CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.1. Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL)

In daily life, we use language to many functions, for instance talking to other people, reading a book, and speaking in the front of the audience. To do those activities, we need a language and should know its context of situation where we use the language. An understanding about language that we are used either spoken or written is analyzed by Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL). Its main concern is the function of language in the society.

Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) is an approach to linguistics that considers language as a social semiotic system. It was developed by Michael Halliday, who took the notion of system from his teacher, J. R. Firth. SFL places the function of a language as central (what language does, and how it does). SFL is successfully applied for analysis of texts of different genres and with different purposes. It provides some universal tools for analyzing texts in order to identify what makes a text and the kind of text it is, one of them is grammatical intricacy and lexical density.

The word text is used in linguistics to refer to any passage, spoken or written. A text both spoken and written has a context of situation and it concluded in SFL perspective. A context of situation can be specified through use of the register variables: field, tenor and mode. (Gerrot and Peter, 1994:11).

1. Field refers to what is going on, including activity focus (nature of social activity) and object focus (subject matter). So field specifies what’s going on

2. Tenor refers to the social relationships between those taking part. These are specifiable in terms of status or power (agent roles, peer or hierarchic relations), affect (degree of like, dislike or neutrality) and contact (frequency, duration and intimacy of social contact).

3. Mode refers to how language is being used, whether the channel of communication is spoken or written and language is being used as a mode of action or reflection.

Knapp and Megan (2005:18) give examples about context of situation, they are:

Table 1. Context of situation: casual, brief encounter between two friends in the street

What (field/ideational meaning) Shared experiences/ inconsequential subject matter

Who (tenor/interpersonal meaning) Roughly equal How (mode/textual meaning) Spoken, informal

Table 2. Context of situation: teacher job interview

What (field/ideational meaning) Educational (technical), questions pre-planned

Who (tenor/interpersonal meaning) Unequal, interviews have more power How (mode/textual meaning) Spoken, formal

A situation where we use spoken language are typically interaction situation, do not usually deliver monologues to ourselves, although we do often interact with ourselves by imagining a respondent our markers. In most spoken situation is face-to-face contact with the interactant, and very typically using language to achieve some ongoing social action.

with audience. SLF claims is much more than that: it is that this analysis of the situation tells something significant about how language will be used.

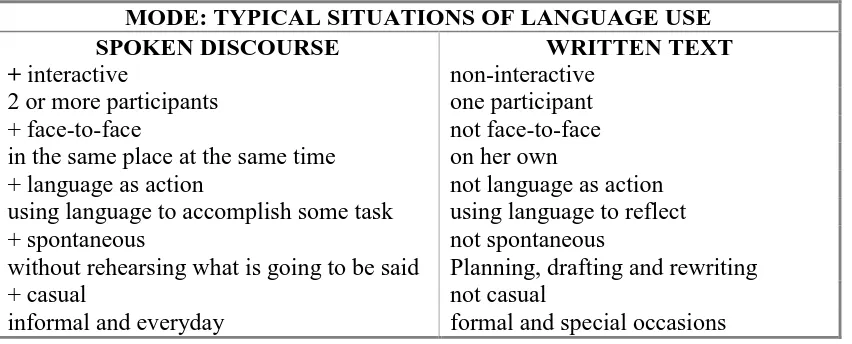

There are some very obvious implications of the contrast between spoken and written modes. Certain linguistic patterns correspond to different positions on the mode continua. (Eggins, 2004:92).

Table 3. Mode: characteristics of spoken and written language situations MODE: TYPICAL SITUATIONS OF LANGUAGE USE

SPOKEN DISCOURSE WRITTEN TEXT

+ interactive non-interactive

2 or more participants one participant

+ face-to-face not face-to-face

in the same place at the same time on her own

+ language as action not language as action

using language to accomplish some task using language to reflect

+ spontaneous not spontaneous

without rehearsing what is going to be said Planning, drafting and rewriting

+ casual not casual

informal and everyday formal and special occasions

Source: An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics 2nd Edition

(Eggins:2004)

Table 4. Characteristic features of spoken and written language SPOKEN and WRITTEN LANGUAGE

(false starts, hesitations, interruptions, overlap, incomplete clauses)

‘final draft’ (polished) indications of earlier drafts removed

everyday lexis ‘prestige’ lexis

non-standard grammar standard grammar

grammatical complexity grammatical simplicity

lexically sparse lexically dense

Source: An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics 2nd Edition

From the tables above can be understand the difference mode of spoken and written language and the grammatical intricacy and the lexical density refer to both spoken and written language use. Eggins (2004:20) states that systematic functional linguistic described as a functional-semantic approach to language which explores both how people use language in different contexts, and how language is structured for use as a semiotic system.

