ENGLISH: A STUDY OF PRAGMATIC TRANSFER

by:

Adea Fitriana

NIM: 1110026000046

ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT LETTERS AND HUMANITIES FACULTY

STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA

i ABSTRACT

Adea Fitriana. Expressions of Gratitude by Native Speakers of American English and Indonesian Learners of English: A Study of Pragmatic Transfer. Thesis. English Letters Department, Letters and Humanities Faculty, State Islamic University (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah, 2015.

The present study deals with comparing expressions of gratitude which are made by native speakers of American English and Indonesian by pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic approaches; and investigating the evidence of pragmatic transfer in the expressions of gratitude which are made by advanced Indonesian learners of English who have lived in the United States for at least 1 year. The objectives of the present study is to analyze how native speakers of American English and Indonesian compare in their expressions of gratitude by pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic approaches; and to examine whether there is evidence of pragmatic transfer in the expressions of gratitude which are made by Indonesian learners of English.

The participants in the present study are native speakers of American English and Indonesian and Indonesian learners of English. The data are collected by an 18-situations open-ended written Discourse Completion Task (DCT). In analyzing the data, qualitative method is employed. At first, expressions of gratitude which are made by three groups of participants are categorized into thanking taxonomy which is built by Cheng in 2005. Then, the expressions of gratitude in every situation are compared. After that, based on Gabriele Kasper‘s theory of pragmatic transfer, expressions of gratitude which are made by native speakers of American English and Indonesian are first compared by pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic approaches; and this baseline data is, then, used to investigate the evidence of pragmatic transfer in the expressions of gratitude which are made by Indonesian learners of English.

The present study finds three evidences of pragmatic transfer in the expressions of gratitude which are made by Indonesian learners of English: positive pragmalinguistic transfer in the use of thanking strategy; negative pragmalinguistic transfer in the use of alerter strategy; and negative sociopragmatic transfer in the use of alerter strategy. Similar perception between native speakers of American English and Indonesian on illocutionary force which

ii

APPROVEMENT

EXPRESSIONS OF GRATITUDE BY NATIVE SPEAKERS OF AMERICAN ENGLISH AND INDONESIAN LEARNERS OF ENGLISH: A

STUDY OF PRAGMATIC TRANSFER

A Thesis

Submitted to Letters and Humanities Faculty

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Strata One (SI)

ADEA FITRIANA NIM: 1110026000046

APPROVED BY

Advisor I, Advisor II,

Dr. Frans Sayogie, S.H., M.H., M.Pd. Danti Pudjiati, S.Pd., M.M., M.Hum. NIP: 19700310 200003 1 002 NIP: 19731220 199903 2 004

ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT LETTERS AND HUMANITIES FACULTY

STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA

iii

LEGALIZATION

Name : Aida Soraya NIM : 1110026000081

Title : The Social Factors of Code-Mixing in Annisa Tour and Travel Agency's Ticketing Staff's Utterances

The thesis entitled above has been defended before the Letters and Humanities Faculty's Examination Committee on February 16th, 2015. It has already been accepted as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of strata one.

Jakarta, February 16th, 2015

Examination Committee

Signature Date

1. Drs.Saefudin, M.Pd (Chair Person) ____________ _______

NIP. 19640710 199303 1 006

2. Elve Oktafiyani, M.Hum (Secretary) ____________ _______

NIP. 19781003 200112 2 002

3. Dr. H. M. Farkhan, M.Pd (Advisor I) ____________ _______

NIP: 19650919 200003 1 002

4. Sholikhatus Sa'diyah, M.Pd (Advisor II) ____________ _______

NIP: 19750417 20050 1 2007

5. Hilmi, M. Hum (Examiner I) ___________ _____ _

NIP. 19760918 20080 1 1009

iv

DECLARATION

I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the any other degree or diploma of the university or the institute of the higher learning, except where due knowledge has been made in the text.

Jakarta, May 28th 2015

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

In The Name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful

All praises to Allah, the Almighty and the one who gives us everything we cannot count. Praise to Him for this life, His mercy, guiding and blessing. Then, Shalawat and Salam are with our beloved prophet Muhammad SAW who has guided us from the darkness to the lightness.

The present study is presented to English Letters Department of Letters and Humanities Faculty, State Islamic University (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of strata one (S1). This work never be completed without a great deal of help from many people, especially Mr. Dr. Frans Sayogie, S.H., M.H., M. Pd. and Mrs. Danti Pudjiati, S. Pd., M.M., M. Hum as the writer‘s research advisors. Without their advices, support, encouragement and patience, this research is never completed.

I also would like to express the deepest gratitude to those who helped me to finish this research, namely:

1. Dr. Syukron Kamil, MA. The Dean of Adab and Humanities Faculty. 2. Drs. Saefudin, M. Pd. The Head of English Letters Department.

3. Mrs. Elve Oktafiyani, M. Hum. The Secretary of English Letters Department.

4. All lecturers in English Letters Department for teaching and educating the writer.

5. The writer‘s parents, Darmawan Oemar and Linda Bakri. Throughout the

vi

always there to encourage and support every step of the way, as they always do, with open-minded insight and love.

6. Berry Chandra and Mia Destriana as the writer‘s brother and sister who are always there to care and support the writer.

7. The writer‘s best friend Rajif Amar Kahfi. Thank to him for his time and untiring effort to help the writer to finish her undergraduate thesis. He is the best partner and closest advisor that the writer could imagine.

8. The writer‘s best friend Aida Soraya. Thank to her for appreciating, criticizing and supporting every step that the writer made.

9. The writer‘s best friends Siti Aisyah, Fadilah Mahmudah, Dian Agustina, Febrina Muslimawati, Lila Kusumayanti, Maya Yulindhini, Elena Soraya, Nurul Jannah, Rizka Yuniarsih, Fini Rubiyanti, and Benita Nurul Adzani. 10. The writer‘s organizational mates in Unit Kegiatan Mahasiswa (UKM)

Lembaga Pers Mahasiswa (LPM) Institut.

11.Mark Reppert. The deepest gratitude also goes to him for helping the writer to find native speakers of American English in the US who want to become participants of the present study.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... i

