11 Years of Age

Naomi Breslau and Howard D. Chilcoat

Background: We examined the relationship between low birth weight (LBW) and psychiatric problems at age 11 years.

Methods: Random samples of 6-year-old LBW and nor-mal birth weight (NBW) children from two socioeconom-ically disparate communities were identified, traced, and assessed. We targeted the 1983–1985 cohort of newborns who reached age 6 in 1990 –1992, the scheduled period of fieldwork. Of the 1,095 in the target sample, 823 (75%) were assessed. Five years later, the sample was reas-sessed. Behavior problems were evaluated by standard-ized behavior problems scales rated by mothers and teachers. A multiple regression application that combines data from multiple informants was used. Prospective data were used to estimate the incidence of severe attention problems during the follow-up period.

Results: Information from mothers and teachers revealed that LBW was associated with an excess of attention problems at age 11 in the urban but not in the suburban children. In the urban setting, LBW children had a higher incidence of clinically significant attention problems than NBW children. Although LBW children scored higher than NBW children on externalizing problems, the effect was accounted for in large part by maternal smoking in pregnancy.

Conclusions: The LBW-attention problems association observed in the urban community suggests an interaction between biologic vulnerability associated with premature birth and environmental risk associated with social disad-vantage. Further research and replication are called for.

Biol Psychiatry 2000;47:1005–1011 © 2000 Society of

Biological Psychiatry

Key Words: Low birth weight, attention problems, urban

versus suburban

Introduction

L

ow birth weight (LBW) serves as a marker for defining high-risk newborns, as it is correlated with prenatal risk factors, intrapartum complications, and neo-natal disease, and is comprised primarily of premature births. The commonly used definition of 2500 g for LBW provides striking contrasts in mortality and morbidity, although a relationship with some outcomes can be ob-served up to 3500 to 4000 g (Kleinman 1992). The improved survival of LBW infants has provided a com-pelling rationale for continued research into later develop-ment of LBW children.With few exceptions, recent studies on the long-term neuropsychiatric sequelae of LBW have focused on the extreme low end of the birth weight distribution, that is, very low birth weight (#1500 g) or extremely low birth weight (#1000 or even#750 g). Very low birth weight (VLBW) is associated with high rates of peri- or intraven-tricular hemorrhage, severe respiratory distress syndrome, and other neonatal diseases with severe neurologic and cognitive consequences. Follow-up studies of VLBW children at school age have documented increased rates of behavioral and cognitive problems, even in the absence of neurologic abnormalities identified in infancy or early childhood. A distinct pattern of behavior problems has been suggested, with high levels of activity and inattention (Buka et al 1992; Hack et al 1992; McCormick et al 1990). An increased risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disor-der (ADHD) was reported in VLBW children (Botting et al 1997; Szatmari et al 1990). The few studies that included a wider range of the LBW distribution suggest that the increased prevalence of psychiatric problems is not confined to the VLBW range but applies also to LBW children with birth weight greater than 1500 g (McCor-mick et al 1996, 1992).

We previously reported on the psychiatric sequelae of LBW (#2500 g) at 6 years of age, based on data on LBW and normal birth weight (NBW) children randomly se-lected from an urban, largely disadvantaged community, and a suburban middle class community (Breslau et al 1996a). Based on mothers’ reports elicited by structured diagnostic interviews, a higher prevalence of DSM-III-R

From the Departments of Psychiatry and Biostatistics & Research Epidemiology, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan (NB, HDC), the Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio (NB), and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor (NB).

Address reprint requests to Naomi Breslau, Ph.D., Henry Ford Health System, Department of Psychiatry, 1 Ford Place, 3A, Detroit MI 48202-3450. Received August 23, 1999; revised November 30, 1999; accepted December 3,

1999.

ADHD was observed in LBW versus NBW children, primarily in the urban setting. Data from teachers on a standardized behavior problem checklist revealed an ex-cess in attention problems in LBW versus NBW children, and the magnitude of the excess was greater in urban than suburban children. Mothers’ ratings on a parallel behavior checklist yielded consistent findings with those from teachers’ ratings.

