Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:12

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Assessing Cocurricular Impacts on the

Development of Business Student Professionalism:

Supporting Rites of Passage

William Wresch & Jessica Pondell

To cite this article: William Wresch & Jessica Pondell (2015) Assessing Cocurricular Impacts on the Development of Business Student Professionalism: Supporting Rites of Passage, Journal of Education for Business, 90:3, 113-118, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.988202

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2014.988202

Published online: 22 Dec 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 87

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Assessing Cocurricular Impacts on the Development

of Business Student Professionalism: Supporting

Rites of Passage

William Wresch and Jessica Pondell

University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, Oshkosh, Wisconsin, USA

Professionalism has a wide variety of definitions. The authors review some of those definitions and then explore stages students pass through as they move from student to business professional. Based on literature from the systems psychodynamics field, the authors examine stages in student identity building, including social defenses, sentient communities, and rites of passage. They then connect these stages to specific curricular and cocurricular efforts. A variety of cocurricular activities assisting student growth are assessed. Results indicate that activities such as attendance at business club meetings, attendance at career fairs, and participating in internships can have a positive impact on student growth and professionalism.

Keywords: assessment, business programs, cocurricular activities, extra-curricular activities, identity, professionalism, rites of passage

The assessment of student professionalism efforts is informed by two major strands of educational research. One strand focuses on definitions ofprofessionalism. While the term is widely used, it is often used in very different ways to describe very different activities and expectations. A number of studies have attempted to at least place the term in a context. A second strand of research attempts to provide effective means of developing professionalism—a growth in student maturity developed through a combina-tion of classroom and out-of-classroom activities. Studies conducted in this area generally connect specific curricular and cocurricular interventions to professional behaviors considered desirable in graduates of a professional pro-gram. We will give specific examples of these desired behaviors subsequently in this article.

While the current study will summarize much of the research concerning definitions of professionalism, this work focuses more heavily on the concept of identity crea-tion. Based on literature from the systems psychodynamics field, the current study examines stages in student profes-sional development. It then connects these stages to specific curricular and cocurricular efforts. Because efforts to

develop professionalism in students frequently takes place outside the usual classroom experience, research into the effects of cocurricular or extracurricular activities provides helpful insights into the impact of such efforts. By follow-ing hundreds of undergraduate business majors for several years, we hope to identify specific cocurricular activities that assist students as they progress through stages of iden-tity development and become business professionals pos-sessing the professional behaviors considered desirable in graduates of a professional business program.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Professionalism Defined

At one level, most people have some sense for the meaning of professionalism. A common dictionary explanation suffi-ces for most:

a: of, relating to, or characteristic of a profession, b:

engaged in one of the learned professionsc(1):

character-ized by or conforming to the technical or ethical standards of a profession(2):exhibiting a courteous, conscientious,

and generally businesslike manner in the workplace. (Mer-riam-Webster, 2014)

Correspondence should be addressed to William Wresch, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, College of Business, 800 Algoma Boulevard, Oshkosh, WI 54901, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.988202

Similar to many concepts, however, when examined more closely, a range of definitions emerges. For high school teachers trying to place their graduates, professional-ism can mean simply showing up for work on time. Responding to recent employer surveys, Bronson (2007) noted the employer call for “good interpersonal and per-sonal skills such as responsibility, self-esteem and integ-rity” (p. 30). Bronson goes on to say “It is daunting to consider exactly how to teach students to be on time, coop-erative or honest” (p. 30). These concerns are echoed by Lewis (2006), who summed up employer concerns that high school graduates were lacking in “professionalism and work ethic, which were defined as ‘demonstrating personal accountability, effective work habits, e.g., punctuality, working productively with others, time and workload man-agement” (p. 6).