2.2. Grammatical Intricacy

Grammatical intricacy refers to the complexity of language in a text. Francesconi (2014:55) states that grammatical intricacy regards the complexity of language in terms of how many clauses are joined in a clause complex and intricacy arises as a result of the ways in which clauses are strung together. According to Eggins (2004:97) grammatical intricacy relates to the number of clauses per sentence, and can be calculated by expressing the number of clauses in a text as a proportion of the number of sentences in the text. To identify grammatical intricacy used formula is:

Grammatical intricacy = total number of clauses

(Eggins, 2004:97)

text has high grammatical intricacy, it means the text is difficult to understand because many clauses per sentence.

2.3. Lexical Density

In a writing language, the term of lexical density influence a text, it helps to identify the level of words complexity. The term of lexical density is used in a text analysis for describing the proportion of lexical items or content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) to the total number of words. (Johansson, 2008:65). It also is necessary to distinguish grammatical words or function words (pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliary verbs, and some adverbs) from lexical items and the differences between them. (Cindy and James, 2007; Halliday, 1985b in To, 2013:62). Halliday (1993:76) state that lexical density is a measure of the density of information in any passage of a text, according to how tightly the lexical items (content words) have been packed into the grammatical structure and the content words are most important for explaining information. Bellow are examples of lexical density. The lexical words are in bold type; lexical density count is given at the right: (a) My father used to tell me about a singer in his village. 4 (b) A parallelogram is a four-sided figure with its opposite sides parallel. 6

(Halliday, 1993:76)

To identify lexical density used Ure’s formula is:

Lexical density =number of lexical items x %

Regarding this measurement, if the number surpasses forty per cent, it accounts for higher lexical density, otherwise of reading difficulty. Ure’s study showed that the lexical density for the spoken texts was under 40% and for the written texts 40% and over. In a text if the number of grammatical words are higher than the number of lexical items, it makes the level of lexical density is low, so the text is difficult to read and influence the understanding of the text.

A text in English with high lexical density is easy to understand. On the contrary a text with low density is difficult to understand. According to Halliday (2002:328) the written language version has a much higher lexical density; at the same time, it has a much simpler sentential structure.

Table 5. Spoken and written language (Eggins, 2004:98)

Spoken Language Written Language

Low lexical density

Few content carrying words as a proportion of all words

High lexical density

Many content carrying words as a proportion of all words

2.4. Clause

In a grammar, a clause is the smallest grammatical unit that can express a complete preposition. Clause is a group of words which forms a part of a sentence and contains a subject and a predicate where the predicate is typically a verb phrase – a verb together with any objects and other modifiers, for example “My sister plays the oboe.” According to Knapp and Watkins (2005:45) the clause is the basic grammatical unit in a sentence and a main clause is a clause that can stand alone as a complete sentence. The number of clauses and the relationship between them in a sentence is the basis for distinguishing types of sentences (simple, compound and complex sentence).

2.4.1. Independent Clause

An independent clause is a clause that can stand on itself. It does not need to be joined to any other clauses, because it contains all the information necessary to be a complete sentence. The independent clause contains a subject and a predicate; it makes sense by itself and therefore expresses a complete thought. For example, Jims reads. “Jims” is the subject and “reads” is the action or verb.

a. Independent Clause: Non-Elliptical vs Elliptical

Non-Elliptical Elliptical

Who is the best man? Michael Jones (is the best man) Are they having a reception? Yes (they are having a reception) Joanne’s mother began to cry and (she) was handed a hanky

