Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2978180

A Positive Theory of Accounting-Based

Management by Exception

By

Mark Penno

The University of Iowa Tippie College of Business W324 Pappajohn Business Building

Iowa City, IA 52242-1000 USA

May 2017

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2978180

A Positive Theory of Accounting-Based

Management by Exception

ABSTRACT

Management by exception (MBE) is widely used to allocate scarce managerial expertise on the basis of exception reports. I model MBE as a rule that triggers a management intervention if-and-only if accounting thresholds are not met. While the resulting MBE rule economizes on valuable expertise, its mechanical structure creates a mismatch between the rule and the underlying phenomena (i.e., under- and overinclusion). I show that relevant accounting measures are optimally excluded from the exception report as a way to compensate for these mismatches, even when they are costless (violating an informativeness maxim). Furthermore, individual thresholds may not be uniquely determined, clouding the issue of threshold tightness. The model is used to evaluate a number of accounting practices, including management control systems (tightness of standards, moral hazard), auditing independence (waived adjustments), and debt contracting (using covenants as tripwires).

1 1. Introduction

Management by exception (MBE) is used by firms, auditors and private lenders, among others, to simplify the utilization of complex accounting information. In particular, multidimensional accounting data must be grouped and diagnosed before problems can be addressed, and a major purpose of MBE is to efficiently allocate the valuable time spent by the experts who make these evaluations. In his seminal book, Bittel (1964) describes MBE this way (p. 5):

Management by exception, in its simplest form, is a system of identification and communication that signals the manager when attention is required; conversely it remains silent when his attention is not required. The primary purpose of such a system is of course, to simplify the management process itself – to permit a manager to find the problems that need his action …

Accordingly, I model MBE as a two-step process beginning with an exception report that triggers a managerial intervention if and only if its underlying accounting thresholds are not met. While an exception report provides a way to economize on the expertise spent addressing the state of controls, its mechanical structure may result in a mismatch between the if-and-only-if rule governing the report and the underlying phenomena. This mismatch means either that i) an exception report triggers interventions for a state that does not need correction (overinclusion), or ii) that an out-of-control state is ignored (underinclusion). Mismatches have long been of concern to scholars such as Ehrlich and Posner (1974), Simons (1989), Diver (1989), and Sunstein (1995), who discuss the under- and overinclusions of rules.To counter the effects of these mismatches, I demonstrate that certain accounting measures must be optimally excluded from the exception report even when they are informative and costless, and in spite of being given strict consideration when (and if) an intervention is subsequently triggered.

2

not be assigned cost or revenue standards runs contrary to an informativeness maxim holding that otherwise costless and informative measures should be recognized in a formal report.1 Nontrivial

under- and overinclusion helps to explain a literature that has focused on the alleged dysfunctional consequences of budgets.2 And the result that standards may not be uniquely determined in

multidimensional settings with performance evaluation may help to further explain the mixed results from field studies.

A second instance is the practice of using materiality thresholds to identify proposed adjusted journal entries (PAJEs) by external auditors. Because the process is initiated (finalized) by less (more) experienced staff, it may also be regarded as an instance of MBE. For example, Hicks (1964, p. 168) comments:

Materiality at the execution level merits more detailed consideration; here, knowing when to deal with immaterial items is important. Although these decisions are often initially made by staff assistants, they may have significant audit consequences and must be carefully reviewed.

PAJEs are waived at least one-half of the time, and this practice has generated a concern that auditors are rubber-stamping their client’s wishes, indicating a loss of auditor independence.3 The

results here demonstrate, instead, that a cost-efficient auditor will generate more MBE-type

overinclusions, which end up being waived. Noting that incumbent auditors tend to have lower costs, these results are also consistent with empirical findings indicating that proposed audit adjustments are more likely to be waived for clients with whom the audit firm has had a longer relationship (see Section 5). Relatedly, the AICPA (1983, AU 312.02) defines “audit risk”as “the risk that the auditor may unknowingly fail to appropriately modify his opinion on financial statements that are materially misstated.” This study makes notion of ‘unknowingly’ more precise. Simply put, those professionals who are assigned to make final evaluations will not be aware of

1 Decision theory maintains that costless information should not be ignored if it changes beliefs. The term, informative, is frequently associated in the accounting literature with Holmström (1979), who uses it to label a maxim for principal-agent settings.

2 See Hansen and Van der Stede (2004) for a discussion of this focus.

3

an overall material misstatement if the MBE system does not properly alert them to it (underinclusion).

To the extent that the technical defaults triggered by bond covenant violations are threshold-based exceptions, and an expert’s valuable time (in this case, a bank executive) is consumed by default management, conventional debt contracting represents yet another instance of MBE.4 Technical

defaults provide a flow of information to the lender, helping to keep it informed about the status of the loan. Consequently, technical defaults in themselves do not necessarily signify that financial distress is on the horizon (see section 5). That said, covenant tightness has not received extensive attention in the analytical literature,5 and an explanation for why banks waive technical default has

not been fully fleshed out.6 Consistent with empirical findings, this study suggests why waivers of

technical defaults in private lending are common, and why the frequency of waivers may increase with the strength of the lending relationship.

Beyond the specific applications noted above, the study contributes to a conceptual ‘unpacking’ of control systems. For example, Evans and Tucker (2015, p. 347) suggest that:

failing to view control as a package as comprising both formal and informal elements makes it difficult to identify how findings may be integrated and assimilated; how they refute, complement or extend existing theory …

If one were to describe an exception report as a formal component, and management evaluations as a more informal (i.e., a judgement-based assessment) component of a larger management control system, then the finding that relevant measures are sometimes (but not always) excluded from the former but referenced during latter, suggests how accounting measures themselves can

transition between different roles.7

4 In addition to the three applications discussed here, the use of red flags by analysts, regulators and investors constitutes further uses of MBE-style data filters. Furthermore, Hicks (1964) cautions the reader to remember that MBE “is not solely an accounting consideration, as some of the literature on the subject would seem to suggest.” Accordingly, conclusions from this study may be applied to certain non-accounting settings as well.