Trank and Rynes (2003) provided a somewhat more demanding definition of business professionalism. Writ-ing shortly after the Enron debacle, they questioned whether business education might be headed in the wrong direction, fearing that a “variety of pressures in the organizational field of business education are rapidly steering us toward deprofessionalization” (Trank & Rynes, 2003, p. 189). They cite a variety of problems including dumbing down of courses, grade inflation, the loss of ethics classes, and the increased use of adjunct professors, among others. If business were a true profes-sion, they argue, there would be membership rules, a strong ethical component, and a foundation of generaliz-able, abstract knowledge useful as professionals respond to a variety of situations, including changes in the underlying knowledge base.

Where do these views and histories of professionalism leave us? They remind us that the term can be used so loosely it can refer to high school graduates deciding to show up for work on time, while also connecting to tradi-tional professions setting standards for behavior that serve the public interest—high standards of practice that preserve life and liberty. While we recognize the wide range of defi-nitions and applications of the term professionalism, at some point we need to pick one definition and institutional-ize it in the curriculum. Our preference has been the Trank and Rynes (2007) definition of business professionalism with its three main components: membership rules, a strong ethical component, and a foundation of generalizable, abstract knowledge. Two of those components we can point to in any good business curriculum. Ethical instruction is infused into multiple courses, and typical business curricula provide solid foundations in the business principles students will apply over their careers.

The more complicated component is membership. On the surface this could be something as simple as taking a test and paying dues, but we know from anthropologic research that there is more to the process of being a mem-ber. To get a better understanding of the membership

process, we also turn to the work of Petriglieri and Petri-glieri (2010).

The Process of Becoming Professional

A substantial body of literature reviews student develop-ment during college (Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005), but a somewhat different view emerges as I consider the transi-tion from the university into professional careers. An inter-esting description of this process is presented by Petriglieri and Petriglieri (2010). Describing business schools as iden-tity workspaces, they describe the role of business schools in helping students build an identity. They note that as cor-porate environments transform and provide fewer opportu-nities for employees to build identities, it falls on business schools to provide these experiences through identity work-spaces. They build on systems psychodynamics literature to explain necessary elements of identity building, including social defenses, sentient communities, and rites of passage.

Social defenses are “collective arrangements—such as an organizational structure, a work method, or a prevalent discourse—created or used by an organization’s members as protection against disturbing affect derived from external threats, internal conflicts, or the nature of their work” (Pet-riglieri & Pet(Pet-riglieri, 2010, p. 48). One presumes that the typical business school provides just such a safe organiza-tional structure because it resembles experiences students have had since childhood, experiences that have largely been successful with only occasional periods of anxiety.

A second element to an identity workspace is a sentient community, defined as “groups with which human beings identify themselves” (Petriglieri & Petriglieri, 2010, p. 48). Among important “sentient groups are the profes-sional communities that individuals invest in, relate to, and identify with” (Petriglieri & Petriglieri, 2010, p. 48). They pointed out that this identification process can begin even before an individual is a member of the community. They use the example of medical students who identify with the community of doctors even though they have yet to reach that level, and we could easily posit such a rela-tionship developing for future accountants as they begin their accounting coursework, already identifying with their future profession.

The third element in identity building is the rite of pas-sage. Such rites are said to consist of three stages—separa-tion, disorientastages—separa-tion, and incorporation. Anthropologists argue these three stages are universal across cultures and across centuries. As educators, we see this rite of passage in our first-year students as they make the transition from high school to college—separation from old friends and home, disorienting first weeks of college, and final adjustment to college status. We see them repeat this process as students move through internships and finally to graduation.

If we accept this model of identity development, and if we accept our role in helping the process, our next question

114 W. WRESCH AND J. PONDELL

becomes, how do we optimize our role helping our students become business professionals? How does a college of business become an identity workspace? We essentially have two approaches—actions we can take within our clas-ses—curricular efforts, and actions we can take beyond our classes—cocurricular efforts. The efforts being reported in this study relied mainly on cocurricular efforts, so some background on such efforts follows.

