SILVICULTURAL

PRACTICES

AND

GROWTH

OF

JABON

TREE

(

Anthocephalus

cadamba

Miq)

IN

COMMUNITY

FOREST,

WEST

JAVA,

INDONESIA

JINWON

SEO

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY BOGOR

DECLARATION

OF

ORIGINALITY

I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “Silvicultural Practices and Growth of Jabon Tree (Anthocephalus cadamba Miq) in Community Forest, West Java, Indonesia” and the work reported herein was composed by and originated entirely from me. I declare that this is a true copy of my thesis, as approved by my supervisory committee and has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other University or Institution. Information derived from the published and unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and references are given in the list of sources.

I hereby assign the copyright of my writings to the Bogor Agricultural University.

Bogor, January 2013

SUMMARY

JINWON SEO. Silvicultural Practices and Growth of Jabon Tree (Anthocephalus cadamba Miq) in Community Forest, West Java, Indonesia. Supervised by IRDIKA MANSUR, SRI WILARSO BUDI and TATANG TIRYANA

Jabon (Anthocephalus cadamba Miq.) is a native species in Indonesia. This fast growing tree is now preferred for the local community to plant because of its good adaptability and economic profitability. However, the information of this tree and silvicultural practices is still lacking. Therefore, there are three main objectives of this research: 1) to document the existing silvicultural practices of jabon implemented by local communities in West Java. 2) to investigate tree growth performance among different sites in West Java. 3) to examine the linkage of silvicultural practices and soil fertility for stand quality.

This research covered following aspects; stand inventory, soil sampling and interview with local communities who planted jabon in the districts of Bogor, Sukabumi, Sumedang and Purwakarta. With 0.02 or 0.04 ha size sample plots, a stand inventory has been conducted and the diameter and height are measured. In addition, pest investigation also has been carried out at same sample plots. In addition, soil sampling and interview have done to collect site information and silvicultural practices in each site. After collecting various data from jabon plantation in West Java, those data are analyzed in forms of tabulation and regression graph.

According to the results of the interview, most jabon plantations are owned by outsiders from Jakarta or other cities. There are three types of management: partnership, hiring employees and direct management. There are only a few practitioners have participated in silvicultural training. In spite of the absence of systematic silvicultural training, all practitioners have implemented basic silvicultural practices: land preparation and planting, fertilizing, maintenance and pest and disease control. Moreover, most of sites in same village have same or similar silvicultural practices because usually only one manager or farmer maintains all plantations.

After an inventory of jabon plantations in West Java, there are totally 56 plots have been inventoried in 20 sites. The age of jabon tree ranges from 0.5-year to 3.5-year because jabon tree has been introduced in Java since 2008. The mean diameter ranges from 2.45 cm to 14.57 cm with maximum 29.3 cm and the mean height of 1.29 m to 12.62 m with maximum 18.68m in Situgede. As a result of regression modeling with dominant height, one Chapman model has been selected to calculate site index curve.: Hd . exp . t . with 0.6513 R-square value. This curve helps to divide 20 sites into three categories: good, medium and poor. Based on analysis, there are two good sites, twelve medium and six poor sites. There are three DBH-age equations can be estimated based on site classifications. As a result of comparison between good and poor sites, it seems that site conditions and soil fertility have a more significant impact on growth of jabon than silvicultrual practices like fertilization and maintenance.

RINGKASAN

JINWON SEO, Praktek silvikultur dan Pertumbuhan Pohon Jabon

(Anthocephalus cadamba Miq.) pada Hutan Kemasyarakatan, Jawa barat,

Indonesia. Dibawah bimbingan IRDIKA MANSUR, SRI WILARSO BUDI dan TATANG TIRYANA

Jabon (Anthocephalus cadamba Miq.) merupakan jenis pohon cepat tumbuh asli Indonesia yang disukai oleh masyarakat karena adaptabilitas dan nilai ekonomi tinggi. Informasi mengenai pohon dan praktek silvikultur masih terbatas, Oleh karena itu, tujuan dari penelitian ini adalah: 1) mengumpulkan informasi mengenai praktek silvikultur yang telah dilaksanakan oleh masyarakat lokal di Jawa Barat 2) menginvestigasi performa pertumbuhan pada lokasi penanaman yang berbeda di Jawa Barat 3) menguji hubungan praktek silvikultur dengan kesuburan tanah untuk mengetahui kualitas tegakan.

Aspek yang diteliti meliputi inventarisasi tegakan, pengujian contoh tanah, dan wawancara dengan masyarakat penanam jabon di wilayah Bogor, Sukabumi, Sumedang dan Purwakarta. Sebanyak 56 plot contoh dengan ukuran 0.02 atau 0.04 ha dibuat di 20 lokasi untuk melakukan pengukuran tinggi dan diameter pohon, dan serangan hama. Selain tinggi dan diameter, pada plot contoh juga diamati kerusakan pohon akibat hama. Data yang diperoleh dari lapangan, kemudian dianalisis dan disajikan dalam bentuk tabulasi dan grafik regresi.

Berdasarkan dari hasil wawancara, sebagaian besar pemilik modal penanaman jabon berasal dari luar kota. Terdapat tiga tipe dari sistem menejemen yang dilakukan yaitu: kerjasama, menggaji karyawan, dan melakukan menejemen langsung yang dilakukan oleh pemilik modal. Berdasarkan informasi yang diperoleh, diketahui masih sedikit pengelola yang telah mengikuti pelatihan teknik selvikultur jabon Namun demikian semua pengelola telah menerapkan teknik dasar silvikultur seperti persiapan lahan, penanaman, pemupukan, serta pengendalian gulma, hama dan penyakit.

Dari hasil inventarisasi diketahui pohon jabon di lapangan berusia antara 0,5 sampai 3.5 tahun, karena pohon jabon baru diperkenalkan sejak tahun 2008. Interval diameter rata-rata berkisar 2.45 cm sampai 14.57 cm, dengan nilai terbesar 29.3 cm dan tinggi rata-rata berkisar antara 1.29 m sampai dengan 12.62 m dengan tinggi maksimal sebesar 18.68 m di lokasi Situgede Bogor. Model Chapman digunakan untuk menghitung kurva index tempat tumbuh. Berdasarkan model regresi dari peninggi tegakan, nilai kurva index tempat tumbuh: Hd

. exp . t . dengan nilai R-Square 0.6513. Nilai dari

kurva ini, membagi 20 lokasi menjadi 3 katagori yaitu baik (2), sedang (12), dan buruk (6). Terdapat tiga persamaan antara umur dan diameter (DBH), yang dapat diperkirakan berdasarkan klasifikasi dari lokasi. Hasil dari perbandingan antara lokasi baik dan buruk, tampak bahwa kondisi lokasi dan kesuburan tanah lebih memberikan pengaruh yang nyata terhadap pertumbuhan jabon, dibanding dengan praktek silvikultur seperti pemupukan dan pemeliharaan.

