Placebo-Controlled Comparison of the Selective

Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors Citalopram and

Sertraline*

Stephen M. Stahl

Background:Previous comparative studies of the selec-tive serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have rarely included a placebo control group and have rarely demon-strated significant between-group differences. The study reported on here was a placebo-controlled comparison of the antidepressant effects of two SSRIs, citalopram and sertraline.

Methods:Three hundred twenty-three patients with DSM-IV– defined major depressive disorder were randomized to 24 weeks of double-blind treatment with citalopram (20 – 60 mg/day), sertraline (50 –150 mg/day), or a pla-cebo. The primary efficacy measure was the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) and the primary statis-tical analysis was an analysis of variance comparing the change from baseline to the last observation carried forward in each treatment group.

Results:Both citalopram and sertraline produced signif-icantly greater improvement than placebo on the HAMD, the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale, and the Clinical Global Impression Scale. Significant improve-ment was observed at earlier timepoints in the citalopram group than the sertraline group; however, sertraline treatment was associated with increased gastrointestinal side effects and a tendency toward early discontinuation, and analyses that excluded early dropouts revealed simi-lar acute efficacy for the two active treatments. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale demonstrated a significant anxi-olytic effect of citalopram, but not sertraline, relative to placebo.

Conclusions:This study confirms the antidepressant effi-cacy of two SSRIs, citalopram and sertraline. It is hypoth-esized that the more consistent evidence of antidepressant activity that was observed early in treatment in the citalopram group was related to more pronounced anti-anxiety effects and better tolerability upon initiation of therapy. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:894 –901 ©2000 So-ciety of Biological Psychiatry

Key Words:Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, cita-lopram, sertraline, depression, antidepressants, anxiety

*See accompanying Editorial, in this issue.

Introduction

S

ince the mid-1980s, new classes of antidepressant drugs have emerged that offer improved safety and tolerability profiles compared with previous classes of antidepressant drugs. There are at least seven distinct pharmacologic mechanisms of action for the two dozen or so known antidepressants (Stahl 1998a). Most compara-tive studies of antidepressants, however, have shown similar levels of efficacy (Jonghe and Swinkels 1997). Such findings from large, multicenter trials are at odds with the common clinical experience that some patients respond well to one antidepressant but not to another (Stahl 1998b), even from the same class (Brown and Harrison 1995; Joffe et al 1996; Thase et al 1997, 1999; Zarate et al 1996). Although it is not yet possible to predict which patients will respond to which antidepressants, some recent trials have identified differences in efficacy between antidepressants of differing pharmacologic mech-anisms (e.g., Wheatley et al 1998).Fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, and flu-voxamine are the five currently available selective seroto-nin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) constituting the most widely prescribed class of antidepressants. The lack of demonstrated robust differences in tolerability or efficacy between the SSRIs in head-to-head comparisons is leading formularies to treat these agents as interchangeable, result-ing in denied access and substitutions, a trend that is likely to accelerate as the first SSRIs become generic. On the other hand, the five SSRIs are not members of the same chemical classes and do not share the same secondary binding characteristics (e.g., Stahl 1998b). Failure to demonstrate differences between drugs may be due in part to lack of large-scale, multicenter, placebo-controlled, head-to-head comparisons of two SSRIs.

Citalopram was first marketed in Europe in 1989, is now available in 68 countries worldwide, and is the most recent SSRI to become available in the United States. Because it is the most selective SSRI (Hyttel et al 1995) and has low potential for drug– drug interactions (Green-From the Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of California,

San Diego.

Address reprint requests to Stephen M. Stahl, M.D., Ph.D., University of California, San Diego, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, 8899 University Center Lane, Suite 130, San Diego CA 92122.

Received October 25, 1999; revised May 2, 2000; accepted June 7, 2000.

