See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285417570

TAP (Teacher learning and application to

pedagogy) through digital Video-Mediated

reflections

Chapter · January 2015

DOI: 10.4018/978-1-4666-8403-4.ch013

CITATIONS

0

READS

15

3 authors:

Poonam Arya

Wayne State University

19PUBLICATIONS 127CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Tanya Christ

Oakland University

33PUBLICATIONS 99CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Ming Ming Chiu

Purdue University

113PUBLICATIONS 2,046CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Handbook of Research on

Teacher Education in the

Digital Age

Margaret L. Niess

Oregon State University, USA

Henry Gillow-Wiles

Oregon State University, USA

Published in the United States of America by

Information Science Reference (an imprint of IGI Global) 701 E. Chocolate Avenue

Hershey PA, USA 17033 Tel: 717-533-8845 Fax: 717-533-8661 E-mail: cust@igi-global.com Web site: http://www.igi-global.com

Copyright © 2015 by IGI Global. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without written permission from the publisher. Product or company names used in this set are for identification purposes only. Inclusion of the names of the products or companies does not indicate a claim of ownership by IGI Global of the trademark or registered trademark.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

British Cataloguing in Publication Data

A Cataloguing in Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

All work contributed to this book is new, previously-unpublished material. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors, but not necessarily of the publisher.

For electronic access to this publication, please contact: eresources@igi-global.com.

Handbook of research on teacher education in the digital age / Margaret L. Niess and Henry Gillow-Wiles, editors. volumes cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4666-8403-4 (hardcover) -- ISBN 978-1-4666-8404-1 (ebook) 1. Teachers--Training of--Technological innovations. 2. Teachers--Training of--Research. 3. Educational technology. I. Niess, Margaret, editor of compilation. II. Gillow-Wiles, Henry, 1957- editor of compilation.

LB1707.H3544 2015 370.71’1--dc23

2015008257

This book is published in the IGI Global book series Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development (AHEPD) (ISSN: 2327-6983; eISSN: 2327-6991)

Managing Director: Managing Editor:

Director of Intellectual Property & Contracts: Acquisitions Editor:

Production Editor: Development Editor: Typesetter:

Cover Design:

334

Chapter 13

DOI: 10.4018/978-1-4666-8403-4.ch013

TAP (Teacher Learning and

Application to Pedagogy)

through Digital

Video-Mediated Relections

ABSTRACT

This chapter presents relevant indings from research that explored literacy teachers’ self-relections and relective discussions with peers that were mediated by digital video. Mixed methodological approaches were used, including statistical discourse analysis, which examines the relations between speech-turns in teachers’ video discussions to provide a ine-grained view of digital video’s mediating role. Findings showed that recursive viewing of videos, across diferent contexts or within a context facilitated shifts in purposes for discussing videos and broadened the foci of these discussions. Additionally, the situ-ated context and multiple modes of information presented in digital videos supported literacy teachers’ generation and application of ideas about reader processing and reader engagement. Teachers used certain conversation moves, such as critical thinking, hypothesizing, and challenging, as they transacted with the multimodal information in the video to support their generation of ideas for literacy instruction. Implications and future research directions are discussed.

Poonam Arya

Wayne State University, USA

Tanya Christ

Oakland University, USA

Ming Ming Chiu

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this chapter is to share what was learned through a research agenda across the last four years about using digital video as a tool to mediate literacy teachers’ reflections and reflec-tive discussions to inform practices for literacy teacher education in the digital age. Our interest in using digital video to mediate literacy teachers’ reflections and reflective discussions in reading practicum courses stemmed from the opportunities they provide for teachers to (1) consider multiple perspectives about pedagogy, (2) challenge their prior beliefs about teaching and shift or expand their pedagogical views, (3) understand the complexities of classroom literacy instruction, (4) consider the particular advantages and disad-vantages of different instructional practices for specific contexts to better analyze and respond to diverse instructional situations, (5) replay videos to learn recursively and address individual learn-ing needs, and (6) receive more useful specific feedback about their pedagogy (Boling, 2004; Copeland & Decker, 1996; Harrison, Pead, & Sheard, 2006; Kinzer, Cammack, Laboo, Teale, & Sanny, 2006; Tripp & Rich, 2012).

Despite this body of knowledge about the mer-its of digital video, however, little is known about how video mediates literacy teachers’ learning outcomes, such as their generation or application of ideas for their literacy instruction. In this chapter, we present a synthesis of the relevant findings from across our research agenda spanning 2010-2014 that highlights the mediating role of video used as a tool to facilitate literacy teachers’ learning during individual reflections and reflective group discussions with peers.

BACKGROUND

This section presents research that positions digital video as a tool in teacher education that enables authentic, context-oriented, reflective practice

within a collaborative and social environment. First, multimodal literacies and transactional perspectives are presented to contextualize the use of digital videos in teacher education. Second, the advantages of digital video for facilitating teachers’ learning are discussed. Third, research on video mediated self-reflections and reflection with peers is examined that offers multiple ways of using digital videos in teacher education.

Theoretical Perspectives

From a multimodal literacies perspective (e.g., Kalantzis & Cope, 2008), digital videos act as a form of “text” with which viewers can transact and construct meaning. This is similar to how readers engage in “complex, nonlinear, recursive” trans-actions with traditional text (Rosenblatt, 2004, p. 1371). However, digital video captures multiple modes of information (visual and auditory) that can present more complex pathways for processing information than transcriptions of oral accounts of teaching events alone (Kress, 2010; Wolfe & Flewitt, 2010). For example, video affords op-portunities to attend to many multimodal aspects of teaching events, such as facial expressions, gestures, and verbal interactions (Brophy, 2004; Koc, Peker, & Osmanoglu, 2009; Sherin & Han, 2004). Thus, digital video grounds discussions in ways that are “virtually impossible when referents are remote or merely rhetorical” (Ball & Cohen, 1999, p. 17).

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

thinking about and constructing meaning for teach-ing events, thus optimizteach-ing teachers’ individual growth within their zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978). Further, these processes support teachers’ abilities to collectively construct solu-tions to problems situated in the video that would be difficult to solve alone (Grossman, Wineburg, & Woolworth, 2001; Kinzer et al., 2006; Lave, 2004; Putnam & Borko, 2000; Vygotsky, 1978).

Advantages of Digital Video

for Teacher Education

Digital video has several advantages as compared to analog: ease of video capture, ability to edit video, ease of sharing, and ease of interactivity. These attributes support teachers as they use digital video to reflect on practices to expand and trans-form their understandings about pedagogy (e.g., Arya, Christ, & Chiu, in press; Christ et al., 2012; Christ et al., 2014; Christ et al., in press; Fadde & Sullivan, 2013; Harford & MacRuairc, 2008; Miller, 2009; van Es & Sherin, 2010).

