Severe mood problems in adolescents

with autism spectrum disorder

Emily Simonoff,

1Catherine R.G. Jones,

2Andrew Pickles,

3Francesca Happe

´,

4Gillian Baird,

5and Tony Charman

61Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry and NIHR Biomedical

Research Centre for Mental Health, De Crespigny Park, London, UK;2Department of Psychology, University of Essex,

Wivenhoe Park, Colchester, Essex, UK;3Department of Biostatistics, King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry,

London, UK;4MRC SDGP Research Centre, King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK;5Guy’s & St

Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, Newcomen Centre, London, UK;6Centre for Research in Autism and Education,

Institute of Education, London, UK

Introduction:Severe mood dysregulation and problems (SMP) in otherwise typically developing youth are recognized as an important mental health problem with a distinct set of clinical features, family history and neurocognitive characteristics. SMP in people with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) have not previously been explored. Method:We studied a longitudinal, population-based cohort of adolescents with ASD in which we collected parent-reported symptoms of SMP that included rage, low and labile mood and depressive thoughts. Ninety-one adolescents with ASD provided data at age 16 years, of whom 79 had additional data from age 12. We studied whether SMP have similar correlates to those seen in typically developing youth. Results:Severe mood problems were associated with current (parent-rated) and earlier (parent- and teacher-rated) emotional problems. The number of prior psychiatric diagnoses increased the risk of subsequent SMP. Intellectual ability and adaptive functioning did not predict to SMP. Maternal mental health problems rated at 12 and 16 years were associated with SMP. Autism severity as rated by parents was associated with SMP, but the relationship did not hold for clinician ratings of autistic symptoms or diagnosis. SMP were associated with difficulty in identifying the facial expression of surprise, but not with performance recognizing other emotions. Relationships between SMP and tests of executive function (card sort and trail making) were not significant after controlling for IQ. Conclusions:This is the first study of the behavioural and cognitive correlates of severe mood problems in ASD. As in typically developing youth, SMP in adolescents with ASD are related to other affective symptoms and maternal mental health problems. Previously reported links to deficits in emotion recognition and cognitive flexibility were not found in the current sample. Further research is warranted using categorical and validated measures of SMP. Keywords: Severe mood dysregulation, mood disorders, childhood autism, autism spectrum disorder, SNAP.

Introduction

Severe mood problems (SMP) in children and ado-lescents include high levels of irritability, often manifested by temper tantrums, as well as low and labile mood; together, these have been identified as an important cause of psychosocial impairment. Debate has raged about the aetiology of mood dys-regulation symptoms, most specifically the extent to which these are best conceptualized as part of the spectrum of juvenile bipolar disorder, attention def-icit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or as a separate syndrome (Leibenluft, 2011). Leibenluft Cohen, Gorrindo, Brook, & Pine, (2006) argue persuasively for a new diagnostic category, severe mood dysre-gulation (SMD), currently under consideration for DSM-5 (www.dsm5.org). Under current proposals, SMD would include severe and prominent mood abnormalities, hyperarousal and increased reactivity to negative emotional stimuli, with consequent

functional impairment. In support of this new diag-nosis, Leibenluft and colleagues provide evidence for distinctive presenting and longitudinal clinical fea-tures, family history and neurocognitive profile (Lei-benluft, 2011). They argue that, while features aligned with irritability are included in several diag-nostic categories, the syndrome of severe and impairing irritability with predominant negative mood includes features not adequately captured by other diagnoses. Unlike classic juvenile bipolar dis-order, manic episodes do not appear to be common adult outcomes in SMD (Brotman et al., 2006), whereas unipolar depression and anxiety are (Stringaris et al., 2009). One small family study failed to find elevated rates of bipolar disorder in parents of children with SMD, in contrast with the parents of children with juvenile bipolar disorder (Brotman et al., 2007). Neurocognitive differences exist in young people with SMD in relation to: labelling facial emotions (Guyer et al., 2007); response to frustration (Rich et al., 2011); and performance on response reversal paradigms Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

(Dickstein, Finger, Brotman, et al., 2010), with neural circuitry differences on fMRI from juvenile bipolar disorder patients in the first two tasks (Brotman et al., 2010; Rich et al., 2011).

There has recently been an appreciation that other psychiatric problems frequently occur in people with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), with rates as high as 60–70%. These co-occurring disorders include high rates of ADHD, anxiety and ODD in children (Joshi et al., 2010; Leyfer et al., 2006; Simonoff et al., 2008). The emergence and timing of different psychiatric problems in ASD has not been explicity studied, but comparison of cross-sectional studies of different age groups suggests that depressive and obsessive-compulsive disorder may be more common in older adolescents and adults (Bakken et al., 2010; Mazefsky et al., 2010) and one longitudinal clinical study showed that affective disorder was amongst the most common newly emerging psychiatric disorders in adults with autism (Hutton, Goode, Murphy, Le Couteur, & Rutter, 2008). Affective disorders in autism have included bipolar disorder (Bradley & Bolton, 2006; Munesue et al., 2008), although the ascertainment methods and sample sizes in these studies do not provide a conclusion on whether bipolar disorder is dispro-portionately increased in ASD.

