Tobacco and Public

Health: Science and

Policy

Edited by

Peter Boyle

DirectorDivision of Epidemiology and Biostatistics European Institute of Oncology

Milan, Italy

Nigel Gray

Senior Research Associate

Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics European Institute of Oncology

Milan, Italy

Jack Henningfield

Associate Professor of Behavioural Biology Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Bethesda, Maryland, USA

John Seffrin

Chief Executive Officer American Cancer Society Atlanta, USAWitold Zatonski

DirectorDivision of Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention The Marie-Sklodowska Memorial Cancer Center and

Institute of Oncology Warsaw, Poland

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press, 2004

The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data ISBN 0 19 852687 3

Typeset by Cepha Imaging Pvt Ltd., Bangalore, India Printed in Great Britain

Preface

Tobacco: The public health disaster

of the twentieth century

At the dawn of the twentieth century, public health interventions and medical break-throughs were beginning to radically curb many forms of disease and premature death (CDC 1999a). It was also a time in which lung cancer was so rare that surgeons traveled to witness and learn from the few operations performed to save the lives of those afflicted (Kluger 1996; Wynder 1997). It was also a time in which an outgrowth of the cottage tobacco industry was metastasizing into one of the largest companies in the United States (Corti 1931; Taylor 1984; White 1988). That company was the American Tobacco Company, and it came to rival US Steel and Standard Oil as an economic and political powerhouse in the first few two decades of the twentieth century (Taylor 1984; White 1988). In the decades to follow, it would come to be rivaled by no industry and no war in terms of destruction of human life. By the end of the twentieth century, the offspring of this company, which I will collectively refer to as ‘Big Tobacco’, were selling enough cigarettes to kill more than 400 000 people annually in the United States and 5 million, worldwide (Garrett et al.2002). On current course, the global trajectory will increase to 10 million deaths per year early in the twenty-first century and will cost the lives of nearly one-half of the world’s 1.1 billion cigarette smokers (World Bank 1999).

The enormity of that number is almost incomprehensible, but in terms of lives lost to tobacco, it is equal to the Titanic sinking every 27 min for 25 years, or the Vietnam War death toll every day for 25 years.

These statistics can become numbing by their almost inconceivable magnitude. So it becomes important to frame the challenge, and our focus, constructively. When I became the United States’ spokesperson for AIDS in the early years of the epidemic, I said we were fighting a disease, not the people who had it. For tobacco use, however, I have to say that we are fighting the diseases produced by tobacco as well as the purveyors of tobacco products, who have knowingly spread disease, disability, and death throughout the world. We should not ostracize those who have been harmed the most, namely tobacco-addicted persons, but rather should work with them to reduce their risk of disease and to prevent the further spread of this deadly affliction. Ostracism should be reserved for those whose greed and duplicity have made Big Tobacco our most loathsome industry.

from legal recourse, and possesses enormous political influence and economic power that it is willing to use to undermine public health efforts (Orey 1999; Kessler 2000). In addition, it sells a highly addictive product that, ironically, makes many of its most debilitated consumers its strongest supporters (Taylor 1984; Kluger 1996; Givel and Glantz 2001). By way of contrast, there are probably few malaria-afflicted persons who would fight for their ‘right’ to continue to be exposed to the mosquitoes spreading this disease, nor are HIV-afflicted persons lobbying for the right of other persons to willfully afflict others with the disease, but there is a ‘smokers rights’ movement, which must be appropriately addressed and hopefully recruited to the side of public health.

The enormity and complexity of the public health assault demands a broad and sophisticated public health response. I would like to take this opportunity to comment briefly on what I believe should be our vision for health, and how we can achieve it. I will begin with a few additional comments on how we got to this place in the epidemic, because an understanding of these issues is crucial in addressing the problem.

Historical perspective

Tobacco use and addiction have existed for centuries, and there surely was resultant death and disease (Corti 1931; US DHHS 1989). However, tobacco-based mass destruc-tion of life on a global scale was only possible with the emergence of multinadestruc-tional companies capable of the daily production and distribution of billions of units of the most destructive of all forms of tobacco—the cigarette. Further, the modern cigarette has extraordinarily toxic and addictive capability: its increasingly smooth and alkaline smoke both enable, and require, inhalation of the toxins deep into the lungs to maxi-mize nicotine absorption. James Albert Bonsack, who invented the modern cigarette machine, also deserves some discredit; however, if he hadn’t invented it, someone else would have done so soon enough.