This report focuses on the psychiatric sequelae of LBW at 11 years of age, using both mothers’ and teachers’ ratings of attention, externalizing, and internalizing prob-lems. The statistical method used in this study combines data from both informants for estimating the effects of LBW on behavior problems. The approach evaluates the extent to which the estimated effect of LBW on behavior problems varies between the two types of informants and across settings. We test whether the previously observed LBW effects on attention problems and their differential magnitude in the urban versus suburban setting are in evidence at 11 years of age, and whether LBW children have a higher incidence of clinically significant inattention during the 5-year follow-up interval. We also test the effects of LBW on externalizing and internalizing prob-lems, areas on which the evidence at 6 years of age was less clear.

Methods and Materials

Sample and Data

Random samples of 6-year-old LBW and NBW children from two socioeconomically disparate populations were identified, traced, and assessed. The 1983–1985 cohort of newborns who reached 6 years of age in 1990 –1992, the scheduled period of fieldwork, were targeted. Two major hospitals in southeast Michigan were selected, one in the city of Detroit (urban) and the other in a nearby middle-class suburb (suburban). In each hospital, for each year from 1983 through 1985, random samples of LBW and normal birth weight newborns were drawn. Children with severe neurologic impairment, chiefly cerebral palsy, severe mental retardation, or blindness, were excluded. Of the 1095 in the target sample, 823 (75%) participated in the assessment at 6 years of age. Children were assessed as they passed their sixth birthday, with those born in 1983 assessed in 1990 and those born in 1984 and 1985 assessed in 1991 and 1992, respectively. (Detailed information on the sample and the population has been published [Breslau et al 1994, 1996a].)

Five years later, in 1995–1997, the sample was reassessed, with children in each birth year cohort evaluated as they passed their eleventh birthday. Of the total sample of 823 who were assessed at 6 years of age, 32 (3.9%) moved out of state. Of the target sample of 791 remaining in the Detroit area, 717 (90.6%) were reassessed (Breslau et al 2000). At both assessments, written informed consent was obtained from the mothers.

Behavior problems in the children were evaluated by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) rated by mothers, and the Teacher Report Form (TRF) rated by teachers (Achenbach 1991a, 1991b). All assessments were conducted blindly with respect to the LBW status of the children. Assessments at age 11 were conducted blindly with respect to the results of the previous assessment. In this report, we focus on the attention problems subscale and on the internalizing and externalizing composite scales. The attention problems subscale has 20 items, among them the cardinal symptoms of ADHD (e.g., fails to finish things he/she starts; can’t concentrate, pay attention for long; can’t sit still; fidgets; daydreams or gets lost in his/her thoughts; difficulty following directions; impulsive or acts without thinking; messy work; inattentive, easily distracted; fails to carry out assigned tasks). The internalizing scale is the sum of three subscales: withdrawn, somatic complaints, and anxious/depressed. The externalizing scale is the sum of two subscales: delinquent and aggressive. T scores based on age and sex distributions of normative samples were used. Scores on these scales can also be used to identify children with clinically significant psychopathol-ogy by applying empirically based cutoffs to define cases. We used cutoffs of 60 for the internalizing and externalizing com-posite scales and a cutoff of 67 for the attention problems subscale (Achenbach 1991a, 1991b).

Statistical Analysis

A regression analytic strategy, applying generalized estimating equations (GEE; Diggle et al 1994; Liang and Zeger 1986; Zeger and Liang 1986), was used to estimate the effects of LBW on the three areas of children’s problems, namely, attention problems, internalizing, and externalizing, measured by mothers on the CBCL and by teachers on the TRF. The statistical approach allows the use of information from multiple informants (i.e., parent and teacher). Estimates of interactions between type of informant and risk factors determine whether data from multiple informants can be combined to yield a single more precise estimate of the effect of a risk factor (e.g., LBW). Also, the approach permits assessments of interactions between one risk factor and another (i.e., LBW and urban setting). The method was proposed by Fitzmaurice et al (1995) for combining data on children’s psychopathology gathered from multiple informants and was demonstrated in previous reports from this study. In this analysis, two data records are used for each child, representing mother and teacher scores on the CBCL and TRF, respectively. The basic model used to estimate the effects of LBW is displayed in the equation below. The equation does not display other terms that were included in the analysis (i.e., variables adjusted in the analysis and interactions of secondary interest).

