ABSTRACT

This paper makes use of data collected in a randomised controlled trial that was designed to test the efficacy of postpartum breastfeeding counselling to increase exclusive breastfeeding among term low birth weight infants in Manila during the first six months. Mothers were randomised to a control group or one of two home visit interventions: by trained breastfeeding counsellors or child care counsellors without breastfeeding support training. Sixty mothers received peer breastfeeding counselling while a further 119 mothers did not. The median duration of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers who received counselling was five weeks versus two weeks among those who received no counselling (p<0.001). Exclusive breastfeeding was interrupted to offer infants water, traditional herbal extracts or artificial baby milk. Mothers who interrupted exclusive breastfeeding claimed they had insufficient milk or that their infants had slow weight gain. Early and sustained breastfeeding support will enable mothers to exclusively breastfeed low birth weight infants for the first six months.

Keywords: exclusive breastfeeding, low birth weight Breastfeeding Review 2009; 17 (3): 5–10

When and why Filipino mothers of term low birth weight

infants interrupted breastfeeding exclusively

Grace V Agrasada MD, MSc, PhD

Elisabeth Kylberg PhD

INTRODUCTION

Infants born at term with a birth weight of less than 500 grams are considered to have a low birth weight (LBW) (World Health Organization 199). Adair and Popkin (1996) have found that Filipino infants born at term and with weight less than 500 grams were less likely to be breastfed than their heavier birth weight counterparts and when breastfed, they were breastfed less frequently and for a shorter duration compared with infants born heavier. Pérez-Escamilla and co-workers (1995) reported that higher birth weight was positively associated with exclusive breastfeeding. Exclusive breastfeeding may save lives (Jones et al 003) and even though LBW infants were three times more likely to die in infancy than infants with higher birth weights (Hong & Ruiz-Beltran 008), only 1.4% of LBW infants in the Philippines were reported to be exclusively breastfed at six months (National Statistics Office 2003).

Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for all infants, including LBW infants (World Health Organization 003). Breastmilk only for the first six months reduces diarrhea and respiratory morbidity and mortality (Arifeen et al 001). Breastfeeding is associated with a positive neurodevelopment outcome essential to LBW infants (Rao et al 00). Furthermore, mothers who breastfeed exclusively benefit from lactation amenorrhea (World Health Organization Task Force on Methods for the Natural Regulation of Fertility 1999) which indirectly influences infant mortality through birth spacing and improved maternal health. Complementary feeding before the age of six months has not shown any growth advantage (Dewey et al 1999; Kramer et al 003). Non-breastmilk feeds before the age of six months makes the infant susceptible to infection caused by contamination of the food in combination with poor nutrition. The known relationship

between supplementation before six months and cessation of breastfeeding emphasises the importance of strategies to maintain exclusive breastfeeding during this period (Hörnell, Hofvander & Kylberg 001a).

We have previously reported results of a randomised controlled trial (Agrasada et al 2005) designed to test the efficacy of peer counselling among mothers of term LBW infants. It was found in that trial that mothers who received breastfeeding counselling were 6.3 times more likely to continue to breastfeed exclusively and 3.7 times more likely to continue any breastfeeding during the first six months compared with mothers who did not receive such counselling. The aim of this article is to describe when and why mothers of term LBW infants first introduced non-breastmilk liquid and solids to their infants and whether counselling had any effect upon the timing or reasons for weaning.

METHODS

eight or higher at five minutes. The infants were term or born 37–4 weeks of gestation (Edmonds 007), as computed from the mother’s last menstrual date and confirmed by Ballard scoring performed by a trained pediatrician (Ballard, Novak & Driver 1979). The following were excluded: mothers on medications that compromise breastfeeding; infants with cranio-facial abnormalities incompatible with breastfeeding; and mother-infant pairs who would not stay together during the study period.