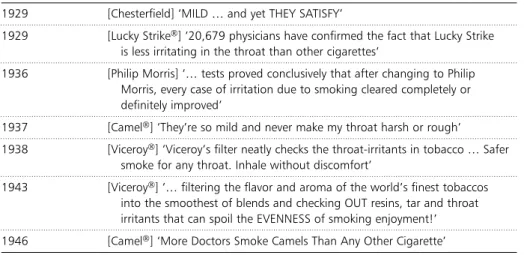

The cigarette companies hid much of their knowledge of the addiction issue and, until recently, disputed the possibility that cigarette smoking was addictive (Kessler 2000). The industry addressed the lung cancer issue head on in the press, with their Frank statement to cigarette smokers, published in major newspapers in 1954. In this state-ment, Big Tobacco disputed the link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer, accepted an interest in people’s health as a basic responsibility, and pledged to cooperate closely with public-health experts, among other promises broken long ago. Such strate-gies enabled Big Tobacco to buy time, buy influence over politicians, buy exemptions for their products from consumer product laws intended to minimize unnecessary harm from other products, and even to buy questionable science in an effort to under-mine, or at least complicate, interpretation of the science that damned their products (Taylor 1984; White 1988; Kluger 1996; Hirschhorn 2000; Hirschhorn et al.2000).

In the 1960s the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) tried to provide consumers with a means of selecting presumably less toxic products and to provide cigarette com-panies with an incentive to make such products. The Commission adopted a cigarette testing method originally developed by the American Tobacco Company (Bradford et al.1936) and later recognized as the FTC method for measuring tar and nicotine levels (National Cancer Institute 1996, 2001). Big Tobacco responded by developing creative methods to circumvent the test, in order to enable consumers to continue to expose themselves readily to high levels of tar and nicotine with ‘elastic’ cigarette designs, and then to thwart efforts to revise constructively the testing methods for greater accuracy (National Cancer Institute 1996, 2001; Wilkenfeld et al.2000). The FTC method was codified internationally as the International Standards Organization (ISO) method and Big Tobacco globally extended its deadly game of con-sumer deception and obfuscation of efforts to provide meaningful information about the nicotine and toxin deliveries of its products (Bialous and Yach 2001; World Health Organization 2001).

It was not until the 1990s that the American Cancer Society (Thun and Burns 2001) and National Cancer Institute (1996) recognized that the advertised benefits of so-called ‘reduced tar’ or ‘light’ cigarettes were virtually nonexistent, and that the mar-keting of these products may have actually impaired public health by undermining tobacco use prevention and cessation efforts (Stratton et al.2000; Wilkenfeld et al. 2000; National Cancer Institute 2001). Many smokers, realizing the scientifically proven health risk to smoking cigarettes, switched to ‘reduced tar’ or ‘lighter’ cigarettes, believing they were doing the reasonable thing to reduce risk and improve their health. We can never let history repeat itself. As Big Tobacco, and small tobacco companies, attempt to entice us with the false promises of their new generations of so-called ‘reduced risk’ products (Fairclough 2000; Slade 2000), we must be at least as skeptical of them as we would be of pharmaceutical and food products sold on the basis of their health claims (explicit or implied).Scientific proof to the satisfaction of an empowered agency, such as the Food and Drug Administration,must be the gold standard for

‘reduced risk’ or other health claims made by the tobacco industry. This standard should apply to claims including those implied through the use of terms such as ‘light’ or ‘low tar’. Meeting the standard should be required priorto the marketing of any new brand of cigarettes and any new type of tobacco product making such claims.

My vision for tobacco and health in the twenty-first century

My vision for the future is simple and achievable: To improve global health by drastically reducing the risk of disease and premature death in existing tobacco users and by sever-ing the pipeline of tomorrow’s tobacco users. I turn your attention to Fig. 1, developed by the World Bank (1999), projecting mortality from the middle of the twentieth cen-tury to 2050 (see above, p. 00). This figure illustrates the grim current course. What gives us hope for the future is the powerful effect of reducing disease by smoking cessation. The benefit would be apparent within a few years, because there is a dramatic reduction in risk of heart disease, evident within 1–2 years of smoking cessation. I believe it is within our reach to do much better than the effect predicted by the World Bank, a decrease in tobacco-related deaths of almost 200 000, but the public-health community will need to marshal powerful political allies to impact that projected figure. We need to make it as easy to get treatment for tobacco addiction as it is to get the disease.