5 See Gârleanu and Zwiebel (2009). 6 See HassabElnaby (2006).

4

Finally, and most importantly, this study introduces the idea of how if-and-only-if rules serve as the fundamental building blocks for a range of accounting applications, and explains the implications of doing so. This is at odds with the view which casts rules as choice-constraining factors, similar to the conventional income and price constraints found in economics (Vanberg, 1994, p. 15). Under that perspective, it would be irrational to use rules if they restricted one’s choices. In fact, Baiman and Demski (1980a) have proven that a literal application of this view implies, contrary to common practice, that there is no economic demand for variance computations.8 Nonetheless, MBE is remains recognizable as a set of rule-like thresholds; and its

widespread use confirms, contrary to what is generally assumed by standard normative theory, that managerial expertise is not freely available, but rather is a valuable resource to be conserved and allocated.9 Accordingly, this study is positive in nature because it is concerned with the description

and explanation of readily identifiable accounting-based practices.

Section 2 reviews related analytical literature, Section 3 models an MBE rule and Section 4 provides results. Sections 5 and 6 apply and extend the model to the specific accounting practices described above, and Section 7 concludes.

2. Related Analytical Literature

An early approach to accounting-based MBE applies industrial statistical quality control techniques to actual standard cost accounting settings, featuring algorithms which compute numerical limits signaling whether a process is in “in control” or “out of control,”in order to determine when corrections are necessary.10 Kaplan (1975) reviews this literature, but cautions (p.

8 See next section for a discussion.

9 A Google Scholar search (3/1/17) for the joint use of “management by exception,” “simplify” and “accounting,” yielded almost 2,000 results.

10 Attention is directed in these studies to the complexity of proposed algorithms aimed resolving control issues in real-world settings. For example, Dittman and Prakash (1978. p. 25) offer an algorithm for the “practicing

5

312) that in practice, managers rarely use the sophisticated mathematical procedures in specified by these algorithms, and instead use their judgment to determine MBE thresholds, by citing Anthony’s (1973) review article, who notes that “few if any managers believe that statistical techniques … are worth the effort to calculate [cost standards].” Kaplan (p. 312) further suggests that exception report be simple in the following manner:

There are reasons to believe, however, that some form of screening model would be beneficial to managers by eliminating the need for them to examine extensive variance reports item by item in order to detect a significant variance.

The model presented here captures Kaplan’s stated view by representing an exception report as a binary indicator that simply flags whether or not an intervention is called for.

Holmstöm (1979) demonstrates that as long as information is costless, any marginally informative measure will benefit a principal when contracting with a risk-averse and self-interested agent. Similarly, a fundamental implication of decision theory (for cases where moral hazard is absent) is that marginally informative data will improve decisions, as well. Holmstöm (p. 86) warns, however, that:

If, for administrative reasons, one has restricted attention a priori to a limited class of contracts (e.g., linear price functions or instruction-like step-functions), then informativeness may not be sufficient for improvements within this class.

Similarly, this study examines the effect of the administrative restrictions placed on the use of accounting information by MBE filters, and confirms that a measure’s relevance11 may not be

sufficient for improvements – even when that information is costless.

Baiman and Demski (1980a) refine Holmstöm’s normative model to implicitly demonstrate (Proposition 1.1) that there will be no economic demand for the computations that give rise to

6

variances.12 Baiman and Demski (1980a, 1980b) go on to define variance investigation more

narrowly by modeling a setting where a principal designs a contract for a self-interested agent based on a costless primary performance measure plus a costly second measure produced conditionally upon the realization of the first measure. The ‘investigation’ studied by these authors differs from the ‘intervention’ examined here in that the purpose of an investigation is not to correct any out-of-control states, but rather the threat of a conditional investigation is used to improve on

ex ante managerial incentives. An important finding for this type of model is that realizations of the primary measure found in the tails of the distribution may not always trigger an investigation, and that the results are sensitive to the agent’s utility function and the probability distribution assumed by the model.13 Consequently the explanatory power of this approach is limited to the

extent that, unlike MBE practice, the model does not necessarily single out exceptional

observations for investigation.

Similar to this study, Garicano (2000) models an organizational hierarchy that specifies a handful of knowledgeable individuals at its top and less knowledgeable members at its bottom. For this setting, he shows that it is optimal for the knowledge of solutions to the most common or easiest problems to be located on the production floor, whereas the knowledge about how to solve more exceptional or harder problems is located in higher layers of the hierarchy. This result requires an information system that is capable of distinguishing exceptional from common problems, thereby establishing a rationale for a management by exception policy. The study here is similar to Garicano’s in that I assume the need for experts, but differs by identifying a readily recognizable report structure specifically designed to minimize the expected sum of intervention costs and the costs of not correcting out-of-control states.14

12 Suppose that

q1, q2

reflects a computation based on accounting measures q1 and q2. Then Baiman and Demski note that any contract of the form s

q1,q2,

q1,q2

can be replaced by an equivalent contract s

q1, q2

without the need for, where s

q1, q2

s

q1,q2,

q1,q2

. The reasoning may be then extended to any decision d

q1,q2,

q1,q2

.13 For example, Lambert (1985) shows that in general, neither the extremeness nor the unusualness of the cash flows provides a measure of the benefits of conducting an investigation. Also see Young (1986) for an analysis of two tailed requirements.