APPROVEMENT ... ii

LEGALIZATION ... iii

DECLARATION ... iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENT ... v

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... ix

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION ... 1

A. Background of The Study ... 1

B. Focus of The Study ... 3

C. Research Questions ... 3

D. Objectives of The Study ... 4

E. Significances of The Study ... 4

F. Research Methodology... 5

1. Method of the Study ... 5

2. Instrument of The Study... 5

3. Participants of The study ... 6

viii

CHAPTER II THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 8

A. Previous Studies ... 8

B. Pragmatic Transfer in Interlanguage Pragmatic ... 12

C. Speech Act of Thanking ... 23

D. Rationale of Using Open-Ended DCT ... 33

CHAPTER III DATA ANALYSIS ... 52

A.Categorization of Expressions of Gratitude ... 52

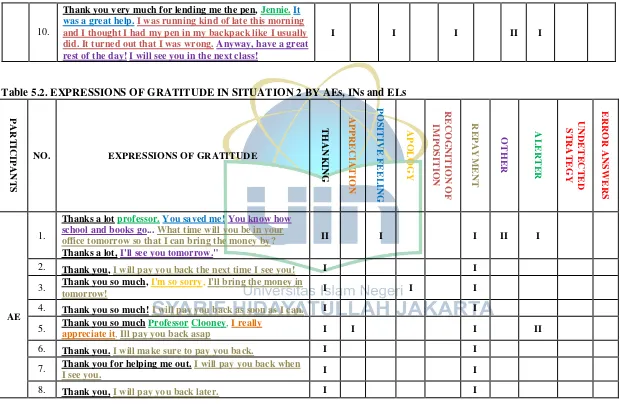

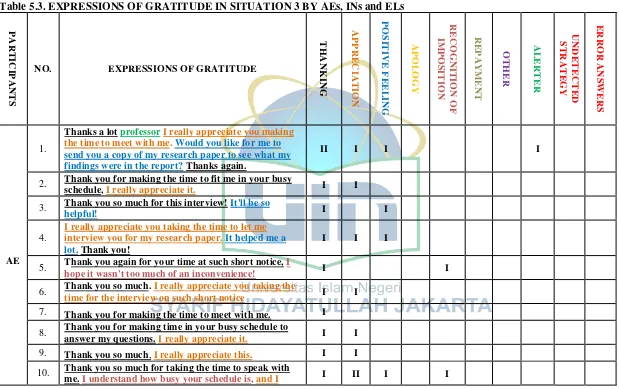

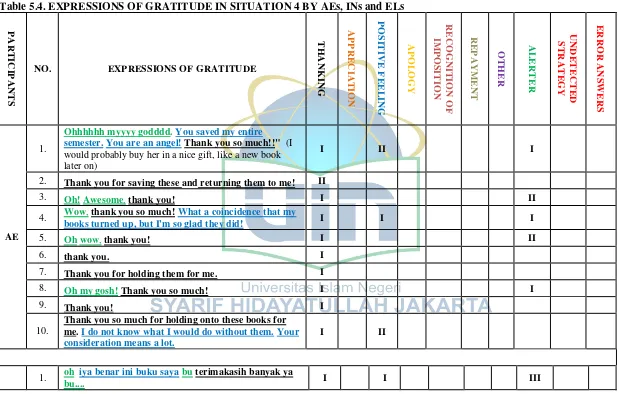

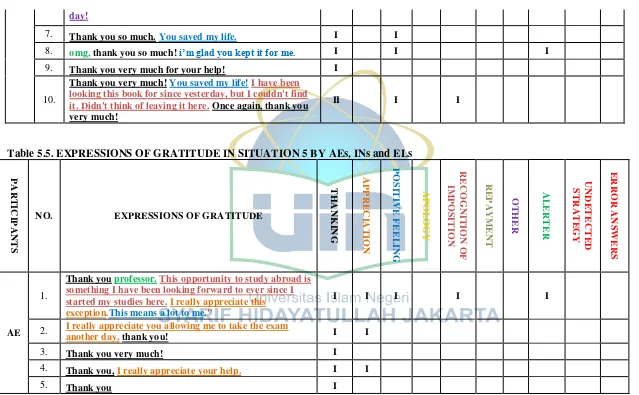

B. Comparison of Expressions of Gratitude by Situations ... 64

C.Comparison of Expressions of Gratitude by Native Speakers of American English and Indonesian by Pragmalinguistic and Sociopragmatic Approaches ... 82

D.Evidence(s) of Pragmatic Transfer in Expressions of Gratitude by Indonesian Learners of English ... 100

CHAPTER IV CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS ... 112

A. Conclusions ... 112

ix

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AE Native speaker of American English who become participant of the present study

DCT Discourse Completion Task

EL Indonesian learner of English who become participant of the present study

ESL English as a Second Language

IN Native speaker of Indonesian who become participant of the present study

L1 First language

L2 Second/foreign language NNS Non-Native Speaker NS Native Speaker SL Second Language

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

A.Background of the Study

Expressing gratitude is a universal language function; but, specific rules— on when, how, and to whom it should be appropriately expressed—are entirely culture-specific.1 Therefore, lack of awareness on cultural relativity which exists in the specific rules of expressing gratitude potentially brings language learners transferring their L1-based cultural notions when they express gratitude in L2 contexts since believing that their L1 norms are universal. Dogancay-Aktuna and Kamisli stated that having an assumption which pretends that speech behavior is universal may cause learners apply their L1-based norms into L2 contexts 2

The phenomenon of learners‘ applying their L1-based pragmatic knowledge

into their performance in L2 is discussed scientifically within the field of pragmatic transfer. According to Kasper, pragmatic transfer refers to an influence

which is resulted from learners‘ applying their pragmatic knowledge on how to

realize speech acts in L1 or any language and culture which have been acquired other than L2 when they comprehend, produce or learn L2 pragmatic information.3 Pragmatic transfer potentially occurs in the expressions of gratitude

1

Stephanie Weijung Cheng. ―An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study of Interlanguage Pragmatic Development of Expressions of Gratitude by Chinese Learners of English.‖ PhD diss., (University of Iowa: Iowa Research online http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/104 , 2005), p. 16.

2

Seran Dogancay-Aktuna and Sibel Kamisli, ―Pragmatic Transfer in Interlanguage Development: A Case Study of Advanced EFL learners.‖ Document Resume., (United States of America: Educational Resources Information center, 1997), p. 13.

3Gabriele Kasper, ―Pragmatic Transfer,‖ Second Language Research

which are made by language learners. It happens since, according to Hinkel, one‘s ability to express L2 thanking words completely does not ensure that he/she is able to know when and how gratitude should be appropriately expressed based on the rules of politeness in the L2 contexts.4

Eisenstein and Bodman revealed that advanced Japanese ESL learners who had lived in the US for years still negatively transferred their L1 norms when conversing in American English as their L2. When asked to say gratitude over their new boss‘ offer of salary increase, Americans mostly take reticence as, according to them, appropriate way to show modesty in preventing over grateful in front of someone who is not familiar to them.5 But, in similar situation, Japanese learners of English prefer to say length expression of gratitude. One

Japanese participant expresses: ―I'm sorry. I will try harder in the future‖.6 In

Japanese culture, expressing sumimasen which equals to I am sorry is eventually an appropriate response to express gratitude over unexpected favor.7

This phenomenon proves that Japanese learner of English inappropriately transfers their L1-based perception on how to express gratitude appropriately to someone who has low-familiarity when expressing gratitude in L2 context. The explanation above shows that pragmatic transfer potentially occurs in language

4Eli Hinkel, ―Pragmatics of Interaction: Expressing Thanks in a Second Language,‖

Applied

Language Learning, vol. 5, no.1. Document Resume., (United States of America: Educational

Resources Information center, 1992), p. 2.

5Miriam Eisenstein and Jean W. Bodman, ―I Very Appreciate‖

: Expressions of Gratitude by Native and Non-Native Speakers of American English, Applied Linguistics, vol. 7, no. 2 (Oxford University Press, 1986), pp 171-172.

6

Miriam Eisenstein and Jean Bodman. ―Expressing Gratitude in American English,‖ in Gabriele Kasper and Shosana Blum-Kulka., editors, Interlanguage Pragmatics. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 74.

7

learners‘ expressions of gratitude in L2 contexts. But, unfortunately, expressing

gratitude is one of the most infrequently studied speech acts in interlanguage pragmatics, in particularly within the field of pragmatic transfer.8

Noticing this fact, through the present study, the evidence(s) of pragmatic transfer in the expressions of gratitude which are made by advanced Indonesian learners of English who has lived in the US for at least one year is investigated. As the baseline data, the expressions of gratitude which are made by native speakers of American English and Indonesian is first compared by pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic approaches in order to discover similarity(s) and difference(s) which may potentially lead Indonesian learners of English to do pragmatic transfer, at pragmalinguistic or sociopragmatic level, when they express gratitude in the context of American English as L2.

B.Focus of the Study

The present study focuses on investigating the evidence(s) of pragmatic transfer in the expressions of gratitude as responses after receiving a favor which are made by advanced-level Indonesian learners of English who have lived in the US for at least a year.

C. Research Questions

According to the background of the study, the research questions which guide the study are as follow:

8

1. How are native speakers of American English and Indonesian compared in their expressions of gratitude as defined by pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic approaches?