In addition to the dramatic impact of smoking cessation, is the delayed, but powerful, effect of preventing initiation. It will have only a minimal effect by 2050, because the main increase in mortality does not begin until about age 50. Therefore, the effect will be apparent about 30–50 years after prevention, as the generation exposed to prevention reaches the age at which smoking-caused diseases begin to escalate

0 100 200 300 400 500

1950 1975 2000 2025 2050

Year

Tobacco deaths (millions)

Baseline

If proportion of young adults taking up smoking halves by 2020

If adult consumption halves by 2020

7

1 2

5 5

3

dramatically. Once more, I am not satisfied with a goal of 50% reduction of initiation, because I think we can do better. If we look at the results of tobacco prevention and ces-sation efforts in California and Massachusetts during the 1990s, we see that smoking initiation and prevalence can be reduced, and it is reasonable to predict even stronger results if the efforts and expenditures were more commensurate with the magnitude of the health problem caused by tobacco (CDC 1999b, 2000). I would also point out that Fig. 1 shows only premature mortality; it does not include the important, and more rapid, benefits of preventing initiation in terms of projected missed days of school, and lost work productivity due to diseases that may not be life threatening, but can be debil-itating and account for unnecessary suffering. Of course, the greatest effect on smoking prevalence in the near and long term would be from the simultaneous reduction of initi-ation and increase in cessiniti-ation, which could have synergistic effects (Farkas et al.1999).

I believe that my vision is possible because we already have the science foundation to support substantial progress. We know enough to predict significant reductions in risk through substantial increases in smoking cessation (US DHHS 1989; World Bank 1999). We have treatments, both behavioral and pharmacological, that can help people quit smoking at far less cost per person and far greater cost benefit than treatment costs of many of the diseases caused by tobacco (Cromwell et al.1997; World Bank 1999). We know that the prevention of initiation of tobacco use can be accomplished by comprehensive educational programs that increase awareness of the harms inherent in smoking, and by decreased access and increased costs at the point of purchase through increased tobacco taxes (Kessler et al.1997; Chaloupka et al.2001; Bachman et al.2002). We have a solid scientific foundation that will allow us to move forward and make considerable progress in the US and globally (WHO 2001).

Realizing the vision

I have already touched upon some of the elements that will be critical to the realization of my vision for the twenty-first century, and many other potential features are dis-cussed in this volume. At this point, I would like to make some general observations that I think are particularly important for focusing our efforts, so that we may achieve our goals.

First, we have to understand that we are fighting disease and Big Tobacco, not ciga-rette smokers. We have to isolate and contain Big Tobacco interests in the interest of health. We have to fight for the resources to support the science that is yet needed, and to support the application of its lessons in order to protect those who do not use tobacco products, and to serve those who are addicted and those who will yet become addicted. We need to work to keep our political leaders on the right path, or the powerful interests of Big Tobacco will surely deliberately lead them astray.

As I have written before, we will have to channel outrage to ensure that, from local communities to the global community, we do not become complacent. Our tasks will

consume all the energy we can muster (Koop 1998a). Consider that on the backs of the approximately 50 million smokers in the United States alone, lawsuit settlements generated a potential monetary pipeline approaching 10 billion US dollars per year for 25 years. But across the nation, the percentage of these funds being used to contain Big Tobacco, to prevent initiation, and to treat the addicted is in the single digits. The decisions to divert the vast majority of those funds have been unconscionably wrong, and I continue to wonder at the relative absence of outrage at this fact (Koop 1998a,b). Perhaps I should not be surprised, because, as I have reviewed previously secret docu-ments from Big Tobacco, I have seen that this is not only an evil industry, it is also one that has ensnared its potential political, regulatory, and legal adversaries as tightly as it has the consumers of its products.

Moving forward will require us to build linkages to isolate and contain Big Tobacco. The linkages we need are many and varied. Global, country, community, and organiza-tional linkages are needed to coordinate policy and political efforts. Linkages among research, education, and service sectors are important to maximize their impact.

In addition to linkages, there is much about the process of initiation and mainte-nance of tobacco addiction that needs to be considered if we are to prevent and treat it more effectively. We need to consider racial, gender, age-related, cultural, and philo-sophical issues to prevent tobacco use, just as Big Tobacco exploits these same charac-teristics to initiate the use of its products. We need to appreciate the fact that once exposed to the pernicious effects of tobacco-delivered nicotine, the structure and function of the brain begins to change, so that tobacco use is not a simple adult choice. It is, in part, a behavioral response to deeply entrenched physiological drives created by years of daily exposure to nicotine during the years of adolescent neural plasticity. This means that tobacco users will need education to guide their decisions and, often, treatment support, to act upon them. Addiction to tobacco-delivered nicotine should be considered the primary disease, to which the major causes of morbidity and prema-ture mortality are secondary. We should treat it no less seriously than we treat conse-quences such as lung cancer and heart disease, because treatment of addiction may help avoid the subsequent need for treatment of lung cancer and heart disease. In fact, such efforts will support prevention because the children of parents who quit smoking are half as likely to initiate, and twice as likely to try quitting if they have already begun (Farkas et al.1999).

it impairs quality of life for years until the killing is accomplished. Similarly, policy makers should care about reduced productivity and economic viability of the work-force, if not the economics of tobacco-caused disease (Warner 2000).