7 3. Basic Model

The accounting system produces two measures, q1 and q2, where

q1, q2

is the realization of a random variable that is uniformly distributed over the unit square. The exception report is based on these measures, but indicates only whether or not a managerial intervention will be called for (i.e., its report is binary). The exception report calls for an intervention by an expert evaluator if-and-only-if q1 t1 or q2 t2,where t1 and t2 are the thresholds underlying the exception report. The expert’s specialized knowledge is summarized by

,k , which along with

q1, q2

is used by the expert to determine whether the state is in control. The state is in control when q1q2 k,and out of control when q1q2 k. Assume that 0k1 and 01.15

Without an intervention, the firm has a net payoff, q1q2 k. If we view q1q2 k0 as the ‘damage’ caused by being out of control, then I assume that an intervention allows the organization to mitigate that damage by ex post resetting any net loss to zero. Let c0 represent the cost of the evaluator’s time spent in assessing, and resetting if necessary, the state of control. Then given an intervention, the organization’s payoff is q1q2kc if the state is in control,

and c if the state is out of control and then corrected. The following summarizes the net payoff to the organization for each possible event:

Note that the model assumes that an intervention provides an incremental benefit (eliminating a loss) only when the state is sufficiently unfavorable, thereby assigning a trouble-shooter’s role to

15 Assuming that k1 limits the number of required the geometric representations (e.g., Figure 1 below).

Event Net payoff

The expert intervenes and q1q2 k c

The expert intervenes and q1q2 k q1q2 kc

8

the evaluator. This assumption is reflected in descriptions of MBE practice. For example, Kohler (1975, p. 301), in A Dictionary for Accountants: Fifth Edition, asserts that

these [exception] reports bring out “favorable” and “unfavorable” variances, the latter being the basis for “management by exception.”

Similarly Brownell (1983, p. 456) observes that MBE practice reduces to “a preoccupation with unfavorable variances,” and more recently, Arnold and Artz (2015, p. 66), also conclude that academic field studies tend to focus on unfavorable variances as well.

Figure 1 summarizes an MBE rule.

--Place Figure 1 about here--

The diagonal line maps the

q1, q2

pairs such that q1q2 k, and defines the boundary between being in control and being out of control. This boundary captures the pattern of classifications that an expert with knowledge of k and would make based on available evidence, q1 and q2. If, instead, the organization had a costless algorithm which could analyze

q1, q2

based on k and ,that generates understandable instructions for lower level personnel or machines, then there would be no economic demand for MBE. Consequently, a sufficient condition for a strict demand for MBE is that an automated self-correcting process not exist, or that management must be personally involved to identify and reset out-of-control processes (as required by MBE).

Outcomes above the diagonal represent in-control states which will not benefit from correction, while those below the diagonal represent outcomes that will benefit from correction. The diagonal’s slope expresses the interaction between q1 and q2. Note that because

q1, q2

is uniformly distributed on the unit square, the area corresponding to a particular event also represents the probability of that event. The dotted areas (both light and dark together) represent those outcomes that will not be evaluated, with an ex ante probability (area) ANE=

1t1 1t2 ,9

q1, q2

conditioned on an out-of-control state not being evaluated and corrected is the centroid ofthe dark dotted triangle, or

NC NC

Which, in turn, implies that the expected loss of not correcting a state that is out of control is:

1 2

[MBE’s] big advantage lies in the fact that much of the time-consuming process of thinking and decision making can be done in advance.

Accordingly, I assume that the MBE rule is designed by an expert (again a member of management) who understands AE, ANCand ENC as described above and chooses t1 and t2 to minimize the overall expected loss associated with investigations and underinclusions, which is the expected sum of intervention costs and the costs of not correcting out-of-control states

10

where the minimization of (1) approximates the exercise of an expert’s intuition.17

4. Results

As a useful benchmark, Figure 2 depicts a rule where t1 0. When t1 0,threshold t2 alone dictates whether an intervention will be called for by the exception report, which is equivalent to saying that t1 has been omitted from the exception report.

--Place Figure 2 about here--

Proposition 1a (Case 1) below indicates that as long as k1, then the optimal t1 0,

regardless of c . In particular, as long as the importance of q1 is sufficiently low (as reflected by a small ) or the ex ante likelihood that the state is an in-control state is sufficiently high (as reflected by a small k), then a threshold for q1 will not be specified in the exception report, and

1

q is not needed. This proves that whether a relevant measure is included in the exception report is not dictated by the cost of the intervention alone, but is also due to the under- and overinclusion effects of the MBE rule itself. While omitted from the exception report, q1 continues to be relied upon by the evaluator (as long as 0) for making control classifications whenever an intervention is called for (q2 t2).

Proposition 1a:

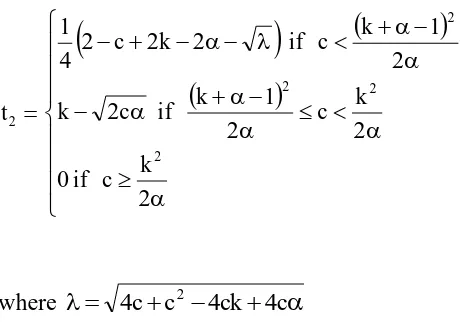

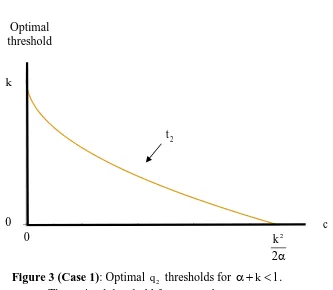

Case 1: If k1, then the optimal t10 and

11

Optimal t2 thresholds for Case 1 are illustrated by Figure 3:

--Place Figure 3 about here--

MBE ceases to provide a net benefit to the organization when t2 0, or c exceeds

interventions do not occur because they are too expensive.18

Next, consider the Case 2 where k1, and Figure 1 applies:

12

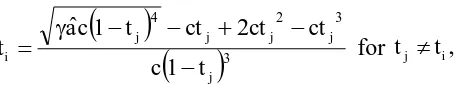

Optimal thresholds for Case 2 are illustrated by Figure 4:

--Place Figure 4 about here--

Figure 4 shows how the cost of a managerial intervention affects whether an accounting measure will be included in the exception report. Because, by assumption, 1; measure q1 is dropped first (t10) as c increases, eventually followed by dropping q2 (t2 0). Again, if both thresholds equal zero, then MBE ceases to provide a net benefit.