2. What is the evidence of the pragmatic transfer in the expressions of gratitude which are made by Indonesian learners of English?

D. Objectives of the Study

The objectives of the study are:

1. To analyze how native speakers of American English and and Indonesian are compared in their expressions of gratitude by pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic approaches.

2. To examine what the evidence of the pragmatic transfer in the expressions of gratitude which are made by Indonesian learners of English is.

E. Significances of the Study

The writer hopes that the research will be:

1. Benefit in enriching research in pragmatic transfer on expressing gratitude. 2. Benefit in enriching an insight of cross-cultural comparison of expressing

gratitude by native speakers of American English and Indonesian.

required to recognize which their L1-based pragmalinguistic or sociopragmatic knowledge which is transferable to L2 contexts.

F. Research Methodology 1. Method

The data of the present study are expressions of gratitude which are made by native speakers of American English, native speakers of Indonesian and Indonesian learners of English. It is textual data which is elicited by DCT. Therefore, the qualitative method is used. As Dornyei stated, a study which uses qualitative method is a study which employs data collection procedures which elicit open-ended and non-numerical data; and, mainly uses non-statistical methods to analyze the data.9

2. Instrument of the Study

The instrument of the present study is DCT. There are English and Indonesian versions of the DCT. Native speakers of American English and Indonesian learners of English are given the DCT in English version, while native speakers of Indonesian are given the DCT in Indonesian version. In the present study, DCT has 18 open-ended situations which vary according to social status, ranking of imposition and familiarity. Almost all situations are adapted from some situations in DCTs which were previously distributed by Eisenstein and Bodman in 1986, Hinkel in 1992, and Cheng in 2005. In the DCT, before and after every

9

Zoltan Dornyei, Research Methods in Applied Linguistics: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed

participant is asked to respond every given situation, some questions which are related to the background information of every participant are provided.

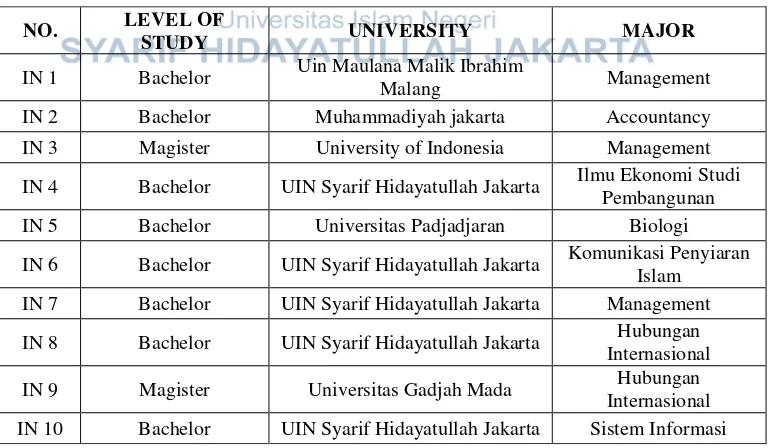

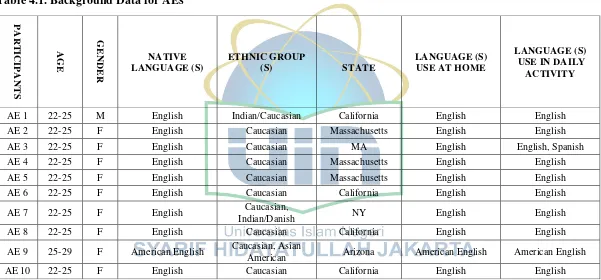

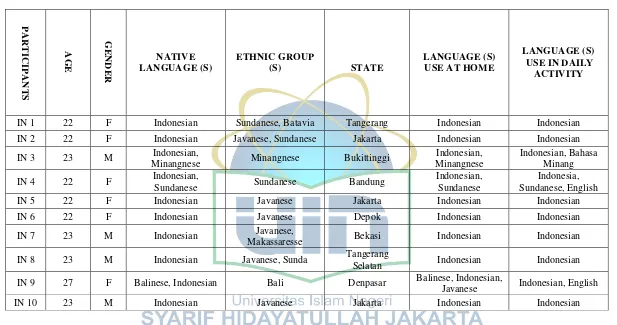

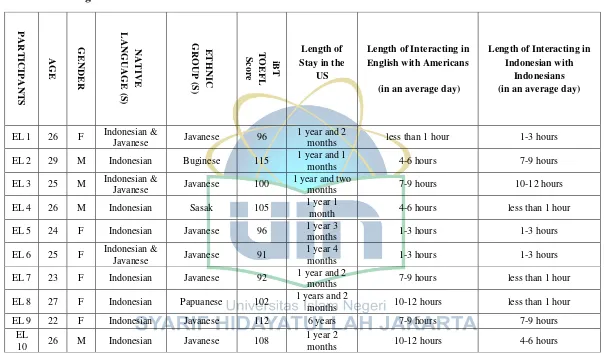

3. Participants of the Study

In the present study, a total of 30 participants are recruited. Participants are divided into three groups: AEs as the NSs of American English, INs as NSs of Indonesian and ELs as Indonesian learners of English. They are early-adult with 20-29 years old. In the present study, all situations in the DCT relate to university atmosphere. Hence, all recruited participants, at the time of data collection, are university students or graduated university students who are studying or studied in a university. 10 AEs are American-born university students and graduated university students who live in the US. Then, 10 INs are Indonesian-born university students or graduated university students who live in Indonesia. Every participant of both groups of NSs speaks his/her L1 at home and in daily activity. ELs have, at least, Indonesian as their L1. They are Indonesian born university students who have lived in the US for at least a year. They are categorized as advanced learners of English with, at least, 90 for iBT TOEFL score.

4. Data Analysis

(a) Expressions of gratitude which are made by AEs, INs, and ELs are first elicited by DCT which is employed as the instrument of the present study. (b) After the data is completely gathered, the expressions of gratitude which are

made by AEs, INs, and ELs are first categorized into thanking taxonomy which is built by Cheng in 2005.

(c) Then, expressions of gratitude which is made by AEs, INs, and ELs in every situation is compared.

(d) As the baseline data, expressions of gratitude which are made AEs and INs are first compared by pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic approaches. (e) In comparison to the baseline data, the evidence(s) of pragmatic transfer in

8

CHAPTER II

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

A.Previous Studies

Focusing on a cross-cultural comparison study in interlanguage pragmatics, in 1986, Eisenstein and Bodman investigated expressions of gratitude after receiving a gift, favor, reward, and service which are made by NSs and NNSs of American English.10 They employ a 14-situations open-ended DCT.11 They involve 56 NSs of American English and 67 advanced students in ESL classes at colleges in the US who come from 15 language backgrounds who living in the US for among 3 months until 9 years.12 By qualitatively analyzing, they report that NSs and NSSs have a noticeable pragmalinguistic difference in producing reciprocity strategy while expressing gratitude over a lunch treat.13

In 2005, developing an exploratory cross-sectional study of interlanguage pragmatic development, Cheng investigated effects of increase of lenght of stay in

the L2 community to learners‘ development of pragmatic competence by focusing

on expressions of gratitude after receiving a favor which are made by Chinese learners of English.14 She employs an 8-situations open-ended DCT.15 As the baseline data, she involves 64 NSs of Chinese who are graduate students at 7

10

Miriam Eisenstein and Jean W. Bodman (1986), op.cit, pp. 167-169. 11

Ibid. pp. 170, 179-180.

12

Ibid. p. 170.

13

Ibid. p. 175.