Demographic information and breastfeeding knowledge and intentions were collected at recruitment by interview prior to randomisation. Infant feeding data were collected by only one interviewer at the hospital during seven infant visits which started at two weeks then occurred monthly until six months. These visits were within two weeks of each counselling session, for those mothers who received counselling. During hospital visits, a trained interviewer asked them to carefully recall when and how the infant had been fed, beginning with the past 4 hours, then each prior week until the previous interview (World Health Organization 1991). If any non-breastmilk liquid or solids were given, the mother was asked the primary reason for such action. Breastfeeding was reported as exclusive if the infant received only mother’s milk (Labbok & Krasovec 1990). Exclusive breastfeeding was regarded as being interrupted at the first instance when the infant had received any non-breastmilk liquid or solids.

The sample size for the randomised controlled trial had an 80% power to identify a 30% absolute difference in exclusive breastfeeding between intervention groups at six months. After adjusting for a 0% attrition rate, 04 mother-infant pairs were recruited for the original study. A total of 179 (88%) mother-infant pairs completed the trial. It was found that 4 mothers exclusively breastfed their infants during the first six months: two of these mothers received no breastfeeding counselling, whilst others did.

This paper focuses on when, how and why 38 mothers with counselling, and 119 mothers without counselling, first interrupted exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months.

Statistical analysis

For data analyses the STATA 7.0 statistical software were used as previously (Agrasada et al 005). Chi-squaredanalyses were used to test differences in proportion and percentages. The median duration of exclusive breastfeeding was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier survival table.

RESULTS

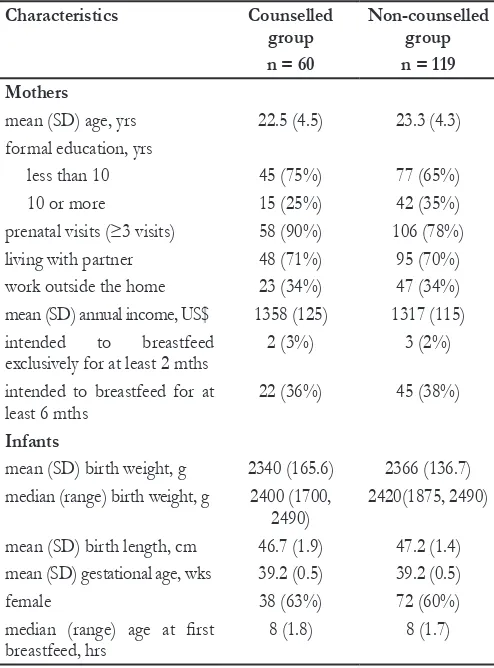

Table 1 shows selected characteristics of the 179 participants who completed the trial. At recruitment, one third of the mothers in each group intended to breastfeed their infants for at least six months. None of the mothers had previously received information on how long an infant is recommended to receive breastmilk; neither did they have knowledge of why an LBW infant, particularly, would benefit from breastmilk. None of the infants of the counselled mothers used a pacifier, whereas 10% of the infants of mothers without counselling did.

Figure 1 shows when exclusive breastfeeding was first interrupted. The median duration of exclusive breastfeeding by mothers who received breastfeeding counselling and by those who did not, was five weeks and two weeks, respectively (p<0.001). When introduced initially, non-breastmilk liquids were given in small amounts (1– ounces) as were solids (half to one teaspoon). All non-breastmilk liquids were given in feeding bottles; all solids were given with a spoon. Solid foods given to infants were mainly prepared at home. Non-breastmilk items were introduced to

- - - mothers who received counselling

___ mothers with no counselling

Figure 1: Proportions of mothers who breastfed exclusively

during the first six months.

prenatal visits (≥3 visits) 58 (90%) 106 (78%)

living with partner 48 (71%) 95 (70%)

work outside the home 3 (34%) 47 (34%)

mean (SD) annual income, US$ 1358 (15) 1317 (115) intended to breastfeed

exclusively for at least mths

(3%) 3 (%)

intended to breastfeed for at least 6 mths

(36%) 45 (38%)

Infants

mean (SD) birth weight, g 340 (165.6) 366 (136.7) median (range) birth weight, g 400 (1700,

490)

40(1875, 490)

mean (SD) birth length, cm 46.7 (1.9) 47. (1.4)

mean (SD) gestational age, wks 39. (0.5) 39. (0.5)

female 38 (63%) 7 (60%)

median (range) age at first breastfeed, hrs

8 (1.8) 8 (1.7)

infants either by mothers themselves (75%) or by grandmothers (5%). Twenty-two counselled and two non-counselled mothers did not interrupt exclusive breastfeeding during the six month period; hence, only the 38 counselled and 117 non-counselled mothers will be discussed hereon.