Most of the research on co-occurring psychiatric symptoms and disorders in people with ASD has used standardized instruments to measure recog-nized symptom patterns and diagnoses. The syn-drome of SMD has not, to our knowledge, been previously explored. There are several reasons to consider this a useful concept to explore in people with ASD. First, several of the symptom domains that are increased in people with ASD, including ADHD and affective disorder, have been associated with SMD. Second, people with ASD have high levels of psychosocial impairment that are greater than would be expected based on their level of intellectual functioning. While this has often been attributed to the core autistic deficits, it is an empirical question whether co-occurring psychiatric problems, such as SMD, contribute to this psychosocial impairment. Third, the relationship between low mood and ‘challenging’ behaviour has long been recognized in intellectual disability, where communication is sig-nificantly impaired (Hayes, McGuire, O’Neill, Oliver, & Morrison, 2011). Challenging behaviour occurs in 10–20% of people with ASDs, affects the entire intellectual ability spectrum (Emerson et al., 2001), but its causes are less well-understood than in those with intellectual disability without ASD. One possi-bility is that unrecognized mood problems partially explain high rates of challenging behaviour in ASD.

In the present study, we use data collected from the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP) cohort (Baird et al., 2006) at age 16 years to create a measure of SMP. We test whether the psychiatric, family and neurocognitive correlates to this scale are

similar in our ASD sample to those seen in typically developing populations.

Methods

ParticipantsThe sample in the present analyses comprises ninety-one 16-year olds with ASD from the 158 participants with ASD in the original SNAP cohort. In addition, longitudinal data from 12 years were available on 79 of the 91 individuals. As described previously [see Baird et al., (2006) for details], SNAP was drawn from a total population cohort of 56,946 children. All those with a current clinical diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder (PDD,N= 255) or considered ‘at risk’ for being an undetected case by virtue of having a statement of Special Educational Needs (SEN; N= 1,515) were surveyed using the Social Communication Questionnaire [SCQ (Rutter, Bailey, & Lord, 2003)]. A diagnostic assessment of a stratified sample at 12 years (also 255 individuals) identified 158 young people with ASD. The follow-up assessment at 16 years focussed on the cognitive phenotype of ASD and therefore only those who had estimated IQs of ‡50 at 12 years were invited to

participate (Charman et al., 2011). From the SNAP database, 131 possible participants were identified on the basis of IQ; of these, 19 indicated they were not interested in participating, 11 could not be con-tracted and 1 indicated interest, but was not in-cluded before the end of the study leaving 100 adolescent participants, for whom 91 had data to provide an SMP score for these analyses.

For this cohort, consensus clinical ICD-10 ASD diagnoses at 12 years were made using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised [ADI-R (Le Couteur et al., 1989)] and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic [ADOS-G (Lord et al., 2000)] as well as IQ, language and adaptive behaviour measures. The 91 in the contemporaneous analyses included 83 male, 8 female; 48 met consensus criteria for child-hood autism and 43 for another ASD. For the subset of 79 included in the longitudinal analyses, 73 were male and 41 had a diagnosis of autism. The sample had a mean age of 15 years 6 months (SD=5 months; range 14 years 8 months–16 years, 9 months) with a mean time interv al from the 12 year assessment of 4 years 0 months (SD=11 months, range 1 year 7 months–5 years 8 months).

The study was approved by the South East Research Ethics Committee (05/MRE01/67) and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

62-item questionnaire that assesses the severity and impact of 31 symptoms commonly reported in chil-dren and young people with neurodevelopmental disorders (Santosh, Baird, Pityaratstian, Tavare, & Gringras, 2006). For each symptom, a brief definition is given and the respondent is asked to endorse the overall frequency and impact on everyday life. Each component (frequency and impact) is each scored 0–5 (‘not at all’ to ‘all the time’/‘extremely’), with a com-bined score ranging from 0 to 10. Four items were included in the SMP scale, taking into consideration, the proposed DSM-5 criteria: ‘explosive range’, ‘low mood’, ‘depressive thoughts’ and ‘labile mood’. A description of the PONS, the presentation of the indi-vidual items and the means and ranges for the SNAP ASD samples are described in the supplementary online appendix and Supplementary Table S1. The scale had good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s aof .92. The raw scale was nonnormally distributed with a mean of 7.8 (SD 8.0, range 0–36) and a square-root transformation was applied to generate a more normally distributed continuous measure with skewness of 0.16 and kurtosis 2.78. A binary classi-fication divided the top 25% of scores (13–36,N= 24) from the rest of the distribution (0–12,N= 67). This threshold was chosen pragmatically because (a) it was likely to have reasonable power to detect mean dif-ferences and (b) it is conservative compared to the rates of ADHD (28%) and anxiety disorders (42%) re-ported in this cohort and is therefore, a plausible threshold to select.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ (Goodman, Ford, Simmons, Gatward, & Meltzer, 2000)], rated by parents at 12 and 16 years and teachers at 12 years, was also used to measure mental health symptoms. The SDQ is a widely used screening instrument for child psychiatric problems and its psychometric properties have been estab-lished in several samples, including UK (Goodman et al., 2000) and US studies (Bourdon, Goodman, Rae, Simpson, & Koretz, 2005). The present analyses use the hyperactivity, conduct and emotional sub-scales.

At 12 years, the parent-reported Child and Ado-lescent Psychiatric Assessment [CAPA (Angold & Costello, 2000)] was completed on 69 of the present sample. The CAPA is a semistructured psychiatric interview and the following diagnostic areas were included: all anxiety and phobic disorders (including obsessive-compulsive disorder); major depression and dysthymic disorder; ODD and conduct disorder (CD); ADHD; tics/Tourette/trichotillomania; enure-sis and encopreenure-sis. The prevalence rates and diag-nostic correlates have been reported previously (Simonoff et al., 2008).

