AUSTIN J. FREELEY Late, John Carroll University

DAVID L. STEINBERG University of Miami

Argumentation and Debate

Critical Thinking for Reasoned

Decision Making

T W E L F T H E D I T I O N

Australia•Brazil•Japan•Korea•Mexico•Singapore•Spain•United Kingdom•United States

Printed in the United States of America

Cover Image: © Imagemore Co., Ltd.

© 2009, 2005 Wadsworth Cengage Learning

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored, or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at

Cengage Learning Academic Resource Center 1-800-423-0563

For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all requests online at

www.cengage.com/permissions. Further permissions questions can be e-mailed to

Library of Congress Control Number: 2007941012

ISBN-13: 978-0-495-09590-3

Cengage Learning products are represented in Canada by Nelson Education, Ltd.

For your course and learning solutions, visitacademic.cengage.com

Purchase any of our products at your local college store or at our preferred online storewww.ichapters.com

To Dr. Austin J. Freeley and Trudy.

Brief Contents

Chapter 1 Critical Thinking 1

Chapter 2 Applied and Academic Debate 19 Chapter 3 Stating the Controversy 43 Chapter 4 Analyzing the Controversy 60 Chapter 5 Exploring the Controversy 86 Chapter 6 Evidence 105

Chapter 7 Tests of Evidence 126

Chapter 8 The Structure of Reasoning 152 Chapter 9 Types of Reasoning 169

Chapter 10 Obstacles to Clear Thinking 188 Chapter 11 Requirements of the Case 204 Chapter 12 Building the Affirmative Case 214 Chapter 13 Building the Negative Case 235 Chapter 14 Refutation 261

Chapter 15 Presenting the Case: Composition 280 Chapter 16 Presenting the Case: Delivery 300 Chapter 17 Evaluating the Debate 314

Chapter 18 Academic Debate Formats and Cross-Examination 332

Chapter 19 Applied Parliamentary Debate 356

Contents

PREFACE xi

Chapter 1 Critical Thinking 1

I. Debate 6

II. Individual Decisions 9 III. Group Discussion 11 IV. Persuasion 12 V. Propaganda 13 VI. Coercion 14

VII. Combination of Methods 15 VIII. Ethical Decision Making 16 Exercises 17

Chapter 2 Applied and Academic Debate 19

I. Applied Debate 20 II. Academic Debate 24

III. Ethical Standards for Debate 38 Exercises 41

Chapter 3 Stating the Controversy 43

I. Defining the Controversy 45 II. Phrasing the Debate Proposition 45 III. Presumption and Burden of Proof 48

IV. Types of Debate Propositions 55 Exercises 58

Chapter 4 Analyzing the Controversy 60

I. The Importance of Defining Terms 61 II. Methods of Defining Terms 63 III. Issues 72

Exercises 84

Chapter 5 Exploring the Controversy 86

I. Brainstorming for Ideas 87 II. Locating Materials 88 III. Reading with a Purpose 98 IV. Reading Critically 99 V. Recording Materials 99 VI. Organizing Materials 102 Exercises 104

Chapter 6 Evidence 105

I. Sources of Evidence 108 II. Types of Evidence 112

III. The Probative Force of Evidence 122 Exercises 125

Chapter 7 Tests of Evidence 126

I. Uses of Tests of Evidence 126 II. Tests of Credible Evidence 129 III. Tests of Audience Acceptability 145 Exercises 150

Chapter 8 The Structure of Reasoning 152

I. The Classical Structures 152

II. The Elements of Any Argument 163

III. Extending the Elements of An Argument 167 Exercises 168

Chapter 9 Types of Reasoning 169

I. The Degree of Cogency 169

II. Tests of Reasoning and Their Uses 173

III. General Tests of Reasoning 174

IV. Types of Reasoning and Tests for Each Type 174 Exercises 187

Chapter 10 Obstacles to Clear Thinking 188

I. Fallacies of Evidence 190 II. Fallacies of Reasoning 191 III. Fallacies of Language 193 IV. Fallacies of Pseudoarguments 195 Exercises 202

Chapter 11 Requirements of the Case 204

I. Requirement to Present a Prima Facie Case 205 II. General Case Requirements 207

Exercises 212

Chapter 12 Building the Affirmative Case 214

I. Objectives of the Affirmative Case 216 II. Proposition of Value Affirmative Cases 216 III. Proposition of Policy Affirmative Cases 219 IV. Building for Optimum Capability 231 V. Alternative Debate Approaches 233 Exercises 233

Chapter 13 Building the Negative Case 235

I. Objectives of the Negative Case 235 II. Proposition of Value Negative Cases 237 III. Proposition of Policy Negative Approaches 240 Exercises 260

Chapter 14 Refutation 261

I. Shifting the Burden of Rebuttal 261 II. Purpose and Place of Refutation 262 III. Preparing for Refutation 263

IV. Arranging Material for Refutation 265 V. Selecting Evidence and Reasoning 265 VI. The Structure of Refutation 271 VII. Methods of Refutation 278 Exercises 279

Chapter 15 Presenting the Case: Composition 280

I . Analysis of the Audience 280 II. Written and Oral Styles 285 III. A Philosophy of Style 286

IV. Factors of Style in Speech Composition 287 V. Rhetorical Factors in Speech Composition 291 VI. Editing 298

Exercises 299

Chapter 16 Presenting the Case: Delivery 300

I. Methods of Delivery 300 II. Steps to Good Delivery 305 III. Nonverbal Communication 306

IV. Special Considerations: Tournament Debate Delivery 311 Exercises 313

Chapter 17 Evaluating the Debate 314

I. Functions of the Judge 314 II. Judging Philosophies 320 III. Functions of the Ballot 329

IV. Special Ballots for Special Purposes 330 Exercises 331

Chapter 18 Academic Debate Formats and Cross-Examination 332

I. Formats of Debate 332 II. The Audience 350

III. Adapting the Debate to Communications Media 352 Exercises 355

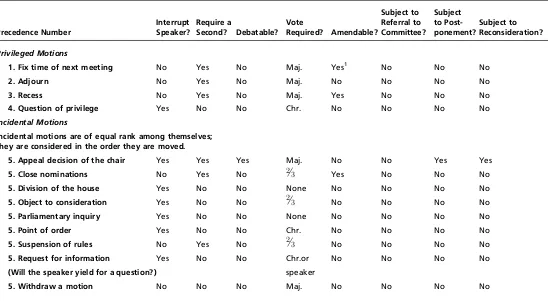

Chapter 19 Applied Parliamentary Debate 356

I . Sources of Parliamentary Debate Rules 357 II. The Order of Business 358

III. Presentation of Motions 359 IV. Precedence of Motions 360 V. Purposes of Motions 360 VI. Unanimous Consent 365 Exercises 365