Y5 a 1 b1(LBW)1 b2 (informant)1 b3 (setting)1 b4

(LBW 3 informant) 1 b5 (LBW 3 setting), where child’s

outcome (Y) is measured by the t score from the CBCL or TRF; LBW51 if LBW and 0 if normal birth weight; informant51 if teacher and 0 if mother; setting51 if urban and 0 if suburban. The interaction coefficient of LBW and informant, b4, tests

The coefficient for LBW,b1, in this model, which includes an

interaction between LBW and setting, estimates the effect of LBW in the suburban setting. The corresponding estimate in urban children is equal to b1 plus b5, the coefficient for the

interaction of LBW and setting (which estimates the difference between the effect of LBW in the urban and the suburban settings).

GEE provides regression coefficients and their standard errors, taking the correlation between parents’ and teachers’ ratings into account. The potential bias due to the fact that the information on each child comes from two informants is reduced and estimates are more efficient (Diggle et al 1994; Liang and Zeger 1986; Zeger and Liang 1986).

The analysis included child’s sex, maternal education, and maternal history of smoking as covariates. These were intro-duced in two successive models, with maternal history of smoking added in the second model to assess its role in the LBW– behavior problems association. Maternal smoking in pregnancy is an established risk factor for LBW (Kleinman et al 1988; Kramer 1987). In this study, the rate of smoking in pregnancy in mothers of LBW children was 39.4%, a substan-tially higher rate than the rate in mothers of NBW children, 19.3%. Further, maternal smoking has been reported to be associated with conduct problems in childhood and criminal behavior in adult males (Brennan et al 1999; Fergusson et al 1998; Ra¨sa¨nen et al 1999; Wakschlag et al 1997; Weitzman et al 1992). Information on maternal smoking was elicited from mothers at the first assessment when the children were 6 years of

age in two separate sections of the interview. The first is a series of questions on pregnancy and perinatal history, which included a question on whether or not the mother smoked daily for at least 2 months during pregnancy. The second is the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule—Revised, sub-stance use disorders section (Robins et al 1989), which provided information on smoking status up to the time of the interview. These data were used to classify mothers into three categories: smoked during pregnancy, smoked at time of initial assessment when the child was 6 years of age but not during pregnancy, and neither. (Only a handful of mothers who smoked during the index pregnancy did not smoke at the time of the initial assessment.)

Results

Description of Sample

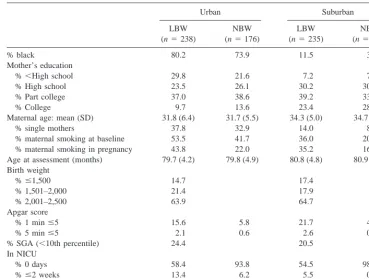

The urban and suburban subsets differed markedly in racial composition, maternal education, and maternal mar-ital status (Table 1); however, differences between the LBW and NBW subsets within settings were small. The urban subset was predominantly black and had a higher proportion of single mothers and mothers with less than high school education, compared to the suburban subset. A comparison of the initial sample of 823 with the follow-up sample of 717 revealed only minor differences.

Table 1. Sample Characteristics at First Assessment

Urban Suburban

LBW (n5238)

NBW (n5176)

LBW (n5235)

NBW (n5174)

% black 80.2 73.9 11.5 3.0

Mother’s education

%,High school 29.8 21.6 7.2 7.5

% High school 23.5 26.1 30.2 30.5

% Part college 37.0 38.6 39.2 33.9

% College 9.7 13.6 23.4 28.2

Maternal age: mean (SD) 31.8 (6.4) 31.7 (5.5) 34.3 (5.0) 34.7 (4.8)

% single mothers 37.8 32.9 14.0 8.6

% maternal smoking at baseline 53.5 41.7 36.0 20.1 % maternal smoking in pregnancy 43.8 22.0 35.2 16.7 Age at assessment (months) 79.7 (4.2) 79.8 (4.9) 80.8 (4.8) 80.9 (4.4) Birth weight