Autism severity was assessed in three ways. We used the diagnostic dichotomy of childhood autism/ other PDD. Clinicians undertaking the review of autism diagnostic information based on the ADI-R and ADOS-G described above scored the 12 ICD-10

symptoms that comprise the autism spectrum dis-order diagnoses. The Social Responsiveness Scale [SRS (Constantino et al., 2003)] T scores were used as a quantitative measure of autism severity, scored at 12 years in 60 participants and at 16 years in 27, where data were missing at 12 years.

Adaptive functioning at 12 years was measured using the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales com-posite score (Sparrow, Balla, & Cichetti, 1984). A quantitative measure of the shortfall, or adaptive ‘under-function’, was generated by subtracting the Vineland score from the full-scale IQ, both measured at 12 years and standardized to mean of 100,SD15 and.

Maternal self-reports on the General Health Questionnaire [GHQ-30 (Goldberg & Muller, 1988)] when the participants were 12 and 16 years pro-vided a measure of maternal psychiatric symptoms with particular emphasis on mood, anxiety and so-matic difficulties. The Parenting Stress Index [PSI Short Form; (Abidin, 1995)] measures difficulties in the parent-child relationship on three subscales: disturbed child, parental distress and parent-child dysfunctional interaction. Parental distress was used, herein, to index the parental component of stress, as it attempts to measure parental charac-teristics rather than aspects of the parent-child relationship, which may be affected by the presence of an ASD in the child.

Neurocognitive measures. IQ was measured at 12 years with the Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children-Third Edition [WISC-IIIUK (Wechsler, 1992)] and at 16 years with the Wechsler Abbrevi-ated Scales of Intelligence [WASI (Wechsler, 1999)]. Details of the neurocognitive tasks are given in the Supplementary online appendix. All were adminis-tered at 16 years. The emotion recognition task has been previously described (Jones et al., 2011). In the present analysis, we used the Ekman-Friesen test of affect recognition (Ekman & Friesen, 1976), as this was most similar to tasks undertaken in typically developing youths with SMD (Brotman et al., 2008). We measured total number of correct responses.

The Card Sort was included as a measure of cog-nitive flexibility and response reversal (Tregay, Gil-mour, & Charman, 2009). The task requires the participant to correctly sort cards to one of three alternative sets across three trials, with the correct set varying in each trial. The key variable was the number of sorts required to reach criterion. In the present analyses, we included only those partici-pants who demonstrated an understanding of the rule in the first trial by reaching criterion before the end. The number of sorts required in the second and third trials was divided into four levels: top half (scores 12–18,N= 42); third quartile (scores 19–24,

Trail Making was included as a measure of atten-tional switching and response reversal. The task was comprised of three separate trials (Reitan & Wolfson, 1985). The participant was asked to ‘join the dots’ in numerical order, then, in a second trial, in alpha-betic order, followed by a third trial switching be-tween numbers and letters. The difference score between the time taken on the first and the third trial comprised a measure of switching ability. The mean difference score was 57.8 (SD 40.7, range 10.5– 229.1). As the data were highly skewed, a square-root transformed score was used in the present analyses.

Statistical analysis

Data reduction and statistical analysis were undertaken in Stata version 11 (StataCorp, 2009). Linear regression was used to examine the contin-uous outcome of the transformed SMP score and logistic regression for the binary variable of high versus low SMP scores. Ordinal logistic regression was used for the Card Sort, where a 4-level scale was generated, and for the analyses using the total number of psychiatric diagnoses on the CAPA. Multivariate regression, analogous to multiple analysis of variance, was employed to analyse the emotion recognition profile to allow for tests of an

overall effect and those specific to an emotion. Ordinal logistic regression was also used for ordinal outcomes, such as number of diagnoses. For sets of ordinal items, such as SDQ items, specificity of association was tested using similar models esti-mated in gllamm (www.gllamm.org) using a gener-alized estimating equations approach with an Independent Working Model. The models allowed separate threshold parameters for each item and estimated a common and an item-specific effect in the manner of testing for differential item function-ing. Significance of effects was determined from Wald tests using the robust form of the parameter covariance matrix.

Results

Participant characteristics, according to high/low SMP are shown in Table 1.

Emotional and behavioural characteristics associated with SMP

Examining the contemporaneous relationships be-tween the three parent-rated mental health problems domains of the SDQ (Table 2) revealed that hyper-activity, conduct and emotional problems all were associated with SMP in bivariate analyses, but that

Table 1 Sample characteristics according to severe mood dysregulation and problems (SMP) classification [M(SD)]

High SMP (N= 24) Low SMPa(N= 67)

Raw PONS scores on individual items

Explosive rage 4.9 (2.4) 1.2 (1.4)

Low mood 4.8 (2.3) 1.2 (1.4)

Labile mood 4.8 (2.8) 0.8 (1.6)

Depressive thoughts 4.6 (2.8) 0.6 (1.2)

Other characteristics at 16 years

Full-scale IQ 80.0 (16.6) 85.8 (17.5)

SDQcHyperactivity 6.6 (2.6) 5.7 (2.4)

SDQcConduct problems 2.6 (1.1) 1.5 (1.6)

SDQcEmotional problems 5.3 (2.1) 2.9 (2.3)

Maternal GHQ score 8.0 (8.5) 4.1 (6.3)

Other characteristics at 12 years

Adaptive behaviour 50.6 (12.3) 52.1 (14.4)

Diagnosed childhood autismN(%) 13 (54) 35 (52)

ICD-10 symptom severity 8.4 (2.4) 8.0 (2.5)

SRSb 101.3 (25.9) 90.3 (22.4)

SDQcHyperactivity (parent) 7.4 (2.8) 7.5 (2.5)

SDQcConduct problems (parent) 3.5 (1.9) 2.9 (2.1)

