family conflict probably put more time and effort into their work, which should make it easier to achieve good performance outcomes. Second, putting more time and effort should give the supervisor a good impression because setting work as a priority is consistent with the Chinese work ethic norm. Therefore, supervisors would be inclined to give good performance evaluations to subordinates who have greater levels of work-family conflict. Future studies can verify such propositions.

We are cautious about the generalization of our findings among Chinese employees because they are based on a view that the Chinese prioritize work for family benefits. With the process of modernization in China, work value diversity has been increasing (Siuet al., 2005). We speculate that the findings in this study may not be generalized to Chinese workers who do not hold the viewpoint of prioritization of work for family benefits. There is evidence that the younger generations in China have a different work ethic. Compared with the Chinese born in the 1970s, those born in the 1980s are reported to pay more attention to leisure and non-career interests (Zhu and Chen, 2006). Further studies can investigate whether there are different patterns of work-family priority among various age groups of Chinese workers.

It could be argued that there are other reasons associated with the high value of work priority among Chinese workers. For example, because China is a developing country, economic insecurity may force people to work hard in order to save money for the future, or to avoid being laid off. Workforce demand is lower than the supply of workers, and this creates a competition among workers to get and keep jobs. Chinese workers have to put work first. There is a one-child policy in China’s mainland, and this reduces family demands. These factors could increase the Chinese worker’s relatively high priority for work. However, we believe that culture is the underlying reason because the emphasis on work is also found among workers in other Eastern countries. Korea and Japan are good examples. Both countries have implemented capitalism, and they do not have a one-child policy. However, similar to the Chinese, the majority of employees in Korea and Japan give high priority to work (Kanai and Wakabayashi, 2001, 2004). Hence, we contend that cultural factors found in Eastern cultures may be critical to molding the Chinese prioritization of work for family benefits. Additional research can be designed to control for possible reasons from other sources such as economic insecurity, a one-child policy, and family structure.

References

Allen, T.D., Herst, D.E.L., Bruck, C.S. and Sutton, M. (2000), “Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research”,Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 278-308.

Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W. (1988), “Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach”,Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103 No. 3, pp. 411-23.

Work-family

conflict

Aryee, S., Fields, D. and Luk, V. (1999a), “A cross-cultural test of a model of the work-family interface”,Journal of Management, Vol. 25 No. 4, pp. 491-511.

Aryee, S., Luk, V., Leung, A. and Lo, S. (1999b), “Role stressors, interrole conflict, and well-being: the moderating influence of spousal support and coping behaviors among employed parents in Hong Kong”,Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 54 No. 2, pp. 259-78. Bollen, K.A. and Long, J.S. (1993),Testing Structural Equation Models, Sage, Newbury Park, CA. Brislin, R., Lonner, W.J. and Thorndike, R.M. (1973),Cross-cultural Research Methods, Wiley,

New York, NY.

Brockman, H., Delhey, J., Weizel, C. and Yuan, H. (2009), “The China puzzle: falling happiness in a rising economy”,Journal of Happiness Studies, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 387-405.

Browne, M.W. and Cudeck, R. (1992), “Alternative ways of assessing model fit”,Sociological Methods and Research, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 230-58.

Byron, K. (2005), “A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents”,Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 67 No. 2, pp. 169-98.

Carlson, D.S. and Kacmar, K.M. (2000), “Work-family conflict in the organisation: do life role values make a difference”,Journal of Management, Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 1031-54.

Carr, J.C., Boyar, S.L. and Gregory, B.T. (2008), “The moderating effect of work-family centrality on work-family conflict, organizational attitudes, and turnover behavior”, Journal of Management, Vol. 34 No. 2, pp. 244-62.

Diener, E., Emmons, R.A., Larsen, R.J. and Griffin, S. (1985), “The satisfaction with life scale”,

Journal of Personality Assessment, Vol. 49 No. 1, pp. 71-5.

Dulac, T., Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.M., Henderson, D.J. and Wayne, S.J. (2008), “Not all responses to breach are the same: the interconnection of social exchange and psychological contract processes in organizations”,Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 51 No. 6, pp. 1079-98. Eby, L.T., Casper, W.J., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux, C. and Brinley, A. (2005), “Work and family research in IO/OB: content analysis and review of the literature (1980-2002)”,Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 66 No. 1, pp. 124-97.