© Copyright owned by IPB, 2013

All rights reserved

SILVICULTURAL

PRACTICES

AND

GROWTH

OF

JABON

TREE

(

Anthocephalus

cadamba

Miq)

IN

COMMUNITY

FOREST,

WEST

JAVA,

INDONESIA

JINWON

SEO

Thesis

As the requirement for the degree of Master of Science

In

Tropical Silviculture

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY BOGOR

Thesis Title : Silvicultrual Practices and Growth of Jabon Tree (Anthocephalus cadamba Miq) in Community Forest, West Java, Indonesia Name : Jinwon Seo

Student ID : E451108021

Approved by,

Dr. Ir. Irdika Mansur, M. For. Sc. Main-Supervisor

Dr. Ir. Sri Wilarso Budi R., M.S. Dr. Tatang Tiryana, S.Hut., M.Sc.

Co-Supervisor Co-Supervisor

Endorsed by

Head of Major Dean of Graduate School

Tropical Silviculture

Dr. Ir. Basuki Wasis, M.S. Dr. Ir. Dahrul Syah, M.Sc. Agr.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

First of all, I would like to give my sincere appreciation and gratitude to Dr. Irdika Mansur, Dr. Sri Wilarso Budi and Dr. Tatang Tiryana, who gave me a valuable supervision, guidance, enthusiasm and especially great patience for the completion of this thesis. Without my honorable advisor’s advice and help, I could not finish my thesis with satisfaction.

I wish to acknowledge SEAMEO BIOTROP (Southeast Asian Regional Centre for Tropical Biology) for giving a chance to participate in a research project. Without supports from BIOTROP, this thesis cannot be implemented successfully because of its expenses for research. I want to express also special thanks for great helps from the staffs at subdistrict offices and village offices located in Bogor, Purwakarta, Sukabumi and Sumedang. In addition, I must thank my interviewees who provide lots of valuable information. During this research, I was happy to work with my colleague, Selvi and project leader, Dr. Noor Farikhah Haneda. Moreover, this thesis could be better owe to Prof. Dr. Ir. Iskandar Z. Siregar. His valuable comments during the thesis defense made abundant discussion. Great appreciation is also given to staff and colleagues from the Department of Silviculture, Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) for their contribution and help, and Mr. Ismail for help in secretariat work.

I want to express special appreciation to Professors in Seoul National University, Lee, Donkoo, Lee, Wooshin, Chung, Jusang, Youn, Yeo-chang and Lim, Sangjoon who recommended me to study in Indonesia and gave lots of support. Without their sincere advices, I would not start to study abroad with clear visions. I wish to give my gratitude to Park, Chong-ho, Acting Executive Director of ASEAN-Korea Forest Cooperation.

Finally, I would like to express my special thanks to my mother and father, my sisters: Hyeyoung Seo as well as all my friends for their support and persistent encouragement during my study.

Bogor, January 2013

TABLE

OF

CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES ... xiii

LIST OF FIGURES ... xiii

LIST OF APPENDICES ... xiii

1 INTRODUCTION 1

Background 1

Objective 2

Benefit 2

Research Structure 2

2 LITERATURE REVIEW 4

Jabon (Anthocephalus cadamba Miq) 4

Community Forestry in Indonesia 5

Silvicultural Practices of Jabon 6

Growth of Jabon 7

Uses of Jabon 8

3 METHOD 9

Time and Place 9

Material and Equipment 9

Research Process 10

Data Analysis 13

4 RESULT 14

Silvicultural Practices in Community Forest, West Java 14

Growth of Jabon in Community Forest, West Java 20

5 DISCUSSION 25

6 CONCLUSION 28

REFERENCE 29

APPEDICES 32

LIST

OF

TABLES

1 Site Information 10

2 Social information of stakeholders 15

3 Land preparation and planting activities in jabon plantation 17 4 Various types of fertilizers and frequency 17 5 Maintenance activities after planting including replanting, weeding and

pruning in West Java 19

6 Pest and disease control of jabon in West Java 19 7 Inventory data of Jabon in West Java 21 8 Dominant Height Growth Model Regression Coefficient 22 9 Site index classes and limiting values based on dominant height 23 10 DBH-Age equation depending on Site index classes 24

LIST

OF

FIGURES

1 Research Structure 3

2 Site quality class based on data from permanent plots in Java 7

3 Site map 9

4 Jabon plantation in Ciemas, 3.5 years old (Left) in Gadog 2 years

and 5 months old (Right) (Photo: private collection) 10 5 Measuring height with pole meter in Gadog (Photo: private collection) 11 6 Interview with planters in Sukabumi; the head of village in Kalibunder

(Left),Mr. Setiawan in Ciemans (Right) (Photo: private collection) 12 7 Chapman dominant height growth curve 22 8 Site index curve for jabon (3.5-year base age) in West Java. 23 9 DBH-Age equation based on SI classes 24

LIST

OF

APPENDICES

1 Questionnaire for jabon planter in local community 32

2 Forest inventory table 35

3 List of equipment 36

1

1

INTRODUCTION

Background

As a country with rich tropical forests, Indonesia has produced timber about 42 million m3 in 2010. This total timber production consists of 5.25 million

m3 of natural forests, 14.49 million m3 from land clearing and 18.56 million m3 of

plantation forests. The rest were from Perum Perhutani and other official licenses such as community forests (MoF 2012). Even though Indonesia is the largest tropical timber producer among ITTO countries, it also imports wood products including logs from other countries such as China, Japan, Malaysia and so on (ITTO 2011). As increasing GDP and domestic demands, Indonesia will suffer a shortage of wood supply ironically. Moreover, many areas of natural forests have been dramatically deforested and plantation forests also face serious social conflicts with local communities (Nawir and Santoso 2005). In addition, the Indonesian forest market will be affected by China, which becomes the largest forest market in terms of production, consumption and imports of wood products (Nilssona and Bull 2005).

Indonesia has some experiences in involving local people in plantation activities such as regreening (penghijauan) with community forest (MoF 2012) and community based forest management (Hutan Kemasyarakatan) (Van Noordwijk et al. 2011). These activities were designed to vitalize the local economy and compensate the shortage of wood supply from local community forests. Under the lack of wood supply, community forests can be an effective alternative and hence the Indonesia government has allocated 5.6 million ha of state production forests for community forest program (Hutan Tanaman Rakyat) (Emila 2007).

Recently, jabon (Anthocephalus cadamba Miq.), which is a native species to Indonesia, has been widely planted as a main tree species in community forests. For the first time, jabon has been planted in Kalimantan. Nowadays, jabon trees have also been planted everywhere not only community forests but also at mining rehabilitation areas, revegetation areas and industrial plantations because of its good adaptability and economic profitability (Soerianegara and Lemmens 1993; Mansur and Tuheteru 2010). Some general information on this species are available in various sources such as the internet, books and journals (Mulyana et al.; Mansur and Tuheteru 2010; Krisnawati et al. 2011; Wahyutomo 2011). However, it is hard for local communities to apply those methods in their own forest because it is too general and absence of specific examples. Moreover, it does not consider specific local conditions and cannot describe tree performance.

both researches had done in Kalimantan, so it does not fit Java area. For the local community who wants to plant jabon in Java, this research can provide references not only silvicultural practices and socioeconomic factors. In addition, it will be good basic data for further research of jabon by providing various performances of jabon in Java area.