SDQ3Emotional problems (parent) 6.3 (2.5) 3.8 (2.4)

CAPA Any emotional problemN(%) 11 (57.9) 13 (26.0)

CAPA Oppositional defiant/conduct disorderN(%) 8 (42.1) 9 (18.0)

CAPA ADHDN(%) 8 (42.1) 9 (16.0)

Maternal GHQ score 7.3 (7.3) 4.9 (6.5)

Neurocognitive measures at 16

Ekman faces total score 41.8 (8.2) 42.8 (7.7)

Card sort errors to criterion 24.5 (8.3) 21.8 (8.7)

Trail making difference score 69.1 (48.8) 61.9 (43.7)

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CAPA, Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale.

aHigh SMP refers to those scoring in the top quartile, whereas low SMP is the rest of the distribution. bMeasured at 12 years in 60, at 16 years in 27.

only conduct and emotional problems remained significant in multivariate regression. The conduct problems scale includes amongst its five items ‘often has temper tantrums or hot tempers’, which is clo-sely related to the SMP concept; we hypothesized this item might underpin the association of SMP with conduct problems. Fitting an ordinal response model to the five SDQ conduct items showed a significant association with SMP (common proportional odds ratio (OR) 1.43, 95% CIs 1.23, 1.66; p< .001). However, the inclusion of an additional effect specific to tempers reduced the common partial OR to 1.18 (95% CIs 1.00, 1.40;p= .055), whereas the specific effect item was itself large and significant (OR = 2.09, 95% CIs 1.38, 3.16; p< .001). This provides concurrent validity for the concept of SMP as defined in the current study. Furthermore, al-though the emotional subscale of the SDQ includes items on anxiety as well as mood, this can also be considered an index of concurrent validity. To ad-dress the issue of whether the association with the SDQ emotional scale was simply due to overlapping item content, we repeated the regression with a truncated version of the SMP scale that included only explosive rage and labile mood. The results re-mained highly significant (b= .19, p< .001), indi-cating the relationship is due to co-occurrence of common mood and anxiety symptoms and those specifically related to severe mood dysregulation.

In examining the prediction of SMP at 16 years from mental health symptoms at 12 years, bivari-ate analyses showed the same pattern for parent and teacher ratings at 12 years; only SDQ emo-tional symptoms were significantly associated (Table 2); however, these effects were of moderate

size, with correlations for parent and teacher emotional scores at 12 and SMP of 0.44 and 0.18, respectively. These associations remained signifi-cant using the truncated SMP scale of explosive rage and labile mood (b = .16, p= .002; b= .20,

p= .001 for parent and teacher SDQ emotional scale respectively), indicating that common emo-tional symptoms predict to the less emoemo-tional components of SMD. Finally, in the subsample of 69, we used CAPA diagnoses at 12 years to predict the category of high (top quartile) SMP score. Having any CAPA emotional or behavioural disor-der at 12 years substantially increased the odds of being in the top quartile for SMP (OR = 9.6, 95%CIs 2.43, 37.00, p< .001), as did a diagnosis in each of the three domains: ADHD (OR = 3.82, 95%CIs 1.17, 12.47, p= .03.,); ODD/CD (OR = 3.32, 95%CIs 1.04, 10.59, p= .04); and any emo-tional (anxiety/depressive/phobic) disorder (OR = 3.92, 95%CIs 1.29, 11.86, p= .02). There were strong associations among the CAPA diagnoses and a multivariable analysis including all three CAPA domains as predictors of the high SMP category failed to distinguish an independent domain pre-dicting SMP 4 years later. However, ordinal logistic regression indicated a significant trend in the association between the number of the 12 possible CAPA disorders and being in the high SMP group (p value from ordinal logistic regression = .006). In relation to the high SMP category, rates were as follows: for no CAPA disorder, 3%, 95% CIs 0–19%; one CAPA disorder, 32%, 95% CIs 9–55%; ‡2

dis-orders 44%, 95% CIs 23–65%. The finding repli-cated when the CAPA diagnoses were collapsed to the three domains described above (ordinal logistic

Table 2 Personal characteristics under various scales associated with severe mood problems [95 per cent confidence intervals]

Unadjusted Adjusted

B(95% CIs) p b(95% CIs) p

Emotional and behavioural problems at 16 (parent-rated)

SDQ Hyperactivity .15 (.03, .28) .02 .03 ().08, .14) .56

SDQ Conduct problems .37 (.19, .56) <.001 .27 (.11, .44) <.01

SDQ Emotional problems .35 (.22, .45) <.001 .30 (.19, .41) <.001 Emotional and behavioural problems at 12 (parent-rated)

SDQ Hyperactivity .000 ().13, .13) .98

SDQ Conduct problems .14 ().03, .30) .10

SDQ Emotional problems .25 (.13, .36) <.001

Emotional and behavioural problems at 12 (teacher-rated)

SDQ Hyperactivity ).02 ().19, .13) .75

SDQ Conduct problems .11 ().08, .30) .27

SDQ Emotional problems .29 (.16, .42) <.001

Other personal characteristics

Full-scale IQ (current) ).01 ().03, .00) .13

Adaptive functioning (12 years) ).02 ().04, .01) .17 IQ-adaptive functioning discrepancy (12 years) .00 ().02, .02) .99 Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) Autism severity .02 (.01, .03) <.01 ICD-10 total autism symptom score .10 ().04, .23) .15 Maternal distress

Maternal GHQ, 16 years .07 (.02, .11) <.01

Maternal GHQ, 12 years .08 (.03, .13) .01

regression p< .001); the rate of high SMP category for one disorder domain 44%, 95% CIs 19–70%; ‡2 disorder domains 50%, 95% CIs 22–78%.