Our efforts to communicate the relevant reasons for freedom from tobacco will be countered by Big Tobacco, and we must resolve to never again let its false and mislead-ing statements go unanswered. We need a strong voice to ensure that policy makers know the truth about the tobacco products of today and tomorrow. We are beginning to see the twenty-first century version of ‘low tar’ cigarettes from the tobacco industry— new products with even stronger allusions to reduced risk, with even less precedent upon which to base policy and reaction. We must not forget the lessons of the twentieth-century products and product promotions that were intended, by Big Tobacco, to address smokers’ concerns, even as they perpetuated the pipeline of death and disease (Kessler 2000). The release of the tobacco industry documents has been a treasure trove for tobacco-control advocates and policy makers alike. It is tantamount to crack-ing the genetic code of the malaria-carrycrack-ing mosquito, or the operational plans of an illicit drug smuggling ring. This inside knowledge does not make our course of actions as clear or as easy as we would like, but it provides a sobering view of what we are up against and what kinds of challenges we face.

Getting the message out

I would like to propose a strategy for ensuring that public perceptions will begin to reflect the truth about tobacco. The experience in California and elsewhere has shown that effective public education strategies can mobilize action, and reduce smoking (Balbach and Glantz 1998). However, to be effective we need to know who the public is, how the public can use our expertise, and what the public should know.

Who?

The public is a diverse patchwork of cultures, each with special languages, values, norms, and expectations. I propose that at least one-third of our strategic planning and daily endeavors be devoted to understanding cultural diversity, protecting human dignity, and helping each ‘public’ develop its own means to become free of tobacco disease.

How?

We can take as a starting point the fact that the information and emotions held by con-sumers with respect to tobacco products are derived heavily from explicit advertising, and implicit purchasing of good will, by Big Tobacco, such as its ‘philanthropic’ efforts to sponsor sporting events, entertainment, charities, and, in some countries, public street signs and traffic signals. Following well-accepted principles of advertising, our message must be simple, consistent, pervasive, repetitious, and delivered through many

sources. It must be framed so that it is interesting and relevant to the intended listeners. Although our motivation may be to reverse the course of death and disease, our message should be upbeat and provide hope and opportunity, rather than the promise of death and disease.

We must engage all manner of organizations that provide for society and its well-being. Even as the tobacco industry has attempted to subvert various organizations, we must reclaim them to serve humanity, and to help disseminate messages of freedom from tobacco and its attendant diseases. There can be no place for turf wars or divisive exer-cises if we are to maximize our effectiveness. Unity should be the watchword, from the level of local community organizations to the World Health Organization. To reach the diverse populations of smokers, we must enlist the support of a diversity of organiza-tions, as measured by culture, ethnicity, and even those with entirely different purposes, ranging from religious organizations to hobby industries, to the entertainment industry.

What?

It is clear that the motivation of Big Tobacco is greed. I believe greed that flourishes at the expense of the destruction of millions of lives a year can only be described as evil; it cannot be reconciled with personal and corporate ethics and morality. Such greed is infectious and pervasive, and in the tobacco industry extends into the realm of finan-cial investment. Those who hold large portfolios such as, colleges, universities, pension plans, etc., by keeping investments in tobacco stock, have convinced themselves that the rules of the marketplace override separation from evil if a profit is to be made. President Reagan called the Soviet Union, ‘the evil empire’, and President George W. Bush referred to Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, as ‘the axis of evil’. Yet these entities to whom evils were attributed have not killed more than 400 000 citizens of the United States, or millions worldwide, each year. The evil empire is Big Tobacco and, unlike military and political enemies who say, ‘I intend to kill you if I can’, Big Tobacco disguises its evil with the invitation to light up, and become alive with pleasure.

documents and through litigation by State attorneys general in the United States and elsewhere.

A place for harm reduction?

Much of public health can be viewed as efforts to reduce disease prevalence and sever-ity by reducing exposures to pathogens, and by treating those exposed. In principle, this approach could be applied to reduce the death and disability caused by tobacco in ongoing tobacco users. This has been discussed elsewhere, and in this volume, with respect to tobacco (Food and Drug Law Institute 1998; Warner et al.1998; Stratton et al. 2000; Henningfield and Fagerstrom 2001; Warner 2001). It is certainly one of the most controversial elements among potential strategies for reducing the risk of death and disease in tobacco users who, despite our best efforts, will be unable to completely abstain from tobacco. We should not ignore their plight anymore than we should ignore the plight of the person who has contracted a tobacco-caused disease. After all, their volitional control over their tobacco use may be little different than their voli-tional control over the expression of cancer in their bodies. Furthermore, if we can reduce their risk of disease despite aspects of their behavior that we cannot control, are we not better off, both as a global community and as individuals? Here again, I draw upon my experience with the HIV epidemic in the United States. Before we were even certain that a virus was the etiological culprit, I, as the nation’s surgeon general, advo-cated strategies to reduce the spread of the disease—strategies ranging from the use of condoms to drug abuse measures, including treatment. Despite our best efforts, we could not eliminate risky sex or drug abuse, but we were able to reduce the spread of the disease by reducing the risk of transmission (Bullers 2001).