Objective

- To document the existing silvicultural practices of jabon implemented by local communities in West Java

- To investigate tree growth performance among different sites in West Java - To examine the linkage of silvicultural practices and soil fertility for stand

quality

Benefit

- Local communities can improve their productivity in their forest by learning from other cases

- Various silvicultural practices of jabon can be collected by descriptive methods

- Understanding relation between growth performance of jabon and site conditions can be used as baseline data for future studies

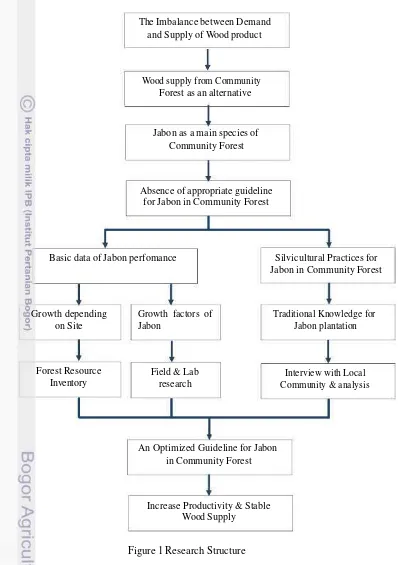

Research Structure

As shown Fig. 1, this research started to find an optimized guideline for jabon in the community forest. Jabon is one of important species in community forest to supply timbers and wood products in Indonesia. Because of imbalance between wood supply and demand, Indonesian government promoted community forest plantation as an alternative way to compensate lack of wood supply. Despite of its importance, it is hard to find appropriate guideline of jabon in the community forest.

In this research, there were two main important data: growth performance and silvlicultural practices of jabon. To find the data, forest inventory and lab analysis for growth performance have been implemented; in addition, oral and questionnaire interview has been done by the local community to collect silvicultural practices in the community forest

3

The Imbalance between Demand

and Supply of Wood product

Wood supply from Community

Forest as an alternative

Jabon as a main species of

Community Forest

Absence of appropriate guideline

for Jabon in Community Forest

Basic data of Jabon perfomance Silvicultural Practices for

Jabon in Community Forest

Growth depending

on Site

Forest Resource

Inventory

Growth factors of

Jabon

Field & Lab

research

Traditional Knowledge for

Jabon plantation

Interview with Local

Community & analysis

An Optimized Guideline for Jabon

in Community Forest

Increase Productivity & Stable

Wood Supply

2

LITERATURE

REVIEW

Jabon (Anthocephalus cadamba Miq)

Jabon is a tropical tree species in South Asia and Southeast Asia. This tree is called by various names in different countries such as kelempayan in Malaysia ; kadam and cadamba in Cambodia; kaatoan bangkal in the Philippines (Soerianegara and Lemmens 1993). In Indonesia, the local names of this species are: galupi, bengkal, johan kelampai, lampaian (Sumatra); jabon, jabun, hanja,

kelampeyan, kelampaian (Java); ilan, kelampayan, taloh, tawa, tuwak (Kalimantan); bance, bute, loeraa, sugi mania, toa (Sulawesi); gumpayan, kelapan, mugawe (Nusa Tenggara); aparabire, masarambi (Papua) (Martawijaya 1989).

Jabon is a native species in Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam. In addition, it can be found in Cambodia, Thailand, Timor Leste and Brunei, Myanmar and Laos. Because of its favorable characteristics for plantation, this tree species have been planted inside and outside of its native countries, such as Costa Rica, Puerto Rico, South Africa, Surinam, Taiwan, Venezuela and other tropical and subtropical countries (Orwa et al. 2009). Each country has specific local names for jabon. In this study, this tree species is called as jabon (Java) because this research will be conducted mostly in Java, Indonesia.

Jabon has good abilities to grow on various soil types. It is considered as a typical pioneer species that grows on deep, moist, alluvial sites, and swamps and flooded areas. However, jabon grows more abundantly and dominantly on fertile soils but does not grow well on leached and poor aeration soil conditions despite of other good conditions (Soerianegara and Lemmens 1993). Light is the most important factor for jabon’s growth, because jabon is sensitive to frost. Usually, the maximum temperature varies from 32 to 42 ℃ and the minimum from 3 to 15.5 ℃. The mean annual rainfall for jabon ranges from 1500 to 5000 mm, but some jabon in the central part of South Sulawesi grows locally on much drier sites like below 200 mm. The range of altitude is usually between 300 and 800 m above sea level. However, In the equator region, it is also found from just above sea level up to an elevation of 1000 m (Martawijaya 1989).

In terms of silviculture, jabon has many advantages; fast growing, good adaptability on a variety of soil types, and the absences of serious pests and diseases. Therefore, jabon can be used in reforestation and afforestation programs. It can improve soil conditions physically and chemically by adding large amounts of leaf and non-leaf litters which can increase cation exchange capacity, plant nutrients and organic matters. In addition, wood and extract from the tree can be used for medicine, furniture and so on (Mutua et al. 2009).

5 Community Forestry in Indonesia

Community forestry means the management of forest lands and products by local communities to meet their economic and, social needs (Roslinda 2008). However, the definition of community forestry has evolved from a narrow definition to a broader concept that covers social, economic and conservation (RECOFTC 2008). The community forestry has been applied to both developed and developing countries such as the Philippines, India, Nepal, Indonesia, Malaysia, England, New Zealand and United States of America (Bruce et al. 1989; Arnold 1991; Lynch 1995; Braganza 1996; Malla et al. 2003; Nawir and Santoso 2005; RECOFTC 2008; Van Noordwijk et al. 2011). Even though community forestry concept has been developed for a long time, there have been various similar terms that have the same meaning but a little bit different due to countries’ conditions such as languages, land tenure and policies.

In Indonesia, there are some terms related to community forestry such as Social Forestry (Kehutanan Sosial), Co-management of forestry (Pengelolaan Hutan Bersama), Collaborative Forest Management (Pengelolaan Hutan Kolaboratif), Community Based Forest Management (Pengelolaan Hutan Berbasis Masyarakat), Farm Forestry (Hutan Rakyat), and Community Forestry (Hutan kemasyarakatan) (Muhtaman et al. 2008). Those terms share common ideas of forest management with local communities but land ownership, community right to make a decision and purpose of forest management are totally different. In accordance with the Decree of the Minister of Forestry No. 101/KPR-V/1996, Hutan Rakyat is a kind of forest which grows in abandoned owned land or other types land with minimum area of 0.25 ha and more than 50 % of crown covers, 500 trees per hectare in the first year. Most of Hutan Rakyat is an artificial forest with other crops (agroforestry) and land property rights are owned by person, clan or group. In addition, Indonesian government tries to cooperate with local communities to manage Indonesian forest efficiently. In Government Regulations PP No. 6/2007 (Peraturan Pemerintah PP No.6/ 2007), there are four methods to manage the community forest (Hinrichs et al. 2008):

(1) Hutan Desa (Village Forest)

In Hutan Desa, permanent management rights are granted to village administration by the Minister of Forestry/Local Government. It is a similar approach to Community Based Forest Management like one in the Philippines. (2) Kemitraan (Partnership)

Kemitraan means a partnership that local community can work together with who has forest utilization right. Partner can be a business person, company or nearby villagers.