Given the recent developments in video tech-nologies and easy access to relatively affordable video recorders, digital video is easy to capture (de Mesquita, Dean, & Young, 2010; Rich & Han-nafin, 2009; Savas, 2012). For example, built-in cameras in laptops, tablets, and phones, small portable video cameras with built in hard drives, and innovations like Flip cameras allow teachers to easily carry equipment around the classroom to record their instructional sessions. Also, digital videos tend to have good sound quality, due to the close proximity of the camera with built in microphone to the teacher and students. On the other hand, analog videos, or videos taken with cameras using mini digital cassettes, usually are cumbersome to collect because of multiple exter-nal microphones and wires stretching across the room and the need to change cassettes frequently, which can lead to gaps in the recording of events.

Digital videos, unlike analog videos, can be easily edited, allowing teachers to isolate and

tag segments of the video that feature behaviors of interest (de Mesquita et al., 2010; Kumar & Miller, 2005; McFadden, Ellis, Anwar, & Roehrig, 2014). The hands-on approach of re-viewing the video and producing short video clips that look at classroom instruction from different perspectives supports teachers’ development of pedagogical knowledge (Boling & Adams, 2008; Masats & Dooly, 2011). Additionally, editing digital videos this way has been linked to changes in teachers’ views about student thinking and learning as well as their own teaching practices (de Mesquita et al., 2010; Yerrick, Ross, & Molebash, 2005).

Digital video is stored as digital files that can be easily converted to a variety of formats, making it compatible with different hardware and software (de Mesquita et al., 2010; Savas, 2012). They can be viewed from the same machine on which they are captured immediately after recording is stopped, or easily shared across multiple platforms, operating systems, and applications (e.g., Google Drive or Dropbox) within minutes. Given the ease of storing, accessing, and sharing digital video files, they are simpler to use in a variety of ways for reflecting on teaching (Kumar & Miller, 2005; de Mesquita et al., 2010). Analog videos, on the other hand, need to be converted and transferred in a compatible format that might not always be possible and can be time consuming.

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

and development of shared knowledge,” (Masats & Dooly, 2011, p. 1160; McFadden et al., 2014; Zhang, Lundeburg, Koehler, & Eberhardt, 2011).

Digital Video-Mediated Reflections

Digital video-mediated reflections have been sug-gested as a means to bridge the “apparent chasm between what often happens in university-based teacher education and teaching in schools—a theory-practice gap” (Bencze, Hewitt, & Pedretti, 2001, p. 192). Digital video creates opportunities for teachers to view and refer to multiple modes of information embedded in the video. It also allows teachers to focus on this information within a spe-cific episode of instruction, and through complex transactions between viewers and video, come to understand pedagogy differently through analytic discussions (Lewis, Perry, & Murata, 2006; Tripp & Rich, 2012). Given the advantages of digital videos, two ways that video has been used as a dynamic multimodal source of information to deepen teachers’ reflective practices are worth further exploration: (1) self-reflection (includ-ing video edit(includ-ing) of one’s own teach(includ-ing, and (2) reflection on these events with peers.

Video-Mediated Self-Reflection

Video self-reflection provides a means for teachers to step back, explicitly notice what is important, and recognize discrepancies between what they remember occurred during instruction and actual evidence in the video (Rich & Hannafin, 2009; Sherin & van Es, 2005; Yerrick et al., 2005). The recursivity of digital video viewing (e.g., re-viewing, re-visiting, and zooming in on differ-ent segmdiffer-ents of the video), scaffolds what Schön (1987) referred to as reflection on action. Further, the ease with which digital videos can be captured and shared allows teachers to view the videos for self-reflection immediately or at a later time.

As part of self-reflection, teachers use video editing to select clips that they then share and

discuss with their peers in face-to-face or online contexts (e.g., Christ et al., in press; So, Pow, & Hung, 2009; van Es & Sherin, 2008). Researchers have found that the process of editing and anno-tating the video fosters deeper reflection on the part of the teachers by allowing them to process the video in many different ways, such as mak-ing connections between concepts, respondmak-ing to video content using different “observational frames,” and considering alternative interpreta-tions and soluinterpreta-tions (Beck, King, & Marshall, 2002; Calandra, Brantley-Dias, Lee, & Fox, 2009; Sanny & Teale, 2008; Sherin & van Es, 2005; van Es & Sherin, 2008).

Video-Mediated Reflection with Peers

The benefits of using digital videos are particu-larly conducive for teachers who come together to discuss videos of their own teaching with peers. Different names have been used by researchers to describe this practice, such as video-based

dialogue (Miller, 2009), video club (Sherin & van

Es, 2005), video analysis (Tripp & Rich, 2012),

and collaborative peer video analysis (CPVA;

Arya et al., in press; Christ et al., 2012; Christ et al., 2014). CPVA particularly focuses on the analytic component of peer discussions. The rela-tions between several aspects of these reflective discussions, such as purposes for which teachers select video clips to share, aspects of pedagogy they discuss, the conversation moves they employ, and sources of information they use, and their outcomes may be mediated by the use of digital videos. However, this mediation has not been explicitly explored in previous research.

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

of video in these discussions on teachers’ purposes and outcomes were not explored. Additionally, previous research has shown that teachers discuss several aspects of pedagogy, including methods and materials, students’ processing of information (e.g., reader processing in literacy), and issues related to student engagement (Brantlinger, Sherin, & Linsenmeier, 2011; Harford & MacRuairc, 2008; Koc et al., 2009; Llinares & Valls, 2009, 2010; Miller, 2009; Sherin & van Es, 2005). However, research has not explored how digital video mediates viewers’ transactions between the videos of their own teaching practices and their discussion of these specific aspects of pedagogy. Likewise, researchers have identified specific conversation moves used by teachers during these video-mediated discussions, such as recalling, probing, questioning, hypothesizing, agreeing, disagreeing, extending, connecting, and challeng-ing (Bolchalleng-ing, 2004; Juzwik, Caughlan, Heintz, & Borsheim-Black, 2012; Llinares & Valls, 2009; Miller, 2009; Sherin & van Es, 2005). However, research has not explored how video content is related to these conversation moves. Understand-ing these relationships is important to improve the use and efficacy of video-mediated discussions in literacy teacher education. Finally, previous research has identified that teachers use multiple sources of information in video-mediated discus-sions of pedagogy (Harford & MacRuairc, 2008; Koc et al., 2009; Llinares & Valls, 2009, 2010; Sherin & van Es, 2005; Smith, 2005). However, this research has not explored how these sources of information are related to literacy teachers’ video discussion outcomes. Particularly, this chapter focuses on two sources of information –video and discussion content.