%#1,500 14.7 17.4

% 1,501–2,000 21.4 17.9

% 2,001–2,500 63.9 64.7

Apgar score

% 1 min#5 15.6 5.8 21.7 4.1

% 5 min#5 2.1 0.6 2.6 0.0

% SGA (,10th percentile) 24.4 20.5 In NICU

% 0 days 58.4 93.8 54.5 98.9

%#2 weeks 13.4 6.2 5.5 0.6

%.2 weeks 28.2 40.0 0.5

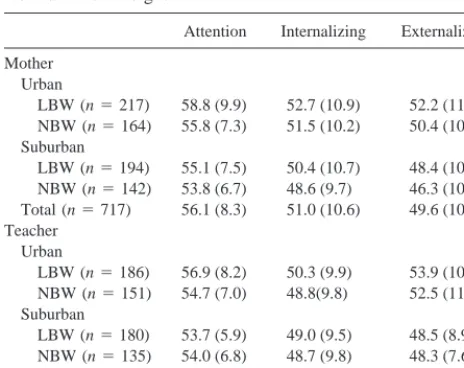

Mothers’ and Teachers’ Ratings of Behavior Problems: Descriptive Data

Table 2 presents the data on which the multivariate analysis was based. According to mothers’ ratings, LBW children scored higher (i.e., manifesting more problems) than NBW children in all three behavioral domains. According to teachers’ ratings, LBW children scored slightly higher than NBW children on attention and externalizing problems. Urban children received higher scores than suburban children on all three behavioral domains, according to both mothers and teachers.

Results from GEE Analysis of the Combined Data from Mothers and Teachers

Table 3 presents results from GEE models that estimate the effects of LBW on behavior problems as continuous measures, adjusted for setting (urban vs. suburban), child’s

sex, informant (teacher vs. mother), and maternal educa-tion (,college vs. college). Regression coefficients and standard errors are presented. These coefficients represent differences in the mean standardized ratings of behavior problems associated with each of the independent vari-ables, adjusted for all the other variables in the model. A positive value that exceeds twice its standard error indi-cates a statistically significant (,.05) excess in behavior problems associated with a given category, relative to the reference category. Interactions between informant and LBW or other risk factors were not significant, even when a liberalawas used (p,.15). The absence of a significant two-way interaction between informant and LBW and a three-way interaction of these two variables with setting indicates that the effects of LBW on behavior problems did not vary by type of informant.

A significant interaction between LBW and urban setting was observed for attention problems (p 5 .02; Table 3). Specifically, the results show a small and nonsignificant LBW effect in suburban children (estimat-ed by the coefficient of LBW, i.e., .46), whereas the LBW effect in urban children was large and statistically signif-icant (estimated by the sum of the coefficients of LBW and LBW3 urban, (i.e., .4612.14; Table 3).

No interactions were detected between LBW and setting for externalizing or internalizing problems. For external-izing problems, a significant difference was observed between LBW and NBW across settings, with LBW children scoring higher than NBW children. In contrast, for internalizing problems, the difference between birth weight groups was not significant.

No significant interactions were found between LBW and sex with respect to any of the three behavioral domains; however, there was a trend for a greater LBW effect on attention problems in males in the urban setting and on externalizing problems in males across both set-tings. In each case, the excess in problems associated with LBW was twice as large in males than in females.

We examined the potentially confounding effects of maternal smoking on the observed association between LBW and behavior problems. The results, which appear in Table 4, show that maternal smoking during pregnancy or during the child’s early years did not account for the observed effect of LBW on attention problems in the urban setting. In contrast, a comparison of the results in Table 4 to those in Table 3 shows that maternal smoking accounts in part for the effect of LBW on externalizing problems: The introduction of maternal smoking into the model reduced the coefficient of externalizing problems associated with LBW from 1.26 to .77, which was no longer statistically significant. No interactions were de-tected between maternal smoking and sex or LBW.

Apart from the observed relationship between LBW and

Table 2. Mothers’ and Teachers’ Mean (SD) Ratings at Age 11 of Three Behavior Problems by Low Birth Weight vs. Normal Birth Weight

Attention Internalizing Externalizing

Mother Urban

LBW (n5217) 58.8 (9.9) 52.7 (10.9) 52.2 (11.4) NBW (n5164) 55.8 (7.3) 51.5 (10.2) 50.4 (10.8) Suburban

LBW (n5194) 55.1 (7.5) 50.4 (10.7) 48.4 (10.1) NBW (n5142) 53.8 (6.7) 48.6 (9.7) 46.3 (10.3) Total (n5717) 56.1 (8.3) 51.0 (10.6) 49.6 (10.9) Teacher

Urban

LBW (n5186) 56.9 (8.2) 50.3 (9.9) 53.9 (10.8) NBW (n5151) 54.7 (7.0) 48.8(9.8) 52.5 (11.0) Suburban

LBW (n5180) 53.7 (5.9) 49.0 (9.5) 48.5 (8.9) NBW (n5135) 54.0 (6.8) 48.7 (9.8) 48.3 (7.6) Total (n5652) 54.9 (7.2) 49.3 (9.7) 50.9 (10.0)

Data given as mean (SD). LBW, low birth weight (#2,500 g); NBW, normal birth weight (.2,500 g).