© 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry 0006-3223/00/$20.00

blatt et al 1998; Jeppesen et al 1996), citalopram theoret-ically could offer advantages over other drugs of this class. Sertraline also has a low potential for drug– drug interac-tions and may have clinically relevant interacinterac-tions with the dopamine transporter (Bolden-Watson and Richelson 1993) and the sigma receptor (Schmidt et al 1989), secondary binding properties that could distinguish it from other SSRIs and offer different advantages over drugs of this class. The study reported here investigated the effi-cacy and safety profiles of citalopram and sertraline in a 24-week, placebo-controlled trial.

Methods and Materials

Eight centers in the United States (see Acknowledgements) participated in this double-blind, prospectively randomized com-parison of citalopram and sertraline with a placebo and each other. Patients of either gender, aged between 18 and 60 years, who satisfied DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria for major depressive disorder with a minimum 2 months duration of illness could be considered for inclusion. Women were eligible only if not pregnant and if taking adequate contraceptive measures. All eligible patients had to score at least 22 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD; Hamilton 1960), have a score of$2 on the depressed mood item and a minimum score of $8 on the Raskin Depression Scale (Raskin et al 1969), together with a lower score on the Covi Anxiety Scale (Covi et al 1981).

Patients were excluded from the study if they 1) presented with another DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis, 2) were taking other psychotropic medication, 3) were at increased risk of suicide (serious suicide attempt in last 12 months or HAMD suicidality item score of$3), 4) were treatment resistant (i.e., had failed to respond to adequate courses of one SSRI or two other pharma-cologically different antidepressants), 5) had a history of sertra-line intolerance or SSRI hypersensitivity reactions, or 6) had a history of alcohol or substance abuse.

Patients who showed a $20% decrease in HAMD-17 item total score during the single-blind placebo lead-in were barred from further participation. The study protocol and consent form were approved by the appropriate institutional review boards. The capacity of the patients to speak, read, write and understand English, to provide written informed consent, and to complete the patient-rated assessments was confirmed during the course of the initial telephone screening, the review of the study proce-dures by the investigator, and the diagnostic interview. In study records, patients were exclusively identified by their initials, screening number, and randomization number.

Study Drug Administration

Having given informed consent, eligible patients began a 1-week, single-blind placebo run-in. Patients who continued to meet entrance criteria at the end of the lead-in period (baseline) were prospectively randomized to 24-weeks treatment with citalopram, sertraline, or placebo.

Dosing began with one capsule/day in the morning with food

for the first week (20 mg citalopram, 50 mg sertraline, or matched placebo) and rose by one capsule/week to three cap-sules/day in the third week (60 mg citalopram, 150 mg sertraline, or placebo). This dose was to be maintained for the duration of the 24-week study; however, for patients intolerant of this dose, a reduction to two capsules/day was allowed. Patients unable to tolerate at least two capsules/day were discontinued. Patients who had difficulty sleeping were permitted chloral hydrate (1000 mg) for no more than 3 days/week for the first 4 weeks. Other psychotropic medication was not allowed.

Assessments

After the screening and baseline assessments, further reviews were undertaken weekly for the first 4 weeks of double-blind treatment, then at the end of weeks 6 and 8, and thereafter at four-week intervals. Depressive symptomatology was assessed at each visit by the 21-item HAMD, Montgomery–Asberg Depres-sion Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery and Asberg 1979), the Clinical Global Impression (Guy 1976) Improvement (CGI-I) and Severity (CGI-S). Additional efficacy data collected at some visits during the study included the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA; Hamilton 1959), the Symptom Checklist-56 (SCL-56; Guy 1976), and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q; Endicott et al 1993).

Tolerability was assessed at each visit by replies to nonleading questions. In addition, a sexual function questionnaire (results to be reported elsewhere) was administered at baseline, week 8, and week 24. Safety assessments included laboratory tests, electro-cardiogram (ECG), vital signs (weight, sitting and standing blood pressure), and a pregnancy test.