Ford, M., Heinen, B. and Langkamer, K. (2007), “Work and family satisfaction and conflict: a meta-analysis of cross-domain relations”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 92 No. 1, pp. 57-80.

Frone, M.R. (2003), “Work-family balance”, in Quick, J.C. and Tetrick, L.E. (Eds),Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 143-62.

Frone, M.R. and Yardley, J.K. (1996), “Workplace family-supportive programmes: predictors of employed parents’ importance ratings”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 69 No. 4, pp. 351-66.

Frone, M.R., Russell, M. and Cooper, M.L. (1992), “Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: testing a model of the work-family interface”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 77 No. 1, pp. 65-78.

Frone, M.R., Yardley, J.K. and Markel, K.S. (1997), “Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family interface”,Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 145-67. Greenhaus, J.H. and Beutell, N.J. (1985), “Source of conflict between work and family roles”,

Academy of Management Review, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 76-88.

Hofstede, G. (1980),Culture’s Consequence: International Differences in Work-related Values, Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

JMP

27,7

Hu, L.T. and Bentler, P.M. (1998), “Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification”, Psychological Methods, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 424-53.

Hu, L.T. and Bentler, P.M. (1999), “Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives”,Structural Equation Modeling, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 1-55.

Jo¨reskog, K.G. and So¨rbom, D. (2001),LISREL 8.51, Scientific Software, Chicago, IL.

Kahn, R.L. and Quinn, R.P. (1970), “Role stress: a framework for analysis”, in McLean, A. (Ed.),

Occupational Mental Health, Rand-McNally, New York, NY, pp. 50-115.

Kahn, R.L., Wolfe, D.M., Quinn, R., Snoek, J.D. and Rosenthal, R.A. (1964),Organizational Stress, Wiley, New York, NY.

Kanai, A. and Wakabayashi, M. (2001), “Workaholism among Japanese blue-collar employees”,

International Journal of Stress Management, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 129-45.

Kanai, A. and Wakabayashi, M. (2004), “Effects of economic environmental changes on job demands and workaholism in Japan”,Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 17 No. 5, pp. 537-48.

Katz, D. and Kahn, R.L. (1978),The Social Psychology of Organizations, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Kelloway, E.K., Gottlieb, B.H. and Barham, L. (1999), “The source, nature, and direction of work and family conflict: a longitudinal investigation”, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 337-46.

Kossek, E.E. and Ozeki, C. (1998), “Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: a review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 83 No. 2, pp. 139-49.

Kossek, E.E. and Ozeki, C. (1999), “Bridging the work-family policy and productivity gap: a literature review”,Community, Work and Family, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 7-33.

Ling, Y. and Powell, G. (2001), “Work-family conflict in contemporary China: beyond an American-based model”,International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, Vol. 1 No. 3, pp. 357-73.

Lobel, S.A. (1991), “Allocation of investment in work and family roles: alternative theories and implications for research”,Academy of Management Review, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 507-21. Lu, C.Q. (2006), “The flu of the twenty-first century: killers of happiness”,People Forum, Vol. 15

No. 6, pp. 12-18 (in Chinese).

Lu, L., Gilmour, R., Kao, S.F. and Huang, M.T. (2006), “A cross-cultural study of work/family demands, work/family conflict and wellbeing: the Taiwanese vs British”, Career Development International, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 9-27.

Lu, J.F., Siu, O.L., Spector, P.E. and Shi, K. (2009), “Antecedents and outcomes of a fourfold taxonomy of work-family balance in Chinese employed parents”,Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 182-92.

Luk, D.M. and Shaffer, M.A. (2005), “Work and family domain stressors and support: direct and indirect influences on work-family conflict”,Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 78, December, pp. 489-508.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W.B. and Leiter, M.P. (2001), “Job burnout”,Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 52 No. 1, pp. 397-422.

Mesmer-Magnus, J.R. and Viswesvaran, C. (2005), “Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: a meta-analytic examination”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 67 No. 2, pp. 215-32.

Work-family

conflict

Meyer, J.P. and Allen, N.J. (1997), Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Application, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Netemeyer, R.G., Boles, J.S. and McMurrian, R. (1996), “Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 81 No. 4, pp. 400-10.

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y. and Podsakoff, N.P. (2003), “Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies”,

Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88 No. 5, pp. 879-903.

Redding, S.G. (1993),The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism, Walter de Gruyter, New York, NY. Schaufeli, W.B., Leiter, M.P., Maslach, C. and Jackson, S.E. (1996), “Maslach burnout

inventory-general survey”, in Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E. and Leiter, M.P. (Eds),The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Test Manual, 3rd ed., Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA.