Corollary 1: When 0,then the optimal

t1,t2 is located strictly below the diagonalk q

q

1 2 .

13

Next note that Figure 4 depicts thresholds that are declining in c More generally, .

Corollary 2 (Slack): The optimal thresholds, t1 and t2 are decreasing in c .

Declining thresholds reflect an increase in overall (budgetary) slack, and Corollary 2 provides the intuitive result that slack increases as the cost of managerial intervention increases.

A waiver occurs when the expert determines that an exception is actually an overinclusion. Figure 1 depicts a scenario where an exception is waived whenever

q1, q2

lies within one of the polygons with checkered fill. Note from Corollary 2 that both optimal thresholds are decreasing in c . Imagine decreasing t1 and/or t2 while holding k constant. Then, by inspection of Figure 1, it is clear that the area devoted to waivers decreases as t1 and/or t2 decrease (and c increases).Corollary 3 (Waivers): The probability of a waiver increases as c decreases.

Given the informational constraints imposed by the MBE filter, the organization insures itself against uncorrected out of control states by increasing the probability of waivers, which in turn, decreases the probability of a missed out of control state (underinclusion).

Corollaries 2 and 3 together summarize the role of c in determining how the MBE rule functions. To the extent that a lower value of c indicates more efficient interventions, a lower value of c represents a higher level of managerial expertise. This observation is useful in discussing applications of the model to specific accounting settings in Section 5.

5. Applications and Extensions

14

Because external auditors use materiality thresholds to identify proposed adjusted journal entries (PAJEs), excessive waivers of PAJEs may create the impression that the auditor’s independence has been impaired. For example, Coffee (2001, p. 23) suggests that:

auditors often are aware that earnings management is being attempted, but nonetheless waive any audit adjustment on a variety of grounds, including the practice’s asserted immateriality…

Alternatively, Braverman et al. (1997) suggest the auditor’s impairment may be an unconscious one, by proposing a less-than-noticeable differences explanation, where auditors’ judgment is gradually captured by their clients’ wishes.

It turns out that waivers of PAJEs are quite common. Houghton and Fogarty (1991) and Wright and Wright (1997) separately find that auditors waive 65 to 75 percent of all audit detected misstatements, whereas Icerman and Hillison (1991) find that auditors waive approximately one-half of detected errors. To reconsider the issue of PAJEs, suppose that t1 and t2 represent individual materiality thresholds. To remain consistent with the model, suppose that the cumulative misstatement is decreasing in q1q2, and k represents the allowable cumulative misstatement such that q1q2 k is not materially misstated. This relation would hold, for example, if understatements of total expense were the investors’ concern. A decreasing relation might also be expected where q1q2 represents an auditor’s assessment of company-wide internal control, which the auditor issues in a separate report.19

Consider a modification of (1), and restate the auditor’s objective as

NC NC

Ec A E

A , (5)

15

where the first component represents the expected direct cost of a review, and parameter now scales the expected loss borne when the auditor unknowingly fails to modify its opinion given an underlying misstatement.20 Define c by

c

c .

The expression, AEcANCENC, has the same minimum as (5), and has the same form as (1), with the exception that c replaces c. Consequently, we may apply the results previously derived for (1). In particular, increasing has the same general effect as decreasing c. Consequently, increasing increases the probability of a waiver (Corollary 3).

If the regulator’s concern were to stem from the frequency of waivers in the first place, then increasing the auditor’s general liability for ignoring material errors, , could backfire – if the regulator responds to concerns about auditor independence by increasing , then the imposition of regulation increases the probability of a waiver even more, potentially prompting a repeated regulatory action. If, on the other hand, the frequency of waivers, itself, were used by the regulator to target penalties, then the optimal MBE policy will be compromised if auditors adjust (i.e., relax) their thresholds in order to reduce the frequency of waivers (overinclusions) and with the goal of classifying fewer items as PAJEs. (See Figure 1). This would then increase audit risk (the dark dotted area) – which was the regulator’s ultimate concern to begin with. In summary, by giving in to political and other pressures by treating outward symptoms with coarse responses, the regulator could actually worsen audit quality.

Corollary 3 also implies that an incumbent auditor will generate more waivers than a new auditor who is at the beginning of its learning curve, and for whom the cost of an intervention will be higher.21 Joe et al. (2011) confirm this conjecture by finding that PAJEs are more likely to be

20 AICPA (1983, AU 312.02).

16

waived for clients with whom the audit firm has had a longer relationship, but conclude that the pattern does not reflect favoring such clients. Similarly, the model provides an explanation against the charge that auditors intentionally give in to clients from whom they extract quasi-rents.22

Debt Covenants

Debt covenants frequently contain thresholds that trigger technical defaults.23 Dichev and Skinner

(2002) argue that private lenders set debt covenants tightly and use them as “trip wires” for borrowers. While empirical work has begun to examine the corresponding tightness of accounting-based thresholds,24 the rationale for how and why these trip wires are set is not well understood.