The problem with harm reduction approaches is that may pose theoretical benefits to a few individuals, along with real and theoretical risks to many others. This was the experience with smokeless tobacco products in the United States, in which relatively few recalcitrant cigarette smokers may have switched from cigarettes to snuff, incur-ring theoretical (but as yet uncertain) disease reduction, while, at the same time, a new epidemic of smokeless tobacco was observed in young boys, who happened to be athletes (US DHHS 1986). In this domain I concur with the general conclusions of the Institute of Medicine report, which said, in essence, that although there is great poten-tial to reduce disease by harm-reduction methods, none have yet been studied ade-quately to allow their promotion, and those promoted by tobacco companies, in particular, carry substantial risks of worsening the total public health picture by under-mining prevention and cessation (Stratton et al. 2000). This is also an area in which our science needs to be substantially expanded, because, at present, the main body of knowledge pertaining to the potential health effects of tobacco product design and ingredient manipulations seems to reside within Big Tobacco. This has been proven an unreliable source of complete and accurate information. In the future we cannot be held hostage to such a state of affairs.

Concluding comments

I have a vision for public health that is optimistic and realistic. In my lifetime, I have seen the rise and fall of epidemics, and I have come to believe that well-intentioned men and women, motivated by a will to serve and guided by science, can control dis-ease and eradicate plagues. Unlike other epidemics, the disdis-ease of tobacco addiction and its many life-threatening accompaniments has an important ally in Big Tobacco. But no form of institutionalized evil can perpetuate itself for long when the truth about its intentions and methods becomes known. Therefore, it is realistic to believe that we will turn the tide on this epidemic. We will isolate and contain Big Tobacco, and we will see the decline of tobacco-caused disease and disability. We have the foun-dation to make tobacco-caused disease history, and the dawn of the next century a time that, once again, will see lung cancer a relative rarity.

There is not unanimity among those in the profession of public health concerning how Big Tobacco should be brought to its knees. Some public-health advocates believe it is possible to have a dialog with Big Tobacco; this implies that it is possible to negotiate morality with Big Tobacco, even though the industry has deliberately spurned such opportunities for many decades, while using their deceitful data to serve the ends of greed rather than health. These folks in public health, in general, are kind, compassionate, and truly believe that the tobacco industry will eventually come around. It is my belief that nothing is further from the truth. I firmly believe that the aforementioned tactic will never work, but with due diligence, the second tactic might work under carefully orchestrated circumstances.

There is another segment of the public-health profession that has quite a different attitude toward Big Tobacco and thinks that the only way it can be brought to its knees is to destroy it as it presently exists. In days of yore, when military combatants pro-tected themselves with suits of armor, combat was at close quarters, and frequently hand-to-hand. You destroyed your enemy by finding the chink in his armor and through it you thrust your spear, shot your arrow, or guided your blade.

Isn’t it time that public-health people, united, studied the armor of Big Tobacco care-fully, found the chinks therein, and acted accordingly? The tobacco enemy is big, powerful, extraordinarily wealthy, and has learned to practice its deceitful ways over half a century, but the one thing it does not have on its side is righteousness. I do believe that, in the long run, Big Tobacco can be brought to its knees with the combined right-eous outrage of the citizens of the world.

it will not succeed. Now that the truth has leaked out through documents, through research, and through testimony in the courtroom, the clock cannot be turned back and its denials will not hold. Good people will not allow the lies to stand, nor the destructive course to be stayed. Good and dedicated people need to work together, from the voluntary workers in the charitable organizations, to the public-health leaders, and to many leading politicians, who, increasingly, are refusing to take tobacco money and are willing to stand up for public health. The challenge will not be easy, but there is a public-health path, and I predict that many will follow it.

As a doctor, and as the nation’s surgeon general, I learned to be guided by scientific truth, even as I was motivated by basic principles of justice and service to humanity. My appraisal of the state of the science confirms that reducing tobacco-caused disease is an achievable goal, and that continued research can be the supportive companion of our public-health efforts. When the history of the twenty-first century is written, I believe it will be observed that its dawn was the beginning of the end for Big Tobacco and its diseases, and that by its end, lung cancer was once again relegated to the status of a rare disease.

Koop Institute, Dartmouth College C. Everett Koop

References

Bachman, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., Schulenberg, J. E., Johnston, L. D., Bryant, A. L., and Merline, A. C.

(2002).The decline of substance abuse in young adulthood. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey.

Balbach, E. D., and Glantz, S. A.(1998). Tobacco control advocates must demand high-quality media campaigns: The California experience.Tobacco Control,7, 397–408.