Shenkar, O. and Ronen, S. (1987), “Structure and importance of work goals among managers in the People’s Republic of China”,Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 30 No. 3, pp. 564-7.

Shockley, K.M. and Singla, N. (2011), “Reconsidering work-family interactions and satisfaction: a meta-analysis”,Journal of Management, Vol. 37 No. 3, pp. 861-86.

Siu, O.L., Spector, P.E., Cooper, C.L. and Lu, C.Q. (2005), “Work stress, self-efficacy, Chinese work values and work well-being in Hong Kong and Beijing”,International Journal of Stress Management, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 274-88.

Spector, P.E., Cooper, C.L., Poelmans, S., Allen, T.D., O’Driscoll, M., Sanchez, J.I., Siu, O.L., Dewe, P., Hart, P. and Lu, L. (2004), “A cross-national comparative study of work/family stressors, working hours, and well-being: China and Latin America vs the Anglo world”,Personnel Psychology, Vol. 57 No. 1, pp. 119-42.

Spector, P.E., Allen, T.D., Poelmans, S., Lapierre, L.M., Cooper, C.L., Sanchez, J.I., Abarca, N., Alexandrova, M., Beham, B. and Brough, P. (2007), “Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfaction and turnover intentions with work-family conflict”,Personnel Psychology, Vol. 60 No. 4, pp. 805-35.

Wang, P., Lawler, J.J., Walumbwa, F.O. and Kan, S. (2004), “Work-family conflict and job withdrawal intentions: the moderating effect of cultural differences”,International Journal of Stress Management, Vol. 11 No. 4, pp. 392-414.

Wayne, S.J., Shore, L.M. and Liden, R.C. (1997), “Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: a social exchange perspective”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40 No. 1, pp. 82-111.

Wiley, D.L. (1987), “The relationship between work/nonwork role conflict and job-related outcomes: some unanticipated findings”,Journal of Management, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 467-72. Yang, N.N. (2005), “Individualism-collectivism and work-family interfaces: a Sino-US comparison”, in Poelmans, S.A. (Ed.), Work and Family: An International Research Perspective, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 287-318.

Yang, N.N., Chen, C.C., Choi, J. and Zou, Y.M. (2000), “Sources of work-family conflict: a Sino-US comparison of the effects of work and family demands”,Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 43 No. 1, pp. 113-23.

Zhu, Q.S. and Chen, W.Z. (2006), “A survey of the concept of value among Chinese employees and managers in the economic transformation”,Journal of Sichuan University, Vol. 1, pp. 19-23 (in Chinese).

JMP

27,7

Further reading

Cooke, R.A. and Rousseau, D.M. (1984), “Stress and strain from family roles and work role expectations”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 69 No. 2, pp. 252-60.

Klein, K.J. and Kozlowski, S.W.J. (2000), “From micro to meso: critical steps in conceptualizing and conducting multilevel research”, Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 211-36.

About the authors

Mian Zhang is Associate Professor at the School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University. His primary research interests include organizational attachment, motivation, work-family conflict and social capital. He has published articles in journals such asHuman Relations, Human Resource Management Review, Human Resource Development Quarterly,

Frontiers of Business Research in China, and others. He is currently on the editorial board of

Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management. Mian Zhang is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: zhangm6@sem.tsinghua.edu.cn

Rodger W. Griffeth received his PhD from the University of South Carolina. He is the Byham Chair of Industrial and Organizational Psychology and Professor of Psychology at Ohio University. Formerly he held the Freeport-McMoRan Chair of Human Resource Management, University Research Professor, and Professor of Management at the University of New Orleans. Prior to his present position, Dr Griffeth was a tenured faculty member at Georgia State University, George Mason University, Louisiana State University and Kent State University. His primary research interest is investigating employee turnover processes, and in 1995 he co-authored a research book with Peter Hom entitled Employee Turnover, published by Southwestern Publishing Company. In 2001, he wrote and published Retaining Valued Employees for Sage Publishers. Dr Griffeth is Editor ofHuman Resource Management Review

for Elsevier Press.

David D. Fried obtained his Master of Science degree in Industrial and Organizational Psychology at Ohio University. He is currently a consultant at SWA Consulting Inc. in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Work-family

conflict

713

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail:reprints@emeraldinsight.com