Evaluation of Data

The primary efficacy analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT), last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) population. This included any patient randomized to double-blind treatment who took at least one dose of study medication and who had at least one subsequent assessment of efficacy. A secondary anal-ysis was conducted using the subset of patients who completed the initial 8 weeks of double-blind treatment. All statistical tests were two sided and used a 5% significance level. Efficacy variables were analyzed by a two-way analysis of variance with treatment and study center as the two factors. If the treatment-by-center interaction was not significant, then the interaction term was dropped from the statistical analysis. To protect the experimentwise a (.05) against multiple comparisons, pairwise comparisons between treatment groups withp#.05 were treated as statistically significant only if the overall three-group analysis had also yielded a significant treatment effect.

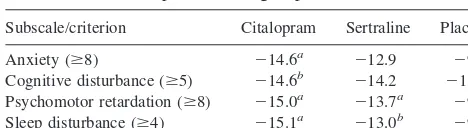

cutoff scores on the HAMD subscales were also used to identify patient subpopulations with more severe symptoms of sleep disturbance ($4), psychomotor retardation ($8), cognitive dis-turbance ($5), and anxiety ($8).

Safety analyses considered all patients who had received at least one dose of study medication. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) included any event that was not present at baseline or, if present at baseline, increased in severity during double-blind treatment. Adverse events were coded by System Organ Class and Preferred Term using a World Health Organi-zation dictionary. Safety assessments included laboratory tests, vital signs, and ECG parameters.

Results

Patient Demographics

There were no clinically relevant differences in demo-graphic variables (Table 1). As is typically found in antidepressant trials, the mean age of the patients was about 40 years, and the majority were female.

Patient Disposition

Each of the eight study sites randomized between 24 and 48 patients to double-blind treatment, resulting in a total of 323 randomized patients, of whom 316 had post-baseline efficacy data and were included in the efficacy analyses.

Approximately 23% (70 of 323; 20% of citalopram pa-tients, 26% of sertraline papa-tients, and 22% of placebo patients) discontinued during the first 8 weeks of double-blind therapy. Forty percent (130 of 323; 44% of citalo-pram patients, 44% of sertraline patients, and 32% of placebo patients) completed the full 24 weeks. Lack of efficacy accounted for 55 discontinuations (8% of citalo-pram patients, 11% of sertraline patients, and 31% of placebo patients), whereas 47 patients discontinued be-cause of adverse events (14% of citalopram patients, 19% of sertraline patients, and 10% of placebo patients).

Efficacy

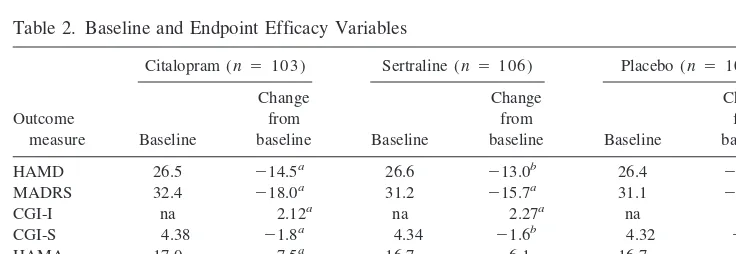

BASELINE COMPARISON. The rating scale scores ob-tained at baseline (Table 2) were indicative of a moder-ately-to-severely depressed patient population and a sim-ilar severity of depressive symptomatology in the three treatment groups.

ENDPOINT COMPARISON. In the endpoint analysis (Table 2), both citalopram and sertraline showed a signif-icant improvement in efficacy compared with placebo; however, the magnitude of the mean improvement in depressive symptoms was numerically greater in the cita-lopram group. This was true for all outcome measures

Table 1. Patient Characteristics

Demographic parameter

Citalopram (n 5 107)

Sertraline (n5 108)

Placebo (n 5 108)

Age (years) 39.1 39.5 37.3

Gender (male/female) 47%/53% 35%/65% 37%/63% Race (white/other) 88%/12% 88%/12% 92%/8%

Weight (kg) 80.0 79.8 79.1

History (recurrent/first episode) 50%/50% 51%/49% 53%/47%

Table 2. Baseline and Endpoint Efficacy Variables

Outcome measure

Citalopram (n5 103) Sertraline (n 5106) Placebo (n5 107)