Bialous, S. A., and Yach, D.(2001). Whose standard is it, anyway? How the tobacco industry determines the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards for tobacco and tobacco products.Tobacco Control,10, 96–104.

Bradford, J. A., Harlan, W. R., and Hanmer, H. R.(1936). Nature of cigarette smoke. Technic of experimental smoking.Industrial Engineering and Chemistry,28, 836–9.

Bullers, A. C.(2001). Living with AIDS—20 years later.FDA Consumer, November–December. Website: www.fda.gov/fdac/features/2001/601_aids.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999a). Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999.Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,48(12), 241–3.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999b).Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs, August.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000). Declines in lung cancer rates—California, 1988–1997.Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,49(47), 1066–9.

Chaloupka, F. J., Wakefield, M., and Czart, C.(2001). Taxing tobacco: The impact of tobacco taxes on cigarette smoking and other tobacco use. In:Regulating Tobacco,(ed. R. L. Raabin and S. D. Sugarman), pp. 39–71. Oxford University Press, New York.

Corti, C.(1931).A history of smoking. George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd., London.

Cromwell, J., Bartosch, W. J., Fiore, M. C., Hasselblad, V., and Baker, T.(1997). Cost-effectiveness of the clinical practice recommendations in the AHCPR guideline for smoking cessation.Journal of the American Medical Association,278,1759–66.

Fairclough, G.(2000). Smoking’s next battleground.Wall Street Journal, B1 and B4.

Farkas, A. J., Distefan, J. M., Choi, W. S., Gilpin, E. A., and Pierce, J. P.(1999). Does parental smoking cessation discourage adolescent smoking? Preventive Medicine,28, 213–18.

Food and Drug Law Institute (1998). Special Issue: Tobacco dependence: innovative regulatory approaches to reduce death and disease.Food and Drug Law Journal,53(Suppl.), 1–137.

Garrett, B. E., Rose, C. A., and Henningfield, J. E.(2001). Tobacco addiction and pharmacological interventions.Expert Opinion in Pharmacotherapy,2, 1545–55.

Givel, M. S., and Glantz, S. A.(2001). Tobacco lobby political influence on U.S. state legislatures in the 1990s.Tobacco Control,10, 124–34.

Henningfield, J. E., and Fagerstrom, K. O.(2001). Swedish match company, Swedish snus and public health: a harm reduction experiment in progress? Tobacco Control,10, 253–7.

Hirschhorn, N.(2000). Shameful science: four decades of the German tobacco industry’s hidden research on smoking and health.Tobacco Control,9,242–7.

Hirschhorn, N., Bialous, S. A., and Shatenstein, S.(2000). Phillip Morris’ new scientific initiative: an analysis.Tobacco Control,10,247–52.

Hurt, R. D., and Robertson, C. R.(1998). Prying open the door to the tobacco industry’s secrets about nicotine: The Minnesota Tobacco Trial.Journal of the American Medical Association,

280, 1173–81.

Kessler, D. A.(2000).A question of intent: a great American battle with a deadly industry. Public Affairs, New York.

Kessler, D. A., Witt, A. M., Barnett, P. S., Zeller, M. R., Natanblut, S. L., Wilkenfeld, J. P.,et al.(1996). The Food and Drug Administration’s regulation of tobacco products.New England Journal of Medicine,335, 988–94.

Kluger, R.(1996).Ashes to ashes. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Koop, C. E.(1998a). The tobacco scandal: Where is the outrage? Tobacco Control,7, 393–6.

Koop, C. E.(1998b). Don’t forget the smokers.Washington Post, Sunday 8 March, C7.

National Cancer Institute (1996).The FTC cigarette test method for determining tar, nicotine, and car-bon monoxide yields of U.S. cigarettes: Report of the NCI expert committee. Smoking and tobacco control monograph No. 7.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

National Cancer Institute (2001).Risks associated with smoking cigarettes with low-machine measured yields of tar and nicotine, Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph, No. 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, NIH Pub. No. 02–5074, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

Orey, M.(1999).Assuming the risk: The mavericks, the lawyers, and the whistle-blowers who beat Big Tobacco. Little, Brown and Co., New York.

Slade, J.(2000). Innovative nicotine delivery devices from tobacco companies. In:Nicotine and public health (ed. R. Ferrence, J. Slade, R. Room, and M. Pope), pp. 209–28. American Public Health Association, Washington.

Slade, J., Bero, L. A., Hanauer, P., Barnes, D. E., and Glantz, S. A.(1995). Nicotine and addiction. The Brown and Williamson documents.Journal of the American Medical Association,

Stratton, K., Shetty, P., Wallace, R., and Bondurant, S.(ed.) (2000).Clearing the smoke: Assessing the science base for tobacco harm reduction. National Academy Press, Washington.