Video-mediated discussions of teachers’ own pedagogy with peers may also support the appli-cation of ideas learned in this context to literacy teaching practices. While previous research has not explored literacy teachers’ application of ideas after video-mediated discussions, the broader research on teachers’ application of their learning

shows that when teachers apply their learning, this is often related to opportunities to do so (Lim & Kim, 2003; Lim & Morris, 2004-2005; Selzer, 2008). Given the situated context for learning in video-mediated discussions of literacy teachers’ own pedagogy, and the opportunity for applying this learning in subsequent lessons in their clinical practicum, it seems likely that teachers will apply at least some of what they learn to their literacy instruction.

VIDEO-MEDIATED REFLECTION IN

LITERACY TEACHER PREPARATION

This chapter presents research conducted over the past four years exploring video-mediated reflec-tions in literacy teacher preparation courses. After teachers captured their teaching events on digital video, they self-reflected on these individually, and then selected clips from the video to share and discuss with peers through collaborative peer video analysis (CPVA) (Arya et al., in press; Christ et al., 2012; Christ et al., 2014; Christ et al., in press). Self-reflections included (1) recursively viewing the video, (2) writing a reflective response based on guiding questions provided by the professor (e.g., What did you do well? What did not go so well? What would you do differently next time?), and (3) selecting a clip from the video to share with peers for CPVA and identifying a focus for the discussion. CPVA included (1) a teacher present-ing the clip s/he selected and sharpresent-ing the purpose that she identified through her self-reflection, (2) the teacher and her colleagues dynamically view-ing and re-viewview-ing this clip together, and (3) their discussion of the content of the clip to generate new pedagogical ideas that could be applied to this teacher’s literacy practices.

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

relevant findings from these studies related to how digital video mediates literacy teachers’ learning through the complex, recursive transactions with it are presented. Finally, recommendations for the use of digital videos in literacy teacher preparation that are based on the findings from these studies are discussed.

Methods

The research team conducted a series of studies about CPVA. Arya and Christ were the professors of the courses in which the research was conducted. All course enrollees were invited to participate in the research. No incentive or penalty was given for participation. The courses involved two-semester reading clinic practica that focused on literacy assessment and assessment-based instruction (for studies 1, 2, 3, and 4) and an undergraduate service-learning course (also included in study 4). All graduate-level teachers in these studies taught literacy at some level from K-12, and undergraduate students were studying to become elementary school teachers. Only studies 2 and 3 share the same dataset and participants. All other studies presented here have unique datasets and participants.

Before teachers in the studies engaged in CPVA, they all had participated in video case-study discussions that were facilitated by the professors in their respective reading practicum courses. Thus, teachers had some guided experi-ence engaging in analysis of literacy events to set a foundation for engaging in CPVA. Also, all teachers had an opportunity to edit and self-reflect on the video of their literacy teaching practices as part of the process of selecting video clips and foci for the CPVA discussions.

Study 1

This study framed the broader context in which CPVA was used in our teacher education courses by qualitatively exploring the breadth and depth

of 18 female graduate-level literacy teachers’ reflections across three contexts in their reading clinic practicum courses: video case-study reflec-tions, video self-reflecreflec-tions, and CPVA (Christ et al., in press). Reflections had two steps that were part of the coursework: (1) transactions between viewer and video (used as a multimodal text) to construct understandings about the teaching event, and (2) written responses to guided written reflection templates (as suggested by McFadden et al., 2014). To encourage candid responses on the written reflection templates, points were given for simply completing these assignments.

A total of 133 video case-study reflections, 55 video self-reflections, and 50 CPVA reflections were collected as data sources. Ideas that teachers stated they learned in these video-mediated reflec-tions were organized in a database. A teacher’s ideas about an issue that she reflected on across multiple contexts over time were organized across multiple columns (one column for each reflective response) within the same row. A teacher’s ideas that were about different issues were organized on different rows. Thus, information across rows reflected breadth of ideas on which a teacher re-flected, and information across columns reflected the depth of reflection a teacher engaged in about an issue.

Grounded theory, including emergent coding and constant comparative analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), was used to identify categories and themes that reflected the patterns of teachers’ development of depth and breadth of ideas about literacy pedagogy across the three video-mediated reflective contexts. Arya and Christ coded all data, and discrepancies were reviewed and discussed to achieve consensus.

Study 2

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

conducted. These discussions occurred amongst 14 female graduate-level teachers enrolled in read-ing clinic practicum courses (Christ et al., 2012). As part of the course requirements, all teach-ers were asked to select and share at least one instructional and one assessment video clip of their practice for CPVA. Teachers were asked to select a video clip from their practice that they wanted to share and discuss with their peers, and explain why they chose the clip when they presented it for CPVA. Most teachers chose to share more than the required two video clips, stating that they wanted additional feedback from their peers on their practices. Anecdotally, teachers commented that they found CPVA useful in helping them generate ideas to improve their pedagogy.

All CPVA events were video-recorded and transcribed for analysis. For each CPVA event, we identified whether the video clips teachers chose were of assessment or instruction. A combination of codes used in previous research (Calandra et al., 2006; Harford & MacRuairc, 2008; Miller, 2009) and emergent coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2008) were used to categorize the purposes for which teachers chose their clips to share (i.e., sharing an explicitly visible problem, an implicit problem, or a success) and the aspects of pedagogy that were discussed (i.e., literacy methods/materials, reader engagement, or reader processing). The codes were iteratively developed, applied, and revised until the first two authors (Arya and Christ) were in agreement. Both the use of previous codes and rigorous emergent coding development ensured the validity of these codes. Finally, Arya and Christ coded all the data independently, and developed consensus for any disagreements. Inter-rater reli-ability was calculated using Krippendorf’s (2004) α. Krippendorff’s (2004) α was used because it can be applied to incomplete data, any sample size, any measurement level, any number of cod-ers or categories, and scale values. Ranging from -1 to 1, an α exceeding 0.66 showed satisfactory agreement. The mean inter-rater reliability for all codes in this study was .88, indicating

suf-ficient reliability for analysis. Next, a constant comparative method (Corbin & Strauss, 2008) was used to identify patterns that described how teachers’ purposes for sharing videos and aspects of pedagogy discussed were related across the 39 CPVA events.