Furthermore, technical defaults are frequently waived. For example, Beneish and Press (1995, p. 346) indicate that 51% of their default firms reported waivers. To that end, the model here provides a simple rule-based explanation of why a lender would go through the trouble of designing accounting-based thresholds, only to waive technical defaults.25

To apply the model, let q1q2 represent the expected cash flow available to pay off the debt, k,

and k

q1q2

0 the expected loss incurred conditioned on an cash shortfall.26 Suppose thatupon technical default, the lender waives technical defaults for otherwise profitable loans, and restructures unprofitable loans to restore the expected cash flow back to k If we assume that the . net cost of investigating/resolving a technical default is c then the MBE model applies. ,

22 See Magee and Tseng (1990). Levitt (1998) suggests that “auditors who want to retain their clients are under pressure not to stand in the way.”

23 The thresholds discussed here are affirmative covenants which require borrowers to maintain specified levels of accounting-based ratios. Smith (1993) notes that extant evidence suggests that borrowers more frequently violate affirmative covenants. The breach of negative covenants (which limit certain investment and financing activities) is rare.

24 See for example, Demiroglu and James, (2010), or Demerjian and Owens (2016). Demerjian and Owens note that while many studies refer financial covenant “slack,” “tightness,” or “strictness,” they prefer the term “probability of violation.”

25It is notable that the common usage of the term, technical, suggests a faulty assessment, and referring to a default as ‘technical’ serves to downplay the event. For example, Merriam Webster (online) describes ‘technicality’ as “a small detail in a rule, law, etc., and especially one that forces an unwanted or unexpected result.” (Emphasis added.) See http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/technicality

17

Corollary 3 indicates that the probability of a waiver is highest when c is low. To the extent that relationship banking lowers the cost of intervention, we might expect waivers to be common in private debt. In that regard, Gopalakrishnan and Parkash’s (1995) survey indicates private contains more restrictive debt covenants than public debt. If lenders learn more about borrowers over time, we might also expect waivers to increase with the length of the borrower-lender relationship as c

declines. This is consistent with HassabElnaby (2006) who finds that strong bank-firm business ties are more likely to be associated with a higher level of waivers.

6. Moral Hazard (Management Control Systems)

Hopwood (1972, p. 158) suggests that because organizations require their accounting reports to address multiple issues, they may end up failing to address any specific issue very well:

accounting systems are also trying to serve many purposes. … However, in trying to satisfy a series of purposes, the reports may fail to perfectly satisfy the requirements for any single purpose – the appraisal of managerial performance, for instance.

To examine the question of performance, and in particular, the role of incentives, this section extends the model to include moral hazard. The extension indicates that an exception report with moral hazard may look quite different than one without moral hazard. In particular, the mixed findings from field studies are consistent with the result that thresholds may no longer be uniquely determined when moral hazard is present.27

As before, the exception report is based on q1

0,1 and q2

0,1 where

q1,q2

is uniformly distributed over the unit square. The extension assumes that a risk-neutral agent’s effort directly contributes to control, but that it is not directly measured. Let a

0,aˆ represent a risk-neutral

18

agent’s effort choice, for which the agent suffers disutility a, where aˆ0 and 0. The state is now considered to be in control if q1q2 a k and out-of-control if q1q2ak. In this extension, the evaluator observes the state of control (the sum), q1q2a, which along with

,

1

q q2 and knowledge of , permits the evaluator to infer a If the evaluator infers that . aaˆ (work), then the agent receives the bonus, B. If the evaluator infers that a0 (shirk), then the agent receives no bonus. If an intervention is not performed (there is no evidence to indicate that the agent did not work), I assume that the agent receives bonus, B. Consequently, the compensation arrangement ensures that an agent who works obtains the bonus.

The agent considers the consequences of working and shirking before deciding what to do. An agent who works has utility Baˆ, while an agent who shirks receives no bonus with probability

1 1

1 2

1 t t , (9)

and will have an expected utility of

1t1

1t2

B. Assume that the agent has an opportunity utility of zero. Then the agent will work for this organization if Baˆ

1t1

1t2

B, or:2 1 2 1

ˆ

t t t t

a B

. (10)

If the organization were to prefer that a 0, then there is no need to incentivize

B0

, and the model and results from Section 3 apply. Accordingly,I assume that the organization wishes the agent to work and provides the incentive to do so. This implies that if the organization wishes to minimize expects costs, then (10) is an equality.28 Then the right-hand side of (10) decreases ineither t1 or t2, which means that tighter thresholds require lower bonuses, but more costly intervention. Because the organization wishes to motivate effort, one would expect tighter thresholds than were indicated in the previous sections.

28 If ˆ ,

2 1 2 1 t tt

t a B

then the organization is not minimizing expected costs. Because t1 t2 t1t2 1,we

19

Given that incentives are in place for the agent to choose aˆ, the following represents the net payoff to the organization of each possible event:

See Figure 5.

--Place Figure 5 about here--

Because kˆkaˆ effectively determines the

q1, q2

demarcated boundary between in-controland out-of-control,29 let

NC

Aˆ and EˆNCequal the analogs of ANC and ENCgiven that kˆkaˆ replaces k in the respective expressions. Then the organization’s expected cost equals

Both (11a) and (11b) imply that the agent works and is (always) paid B , but (11b) also indicates that when t1t2ak (see Figure 5), there are no cases where an out-of-control state is ignored

(underinclusions) , and the expected cost associated with ignoring out-of-control cases, AˆNCEˆNC, drops out of the analysis.