Cocurricular Activities and General Student Outcomes

It is commonly assumed that engagement in cocurricular activities improves a variety of student and curricular out-comes. Writing in the context of sustainability education, one author predicts that “cocurricular options for sustain-ability can allow students the opportunity for additional experiential and applied learning outside the classroom” (Rusinko, 2010, p. 508). She includes such cocurricular examples as green or eco-fashion oriented speakers for fashion merchandising majors, a student-run business to recycle clothing, working with campus dining services to purchase locally grown foods, and campus service days to clean up local parks and recreation areas. While these appear to be interesting and worthwhile activities, she is unable to produce any evidence that such activities result in additional student learning.

A study conducted at Hong Kong Baptist University (Leung, Ng, & Chan, 2011) involved students in three cocurricular activities: a business talk series, and two busi-ness simulation competitions. Results were very disappoint-ing. Not only did over 40% of participants not complete their involvement in these activities, but those who did had worse course grades than those who did not. Study authors concluded that students felt the cocurricular activities sim-ply used up time that could have been better applied in studying for class.

A study conducted at Georgia Tech (Gordon, Ludlum, & Hoey, 2007) attempted to correlate results of the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) with such outcomes as freshman retention, grade point average, pursuit of grad-uate education after graduation, and employment upon

graduation. Among engagement measures are such features as active and collaborative learning, and enriching educa-tional experiences. The study authors concluded that “taken overall, the NSSE benchmarks provide very little predictive power on the student outcomes of concern” (Gordon et al., 2007, p. 28).

The failure to produce evidence that cocurricular activi-ties have a significant impact on student outcomes may be evidence that cocurricular activities are ineffective—a waste of effort—or, the lack of such evidence may be the result of poor research methods. For example, a grade point average or a job after graduation can be the result of many factors.

METHOD

In another attempt to determine whether cocurricular activi-ties could help students develop professionalism, a multi-year study was conducted at a large (over 2,000 undergrad-uate business majors) Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business–accredited business program in the United States. One of the six learning goals for the program is student professionalism: students will conduct them-selves in a professional manner. Students will be able to transition from student to business professional.

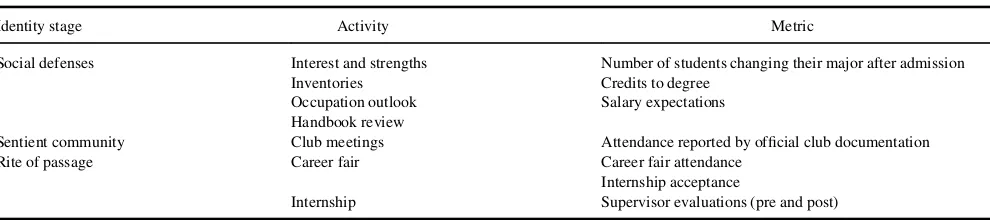

To meet these defined goals, the college created a set of requirements for admission to the college and then for grad-uation from the program. These requirements went into effect for students being admitted to the college in fall 2011. These activities are broken down into the three stages of identity building (see Table 1). Student data was collected from 2007—before the new admission requirements— through 2014. A variety of metrics was used to determine student outcomes.

Social Defenses

These are collective arrangements meant to protect mem-bers against experiences that could cause anxiety. Cer-tainly one source of anxiety is selecting the ideal college

TABLE 1 Evaluation Metrics

Identity stage Activity Metric

Social defenses Interest and strengths Inventories Occupation outlook Handbook review

Number of students changing their major after admission Credits to degree

Salary expectations

Sentient community Club meetings Attendance reported by official club documentation Rite of passage Career fair Career fair attendance

Internship acceptance

Internship Supervisor evaluations (pre and post)

major. Activities to help with this decision included a per-sonal inventory and a review of career data in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, 2014)Occupational Out-look Handbook.

