Deconstructing

Socioemotional Wealth

Danny Miller

Isabelle Le Breton-Miller

There have appeared of late numerous important articles elaborating on and researching the concept of socioemotional wealth, within the last year in Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, others published in journals ranging from Administrative Science Quarterly to

Family Business Review. Given the increasing popularity and generality of the concept, it is perhaps worth revisiting it to assess its potential for enhancing our understanding of family firms. We shall examine the socioemotional wealth concept and the challenges it poses for researchers, and propose some conceptual and methodological notions for increasing its utility.

The Notion of Socioemotional Wealth (SEW)

Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Nuñez-Nickel, Jacobson, and Moyano-Fuentes (2007) have labeled the noneconomic utilities family members receive from their businesses as SEW or affective endowments. Thus, family members are said to attempt to manage their businesses not to maximize financial returns but to preserve or increase the socioemotional endowments they derive from the business (Gómez-Mejía, Cruz, Berrone, & DeCastro, 2011). The SEW perspective is founded on behavioral agency theory (Wiseman & Gomez-Mejia, 1998), which argues that preferences are shaped by existing endowments. Where major family owners or managers possess such endowments in the form of a firm they control, they may work against the interests of nonfamily owners— particularly where the endowment they are attempting to preserve is of a socioemotional nature—for example, preserving family control of the firm by avoiding profitable invest-ments and initiatives that would threaten such control.1

Please send correspondence to: Isabelle Le Breton-Miller, tel.: 1-514-340-7315; email: isabelle.lebreton@ hec.ca or [email protected] and to Danny Miller at [email protected].

1. According to Adam Smith, wealth is the annual produce of the land and labor of a society. Wealth in the form of money or talent can be stored, earns and produces something material, and is fungible. It evokes saving and reaping. Although SEW is often expressed as an endowment—it tends more toward reaping, typically in the form of the enjoyment or rent that obtains from the possession or control of a business. Here, “spending” occurs by indulging one’s preferences—e.g., having a family member serve as chief executive officer, or providing gifts to the children from the business. Thus, socioemotionalbenefitmay be as appro-priate a term as wealth or endowment.

P

T

E

&

1042-2587

Challenges in Using the Concept of SEW

Utility of the Concept

Certainly, SEW proponents are correct in saying that family firms are motivated by things other than, and perhaps in conflict with, financial objectives. But an abundance of prior research has already established that. Indeed, there is a longstanding legacy of concepts and research that has acknowledged the importance to family firms of noneco-nomic, family-centric motives, such that family members are said to exploit the business to satisfy social obligations and emotional preferences (e.g., Beckhard & Dyer, 1983; Daily & Dollinger, 1992; Kets de Vries, 1993; Taguiri & Davis, 1996; Ward, 1997). These priorities include being accommodating to relatives by giving them privileged access to the firm and its resources (Bertrand & Schoar, 2006; Kets de Vries & Miller, 1984; Kets de Vries, 1993; Morck, Wolfenzon, & Yeung, 2005; Ward, 1997).

Although there is utility in incorporating multiple differentiating priorities for family firms—or, more accurately, family members in family firms—under “one SEW umbrella,” that is true where the category helps to link causes with their effects. As we shall see, this remains a challenge, and researchers might do well to revisit the earlier socioemotional distinctions in the literature to be able to explore in greater depth and with more predictive consequences the different varieties of SEW.

Diverse Types and Sources of SEW

There are many possible types of social and affective endowment that accrue to family members as a result of controlling a business. These include the ability to enhance family reputation and social status in the community via firm contributions, to use firm financial resources to benefit one’s family or children, to provide interesting career opportunities for family members, and to satisfy family egos. Moreover, as Gómez-Mejía et al. (2011) summarize, there are a great many potential sources of these SEW priorities—patriarchal duty, altruism, pride, desire for family harmony, political power, status, and control over wealth.

Not only do SEW priorities vary among firms and even family members within a firm, they also may vary across the life cycle of a family in its firm: founders may desire a robust business to pass on to later generations, whereas later generations may wish to benefit from the wealth and community status wrought by their family firm (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2013b; Lubatkin, Schulze, Ling, & Dino, 2005). It is also likely that SEW preferences can vary significantly among family members, with, for example, family executives incorporating an economic agenda and family owners not involved in manag-ing the business given to more parochial SEW-related motivations.