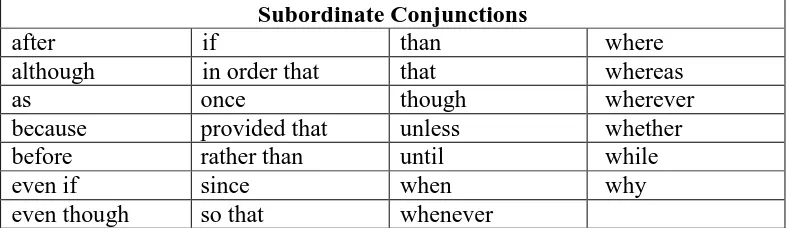

In the elliptical examples above, known that Michael Jones is the best man, not the captain of the local cricket team, because ‘is the best man’ is recoverable information, but which cannot stand alone as a sentence. Some grammarians use the term subordinate clause as a synonym for dependent clause. A dependent clause will begin with a subordinate conjunction or a relative pronoun and will contain both a subject and a verb. This combination of words will not form a complete sentence. It will instead make a reader want additional information to finish the thought. Below is a list of subordinate conjunctions and relative pronouns.

Table 6. Subordinate conjunctions

Subordinate Conjunctions

after if than where

although in order that that whereas

as once though wherever

because provided that unless whether

before rather than until while

even if since when why

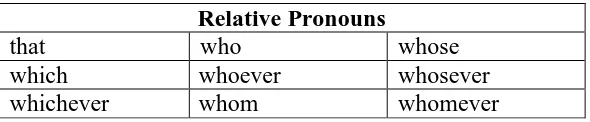

Table 7. Relative pronouns

Relative Pronouns

that who whose

which whoever whosever

whichever whom whomever

There are some different types of dependent clauses include noun clauses, relative (adjectival) clauses, and adverbial clauses. (Knapp and Megan, 26:2005). 1. Noun clause

A noun clause consists of a subject and predicate that functions as a noun. One of its most common functions is as the object of a verb, especially of a verb asserting or mental activity. If such a verb is the in past tense, the verb in the noun clause object takes past form also.

Example: That coffee grows in Brazil is well known to all.

2. Relative (adjectival) clauses

A clause that gives additional information about a noun or noun group is known as an adjectival or relative clause, and is said to be ‘embedded’ as the information it provides is embedded or located within the subject or object of another clause. The generally begin with a relative pronoun such as who, which or that.

Example: Subject: He paid the money to the man who had done the work. Object: All playgrounds need rules that people should obey.

3. Adverbial clause

and result to what is happening in the main clause. Adverbial clause consist of a subject and predicate introduced by a subordinate conjunction like when, although, because, if.

Example: Time: When children first arrive at school they need to know what to do.

Concession: Although there are other parks nearby there are none close to the shopping centre.

Reason: New traffic lights have been installed near the school because of the heavy traffic flow.

a. Dependent Clauses: Embedded vs Non-Embedded

Remember not to disturb any flora or fauna that you may see as they are protected by law.

The following provides a diagrammatical representation:

SENTENCE

MAIN CLAUSE

S V O

(You) Remember not to disturb any flora or fauna

EMBEDDED CLAUSE DEPENDENT CLAUSE

S V S V A that you may see as they are protected by law

Figure 1. An example of embedding clause (Knapp and Watkins: 2005)

Non-embedded : It’s my own invention-to keep sandwiches in Embedded : I needed something ((to keep sandwiches in))

In the first example-to keep sandwiches in is not embedded. Instead, it is a dependent clause, one which adds a kind of afterthought. In the second, ((to keep sandwiches in)) is embedded, and therefore, does not function as a dependent clause in its own right, but rather acts more like a word qualifying the meaning of ‘something’.

Non-embedded : The prisoner, who hid in the ticket, escaped.

Embedded : The prisoner who hid in the ticket escaped, but his accomplice was recaptured.

The first who hid in the ticket is not embedded; it is a dependent clause which adds more information about the event under discussion. There are two pieces of information in this clause complex: ‘The prisoner escaped’ and ‘said prisoner hid in the ticket’. In the second clause complex who hid in the ticket is embedded. This embedded bit serve to define which prisoner it was who hid in the ticket to distinguish this prisoner from some other. In this example there are again two pieces of information, but they are as follows: ‘The prisoner who hid in the ticket escaped,’ and ‘his accomplice was recaptures.’