Other participant characteristics

Full-scale IQ, whether measured at 16 (Table 2) or 12 years (b= .01, 95%CIs).02, .01,p= .42) was not

associated with SMP. Similarly, neither adaptive functioning at 12 years nor the difference between cognitive ability and adaptive functioning was sig-nificantly associated with SMP.

Autism symptoms on the parent-reported SRS were strongly and positively related to SMP. In con-trast, the relationship was not replicated when using either the clinician-rated ICD-10 symptom score or the diagnostic classification of childhood autism/ other PDD. For the latter, the mean transformed SMP scores were 2.38 (childhood autism) versus 2.32 (other PDD),t= 0.20,p= .84).

Maternal mental health

Using maternal GHQ scores, we found a significant relationship between SMP and high scores at both ages. The latter relationship remained significant when the other contemporaneously assessed parental variables of educational and socioeconomic status and contextual factors of family-based and neighbourhood deprivation were included as cova-riates (b= .08, 95% CIs .02, .14,p= .01). To address the possibility that maternal mental health was indexing distress in relation to having a challenging child with ASD, rather than a characteristic of the mothers, we undertook a further regression in which we included as independent variables both the maternal GHQ score and the parental distress sub-scale from the Parenting Stress Index, both mea-sures at 12 years. The GHQ retained a similar level of prediction (b= .08, p= .002) as seen in the bivariate analysis (Table 2) while the index of parental distress was nonsignificant (b= .02,

p= .43).

Neurocognitive performance associated with SMP

Association with all emotions was tested using multivariate regression, which revealed a significant overall association between poorer emotion

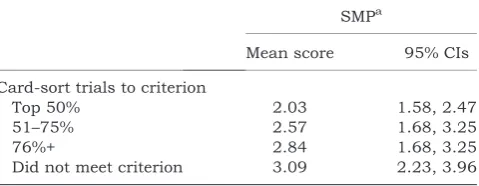

recogni-tion and SMP (F(6,86) = 3.00,p= .010), which post hoc tests identified as being due to a specific asso-ciation with surprise (Bonferroni corrected p= .04) (Table 3). Covarying for full-scale IQ and including only those 72 participants with IQ‡70 showed sim-ilar overall significant findings, but the Bonferroni-adjusted significance level is associated with sur-prise fell to 0.11 and 0.37 respectively. Results on the Card Sort using ordinal logistic regression, in which the three response categories were predicted by SMP, showed that SMP was associated with more errors or decreased cognitive flexibility (OR = 1.35, 95%CIs 1.04, 1.73, p= .02) (Table 4). However, the Card Sort trials to criterion were strongly associated with IQ (ordinal logistic regression OR = 0.91, 95% CIs 0.88, 0.94,p< .001), and when this was added as a covariate, the relationship between Card Sort trials and SMP became nonsignificant (OR = 1.24, 95% CIs 0.94, 1.63, p= .13). A sensitivity analysis limiting the participants to those with IQ ‡70 (N= 72) replicated the nonsignificant finding (p= .13).

In the Trail Making, there was no significant rela-tionship between transformed time difference score and SMP (b= .17, 95% CIs).17, .51,p= .33). IQ was

also strongly related to Trail Making (b= .07, 95% CIs ).10, ).04, p< .001), but its addition, as a

co-variate did not alter the pattern of results (p= .63), nor did the exclusion of participants with IQ <70 (p= .64).

Discussion and conclusions

This is the first examination of the mental health and neurocognitive correlates of SMP in adolescents

Table 3 Multivariate regression of association between severe mood problems and emotion recognition

Emotion Overall

testa

Happiness Sadness Rear Anger Surprise Disgust

F(6) p

B(95% CIs) p B(95% CIs) p B(95% CIs) p B(95% CIs) p B(95% CIs) p B(95% CIs) p

).09 ().21, 020) .11).01 ().31, .29) .96).15 ().54, .24) .45 .05 ().22, .32) .75).45 ().77,).13) <.01 18 ().22, .58) .37 3.00 .01

aBonferroni-corrected test of overall significance.

Table 4 Severe mood problems score according to Card sort trials to criterion

SMPa

Mean score 95% CIs

Card-sort trials to criterion

Top 50% 2.03 1.58, 2.47

51–75% 2.57 1.68, 3.25

76%+ 2.84 1.68, 3.25

Did not meet criterion 3.09 2.23, 3.96

SMP, severe mood problems.

with ASDs. The strongest mental health correlates are with emotional symptoms both in contempora-neous and predictive analyses. We considered the possibility that the SMP scale could be dominated by mood symptoms and therefore be not more than a proxy for emotional symptoms. However, all four symptoms contribute similar to the high SMP group and the scale has high internal consistency. Fur-thermore, the specific link to the ‘tempers’ item of the conduct scale adds additional support for the SMP construct in our sample. In addition, the association with the teacher emotional score at 12 years excludes the possibility of a parental rater bias. This finding is consistent with the literature in typically developing children showing that the lon-gitudinal course of SMP involves affective problems primarily (Brotman et al., 2006; Stringaris et al., 2009).