20

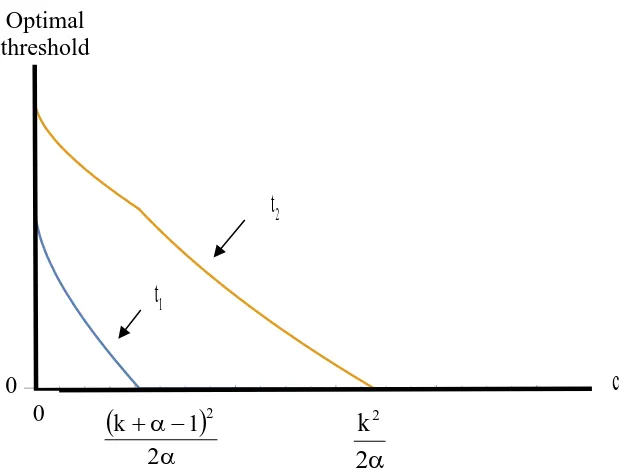

Figure 5 differs from Figure 1 in that

t1,t2 is now located above the boundary for in-control and out-of-control, rather than below the boundary (as previously established by Corollary 1). This will occur when moral hazard becomes a sufficiently prominent factor. This guarantees that all out-of-control states will be corrected as a consequence of the organization’s incentive-related vigilance.30That is, addressing one problem may automatically solve the other. Also note that once an optimal threshold pair is located above the diagonal, numerous threshold combinations will be optimal as long as the threshold pairs provide the same probability (and expected cost) of intervention. In that case, the optimal

t1,t2 is not unique, and Proposition 2 indicates when this happens:Proposition 2 (Moral Hazard): Suppose that the organization prefers that the agent work.31 If

k

and the optimal probability of intervention,

1 1

1 2

1 t t (13)

is unique and decreasing in c .

21 Example 1 illustrates a case where k

c

aˆ ˆ

. In particular, it demonstrates that when 0,

1

q

may be optimally included in the exception report, even though it is irrelevant to assessing the state of controls.

Example 1: Suppose that 0, c .3, .2, k1, aˆ .5 and kˆ.5. Then both

t1,t2 0, .58

and

t1,t2 .1, .53

are optimal, the probability of intervention is .58, the bonus payment equals .17, and the expected intervention cost equals .17.It may at first appear that MBE could be simply replaced by random check whether the agent worked, done with probability p, where p1

1t1 1t2

.58. This policy of random checking would maintain the incentive to work without changing the bonus, but using MBE to link the interventions to accounting outcomes also guarantees that the state is always corrected when necessary. This benefit would be lost by pure randomization. Thus, the control issue is still indirectly addressed by employing MBE with even a seemingly irrelevant threshold, and we see that the addition of moral hazard has dramatically changed the way that we describe the operation of MBE.Example 2 continues Example 1 by reducing the agent’s disutility, from .2 to .15,so that k

c

a ˆ

5 .

ˆ

. In this case there is for only one solution to be optimal.

Example 2: Suppose that 0, c.3, .15, k1, aˆ.5 and kˆ.5. Then the unique optimal

t1,t2 0,.5 , the probability of intervention is .5, the bonus payment equals .15, and the expected intervention cost equals .15.22

characterized by frequent personal attention from top management levels.32 A diagnostic style

might apply to the settings examined in the previous sections, while an interactive style may be motivated by concern for moral hazard.

7. Conclusions

Management by exception (MBE) is widely used to allocate scarce managerial expertise on the basis of exception reports. The model provides a novel and coherent view of MBE by reducing it to a small, yet salient, set of factors which explore the fundamental rule-like nature of an exception report.33 In particular, the study demonstrates how alleged dysfunctions of accounting practice

might be simply explained as under- or overinclusions. While these mismatches may be ex post

inefficient , they are optimal, ex ante. The model provides insight into a number of specific accounting-based applications which, in turn, constitute a subset of a larger set of accounting practices.34 As Holmström (1979) has indicated, administrative realities may entail a violation of

an informativeness maxim. Because MBE filters information, it constrains how that information is used. In some cases, relevant measures may be excluded from exception reports; and in other cases, irrelevant measures may be included in the exception report.

As a final note, Gjesdal (1981) makes the distinction between accounting information as used for investment decisions and accounting information as used for stewardship. This study suggests even finer distinctions. When restricted to stewardship itself, the use to which accounting information is put depends on whether its main purpose is to control moral hazard or to address the expected cost of managerial interventions, and addressing one problem may automatically resolve the other.

32 See Shen and Perera (2012) for a review of the accounting literature on the diagnostic and interactive uses of budgets.

33 Contrast this to Fisher (1995, p. 24) who notes that “one of the major weaknesses of contingent control research [a dominant method for organizing field studies] is the piecemeal way in which it is done.”

23 Appendix

Lemma 0: The optimal

t1,t2 is located weakly below the diagonal, or t1t2 k.Proof: If instead, the optimal

t1,t2 were located above the diagonal, the organization could general an expected cost savings (intervention) by reducing

t1,t2 so that t1t2 k.Proof of Proposition 1:

Proof : Objective function (1) equals

� −� � − � − �� � + �� −� − � � −�+� − �� − �+� + �−� � +�

6� . (A1)

(A1) is convex in t1 for a given t2 whenever t1t2 k, and (A1) is convex in t2 for a given t1 whenever t1t2 k, with strict convexity following from strict inequalities. Assume that the

organization picks one threshold first and then the other one second. Lemma 0 ensures that

t1,t2is a minimum. Corollary 1 (below) shows that for 0, kt1t2 holds for the optimal

t1,t2pair, which means that the optimal

t1,t2 will be unique.I will represent the optimal thresholds by their first-order conditions. The first-order condition of (A1) with respect to t1 is:

� =

��−�� −√ √�� −�� �� . (A2)Insert (A2) back into (A1) to find that the first-order condition of (A1) with respect to t2 is:

� = 2 − � + 2� − 2� − √4� + � − 4�� + 4�� . (A3)

Insert (A3) back into (A2) to get

1

t � +� − +�+ �+√� +�− �+ � − √ √�� +�− �+ �+√� +�− �+ �

� . (A4)

It can be verified that (A4) is declining in c , and equals zero whenever

2

12

k

c and is

negative whenever

, 212 k

c or we have a corner solution (t1 0) whenever

2

12

k

24 In this case (t1 0), condition (A1) reduces to

� − � − �� � + �� −�

6� . (A6)

And the first order condition with respect to t2 equals

k c

t2 2 , (A7)

which is less than one, declining in c , and equals zero (corner solution) when . 2

Proposition 1 for . 2

Proof of Corollary 3: By inspection of Figure 1.