APPENDIX A: A PRESIDENTIAL DEBATE 368

APPENDIX B: NATIONAL CHAMP IONSHI P D EBATE 404

APPENDIX C: NATIONAL INTERCOLLE GIATE DEBATE

PROPOSITIONS (NDT) 458

APPENDIX D: NATI ONAL INTERCOLLEGI ATE DEBATE

PROPOSITIONS (CEDA) 469

APPENDIX E: DEBATE BIBLIOGRAPHY 475

APPENDIX F: GLOSSARY OF TERMS IN ARGUMENTATION AND

DEBATE 503

INDEX 513

Preface

N

ow more than ever, debate is popular. During the 2008 election cycle, more than 40 televised debates involving the candidates for president and vice president will help to inform the voting public about the policies and per-sonalities of the competing debaters. Election campaigns at every level, from lo-cal to national offices, routinely involve formal debates. The Urban Debate League movement has expanded local public school participation in competitive debate, and international efforts have encouraged the growth of debate around the globe. Academic debate on campuses is vibrant, and students get in line to take debate courses.The twelfth edition of Argumentation and Debatecontinues the features that have led to its wide use by “generations” of students for over 50 years, while

reflecting the newest trends and knowledge in the practice and study of argu-mentation and debate. To that end, David L. Steinberg continues to build upon the groundbreaking work of Austin J. Freeley, the author of the first nine editions. Dr. Freeley passed away on January 14, 2005. His words form the foun-dation of this book and the inspiration for its evolution. Although the funda-mental nature of educational debate was established in classical times by Aristotle, Protagoras, and the scholars who followed them through the ages, con-temporary debate continues to change and evolve at an ever-increasing rate. Along with many updates and revisions, this edition provides timely material on:

■ Concept Boxes (key concepts set aside in boxes in bulleted lists or key word

format)

■ Updated examples

■ References to new research about debate and argumentation ■ Addition of new and tested classroom exercises

■ Expanded discussion of ethical decision making ■ Description of the research process in the wired era

■ Explanation of performance as argumentation

■ Updated presidential debate (2004) and expanded discussion of political

de-bates through the “YouTube” debates of 2007

■ Expanded links to debate resources ■ Expanded bibliography

■ “Flowcharts”identifying Speaker duties in Policy and Value Debate Formats

Most chapters provide a miniglossary of terms and conclude with a set of sug-gested exercises designed to provide experiential learning of the chapter’s

con-cepts. Throughout the text many important materials are presented in insets that we hope will prove helpful to the student.

This book is designed for all who seek to improve their critical thinking, reasoned decision making, and advocacy skills. In particular this text is designed for the undergraduate course in argumentation and debate. It is appropriate for any course that empowers students as active citizens participating in the societal demands of democracy.

Austin J. Freeley recorded his thanks to his professors, mentors, and friends in the first edition of this book. The memory of their contributions is luminous across the years.

David L. Steinberg would like to record his thanks to his debate mentors, David Thomas, Norma Cook, Jim Brooks, Warren Decker, and Brenda Logue, and his terrific assistant coaches for teaching him far more than he could teach them. His sincere thanks go to each of them, including Dan Leyton, Dale Reed, Ernie Quierido, David Cram-Helwich, Christopher Cooper, Nicole Colston, Gavin Williams, Matt Grindy, Nicole Richter, Kenny McCaffrey, and Johnny Prieur. Johnny’s work inspired and informed the updates on research and

evi-dence organization in Chapter 5.

He would also like to acknowledge his boys, Adam and John, who make him very proud, and his supportive and caring wife, Victoria, with much love.

Steinberg is grateful to Dr. Freeley for giving him the opportunity to con-tribute to this project and, thus, to be a small part of his tremendous legacy.

Thanks to all the wonderful people at Cengage who work hard to make this book a reality, including Kimberly Gengler, Monica Eckman, Jessica Rasile, and Smitha Pillai, who are exceptionally patient, professional, and understanding.

Finally, thanks to the many students we have taught and judged over the years, and those who will carry the tradition into the future. They are our inspi-ration, helping us refine our thinking and develop more cogent statements on many matters, and have provided many of the examples found throughout this text.

David L. Steinberg

1

Critical Thinking

A

fter several days of intense debate, first the United States House of Representatives and then the U.S. Senate voted to authorize President George W. Bush to attack Iraq if Saddam Hussein refused to give up weapons of mass de-struction as required by United Nations’s resolutions. Debate about a possiblemili-tary action against Iraq continued in various governmental bodies and in the public for six months, until President Bush ordered an attack on Baghdad, beginning Operation Iraqi Freedom, the military campaign against the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein. He did so despite the unwillingness of the U.N. Security Council to sup-port the military action, and in the face of significant international opposition.

Meanwhile, and perhaps equally difficult for the parties involved, a young cou-ple deliberated over whether they should purchase a large home to accommodate their growing family or should sacrifice living space to reside in an area with better public schools; elsewhere a college sophomore reconsidered his major and a senior her choice of law school, graduate school, or a job. Each of these situations called for decisions to be made. Each decision maker worked hard to make well-reasoned decisions.

Decision making is a thoughtful process of choosing among a variety of options for acting or thinking. It requires that the decider make a choice. Life demands de-cision making. We make countless individual dede-cisions every day. To make some of those decisions, we work hard to employ care and consideration; others seem to just happen. Couples, families, groups of friends, and coworkers come together to make choices, and decision-making bodies from committees to juries to the U.S. Congress and the United Nations make decisions that impact us all. Every profession requires effective and ethical decision making, as do our school, community, and social organizations.

We all make many decisions every day. To refinance or sell one’s home, to buy a high-performance SUV or an economical hybrid car, what major to select, what to have for dinner, what candidate to vote for, paper or plastic, all present us with choices. Should the president deal with an international crisis through military inva-sion or diplomacy? How should the U.S. Congress act to address illegal immigration?

Is the defendant guilty as accused?The Daily Showor the ball game? And upon what information should I rely to make my decision?

Certainly some of these decisions are more consequential than others. Which amendment to vote for, what television program to watch, what course to take, which phone plan to purchase, and which diet to pursue all present unique chal-lenges. At our best, we seek out research and data to inform our decisions. Yet even the choice of which information to attend to requires decision making. In 2006, TIMEmagazine named YOU its “Person of the Year.” Congratulations! Its selection was based on the participation not of“great men”in the creation of his-tory, but rather on the contributions of a community of anonymous participants in the evolution of information. Through blogs, online networking, YouTube, Facebook, MySpace, Wikipedia, and many other“wikis,” knowledge and “truth” are created from the bottom up, bypassing the authoritarian control of newspeople, academics, and publishers. We have access to infinite quantities of information, but how do we sort through it and select the best information for our needs?

Miniglossary

Argumentation Reason giving in communicative situations by people whose purpose is the justification of acts, beliefs, attitudes, and values.

Coercion The threat or use of force.

Critical thinking The ability to analyze, criticize, and advocate ideas; to reason inductively and deductively; and to reach factual or judgmental conclusions based on sound inferences drawn from unambiguous statements of knowledge or belief.

Debate The process of inquiry and advocacy; the seeking of a reasoned judg-ment on a proposition.