(3) Hutan Tanaman Rakyat (Community Plantation Forest)

For Community Plantation Forest, the government gives access to the local community for using protected natural resources and provides credits and market opportunities. Households also can plant various species trees for timber and apply for permission for a timber utilization maximum for 100 years. Also, there can apply for the permission as individuals, cooperatives, government owned enterprises, private company and various forms. (4) Hutan Kemasyarakatan (Community Forestry)

means forests which are allocated to local community groups such as cooperatives or groups of citizens. Regent (Head of District) can issue permission for utilization of forest products and timber (called IUPHHK) for 35 years based on forest management plan developed by the forestry service. This study is focused in private woodlands (hutan rakyat or hutan milik) because this information (especially in Java) is useful for whom are interested in planting jabon trees at their own lands and for government officers who needs a guidance for jabon plantation through the Hutan Kemasyarakatan Program. The community forests in Java provide valuable resources - because 50 % of the community forest in Indonesia are located in Java island (Hinrichs et al. 2008). In addition, the Indonesian government has also invested some funding to establish a 4,465 ha community-owned forest management model in Java (West, East and Central Java) from 2006 to2010 (MoF 2012). Therefore, understanding private woodlands in Java will be meaningful when the government or local community extends their plantation activities with jabon tree.

Silvicultural Practices of Jabon

Silviculture involves the methods for establishing and maintaining communities of trees and other vegetations that have value to people and also ensures the long-term continuity of essential ecological functions, and the health and productivity of forested ecosystems. Silviculture is not just science or technique but more complicated art. It consists of whole activities related to forestry from species selection to marketing (Nyland 1996).

Silvicultural practices refer to every practice for achieving silvicultural goals. Usually, it consists of establishing and maintaining processes (Nyland 1996). For examples, whole activities before planting can be established process such as seed collection, seed preparation, sowing, site preparation and planting. After planting, maintenance activities such as weeding, fertilizing, thinning, pest and disease control will be followed. Even though these silvicultural practices are very essential to tree growth, lack of silvicultural practices is often encountered because of the limitations of farmer’s silvicultural knowledge (Byron 2001).

In the case of jabon, there have been some researches and books about silvicultural practices and guidance for local communities (Lamprecht 1989; Mulyana et al. ; Mansur and Tuheteru 2010; Mansur and Surahman 2012; Wulandari et al. 2012). However, it is still hard to find simple and easy-to- understand guidances for the local community who wants to plant jabon in Java. Furthermore, there are many farmers have suffered difficulties to plant jabon with adequate silvicultural practices and consultations. Compared to other plantation species such as mahogany and teak, information about jabon plantation is still lacking (Pramono et al. 2010; Krisnawati et al. 2011).

7 Growth of Jabon

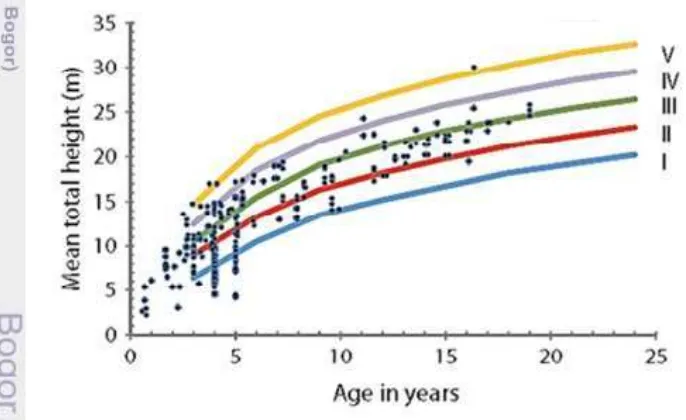

Tree growth is considerably important for planters who want to plant jabon in their field because it is directly related to productivity. According to Krisnawati et al. (2011), there are extremely few reliable data to predict the growth and yield potential of jabon in Indonesia. In their research, they collected inventory data from young stands (up to 5 years old) from 92 temporary plots in South Kalimantan and old stands from 26 permanent plots in Java. In addition, preliminary reports are used (Fig.2).

According to Sudarmo (1957), jabon plantations growing in several sites, Java can reach a mean annual increment (MAI) of 20 m3/ha/year by age of 9 years

in good-quality sites and 16 m3/ha/year in medium-quality. In case of poor-quality

site, it may not reach 15 m3/ha/year even up to 24 years. According to Zuhaidi et

al (2012), the growth of jabon in Sabah, Malaysia can reach a MAI of 29 m3/ha/year by age of 4 years and 55 m3/ha/year by age of 10 years in Tawau,

Sabah. In Puerto Rico, the 12.5-year-old plantation had a volume growth of 27.8 m3/ha/year (Lugo and Figueroa 1985).

Determining the rotation period depends on the purpose of production. According to Soerianegara and Lemmens (1993), 4-5 years after planting can be harvested for pulp wood but it will take approximately more than 10 years for wood production. In state-owned plantations in Java, according to decree by the director of Perum Perhutani (Decree No. 378/Kpts/Dir/1992; Perum Perhutani 1995), the economic rotation for jabon is about 20 years.

Figure 2 Site quality class based on data from permanent plots in Java (Sudarmo 1957; Suharlan et al. 1975)

Uses of Jabon

Jabon has the soft, light colored wood with the density in the range 290- 560 kg/m3 at 15% moisture content. It is easy to process with hand and machine

tools, split and peel. However, it is not durable when used for outdoor construction or in contact with the ground (Soerianegara and Lemmens 1993; Lamprecht 1989).

The wood is well-suited for various end uses, such as plywood, light construction materials and tea crates, toys, matches, chopsticks. It is also easy to pulp but difficult to bleach for paper production. For fuel wood and for charcoal, jabon is unsuitable (Soerianegara and Lemmens 1993; Lamprecht 1989).

The trees are also suitable for ornamental purpose and shade along roadsides and villages as well as for agroforestry systems. It is also used in reforestation and afforestation programs in Indonesia. As a native species, it can improve some of the physical and chemical properties of the soil and increase the level of the soil organic carbon and nutrients by adding the large amounts of leaf and non-leaf litters (Orwa et al. 2009).

9

3

METHOD

Time and Place

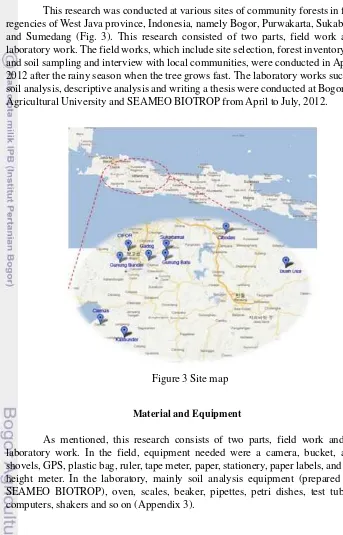

This research was conducted at various sites of community forests in four regencies of West Java province, Indonesia, namely Bogor, Purwakarta, Sukabumi and Sumedang (Fig. 3). This research consisted of two parts, field work and laboratory work. The field works, which include site selection, forest inventory and soil sampling and interview with local communities, were conducted in April, 2012 after the rainy season when the tree grows fast. The laboratory works such as soil analysis, descriptive analysis and writing a thesis were conducted at Bogor Agricultural University and SEAMEO BIOTROP from April to July, 2012.