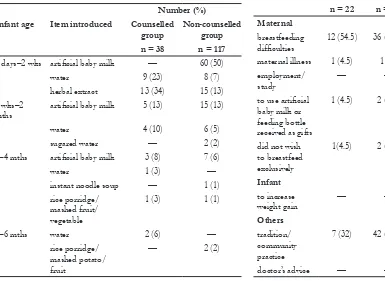

The first two weeks after hospital discharge

Table2 shows the first instance when the infants received non-breastmilk liquid or solids and what items were introduced. As soon as mothers arrived home from the hospital, some of them introduced non-breastmilk items. While both groups of mothers interrupted exclusive breastfeeding, the groups differed as to what was first given to their infants. For example, the majority of non-counselled mothers introduced artificial baby milk first in comparison to counselled mothers who introduced water first. Similar proportions of mothers from each group introduced traditional herbal extracts. Mothers who introduced artificial baby milk stated that their infants needed more than breastmilk or that ‘breastmilk is insufficient feeding for small babies’. Those who gave water to infants stated that water was needed at the end of a breastfeeding session — just as a meal is ended with a drink. Water was also given to ‘ease the digestion’, ‘keep the mouth clean’, and/or ‘refresh infants in a warm climate’. Bottled water, occasionally boiled, was given in amounts varying from a few drops via medicine droppers up to a few ounces using feeding bottles. Traditional herbal extracts such as oregano and ampalaya

were given once or twice to infants upon arrival home from the hospital. These extracts were believed to cleanse the intestines and lessen yellowish skin discoloration. Three mothers decided

to give artificial baby milk to show appreciation for the feeding bottles or tins of artificial baby milk given by friends. One non-counselled mother had viral influenza and stopped breastfeeding exclusively following a doctor’s advice.

Between two weeks and two months

Table 3 shows the reasons mothers gave for interrupting the exclusivity of breastfeeding. A total of 3 mothers, 9 (4%) of those who were given counselling and 3 (0%) of those without counselling, interrupted exclusive breastfeeding during this period. A major reason cited for the interruption was maternal dissatisfaction with infant size or appearance since mothers compared their own infants with artificially-fed infants. Those mothers who started artificial-feeding to increase infant weight said ‘my infant looks very thin’ or ‘grows very slowly’ or ‘formula is what most infants get in my neighborhood’. Another common reason to interrupt exclusive breastfeeding at this stage was a mother’s return to employment. Mothers knew that their workplace establishments do not support breastfeeding. A further reason was maternal illness. Two mothers got ill; one had viral influenza and followed her physician’s advice to artificially feed. The other mother decided it was time to give artificial baby milk.

Table 2. Infant age when exclusively breastfeeding was first

interrupted

Number (%)

Infant age Item introduced Counselled

group

Non-counselled group

n = 38 n = 117

3 days– wks artificial baby milk — 60 (50)

water 9 (3) 8 (7)

herbal extract 13 (34) 15 (13)

wks– mths

artificial baby milk 5 (13) 15 (13)

water 4 (10) 6 (5)

sugared water — ()

–4 mths artificial baby milk 3 (8) 7 (6)

water 1 (3) —

instant noodle soup — 1 (1)

rice porridge/

Between two and four months

During this period, 5 (14%) counselled mothers and 9 (8%) non-counselled mothers introduced non-breastmilk items. The following reasons were given: ‘to fatten up my baby’, ‘my baby is well anyway, and is ready for table foods’, ‘to prevent me from getting so exhausted as when I am breastfeeding exclusively’, ‘so I don’t get very hungry just breastfeeding exclusively’, and ‘I like a relative to help me feed my son’.