Deontological ethics An ethical approach that is process- or act-oriented, and is based on the notion that actions have moral value.

Ethics A set of constructs that guide our decision making by providing stan-dards of behavior telling us how we ought to act.

Good reasons Reasons that are psychologically compelling for a given audi-ence, that make further inquiry both unnecessary and redundant—hence justi-fying a decision to affirm or reject a proposition.

Persuasion Communication intended to influence the acts, beliefs, attitudes, and values of others.

Propaganda The use of persuasion by a group (often a closely knit organiza-tion) in a sustained, organized campaign using multiple media for the purpose of influencing a mass audience.

Teleological ethics An ethical approach that is results oriented, and would fo-cus on the good or bad consequences of an action or a decision.

The ability of every decision maker to make good, reasoned, and ethical deci-sions relies heavily upon their ability to think critically. Critical thinking enables one to break argumentation down to its component parts in order to evaluate its relative validity and strength. Critical thinkers are better users of information, as well as bet-ter advocates.

Colleges and universities expect their students to develop theircritical think-ingskills and may require students to take designated courses to that end. The im-portance and value of such study is widely recognized.

The executive order establishing California’s requirement states:

Instruction incritical thinkingis designed to achieve an understanding of the relationship of language to logic, which would lead tothe ability to analyze, criticize, and advocate ideas, to reason inductively and deductively, and to reach factual or judgmental conclusions based on sound inferences drawn from unambiguous statements of knowledge or belief. The minimal competence to be expected at the successful conclusion of instruction in critical think-ing should be the ability to distthink-inguish fact from judgment, belief from knowledge, and skills in elementary inductive and deductive processes, including an understanding of the formal and informal fallacies of lan-guage and thought.

Competency in critical thinking is a prerequisite to participating effectively in human affairs, pursuing higher education, and succeeding in the highly competitive world of business and the professions. Michael Scriven and Richard Paul for the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking Instruction argued that the ef-fective critical thinker:

■ raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely; ■ gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it

effectively; comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

■ thinks open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing

and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical con-sequences; and

■ communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex

problems.

They also observed that critical thinking “entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism.”1 Debate as a classroom exercise and as a mode of thinking and be-having uniquely promotes development of each of these skill sets. Since classical times, debate has been one of the best methods of learning and applying the

1. Michael Scriven and Richard Paul,“Defining Critical Thinking,”The Critical Thinking Community, http://www.criticalthinking.org/aboutCT/definingCT.shtml.

principles of critical thinking. Contemporary research confirms the value of debate. One study concluded:

The impact of public communication training on the critical thinking ability of the participants is demonstrably positive. This summary of existing research reaffirms what many ex-debaters and others in foren-sics, public speaking, mock trial, or argumentation would support: par-ticipation improves the thinking of those involved.2

In particular, debate education improves the ability to think critically. In a comprehen-sive review of the relevant research, Kent Colbert concluded,“The debate–critical thinking literature provides presumptive proof favoring a positive debate–critical thinking relationship.”3

Much of the most significant communication of our lives is conducted in the form of debates. These may take place in intrapersonal communications, in which we weigh the pros and cons of an important decision in our own minds, or they may take place in interpersonal communications, in which we listen to arguments intended to influence our decision or participate in exchanges to influence the deci-sions of others.

Our success or failure in life is largely determined by our ability to make wise decisions for ourselves and to influence the decisions of others in ways that are ben-eficial to us. Much of our significant, purposeful activity is concerned with making decisions. Whether to join a campus organization, go to graduate school, accept a job offer, buy a car or house, move to another city, invest in a certain stock, or vote for Garcia—these are just a few of the thousands of decisions we may have to make. Often, intelligent self-interest or a sense of responsibility will require us to win the support of others. We may want a scholarship or a particular job for ourselves, a customer for our product, or a vote for our favored political candidate.

2. Mike Allen, Sandra Berkowitz, Steve Hunt, and Allan Louden,“A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Forensics and Communication Education on Critical Thinking,” Communication Education,vol. 48, no. 1 (Jan. 1999), p. 28.

3. Kent Colbert,“Enhancing Critical Thinking Ability Through Academic Debate,” Contemporary Argumentation and Debate: The Journal of the Cross Examination Debate Association,vol. 16 (1995), p. 69.

Critical Thinking

■ Life demands decision making

■ The ability to make reasoned decisions relies on critical thinking

■ Critical thinking enables analysis and evaluation of arguments

■ Critical thinking improves the use of information as well as advocacy

■ Teaching and learning critical thinking are important roles of education

Some people make decisions by flipping a coin. Others act on a whim or re-spond unconsciously to “hidden persuaders.” If the problem is trivial—such as whether to go to a concert or a film—the particular method used is unimportant. For more crucial matters, however, mature adults require a reasoned means of deci-sion making. Decideci-sions should be justified by good reasons based on accurate evi-dence and valid reasoning.

Argumentationis reason giving in communicative situations by people whose purpose is the justification of acts, beliefs, attitudes, and values—a definition based on language adopted at the National Developmental Conference on Forensics.4 British philosopher Stephen Toulmin makes a similar point when he asks,“What kind of justificatory activitiesmust we engage in to convince our fellows that these beliefs are based on ‘good reasons’?”5 Good reasons may be defined as “reasons which are psychologically compelling for a given audience, which make further inquiry both unnecessary and redundant—hence justifying a decision to affirm or reject a proposition.”6

Note that what constitutes good reasons for one audience may not be good rea-sons for another. When Taslina Nasrin wrote her novellaLajja (Shame), she became a target of Muslim fundamentalists. Their fury mounted when she was quoted—or misquoted, she insists—as saying that the Koran should be“revised thoroughly”to give equal rights to women. After all, Islam’s central article of faith is that the Koran is the literal word of God and is thus above revision. Nasrin’s challenge thus was seen as blasphemy and prompted legal charges and Muslim fatwas, or religious decrees, calling for her death:

A crowd of 100,000 demonstrators gathered outside the Parliament building in Dhaka to bay for her blood.…One particularly militant

faction threatened to loose thousands of poisonous snakes in the capital unless she was executed.7

4. James H. McBath, ed.,Forensics as Communication(Skokie, Ill.: National Textbook, 1975), p. 11.

5. Stephen Toulmin,Knowing and Acting(New York: Macmillan, 1976), p. 138. 6. David Zarefsky,“Criteria for Evaluating Non-Policy Argument,”inPerspectives on Non-Policy Argument,ed. Don Brownlee, sponsored by CEDA (privately published, 1980), p. 10. 7.Time,Aug. 15, 1994, p. 26.

Good Reasons

■ Argumentation relies on good reasons

■ Good reasons are audience-based justifications for or against propositions

■ Good reasons differ by audience and are therefore, impacted by culture

■ Argumentation guides decision making

This incident provides a dramatic example of cultural differences. To Muslim fundamentalists in Bangladesh, even being suspected of calling for a revision of the Koran is a“good reason”for execution.