Finally, two discussion outcomes were coded: teachers’ generation of ideas that could be ap-plied to literacy teaching practices to address the situation in the video, and teachers’ expressions that they were considering applying these ideas to their practice. Then, preliminary statistical analyses were conducted to identify the relations between purposes for sharing video clips and these outcomes. As the dataset had (a) missing data, (b) multiple outcomes, (c) indirect media-tion effects and (d) false positives, ordinary least squares regressions were inadequate. To address each of these issues, we used the following: (a) MCMC-MI to estimate the values of the missing data as discussed above (Peugh & Enders, 2004),

(b) Zellner’s method systems of equations to model

multiple outcomes (Kennedy, 2008), (c) Sobel mediation test to test for mediation (Kennedy, 2008) and (d) two-stage linear step up procedure to reduce false positives as discussed above (Ben-jamini, Krieger, & Yekutieli, 2006).

Study 3

dis-TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

cussed (reading level, word recognition, fluency, comprehension, vocabulary, writing), sources of information (prior knowledge, video, general knowledge about the student, course readings), and conversation actions (recalling, probing, explain-ing, connectexplain-ing, thinking critically, challengexplain-ing, affirming, suggesting, hypothesizing).

A total of 1,525 conversation turns were coded. To ensure validity both codes from pre-vious research (Boling, 2004; Calandra et al., 2006; Harford & MacRuairc, 2008; Miller, 2009; Koc et al., 2009; Llinares & Valls, 2009; 2010; Sherin & van Es, 2005; Smith, 2005) and rigorous emergent coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2008) were used. Two graduate students were trained, and coded the data when their application of codes was consistent. Discrepant codes were discussed to achieve consensus and those codes were used for statistical analyses. Krippendorf’s (2004) α showed adequate inter-coder reliability for all variables (M = 0.75).

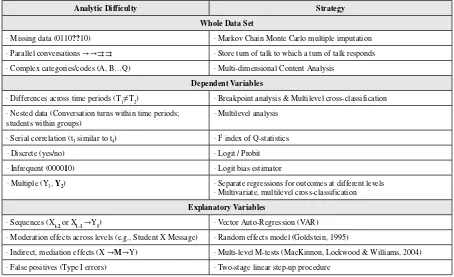

Finally, the relations between all coded factors and attributes of teachers’ turns of talk were tested using Statistical Discourse Analysis (SDA), which addresses several analytic challenges (see Table 1; Chiu, 2008). SDA identifies watershed events that radically change the participant(s)’ behaviors and models the likelihood(s) of specific behavior(s) at each moment in time with explanatory variables at different levels: attributes of recent behaviors (micro-time context), time periods, individuals, groups, organizations, etc. Using SDA, teacher outcomes were modeled using a multilevel, multi-variate, cross-classification logit model. An alpha level of 0.05 and a two-stage linear step-up proce-dure were used to reduce false positives (Benjamini et al., 2006). The total effect of the odds ratio is reported using percentage of increase or decrease in likelihoods of outcomes to make them easier to understand (Kennedy, 2008). Robustness tests were used to analyze single outcomes, multilevel

Table 1. Statistical discourse analysis

Analytic Difficulty Strategy

Whole Data Set

· Missing data (0110??10) · Markov Chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation

· Parallel conversations →→⇉⇉ · Store turn of talk to which a turn of talk responds

· Complex categories/codes (A, B…Q) · Multi-dimensional Content Analysis

Dependent Variables

· Differences across time periods (T1≠T2) · Breakpoint analysis & Multilevel cross-classification · Nested data (Conversation turns within time periods;

students within groups)

· Multilevel analysis

· Serial correlation (t3 similar to t4) · I2 index of Q-statistics

· Discrete (yes/no) · Logit / Probit

· Infrequent (000010) · Logit bias estimator

· Multiple (Y1, Y2) · Separate regressions for outcomes at different levels

· Multivariate, multilevel cross-classification

Explanatory Variables

· Sequences (Xt-2 or Xt-1 →Y0) · Vector Auto-Regression (VAR) · Moderation effects across levels (e.g., Student X Message) · Random effects model (Goldstein, 1995)

· Indirect, mediation effects (X →M→Y) · Multi-level M-tests (MacKinnon, Lockwood & Williams, 2004)

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

models; separate halves of the data set; and the original data set (without any estimated data).

Study 4

To extend previous understandings about the im-pact of CPVA on teachers’ literacy pedagogy, a subsequent study examined to what extent 48 male and female undergraduate-level and nine female graduate-level teachers, who were taking literacy practicum courses with Christ, self-reported ap-plying ideas that were generated during CPVA, what kinds of pedagogical ideas they applied, and how modes of information were related to their application of these ideas (Christ et al., 2014).

Immediately following CPVA discussions, using a guided response sheet, teachers docu-mented their learning, sources of information that contributed to their learning, and application of this learning to their teaching in their practicum courses. These responses were given full credit when submitted, regardless of content, to reduce the incentive to generate a response focused on attaining a particular grade. A total of 227 response sheets were collected; graduate-level teachers completed 44 and 183 were completed by undergraduate-level teachers.

Codes for the kinds of pedagogical ideas that teachers learned and the sources of information that supported their learning were based on cat-egories used in previous research, thus support-ing their validity (Harford & MacRuairc, 2008; Miller, 2009; Koc et al., 2009; Sherin & van Es, 2005). Additional categories were also identified through rigorous emergent coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Arya and Christ coded all instances of teachers’ learning recorded on the response sheets for content. Krippendorf’s (2004) α for pedagogical ideas learned was 0.97, showing high inter-rater reliability.

Analytic difficulties involved both the outcome variables (multilevel or nested data, discrete outcome) and the explanatory variables (indirect mediation effects, false positives). To properly

model multilevel discrete outcomes, multilevel logit (Goldstein, 1995) was used. Mediation was tested across levels of data with multilevel mediation-tests (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001) and minimized false positives with the two-stage linear step-up procedure (Benjamini et al., 2006). Unlike SDA in study 3, this analysis does not model time or examine conversation turns.

Findings

This section presents and discusses only the find-ings from the studies presented in the Methods section that are salient to the role of digital video in mediating teachers’ learning during CPVA. Other results from these studies are reported in the original publications (Arya et al., in press; Christ et al., 2012; Christ et al., 2014; Christ et al., in press).

Study 1

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

she could use peer support to construct deeper understandings about her literacy practices.

Previous research showed that teachers could notice things that they did not notice in-the-mo-ment of teaching, think critically about practices, and identify problems and solutions when using video for reflection (Downey, 2008; Holling-worth, 2006; Rich & Hannafin, 2009; Santagata, Zannoni, & Stigler, 2007; Yerrick et al., 2005). Our findings extended this body of research by showing that across multiple reflective contexts (i.e., self-reflection and CPVA) literacy teachers engaged in greater depth of reflection that led to identifying more problems and solutions than occurred through reflecting in any one context (i.e., self-reflection, or CPVA).