Baseline

Change from

baseline Baseline

Change from

baseline Baseline

Change from baseline

HAMD 26.5 214.5a 26.6 213.0b 26.4 210.0

MADRS 32.4 218.0a 31.2 215.7a 31.1 211.1

CGI-I na 2.12a na 2.27a na 2.71

CGI-S 4.38 21.8a 4.34 21.6b 4.32 21.2

HAMA 17.0 27.5a 16.7 26.1 16.7 24.8

SCL-56 114 224.4a 116 224.6a 110 214.1

Q-LES-Q 45.1 110.1a 45.3 19.0a 45.6 14.0

HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression Improvement; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression Severity; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; SCL-56, Symptom Checklist-56; Q-LES-Q, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.

except the SCL-56 (Table 2). On the HAMA, significant improvement relative to placebo was observed in the citalopram group but not the sertraline group.

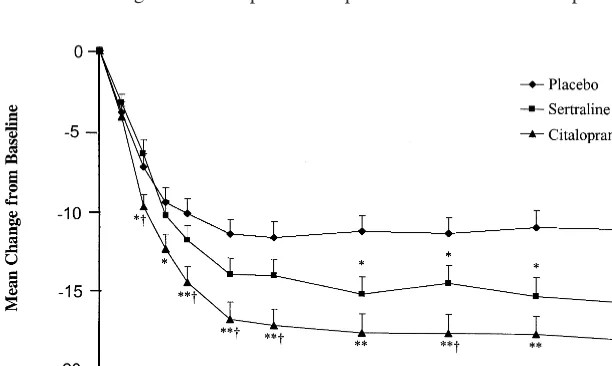

COMPARISON BY VISIT. For citalopram, mean changes from baseline on the HAMD were significant compared with placebo from week 3 until the end of the study (Figure 1). At week 3, however, the overall three-group comparison achieved only borderline significance (p 5 .07). For sertraline, significant differences from

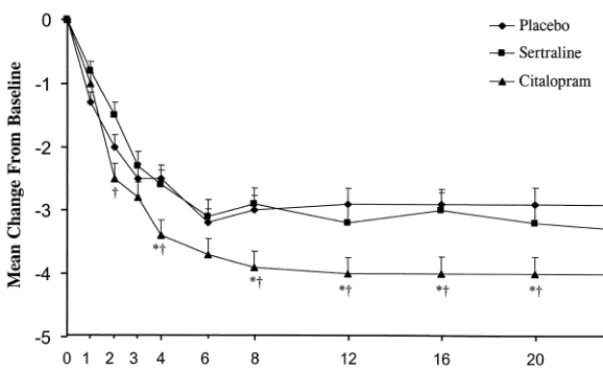

placebo on the HAMD occurred at weeks 12, 20, and 24 (Figure 1). Similar sustained advantages for citalopram over placebo were observed on the MADRS from week 2 (Figure 2). On the CGI-I and CGI-S, significant citalo-pram–placebo differences first appeared at week 2 and week 4, respectively. For sertraline, mean changes from baseline were significant compared with placebo at weeks

12, 20, and 24 for the CGI-S, and at weeks 12, 16, 20, and 24 for the MADRS and CGI-I. A significant treatment-by-center interaction (p , .05) was observed for the