Interest and strengths inventories. Students were required to complete the interest profiler through WisCa-reers (2014) before admission to the college. This profiler is based on Dr. John Holland’s theories and career classifi-cations. His theory is based on the assumption that occupa-tions are an extension of people’s personalities (WisCareers, 2014). As part of their admission application, students were required to explain why the business major they chose (why marketing and not human resources?) was a good match for their personalities. In addition, in their professional skills in business class, all students completed StrengthsQuest (2014). This assessment pulls out their top five strengths and helps students connect those strengths with careers and helps them articulate how those strengths fit the needs of certain industries and professions (Hodges & Harter, 2005).

At the time of their admission to the college, students were asked to describe what the BLSOccupational Outlook Handbooksays about job availability and expected starting salaries.

Results. The first assumption was that by creating more intentional activities prior to major selection, students would change their majors less and have fewer credits to degree. This was achieved. Average credits to degree dropped by 1.3, and average major changes after admission to the college dropped by 0.045. For this college, that resulted in a savings of 559 credits in the first year of imple-mentation. So it appears students now entered their final two years more directed in their course selection and in their major selection (see Table 2).

Second, we assumed that by researching careers, stu-dents would have a more realistic expectation of their career choice. The measure we used to determine success of this goal was salary expectations. In 2011, student sur-veys revealed significant numbers of students with inaccu-rate expectations about potential salaries in their chosen fields. The table below indicates student understanding of salaries as first year students and at admission to the college

(third-year students). As can be seen, after implementation in 2011, students in 2012 scaled back their salary expecta-tions to more realistically reflect actual college of business starting salaries (see Table 3).

Sentient Communities

In this stage of development, students begin to identify with their professional community. Measurement here was con-ducted by reviewing business club attendance. The college supports 12 business clubs in all areas of business. Meet-ings are usually held at 5 p.m., with most clubs meeting biweekly. It is the norm to invite company representatives to campus to make presentations at these meetings. Begin-ning in fall 2011, students were required to attend at least three business club meetings before admission to the col-lege. The intent of this requirement was for students to be aware of the culture of business and to begin to spend time with their professional peers.

Results. The measure used to assess the success of the goal of increased club engagement was overall attendance. As would be expected, club attendance by students increased dramatically. The accounting club provides a good example. Averaging about 48 students per meeting just before the new requirements were to take effect, atten-dance averaged over 72 one year after the new requirements took effect. The result was significantly increased engage-ment between students and employers—the enhanceengage-ment of professional communities (see Table 4).

In addition, another result of this implementation was earlier leadership development of the students. Based on qualitative data from both the marketing club and Society for Human Resource Management (human resources club), they saw students taking on executive board positions earlier in their career and being able to progress through leadership

TABLE 2

Credits to Degree and Major Changes

Time Total credits to completion Major changes n

Before Fall 2011 133.461 1.345 784 After Fall 2011 132.133 1.3 430

p <.05 <.05

TABLE 3 Salary Expectations

Median Percentage expecting over $60,000 at graduation

Year of study 2011 2012 2013 2011 2012 2013

First-year students $45,000–$50,000 $50,000–$55,000 $50,000–$55,000 16.00% 20.00% 27.30% Third-year students $45,000–$50,000 $45,000–$50,000 $40,000–$45,000 16.00% 7.88% 4.86% Average actual salary $41,037 $41,862 $41,704

116 W. WRESCH AND J. PONDELL

positions earlier because they had engaged with the club their freshman year instead of the traditional junior year.

Rites of Passage

Rites of Passages are shared experiences that all mem-bers progress through. According to Petriglieri and Pet-riglieri (2010), rites of passage are said to consist of three stages—separation, a period of disorientation, and incorporation. Two activities—career fair attendance and the internship—were seen as contributing to this rite of passage.

Career fair attendance. Once each semester, 130– 150 businesses put on a career fair for the university in this study. Businesses are generally looking to hire either interns or permanent employees, although a few also recruit part-time employees. With the new attendance requirement in 2011, it was hoped more students would not only attend the fair, but that internship or job attainment through this venue would increase. Results showed both of these to be the case. Prior to the new requirement, in spring 2011, only 18% of students obtained their internships through interac-tions at the career fair. After the implementation of the new admissions requirements, by spring 2013, 22% of students obtained their internships through interactions at the career fair and attendance had increased 19%. By spring of 2014, internship attainment through the career fair increased to 25% and attendance remained steady (see Table 5).