Table 3. Regression Estimates and Standard Errors (in Parentheses) of Behavior Problems at Age 11 from Generalized Estimating Equation Analysis of Mothers’ and Teachers’ Data

Attention Externalizing Internalizing

LBW (vs. NBW) .46 (.63) 1.26a(.63) 1.14 (.59)

Teacher (vs. mother) 21.19a(.33) 1.33a(.45) 21.70a(.50)

Urban (vs. suburban) 1.21 (.68) 3.93a(.64) 1.68a(.61)

Male (vs. female) 1.49a(.47) 1.57a(.63) .53 (.59)

Mom,college (vs. college)

2.06a(.54) 3.99a(.77) .60 (.74)

LBW3urban 2.14a(.93) — —

LBW, low birth weight (#2,500 g); NBW, normal birth weight ($2,500 g).

behavior problems, several other findings are of interest. Urban children scored higher than suburban children on externalizing and internalizing problems. Child’s sex and maternal education were related to attention and external-izing problems: On both problem areas boys scored higher than girls, and children whose mothers had less than college education scored higher than children of college educated mothers. Neither sex nor maternal education was related to internalizing problems. An excess of external-izing problems was observed in children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy but not in children whose mothers smoked at the time of the initial interview but not during pregnancy. The GEE results also revealed differ-ences between informants on all three behavior problem areas: Compared to mothers, teachers gave higher ratings on externalizing problems but lower ratings on attention and internalizing problems.

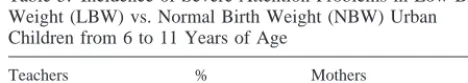

Additional Analysis: Incidence of Clinically Significant Attention Problems in Urban Children at Age 11

Applying cutoffs that define a clinically significant level of attention problems, we examined the extent to which LBW urban children showed a higher incidence of a severe level of attention problems during the 5-year

follow-up interval (Table 5 ). In each of the two analyses, one based on the CBCL and the other on the TRF, children who scored above the cutoff point at age 6 were excluded from the sample as not at risk for incidence of a clinically significant level of attention problems at age 11. Accord-ing to mothers’ ratAccord-ings, there was more than a two-fold higher incidence of severe attention problems in LBW versus NBW urban children. Similar results were observed in teachers’ data (Table 5). A parallel analysis in the suburban subset detected no differences in the incidence of clinically significant attention problems between LBW and NBW children according to either mothers or teachers (p..45).

Discussion

Information from mothers and teachers on children’s behavior problems at age 11 revealed that the effect of LBW on attention problems differed between the urban and suburban settings. Specifically, LBW signaled an excess in children’s attention problems in the urban disadvantaged community, but not in the suburban middle class community. This finding was not accounted for by history of maternal smoking during pregnancy or during the child’s early years. Furthermore, there was evidence to suggest that in the urban setting the incidence of clinically significant attention problems was more than twice as high in LBW than NBW children. With respect to externalizing problems, evidence of LBW effects was detected in both urban and suburban children, but the effect was accounted for in large part by history of maternal smoking in pregnancy. No LBW effect was observed with respect to internalizing problems.

With respect to the role of maternal smoking in child behavior problems, we found that prenatal exposure to smoking signaled an increase in externalizing problems regardless of LBW status, replicating previous reports on the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on aggression and disruptive behavior in children and crimi-nality in adult males. No association was found between maternal smoking in pregnancy and children’s attention or internalizing problems.

In this study, we examined the relationship of LBW with children’s behavior problems as dimensional vari-ables, measured by standardized ratings by mothers and teachers. Although behavior problem scales do not yield psychiatric diagnoses, the utility of dimensional measures, in terms of clinical correlates and prognosis, has been emphasized (Jensen and Watanabe 1999).