Proof of Proposition 2: The proof proceeds by first demonstrating four lemmas.

25 and the resulting t1M t2M kaˆ, then

M M

t

t1 , 2 minimizes the overall organization’s expected

cost, (11a)-(11b).

Then it immediately follows

overall objective function, (11a)-(11b), as well.

Lemma 2: The first-order conditions for a

t1,t2 pair that minimizes (A8)26

Lemma 3: If

t1', t2' and

t1'', t2'' both minimize (A8) then

1t1' 1t2' 1t1'' 1t2'' , or one minus the probability of intervention is identical. Furthermore this probability is increasing in c .Proof: Suppose that t1 obeys (A9a) and t2 obeys (A9b). Then

1t1

1t2

equalsThe derivatives of (A10) and (A11) with respect to t2 and t1respectively are zero, which means that the probability of intervention is constant for all values of (A9a) and (A9b). The derivatives

of these (A8) and (A10) with respect to c are √��� − +�

Lemmas 1-4 collectively prove Proposition 2.

27

Example 1: If the agent is incentivized to work, then B.17, and the expected profit equals

035 . 17 . 17 . 75 . 5

. . If the agent not incentivized, then B0, Proposition 1a holds,

, 1

2 k

t and the expected payoff equals 0.3.3, meaning that organization would prefer

that the agent work. Also note that ˆ .58kˆ.5

c a

Example 2: If the agent is incentivized to work, then B.15, and the expected profit equals

. 075 . 15 . 3 . 58 . 75 . 5

. If the agent not incentivized, then B0, Proposition 1a holds,

1

2 k

t , and the expected payoff equals 0.3.3, meaning that the organization would prefer

that the agent work. Also note k c

a ˆ

5 .

ˆ .

Demonstration that the solution for Example 2 is unique: See Figure 6.

--Place Figure 6 about here--

28 0

0

1 1

1

t

2

t

1

q

1

q k

t2

k

1

t k

Figure 1: A formal MBE rule for k (top) and k(bottom)

No intervention Waiver

A diagonal line indicates

q1, q2

pairs which result in k.Out of control, but no intervention 0

0

1 1

1

t

2

t

2

q

1

q

1

q k

t2

k

1

t k

2

q

k

29 0

1 1

0 2 t

2 q

1 q

1 q k

t2

k

No intervention Waiver

Figure 2: A formal MBE rule with t10 and k.

Out of control, but no intervention

The diagonal line indicates q1, q2 pairs which result in k.

30

0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8

0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6

Optimal threshold

Figure 3 (Case 1): Optimal q2 thresholds for k1. The optimal threshold for q1 equals zero.

2

t

c

2 2

k

0 0

31

0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6

Optimal threshold

Figure 4 (Case 2): Optimal Thresholds for k1.

1

t

2

t

c

0

0

2 12

k

2

2

32 0

0

1 1

Figure 5: An instance of a formal MBE rule with moral hazard. The diagonal line indicates

q1, q2

pairs such that q1q2 aˆk.2

q

2

q

1

)

ˆ

(

k

a

q

2

t

1

33

1

Figure 6: This figure verifies that the solution for Example 2 is unique. The three dots illustrate

t1,t2 combinations all of which result in the same probability ofinvestigation, but only one of which is optimal.

2

q

2

q

1

)

ˆ

(

k

a

q

0 0 Inadmissible

Optimal

34 References

American Institute Of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), 1983, Audit Risk and Materiality in Conducting an Audit. Statement on Auditing Standards No. 47, New York: AICPA, 1983.

Anthony, Robert, 1973, Some Fruitful Directions for Research in Management Accounting. In Nicholas Dopuch and Lawrence Revsine (Eds.), Accounting Research 1960-1970: A Critical Evaluation. Champaign, IL: Center for International Education and Research in Accounting at the University of Illinois.

Arnold, Markus and Martin Artz, 2015, Target Difficulty, Target Flexibility, and Firm

Performance: Evidence from Business Units’ Targets, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 40, pp. 61–77.

Baiman, Stanley and Joel Demski, 1980a, Economically Optimal Performance Evaluation and Control Systems, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 18, pp. 184-220.

Baiman, Stanley and Joel Demski, 1980b, Variance Analysis Procedures as Motivational Devices, Management Science, Vol. 26, pp. 840-848.

Bazerman, Max, Kimberly Morgan and George Loewenstein, 1997, Opinion: The Impossibility of Auditor Independence, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 38, pp. 89-94.

Bedford, David, Teemu Malmi, and Mikko Sandelin, 2016, Management Control Effectiveness and Strategy: An Empirical Analysis of Packages and Systems, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 51, pp. 12-28.

Beneish, Messod and Eric Press, 1995, The Resolution of Technical Default, The Accounting Review, Vol. 70, pp. 337-353.

Birnberg, Jacob, And Raghu Nath, 1967, Implications of Behavioral Science for Managerial Accounting, The Accounting Review, Vol. 42, pp. 468-479.

Bittel, Lester, 1964, Management By Exception: A Systematizing and Simplifying of the Managerial Job, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Brownell, Peter, 1983, The Motivational Impact of Management-By-Exception in a Budgetary Context, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 21, pp. 456-472.

Chenhall, Robert. 2003, Management Control Systems Design within its Organizational Context: Findings from Contingency-based Research and Directions for the Future, Accounting,

35

Coffee, John, 2001, The Acquiescent Gatekeeper: Reputational Intermediaries, Auditor

Independence, and the Governance Of Accounting. Working paper, Columbia University School, SSRN.