Another measure used to assess the impact was if stu-dents would find internships earlier in their college career. The data show the significant impact on when students began their internships. In fall 2011, the average student had earned 109.7 credits prior to starting his or her intern-ship. The semester following the first required career fair, that number dropped by a statistically significant amount (p<.05) to 103.4 credits (see Table 6).

By obtaining internships earlier, students are able to stay at an internship longer and learn more, or students have the ability to do a subsequent internship.

Internships. All College of Business students at the university being studied are required to complete an intern-ship to graduate. Internintern-ships may be as short as 100 hours, but most are at least ten weeks in duration and many are longer. Internships may be done any time after admission to the college. Students are paid for their internship and apply directly to companies. All internships are approved by the Professional Development Director to ensure that the internship is educational.

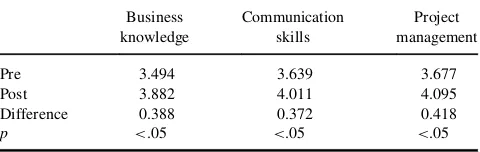

Results. Supervisors were asked to complete a pre-and postassessment of their interns related to the learn-ing goals of this College of Business. Students were rated on their business knowledge, communication skills, and project management skills. The data below shows significant improvement consistently in those three learning goals each semester. The data are from spring 2012. Ratings are from 1–5, with 5 being the highest (see Table 7).

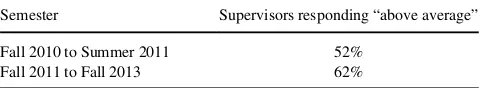

While the data in Table 7 show individual interns mak-ing significant learnmak-ing improvement each semester, a mea-sure was also found to show improvement in the college’s overall intern performances since implementation. To do this, the supervisor end of semester evaluation was used. A question asked consistently each semester to supervisor is, In general, how do interns from this university compare to interns from other business schools? The results are shown in Table 8.

This is a statistically significant improvement, with ap

value of<.05. Since the implementation of the new

profes-sionalism initiatives, it would appear students are succeed-ing in this crucial rite of passage.

TABLE 4

Average Club Meeting Attendance

Accounting club Average meeting attendance

Fall 2010 48.5

Fall 2012 72.5

TABLE 5

Career Fair Attendance Impact

Time Attendance Internship obtained through career fair Spring 2011 795 18%

Spring 2013 947 22% Spring 2014 941 25%

TABLE 6

Credits at Time of Internship Attainment

Time M SD Population

Fall 2011 109.7 23.3 99 Spring 2012 103.4 24.4 113

TABLE 7

Supervisor Assessment of Student Business Knowledge

Business

Pre 3.494 3.639 3.677 Post 3.882 4.011 4.095 Difference 0.388 0.372 0.418

p <.05 <.05 <.05

DISCUSSION

While a wide range of definitions for professionalism can be found in the literature, we have based the work on the Trank and Rynes (2003) definition ofbusiness professional-ism with its three main components: membership rules, a strong ethical component, and a foundation of generaliz-able, abstract knowledge. The process of membership was of interest to us, and was informed by the work of Petri-glieri and PetriPetri-glieri (2010). They built on systems psycho-dynamics literature to explain necessary elements of identity building, including social defenses, sentient com-munities, and rites of passage.

The first efforts instituted to help students build their identity in the social defenses stage were the surveys and required readings. Pinning metrics such as credits to degree and changes in major directly to these activities is difficult, but measureable changes in behavior did occur.

The second efforts at creating an identity workspace involved creating a sentient community. The business clubs became a chance for students to spend social time with other business students. Also, because a common club prac-tice is to bring in guest speakers from industry, these meet-ings were a chance to meet and hear from young professionals. Attendance figures indicate increased involvement in such clubs. Membership in a business club is not identical to membership in the business community, but we accept it as a useful initial step.