Study 2

The findings from this study showed that literacy graduate-level teachers chose clips to share in CPVA for three purposes: sharing a success, shar-ing an implicit problem, and sharshar-ing an explicit problem. During CPVA discussions, however, foci were often clarified or extended through the transactions with the video. The mediating role of video was particularly important when teachers discussed problems related to reader processing, as is the case in the following vignette in which Darcy discussed her difficulty helping her student identify long and short vowels in words. At the beginning Darcy explained why she chose the video clip:

I had been working on long-vowel sounds with her. I have never seen a student like her. She tries the short-vowel sound for every single word that she doesn’t know. So anyways, we had done this whole lesson on double-O and what sound it makes and she knows that every single one of these [word] cards will have the same double-O sound, but she still goes for short-vowel sounds.

While she did not articulate it explicitly, her implicit problem was that she needed help under-standing how to support her student in analyzing vowel patterns. After viewing the video with her colleagues, Darcy extended her questions, refer-ring to the video, to add more information to the initial implicit problem, and identified a second explicit question to discuss:

So she just tries to always say the short sound—and you could see her looking away [in the video], not even looking at the word. She’s just guessing any random word that starts with the letter F. You can probably tell from that [video], my student is very wiggly when she reads. But I, when I was watching her video, just part of it, I was watching with, with no sound, she almost rocks back and forth, like as she’s reading and I don’t know if anyone has seen a kid do that, or if you think that’s helping her to focus. I was going to ask about that as well. So I guess I have two questions.

Primarily, Darcy was using visual information in the video to deepen her understanding of her reader’s processing and share this critical infor-mation with her colleagues. Without the visual clues, it would be impossible to understand that the reader was not attending to the letters, and this was the crux of the problem related to her misidentification of vowel sounds in words.

Similarly, when Gabby presented her video to her colleagues for CPVA, her problem at first was vague:

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

About two minutes into the conversation Gabby forwarded the video, played a new segment, and extended her explanation of her problem:

Right there, I’m trying to ask more probing ques-tions but every probing question doesn’t get me an answer so I try to think of other ones and I’m fiddling with the paper [in video] and I think that … You know, it was funny because I read this with him. I read the story before, I read it after, I read it during, creating my retelling guide. I read my retelling guide like seven times. I got it down pat and then you’re sitting in front of him and other things are coming out or things are not coming out and he’s telling me basics and when I’m asking questions, nothing’s... there’s no flow. So I think next time, even though I know we should take some paper and check it off, personally, I would just like to put that down in front of me, I think, next time and just use my head to ask the questions going along because then I’m trying to think of what he said--what’s a good probing question? What did he miss here? Is there something I can help him connect? I look like I’m nervous but that was the whole thing of what was going on in my brain at that time. I don’t know if that spilled onto him, too.

Both the auditory and visual information provided in Gabby’s video were critical to un-derstanding the situation. Viewers had to hear Gabby’s open-ended prompts and see her looking back at her papers for help. They had to see the student’s facial expressions as he struggled to an-swer Gabby’s questions, and Gabby’s subsequent fiddling with her papers as she struggled to elicit what he understood about the text. In response to viewing the video that showed Gabby’s difficul-ties, Linda suggested that she could use “bullet points” instead of “everything written out” and Julia suggested, “Try to use the same words and vocabulary that they [the student] gave the infor-mation…Like if they gave me ‘she went to the park’…I underlined that and then after …I need to go back and be like, okay, you mentioned this.”

Thus, the mediating role of the multiple modes of information afforded by the video is critical because it helped literacy teachers articulate their problems regarding the situated instruction that was being discussed. This is important because the findings showed that when literacy teachers articulated problems, they were more likely to generate ideas that could be applied to address the issues in the video (Christ et al., 2012).

Previous research showed the recursive pos-sibilities of replaying video to support teachers’ learning (Kinzer et al., 2006). The findings in our study extended prior research by identifying a specific way that this occurs—by providing opportunities for questions about pedagogy to unfold and be sharpened through CPVA discus-sions (Christ et al., 2012).

Study 3

The findings of this study showed that the pur-poses for sharing video clips were statistically related to teachers’ outcomes. Specifically, literacy teachers who shared a success were 54% more likely to express that they intended to apply an idea generated during the CPVA discussion to their practice (Arya et al., in press). For example, through self-reflection, Carrie identified a video clip that showed her student “making really good progress” predicting during reading. Subsequently, when she shared and discussed the information in the video clip during CPVA, the following exchange ensued:

1a. Carrie:I’m trying to get him to make the

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

that it was a spider, but he didn’t get them all right.

1b Karen:When you read another book, what

if you put like little tiny flags, when they got to a certain part to stop and to make a prediction without you saying anything. When they read it, they see that sticker—that flag—they have to stop, make a prediction and then keep going. And you randomly place them throughout the book.

1c. Lucy:It was similar with my seventh grader,

but one day I ripped out all my stopping points and I just told him at the beginning of the reading, okay, today you’re going to tell me when it’s a good time to stop.

1d. Karen:What if you had like the Post-its but

like one would be to predict and he’d have however many. Like yellow would be predict, blue would be something else, and he can use however many he wants. But he has, say try to use this many during the reading.

1e. Carrie:Yes, I could use those with both of

my students, more than one [idea], too. Be-cause even today, I just feel like I’m holding their hand too much. Like I have to let them predict on their own or know when to stop on their own.

During CPVA, Carrie repeatedly drew her col-leagues’ attention to what the student and she were doing in the video clip. This action prompted her colleagues to suggest some additional methods/ materials that Carrie could use to further help her student. Carrie expressed an interest in applying the ideas generated during the discussion in the future, towards a potentially even more successful end. This highlights the important role video played in providing a shared experience that allowed teachers to collaboratively construct ideas that could be applied to the specific literacy instruc-tion situainstruc-tion portrayed in the video.

Additionally, this study identified that the multiple modes of information afforded in video al-lowed literacy teachers to collaboratively transact

and construct understandings about certain aspects of pedagogy, such as reader processing and reader engagement that could not be constructed without the video sources of multimodal information (Arya et al., in press). For example, the following oc-curred when Sharon and her colleagues discussed her reader’s prosody. Sharon explained the issue before showing the video clip:

This student struggles a lot with the prosody in his voice. His voice is so robotic and monotone and I worked on that in every session, at least hit it a couple times and I did three sessions wholly dedicated to it and Darcy did one. And it’s weird because he will seem like he gets it and then when he does use voice or what he calls voice, he takes on like a different character. So this clip just kind of personifies that because it shows him being very monotone and then at the very end, he does like this weird... I mean, it’s cute. It’s like his personality is kind of coming through a little bit because he’s a little goofy and that’s nice to see because overall, he’s very quiet and shy. But at the same time, I don’t know how to instruct him to try to apply that to his regular voice.