Between four and six months

Two mothers, who had received breastfeeding counselling, decided to reduce the number of breastfeeds by giving water in addition to breastmilk. One mother said she was exhausted from breastfeeding; the other said she was getting very thin. One non-counselled mother fed her infant rice porridge because other mothers in her neighborhood were doing that. Another non-counselled mother gave mango to her infant because her infant was grabbing food.

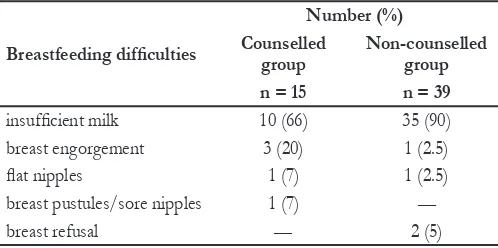

Breastfeeding difficulties during the first 14 days

Unsolved problems encountered during breastfeeding were the most frequent reasons why mothers introduced non-breastmilk feeds (Table 3). Breastfeeding difficulties were reported by 15 counselled mothers and 39 non-counselled mothers (Table 4) and the problems reported by both groups of mothers were similar. Counselled mothers, however, claimed they learned how to manage the problems through the breastfeeding counselling they received; whereas non-counselled mothers were unable to cope. For example, one counselled mother had varicella and had some pustules in her breast but none in the areola; she expressed milk manually, fed her infant by cup and resumed feeding at the breast after a week. Counselled mothers continued breastfeeding despite breastfeeding difficulties, compared to non-counselled mothers (difference = 54%; 95% CI 48–60%, p> 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Mothers without counselling interrupted exclusive breastfeeding sooner than those mothers who had received counselling. In some instances, water, traditional herbal extracts and artificial baby milk were given to infants as soon as discharged. Most mothers who received counselling gave their infants small amounts of water and continued to breastfeed. Comparably, most non-counselled

mothers gave artificial baby milk and terminated breastfeeding. This highlights the importance of the first two weeks as a period when breastfeeding support is necessary to improve the duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Water supplementation has been shown to increase the infant’s risk of gastrointestinal infection (Popkin et al 1990) and reduces breastmilk intake (Aghaji 00). Supplementation with artificial baby milk has also been associated with shorter breastfeeding duration (Hörnell, Hofvander & Kylberg 001b). Unresolved breastfeeding issues, primarily perceived insufficiency of milk, and prevailing community infant care practices were the most common reasons why mothers interrupted exclusive breastfeeding early. From two weeks onwards, mothers introduced artificial baby milk, aware that workplaces in the Philippines hardly support breastfeeding. Mothers who are unhappy about the weight gain of their infants must understand that catch up growth is possible with exclusive breastfeeding (Lucas et al 1997). The reasons why mothers introduced non-breastmilk liquids and solids were similar to those given by mothers terminating breastfeeding in a study in Brazil (Martines, Ashworth & Kirkwood 1989). The reasons given by non-counselled mothers for introducing non-breastmilk feeds reflect lack of breastfeeding knowledge and support. Most of the reasons for interrupting exclusive breastfeeding were modifiable and hence interventions should be possible.

The practice of giving water to infants was observed in this study, as it was in other studies in regions with warm climates (Eregie 001). The reduction of exclusive breastfeeding among Filipino infants by early use of non-nutritive liquids was consistent with observations by Valdecanas (1981) and Zohoori, Popkin and Fernandez (1993). The same effect on exclusive breastfeeding was reported by Maninang-Dalisay, Valdecanas and Lipton (1986) after Filipino LBW infants received solids before the age of 4 months. As in other studies, mothers in this present study continued to breastfeed exclusively, despite an interruption if they were able to get support in managing their breastfeeding problems (Fahy & Holshier 1988). Longer breastfeeding was associated with higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding (Arlotti et al 1997). Breastfeeding, in turn, will promote faster growth in infants compromised by poor growth

in utero (Fewtrell et al 001).