Figure 3 Site map

Material and Equipment

Bunder 435 2500-3000 24-28

Jonggol Sukadamai

Sukabumi Kalibunder

Research Process

Site Selection

The site selection process was the first step to start this research as well as the most important thing to make this research informs. However, it was hard to find the location of jabon plantation and to select some sites. Even though there are many jabon plantations in West Java, there was no information about their locations and owners from government institution and local office. Moreover, West Java is too wide to visit and research whole areas. Therefore, this research only selected 20 community forest sites located 13 sites in Bogor, 3 sites in Sukabumi, 1 site in Sumedang and 3 sites in Purwakarta (Table 1) based on discussion with advisors and some contacts with local community and local forestry agency (Dinas Kehutanan).

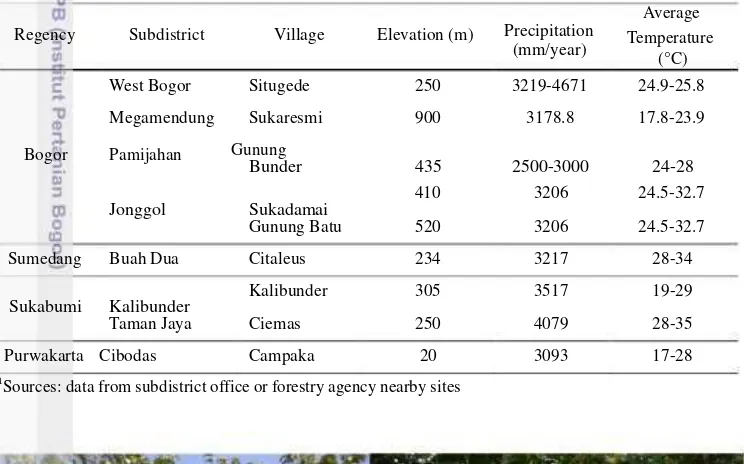

Table 1 Site Informationa

Regency Subdistrict Village Elevation (m) Precipitation (mm/year)

Average Temperature

(°C) West Bogor Situgede 250 3219-4671 24.9-25.8 Megamendung Sukaresmi 900 3178.8 17.8-23.9 Bogor Pamijahan Gunung

410 3206 24.5-32.7 Gunung Batu 520 3206 24.5-32.7 Sumedang Buah Dua Citaleus 234 3217 28-34

Kalibunder 305 3517 19-29 Taman Jaya Ciemas 250 4079 28-35

Purwakarta Cibodas Campaka 20 3093 17-28

a Sources: data from subdistrict office or forestry agency nearby sites

11 Site Inventory

The purpose of site inventory was to evaluate and analyze jabon stands quality. In this research, simple site inventory was implemented including height, diameter, and ages and clear-bold. From the clear-bold, we could be calculated commercial volume of jabon and self-pruning ability could be noted. Stand inventory was implemented by random sampling method. There were three replicates with 0.02 ha or 0.04 ha sample plot in each site. To describe site more specifically, planting pattern also was observed such as spacing, agroforestry and homogeneity of tree height. From this forest inventory, total stand volume, merchantable volume of a stand and stand quality could be evaluated.

Figure 5 Measuring height with pole meter in Gadog

Soil Sampling

The composite sampling method was applied to collect soil samples for analyses. However, only one sample in each site was collected because most sites have relatively similar conditions. Each sample was collected by soil borer with 30 cm depth. The soil samples were then stored in plastic bags to keep their conditions, which were then analyzed in SEAMEO BIOTROP using a standard procedure. In addition, only five parameters that were considered as important factors in this study are analyzed such as N, P, K, C-organic, and soil texture. The soil conditions provided valuable information for evaluating the growth performance of jabon in addition to silvicultural practices and environmental conditions.

Interview with Local Community or Owner

Questionnaire consisted of two parts, i.e. socioeconomic and silvicultural practices to investigate both factors (Appendix 1). In the socioeconomic part, there were some questions focused on the planter’s background and motivation of planting jabon. In the silvicultural practices part, most of the questions focused on silvicultural practices in terms of quantitative and qualitative aspects. These question lists referred to the previous community forestry researches (Pribadi 2001; Kallio, Krisnawati et al. 2011).

13 Data Analysis

Silvicultrual Practices

The analysis of silvicultural practices was based on the results of the questionnaire. The main purpose of this analysis was to document the existing silvicultural practices and to understand the present situation in the field. In this research, these data were categorized into five tables: one for socioeconomic aspect and four silvicultural practices. Each table presented quantitative and qualitative information based on the results of interviews. Such data tabulation was further analyzed to provide more detailed descriptions and comparison among various sites of community forests.

Growth of Jabon

4

RESULT

Silvicultural Practices in Community Forest, West Java

Stakeholders

To explore silvicultural practices in West Java, these interviews have been done with 9 different practitioners or owners in West Java areas. Through interviews, there are some findings (Table 2). Firstly, planting jabon is considered as an investment with economic purposes. That’s why most of jabon plantations are owned by outsiders not local communities such as Jakarta or closed to villages. Those jabon plantations can be categorized into three types based on management types: partnership, hiring employees and direct management. In case of partnership, it is called ‘kemitraan’ which is similar to cooperative management. If investors provide seedling, fertilizer and seed-money, farmers or local communities provide land and manpower for planting jabon. After harvest trees, they divide their profit from trees depending on their contributions. Another type is hiring an employee. It seems like ‘partnership’ but it is totally different. Farmers are just hired and paid to maintain jabon plantation. The last type is the direct management by owner. In Gunung Bunder, Gunung Batu and Purwakarta, those owners directly manage their plantation by hiring daily workers and regularly visiting the place. The most different thing about hiring or partnership is that the investor or owner is highly participating in managing the plantation area.

Second, the information on silvicultural practices of jabon is still lacking. Even though many of them plant jabon for profits, they did not take any kinds of silvicultural training and just learnt from other planters or own experience. Most practitioners planted jabon trees with their own experience from Sengon (Paraserianthes falcataria) or other plants. Owners also just order farmers or hired employee to plant jabon trees without specific guidelines or directions.