Diverse SEW Outcomes

& Gomez-Mejia, 2012; Kellermanns, Eddleston, & Zellweger, 2012; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005) may create loyal partners who can actually help enhance financial perfor-mance (Berrone, Cruz, Gómez-Mejía, & Larraza-Kintana, 2010). Indeed, even the nature of the environment can determine when these SEW motives and outcomes will help or hurt a firm’s market or financial performance. For example, conservatism may be useful in more stable industries but harmful in turbulent ones (Naldi, Cennamo, Corbetta, & Gomez-Mejia, 2013).

Problems Connecting Cause and Effect

Sometimes outcomes attributed to the preservation of family SEW may be caused by factors that have little to do with those intentions. For example, limiting diversification, internationalization, risk taking, and debt may be motivated not by SEW concerns, but the quest for greater short-term financial returns (Gómez-Mejía, Makri, Hoskisson, Sirmon, & Campbell, 2010; Gómez-Mejía, Makri, & Larraza-Kintana, 2010). So can collaboration with external stakeholders (Freeman, 2010). One can only attribute these outcomes to SEW concerns where there is additional evidence as to the actual motivations behind the behavior.

One challenge in linking cause and effect relates to teasing out financial versus nonfinancial (SEW) motivations. A firm’s contributions to its community may bring both social and financial returns. Similarly, excellent financial performance may bring prestige to a family and satisfy its need for social status. Indeed, family motives may be mixed among financial and nonfinancial motivations: the desire to pass on a firm to later generations may encourage careful stewardship of the business and an effort to enhance its competitive strength. Again, the connection between motives and rewards, and among them each, becomes difficult to disentangle and will benefit from looking behind the numbers to examine motives more directly.

Not Specific to Family Firms

The generic notion of SEW preservation may not be specific to family firms. For example, entrepreneurs may favor rapid growth to preserve their social status and identity as members of the breed and because venturing provides emotional satisfaction (Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Lester, 2011). Chief executive officers of large firms may favor stable earnings to enhance their reputation among analysts as skilled managers (Healy & Wahlen, 1999). These motivations too have both emotional and social components and they are related to career and reputational endowments; moreover, some of the outcomes are similar to those favored by family owners. Again, the challenge to family business scholars will be to relate SEW priorities directly to specific family-centric concerns.

Not Exhaustive of Family Firm Priorities

of religion, the state, the market, and the community may all drive family preferences and behavior in family firms (Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, 2012). Their study may add precision and scope to discussions of family motives.

Indirect Measures

In most previous research, SEW preferences are not assessed directly. They are very rarely measured by stated family motivations but instead by examining governance variables of family involvement in ownership and management, coupled with generic outcomes such as risk aversion (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007), a lack of innovation (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011), and sustainability practices (Berrone et al., 2010), etc. It is then inferred that the sources of these practices were SEW preferences. As noted, this is a hazardous inference, as these outcomes may well be linked to conditions and pre-ferences having little to do with family SEW priorities.

In short, the very diversity of the nature of SEW priorities, the tenuous linkages between cause and effect, and the nonspecificity of some outcomes to family concerns, demand that we be precise in specifying and examining the locus, drivers and causal implications of its various components.Because of its aggregate nature, precision will be required to refine and make better use of the concept. Moreover, the temptation to always infer SEW motivations from family firm outcomes not obviously attributable short-term financial incentives does little to advance our understanding of behavior.2What is required is fine-grained information about the preferences, motivations, and social behavior of family firm owners and executives and the specific outcomes.

Modest Proposals for Moving Forward

Distinguishing Restricted Versus Extended SEW Priorities

Certainly, the notion of SEW does resonate with many of the priorities of family business owners. The challenge is to distinguish among the varieties of these priorities, to characterize them more precisely, encompass their diversity, and link them more closely to outcomes for the firm and its nonfamily stakeholders.3

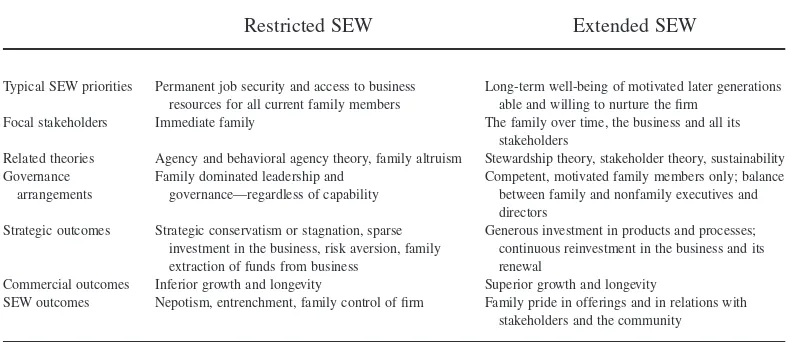

As an initial step, it may be useful to consider a basic typology that divides SEW priorities into those which are of narrow and short-term benefit to the family, and those that are of more enduring benefit to a broader range of stakeholders (see Table 1). This tentative and still crude dichotomy also helps to link different SEW priorities to divergent theoretical perspectives on family firms.