In most of the world and for most Muslims, “blasphemy”is not perceived as a good reason for death. In America, freedom of the press, enshrined in the First Amendment to the Constitution, is perceived as a good reason for allowing an au-thor to express just about any opinion. A debater needs to discover the justificatory activities that the decision renderers will accept and to develop the good reasons that will lead them to agree with the desired conclusion—or, of course, to reject the rea-sons advanced by an opponent.

First we will consider debate as a method of critical thinking and reasoned deci-sion making. Then we will look at some other methods of decideci-sion making and see how they relate to argumentation and debate.

I . D E B A T E

Debate is the process of inquiry and advocacy, a way of arriving at a reasoned judgment on a proposition. Individuals may use debate to reach a decision in their own minds; alternatively, individuals or groups may use it to bring others around to their way of thinking.

Debate provides reasoned arguments for and against a proposition. It requires two competitive sides engaging in a bipolar clash of support for and against that proposition. Because it requires that listeners and opposing advocates compara-tively evaluate competing choices, debate demands critical thinking. Society, like individuals, must have an effective method of making decisions. A free society is structured in such a way that many of its decisions are arrived at through debate. For example, law courts and legislative bodies are designed to utilize debate as their means of reaching decisions. In fact, any organization that conducts its busi-ness according to parliamentary procedures has selected debate as its method. Debate pervades our society at decision-making levels.

The ancient Greeks were among the first to recognize the importance of debate for both the individual and society. Plato, whose dialogues were an early form of cross-examination debate, definedrhetoric as“a universal art of winning

the mind by arguments, which means not merely arguments in the courts of justice, and all other sorts of public councils, but in private conference as well.”8

Aristotle listed four functions for rhetoric.9First, it prevents the triumph of fraud and injustice. Aristotle argued that truth and justice are by nature more powerful than their opposites, so when poor decisions are made, speakers with right on their side have only themselves to blame. Thus, it is not enough to know the right decision ourselves; we also must be able to argue for that decision before others.

8. Plato,Phaedrus,261. Translators Cooper and Jowett use slightly different terms in in-terpreting this passage. This statement draws from both translations.

9. See Aristotle,Rhetoric,I, 1.

Second, rhetoric is a method of instruction for the public. Aristotle pointed out that in some situations scientific arguments are useless; a speaker has to“

ed-ucate”the audience by framing arguments with the help of common knowledge

and commonly accepted opinions. Congressional debates on health care or tax policies are examples of this. The general public, and for that matter the majority of Congress, is unable to follow highly sophisticated technical arguments. Skilled partisans who have the expertise to understand the technical data must reformu-late their reasons in ways that both Congress and the public can grasp.

Third, rhetoric makes us see both sides of a case. By arguing both sides, we become aware of all aspects of the case, and we will be prepared to refute our opponents’arguments.

Fourth, rhetoric is a means of defense. Often knowledge of argumentation and debate will be necessary to protect ourselves and our interests. As Aristotle stated:“If it is a disgrace to a man when he cannot defend himself in a bodily

way, it would be odd not to think him disgraced when he cannot defend himself with reason. Reason is more distinctive of man than is bodily effort.” Similarly,

in the nineteenth century, John Stuart Mill placed great emphasis on the value of debate:

If even the Newtonian philosophy were not permitted to be ques-tioned, mankind could not feel as complete assurance of its truth as they now [in 1858] do. The beliefs which we have the most warrant for, have no safeguard to rest on, but a standing invitation to the whole world to prove them unfounded. If the challenge is not ac-cepted, or is accepted and the attempt fails, we are far enough from certainty still; but we have done the best that the existing state of human reason admits of; we have neglected nothing that could give the truth the chance of reaching us; if the lists are kept open, we may hope that if there be a better truth, it will be found when the human mind is capable of receiving it; and in the meantime we may rely on having attained such approach to truth as is possible in our day. This is the amount of certainty attainable by a fallible being, and this is the sole way of attaining it.10

Half a century ago the United States Senate designated as Senate Immortals five senators who had shaped the history of the country by their ability as deba-ters: Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, Robert M. La Follette, Sr., and Robert A. Taft. The triumvirate of Webster, Clay, and Calhoun especially towered over all the others and were the near-unanimous choices of senators and scholars alike. As John F. Kennedy, then a freshman senator, pointed out, “For

over thirty years they dominated the Congress and the country, providing lead-ership and articulation on all the great issues of the growing nation.”11For their

part La Follette and Taft were selected as the outstanding representatives of,

10. John Stuart Mill,On Liberty(New York: Burt, n.d.), pp. 38–39. 11. John F. Kennedy, Senate speech, May 1, 1957, from a press release.

respectively, the progressive and the conservative movements in the twentieth century. In honoring these“immortals,” the Senate recognized the importance

of debate in determining the course of American history.

Our laws not only are made through the process of debate but are applied through debate as well. Today’s trial attorneys cite the famous dictum of attorney

Joseph N. Welch as a guide for contemporary legal practices:

America believes in what lawyers call“the adversary system” in our

courtrooms, including our criminal courts. It is our tradition that the District Attorney prosecutes hard. Against him is the lawyer hired by the defendant, or supplied by the court if the defendant is indigent. And the defendant’s lawyer defends hard. We believe that truth is apt to emerge

from this crucible. It usually does.12

We need debate not only in the legislature and the courtroom but in every other area of society as well. Most of our rights are directly or indirectly depen-dent on debate. As the influential journalist Walter Lippmann pointed out, one of our most cherished rights—freedom of speech—can be maintained only by

creating and encouraging debate:

Yet when genuine debate is lacking, freedom of speech does not work as it is meant to work. It has lost the principle which regulates and jus-tifies it—that is to say, dialectic conducted according to logic and the

rules of evidence. If there is no effective debate, the unrestricted right to speak will unloose so many propagandists, procurers, and panderers upon the public that sooner or later in self-defense the people will turn to the censors to protect them. It will be curtailed for all manner of reasons and pretexts, and serve all kinds of good, foolish, or sinister ends.

For in the absence of debate unrestricted utterance leads to the degradation of opinion. By a kind of Gresham’s law the more rational is

overcome by the less rational, and the opinions that will prevail will be those which are held most ardently by those with the most passionate will. For that reason the freedom to speak can never be maintained by objecting to interference with the liberty of the press, of printing, of broadcasting, of the screen. It can be maintained only by promoting debate.13

We need debate both to maintain freedom of speech and to provide a meth-odology for investigation of and judgment about contemporary problems. As Chaim Perelman, the Belgian philosopher-rhetorician whose works in rhetoric and argumentation are influential in argumentation and debate, pointed out:

12. Joseph N. Welch,“Should a Lawyer Defend a Guilty Man?”This Weekmagazine, Dec. 6, 1959, p. 11. Copyright 1959 by the United Newspapers Magazine Corporation. 13. Walter Lippmann,Essays in the Public Philosophy(Boston: Little, Brown, 1955), pp. 129–130.