2.4.3. Clause Complex

clauses are linked together in certain systematic and meaningful ways. When we write clause complexes down, either from speech or composed in written language, we generally show clause complex boundaries with full stops. More complex sentences may contain multiple clauses. Gerot and Peter (1994:82) give an example of a clause and a clause complex, as following:

“John invited the Wilsons to the party but they did not come which made John rather indignant as he had thought he was doing them a favour.”

This text comprises one sentence, but five clauses:

John invited the Wilsons to the party

but they did not come

which made John rather indignant

as he had thought

he was doing them a favour.

These five clauses together comprise a clause complex.

2.5. Sentence

1. Simple sentence

A simple sentence, also called an independent clause, contains a subject and a verb, and it expresses a complete thought. Takes form of:

a. A statement. Example: He lives in New York.

b. A question. Example: How old are you?

c. A request. Example: Please close the door.

d. An exclamation. Example: What a terrible temper she has!

2. Compound sentence

A compound sentence contains two or more sentences joined into one by:

a. Punctuation alone. Example: The weather was very bad; all classes were canceled.

b. Punctuation and a conjunctive verb. Example: The weather was very bad; therefore all classes were canceled.

c. A coordinate conjunction (and, or, but, yet, so, for). Example: The weather was very bad, so all classes were canceled.

3. Complex sentence

A complex sentence contains one or more dependent (or subordinate) clauses. A dependent clause contains a full subject and predicate beginning with a word that attaches the clause to an independent clause (called the main clause). A complex sentence always has a subordinator such as because, since, after,

although, or when (and many others) or a relative pronoun such as that, who, or

which.

b. Adjective clause. Example: Here is a book which describes animals.

c. Noun clause. Example: That coffee grows in Brazil is well known to all.

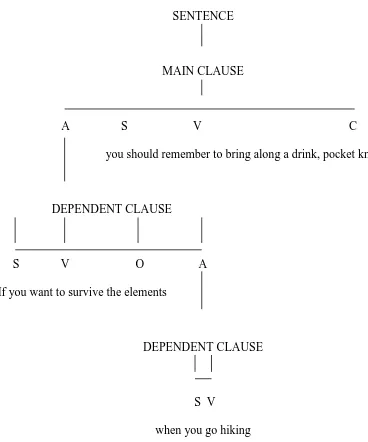

Knapp and Watkins (2005:65) state that in a sentence there can be levels of complexity within complex sentences. Within a dependent clause, for instance, there can be another dependent clause. For example, in the following complex sentence there is a main clause (in bold), a dependent clause in an adverbial relationship with the main clause (in italics), and a dependent clause (underlined italics) in an adverbial relationship with the first dependent clause.

This complex structure with the diagram below:

SENTENCE

MAIN CLAUSE

A S V C

you should remember to bring along a drink, pocket knife etc.

DEPENDENT CLAUSE

S V O A If you want to survive the elements

DEPENDENT CLAUSE

S V when you go hiking

Figure 2. An example of complex structure. (Knapp and Watkins: 2005)

4. Compound-complex sentence (complex-compound sentence)

Example: All classes were canceled because the weather was bad, and students were told to listen to the radio to find out when classes would begin again.

2.6. Related Studies

Vinh To (2013) in his journal article entitled Lexical Density and Readability: A Case Study of English Textbooks examines the lexical density and readability of four texts from English text books known as Active Skill for Reading at elementary, pre-intermediate, intermediate and upper-intermediate levels. Vinh To applies three methods in determining lexical density and readability as proposed by Halliday, Ure, and Flesch. Halliday’s method and Ure’s method used to measure lexical density exploration in texts, while Flesch’s method is reading ease scale. The analysis

revealed that three of the four reading texts were of a high lexical density, apart from the text for upper-intermediate level. There was little evidence of an increase of lexical density and readability in accordance with the increase of text levels as well as little indication relating to the connections between text levels, readability and lexical density. This journal provides general understanding about lexical density and its relationship to readability so it helps the writer in understanding method of Halliday and Ure in lexical density and readability.

Liliek Soepriatmadji (2011) in his paper entitled Lexical Density dan Grammatical Intricacy Materi Bacaan pada Buku Bahasa Inggris Kelas 6 SD

understood that although a text is written in complex sentences but sometime the text can be understood by the reader. Thus, from his paper the writer knows how to make a conclusion about grammatical intricacy and lexical density in a text.