Our distinction is between what we shall call “restricted” and “extended” SEW priorities (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2013a). In essence, the former refer to priorities that

2. The situation recalls that of the early years of institutional theory. Tolbert and Zucker (1983) argued that civic governments that were late adopters of an administrative innovation did so for reasons unrelated to function and thus ascribed them to the “institutional” concern of social legitimacy. However, there was little direct evidence to support that in their study, nor was there a precise description of the nature of the institutional motivations. In the same way, some SEW studies ascribe behavior that is not positively related to financial returns to family SEW objectives without measuring if that is the case. Here too, more fine-grained analyses of the sources of behavior are called for.

are highly family centric and often run counter to the interests of nonfamily stakeholders and the firm, at least in the long run. It is such priorities that are referred to by scholars of family altruism, agency conflicts among owners and between owners and managers, and behavioral agency theory (Lubatkin et al., 2005; Morck et al., 2005; Schulze et al., 2001, 2003; Wiseman & Gomez-Mejia, 1998). These priorities may include having family members dominate management and board membership regardless of qualifications, using business resources to resolve family disputes, engaging in unrequited altruism or nepo-tism, and entrenching incompetent family leaders. Related outcomes may take the form of hyper-conservative strategies to maintain family control, inadequate innovation because family executives lack managerial ability, and restricted opportunities for career advance-ment for nonfamily managers. Although these outcomes may satisfy family socioemo-tional objectives, they can hobble firm performance and shortchange nonfamily stakeholders. Indeed, because of their ultimate harm to the business, the benefits that accrue to the family often may be short term, as rewards available from the firm will generally decrease with its decline.

There may however be positive outcomes from some very different types of family SEW priorities—which may be called extended. Although based on family prefer-ences, these encompass benefits that go beyond the family. They are referenced by scholars advocating stewardship, stakeholder, and sustainability perspectives of family firms (Allouche & Amann, 1998; Arrègle, Hitt, Sirmon, & Véry, 2007; Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Scholnick, 2008). Priorities include investing in a firm to enhance a family’s reputation with stakeholders, forming sustaining relationships with partners to increase the chances of firm survival, and investing in the community to ensure an abundance of goodwill toward the family and its business (Cennamo et al., 2012). In this case, the rewards accrue not merely to the family, but to other stakeholders as well. And the benefits to the business may be of more of a long-term nature.

It might be useful for researchers attempting to add precision to the SEW literature to begin to make the above types of distinctions in their empirical and conceptual work. Table 1

Contrasting Restricted Versus Extended SEW Priorities

Restricted SEW Extended SEW

Typical SEW priorities Permanent job security and access to business resources for all current family members

Long-term well-being of motivated later generations able and willing to nurture the firm

Focal stakeholders Immediate family The family over time, the business and all its stakeholders

Related theories Agency and behavioral agency theory, family altruism Stewardship theory, stakeholder theory, sustainability Governance

arrangements

Family dominated leadership and governance—regardless of capability

Competent, motivated family members only; balance between family and nonfamily executives and directors

Strategic outcomes Strategic conservatism or stagnation, sparse investment in the business, risk aversion, family extraction of funds from business

Generous investment in products and processes; continuous reinvestment in the business and its renewal

Commercial outcomes Inferior growth and longevity Superior growth and longevity

SEW outcomes Nepotism, entrenchment, family control of firm Family pride in offerings and in relations with stakeholders and the community

Finer-Grained Measures and Probes

More direct, multifaceted, and finer-grained measures of SEW priorities also would be useful. Moreover, it would be preferable to administer instruments incorporating such measures to different family and nonfamily owners, directors, and executives of a given company to better identify the most critical distinctions among key actors.

In short, it will be useful for scholars of SEW to be sharper in their characterizations of its nature, sources, and outcomes, and to probe more directly the motives of the family members who play active roles in family businesses.

REFERENCES

Allouche, J. & Amann, B. (1998). L’entreprise familiale, un état de la recherche. Cahiers de LAREGO, September.