If we assume it to be possible without recourse to violence to reach agreement on all the problems implied in the employment of the idea of justice we are granting the possibility of formulating an ideal of man and society, valid for all beings endowed with reason and accepted by what we have called elsewhere the universal audience.14

I think that the only discursive methods available to us stem from techniques that are not demonstrative—that is, conclusive andrationalin

the narrow sense of the term—but from argumentative techniques

which are not conclusive but which may tend to demonstrate the rea-sonablecharacter of the conceptions put forward. It is this recourse to the rational and reasonable for the realization of the ideal of universal com-munion that characterizes the age-long endeavor of all philosophies in their aspiration for a city of man in which violence may progressively give way to wisdom.15

Here we have touched on the long-standing concern of philosophers and po-litical leaders with debate as an instrument for dealing with society’s problems. We

can now understand why debate is pervasive. Individuals benefit from knowing the principles of argumentation and debate and from being able to apply these princi-ples in making decisions and influencing the decisions of others. Society benefits if debate is encouraged, because free and open debate protects the rights of indivi-duals and offers the larger society a way of reaching optimal decisions.

I I . I N D I V I D U A L D E C I S I O N S

Whenever an individual controls the dimensions of a problem, he or she can solve the problem through a personal decision. For example, if the problem is whether to go to the basketball game tonight, if tickets are not too expensive and if transportation is available, the decision can be made individually. But if a friend’s car is needed to get to the game, then that person’s decision to furnish

the transportation must be obtained.

Complex problems, too, are subject to individual decision making. American business offers many examples of small companies that grew into major corporations while still under the individual control of the founder. Some com-puter companies that began in the 1970s as one-person operations burgeoned into multimillion-dollar corporations with the original inventor still making all the major decisions. And some of the multibillion-dollar leveraged buyouts of the 1980s were put together by daring—some would say greedy—financiers

who made the day-to-day and even hour-to-hour decisions individually.

14. Chaim Perelman and L. Olbrechts-Tyteca,Traite de l’argumentation, La nouvelle rhetori-que(Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1958), sec. 7.

15. Chaim Perelman,The Idea of Justice and the Problem of Argument,trans. John Petrie (New York: Humanities Press, 1963), pp. 86–87.

When President George H. W. Bush launched Operation Desert Storm, when President Bill Clinton sent troops into Somalia and Haiti and authorized Operation Desert Fox, and when President George W. Bush authorized Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq, they each used different methods of decision making, but in each case the ultimate decision was an individual one. In fact, many government decisions can be made only by the president. As Walter Lippmann pointed out, debate is the only satisfactory way the great issues can be decided:

A president, whoever he is, has to find a way of understanding the novel and changing issues which he must, under the Constitution, decide. Broadly speaking…the president has two ways of making up his mind.

The one is to turn to his subordinates—to his chiefs of staff and his

cabinet officers and undersecretaries and the like—and to direct them to

argue out the issues and to bring him an agreed decision.…

The other way is to sit like a judge at a hearing where the issues to be decided are debated. After he has heard the debate, after he has ex-amined the evidence, after he has heard the debaters cross-examine one another, after he has questioned them himself, he makes his decision.…

It is a much harder method in that it subjects the president to the stress of feeling the full impact of conflicting views, and then to the strain of making his decision, fully aware of how momentous it is. But there is no other satisfactory way by which momentous and complex issues can be decided.16

John F. Kennedy used Cabinet sessions and National Security Council meet-ings to provide debate to illuminate diverse points of view, expose errors, and challenge assumptions before he reached decisions.17 As he gained experience in office, he placed greater emphasis on debate. One historian points out:“One

reason for the difference between the Bay of Pigs and the missile crisis was that [the Bay of Pigs] fiasco instructed Kennedy in the importance of uninhibited de-bate in advance of major decision.”18All presidents, to varying degrees,

encour-age debate among their advisors.

We may never be called on to render the final decision on great issues of national policy, but we are constantly concerned with decisions important to ourselves for which debate can be applied in similar ways. That is, this debate may take place in our minds as we weigh the pros and cons of the problem, or we may arrange for others to debate the problem for us. Because we all are in-creasingly involved in the decisions of the campus, community, and society in

16. Walter Lippmann,“How to Make Decisions,”New York Herald Tribune, Mar. 3, 1960. 17. See Theodore C. Sorensen,Decision-Making in the White House(New York: Columbia University Press, 1963), p. 59.

18. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.,Imperial Presidency(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973), p. 215.

general, it is in our intelligent self-interest to reach these decisions through rea-soned debate.

When we make an individual decision, we can put it into effect if we con-trol the necessary conditions. If we need the consent or cooperation of others to carry out our decision, we have to find a way of obtaining the appropriate re-sponse from them by debate—or by group discussion, persuasion, propaganda,

coercion, or a combination of methods.

I I I . G R O U P D I S C U S S I O N

Decisions may be reached by group discussion when the members of the group (1) agree that a problem exists, (2) have compatible standards or values, (3) have compatible purposes, (4) are willing to accept the consensus of the group, and (5) are relatively few in number. When these conditions are met and when all rele-vant evidence and arguments are carefully weighed, group discussion is a rea-soned means of decision making.

In February 1999, after the bitter and divisive House impeachment proceed-ings and subsequent Senate trial, President Bill Clinton was acquitted on two articles of impeachment. The vote on impeachment in the House occurred on straight party lines. Although there were some Republican defectors in the Senate vote, partisan tensions were heightened by the trial, as were tensions be-tween the legislative and executive branches of the government. Despite the clash of personalities and the difficulties inherent in such partisan and interbranch differences, House and Senate leaders and President Clinton pledged to work together for the good of the country. Indeed a strength of American politics is that skilled leaders in both parties traditionally have been able to override politi-cal differences and enact at least some important legislation on which both parties could agree.

When a group has more than 15 or 20 members, productive discussion be-comes difficult if not impossible. A group of senators can discuss a problem in committee, but not on the floor of the Senate. The Senate is too large for dis-cussion; there debate must be used. Of course, informal debate may take place

Standard Agenda for Group Decision Making

■ Define and analyze the problem

■ Research the problem

■ Establish criteria

■ Generate solutions

■ Select best solution

■ Implement and monitor solution

within the discussion process, and discussion may be a precursor of debate.19If the differences cannot be solved by discussion, debate is the logical alternative. Or if the group, such as a Senate subcommittee, reaches a decision by discussion, it may be necessary to debate it on the floor to carry the Senate as a whole.

Group decision making is best guided by a systematic procedure for problem solving. The first step requires that group members define and analyze the prob-lem they are to address. They should determine the nature of the probprob-lem and its impacts, distinguishing causes from symptoms and measuring the relative impor-tance of each. An important outcome of this step is an agreed upon statement of the problem. Second, they should research the problem, gathering and evaluat-ing available information relevant to the problem as defined. The third step is perhaps the most important, and most often overlooked: establishing and priori-tizing the criteria that will distinguish a successful solution. These criteria may be given numerical value. Fourth, the group members should generate a list of pos-sible solutions through a process of brainstorming; and fifth, they should apply the criteria to the established list to select the best solution. Finally, the sixth step is to implement and monitor the solution, leading to reevaluation and in many situations, a return to step one.