The relationship between SMP and ADHD has been previously identified, with a suggestion that emotional lability may be prominent in people with ADHD (Sobanski et al., 2010). Our findings in ASD do not provide a clear answer. SDQ ADHD symp-toms were neither predictive nor independently correlated with SMP. On the other hand, the pres-ence of any psychiatric disorder at age 12 was highly predictive of being in the top quartile for SMP at 16 (OR>9) and the prediction was equally strong for disorders in each of the three domains of emo-tional, oppositional/conduct and ADHD. Previously, we showed that, in this sample, more than 80% of those with ADHD also had an emotional and/or oppositional/CD (Simonoff et al., 2008), and this may be consistent with the SMP concept. However, it is interesting that a high SMP score at 16 is predicted not only by the presence of any disorder, but also by the number of individual diagnoses, further highlighting that there may be a number of different psychiatric correlates to SMP in people with ASD.

We found that autism severity, as measured on the parent-reported SRS was strongly associated with SMP, whereas the clinician-rated symptom score generated at 12 years was not. The SRS con-tains many more items with a wider range of scores than the other measures. The possibility of corre-lated measurement error in parents’ responses to the SRS and SMP scale cannot be excluded without another data source. Whatever the explanation for the discrepancy between parent- and clinician- re-ported autism severity scores and SMP, the finding that SMP are not associated with childhood autism versus another PDD is important for service provi-sion. As autism is generally considered more severe than Asperger syndrome or atypical autism/ ASDs, there is a temptation for clinicians to assume that all aspects of psychosocial functioning will be less impaired in the latter group. Our previous findings highlight that this diagnostic dichotomy does not predict the rate of co-occurring psychiatric

disorders (Simonoff et al., 2008) or the stability of psychiatric symptoms over time (Simonoff et al., 2012).

Neither full-scale IQ nor adaptive functioning was associated with SMP. This is consistent with previ-ous findings regarding co-occurring psychiatric dis-orders in SNAP (Simonoff et al., 2008) but it should be noted that other studies report a relationship between lower IQ and psychiatric problems in ASD (Totsika, Hastings, Emerson, Lancaster, & Berridge, 2011). Our prediction of an association between adaptive under-function and SMP was also not substantiated, excluding this as one reason for the IQ-adaptive functioning discrepancy.

We replicate the finding in otherwise typically developing children with SMD that parents are at increased risk of affective disorder (Brotman et al., 2007) and show that this is independent of the possible confounders of family background, neigh-bourhood deprivation and parental distress associ-ated with having a challenging child with ASD. Families of individuals with ASDs have higher rates of affective disorder, both major depression and bipolar disorder, and the nature of this association is not fully understood (Bolton, Pickles, Murphy, & Rutter, 1998; Ingersoll, Meyer, & Becker, 2011). However, this relationship does not appear to be solely a consequence of stress induced by raising a child with ASD as some cases of affective disorder in parents commenced prior to the child’s birth and other instances of affective disorder occurred in second degree, and other relatives not directly in-volved in the care of the autistic child. The current analyses suggest a specific relationship between maternal affective symptoms and SMP in offspring

within the ASD group that warrants additional exploration with more detailed psychiatric mea-sures, as the GHQ is a nonspecific measure of psy-chiatric symptoms.

We find very little support for the same neuro-cognitive correlates of SMD in our ASD sample as are reported in typically developing youth, i.e. poorer performance on emotion recognition (Guyer et al., 2007) and response reversal tasks (Dickstein et al., 2007; Dickstein, Finger, Skup, et al., 2010). Previous analyses of the emotion recognition tasks in SNAP demonstrated that participants with ASD were not generally deficient in emotion recognition compared to controls of the same intellectual abil-ity, but rather had specific difficulties correctly identifying the emotion of surprise (Jones et al., 2011). We report an association of SMP to the same emotion, but not for a wider range of emotions, as described in typically developing populations with SMD.

and cognitive rigidity, as measured by increased trials to criterion after having learned one rule. However, this relationship disappeared when IQ was accounted for. The IQ range in SNAP is wide (50–119), making it particularly important to con-sider its role in the performance of all neurocognitive tasks. Trail Making, also tapping cognitive flexibility, showed no association with SMPs in our ASD sam-ple. Thus, we failed to replicate the neurocognitive findings from typically developing samples. Our findings on neurocognitive tasks raise the possibility that different brain mechanisms are involved in SMP in people with ASD.

This study has a number of strengths. The sample is population–based and carefully characterized with respect to both their autism and general cognitive features. The longitudinal nature of the sample allows us to examine predictors of SMP as well as correlates. Most importantly, the sample remains unusual in having been assessed with respect to a wide range of both behavioural characteristics and neurocognitive tasks. It is this feature that allowed us to explore the relationship of SMPs to neurocognitive performance in ASD. We have been conservative in our analytic approach, limiting these to the tasks (emotion recog-nition, cognitive flexibility) associated with SMD in typically developing children.

The limitations to this study are also important to note. The study was not originally designed to assess SMD and the bespoke measure used herein, while carefully constructed, is not presently standardized or validated. Therefore, our findings must be inter-preted with caution. Furthermore, although the concept of SMD is an evolving one, this measure may imperfectly characterize the current definition, as it does not explicitly include an item on irritability (because this was not included in the PONS). Due to the moderate sample size of SNAP and the lack of an identified cut-off for the SMP score, most of the present analyses use the continuous measure in contrast with the findings reported in non-ASD samples, which study ‘clinical’ groups.