The most significant of the cocurricular efforts studied focused on the final stage—the rite of passage. One of those efforts included at least one visit to the campus career fair to meet with company representatives. The increase in the number of students who found an internship through the career fair (25%) and earlier obtainment provides two pieces of evidence of the value of the fairs in linking stu-dents to the professional community.

The internship requirement provides the classic rite of passage. Students are separated from their usual friends and classmates while on the job, they have the expected period of unease as they attempt to fill the role of business profes-sional, and then they have the status change upon successful completion of the internship. Because an internship is required for graduation in this program, all students partici-pate in this rite of passage. Here measurement seems more direct and more conclusive. Employers determined for themselves if students performed in a satisfactory man-ner—in a manner appropriate to the business environment.

Their reviews reveal that the experience was a positive one for the vast majority of students with 96% of students receiving favorable ratings by their immediate supervisor and the overall evaluation of this college’s interns com-pared to other business schools continuing to rise.

In conclusion, it would appear the cocurricular elements measured in this study show students were assisted in mov-ing successfully toward becommov-ing members of the business profession. The systems psychodynamics literature inter-preted by Petriglieri and Petriglieri (2010) provided a useful frame in recognizing stages in identity building. Cocurricu-lar activities did help support the stages of identity develop-ment leading to the professional membership described by Trank and Rynes (2003). It is hoped that the theoretical ori-entation of the study and the suggested interventions are of value to others seeking to help students become accultur-ated into their new profession.

REFERENCES

Anderson, M., & Escher, P. (2010). The MBA oath. New York, NY: Penguin.

Bronson, E. (2007). Helping CTE students learn to their potential. Techni-ques: Continuing Education & Careers,82, 30–31.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2014).Occupational outlook handbook, Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/ooh/

Gordon, J., Ludlum, J., & Hoey, J. J. (2008). Validating NSSE against stu-dent outcomes: Are they related?Research in Higher Education,49, 19–39.

Hodges, T., & Harter, J. (2005). A review of the theory and research under-lying the StrengthsQuest program for students. The quest for strengths.

Educational Horizons,83, 190–194.

Leung, C. H., Ng, C. W., & Chan, P. O. (2011). Can cocurricular activities enhance the learning effectiveness of students?: An application to the sub-degree students in Hong Kong.International Journal of Teaching

and Learning in Higher Education,23, 329–341.

Lewis, A. C. (2006). Necessary basic skills.Tech Directions,66(4), 6–8. Merriam-Webster. (2014).Professionalism. Retrieved from http://www.

merriam-webster.com/dictionary/professionalism

Mosher, F. (1982).Democracy and the public service(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005).How college affects

stu-dents: Volume 2, a third decade of research. San Francisco, CA:

Wiley.

Petriglieri, G., & Petriglieri, J. L. (2010). Identity workspaces: The case of business schools.Academy of Management Learning & Education,9, 44–60.

Rothman, M., & Lampe, M. (2010). Business school internships: Sources and resources.Psychological Reports,106, 548–554.

Rusinko, C. A. (2010). Integrating sustainability in management and busi-ness education: A matrix approach.Academy of Management Learning

and Education,9, 507–519.

StrengthsQuest. (2014).About. Retrieved from http://www.strengthsquest. com/content/141728/index.aspx

Trank, C. Q., & Rynes, S. I. (2003). Who moved our cheese? Reclaiming professionalism in business education.Academy of Management

Learn-ing and Education,2, 189–205.

WisCareers. (2014).John Holland’s theory. Retrieved from http:// wiscareers.wisc.edu/C_Occupations/CareerInterests/HollandsTheory. asp?_from=o

TABLE 8

Supervisors Rating Interns “Above Average”

Semester Supervisors responding “above average”

Fall 2010 to Summer 2011 52% Fall 2011 to Fall 2013 62%

118 W. WRESCH AND J. PONDELL