Arrègle, J.-L., Hitt, M., Sirmon, D., & Véry, P. (2007). The development of organizational social capital: Attributes of family firms.Journal of Management Studies,44(1), 73–95.

Beckhard, R. & Dyer, G. (1983). Managing change in the family firm—Issues and strategies. Sloan Management Review,24(3), 59–66.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L.R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research.Family Business Review,25(3), 258–279.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gómez-Mejía, L., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures.Administrative Science Quarterly,55(1), 82–113.

Bertrand, M. & Schoar, A. (2006). The role of family in family firms. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 73–96.

Bloom, N. & Van Reenen, J. (2007). Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries.Quarterly Journal of Economics,122(4), 1351–1408.

Cennamo, C., Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L.R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth and proactive stakeholder engagement: Why family-controlled firms care more about their stakeholders.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,36(6), 1153–1173.

Daily, C.M. & Dollinger, M.J. (1992). An empirical examination of ownership structure in family and professionally managed firms.Family Business Review,5(2), 117–136.

Freeman, R.E. (2010).Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gómez-Mejía, L.R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & DeCastro, J. (2011). The bind that ties.Academy of Management Annals,5(1), 653–707.

Gómez-Mejía, L.R., Haynes, K., Nuñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly,52(1), 106–137.

Gómez-Mejía, L.R., Makri, M., Hoskisson, R., Sirmon, D., & Campbell, J. (2010). Innovation and the preservation of socioemotional wealth. Working paper. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University.

Healy, P.M. & Wahlen, J.M. (1999). A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting.Accounting Horizons,13(4), 365–383.

Kellermanns, F.W., Eddleston, K.A., & Zellweger, T.M. (2012). Extending the socioemotional wealth perspective: A look at the dark side.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,36(6), 1175–1182.

Kets de Vries, M. (1993).Human dilemmas in family business. London: Routledge.

Kets de Vries, M. & Miller, D. (1984).The neurotic organization. San Fancisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Le Breton-Miller, I. & Miller, D. (2013a). Two faces of socioemotional wealth. Working paper. HEC Montreal.

Le Breton-Miller, I. & Miller, D. (2013b). Socioemotional wealth across the family firm life cycle. Entre-preneurship Theory and Practice,37(6), 1391–1397.

Lubatkin, M., Schulze, W., Ling, Y., & Dino, R. (2005). The effects of parental altruism on the governance of family-managed firms.Journal of Organizational Behavior,26(3), 313–330.

Mehrotra, V., Morck, R.K., Shim, J., & Wiwattanakang, Y. (2011). Must love kill the family firm. Entrepre-neurship Theory and Practice,35(6), 1121–1148.

Miller, D. & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005).Managing for the long run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Lester, R. (2011). Family and lone founder ownership and its strategic implications: Social context, identity and institutional logics.Journal of Management Studies,48(1), 1–25.

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Scholnick, B. (2008). Stewardship vs. stagnation: An empirical comparison of small family and non-family businesses.Journal of Management Studies,45(1), 50–78.

Morck, R.K., Wolfenzon, D., & Yeung, B. (2005). Corporate governance, economic entrenchment, and growth.Journal of Economic Literature,43(3), 655–720.

Naldi, L., Cennamo, C., Corbetta, G., & Gomez-Mejia, L.R. (2013). Preserving socioemotional wealth in family firms: Asset or liability? The moderating role of business context. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,37, 1341–1360.

Schulze, W.S., Lubatkin, M.H., & Dino, R.N. (2003). Toward a theory of agency and altruism in family firms. Journal of Business Venturing,18(4), 473–490.

Schulze, W.S., Lubatkin, M.H., Dino, R.N., & Buchholtz, A. (2001). Agency relationships in family firms: Theory and evidence.Organization Science,12(2), 99–116.

Taguiri, R. & Davis, J. (1996). Bivalent attributes of the family firm.Family Business Review,9(2), 199–208.

Thornton, P.H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012).The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tolbert, P.S. & Zucker, L.G. (1983). Institutional sources of change in the formal structure of organizations: The diffusion of civil service reform, 1880–1935.Administrative Science Quarterly,28(1), 22–39.

Volpin, P.F. (2002). Governance with poor investor protection: Evidence from top executive turnover in Italy. Journal of Financial Economics,64(1), 61–90.

Wiseman, R. & Gomez-Mejia, L. (1998). A behavioral agency model of managerial risk taking.Academy of management Review,23(1), 133–153.

Danny Miller is Research Professor at HEC Montreal and Chair in Strategy and Family Enterprise at University of Alberta.