Similar to the findings of Binns and Scott (2002), perception of milk insufficiency was the leading breastfeeding issue reported by mothers. Mothers of LBW infants have distinct feeding challenges (such as a frail infant or a weak suck of the infant) and expectations (such as rapid catch-up growth) that breastfeeding counselling has to specifically address. Breastfeeding support provided to mothers must explore maternal expectations of breastfeeding, particularly among mothers of LBW infants. Mothers who received counselling experienced as many breastfeeding problems as those without support, possibly because they were more aware of their breastfeeding situation. In contrast, those without counselling may be less confident of their own breastfeeding experience or

Breastfeeding difficulties

insufficient milk 10 (66) 35 (90)

breast engorgement 3 (0) 1 (.5)

flat nipples 1 (7) 1 (.5)

breast pustules/sore nipples 1 (7) —

breast refusal — (5)

Table 4. Breastfeeding difficulties reported by mothers who

may have dismissed the problem by terminating breastfeeding. Breastfeeding support resulted in these mothers breastfeeding exclusively for a longer period of time than they had initially planned to do, as compared with non-counselled mothers. By delaying the introduction of non-breastmilk feeds, the exclusivity of breastfeeding was sustained and the possibility of continued breastfeeding enhanced.

The strength of this study lies in its collection of longitudinal data. Our data showed how mothers fed their infants and explored the decisions that immediately preceded them. As the data were collected monthly, it was possible to obtain specific information leading to an accurate recording of the feeding practices. The limited statistics in this paper is because the sample size was calculated for the previously published trial and not for this report.

The mothers in this study who were breastfeeding exclusively at six months stated that they would like to continue breastfeeding indefinitely, while those who were not breastfeeding exclusively were uncertain. Successful exclusive breastfeeding may lead to longer breastfeeding. Additionally, positive breastfeeding experiences among first-time mothers imply that they may choose to breastfeed subsequent children (Victora et al 199).

CONCLUSION

This study has addressed the question of when and why low-income, first-time mothers of term LBW infants stop breastfeeding exclusively before the infant is six months old. The barriers to exclusive breastfeeding change between birth and six months and also differ between mothers who receive breastfeeding counselling and those who do not. Mothers need support and information; peer counselling is one component of a breastfeeding support system that needs to be developed into hospital, community and family health programs. Further research needs to be done on how to reinforce exclusivity in breastfeeding, particularly among vulnerable groups such as LBW infants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), InDevelop, the Swedish Institute, Uppsala University, the Philippine Department of Science and Technology , and the University of the Philippines, Manila. We thank Professors Jan Gustafsson and Uwe Ewald of Uppsala University Children’s Hospital for their contribution to the study design. We thank Professor ML Amarillo, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, University of the Philippines, Manila for the

Aghaji MN 00, Exclusive breast-feeding practice and associated factors in Enugu, Nigeria. West Afr J Med 1(1): 66–69.

Agrasada GV, Kylberg E 005, Training peer counsellors in supporting mothers of term low birth weight infants to exclusively breastfeed. Asia Pac Fam Med 5(4): 8–13.

Agrasada GV, Gustafsson J, Kylberg E, Uwe E 005, Postnatal peer counseling on exclusive breastfeeding of low birth weight infants: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Paediatr

94(8): 1109–1115.

Arifeen S, Black RE, Antelman G, Baqui A, Caulfield L Becker S 001, Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory disease and diarrhoea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums.

Pediatr 108(4): E67.

Arlotti JP, Cotrell BH, Lee SH, Curtin JJ 1998, Breastfeeding among low-income women with and without support. J Comm Health Nurs 15(3): 163–178.

Ballard JL, Novak KK, Driver M 1979, A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants. JPediatr

95(5 Pt 1): 769–774.

Binns CW, Scott JA 00, Breastfeeding: reasons for starting, reasons for stopping and problems along the way. Breastfeeding Review 10(): 13–19.

Dewey KG, Cohen R J, Brown KH, Rivera LL 1999, Age of introduction of complementary foods and growth of term, low-birth-weight, breast-fed infants: a randomized intervention study in Honduras. Am J Clin Nutr 69(4): 679–686.

Edmonds K 007, Dewhurst’s Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 7th edn. Wiley-Blackwell, UK.

Eregie CO 001, Observations on water supplementation in breastfed infants. West Afr J Med 0(4): 10–1.