Despite these limitations, the results are interest-ing and important in showinterest-ing that SMP in adoles-cents with ASD represent a coherent and primarily

emotional construct. This is the first exploration of SMD in autism and the findings indicate that SMD is a psychometrically coherent concept in which psy-chiatric and family correlates are similar with those seen in typically developing children, but where the neurocognitive basis may be different. It will be important to test more definitively in larger samples that allow clinically meaningful subgroups whether these problems have similar or distinct origins. As SMD could be a target for intervention in ASD, future studies should also clarify its prevalence in ASD, its relationship to other measures of ‘challenging behaviour’ and the additional impairment that it causes, as well as investigating both the biological/ cognitive and environmental risk factors and corre-lates for SMD.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix S1 The Profile of Neuropsychiatric Symp-toms (PONS)

Appendix S2Details of neurocognitive tasks

Table S1Characteristics of individual PONS items for full ASD sample

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corre-sponding author for the article.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ellen Leibenluft for her advice on the item selection for the SMP scale and Paramala Santosh for permission to reprint the relevant items from the PONS.

Correspondence

Emily Simonoff, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, King’s College London, Institute of Psychi-atry and NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health, De Crespigny Park, London SE58AF, UK; Email: [email protected]

Key points

• Severe mood problems in young people are now considered a separate entity that predicts to subsequent

depressive disorder and has distinct neurocognitve and brain imaging correlates. • A new diagnostic category of severe mood dysregulation is proposed for DSM-5.

• Young people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have high rates of psychiatric comorbidities, but the role

of severe mood problems has not previously been studied.

• In adolescents with ASD, we found links to emotional and behavioural problems and family history similar to

those reported in otherwise typically developing youth, but did not see the same associations with the neurocognitive deficits in emotion recognition and response reversal.

References

Abidin, R.R. (1995).Parenting Stress Index(3rd edn). London: NFER: Nelson.

Angold, A., & Costello, E.J. (2000). The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry,39, 39–48. Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T.,

Meldrum, D., & Charman, T. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South East Thames – The Special Needs and Autism Project. The Lancet,368, 210–215.

Bakken, T.L., Helverschou, S.B., Eilertsen, D.E., Heggelund, T., Myrbakk, E., & Martinsen, H. (2010). Psychiatric disor-ders in adolescents and adults with autism and intellectual disability: A representative study in one county in Norway. Research in Developmental Disabilities,31, 1669–1677. Bolton, P.F., Pickles, A., Murphy, M., & Rutter, M. (1998).

Autism, affective and other psychiatric disorders: Patterns of familial aggregation.Psychological Medicine,28, 385–395. Bourdon, K.H., Goodman, R., Rae, D.S., Simpson, G., &

Koretz, D.S. (2005). The Strengths and Difficulties Ques-tionnaire: U.S. normative data and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry,44, 557–564.

Bradley, E., & Bolton, P. (2006). Episodic psychiatric disorders in teenagers with learning disabilities with and without autism.British Journal of Psychiatry,189, 361–366. Brotman, M.A., Guyer, A.E., Lawson, E.S., Horsey, S.E., Rich,

B.A., Dickstein, D.P., ... & Leibenluft E. (2008). Facial emotion labeling deficits in children and adolescents at risk for bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry,165, 385–389.

Brotman, M.A., Kassem, L., Reising, M.M., Guyer, A.E., Dickstein, D.P., Rich, B.A., ... & Leibenluft E. (2007). Parental diagnoses in youth with narrow phenotype bipolar disorder or severe mood dysregulation.American Journal of Psychiatry,164, 1238–1241.

Brotman, M.A., Rich, B.A., Guyer, A.E., Lunsford, J.R., Horsey, S.E., Reising, M.M., ... & Leibenluft E. (2010). Amygdala activation during emotion processing of neutral faces in children with severe mood dysregulation versus ADHD or bipolar disorder.American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 61–69.

Brotman, M.A., Schmajuk, M., Rich, B.A., Dickstein, D.P., Guyer, A.E., Costello, E.J., ... & Leibenluft E. (2006). Prevalence, clinical correlates, and longitudinal course of severe mood dysregulation in children.Biological Psychiatry, 60, 991–997.

Charman, T., Jones, C.R.G., Pickles, A., Simonoff, E., Baird, G., & Happe, F. (2011). Defining the cognitive phenotype of autism.Brain Research,1380, 10–21.

Constantino, J.N., Davis, S.A., Todd, R.D., Schindler, M.K., Gross, M.M., Brophy, S.L., .. & Reich W. (2003). Validation of a brief quantitative measure of autistic traits: Comparison of the social responsiveness scale with the autism diagnostic interview-revised.Journal of Autism & Developmental Disor-ders,33, 427–433.

Dickstein, D.P., Finger, E.C., Brotman, M.A., Rich, B.A., Pine, D.S., Blair, J.R. & Leibenluft E. (2010). Impaired probabi-listic reversal learning in youths with mood and anxiety disorders.Psychological Medicine,40, 1089–1100.

Dickstein, D.P., Finger, E.C., Skup, M., Pine, D.S., Blair, J.R., & Leibenluft, E. (2010). Altered neural function in pediatric bipolar disorder during reversal learning.Bipolar Disorders, 12, 707–719.

Dickstein, D.P., Nelson, E.E., McClure, E.B., Grimley, M.E., Knopf, L., Brotman, M.A., ... & Leibenluft E. (2007). Cognitive flexibility in phenotypes of pediatric bipolar disorder.Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry,46, 341–355.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W.V. (1976).Pictures of facial affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Emerson, E., Kiernan, C., Alborz, A., Reeves, D., Mason, H., Swarbrick, R., ... & Hatton C. (2001). The prevalence of challenging behaviors: A total population study.Research in Developmental Disabilities,22, 77–93.

Goldberg, D., & Muller, P. (1988).A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire GHQ. Windsor, England: NFER-Nelson. Goodman, R., Ford, T., Simmons, H., Gatward, R., & Meltzer, H. (2000). Using the Strengths and Difficulties Question-naire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample.British Journal of Psychiatry,177, 534– 539.