14

Stephanie Weijung Cheng (2005), op.cit. p. 1 . 15

universities in 4 cities in Taiwan and 35 NSs of American English who are graduate students at the University of Iowa.16

Then, Cheng investigates expressions of gratitude which are made by 53 advanced-level Chinese NNSs of American English with a minimum TOEFL score of 550 who have different lengths of stay in the US.17 By conducting descriptive and t-test analysis, the study finds an indication of pragmatic development through the length of stay in the US since expressions of gratitude which are made by Chinese NNSs who has lived in the US for more than 4 years and NSs of American English show no significant difference.18 Based on the expressions of gratitude which are made by NSs of American English and Chinese, Cheng builds a thanking taxonomy which is adopted in the present study.

Cheng‘s thanking taxonomy is adopted by some researchers. In 2009,

Maryam and Raja used it to categorize the expressions of gratitude which are made by 10 Iranian intermediate and advanced EFL learners, and NSs of Iranian and American English.19 Developing a cross-cultural comparison study in 2012,

Reza and Sima also used Cheng‘s thanking taxonomy to categorize expressions of

gratitude which are made by 180 Persian EFL students and 25 Chinese ESL learners.20 As the baseline data, they use the data of 35 NSs of American English

16

Ibid. pp. 30-31.

17

Ibid. pp. 27-28.

18

Ibid. pp. 1, 83.

19

Maryam Farnia and Raja Rozina Raja Suleiman, ―An Interlanguage Pragmatics Study of Expressions of Gratitude by Iranian EFL Learners – A Pilot Study,‖ Malaysian Journal of ELT

Research, Vol. 5. (Malaysia: Universiti Sains Malaysia, 2009), p. 121.

20

which was studied by Cheng.21 Reza and Sima reveal that Persian and Chinese learners use the same strategies as NSs of American English use in expressing gratitude, but preference of the strategies in certain contexts vary across cultures.22

Expressing gratitude is infrequently studied in the field of pragmatic transfer. Hence, in this section, studies of pragmatic transfer which focus on the other speech acts are explained to highlight the ways how the studies of pragmatic transfer are developed and what kind of study which is further needed. In 1993, by descriptively analyzing, Takahashi and Beebe found the evidence of pragmatic transfer in the corrections which are made by advanced-level Japanese ESL learners who live in the US.23 Developing a study of cross-linguistic influence, they compare corrections which are performed 15 Japanese ESL learners with 25 NSs of Japanese and 15 NSs of American English.24

As Kasper stated, Takahashi and Beebe use the term of cross-linguistic influence and pragmatic transfer interchangeably.25 Hence, their study is also categorized as a study of pragmatic transfer. In eliciting the data, they employ a 12-situations DCT.26 In 1997, Dogancay-Aktuna and Kamisli found the evidences of positive and negative transfer in the speech acts of chastisement which are performed by advanced-level Turkish EFL learners with TOEFL score of 500 and

21

Ibid. p. 119.

22

Ibid. p. 121.

23

Gabriele Kasper and Shosana Blum-Kulka, Interlanguage Pragmatics (New York: Oxford Universtity Press, 1993), p. 10.

24Tomoko Takahashi and Leslie M. Beebe, ―Cross

-Linguistic Influence in the Speech Act of Correction,‖ in Gabriele Kasper and Shosana Blum-Kulka (editors), Interlanguage Pragmatics, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 140.

25

Gabriele Kasper (1992), op.cit. p.206. 26

above who are all in two English universities in Turkey.27 They compare the speech acts of chastisement which are performed by 68 Turkish EFL learners with what are performed by 80 NSs of Turkish and 14 NSs of American English.28

Dogancay-Aktuna and Kamisli employ written role play consisted of 2 situations.29 By quantitatively analyzing, they find that similarities on the preference of between NNs of Turkish and American English lead Turkish EFL learners to do positive transfer, while differences between the performances of both groups of NSs lead Turkish EFL learners to do negative transfer when they perform the speech acts of chastisement in L2.30 In 2008, Wannaruk found evidences of pragmatic transfer in refusals which are made by 40 Thai EFL learners.31 As the baseline data, she first compares refusals which are made by 40 NSs of Thai and 40 NSs of American English.32 Developing a study of pragmatic transfer in 2009, Refnaldi revealed the evidences of pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic transfer in compliments which are made by 87 Indonesian EFL students in State University of Padang in Indonesia.33

Based on gathered previous studies, expressing gratitude was investigated in cross-cultural comparison and pragmatic development. But, there is no study on expressing gratitude in the field of pragmatic transfer which is found. More studies are called to investigate the speech act of expressing gratitude in pragmatic

27

Seran Dogancay-Aktuna and Sibel Kamisli (1987), op.cit. pp. 4, 13. 28

Anchalee Wannaruk, ―Pragmatic Transfer in Thai EFL Refusals,‖RELC Journal, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Sage Publications, 2008), pp. 330-332.

32

Ibid. p. 320.

transfer. Then, there is only one study which is found which investigates the evidence of pragmatic transfer based on the types of pragmatic transfer: pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic. Hence, more studies which specifically investigate pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic transfer are needed. Then, studies which report detailed explanation on how NSs of Indonesian or Indonesian learners of English express gratitude are not found. Thus, studies on Indonesians and Indonesian learners of English in expressing gratitude are needed.

B.Pragmatic Transfer in Interlanguage Pragmatics

Pragmatic transfer is a domain of Interlanguage Pragmatics (ILP).34 As a branch of interlanguage studies, ILP is one of the other branches such as interlanguage phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics.35 As a part of pragmatics, ‗pragmatics‘ in ILP is the study of people‘s comprehension and production of linguistic action in context.36 ILP was categorized as a part of SLA research, but, primary studies on ILP makes the position of ILP as a branch of SLA becames debatable. Emergence of studies on pragmatic transfer in ILP is one factor which makes ILP no longer compatible to be a part of SLA research. Since studies on pragmatic transfer in ILP primarily focus on locating the evidence of pragmatic transfer, knowing the conditions which cause the occurrence of pragmatic transfer, and relating the occurrence of pragmatic transfer with structural and non-structural factors, according to Kasper, pragmatic transfer makes the position of ILP is more compatible to mainstream SL research which

34

Gabriele Kasper and Shosana Blum Kulka (1993), op.cit. p. 10. 35

Ibid. p. 3.

36

primarily focus on how NNSs comprehend and produce speech acts rather than SLA research which mainly focus on how NNSs acquire L2 knowledge.37

1. Definition of Pragmatic Transfer

Pragmaticists have different perspectives on defining the scope of

‗pragmatics‘ in pragmatic transfer. According to Zegarac and Pennington,

pragmatic transfer refers to a situation in which learners transfer their L1 pragmatic knowledge when conversing in intercultural communication.38 Cheng argues that pragmatic transfer refers to a condition in which learners use their L1 rules of speaking when speaking in L2.39 Similar to Cheng, Ahmed states that pragmatic transfer occurs when language learners use the rules of speaking of L1 community while they interact or speak in L2.40 The proposed definitions reflect that the scope of ‗pragmatics‘ in pragmatic transfer can be defined as pragmatic knowledge and rules of speaking of L1 culture.

But, there is no pragmaticist who explicitly clarifies further explanation on what type of rules of speaking or pragmatic knowledge which is specifically

studied under the term ‗pragmatic transfer‘. Kasper proposes that patterns of

speech act realization are the scope of pragmatic in pragmatic transfer as what are

called ‗rules of speaking‘.41

Kasper defines pragmatic transfer as an influence

37

Gabriele Kasper (1992), op.cit,. pp. 203-205.

38Vladimir Zegarac and Martha C. Pennington, ―Pragmatic Transfer‖ in Spancer

-Oatey, Helen., editor, Culturally Speaking: Culture, Communication and Politeness Theory (New York: Continuum, 2000), p. 143.