Taylor, P.(1984).The smoke ring. Pantheon Books, New York.

Thun, M. J. and Burns, D. M.(2001). Health impact of ‘reduced yield’ cigarettes: A critical assessment of the epidemiological evidence.Tobacco Control,10(Suppl.), i4–11.

US DHHS (US Department of Health and Human Services) (1988).The health consequences of smok-ing: nicotine addiction. A report of the Surgeon General.DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 88–8406, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington.

US DHHS (US Department of Health and Human Services) (1989).Reducing the health consequences of smoking: 25 years of progress. A report of the Surgeon General.DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 89–8411, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington.

Warner, K. E.(2000). The economics of tobacco: myths and realities.Tobacco Control,9, 78–89.

Warner, K. E.(2001). Reducing harm to smokers: methods, their effectiveness, and the role of policy. In:Regulating tobacco (ed. R. L. Raabin and S. D. Sugarman), pp. 111–42. Oxford University Press, New York.

Warner, K. E., Peck, C. C., Woosley, R. L., Henningfield, J. E. and Slade, J.(1998). Preface to Tobacco dependence: Innovative regulatory approaches to reduce death and disease.Food and Drug Law Journal,53(Suppl.), 1–16.

Wilkenfeld, J., Henningfield, J. E., Slade, J., Burns, D., and Pinney, J. M.(2000). It’s time for a change: cigarette smokers deserve meaningful information about their cigarettes.Journal of the National Cancer Institute,92, 90–2.

White, L. C.(1988).Merchants of death. Beech Tree Books, New York.

World Bank (1999).Curbing the epidemic: Governments and the economics of tobacco control. World Bank, Washington.

World Health Organization (2001).Advancing knowledge on regulating tobacco products.World Health Organization, Geneva.

Wynder, E. L.(1997). Tobacco as a cause of cancer: Some reflections.American Journal of Epidemiology,146,687–94.

Preface v

C. Everett Koop

Contributors xxiii

Abbreviations xxix

Introduction xxxi

Tobacco: History

1 Evolution of knowledge of the smoking epidemic 3

Richard Doll

2 The great studies of smoking and disease in the twentieth century 17

Michael J. Thun and Jane Henley

3 Dealing with health fears: Cigarette advertising in the United States in the twentieth century 37

Lynn T. Kozlowski and Richard J. O’Connor

Tobacco: Composition

4 The changing cigarette: Chemical studies and bioassays 53

Ilse Hoffman and Dietrich Hoffmann

5 Tobacco smoke carcinogens: Human uptake and DNA interactions 93

Stephen S. Hecht

Nicotine and addiction

6 Pharmacology of nicotine addiction 129

Jack E. Henningfield and Neal L. Benowitz

7 Behavioral pharmacology of nicotine reinforcement 149

Bridgette E. Garrett, Linda Dwoskin, Michael Bardo and Jack E. Henningfield

8 Cigarette science: Addiction by design 167

Jeff Fowles and Dennis Shusterman

9 Nicotine dosing characteristics across tobacco products 181

Mirjana V. Djordjevic

Tobacco use: Prevalence, trends, influences

10 Tobacco in Great Britain 207

11 The epidemic of tobacco use in China 215

Yang Honghuan

12 Patterns of smoking in Russia 227

David Zaridze

13 Tobacco smoking in central European countries: Poland 235

Witold Zato´nski

14 The epidemic in India 253

Prakash C. Gupta and Cecily S. Ray

15 Tobacco in Africa: More than a health threat 267

Yussuf Saloojee

Tobacco and health. Global burden

16 The future worldwide health effects of current smoking patterns 281

Richard Peto and Alan D. Lopez

17 Passive smoking and health 287

Jonathan M. Samet

18 Adolescent smoking 315

John P. Pierce, Janet M. Distefan, and David Hill

19 Tobacco and women 329

Amanda Amos and Judith Mackay

Tobacco and cancer

20 Cancer of the prostate 355

Fabio Levi and Carlo La Vecchia

21 Laryngeal cancer 367

Paolo Boffetta

22 Smoking and cancer of the oesophagus 383

Eva Negri

23 Tobacco use and risk of oral cancer 399

Tongzhang Zheng, Peter Boyle, Bing Zhang, Yawei Zhang, Patricia H. Owens, Qing Lan and John Wise