Fahy K, Holshier J 1988, Success or failure in breastfeeding. Aust J Adv Nurs 5(3): 1–18.

Fewtrell MS, Morley R, Abbott RA, Singhal A, Stephenson T, MacFadyen UM, Clements H, Lucas A 001, Catch-up growth in small-for-gestational-age term infants: a randomized trial.

Am J Clin Nutr 74(4): 516–53.

Hong R, Ruiz-Beltran M 008, Low birth weight as a risk factor for infant mortality in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J 14(5): 99–100.

Hörnell A, Hofvander Y, Kylberg E 001a, Solids and formula: association with pattern and duration of breastfeeding. Pediatr

107(3): E38.

Hörnell A, Hofvander Y, Kylberg E 001b, Introduction of solids and formula to breastfed infants: a longitudinal prospective study in Uppsala, Sweden. Acta Paediatr 90(5): 477–48. Jones G, Steketee R, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, Bellagio

Study Group 003, How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 36(9377): 65–71.

Kramer MS, Guo T, Platt RW, Sevkovskaya Z, Dzikovich I, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Chalmers B, Hodnett E, Vanilovich I, Mezen I, Ducruet T, Shishko G, Bogdanovich N 003, Infant growth and health outcomes associated with 3 compared with 6 mo of exclusive breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr 78(): 91-95.

Lucas A, Fewtrell MS, Davies PS, Bishop NJ, Clough H, Cole TJ 1997, Breastfeeding and catch-up growth in infants born small for gestational age. Acta Paediatr 86(6): 564–569. Maninang-Dalisay S, Valdecanas OC, Lipton RL 1986, Breastfeeding

and weaning beliefs and practices among selected mothers in San Pablo City. Philipp J Nutr 39 (4): 48–54.

Martines JC, Ashworth A, Kirkwood B 1989, Breast-feeding among the urban poor in southern Brazil: reasons for termination in the first 6 months of life. Bull World Health Organ 67(): 151–161.

National Statistics Office 2003, National Demographic and Health Survey. NSO, Manila.

Pérez-Escamilla R, Lutter C, Segall AM, Rivera A, Treviño-Siller S, Sanghvi T 1995, Exclusive breast-feeding duration is associated with attitudinal, socioeconomic and biocultural determinants in three Latin American countries. J Nutr 15(): 97–984.

Popkin BM, Adair L, Alin JS, Black R, Briscoe J, Flieger W 1990, Breast-feeding and diarrheal morbidity. Pediatr 86(6): 874–88.

Rao MR, Hediger ML, Levine RJ, Naficy AB, Vik T 2002, Effect of breastfeeding on cognitive development of infants born small for gestational age. Acta Paediatr 91(3): 67–74. Valdecanas OC, Vicente LM, Valera J 1981, Beliefs, attitudes and

the practice of breastfeeding among some urban parturient mothers. Philipp J Nutr 34(1): 8–36.

Victora CG, Huttly SR, Barros FC, Vaughan JP 199, Breastfeeding duration in consecutive offspring: a prospective study from southern Brazil. Acta Paediatr 81(1): 1–14.

World Health Organization 1991, Indicators for Assessing Breast-feeding Practices. WHO, Geneva.

World Health Organization 199, International Statistical Classification

of Diseases and Related Health Problems. WHO, Geneva.

World Health Organization 001, The Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding. A Systematic Review. WHO, Geneva.

World Health Organization 003, Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. WHO, Geneva.

World Health Organization Task Force on Methods for the Natural Regulation of Fertility 1999, The World Health Organization multinational study of breast-feeding and lactational amenorrhea. III. Pregnancy during breast-feeding.

Fertil Steril 7(3): 431–440.

Zohoori N, Popkin BM, Fernandez ME 1993, Breast-feeding patterns in the Philippines: a prospective analysis. J Biosoc Sci

5(1): 17–138.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Grace Agrasada is a pediatrician at the Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila and is the Philippine coordinator of the International Board Certified Lactation Examination. Dr Elisabeth Kylberg is a nutritionist and BFHI coordinator at the Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala University, Sweden.

Correspondence to:

Grace.Agrasada@kbh.uu.se