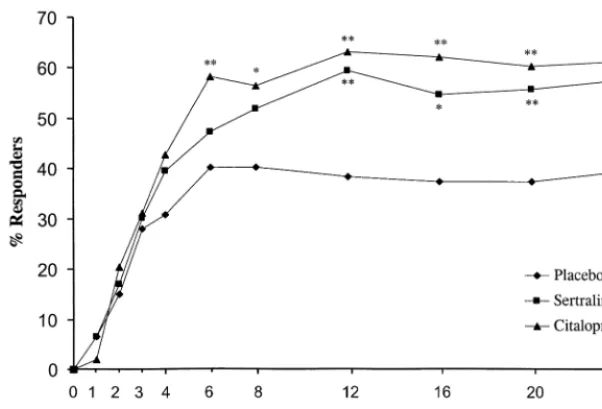

MADRS at week 12 and 16. This interaction was probably attributable to lack of consistency of the sertraline effect across sites, because the sertraline group exhibited numer-ically greater mean improvement than the placebo group at only 5 of the 8 centers at these visits. On the basis of a responder criterion of a 50% decrease from baseline in the HAMD, the response rate in the citalopram group was significantly greater than placebo beginning at week 6, and the response rate in the sertraline group was significantly greater than placebo from week 12 onward (Figure 3). At study endpoint, the percentage of patients with a HAMD-17 total score below 8 was 28% in the placebo group, 37% in the sertraline group, and 45% in the citalopram group. Compared to sertraline, citalopram

Figure 1. Mean change from baseline on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in depressed patients treated with sertraline, citalopram, or a placebo. Error bars repre-sent the SEM. *p,.05 and **p,.01, as

compared with the placebo; †p,.05, as

compared with sertraline.

Figure 2. Mean change from baseline on the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale in depressed patients treated with ser-traline, citalopram, or a placebo. Error bars represent the SEM. *p,.05 and **p,.001,

as compared with the placebo; †p,.05, as

showed significantly greater efficacy in the mean changes from baseline on the HAMD (Figure 1), the CGI-I and the CGI-S at week 2, and the mean change in MADRS at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 16 (Figure 2).

WEEK 8 COMPLETER ANALYSIS. A secondary anal-ysis was conducted on the subset of patients who com-pleted the initial 8 weeks of double-blind treatment, at which point more than 70% of the patients who had initiated each treatment remained in the study. In this analysis, both citalopram and sertraline showed significant efficacy on the HAMD, MADRS, CGI-I, and CGI-S compared with placebo (Table 3).

HAMD SUBFACTORS. The mean change from base-line to endpoint for the HAMD factors and the depressed mood item is shown in Table 4. Both citalopram and sertraline were associated with significantly greater im-provement compared with placebo on all of the symptom

clusters except anxiety, where only citalopram showed a significant effect (Figure 4).

In the subgroups of patients with significant psychomo-tor retardation or insomnia, both citalopram and sertraline showed significant improvement compared with placebo (Table 5). Citalopram, but not sertraline, produced signif-icant improvement in depressive symptomatology among the anxious depressed patients and patients with cognitive disturbance.

Safety

During the 24 weeks of the study, 47 (14.5%) patients discontinued treatment prematurely due to adverse events; 15 (14%) of the citalopram group, 21 (19%) of the sertraline group, and 11 (10%) of the placebo group. More patients discontinued for adverse events in the first 8 weeks from the sertraline group (15%) compared with citalopram and placebo (8% and 7%, respectively). This difference was most apparent during the first week of the study when five patients receiving 50mg/day sertraline,

Figure 3. Percentage response rate in de-pressed patients treated with sertraline, cita-lopram, or a placebo. The responder criterion was a$50% reduction from baseline in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. *p,.05

and **p , .01, as compared with the

placebo.

Table 3. Week 8 Completer Analysis

Outcome measure

Citalopram (n 5 83) change from

baseline

Sertraline (n 578) change from

baseline

Placebo (n 584) change from

baseline

HAMD 215.3b 214.7b 212.2

MADRS 219.2a 217.4b 213.7

CGI-I 2.0b 2.0b 2.4

CGI-S 21.8b 21.7b 21.4

HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression Improvement; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression Severity.

aSignificantly different from placebo,p,.01. bSignificantly different from placebo,p,.05.