Then, she and her colleagues discussed the video as is demonstrated in the vignette below:

2a. Karen: I was very surprised to hear how

robotic he sounded. I guess I wasn’t expect-ing it to be like that.

2b. Sharon: Even his mom, when we had the

conference, said the same thing…that he doesn’t talk very much and when he does, it’s very like [monotone].

2c. Karen:Then maybe that’s why he can’t so

it…because that’s how he talks.

2d. Darcy:It’s like a character voice [when he

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

2e. Sharon: So he could do that [read with

expression]…I feel like it’s almost a con-fidence thing. That the, you know, he has more confidence when he’s out of [his own] character…I like that [idea] though, the recording, recording his voice…I’ll try the recording if I have time in one of the sessions.

Based on having heard Sharon’s student read in the video, the other teachers were better able to hypothesize and support Sharon in figuring out why he was reading that way. Further, they were able to generate an idea that Sharon expressed an interest in applying to her literacy instruction.

Similarly, in another CPVA event, the multi-modal information in the video supported teachers’ generation of understanding about and ideas for literacy instruction related to reader engagement. For example, Karen shared the difficulty she was experiencing trying to get her student engaged:

I really struggle and it’s every time…he’s like this and I cannot get him to talk to me…I don’t know what to do because I’m not sure if he’s not understanding. I’m not sure if he’s just not talking to me. So this is kind of like I, I’m try-ing. This is the second time I’m talking about a grandma and I had said to him, I had said, “Oh, do you see your grandma a lot?” And he’s like, “No.” And I say, “Oh, okay, you don’t see your grandma then?” He’s like, “No.” I say, “Can you tell me something special, like when you see your grandma?” He’s like, “I don’t know.” So I’m going to talk about what about my grandma [in the video clip], thinking hopefully this will make him say something to me. But it doesn’t…We sat here so quiet for a while.

Then, Karen played the video clip, and at the end she explained:

[I] find out that his grandma comes over every Tuesday. She’s over every Tuesday! So, I finally get him to answer me but, I mean, this is 30

min-utes after we started this conversation—to get something! Sometimes I’m just pulling teeth. I don’t know what it [means].

Next, Karen and her colleagues discuss the verbal and non-verbal behaviors in the video:

3a. Darcy:Just watching him [in the video]...I

could tell he’s very shy and reserved and quiet. But he seemed very interested in the shark book [in the previous week’s video]. When you came next to him to read to him, he was really looking at every page and very into it.

3b. Karen:A whole big chunk of our time is like

that.

3c. Darcy:Then he stopped. He did stop though

[in the video]. Once you got into that [grandma] book.

3d. Sharon: So you need narrative text about

sharks, and bats, and not grandmas. Maybe his grandma’s mean. Do you know her? Have you met her?

Through the use of both visual and auditory information in the video, the teachers in this CPVA group were able to help Karen understand her reader engagement problem better, and identify ideas to address it.

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

student in the video was provided. For example, in line 3a, Darcy refers to student information in the video (“I could tell he’s very shy and reserved and quiet”), and then three turns later, in line 3d, Sharon generates an idea about reader engage-ment (“So you need narrative text about sharks, and bats, and not grandmas”).

Further, teachers’ conversation moves facili-tated transactions between viewers and the video to construct these understandings. For example, when teachers engaged in critical thinking, they were 37% more likely to generate an idea about reader engagement and 30% more likely to gener-ate an idea about reader processing that applied to the child in the video. For example, in line 2d, Darcy critically analyzes the student’s reading based on hearing it in the video, and this results in her generation of an idea about reader processing (“He changes it to become like a character. It’s not his voice with expression.”). Likewise, when teachers engaged in hypothesizing, they were 6% more likely to generate an idea about reader engagement and 1% more likely to generate an idea about reader processing regarding the child in the video. For example, in line 2e, when Sharon hypothesizes that “he has more confidence when he’s out of [his own] character”) she generates the idea that “he could do that [read with expres-sion]” just within the constraints of reading in character. Similarly, when a teacher challenged another teacher’s ideas, then two and three turns later teachers were 8% and 2%, respectively, more likely to generate ideas about the engagement of the reader in the video.

These findings show the dynamic transactions that occurred during CPVA between teachers on each conversation turn, the content of the video that portrayed the student and teacher, and how these transactions affected later discussion turns and constructions of understandings about literacy practices. These results extend the existing re-search in two ways. First, previous rere-search identi-fied that theoretical knowledge, prior experiences, and video content were important for informing

video discussions (Copeland & Decker, 1996; Harford & MacRuairc, 2008; Koc et al., 2009; Llinares & Valls, 2009; 2010; Sherin & van Es, 2005; Smith, 2005). Our research extended these findings to show that referring to student informa-tion in the video specifically supports teachers’ generation of ideas about reader processing and reader engagement. Second, previous research showed that video used as part of discussions of teachers’ own practices supported teachers’ generation of ideas for pedagogy (Harford & MacRuairc, 2008; Sherin & van Es, 2005). Our research further showed that using video to mediate teachers’ reflective discussions about their literacy teaching practices is critical for generating ideas for specific aspects of literacy teaching, such as reader processing and reader engagement.

Study 4

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

head.” Marcie finally concluded that her student did not lack interest, but was frustrated because he was unable to identify the word. To address her student’s difficulty, Marcie later reported that she selected a text for her next lesson that was culturally relevant, to support the student’s use of prior knowledge to decode unfamiliar words. We triangulated this self-report by checking her lesson plan and our observational notes about her subsequent session, which confirmed that she used culturally relevant text.

Additionally, when teachers used information from both video and discussions, they were 48% more likely to report that they applied the ideas generated during CPVA to their literacy teaching practices. For example, Jenna, a graduate student, noticed in a peer’s video that in order for the student to apply the “sounding out” strategy, the teacher had to model this strategy. Also, during the discussion of this video clip, another teacher sug-gested that using manipulatives, such as magnetic letters, would be an effective way to provide both modeling and scaffolding for the “sounding out” strategy. Jenna reported that she subsequently used manipulatives to provide modeling and scaffold-ing for this strategy to support the reader she was teaching in her reading clinic practicum course. This result shows the importance of both the video as a mediating source of multimodal information and the importance of teachers’ constructivist interactions through discussion. Together, video and viewers transact dynamically to best construct understanding of literacy pedagogy.

Our findings extended the limited research on teachers’ application of learning (Tripp & Rich, 2012; van Es & Sherin, 2010) by showing the extent to which literacy teachers’ apply their learning when video is used.