Table2Socialinformationofstakeholders

Name

Tohir Rama Suheri Irmawati Setiawan

Aton

Munji Arwin Warno

50's 20's 30's

Elementary Bachelor Elementary

N N N 50's Elementary N 30's

30's 30's 50's 50's

N/Ad

Diploma Bachelor

N/A N/A

Ne

Y(AfterPlanting) N N N

Age Education Silviculturaltraining Motivation

Economic Economic Economic Economic Economic Sites Position

Partnera Employeeb

Owner Owner

Managerc

Learning practices OtherPlanters OtherPlanters OwnExperience

Internet OwnExperience Situgede

Gadog

GunungBunder GunungBatu Sukabumi-Ciemas Sukabumi- Kalibunder Sukadamai Purwakarta Sumedang

OwnExperience Farmer'sgroup OwnExperience

Employee OwnExperienceEconomic/Promotionf

Economic Economic Economic Manager

Owner Employee

MrTohirhasworkedasapartnerincaseof‘Kemitraan’whichinvestorprovidesseedlingandfertilizerandheworks.Aftertheyharvesttrees,theyshare profitstogether

b MrRamaisworkinginthefloriculturecompany

c

WheninvestorswanttoplantJabon,theyworkasamanagerwhosupervisesandcoordinateslocalfarmersorcommunity

d Dataarenotavailable

e

Theyhaveneverbeentrainedbefore

f

InKalibunder,theheadofavillageownsjabonplantation,sohewantstopromotejabonforlocalcommunities

a

Silvicultural Practices

As mentioned, silvicultural practices mean every type of practices to achieve silvicultural or owner’s goals. In this research, whole silvicultural practices are divided into eight steps like land preparation, planting and fertilizing, infilling and weeding, pruning and pest, disease controls, thinning. Different from my expectation, most managers have similar silvicultural practice patterns which maybe has stemmed from traditional knowledge or their own experiences. Unfortunately, thinning practices have never been done before because this research sites have only younger trees less than 3.5 years.

(1) Land preparation and planting

Land preparation is a first step for planting jabon. Usually, there are two methods: whole and part. In West Java, the whole land preparation method is more dominant with cost ranging two million to two and half million rupiah per ha. Unfortunately, many of them did not know how much they have spent for land preparation. In case of the sites at Situgede, he cleared land by himself so there is no cost. In Purwakarta, the land was already open because it was ex-rice field so it did not need land preparation.

All practitioners planted seedling of jabon from various sources. Many of them bought their seedling from private nurseries. The price and size of seedling varies. The price ranges from 1000 to 5000 rupiah and size of seedling ranges from 15 to 80 cm. Before planting trees, they dug planting hole with various sizes. Most of them prefer to 40×40×40 cm and others just dug 10 or 15 cm size. In case of spacing, there were found 3×3 m but still there are many variations too such as 2×2 m, 2×2.5 m and 2.5×2.5 m (Table 3).

(2) Fertilizing

Table3Landpreparationandplantingactivitiesinjabonplantation

Cost

(Rupiah/Ha) Plantingsources

Seedling(Private) Seedling(Dinas) Seedling(Malang) Seedling(N/A) Seedling(N/A) Seedling(Private) Seedling(Private) Seedling(CIFOR)

Seedling(Private) 1500 40 20×20×10

- N/Ab

2.5Million N/A N/A N/A 2Million -N/A Spacing(m)

3×3 3×3

2×2.5,3×3,3×2.5

2.5×2.5,3×3,2×2

2×2.5 2.5×3

2×2,2.5×2,2.5×2.5

3×2.5

3×3

Sites Land

Clearing Situgede Gadog GunungBunder GunungBatu Sukabumi-Ciemas Sukabumi-Kalibunder Sukadamai Purwakarta Whole Whole Whole Whole Whole Partial/Whole Whole Whole Priceof Seedling a (Rupiah) 5000 N/A 1500 1500 1500~2000 1500~5000 2500 1000 Sizeof Seedling (cm) 40~50 40~60 30~80 30 15 30~50 30~50 30~40 Planting HoleSize (cm)

30×30×30

40×40×40

30×30×40

40×40×40

10×15×10

30~80

40×40×40

20×20×20

Sumedang Whole

a b IndonesianRupiah(1USD=9600IDR) Notavailableinformation Table4Varioustypesoffertilizersandfrequency N,P,K Y(N/A) 100g/tree 200g/tree Y(N/A)

Y(N/A)

(3) Maintenance

The rate of replanting is closely related to the rate of mortality. In this research, the mortality of jabon tree ranges from 2 to 50 percentages. According to sites Gunung Bunder and Purwakarta’s case, they suffered high mortality of seedling during the dry season due to lack of water supply. After they found wilted seedling, they replanted as soon as possible. However, the owner of Gunung Bunder said that the growth of the replanted seedlings could not catch up with others unless they have been planted before the six – month (Table 5).

Averagely, weeding practices were carried out every three or four months. However, it is also depending owner’s decision and growth of Jabon. Most managers carried out weeding practices with a sickle but the owner of jabon plantation in Sumedang has used chemical methods with Amoxan and Sandup mixture (five-liter per hectare. 1:4 mix ratio).

As many people know, Self-pruning is one of jabon’s characteristics. Of course, many managers already knew about it so they did not do any pruning methods. However, in Situgede, Gadog and Gunung Bunder, they already pruned 25 percent of branches. According to the manager of Gadog site, their jabon tree could not self-pruning so he inevitably decided to do the pruning. Otherwise, the manager in Gunung Bunder said that he decided to do pruning if he thought there is economic value. He also spent 300,000 rupiah per hectare every six-month for pruning activity (Table 5).

(4) Pest and Disease

Table5Maintenanceactivitiesafterplantingincludingreplanting,weedingandpruninginWestJava Replanting Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Frequency Notregular 2~3times/year 3times/year 4times/year 4times/year Notregular 3times/year Everymonth b 4times/year,herbicide Cost(Rupiah/ha) N/A N/A 1.2million 1.5million N/A N/A 3miliion N/A N/A Weeding Pruning Y(onlyfirstyear) Y(25%) Y(6month/0.3millionperha) N N Y N N N

Sites Mortality(%)

Situgede Gadog GunungBunder GunungBatu Sukabumi-Ciemas Sukabumi-Kalibunder Sukadamai Purwakarta Sumedang 10 3 a 20~30 20 30 30 10~15 a 10~50 2 a b Whentheysufferedhighmortality,theyplantedseedlingduringdryseason AmoxanandSandupmixture(five-literperhectare.1:4mixratio) Table6PestanddiseasecontrolofjaboninWestJava

Typeofpest Frequency

Notoften Notoften Rarely Rarely Notoften Notoften Protectionmethods Preventing Furadan Furadan:200g/tree Furadan:50-100g/tree Furadan:50-100g/tree N N Control Insecticide Insecticide Mechanical Insecticide N N Sites Situgede Gadog GunungBunder GunungBatu Sukabumi-Ciemas Sukabumi-Kalibunder Sukadamai Purwakarta Notoften Rarely Rarely Furadan:50-100g/tree N N Insecticide N Insecticide Sumedang

Arthroschistahilaralis,Attacusatlas,Melolomthinatesp.

Arthroschistahilaralis,1stem-borerunidentified

a

Arthroschistahilaralis,Attacusatlas,moduzaprocris,2UI

Arthroschistahilaralis,Melolomthinatesp.

Arthroschistahilaralis Arthroschistahilaralis

Arthroschistahilaralis,Attacusatlas,Moduzaprocris,

bagworms,Melolomthinatesp.

Arthroschistahilaralis,Thyridopteryxephemeraeformis Arthroschistahilaralis,Attacusatlas,Moduzaprocris,

Melolomthinatesp.