Table 4. Mean Change from Baseline on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Subscales

Outcome measure

Citalopram (n5 103)

Sertraline (n 5 106)

Placebo (n 5 107)

Anxiety 24.0a 23.3 22.9

Cognition 23.1b 23.0b 22.2

Melancholia 27.4a 26.9a 25.1

Psychomotor retardation 24.7a 24.3b 23.2

Sleep disturbance 22.2a 21.9b 21.2

Depressed mood item 21.8a 21.6a 21.2

one patient receiving 20mg/day citalopram, and one pa-tient receiving placebo discontinued treatment because of adverse events. All five of the sertraline patients reported nausea, and three also complained of insomnia. Overall, each of the treatments was well tolerated, however, and the mean dose at the end of the study was 57 mg/day in the citalopram group and 143 mg/day in the sertraline group. Similar proportions of patients in each group reported TEAEs: 90.7%, 96.3%, and 88% for citalopram, sertraline, and placebo, respectively. Over the full 24 weeks of the study, six adverse events occurred in at least 10% of citalopram or sertraline patients and with a significantly higher incidence (p,.05) than placebo: nausea,

somno-lence, ejaculation disorder (male patients), increased sweating, anorexia, and decreased libido. All of these adverse events occurred significantly more frequently in both active treatment groups versus placebo with the exception of nausea, which occurred significantly more frequently in sertraline patients only. The vast majority of TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity for all treatment groups.

There were no significant changes in vital signs or ECG parameters except for a clinically meaningless decrease in PR interval (2.9 msec) in the sertraline group. In the two active treatment groups, standing pulse rate was decreased by 1.4 or 1.5 beats/minute at study endpoint. Neither citalopram nor sertraline significantly affected body weight during the 6-month treatment period. Body weight increases $7% of baseline occurred in four sertraline patients (4%), four citalopram patients (4%), and three placebo patients (3%). Decreases in body weight occurred in seven sertraline patients (7%), five citalopram patients (5%), and three placebo patients (3%). The statistically significant mean changes in laboratory parameters that were observed—increased cholesterol with citalopram

(11.6%) and sertraline (13.7%), increased alkaline

phos-phatase (14.5%) with sertraline and decreased uric acid

(26.6%) with sertraline—were small in magnitude and

clinically unimportant.

Discussion

There have been many comparative studies of the SSRIs, but a recent literature review has identified only one published placebo-controlled comparison between SSRIs (Fava et al 1998). Inclusion of a placebo control in studies of approved antidepressants has been commonly avoided, in part because of ethical considerations, but also because of the embarrassingly high rate at which established antidepressant agents fail to separate from placebo. The risk of such presumed Type II errors (“false negatives”) is clearly illustrated by the Fava et al study, in which neither fluoxetine nor paroxetine significantly separated from placebo.

The present 24-week, placebo-controlled study provides clear evidence confirming the antidepressant efficacy of citalopram and sertraline and demonstrates the sustained efficacy of these agents for a period of at least 6 months. The endpoint analysis revealed significant improvement relative to placebo for both active treatment groups on each of the depression rating scales administered. Only the HAMA and the HAMD anxiety subscale failed to detect a significant effect of sertraline in comparison to placebo.

Significant improvement in the citalopram group was consistently observed at earlier timepoints than in the sertraline group. More patients discontinued sertraline treatment because of adverse events at the beginning of the study, and such discontinuations before patients had an opportunity to experience an appreciable therapeutic re-sponse probably decreased the mean improvement

mea-Figure 4. Mean change from baseline on the anxiety subscale of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in depressed patients treated with sertraline, citalopram, or a placebo. Error bars represent the SEM. *p , .01, as compared

with placebo; †p , .05, as compared with

sured in the sertraline group. This conclusion is supported by the results from the week 8 completer analysis, because patients who discontinued early were excluded from this analysis, and the analysis revealed significant improve-ment in sertraline patients as compared to placebo patients. Alternatively, the maximum allowed dose of 150 mg/day sertraline may have been insufficient for some patients; the sertraline maximum recommended dose is 200 mg/day.