39

Stephanie Weijung Cheng (2005), op.cit., p. 22. 40

Ahmed Qadoury Abed, ―Pragmatic Transfer in Iraqi EFL Learners‘ Refusals,‖ International

Journal of English Linguistics, Vol 1, No. 2 (Canadian Center of Science and Education, 2011) , p.

167. 41

which is resulted from learners‘ applying their pragmatic knowledge on how to

realize speech acts in languages and cultures which have been acquired other than L2 when they comprehend, produce or learn L2 pragmatic information.42

Any language(s)—other than L1—which has been acquired potentially

influence learners‘ performance in L2. As Odlin stated, transfer occurs as a result

from the existence of the similarities and differences between language(s) having been acquired and L2.43 But, the evidences of pragmatic transfer are frequently investigated by only comparing communicative behavior of NSs of L1 and L2

with learners‘ interlanguage data. Zegarac and Pennington also argue that

comparing communicative behavior of learners with the communicative behavior of NSs of L1 and L2 is a method which supports the investigation of the occurrences of pragmatic transfer.44

Observing into many interlanguage pragmatic studies, Kasper argues that many pragmaticists have made random claims on the evidences of pragmatic transfer since they underlie their identification on informal estimation of the percentages of the use of particular category (semantic formula, strategy, or linguistic form) occurs in L1, L2 and interlanguage data of the NNSs.45Hence, in

preventing random claims, by adapting Selinker‘s definition of language transfer,

Kasper proposes that an ideal method in identifying evidence of pragmatic

transfer is by seeking a statistically significant trend of NSs of learners‘ L1 toward

42

Ibid. p. 207.

43

Terence Odlin, Language Transfer, (Cambridge: Cambridge Universtity Press, 1989), p. 27. 44

Vladimir Zegarac and Martha C. Pennington (2000), op.cit. p.144. 45

one of the alternatives which is then paralleled by a significant trend of language learners toward the same alternative when they are in L2 context.46

Kasper does not clearly define what is meant by the case of a statistically significant trend toward one of the alternative. But, applying her definition, with Bergman, Kasper stated that evidence of pragmatic transfer is found where, more than half of NSs of Thai and Thai learners of English who respond to two contexts (student forgetting to return a book borrowed from professor; professor forgetting to grade a student's paper) similarly offered repair in their apologies.47 If it is looked in detail, there is one alternative of offering repair in apologizing both from student to professor and professor to student, regardless the assessment of social status of the interlocutors, which is significantly used by NSs of Thai since it is reflected by, in two unequal-status situations, there are more than half of NSs who offer repair in their apologies. It is then followed by Thai learners of English.

In short, a statistically significant trend to one of these alternatives refers to a condition in which one alternative is significantly used by NSs or language learners, reflected by, in every situation which structurally draws the alternative which is significantly chosen, a strategy is dominantly used by more than half of NSs or language learners. It is supported by the fact that it is negative pragmatic transfer because, while more than half of NSs of American English offered repair in their apologies in the context of student forgetting to return a book borrowed from professor, more than half of NSs of American English do not offer repair in

46

Ibid. p. 223.

47

their apologies in the context of professor forgetting to grade a student's paper.48 It

is clear that ‗a statistically significant trend toward one of the alternatives‘ is not

simply related to the used strategy, but it ties to the chosen alternative itself.

2. Types of Pragmatic Transfer

In 1992, Kasper developed and applied pragmalinguistics and sociopragmatics as methodological approaches in studying pragmatic transfer in interlanguage pragmatics.

a. Pragmalinguistic Transfer

The term ‗pragmalinguistics‘ is applied by Leech as a methodological approach which is studied under a paradigm of ‗General Pragmatics‘, a paradigm which he launched in 1983.49‗Pragmalinguistics‘ was also developed by Thomas in 1983 as a pragmatic analysis in studying pragmatic failure.50 In 1992, Kasper developed operational theory of pragmatic transfer, in which pragmalinguistic become a methodological approach in pragmatic transfer. According to Kasper,

‗pragmalinguistics‘ refers to either particular strategies which are used to convey

particular illocutions or variety of strategies which are chosen by the interlocutors to convey similar illocutionary act but they are vary in meaning or politeness.51

Although the term ‗pragmalinguistics‘ refers to strategies to convey illocutions, it does not mean that pragmalinguistic transfer in the field of

48

Ibid. pp. 212-213, 224.

49

Geoffrey Leech, Principles of Pragmatics¸ (London: Longman, 1983), pp. 10-11. 50

Jenny Thomas, ―Cross-Cultural Pragmatic Failure,‖ Applied Linguistics, vol. 4, vo. 2, (1983), p. 99.

51

pragmatic transfer can simply be defined as the tranfer of L1 strategies. Hence, Kasper criticizes Thomas‘s which restricts the notion of pragmalinguistic transfer into the transfer of speech act strategies and utterances. Explaning pragmalinguistic transfer is a factor which causes pragmalinguistic failure, Thomas argues that pragmalinguistics transfer refers to inappropriate transfer of speech act strategies or utterances:

… pragmalinguistics transfer‘ –the inappropriate transfer of speech act

strategies from one language to another, or the transferring from the mother tongue to the target language of utterances which are semantically and syntactically equivalent, but which, because of different 'interpretative bias', tend

to convey a different pragmatic force in the target language.52

Kasper stated that , in the field of pragmatic transfer, pragmalinguistic

transfer occurs when learners‘ perception and production of strategies to convey

illocutionary act in L2 is influenced by illocutionary force or politeness value which is assigned in linguistic materials such as speech act strategies or utterances in their L1.53Transferring the illocutionary force assigned in Russian‘s utterance

konesno to the production of of course in English is an example of pragmalinguistic transfer as a result of transferring illocutionary force assigned in an utterance of L1 that semantically equivalent but having different illocutionary force in L2:

A Is it a good restaurant?

B Of course. [Gloss (for Russian speaker)]: Yes (indeed) it is. (For English

hearer): What a stupid question!] 54

By semantical and syntactical point of view, there is nothing wrong with of course which is uttered by Russian speaker in a given example above. But, in

52

Jenny Thomas (1983), op.cit., p. 101. 53

Gabriele Kasper (1992), op.cit,. p. 209. 54

pragmatic point of view, of course which is uttered by Russian speaker has different illocutionary force for Russian as the speaker and English hearer. It happens since in Russian, konesno (or equal to of course in English) is used to convey enthusiastic affirmative (such as: yes, indeed, certainly), while in English

of course is used to answer a question about something which is eventually self-evident.55 Pragmalinguistic transfer as a result from transferring politeness value assigned in L1 strategies is found when Hebrew learners of English successfully transfer their L1 politeness value assigned in indirect strategy of request in expressing indirect request ‗Can you do X?‘ when conversing in English.56

As Wierzbicka stated, reflecting Anglo-Saxon culture which respects

everyone‘s privacy, accepts compromises and avoids in showing dogmatism,

English eventually has special non-universal grammatical devices in which the interrogative form, normally used for asking, can function to make an offer or to be indirect request for avoiding imperatives.57 Since Hebrew and English have grammatical device of interrogative form which is used to make indirect request, it can be concluded that those languages have similar politeness value to respect

everyone‘s privacy and etc which is assigned in the interrogative forms for

making indirect request which the languages provide.

55

Ibid. p. 101.

56

Shosana Blum-Kulka, ―Learning to Say What You Mean in a Second Language: A study of the Speech Act Performance of Learners of Hebrew as a Second Language,‖Applied Linguistics vol. 3, no. 1 (1983), p. 48.