DeAngelo, Linda, 1981, Auditor Independence, ‘Low Balling’, and Disclosure Regulation,

Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 3, pp. 113-127.

Demerjian, Peter, 2011, Accounting Standards and Debt Covenants: Has the “Balance Sheet Approach” Led to a Decline in the use of Balance Sheet Covenants?, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 52, pp. 178-202.

Demerjian, Peter and Edward Owens, 2016, Measuring the Probability of Financial Covenant Violation in Private Debt Contracts,Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 61, pp. 433-447.

Demiroglu, Cem and Christopher James, 2010, The Information Content of Bank Loan Covenants, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 23, pp. 3700-3737.

Dichev, Ilia and Douglas Skinner, 2002, Large–Sample Evidence on the Debt Covenant Hypothesis, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 40, pp. 1091-1123

Dittman, David and Prem Prakash, 1978, Cost Variance Investigation: Markovian Control of Markov Processes, Journal of Accounting Research, pp. 14-25.

Diver, Colin, 1989, Regulatory Precision, in Making Regulatory Policy, edited by Keith Hawkins and John Thomas, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Ehrlich, Isaac and Richard Posner, 1974, An Economic Analysis of Rules, The Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 3, pp. 257-286.

Evans, Mark and Basil Tucker, 2015, Unpacking the Package: Management Control in an Environment of Organisational Change, Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management, Vol. 12, pp. 346-376.

FASB, 2008, Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2: Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information, Norwalk CT, Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Fisher, Joseph, 1995, Contingency-Based Research on Management Control Systems:

Categorization by Level of Complexity, Journal of Accounting Literature, Vol. 14, pp. 24-53.

Garicano, Luis, 2000, Hierarchies and the Organization of Knowledge in Production, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 108, pp. 874-904.

36

Gjesdal, Frøystein, 1981, Accounting for Stewardship, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 19, pp. 208-231.

Gopalakrishnan, V. and Mohinder Prakash, 1995, Borrower and Lender Perceptions of

Accounting Information in Corporate Lending Agreements, Accounting Horizons, Vol. 9, pp. 13-26.

Hansen, Stephen and Wim Van der Stede, 2004, Multiple Facets of Budgeting: An Exploratory Analysis, Management Accounting Research. Vol. 15. pp. 415–439.

HassabElnaby, Hassan, 2006, Waiving Technical Default: The Role of Agency Costs and Bank Regulations, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, Vol. 33, pp. 1368-1389.

Hicks, Ernest, 1964, Materiality, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 2, pp. 158-171.

Hogarth, Robin, 2001, Educating Intuition, University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

Holmstöm, Bengt, 1979, Moral Hazard and Observability, Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. 10, pp. 74-91.

Hopwood, Anthony, 1972, An Empirical Study of the Role of Accounting Data in Performance Evaluation, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 10, pp. 156–182.

Houghton, Clarence and John Fogarty, 1991, Inherent Risk, Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, Vol. 18, pp. 87-108.

Icerman, Rhoda and William Hillison,1991, Disposition of Audit-Detected Errors: Some Evidence on Evaluative Materiality, Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, Vol. 10, pp. 22–34.

Joe, Jennifer, Arnold Wright, and Sally Wright, 2011, The Impact of Client and Misstatement Characteristics on the Disposition of Proposed Audit Adjustments, Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, Vol. 30, pp. 103-124.

Kaplan, Robert, 1975, The Significance and Investigation of Cost Variances: Survey and Extensions, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 13, pp. 311-337.

Kohler, Eric, 1975, A Dictionary for Accountants: Fifth Edition, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lambert, Richard, 1985, Variance Investigations in Agency Settings, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 23, pp. 533-647.

37

Levitt, Arthur, 1998, The Numbers Game: Remarks by Arthur Levitt, Securities and Exchange Commission, NYU Center for Law and Business. Accessed 5/14/20157 at

https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/speecharchive/1998/spch220.txt

Magee, Robert and Mei-Chung Tseng, Audit Pricing and Independence, The Accounting Review,

Vol. 65, pp. 315-336.

Merchant, Kenneth and Jean-François Manzoni, 1989, The Achievability of Budget Targets in Profit Centers: A Field Study, The Accounting Review, Vol. 64, pp. 539-558.

Messier, William, Nonna Martinov-Bennie and Aasmund Eilifsen, 2005, A Review and Integration of Empirical Research on Materiality, Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, Vol. 24, pp. 153-187.

Shen, Sabrina And Sujatha Perera, 2012, Diagnostic and Interactive Uses of Budgets and the Moderating Effect of Strategic Uncertainty, Asia-Pacific Management Accounting Journal, Vol. 7, pp. 127-155.

Shields, Michael, 1983, Effects of Information Supply and Demand on Judgment Accuracy: Evidence from Corporate Managers, The Accounting Review, Vol. 58, pp. 284-303.

Simons, Kenneth, 1989, Overinclusion and Underinclusion: A New Model, UCLA Law Review, Vol. 36, pp. 448-528.

Simons, Robert, 1988, Analysis of the Organizational Characteristics Related to Tight Budget Goals, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 5, pp. 267-283.

Simons, Robert, 1991, Strategic Orientation and Top Management Attention to Control Systems.

Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12, pp. 49–62.

Smith, Clifford, 1993, A Perspective on Accounting-Based Debt Covenant Violations, The Accounting Review, Vol. 68, pp. 289-303.

Sunstein, Cass, 1995, Problems with Rules, California Law Review, Vo. 83, pp. 953-1026.

Vanberg, Victor, 1994, Rules and Choice in Economics, Routledge: New York.

Weiss, Dan, 2014, Internal Controls in Family Owned Firms. European Accounting Review, Vol. 23, pp. 463-482.

38