Like an individual, a group may act on its decision only insofar as it has the power to do so. If it needs the consent or cooperation of others to carry out a particular plan, the group must use other means to secure their cooperation.

I V . P E R S U A S I O N

Purposefulpersuasion is defined ascommunication intended to influence the acts, be-liefs, attitudes, and values of others. Clearly, one method of persuasion is debate. Persuasion is not, however, limited to seeking carefully reasoned judgments, as is debate, nor does persuasion require logical arguments both for and against a given proposition. The “Marlboro Man” advertising campaign, for example,

must have been judged as highly effective persuasion by the company that ran it for many years, but it did not seek the kind of carefully thought-out judgment that one associates with debate.

Frequently the persuader hopes to dominate the stage and avoid situations in which another side of the argument might be presented. Consider the cigarette companies, which accepted the ban on TV advertising without the prolonged court battle that many expected. The reason for this may have been that the TV stations were required to give equal time to public service announcements about the hazards of smoking. The tobacco companies apparently found it pref-erable to direct their advertising dollars to media that did not have an equal-time requirement. President Hugo Chavez of Venezuela recently made international headlines and prompted national protests when he failed to renew the license of

19. See James H. McBurney, James M. O’Neill, and Glen E. Mills,Argumentation and Debate(New York: Macmillan, 1951), p. 67.

Radio Caracas Television (RCTV), a popular television network, likely because it had been critical of him, thus effectively eliminating local opposition to his government.20

Persuaders select the type of persuasive appeals they believe to be best adapted to their audience. These may include such diverse communications as a picket line, a silent prayer vigil, a clever negative political commercial on TV, or the stately formality of a debate before the Supreme Court. (Audience analysis is considered in Chapter 15.)

Persuaders reach a decision on the problem before they begin the process of persuasion. They continue the process of persuasion until they solve the problem by persuading others to accept their decision or until they are convinced that further efforts are pointless. In trying to influence others, they may find it neces-sary or advantageous (1) to join with other persuaders and become propagandists or (2) to face the opposition and become debaters. Thus they must be familiar with the principles of argumentation and debate. This knowledge is also a de-fense against the persuasion of others. If we subject their appeals to critical anal-ysis, we increase our likelihood of making reasoned decisions. And if persuaders advocate a decision we believe to be unsound, we may find it necessary to be-come debaters and advocate the conclusion we favor.

Unintended persuasion occurs when we receive a message not intended for us—for example, we overhear a private conversation in an elevator and are

influ-enced by it—or when we unknowingly communicate to and influence others in

an unintended way.

V . P R O P A G A N D A

Propagandais the use of persuasion by a group (often a closely knit organiza-tion) in a sustained, organized campaign using multiple media for the purpose of influencing a mass audience. Historically propaganda has been associated with religious, social, or political movements. Today the term has been expanded to include commercial advertising campaigns. The term first came into common use in 1622 when Pope Gregory XV established the Sacred Congregation for Propagating the Faith. What, in the view of the faithful, could be more com-mendable than spreading the faith? In 1933, when Hitler appointed Dr. Joseph Goebbels as his minister of propaganda, the word took on a different connota-tion. From the standpoint of non-Nazis, what could be more evil than spreading Nazism? Even todaypropaganda often is perceived as a pejorative term. Imagine an official of a women’s group saying:

We’ve been conducting an extensive educational campaign to inform

the public of the necessity of making abortion on demand available to

20. Christopher Toothaker,“Chavez Warns Foreign Critics,”The Miami Herald,July 23, 2007, p. 8A.

women on welfare. It was going very well until the churches unleashed a bunch of propagandists to work against us.

Thus, in everyday language,we educate or give information, while they propa-gandize. Another example is President Chavez of Venezuela. He spoke to the United Nations in 2007, referring to President George Bush as “the devil.”

Later Chavez threatened to deport international visitors from Venezuela who were critical of him and his government.

Of course, the end does not justify the means. Propaganda, like persuasion, may be viewed as good or bad only to the degree that it is based on true evi-dence and valid reasoning. Examples of questionable methods may be found in the Allied propaganda in the United States prior to America’s entry into World

War I. At that time extensive use was made of distorted or false atrocity stories. Other examples may be found in communist propaganda from the former Soviet Union, which made extensive use of the technique of the “big lie.” During

Middle East crises both Israel and the Arab countries have conducted propaganda campaigns in the United States designed to sway public opinion in their favor. Each side obviously thinks of theirs as good and the other’s as bad.

Examples of propaganda used for good purposes include the various cam-paigns designed to get the public to drive safely, to recognize the symptoms of cancer, and to practice safe sex; these examples are usually based on sound evi-dence and reasonable inference. Other examples include campaigns by churches to persuade people to act in accordance with the Ten Commandments and by charitable groups to raise funds for the homeless or for people with AIDS. Propagandists reach a decision on a problem before they begin the process of propaganda. They continue their campaign until they solve the problem by per-suading others to accept their decision or are convinced that further efforts are pointless. In their efforts to influence others, propagandists may find it necessary or advantageous to confront their opponents and become debaters. In such cases they need knowledge of argumentation and debate. If their evidence is accurate, their reasoning valid, and their appeals chosen carefully, the campaign will have the greatest opportunity for success. If any of the conditions is lacking, however, the chances for success are diminished.

Similarly, knowledge of argumentation and debate is an important defense against the propaganda campaigns we constantly confront. Unless we subject propaganda to critical analysis, we will be unable to distinguish the good from the bad. We will lose our ability to make reasonable decisions and may fall prey to“hidden persuaders.”

V I . C O E R C I O N

may not physically or mentally abuse their children; criminals may be sentenced to prison only after they have an opportunity to defend themselves in court; the United States may declare war only after the advocates of war win consent in Congress. President Bush found it prudent to obtain congressional approval for the use of force in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom. In a democratic society coercion as a method of solv-ing problems—by private individuals or the state—is generally prohibited except

in special cases in which it has been found necessary after debate. A totalitarian society, by contrast, is characterized by sharply limited debate and by almost om-nipresent coercion.21

Coercion may be employed to influence a decision. The coercive powers of the state represent a strong logical appeal against a decision to commit a crime, and for some individuals it may be the only effective appeal. In arguing in favor of policy propositions, affirmative debaters often provide for coercion in the plan of action they advocate. They may include an “enforcement plank” providing

for fines, imprisonment, or some other penalty for those who do not obey or who try to circumvent the requirements of the plan. Alternatively they may ad-vocate enforcement of the plan through existing legal structures.

A decision to employ coercion is likely to be socially acceptable and effec-tive when that decision is made after full and fair debate. Baron Karl von Clausewitz’s classic definition of war as the“continuation of diplomacy by other

means”suggests that war—the ultimate form of coercion—is a method of

prob-lem solving to be selected after a careful debate on the possible risks and benefits.