Another limitation is the reliance on mothers’ reports of smoking during pregnancy elicited when the children were 6 years of age. Of particular concern is the possibility of under-reporting; however, a bias of this type would have

Table 4. Regression Estimates and Standard Errors (in Parentheses) of Behavior Problems from Generalized Estimating Equations Analysis Controlling for Maternal Smoking

Attention Externalizing Internalizing

LBW (vs. NBW) .28 (.63) .77 (.65) 1.05 (.60) Teacher (vs. mother) 21.18 (.33)a 1.34 (.45)a 21.70 (.50)a

Urban (vs. suburban) 1.07 (.69) 3.60 (.66)a 1.53 (.63)a

Male (vs. female) 1.48 (.47)a 1.56 (.63)a .51 (.60)

Less than college (vs. college)

1.82 (.56)a 3.28 (.80)a .35 (.77)

Smoked in pregnancy .90 (.60) 2.55 (.78)a .68 (.71)

Smoked/not in pregnancyb .43 (.77) 1.43 (1.05) 1.27 (1.04)

LBW3Urban 2.16 (.93)a — —

LBW, low birth weight (#2,500 g); NBW, normal birth weight (.2,500 g).

aCoefficient exceeds twice its standard error (p,.05).

bSmoked at first assessment when child was 6 years of age but did not report

smoking during pregnancy.

Table 5. Incidence of Severe Attention Problems in Low Birth Weight (LBW) vs. Normal Birth Weight (NBW) Urban Children from 6 to 11 Years of Age

Teachers % Mothers %

LBW (n5153) 11.1a LBW (n5185) 17.3b

NBW (n5138) 5.8 NBW (n5156) 8.3

Suburban children were excluded from this analysis.

ax2(1)52.61, p5.10.

resulted in an under-estimation of the confounding effect of smoking in pregnancy on the LBW– externalizing problems association, increasing the likelihood that the “true” association is smaller than that estimated in this model.

Important strengths of our approach deserve mention. Data come from mothers and teachers, allowing a check on potential bias in mothers’ reports of behavior problems associated with LBW status (Chilcoat and Breslau 1997). The correspondence of the findings from teachers, who can be expected to be blind to the LBW status of children at 11 years of age, with those of mothers, with respect to LBW effects on attention problems, is noteworthy. In addition to the analysis of cross-sectional data at age 11, we estimated the incidence of new cases of clinically significant attention problems in LBW and NBW children. We found that, in the urban settings, LBW children had a higher incidence of clinically significant attention prob-lems than NBW children. These findings from the pro-spective data are specific to the urban setting, where we have also observed LBW effects on attention problems in the cross-sectional data at age 11 and at age 6.

Interactions between biologic vulnerabilities associated with LBW and environmental risk associated with social disadvantage have been previously reported with respect to some outcomes (Breslau 1995; Levy-Shiff et al 1994; McCormick et al 1992; McGauhey et al 1991; Werner et al 1971; Werner and Smith 1982). In previous reports from this sample we found no evidence of such an interaction with respect to the effects of LBW on IQ, neuropsycho-logic tests performance, learning disabilities, and neuro-logic soft signs (Breslau et al 1994, 1996a, 1996b, 2000; Johnson and Breslau, in press). On these other outcomes, adverse effects of LBW were observed in the urban disadvantaged community and the suburban middle class community. The possibility that LBW disadvantaged chil-dren are vulnerable to the effects of LBW on attention problems at ages 6 and 11, and to the escalation of attention problems over time calls for further research and replication in other samples.

Supported by Grants No. MH-44586 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NB) and No. DA R29 11952 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (HDC).

References

Achenbach TM (1991a): Child Behavior Checklist for Ages

4 –18. Burlington: University of Vermont, Center for

Chil-dren, Youth, and Families.

Achenbach TM (1991b): Teacher’s Report Form. Burlington: University of Vermont, Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Botting N, Powls A, Cooke RW, Marlow N (1997): Attention deficit hyperactivity disorders and other psychiatric outcomes in very low birth weight children at 12 years. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry 38:931–941.

Brennan PA, Grekin ER, Mednick SA (1999): Maternal smoking during pregnancy and adult male criminal outcomes. Arch

Gen Psychiatry 56:215–219.

Breslau N (1995): Psychiatric sequelae of low birth weight.

Epidemiol Rev 17:96 –106.

Breslau N, Brown GG, DelDotto JE, Kumar S, Ezhuthachan S, Andreski P, et al (1996a): Psychiatric sequelae of low birth weight at six years of age. J Abnorm Child Psychol 24:385– 400.