Guyer, A.E., McClure, E.B., Adler, A.D., Brotman, M.A., Rich, B.A., Kimes, A.S., ... & Leibenluft E. (2007). Specificity of facial expression labeling deficits in childhood psychopa-thology. [Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural].Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines,48, 863– 871.

Hayes, S., McGuire, B., O’Neill, M., Oliver, C., & Morrison, T. (2011). Low mood and challenging behaviour in people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research,55, 182–189.

Hutton, J., Goode, S., Murphy, M., Le Couteur, A., & Rutter, M. (2008). New-onset psychiatric disorder in individuals with autism.Autism,12, 373–390.

Ingersoll, B., Meyer, K., & Becker, M.W. (2011). Increased rates of depressed mood in mothers of children with ASD associ-ated with the presence of the broader autism phenotype. Autism Research,4, 143–148.

Jones, C.R., Pickles, A., Falcaro, M., Marsden, A.J., Happe, F., Scott, S.K., ... & Charman T. (2011). A multimodal approach to emotion recognition ability in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disci-plines,52, 275–285.

Joshi, G., Petty, C., Wozniak, J., Henin, A., Fried, R., Galdo, M., ... & Biederman J. (2010). The heavy burden of psychiatric comorbidity in youth with autism spectrum disorders: A large comparative study of a psychiatrically referred population. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders,40, 1361–1370.

Le Couteur, A., Rutter, M., Lord, C., Rios, P., Robertson, S., Holdgrafer, M., & McLennan J. (1989). Autism diagnostic interview: A standardized investigator-based instrument. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19, 363– 387.

Leibenluft, E. (2011). Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. American Journal of Psychiatry,168, 129–142.

Leibenluft, E., Cohen, P., Gorrindo, T., Brook, J.S., & Pine, D.S. (2006). Chronic versus episodic irritability in youth: A community-based, longitudinal study of clinical and diag-nostic associations.Journal of Child & Adolescent Psycho-pharmacology,16, 456–466.

Leyfer, O.T., Folstein, S.E., Bacalman, S., Davis, N.O., Dinh, E., Morgan, J., ... & Lainhart JE. (2006). Comorbid psychi-atric disorders in children with autism: Interview develop-ment and rates of disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,36, 849–861.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E.H., Leventhal, B.L., DiLavore, P.C., ... & Rutter M. (2000). The Autism Diagnos-tic Observation Schedule-Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism.Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,30, 205–223.

Munesue, T., Ono, Y., Mutoh, K., Shimoda, K., Nakatani, H., & Kikuchi, M. (2008). High prevalence of bipolar disorder comorbidity in adolescents and young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: A preliminary study of 44 outpatients. [Comparative Study].Journal of Affective Disorders,111, 170–175.

Reitan, R.M., & Wolfson, D. (1985). The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical interpre-tation. Tucson: Neuropsychology Press.

Rich, B.A., Carver, F.W., Holroyd, T., Rosen, H.R., Mendoza, J.K., Cornwell, B.R., ... & Lainhart JE. (2011). Different neural pathways to negative affect in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation.Journal of Psychiatric Research,45, 1283–1294.

Rutter, M., Bailey, A., & Lord, C. (2003).The Social Commu-nication Questionnaire (1st edn). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Santosh, P.J., Baird, G., Pityaratstian, N., Tavare, E., & Gringras, P. (2006). Impact of comorbid autism spectrum disorders on stimulant response in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A retrospective and prospec-tive effecprospec-tiveness study.Child: Care, Health & Development, 32, 575–583.

Simonoff, E., Jones, C., Baird, G., Pickles, A., Happe, F., & Charman, T. (2012). The persistence and stability of psy-chiatric problems in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. Advance online publication; doi: [JCPP-2012-00232.R2] Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas,

T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity and associated factors.Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,47, 921–929.

Sobanski, E., Banaschewski, T., Asherson, P., Buitelaar, J., Chen, W., Franke, B., ... & Faraone S.V. (2010). Emotional lability in children and adolescents with attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Clinical correlates and famil-ial prevalence.Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines,51, 915–923.

Sparrow, S., Balla, D., & Cichetti, D. (1984).Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circle Pines, Minnesota: American Guid-ance Services.

StataCorp (2009). Stata statistical software release 11.1. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation.

Stringaris, A., Cohen, P., Pine, D.S., & Leibenluft, E. (2009). Adult outcomes of youth irritability: A 20-year prospective community-based study. [Comparative Study]. American Journal of Psychiatry,166, 1048–1054.

Totsika, V., Hastings, R.P., Emerson, E., Lancaster, G.A., & Berridge, D.M. (2011). A population-based investigation of behavioural and emotional problems and maternal mental health: Associations with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability.Journal of Child Psychology & Psychi-atry,52, 91–99.

Tregay, J., Gilmour, J., & Charman, T. (2009). Childhood rituals and executive functions.British Journal of Develop-mental Psychology,27, 283–296.

Wechsler, D. (1992). The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for children(3rd edn). London: Psychological Corporation. Wechsler, D. (1999).Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence

(WASI). London: The Psychological Corporation.

![Table 1 Sample characteristics according to severe mood dysregulation and problems (SMP) classification [M (SD)]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/326564.113745/4.595.43.553.441.737/table-sample-characteristics-according-severe-dysregulation-problems-classication.webp)

![Table 2 Personal characteristics under various scales associated with severe mood problems [95 per cent confidence intervals]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/326564.113745/5.595.41.551.89.343/table-personal-characteristics-various-associated-problems-condence-intervals.webp)