57

Anna Wierzbicka, Cross-Cultural Pragmatics, The Semantics of Human Interaction, Second

b. Sociopragmatic Transfer

According to Leech, sociopragmatic is ‗the sociological interface of

pragmatics‘.58

In 1992, Kasper also applied sociopragmatics as a main locus and methodological approach of pragmatic transfer. According to Kasper,

‗sociopragmatics‘ refers to speakers‘ perception and perfomance of linguistic

action which is underlied by culturally based social perception.59 As quoted by Chang, Harlow states that sociopragmatic competence is an ability to ―vary speech-act strategies according to the situational or social variables in the act of

communication‖.60 Either pragmalinguistic or sociopramatic judgment eventually

has to be involved in an utterance in order to be pragmatically successful.61 But, in L2 use, different social perceptions which vary across cultures and languages may lead language learners to apply their L1 social perception in expressing linguistic action in L2 contexts. This condition, then, is called as sociopragmatic transfer. Kasper states that, in pragmatic transfer, sociopragmatic

transfer occurs when language learners‘ assessment which is equivalent to the

social perceptions in their L1 contexts underlies and influences their social perception in interpreting and performing linguistic action in L2.62

Eisenstein and Bodman report the occurrences of sociopragmatic transfer.63

In responding to new boss‘ offer of salary increase, NSs of American English

Yuh-Fah Chang,―Interlanguage Pragmatic Development: The relation between pragmalinguistic competence and sociopragmatic competence,‖Language Sciences, vol. 33, (Elsevier, 2011) p. 787. 61

Jenny Thomas (1983), loc.cit., pp. 103-104 62

Gabriele Kasper (1992), op.cit. pp. 209-210. 63

gratitude to their boss who eventually is situated to have large social distance and higher social power. 64 In contrast, in responding to similar situation, some Chinese and Japanese NNSs of English prefer to express some thanking strategies as appropriate ways in their cultures to say thanks to their boss over the offer of salary increase. One Chinese NNSs of English expresses gratitude by showing felling of undeserving the raise and promise to do self-improvement after using

thanking: ―Thank you very much. But I think I have not done so well to get a

raise. Anyway, I'd try to do better.‖65

3. Manifestations of Pragmatic Transfer

According to Kasper, in the notion of pragmatic transfer, the outcome of either pragmatic transfer may be congruent or incongruent with L2.66 Hence, she divides the manifestations of pragmatic transfer into positive and negative transfer.

a. Positive Transfer

Positive transfer is a kind of ‗facilitation‘ from L1 and L2 which have

similar language system; hence, the generalization of L1 pragmatic knowledge is successfully transferred in L2 context.67 Positive transfer occurs when the outcome of the transfer is positive, in which non-universal specific L1-based pragmalinguistic or sociopragmatics knowledge being projected into L2 matches

64

Miriam Eisenstein and Jean W. Bodman (1986), op.cit., 171 . 65

Miriam Eisenstein and Jean Bodman (1993), op.cit., 74. 66

Gabriele Kasper (1992), op.cit. 209. 67

to the pragmatic perceptions and behaviors of L2 contexts.68 Positive transfer occurs when the frequencies of a pragmatic feature are lack of statistically significant differences.69 Odlin states that, when the differences between L1 and L2 are few, language learners obtain an advantage since they potentially become successful when communicating in L2 context.70 Hence, positive transfer is able to lead learners to be successful in interacting in cross-cultural situation.

b. Negative Transfer

Negative transfer occurs when the outcome of the transfer is negative; L1-based pragmalinguistic or sociopragmatic knowledge which is transferred is incongruent with L2 pragmalinguistic or sociopragmatic knowledge.71 Negative transfer occurs when L1 and L2 do not have similar pragmatic knowledge, hence, applying L1 pragmatic knowledge into L2 contexts result failures.72 In Kasper and Blum-Kulka, Takahashi and Beebe, using descriptive method, find the evidence of pragmatic transfer in which one alternative of not using any positive remark to soften the correction which is made for everyone is significantly used by NSs of Japanese and then is paralleled by Japanese learners of English.

The evidence of pragmatic transfer which is mentioned above is evident by the fact that, in two given situations (a professor correcting a student for mentioning wrong date, and; student correcting a professor for mentioning wrong name of scholar), there are only less than half of NSs of Japanese and Japanese

68

Gabriele Kasper (1992), op.cit., p. 212. 69

Ibid. p. 223.

70

Terence Odlin (1989), op.cit., p.26. 71

Gabriele Kasper (1992), op.cit.,p. 213. 72

learners of English who use positive remark.73 It is negatively transferred since NSs of American English significantly use the other alternative of using positive remark in correcting to only someone who has lower-status level. It is evident by the fact that, in the situation in which professor correcting a student for mentioning wrong date, more than half of NSs of American English soften their corrections with using any positive remark, whereas there is no one who uses positive remark in the correction in the situation of student correcting the professor over mentioning wrong name of scholar.74

4. Developmental Aspects as Non-Structural Factors of Pragmatic Transfer Pragmatic transfer is widely investigated by doing contrastive analysis between interlanguage data of L2 learners in comparison with the data of NSs of L1 and L2 as responses toward some comparable contexts. But, not simply doing

such ‗structural‘ comparison, investigating the occurrences of transfer has to

involve non-structural factors which may potentially influence learners in recognizing which their L1 pragmatic knowledge is transferable into L2 contexts.75 Developmental aspects are non-structural factors which can be involved in analysis of pragmatic transfer. Developmental aspects focus on

learners‘ level of proficiency and learners‘ length of stay in L2 community as two

aspects which may affect the occurrences of pragmatic transfer since these aspects

influence learners‘ familiarity on L2 pragmatic knowledge.76

73

Tomoko Takahashi and Leslie M. Beebe (1993), op.cit. p.141-145. 74

Ibid. p.141-145.

75

Terence Odlin (1989), op.cit., p. 28. 76

As a developmental aspect in non-structural factors of pragmatic transfer,

learners‘ level proficiency relates to the occurrences of pragmatic transfer.

Learners with low-level proficiency are considered to make more numbers of pragmatic transfer, while learners with high level proficiency are considered to have the ability to classify which are transferable and not.77 However, noticing

that level of proficiency alone cannot assure learners‘ development of L2

pragmatic knowledge, Kasper proposes that length of stay in L2 community can be further examined as developmental aspect in the investigation of pragmatic transfer since it may increase learners‘ familiarity with L2 contexts.78

C.Speech Act of Thanking

The realization of speech acts is the scope of the term ‗pragmatics‘ in the

notion of pragmatic transfer which is proposed by Kasper. According to Austin,

speech acts are defined as ‗utterances that do things‘.79

Austin exemplifies that

uttering ‗I name this ship Queen Elizabeth‘ (when smashing the bottle) is an

instance of speech act in which the utterance is a part of doing an action of naming.80 By noting the example, speech acts are utterances which do not describe, report or state that someone is doing an action, but speech acts are utterances which become parts of doing actions.

Using the terms ‗illocutionary acts‘ and ‗speech acts‘ interchangeably, there

are five types of speech acts in Searle‘s conception:representatives, directives,

77

Ibid. pp. 219-220.

78

Gabriele Kasper (1992), op.cit. p. 220. 79J. L. Austin, ―How to do things with words,‖

in Dawn Archer and Peter Grundy., editors, The

Pragmatics Reader (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 19.

80

commissives, expressives and declarations.81 Searle argues that speech acts of thanking are categorized as expressive illocutionary acts which are made by speakers when they believe that the act doing by the hearers in the past is beneficial for the speakers.82 The taxonomy of illocutionary acts which are proposed by Searle is adopted in the present study.