Growth of Jabon in Community Forest, West Java

Inventory of Jabon in West Java

In West Java, there were 20 sites have been selected to conduct forest stand inventory with 0.02 ha or 0.04 ha size of plot except Situgede. In addition, each site has been forest inventoried with three-repetition including two-census sites, Situgede. There are totally 56 plots have been inventoried in 20 sites, West Java. In Situgede, all of jabon trees have been measured to see how different growth rate between optimal condition and ex-rice field in the same treatments. As shown in Table 7, the age of jabon tree ranges from 0.5-year to 3.5-year because jabon tree has been introduced in West Java from 2008. The mean diameter ranges from 2.45 cm to 14.57 cm with maximum 29.3 cm and the mean height of 1.29 m to 12.62 m with maximum 18.68 m in Situgede.

Each site soil sample has been analyzed in the SEAMEO Biotrop, Bogor. There are six parameters had been analyzed such as pH, organic compounds (C organic), total Nitrogen, Available Phosphorus, Available Potassium and texture. Most soil has clay texture except Gadog area, Sandy Loam in West Java. Overall, soil pH ranges from 4.2 to 6.1.

Site Classification

Forest site quality refers to the sum of factors which influence the capacity of production in the forest. Therefore, site quality correlates closely with timber production. Usually, site quality is measured by site index (SI) based on the mean height of dominant trees in permanent sample plots (PSP) However, there are no permanent sample plots and long term data for jabon because this research is based on exploratory field surveys and lack of jabon data in West Java. Therefore, in this case, the site index curves from temporary sample plots apply to determine site quality of jabon plantation in West Java in the same way as usual.

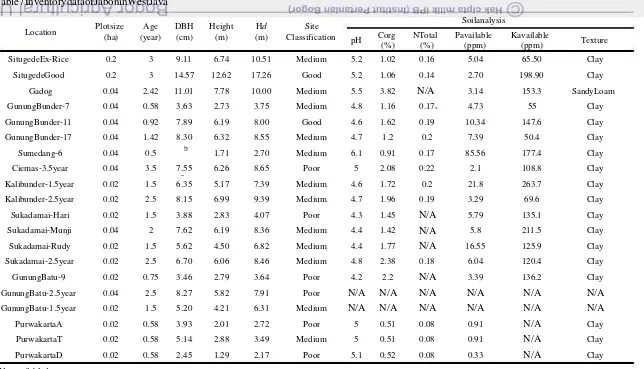

Table7InventorydataofJaboninWestJava Soilanalysis pH 5.2 5.2 5.5 4.8 4.6 4.7 6.1 5 4.6 4.7 4.3 4.4 4.4 4.8 4.2 1.42 1.77 2.38 2.2 1.45 1.96 1.72 0.2 0.19 2.08 0.22 0.91 0.17

1.2 0.2 7.39 85.56 2.1 21.8 3.29 5.79 5.8 16.55 0.18 6.04 1.62 0.19 10.34 1.16 0.17 4.73 3.82

1.06 0.14 2.70 3.14 55 147.6 50.4 177.4 108.8 263.7 69.6 135.1 211.5 125.9 120.4 198.90 153.3 1.02 0.16 5.04 65.50 Corg

(%) NTotal (%) Pavailable (ppm) Kavailable (ppm) Texture Clay Clay SandyLoam Clay Clay Clay Clay Clay Clay Clay Clay Clay Clay Clay DBH (cm) 9.11 14.57 11.01 3.63 7.89 8.30 -7.55 6.35 8.15 3.88 7.62 5.62 6.70 3.46 8.27 5.20 3.93 5.14

2.45 1.29 2.17 2.88 3.49 2.01 2.72 4.21 6.31

5.82 7.91 Poor Medium

Poor Medium

Poor 2.79 3.64 Poor 6.06 8.46 Medium 4.50 6.82 Medium 6.19 8.36 Medium 2.83 4.07 Poor 6.99 9.39 Medium 5.17 7.39 Medium 6.26 8.65 Poor

b Location 6.74 12.62 7.78 2.73 6.19 6.32

1.71 2.70 Medium 8.55 Medium 8.00 Good 3.75 Medium 10.00 Medium 17.26 Good 10.51 Medium Plotsize

(ha) (year) Age Height (m) (m) Hd Classification Site

SitugedeEx-Rice 0.2 3 SitugedeGood 0.2 3

Gadog 0.04 2.42 N/A

a GunungBunder-7 0.04 0.58

GunungBunder-11 0.04 0.92 GunungBunder-17 0.04 1.42 Sumedang-6 0.04 0.5 Ciemas-3.5year 0.04 3.5 Kalibunder-1.5year 0.02 1.5 Kalibunder-2.5year 0.02 2.5

Sukadamai-Hari 0.02 1.5 N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Sukadamai-Munji 0.04 2 Sukadamai-Rudy 0.02 1.5 Sukadamai-2.5year 0.02 2.5

GunungBatu-9 0.02 0.75 3.39 136.2 Clay

GunungBatu-2.5year 0.04 2.5 GunungBatu-1.5year 0.02 1.5

N/A N/A 5 5 5.1 N/A N/A 0.51 0.51 0.52 N/A N/A 0.08 0.08 0.08 N/A N/A 0.91 0.91 0.33 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Clay Clay Clay PurwakartaA 0.02 0.58

PurwakartaT 0.02 0.58 PurwakartaD 0.02 0.58

a

b Notavailabledata Nodatabecauseitistooyoung

H a

This model has been calculated by Sigma Plot program 10.0 version

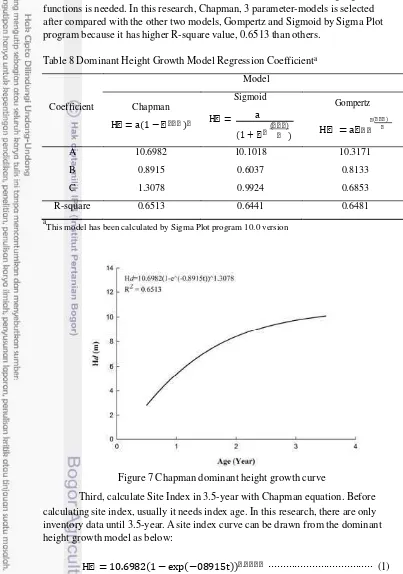

Second, the most reasonable model to fit mean dominant height growth functions is needed. In this research, Chapman, 3 parameter-models is selected after compared with the other two models, Gompertz and Sigmoid by Sigma Plot program because it has higher R-square value, 0.6513 than others.