V I I . C O M B I N A T I O N O F M E T H O D S

It is often necessary to use a combination of methods in making a decision. The social context will determine the most suitable methods in a particular case.

The solution to a problem requiring the consent or cooperation of others may extend over a considerable period of time and may warrant use of all the

Methods of Decision Making

■ Debate

■ Individual Decision

■ Group Decision

■ Propaganda

■ Coercion

■ Combination of Methods

21. See Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn,The Gulag Archipelago(New York: Harper & Row, 1974).

methods of decision making. For example, through individual decision a person might determine that nonrefundable beverage containers cause unacceptable lit-ter and should be prohibited.

Because that person is powerless to implement such a decision alone, he or she must usepersuasion to influence friends to join in the effort. They may use the process ofgroup discussion to decide how to proceed toward their objective. They might find it necessary to organize a group for raising funds and to work together for a period of months or years conducting a propaganda campaign di-rected toward the voters of the state. During this campaign many individuals might play a role inpersuadingordebating. Eventually a bill might be introduced into the state legislature.

Afterdiscussionin committee hearings and a number ofdebateson the floor of the legislature, a final debate determines the disposition of the bill. If the bill is enacted into law, coercion will be provided to ensure compliance. The validity of the law probably will be tested bydebatesin the courts to determine its consti-tutionality. When the law is violated,coercioncan be applied only as the result of

debatesin the courts.

V I I I . E T H I C A L D E C I S I O N M A K I N G

In addition to making well-reasoned decisions, it is important to make decisions that areethical. The consequences of a failure to consider ethical constructs when making decisions range from business failures (ENRON) to incarceration (Scooter Libbey), to the destruction of personal relationships. Ethics are a set of constructs that guide our decision making by providing standards of behavior telling us how we ought to act. While ethics may be based on or reflected in laws, they are not the same as laws. Similarly, we learn value systems and thus standards for ethical behavior from our communities and cultures, but that a be-havior is a cultural standard or norm does not make it ethical.

According to Thomas White, there are two broad philosophical approaches to understanding ethical choices: teleological and deontological. The teleo-logical approach is results oriented, and would focus on the good or bad conse-quences of an action or a decision. The deontological ethic is process or act ori-ented, and is based on the notion that actions have moral value.22Scholars at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University have suggested that in making ethical decisions one ought to follow a framework through the following steps:

■ Recognize an ethical issue ■ Get the facts

22. Thomas White,“Philosophical Ethics,” http://www.ethicsandbusiness.org/pdf/strat-egy.pdf. Adapted from Thomas White,“Ethics,”inBusiness Ethics: A Philosophical Reader (New York: Macmillan, 1993).

■ Evaluate alternative actions from various ethical perspectives ■ Make a decision and test it

■ Act, then reflect on the decision later23

Debate offers the ideal tool for examining the ethical implications of any decision, and critical thinking should also be ethical thinking.

How do we reach a decision on any matters of importance? We are under constant pressure to make unreasoned decisions, and we often make decisions carelessly. But which method is most likely to lead to wise decisions? To make wise judgments, we should rely on critical thinking. In many situations argumen-tation’s emphasis on reasoned considerations and debate’s confrontation of

op-posing sides give us our best, and perhaps only, opportunity to reach reasoned conclusions. In any case it is in the public interest to promote debate, and it is in our own intelligent self-interest to know the principles of argumentation and to be able to apply critical thinking in debate.

E X E R C I S E S

1. Individual decisions. For one week, keep a journal of decisions you make. Separate them into trivial, somewhat important and very important deci-sions. How did you make your decisions? Upon what did you base your decisions? Can you identify a pattern based on level of importance? 2. SPAR debates(SPontaneous ARgumentation). This is a classic introductory

debate exercise.

Format

Affirmative (Pro side) opening speech Cross-Examination by Negative (Con side) Negative opening speech

Cross-Examination by Affirmative Affirmative closing speech

Negative closing speech

90 seconds 60 seconds 90 seconds 60 seconds 45 seconds 45 seconds

Procedure

Debaters step to the front of the room in pairs. One debater calls a coin flip. The winner may either choose the topic (from a list posted on the board) or the side they will defend. After two minutes of preparation time the debate begins. Each debater has a total one minute additional prepa-ration time to be used during the debate. There should always be an on-deck pair of debaters preparing their arguments.

E X E R C I S E S 1 7

Possible topics

Honesty is always the best policy. Slavery still exists today.

True love really does exist.

Violence is a necessary means to settle disputes. Police are necessary for safety.

People should not eat meat.

The drinking age should be lowered to 18. Smoking should be banned in all public places. There is no such thing as Homeland Security. Marijuana should be legalized.

3. Group discussion. Students should form groups of five to seven and using the standard agenda for group problem solving, complete the following exercise. As the most outstanding and well-respected students in your Ethics in Communication course, your professor has asked you to formulate a recom-mendation to her concerning a problem in the class.

It has come to the attention of Professor Young that one of the students in the class plagiarized on an assigned paper. Sue M. Moral turned in a pa-per, more than half of which was actually written by her good friend Ben There. Ben had written the original paper for the same course two years ago, and suggested to Sue that she use his paper for her assignment. Since Professor Old had taught the course (since retired) when Ben took the course, Professor Young would be unlikely to recognize the work. Ben did not know that Professor Old had been so impressed with his paper that he had given it to Professor Young as a sample paper for her to keep on file. Professor Young also found out that Sue’s roommate, Bye Stander,

also a student in Ethics in Communication, knew about Sue’s plagiarism,

but did not inform Professor Young. In fact, Bye had agreed to photocopy Ben’s paper for Sue, since she was making a trip to Kinko’s for other

rea-sons. The assignment counts 10 percent of the course grade. Sue has a “B”

average on all other work in the class. Bye has an “A”average. Ben is still a

major in the department. His“A” on the paper barely enabled him an“A”

in Ethics in Communication. He hopes to graduate next semester with a

“C” average.

What, if any, action do you recommend Professor Young take? 4. Persuasion. Prepare a two-minute impromptu speech in support of your claim

that“People should do ”or“People should NOT do .”

Offer three reasons in support of your claim.

5. Ethics. Identify an ethical dilemma for decision making. Follow the frame-work suggested in the chapter to make a decision resolving the dilemma. Identify your ethical approach as teleological or deontological. An excellent source of hypothetical case studies is available at http://www.uvsc.edu/ ethics/casestudies/

2

Applied and Academic Debate

O

n his first day of class in argumentation and debate, his professor asked Charles why he had chosen the course. Charles responded that“I always argue with myparents and friends. In fact, I often call my favorite radio sports-talk show to argue with the host. My mother is an attorney, and she sometimes practices her openings and summations for me. And I practically live online, defending myself on the Listserv I belong to and networking with my friends on the net. So I know all about argumentation and debate, and I’m good at it!”Charles correctly recognized that the

principles of debate are important across many different fields of practical arguing. But he was not yet aware of the richness and diversity of debate practice.