The differences between citalopram and sertraline ob-served in this study were not apparent in a previous comparative trial with no placebo control group (Ekselius et al 1997); however, a prior active-controlled study of citalopram and fluoxetine also demonstrated a significant advantage for citalopram after 2 weeks of treatment (Patris et al 1996) and also provided evidence of greater useful-ness of citalopram in the treatment of anxiety symptoms (Bougerol et al 1997). Previous placebo-controlled trials of sertraline have detected significant antidepressant ef-fects of sertraline at an earlier timepoint than was observed in the present study (Lydiard et al 1997; Reimherr et al 1990), and an active-controlled sertraline–fluoxetine com-parison revealed a trend toward greater antianxiety effects of sertraline (Bennie et al 1995).

Given the variability of study populations even among large multicenter trials, the results of the present study may support the conclusion that some patients respond differently to one SSRI than to another, and that different multicenter trials may detect different aspects of this phenomenon, rather than the conclusion that one SSRI is clearly superior to another in a manner that is generaliz-able to the wide population of patients who take antide-pressants. These results also support the anecdotal obser-vations of clinicians that different patients have optimal efficacy on different SSRIs, and argue for keeping the broadest prescribing options open for clinicians to be able to match the best agent with the best therapeutic outcome for each individual patient.

Although all of the SSRIs share a presumed primary mechanism of action, their individual postsynaptic binding characteristics, pharmacokinetic profiles, and other sec-ondary pharmacologic properties may be clinically rele-vant (Stahl 1998b). Participants in the trial discussed here

included a relatively homogenous group of moderate-to-severe outpatients with uncomplicated first-episode or recurrent major depressive disorder. Studies conducted in a broader range of depression subpopulations could be of use in delineating the clinical factors that determine the optimal match between an individual patient profile and an antidepressant’s pharmacologic profile, even within the SSRI class.

Coinvestigators for this multicenter trial were John Carman, Lorna Charles, Eugene Duboff, James Ferguson, James Hartford, Ram Shriv-astava, and Charles Wilcox. All coinvestigators, including the author, received research grant support from Forest Laboratories for this trial. The author is a consultant, lecturer, and recipient of research grants from Forest Laboratories and H. Lundbeck A/S, the companies that market citalopram. The author is also a consultant, lecturer, and recipient of research grants from Pfizer Inc., the company that markets sertraline. The author thanks John Rush and Bruce Pollock for their valuable comments on the draft manuscript.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994):Diagnostic and Sta-tistical Manual of Mental Disorders,4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Bech P, Allerup P, Gram LF, Reisby N, Rosenberg R, Jacobsen O, Nagy A (1981): The Hamilton Depression Scale: Evalua-tion of objectivity using logistic models. Acta Psychiatr Scand63:290 –299.

Bennie EH, Mullin JM, Martindale JJ (1995): A double-blind multicenter trial comparing sertraline and fluoxetine in out-patients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 56:229 – 237.

Bolden-Watson C, Richelson E (1993): Blockade by newly developed antidepressants of biogenic amine uptake into rat brain synaptosomes.Life Sci52:1023–1029.

Bougerol T, Scotto J-G, Patris M, Strub N, Lemming O, Petersen HEH (1997): Citalopram and fluoxetine in major depression: Comparison of two clinical trials in a psychiatrist setting and in general practice.Clin Drug Invest14:77– 89.

Brown WA, Harrison W (1995): Are patients who are intolerant of one selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor intolerant to another?J Clin Psychiatry56:30 –34.

Covi L, Rickels K, Lipman RS, McNair DM, Smith VK, Downing R, et al (1981): Effects of psychotropic agents on primary depression.Psychopharmacol Bull17:100 –101. Ekselius L, von Knorring L, Eberhard G (1997): A double-blind

multicenter trial comparing sertraline and citalopram in pa-tients with major depression treated in general practice. Int Clin Psychopharmacol12:323–331.

Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R (1993): Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: A new mea-sure.Psychopharmacol Bull29:321–326.

Fava M, Amsterdam JD, Deltito JA, Salzman C, Schwaller M, Dunner DL (1998): A double-blind study of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and placebo in outpatients with major depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry10:145–150.