Recommendations

Based on the relevant findings presented from this set of research studies related to the mediat-ing role of video in self-reflection and reflective

discussions with peers, five recommendations are made for literacy teacher education.

First, literacy teacher educators should provide opportunities for multiple layers of video reflec-tion to facilitate teachers’ noticing problems and generating ideas to solve these problems in their literacy teaching practice. Recall that teachers often identified video-clips and foci for CPVA through self-reflections, but then the foci shifted through the video-mediated conversations. Thus, re-viewing the videos across multiple contexts broadened teachers’ foci on pedagogical issues and subsequently their opportunity for generating ideas about literacy pedagogy.

Second, literacy teacher educators should al-low teachers to select video clips to share through CPVA for their own purposes, and provide time and space for these purposes to unfold based on how viewers transact with the video and one another. This activity supports literacy teachers’ development of questions that they might not have been able to articulate prior to sharing the video. If teacher educators insist on teachers discuss-ing only the purposes that they identify durdiscuss-ing self-reflection, then teachers might not have an opportunity to take advantage of the affordances of digital video to mediate understandings in a social context. By re-visiting and re-viewing the information in the video with their peers during CPVA, teachers can discuss additional issues that emerge through the interactive process. Thus, both the social context and video as a multimodal information source are critical to the breadth of issues that literacy teachers notice and identify during video-mediated discussions.

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

transactions that occurred between teachers and the video as they generated ideas about literacy practices.

Fourth, literacy teacher educators should use video-mediated collaborative discussions, like CPVA, to support teachers’ generation of ideas to help them understand reader processing and reader engagement in particular. Providing the situated context and multiple modes of information for literacy events via digital video was necessary for understanding these more complex issues in literacy instruction. These issues require both auditory (e.g., reading aloud, sighing, comments about text, etc.) and visual (e.g., eye-movement, body language, pointing, etc.) information for teachers to observe, analyze, and interpret a stu-dent’s behaviors and generate new ideas to apply to their practice through CPVA discussions, that the digital video provided. Further, these discus-sions, rooted in analysis of the multiple modes of information provided by the digital videos, supported teachers’ application of their learning about reader processing to their practice.

Fifth, teacher educators should encourage literacy teachers to engage in conversation moves that use the multiple modes of information afforded by video to support their generation and applica-tion of ideas about reader processing and reader engagement, such as critical thinking, hypoth-esizing, and challenging peers’ ideas about what occurred in the videos. These actions support the transactional process between viewers and video.

Finally, while our findings and recommenda-tions focus specifically on literacy teacher educa-tors, these may also apply to teacher education in other content areas. The learning processes and outcomes facilitated by digital video use across our research, as presented above, are unlikely to be germane only to literacy, but rather these may be more broadly applicable. This, however, is an open question that warrants future research.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Based on this body of research about the use of digital video-mediated self-reflections and reflec-tive discussions in literacy teacher education in the digital age, future research should explore the following:

1. Determine whether results differ across lit-eracy teachers, especially exploring teacher demographic variables, including grade levels taught, teaching experience, educa-tion, race, gender, and age;

2. Examine how the experiences and prior knowledge that literacy teachers bring to digital video reflections affect their discus-sion processes and outcomes;

3. Investigate the benefits of literacy teachers’ sharing of successes in CPVA, and whether helping teachers to analyze why successes occurred might help teachers to learn what they could or should do as part of their pedagogy;

4. Collect and analyze teacher interview data and observations of applications of learning to further understand and triangulate teacher learning and its application;

5. Conduct a comparative analysis of outcomes from self-reflections and collaborative peer video analysis (CPVA) with similar discus-sions in which teachers do not use video; 6. Compare CPVA discussions of teachers’ own

teaching to video-mediated discussions not of their own teaching, to see how the video being of their own pedagogy affects the process and outcomes of discussions; and 7. Use Statistical Discourse Analysis (SDA,

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

CONCLUSION

This chapter is grounded in a view of digital video as a multimodal source of information that can be used to generate ideas for literacy practice through dynamic transactions between viewers and video during video-mediated reflective discussions that present situated practices (Greeno, 2003; Kalantzis & Cope, 2008; Kress, 2010; Lave, 2004; Rosenb-latt, 2004; Vygotsky, 1978; Wenger, 2001; Wolfe & Flewitt, 2010).

We presented previous research on the advan-tages of digital videos for teacher education and the existing research on video-mediated reflections. This information advised the need for research about how digital video mediates literacy teachers’ learning through video-mediated self-reflections and reflective discussions with peers, which was the focus of this chapter.

Our findings showed that recursive viewing of videos, both across contexts (self-reflection, then CPVA) or within a context (re-viewing) facilitated shifting purposes for discussing videos and broad-ened the foci of these discussions. Additionally, video was a critical source of multiple modes of information to support teachers’ generation and application of ideas about certain aspects of literacy pedagogy—namely, reader processing and reader engagement. Further, teachers used certain discussion moves as they transacted with the multiple modes of information in the video to support their generation of ideas for literacy instruction. These moves included critical think-ing, hypothesizthink-ing, and challenging.

The findings of both previous research and our research strongly support the use of digital video to mediate viewers’ transactions in the social context of discussions of teachers’ own practices. The implications for literacy teacher education include encouraging teachers to (1) engage in multiple video-mediated reflective contexts, (2) select videos for their own purposes, (3) self-direct their viewing process, (4) use video to mediate discussions about reader processing and reader engagement, and (5) use discussion moves such as

critical thinking, hypothesizing, and challenging when transacting with the video to generate ideas to address the situated practice.

Our body of research presented in this chap-ter extended previous work by showing that (1) teachers reflected more deeply when they engaged in multiple video reflection opportunities; (2) re-cursive viewing of digital videos helped teachers sharpen their questions/foci during discussions; (3) video’s mediating role was critical to teach-ers’ generation of ideas for reader processing and engagement; (4) teachers applied their learning based on using digital video as a source of informa-tion; and (5) using Statistical Discourse Analysis (SDA) provided a means for exploring the relations between the actions within specific conversation turns (during digital video-mediated discussions) and teacher learning outcomes.

Future research might use SDA to better un-derstand the dynamic processing that occurs in video-mediated discussions about pedagogy. It might also explore broader teacher demograph-ics and data sources (e.g., interviews), as well as comparisons between digital video-mediated discussions and those discussions without video, to identify their differences in process and outcomes. Finally, this line of research might be extended to other content areas, to examine its generalizability to other content areas in teacher education.

REFERENCES

Arya, P., Christ, T., & Chiu, M. M. (in press). Links between characteristics of collaborative peer video analysis events and literacy teachers’ outcomes.