Debate can be classified into two broad categories: applied and educational.

Applied debate is conducted on propositions, questions, and topics in which the advocates have a special interest, and the debate is presented before a judge or an audience with the power to render a binding decision on the proposition or respond to the question or topic in a real way.Academic debateis conducted on proposi-tions in which the advocates have an academic interest, and the debate typically is presented before a teacher, judge or audience without direct power to render a de-cision on the proposition. Of course the audience in an academic debate does form opinions about the subject matter of the debate, and that personal transformation may ultimately lead to meaningful action. However, the direct impact of the audi-ence decision in an academic debate is personal, and the decision made by the judge is limited to identification of the winner of the debate. In fact, in academic debate the judge may be advised to disregard the merits of the proposition and to render her win/loss decision only on the merits of the support as presented in the debate itself. The most important identifying characteristic of an academic debate is that the pur-pose of the debate is to provide educational opportunities for the participants.

I . A P P L I E D D E B A T E

Applied debate may be classified as special debate, judicial debate, parliamentary debate, or nonformal debate. After discussing each of these classifications of de-bate briefly, we will consider academic dede-bate in more detail.

A. Special Debate

Special debate is conducted under special rules drafted for a specific occasion, such as political campaign debates. Examples include the Lincoln–Douglas

de-bates of 1858, the Kennedy–Nixon debates of 1960, the Bush–Clinton–Perot Miniglossary

Academic debate Debate conducted under the direction of an educational in-stitution for the purpose of providing educational opportunities for its students.

Applied debate Debate presented before a judge or audience with the power to render a binding decision on the proposition.

CEDA Cross Examination Debate Association.

Ethical Being in accordance with the accepted principles of right and wrong that govern the conduct of a profession or community.

Forensics An educational activity primarily concerned with using an argumen-tative perspective in examining problems and communicating with people.

Judicial debate Debate conducted in the courts or before quasi-judicial bodies.

Mock trial debate A form of academic debate that emulates trial court debating.

Moot court debate An academic form of judicial debate used by law schools to prepare students for courtroom debate.

NDT National Debate Tournament.

Nonformal debate Debate that occurs in various contexts without formal or prearranged procedural rules.

Parliamentary debate Debate conducted under the rules of parliamentary pro-cedure (see Chapter 19). Also a form of competitive academic debate practiced under the auspices of organizations like the National Parliamentary Debate Association and the American Parliamentary Debate Association.

Special debate Debate conducted under special rules drafted for a specific oc-casion—for example, presidential debates.

debates of 1992, the Bush–Gore debates of 2000, Bush–Kerry in 2004, and the

series of debates involving the candidates for the Democratic and Republican Partys’ nominations during the 2007–2008 campaigns. These were formal

de-bates, yet they were neither judicial nor parliamentary; they were conducted un-der special rules agreed on by the debaters. In an article published in theSeattle Times, Paul Farhi and Mike Allen described the process that led to the special rules for the Bush–Kerry debates in 2004:

After weeks of private and reportedly heated negotiations, representa-tives of President Bush and Sen. John Kerry agreed earlier this week to three televised debates, with another for Vice President Cheney and Sen. John Edwards. The first presidential debate takes place Thursday at the University of Miami.

And now, with the release of a 32-page‘memorandum of

under-standing,’we understand why it took so long. The document is

crammed with sections and subsections spelling out almost every imag-inable rule of engagement and detail about how the debates will look. Or will be prohibited from looking.

In its precision and seeming fussiness, in its attempt at control, it often reads like an agreement between a concert promoter and a par-ticularly demanding pop diva.…

While the most important part of such agreements certainly has to do with the details governing the format and nature of questions or topics addressed, all details are considered. The authors continued,

The agreement, for example, spells out the exact dimensions of the lectern to be used (50 inches high on the side facing the audience, 48 inches on the side facing the candidates) in the first and third debates, and how far apart those lecterns will be (10 feet, as measured from‘the

left-right center’ of one ‘to the left-right center of the other’). It

spe-cifies the type of stools (identical, of equal height, with backs and footrests) that Bush and Kerry will sit on for the second, town-hall-style debate, as well as the arrangement (in a horseshoe) and nature of the audience. It specifies that it will consist of an equal number of ‘likely

voters who are“soft” Bush supporters or “soft” Kerry supporters,’soft

being a polling term for people who might be willing to change their minds. There are details about the type of warning lights to be used if a candidate runs over his allotted time, about the moderators’ conduct,

about the coin flip that will be used to determine who goes first (the type of coin or number of flips isn’t specified). There’s even a codicil

that might be called‘the perspiration clause,’ since it alludes to every

candidate’s worst fear: an outbreak of Nixon-style flop sweat. The

clause commits the nonpartisan producer, the Commission on Presidential Debates, to use its ‘best efforts to maintain an appropriate

temperature according to industry standards for the entire debate,’

although it’s unclear what ‘industry standard’temperature is, or even

what industry the agreement is referring to.1

Debates between presidential candidates are now well established in the American political scene, and similar debates are often held between candidates in elections at all levels, from student government president to mayor to vice president. While the formats of these debates may leave much to be desired, they at least bring the candidates together and give voters a better opportunity to compare the candidates than they would otherwise have. Although this type of debate is most often associated with political figures and campaign issues, it may be used by anyone on any proposition or set of questions or topics. Opposing advocates merely have to agree to come together under the provisions of a special set of rules drafted for the occasion.

B. Judicial Debate

Judicial debate is conducted in the courts or before quasi-judicial bodies. Governed by the rules of a court of law, its purpose is the prosecution or defense of individuals charged with violation of the law or the determination of issues of law alleged to be applicable to specific cases before the court. Court TV and other television and even Internet access makes courtroom argument easily ac-cessible to interested spectators.

Judicial debate may be observed in any court from the Supreme Court of the United States to a local court. In its academic form, judicial debate is known asmoot court debateand is used by law schools to prepare students for court-room debate. The impeachment trial of President Clinton during the winter of 1999 is a rare example of judicial debate held before the United States Congress under special rules establishing the Senate as a jury and presided over by the chief justice of the Supreme Court.

The principles of argumentation and debate apply to judicial debate. Because judicial debate is also concerned with sometimes highly technical rules of proce-dure—which may vary from federal to state courts, from one state to another,

and from one type of court to another within a given state—the specific

meth-ods of judicial debate are not considered here.Mock trial debate, which emu-lates the form of trial court debating but without the emphasis on rules of pro-cedure and admissibility, is considered in Chapter 18. Of course, moot court and mock trial debates are academic and not applied, as their judges do not render binding decisions on formal cases.

C. Parliamentary Debate

Parliamentary debateis conducted under the rules of parliamentary procedure. Its purpose is the passage, amendment, or defeat of motions and resolutions that

1. Paul Farhi and Mike Allen,“Rules of Engagement: Presidential Debate Details”The Seattle Times,Sept. 28, 2004; page updated 02:22P.M., http://seattletimes.nwsource .com/html/politics/2002048299_webdebaterules28.html.