By arguing that gratitude is expressed as response of some beneficial action which is done by another person, Coulmas proposes situations that require gratitude as the response: thanks ex ante (for a promise, offer, invitation); thanks ex post (for a favor, invitations (afterwards)); thanks for material goods (gifts, services); thanks of immaterial goods (wishes compliments, congratulations, information); thanks for some action initiated by the benefactor; thanks for some action resulting from a request/wish/order by the beneficiary; thanks that imply indebtedness; and thanks that do not imply indebtedness. 83

Gratitude is not simply expressed by stating the illocutionary verb ‗thank‘.

Most of NSs of American English tend to express speech acts sets or indirect

speech acts sets, like uttering the lack of necessity such as ‗Oh, you shouldn't have

…‘ , to express their gratitude.84

As Austin stated, all regular utterances are

‗performative‘, either the utterances consist of performative verbs (such as: I

promise that I shall be there) or do not consist of any performative verb (such as: I shall be there).85 It can be concluded that ‗Oh, you shouldn't have …‘ is

81

Stephanie Weijung Cheng (2005), op.cit. pp. 9-10 . 82

Miriam Eisenstein and Jean W. Bodman (1986), op.cit, pp.167-168. 83

Eli Hinkel (1992), op.cit. pp. 5-6. 84

Miriam Eisenstein and Jean W. Bodman (1993), op.cit., p.67. 85

categorized as performative utterance or speech act which is a part of doing action

of thanking even it does not contain any verb ‗thank‘.

Accomodating the expressions of gratitude which are made by NSs of American English and Chinese, Cheng builds a thanking taxonomy which is then adopted in the present study to categorize expressions of gratitude which are made

by AEs, INs and ELs. Cheng‘s thanking taxonomy is presented as follows86

: 1. Thanking

There are three subcategories which are classified as thanking strategy: a) by using the word thank

In this subcategory, people express thanking by only using the word ‗thank‘ in English, or any other words from the other languages that have similar meaning.87 The examples are88:

in English : thanks, thank you, thank you very much in Chinese : xièxiè (thank you)

b) by thanking and stating the favor

In this subcategory, besides simply expressing thanking with the word

‗thank‘ or any other words from the other languages which have similar

meaning, the favor being thanked is also mentioned.89 In English, the examples is: thank you for your help.90

c) by thanking and mentioning the imposition

86

Stephanie Weijung Cheng (2005), op.cit.pp. 40-49. 87

Ibid. p. 40. 88

Ibid. p. 41. 89

Ibid. p. 41. 90

In this subcategory, besides thanking, the imposition which is caused by the favor is also mentioned.91 The example is92:

in English : thank you so much for letting me borrow it those extra days

2. Appreciation

Appreciation has two subcategories:

a) by using the word appreciate without elaboration

In this subcategory, people express appreciation by using the word

‗appreciate‘ in English or any other words in other language which have

similar meaning with ‗appreciate‘ (such as: ganxìe in Chinese) without elaboration to another words.93 The examples are94:

in English : I greatly appreciate your help; I appreciate it

b) by using the word appreciate and mentioning imposition caused by the favor

In this subcategory, besides simply expressing appreciation by using the

word ‗appreciate‘ in English or any other words in other languages that have

similar meaning with ‗appreciate‘, the imposition reasoned by the favor being thanked is also mentioned.95 The example is96:

in English : I really appreciate your time and effort

91

Ibid. p. 41. 92

Ibid. p. 41. 93

Ibid. p. 42. 94

Ibid. p. 42. 95

Ibid. p. 42. 96

3. Positive feelings

Positive feelings strategy has three subcategories:

a) by expressing a positive reaction to the favor giver (hearer)

This kind of positive feeling is made when people express positive reaction or compliments to the favor giver (hearer).97 The examples are98:

in English : You are a life saver; I‘m so grateful for your help

b) by expressing a positive reaction to the object of the favor

This kind of positive feelings is made when people express positive reaction or compliment to the object of the favor. The examples are99:

in English : This book was really helpful; Your notes is very clear

c) by expressing a positive reaction to the outcome of the favor

This kind of positive feelings is made by expressing positive reaction the outcome or the result of the favor which the thank giver (speaker) will achieve in the future.100 The example is101:

in English : I'll keep you posted on what happens

4. Apology

Apology strategy has three subcategories:

a) by using only apologizing words (i.e., sorry or apologize)

97

Ibid. p. 43. 98

Ibid. p. 43. 99

Ibid. p. 43. 100

Ibid. p. 43. 101

In this subcategory, people express apology by only using the word ‗sorry‘

or ‗apologize‘ in English, or any other words from another language that

have the same meaning with ‗sorry‘ or ‗apologize‘, such as: the word

‗duìbuqi in Chinese.102 The examples are103:

in English : I‘m sorry; I apologize

b) by using apologizing words (i.e., sorry or apologize) and stating the favor or the fact

In this subcategory, besides using apologizing words such as ‗sorry‘ in English or any other words in other language which have the same meaning

with ‗sorry‘, the favor or the fact is also mentioned.104

The examples are105: in English : I'm sorry for the short notice; I‘m sorry for the delay

c) by using apologizing words (i.e., sorry or apologize) and mentioning the imposition caused by the favor

In this subcategory, besides using apologizing words, the imposition which is caused by the favor is also mentioned.106 The examples are107:

in English : I apologize for the inconvenience; I‘m sorry to take up your time; Sorry it took me so long to get it back to you.

d) by criticizing or blaming oneself

102

Ibid. p. 44. 103

Ibid. p. 44. 104

Ibid. p. 44. 105

Ibid. p. 44. 106

Ibid. p. 45. 107

In this subcategory, apology which is stated is in the form of criticizing or blaming oneself.108 The example is109:

in English : I‘m such a klutz!

e) by expressing embarrassment

The example is ‗it’s so embarrassing‘ in English.110

f) by using the Chinese phrase buhayoisi (embarrassed)

g) by using the Chinese phrase buhayoisi不好意思 and stating the favor

h) by using the Chinese phrase buhayoisi 不好意思 and mentioning the

imposition caused by the favor

i) by using Chinese expressions other than buhayoisi 不好意思 to show

embarrassment

5. Recognition of imposition

Recognition of imposition has three subcategories: a) by acknowledging the imposition

This kind of subcategory is expressed by acknowledging the imposition.111 In English, the example is: I know you didn‘t have to allow me extra time.112

108

Ibid. p. 45. 109

Ibid. p. 45. 110

Ibid. p. 45. 111

Ibid. p. 46. 112

b) by stating the need for the favor

In this subcategory, imposition is recognized by directly or indirectly stating how the speaker need for the favor.113 The examples are114:

in English : I really wanted to do my best on this, and this week has been so hectic. (indirect) ; I usually try not to ask for extra time, but this time I need it. (direct)

c) by diminishing the need for the favor.