Journal of Technology and Teacher Education.

Ball, D., & Cohen, D. (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Towards a practice-based theory of professional education. In G. K. Sykes & L. Darling-Hammond (Eds.), Teaching as learning

profession: Handbook of policy and practice (pp.

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

Beck, R. J., King, A., & Marshall, S. K. (2002). Effects of videocase construction on preservice teachers’ observations of teaching. Journal

of Experimental Education, 70(4), 345–361.

doi:10.1080/00220970209599512

Bencze, L., Hewitt, J., & Pedretti, E. (2001). Multi-media case methods in pre-service science education: Enabling an apprenticeship for praxis.

Research in Science Education, 31(2), 191–209.

doi:10.1023/A:1013121930945

Benjamini, Y., Krieger, A. M., & Yekutieli, D. (2006). Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika, 93(3), 491–507. doi:10.1093/biomet/93.3.491

Boling, E. (2004). Preparing novices for teach-ing literacy in diverse classrooms: Usteach-ing written, video, and hypermedia cases to prepare literacy teachers. National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53 (pp.130–145). Chicago, IL: National Reading Conference.

Boling, E., & Adams, S. (2008). Supporting teacher educators’ use of hypermedia video-based programs. English Education, 40(4), 314–339.

Brantlinger, A., Sherin, M. G., & Linsenmeier, K. A. (2011). Discussing discussion: A video club in the service of math teachers’ national board preparation. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and

Practice, 17(1), 5–33. doi:10.1080/13540602.20

11.538494

Brophy, J. (Ed.). (2004). Using video in teacher

education. The Netherlands: Elsevier.

Calandra, B., Brantley-Dias, L., & Dias, M. (2006). Using digital video for professional development in urban schools: A preservice teacher’s experience with reflection. Journal of Computing in Teacher

Education, 22, 137–145.

Calandra, B., Brantley-Dias, L., Lee, J. K., & Fox, D. L. (2009). Using video editing to cultivate novice teachers’ practice. Journal of Research on

Technology in Education, 42(1), 73–94. doi:10.1

080/15391523.2009.10782542

Chiu, M. M. (2008). Flowing toward correct con-tributions during groups’ mathematics problem solving: A statistical discourse analysis.

Jour-nal of the Learning Sciences, 17(3), 415–463.

doi:10.1080/10508400802224830

Christ, T., Arya, P., & Chiu, M. M. (2012). Collaborative peer video analysis: Insights about literacy assessment & instruction.

Jour-nal of Literacy Research, 44(2), 171–199.

doi:10.1177/1086296X12440429

Christ, T., Arya, P., & Chiu, M. M. (2014). Teach-ers’ reports of learning and application to pedagogy based on engagement in collaborative peer video analysis. Teaching Education, 25(4), 349–374. do i:10.1080/10476210.2014.920001

Christ, T., Arya, P., & Chiu, M. M. (in press). A three-pronged approach to video reflection: Preparing literacy teachers of the future. In E. Ortlieb, L. Shanahan, & M. McVee (Eds.),

Video reflection in literacy teacher education and development: Lessons from research and

practice. Bingley, UK: Emerald. doi:10.1108/

S2048-045820150000005018

Copeland, W. D., & Decker, D. L. (1996). Video cases and the development of meaning making in preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher

Education, 12(5), 467–481.

doi:10.1016/0742-051X(95)00058-R

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (Eds.). (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures

for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks,

TAP (Teacher Learning and Application to Pedagogy) through Digital Video-Mediated Relections

de Mesquita, P. B., Dean, R. F., & Young, B. J. (2010). Making sure what you see is what you get: Digital video technology and the preparation of teachers of elementary science. Contemporary

Issues in Technology & Teacher Education, 10(3),

275–293.

Downey, J. (2008). “It’s not as easy as it looks”: Preservice teachers’ insights about teaching emerging from an innovative assignment in Educational Psychology. Teaching Educational

Psychology, 3(1), 1–13.

Fadde, P., & Sullivan, P. (2013). Using interactive video to develop pre-service teachers’ classroom awareness. Contemporary Issues in Technology

& Teacher Education, 13(2), 156–174.

Goldstein, H. (1995). Multilevel statistical models. London, UK: Edward Arnold.

Greeno, J. G. (2003). Situated research relevant to standards for school mathematics. In J. Kilpatrick, W. G. Martin, & D. Schifter (Eds.), A research companion to principles and standards for school

mathematics (pp. 304–332). Reston, VA: National

Association of Teachers of Mathematics.

Grossman, P., Wineburg, S., & Woolworth, S. (2001). Toward a theory of teacher community.

Teachers College Record, 103(6), 942–1012.

doi:10.1111/0161-4681.00140

Harford, J., & MacRuairc, G. (2008). Engaging student inservice-teachers in meaningful reflec-tive practice. Teaching and Inservice-teacher

Education, 24(7), 1884–1892. doi:10.1016/j.

tate.2008.02.010

Harrison, C., Pead, D., & Sheard, M. (2006). “P, not-P and possibly Q”: Literacy teachers learning from digital representations of the classroom. In M. McKenna, L. Labbo, R. Kieffer, & D. Reink-ing (Eds.), International Handbook of Literacy

and Technology (Vol. 2, pp. 257–272). Mahwah,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Hollingworth, A. (2006). Scene and position specificity in visual memory for objects. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory,

and Cognition, 32(1), 58–69.

doi:10.1037/0278-7393.32.1.58 PMID:16478340

Juzwik, M., Sherry, M., Caughlan, S., Heintz, A., & Borsheim-Black, C. (2012). Supporting dialogi-cally organized instruction in an English teacher preparation program: A video-based, Web 2.0-me-diated response and revision pedagogy. Teachers

College Record, 114(3), 1–42. PMID:24013958

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2008). New learning:

Elements of a science of education. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/ CBO9780511811951

Karppinen, P. (2005). Meaningful learning with digital and online videos: Theoretical perspectives.

AACE Journal, 13(3), 233–250.

Kennedy, P. (2008). Guide to econometrics. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kinzer, C., Cammack, D., Labbo, L., Teale, W., & Sanny, R. (2006). The need to (re)conceptualize preservice teacher development and the role of technology in that development. In M. McKena, L. Labbo, R. Kieffer, & D. Reinking (Eds.), In-ternational handbook of literacy and technology

(pp. 211–233). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Koc, Y., Peker, D., & Osmanoglu, A. (2009). Sup-porting teacher professional development through online video case study discussions: An assem-blage of preservice and inservice teachers and the case teacher. Teaching and Teacher Education,

25(8), 1158–1168. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.020

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social

semi-otic approach to contemporary communication.

London, UK: Routledge.