Table 5. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Mean Change from Baseline in Depression Subgroups

Subscale/criterion Citalopram Sertraline Placebo

Anxiety ($8) 214.6a 212.9 29.9

Cognitive disturbance ($5) 214.6b 214.2 211.1

Psychomotor retardation ($8) 215.0a 213.7a 29.8

Sleep disturbance ($4) 215.1a 213.0b 29.3

Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, Harmatz JS, Shader RI (1998): Drug interactions with newer antidepressants: Role of human cytochromes P450.J Clin Psychiatry59(suppl 15):19 –27. Guy W (1976): ECDEU Assessment for Psychopharmacology,

Revised, DHEW Publication (ADM). Rockville, MD: Na-tional Institute of Mental Health.

Hamilton M (1959): The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol32:50 –55.

Hamilton M (1960): A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry23:56 – 62.

Hyttel J, Arnt J, Sanchez C (1995): The pharmacology of citalopram.Rev Contemp Pharmacother6:271–285. Jeppesen U, Gram LF, Vistisen K, Loft S, Poulsen HE, Brosen K

(1996): Dose-dependent inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 by citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine.Eur J Clin Pharmacol51:73–78.

Joffe RT, Levitt AJ, Sokolov ST, Young LT (1996): Response to an open trial of a second SSRI in major depression. J Clin Psychiatry57:114 –115.

Jonghe F, Swinkels J (1997): Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Relevance of differences in their pharmacological and clinical profiles.CNS Drugs7:452– 467.

Kerr JS, Sherwood NJ, Hindmarch I (1991): The comparative psychopharmacology of 5HT re-uptake inhibitors.Hum Psy-chopharmacol6:313–317.

Lydiard RB, Stahl SM, Hertzman M, Harrison WM (1997): A double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing the effects of sertraline versus amitriptyline in the treatment of major depression.J Clin Psychiatry58:484 – 491.

Montgomery SA, Asberg M (1979): A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change.Br J Psychiatry134:382– 389.

Patris M, Bouchard J-M, Bougerol T, Charbonnier J-F, Chevalier J-F, Clerc G, et al (1996): Citalopram versus fluoxetine: A double-blind, controlled, multicentre, phase III trial in

pa-tients with unipolar major depression treated in general practice.Int Clin Psychopharmacol11:129 –136.

Raskin A, Schulterbrandt J, Rectig N, McKeon JJ (1969): Replication of factors of psychopathology in interview, ward behaviour, and self-report ratings of hospitalised depressives. J Nerv Ment Dis148:87–98.

Reimherr FW, Chouinard G, Cohn CK, Cole JO, Itil TM, LaPierre YD, et al (1990): Antidepressant efficacy of sertra-line: A double-blind, placebo- and amitriptyline-controlled, multicenter comparison study in outpatients with major de-pression.J Clin Psychiatry51(suppl B):18 –27.

Schmidt A, Lebel L, Koe BK, Seeger T, Heym J (1989): Sertraline potently displaces 3H-(1)-3-PPP binding to sigma sites in rat brain.Eur J Pharmacol165:335–336.

Stahl SM (1998a): Basic psychopharmacology of antidepressants (part 1): Antidepressants have seven distinct mechanisms of action.J Clin Psychiatry59(suppl 4):5–14.

Stahl SM (1998b): Not so selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry59:343–344.

Thase ME, Blomgren SL, Birkett MA, Apter JT, Tepner RG (1997): Fluoxetine treatment of patient with major depressive disorder who failed initial treatment with sertraline. J Clin Psychiatry58:16 –21.

Thase ME, Lydiard B, Feighner J (1999, May): Citalopram treatment of fluoxetine nonresponders. Presented at the an-nual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Wash-ington, DC.

Wheatley DP, van Moffaert M, Timmerman L, Kremer CME (1998): Mirtazapine: Efficacy and tolerability in comparison with fluoxetine in patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder.J Clin Psychiatry59:306 –312. Zarate CA, Kando JC, Tohen M, Weiss MK, Cole JO (1996):