This subcategory is expressed by diminishing directly or indirectly the need for the favor.115 In English, the example is: You didn‘t have to do that.116

6. Repayment

There are three subcategories which are categorized as repayment strategy. a) by offering or promising service, money, food or goods

In this subcategory, people try to state repayment of the favor by offering or promising service, money, food or good to the hearer.117 The example is118: in English : Can I buy you dinner and a beer for this?

b) by indicating his/her indebtedness

113

Ibid. p. 47. 114

Ibid. p. 47. 115

Ibid. p. 47. 116

Ibid. p. 47. 117

Ibid. p. 47. 118

In this subcategory, people try to express repayment by reaffirming and indicating his/her indebtedness to the favor giver (hearer).119 In English, the examples are: I owe you big time.; I owe you one.120

c) by promising future self-restraint or self-improvement

People express repayment by promising future restraint or self-improvement.121 In English, the example: It won‘t happen again.122

7. Other

Other strategy has four subcategories: a) Here statement

Here statement is generally expressed when someone wants to give something to someone else.123 In English, the examples are: Here‘s your book.; Here you go.124

b) Small talk

Small talk is utterance which is used to establish or enhance the intimacy or social bound between the speaker and hearer.125

119

Ibid. p. 47. 120

Ibid. p. 48. 121

Ibid. p. 48. 122

Ibid. p. 48. 123

Ibid. p. 48. 124

Ibid. p. 48. 125

c) Leaving-taking

Leaving taking is generally expressed when someone wants to leave someone else.126 In English, the example: Have a nice day!127

d) Joking

In English, the example: That's what you get for driving a truck. Just joking.128

8. Alerter

Alerter strategy has three subcategories: a) Attention getter

In English, the examples are: hey, hi, wow, whoa, oh, well, oh my god, by the way, you know.129

b) Title

In English, the examples are: Professor, Dr., Mr. Sir.130

c) Name (including first names, surnames or endearment terms)

In English, the examples are: John, Mary, Smith, Johnson, honey, dude, buddy, man, pal.131

126

Ibid. p. 49. 127

Ibid. p. 49. 128

Ibid. p. 49. 129

Ibid. p. 49. 130

Ibid. p. 49. 131

D.Rationale of Using Open-Ended DCT

There are some data collection methods which can be used to gather data in

production studies of speech acts, such as DCT, role play and observation.132 The differences are only in whether the gathered data naturally occurs or is specifically constructed.133 There are several reasons why the writer generally choose DCT and specifically choose open-ended written DCT as the instrument of the present study. First, the writer chooses DCT because it allows the writer to contrast responses among the participants toward specific comparable contexts, settings, and situations which become the focus of the writer.

DCT typically constitutes a written description of some situations in which each situation is then followed by a blank as a space for participants to write what they would say as responses if they were in that situation. Each situation in DCT questionnaire must describe a short description of the situation and setting, and the description of at least one comparable context which wants to be investigated, such as specification of social power or social distance between interlocutors.134

A contrastive analysis between interlanguage data produced by L2 learners in comparison with the data of NSs of L1 and L2 has to be conducted to investigate the occurrences of pragmatic transfer. As cited by Stine, Johansson argues that in doing contrastive analysis, the researchers have to know what to

132

Gila A. Schauer, Interlanguage Pragmatic Development: The Study Abroad Context, (New York: Continuum, 2009), pp.65-68.

133

Ibid. p.65.

134

compare.135 Hence, DCT is chosen because it allows the writer to formulate specific comparable contexts which become the focus of the study.

DCT do not ensure the validity that the responses which are elicited are the natural responses of the participants in their actual conversation. It is a disadvantage of using DCT. To solve it, observation may be a very ideal method since it can observe and found validity on which responseses that are truly appropriate as responseses for some certain situations. But, very few studies which use observation since it makes comparable contexts are difficult to examine in a structured way.136

DCT is the most relevant method in the present study. Besides NSs of Indonesian, the participants of the present study are NSs of American English and Indonesian learners of English who live in the US. This fact makes observation seems impossible since the writer who lives in Indonesia has limits in budget, access and time of the research. Besides DCT, there is role play which allows the researcher to gather data which can be specifically constructed and it is more spontaneous than the DCT. Role play is a method in which the researcher sets scenario of some situation, then, the participants are asked to be the actors to perform the provided scenario of some situations in pair.137 In the present study, role play may be more reachable than observation.

However, it is difficult to find the participants since this method takes their time and money to pay the bill of their internet to perform the scenarios of some provided situations. Even, if the participants want to spend their time and money

135

ibid. p. 49.

136

Gila A. Schauer (2009), op.cit..pp.65-66. 137

to do it, the target participants may get fatigue since they have to perform scenario of some situations in many times over and this fatigue may affect their performance.138 Hence, DCT is the most relevant method for the present study.

Eisenstein and Bodman compare the data which is elicited by written DCT with the data which is elicited by the other methods: questionnaire orally reading, role play, and observation. The result reveals that the data taken from DCT is almost identical to the data taken by the method when questionnaire orally reading, role play and natural situation, but they differ in the length of words and the prosodic features which are gathered since DCT do not provide prosodic

features such as participants‘ tone and intonation.139 Then, words elicited by DCT

seems shorter than transcript of orally gathered data since in the oral data there are repetition and searching for the right words which make it become longer.140

Third reason, this open-ended DCT allows the participants to respond some provided situations as long or as short as they wish to be appropriate responseses of given situations. Many studies on speech act realization in interlanguage pragmatic are amply documented using DCT, especially open-ended written DCT questionnaire, as an instrument which is used to elicit strategy/semantic formula of certain speech acts produced by participants. As explained previously, DCT consists of some provided situations in which each situation is then followed by blank as space which is provided for participants to write down their responseses. This kind of DCT is also called open-ended written DCT questionnaire.141

138

Ibid. p. 68.

139

Miriam Eisenstein and Jean Bodman (1993), op.cit. pp.69-70. 140

Stephanie Weijung Cheng (2005), op.cit., pp .25-26 141

In general, questionnaire—identically used in quantitative research—has to be developed by formulating conceptual definition, formulating operational definition and formulating lattices and indicators.142 But, developing DCT does not need the formulation of lattices and indicators which reflects certain theory. DCT only has to consist of some situations in which each situation have to describe the relationship between interlocutors, setting and the event/situation.143 DCT can be analyzed by either quantitative or qualitative.144

In 2005, Cheng used 8-items DCT which varies on the contextual factors of interlocutor familiarity, social status and imposition.145 Adopting the way how Cheng developed her DCT, in the present study, DCT consists of 18 situations which vary in three aspects: social status (S), ranking of imposition (I), and familiarity (F). The difference in social status a matter of the power structure in university. High-imposition favor is a favor which imposes the favor giver since it takes his/her time or money. Then, in the present study, the high-imposition favor is a favor which is done by the only person who can do it for the thanker.

The gratitude which is studied in the present study is expressions of gratitude after receiving a favor. The DCT is distributed by social media in the form of google doc questionnaire. The pilot study is not conducted due to limitation of time. Hence, almost all situations in the DCT which is employed in the present study are adapted from the DCTs which were previously distributed by Eisenstein and Bodman in 1986, Hinkel in 1992, and Cheng in 2005. Cheng uses

142

Muhammad Farkhan, Proposal Penelitian Bahasa & Sastra, (UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta: Adabia Press, 2011), p.35.

143

Stine Hulleberg Johansen (2008), op.cit. p.50. 144

Ibid. p.55.

145

demographic survey in questioning the background data of every participant.146 In

the present study, adopting Cheng‘s demographic survey, before and after every

participant is asked to respond to every given situation, some questions related to

participants‘ background information are provided.

Table 2. Description of DCT situations.

NO. SITUATION IN DCT STATUS IMPOSITION FAMILIARITY

1 Lending a pen + - -

2 Paying a book - + +

3 Allowing an interview - + =

4 Finding workbook & source book + + =

5 Rescheduling final exam - + -

6 Handing a tissue = - +

7 Lending a book + + -

8 Recommending some books - - -

9 Fixing a flash disk = + =

10 Showing the location of the

books - - +

11 Taking a pen = - =

12 Paying the bill of the food + + +

13 Taking a book - - =

14 Borrowing an important book = + -

15 Fixing a laptop = + +

16 Taking some sugar = - -

17 Taking scattered papers + - =

18 Giving a paper + - +

The 18 situations in the DCT which is employed in the present study to elicit expressions of gratitude in responding to favors are as follows:

1. Lending a pen (high-status, low-imposition, low-familiarity)

You are a mentor to some freshmen. At mentoring class, you need to write some information, but you realize that you left your pen at home. You ask for a pen. Jennie, a freshman who you just met a few days ago, lends you one. When you return it, you would say