Table 8 Dominant Height Growth Model Regression Coefficienta

Model

Coefficient

Chapman

H a

Sigmoid

H a

Gompertz

A 10.6982 10.1018 10.3171

B 0.8915 0.6037 0.8133

C 1.3078 0.9924 0.6853

R-square 0.6513 0.6441 0.6481

a

Figure 7 Chapman dominant height growth curve

Third, calculate Site Index in 3.5-year with Chapman equation. Before calculating site index, usually it needs index age. In this research, there are only inventory data until 3.5-year. A site index curve can be drawn from the dominant height growth model as below:

H . exp t . ··· (1)

[image:34.612.63.466.91.665.2]

23

a H/ exp . . ··· (2)

After calculating ‘a’ coefficient, each plot can calculate Site Index at index age, 3.5-year in the same way like (1) equation as below:

a exp . . . or a exp . . ·· (3)

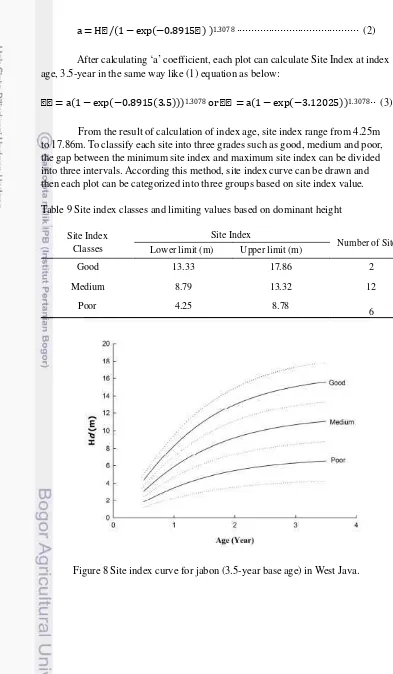

From the result of calculation of index age, site index range from 4.25m to 17.86m. To classify each site into three grades such as good, medium and poor, the gap between the minimum site index and maximum site index can be divided into three intervals. According this method, site index curve can be drawn and then each plot can be categorized into three groups based on site index value.

Table 9 Site index classes and limiting values based on dominant height

Site Index

Classes

Site Index

Lower limit (m) Upper limit (m)

Number of Sites

Good 13.33 17.86 2

Medium 8.79 13.32 12

Poor 4.25 8.78

6

[image:35.612.92.485.59.733.2]

Growth Equation based on Site Quality

After categorizing sites into three grades, growth equations for DBH and Height can be drawn by using the Chapman regression model as below:

Table 10 DBH-Age equation depending on Site index classes

Site Index Classes

DBH

Equation R-square

Good DBH = 850.057(1-exp(-0.0002t))0.5374 0.9214

Medium DBH = 15.4515(1-exp(-0.1874t))0.5991 0.6594

Poor DBH = 305.734(1-exp(-0.0002t))0.5050 0.7971

[image:36.612.39.469.49.749.2] [image:36.612.41.478.93.772.2]

25

5

DISCUSSION

As shown in Table 2, many people planted jabon with economic motivation but ironically nobody has taken any kinds of silvicultural training before they planted trees. Most of them learned silvicultural practices from their own experience or other planters. In Kallio et al (2011) research in Kalimantan, there was only 21 % farmers had taken silvicultural training even though 97 % of them mentioned economic motivation for tree planting. They also learned silvicultural practices from other planters (45 %) or own experience (31 %). Although both research sites and management types are different, lack of silvicultural training and economic motivation for tree planting are similar. However, most planters implemented silvicultural practices relatively well in both cases (Kallio et al 2011). In Kallio et al (2011), most farmers implemented more than three practices with no regard to farmer’s attitude towards tree planting. It seems that economic motivation and their own experience have led them to implement practices. In spite of their well-maintenance, it is true that silvicultural training and knowledge for jabon are still lacking for planters. In Kallio et al (2011), there were no four farmers learned practices from government and this research too. According to Salam et al. (2010), forest extension activities can have a positive effect on planting trees. In Kallio et al (2011), mahogany planters who received training always implemented the recommended practices. In case of jabon planters, farmers who had been members of the farmer’s group for a long time were more active in silvicultural management because interaction with other farmers is found to encourage better farming practices (Kallio et al 2011; Bebbington 1996). Therefore, silvicultural practices and support of farmer’s group can be motivators for jabon planters.

In Table 3, all farmers planted trees from seedlings ranging 15~80 cm. The price of seedling also varied from 1000 to 5000 rupiah. According to Mansur and Tuheteru (2010), the price of seedlings ranged from 2500 to 7500 rupiah in 2009 and they predicted that the price will decrease approximately 750 to 1500 rupiah. In addition, they recommended good seedling which has 25-30 cm height and approximately 0.5 cm diameter while Krisnawati et al (2011) suggested seedling with 30-40 cm height and around 1 cm diameter. However, some planters bought too cheap (Purwakarta) or small seedlings (Ciemas). Those inappropriate seedlings can cause high mortality rate (Table 5). In Krisnawati et al (2011), fertilizers are required to attain optimal growth in infertile land so in South Kalimantan, Urea and Triple Super Phosphate (TSP) were widely used more than once during the first two years. In Table 4, in West Java, NPK, animal manure and Urea were widely used but TSP was only in Gunung Batu. According to Soerianegara and Lemmens (1993), using 15 g of urea per seedling resulted in much faster growth. In terms of fertilizers, there are some researches from Bogor Agricultural University (Wulandari et al 2011; Mansur and Surahman 2011; Supriyanto and Fiona 2012).

and height are smaller than South Kalimantan but the maximum diameter and height are bigger. As Krisnawati et al (2011) said the growth rates of both diameter and height in Java higher than those in South Kalimantan. Even though stand ages ranged from 0.5 years to 3.5 years, the maximum values are higher and other mean values are not different.

Based on the site index curve drawn from temporary sampling plots in West Java, 20 different sites are categorized into three groups, good, medium and poor. In Table 9, there are two sites categorized into good, six sites into poor and others into the medium.

Although site index curve for jabon in Table 7 derived from 0.5 to 3.5 years old plantations, it could be useful data to estimate future productivity by comparing with the existing data such as Fig. 2. By comparing with Fig. 2, site index curve for jabon in Fig. 7 can match site index class and estimate the future growth rate in the long term. For example, site index of good site class ranged from 13.33 m to 17.86 m can match with site class to . According to Sudarmo (1957), several jabon plantation in Java could reach a maximum volume mean annual increment (MAI) of 20 m3/ha/year by the age of 9 years in good

quality site. In medium quality site, MAI of 16 m3/ha/year can be attained in 9

years but the only MAI of 13 m3/ha/year can be attained at the age of 24 years in

poor quality sites.

In this research, only good and poor sites are compared to make the differences clear with two criteria, silvicultural practices and site conditions including soil. In the aspect of silvicultural practices between good and poor, it seems that there are no significant differences. The only differences are noticed in fertilizing and pruning practices (Table 4, Table 5). Ironically, poor sites have paid more attention to fertilizing. They tend to use more or frequently fertilizer compared with good site. Maybe, poor growth of jabon drives practitioners to care about fertilizing. One more interesting thing is that good site has done with pruning practice at least once or more. Generally, jabon does not need to do pruning practices because of its self-pruning characteristics. It is hard to find the effect of silvicultural practices on each site because most of them have implemented similar practices.

27 close sites even though soil conditions are same. The only different thing is that this site implemented agroforestry with red pepper.

As mentioned above, there are still many people plants jabon for economic motivation. For successful plantation, there are some important things to know as the results of this research. First of all, they need training including basic knowledge of silviculture and forestry. Few people have ever studied forestry or related fields, so in reality they need even basic information such as measuring height and diameter or selecting good seedling. Government can support extension program for investors as well as local farmers. Second, site selection is very important. Unfortunately, many investors or farmers planted jabon in their empty land because other planters planted. However, site conditions must be considered before they decided to plant trees. According to Zuhaidi et al (2012), jabon may not be suitable in higher elevation or not associated with water. This research showed similar results that favorable growth rate was shown in Situgede closed to ponds. Moreover, other