Breslau N, Chilcoat H, DelDotto J, Andreski P, Brown G (1996b): Low birth weight and neurocognitive status at six years of age. Biol Psychiatry 40:389 –397.

Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Johnson EO, Andreski P, Lucia VC (2000): Neurologic soft signs and low birthweight: Their association and neuropsychiatric implications. Biol

Psychia-try 47:71–79.

Breslau N, DelDotto JE, Brown GG, Kumar S , Ezhuthachan S, Hufnagle KG (1994): A gradient relationship between low birth weight and IQ at 6 years of age. Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med 148:377–383.

Buka SL, Lipsitt LP, Tsuang MT (1992): Emotional and behav-ioral development of low-birthweight infants. In: Friedman SL, Sigman MD, editors. The Psychological Development of

Low-Birthweight Children:Annual Advances in Applied De-velopmental Psychology. Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 187–214.

Chilcoat HD, Breslau N (1997): Does psychiatric history bias mothers’ reports? An illustration of a new analytic approach.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:971–979.

Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL (1994): Analysis of

Longitudi-nal Data. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ (1998): Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric adjustment in late adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:721–727.

Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NN, Zahner GEP, Daskalakis C (1995): Bivariate logistic regression analysis of childhood psychopa-thology ratings using multiple informants. Am J Epidemiol 142:1194 –1203.

Hack M, Breslau N, Aram D, Weissman B, Klein N, Borawski-Clark E (1992): The effect of very low birth weight and social risk on neurocognitive abilities at school age. J Dev Behav

Pediatr 13:412– 420.

Jensen PS, Watanabe HK (1999): Sherlock Holmes and child psychopathology assessment approaches: The case of the false-positive. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:138 – 146.

Johnson EO, Breslau N (in press): Increased risk of learning disabilities in low birth weight boys at age 11 years. Biol

Psychiatry.

Kleinman JC (1992): The epidemiology of low birth weight. In: Friedman SL, Sigman MD, editors. The Psychological

De-velopment of Low-Birthweight Children: Annual Advances in Applied Developmental Psychology. Norwood, NJ: Ablex,

25–35.

Kramer MS (1987): Determinants of low birth weight: Method-ological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull World Health

Organ 65:663–737.

Levy-Shiff R, Einat G, Mogilner MB, Lerman M, Krikler R (1994): Biological and environmental correlates of develop-mental outcome of prematurely born infants in early adoles-cence. J Pediatr Psychol 19:63–78.

Liang K-Y, Zeger SL (1986): Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73:13–22.

McCormick MC, Brooks-Gunn J, Workman-Daniels K, Turner J, Peckham GJ (1992): The health and development status of very low-birth-weight children at school age. JAMA 267: 2204 –2208.

McCormick MC, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM (1990): Very low birth weight children: Behavior problems and school diffi-culty in a national sample. J Pediatr 117:686 – 693. McCormick MC, Workman-Daniels K, Brooks-Gunn J (1996):

The behavioral and emotional well-being of school-age chil-dren with different birth weights. Pediatrics 97:18 –25. McGauhey PJ, Starfield BH, Alexander C, Ensminger ME

(1991): Social environment and vulnerability of low birth-weight children: A social-epidemiological perspective.

Pedi-atrics 88:943–953.

Ra¨sa¨nen P, Hakko H, Isohanni M, Hodgins S, Ja¨rvelin M-R,

Tiihonen J (1999): Maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of criminal behavior among adult male offspring in the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry 156: 857– 862.

Robins L, Helzer J, Cottler L, Golding E (1989): The NIMH

Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III, Revised. St.

Louis: Washington University.

Szatmari P, Saigal S, Rosenbaum P, Campbell D, King S (1990): Psychiatric disorders at five years among children with birthweights less than 1000g: A regional perspective. Dev

Med Child Neurol 32:954 –962.

Wakschlag LS, Lahey BB, Loeber R, Green SM, Gordon RA, Leventhal BL (1997): Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risk of conduct disorder in boys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54:670 – 676.

Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Sobol A (1992): Maternal smoking and behavior problems of children. Pediatrics 90:342–349. Werner EE, Bierman JM, French FE (1971): The Children of

Kauai. Honolulu: University of Hawai Press.

Werner EE, Smith RS (1982): Vulnerable but Invincible: A

Longitudinal Study of Resilient Children and Youth. New

York: McGraw-Hill.