24 Smoking and stomach cancer 433

David Zaridze

25 Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer 445

Edward Giovannucci

26 Smoking and cervical neoplasia 459

27 Tobacco and pancreas cancer 479

Patrick Maisonneuve

28 Smoking and lung cancer 485

Graham G. Giles and Peter Boyle

29 Tobacco smoking and cancer of the breast 503

Dimitrios Trichopoulos and Areti Lagiou

30 Smoking and ovarian cancer 511

Crystal N. Holick and Harvey A. Risch

31 Endometrial cancer 523

Paul D. Terry, Thomas E. Rohan, Silvia Franceschi and Elisabete Weiderpass

Tobacco and heart disease

32 Tobacco and cardiovascular disease 549

Konrad Jamrozik

Tobacco and respiratory disease

33 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 579

David M. Burns

Tobacco and other diseases

34 Smoking and other disorders 593

Allan Hackshaw

Genetics, nicotine addiction, and smoking

35 Genes, nicotine addiction, smoking behaviour and cancer 623

Michael Murphy, Elaine C. Johnstone and Robert Walton

Tobacco and alcohol

36 Tobacco and alcohol interaction 643

Albert B. Lowenfels and Patrick Maisonneuve

Tobacco control: Successes and failures

37 Global tobacco control policy 659

Nigel Gray

38 Lessons in tobacco control advocacy leadership 669

Michael Pertschuk

39 A brief history of legislation to control the tobacco epidemic 677

Ruth Roemer

40 Roles of tobacco litigation in societal change 695

Richard A. Daynard

41 Impact of smoke-free bans and restrictions 707

Ron Borland and Claire Davey

42 Effective interventions to reduce smoking 733

Prabhat Jha, Hana Ross, Marlo A. Corrao and Frank J. Chaloupka

Treatment of dependence

43 Treatment of tobacco dependence 751

Michael Kunze and E. Groman

44 Regulation of the cigarette: Controlling cigarette emissions 765

Nigel Gray

Amanda Amos

Reader in Health Promotion Division of Community Health

Sciences Medical School

University of Edinburgh Teviot Place, Edinburgh EH8 9AG, UK

Michael Bardo

Department of Pharmacology University of Kentucky Lexington, Kentucky, USA

Neal L. Benowitz Professor and Chair

Division of Clinical Pharmacology University of California

1001 Potrero Avenue Building 30, Room 3316

San Francisco, CA 941110, USA

Paolo Boffetta

Unit of Analytical Epidemiology International Agency for Research on

Cancer

150 cours Albert-Thomas 69372 Lyon cedex 08, France

Ron Borland Director

Cancer Control Research Institute 100 Drummond Street

Carlton Victoria 3053 Australia

Peter Boyle

Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics

European Institute of Oncology Via Ripamonti 435, 20141 Milan, Italy

David M. Burns

Professor of Family and Preventive Medicine

UCSD School of Medicine 1545 Hotel Circle So., Suite 310 San Diego, CA 92108, USA

Frank J. Chaloupka Research Associate

Health Economics Program, NBER 850 West Jackson Boulevard Suite 400, Chicago

IL 60607, USA

Marlo A. Corrao Program Manager

Tobacco Control Country Profiles Epidemiology and Surveillance Research American Cancer Society (ACS) 1599 Clifton Road NE, Atlanta, GA, 30329-4251, USA

Jack Cuzick

Department of Mathematics, Statistics and Epidemiology

Cancer Research UK, London, UK

Claire Davey Research Officer

Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, The Cancer Council Victoria, Australia

Richard A. Daynard

Northeastern University School of Law 400 Huntington Avenue

Boston, MA 02115, USA

Mirjana V. Djordjevic Bioanalytical Chemist Behavioral Research Program Tobacco Research Control Branch National Cancer Institute

6130 Executive Boulevard, MSC 7337 Executive Plaza North

Bethesda,Maryland 20892, USA

Richard Doll

Clinical Trial Service Unit & Epidemiological Studies Unit Harkness Building, Radcliffe

Infirmary

Oxford OX2 6HE, UK

Linda Dwoskin

Department of Pharmacology University of Kentucky Lexington, Kentucky, USA

Jeff Fowles

Population and Environmental Health Group

Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR), Limited

PO Box 50-348, Porirua New Zealand

Silvia Franceschi

International Agency for Research on Cancer

Unit of Field and Intervention Studies 150 Cours Albert Thomas

69372 Lyon Cedex 08, France

Bridgette E. Garrett

Office on Smoking and Health National Center for Chronic Disease

Prevention and Health Promotion

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Atlanta, GA 30341, USA

Graham G. Giles

Cancer Epidemiology Centre The Cancer Council Victoria 1 Rathdowne Street, Carlton Victoria 3053, Australia

Edward Giovannucci

Departments of Nutrition and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health

Boston, MA 02115, USA

Nigel Gray

Senior Research Associate Division of Epidemiology and

Biostatistics

European Institute of Oncology Milan, Italy

E. Groman Associate Professor

Institute of Social Medicine Medical University of Vienna Rooseveitplatz 3

A 1090 Vienna, Austria

Prakash C. Gupta Senior Research Scientist Epidemiology Research Unit

Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Homi Bhabha Road

Mumbai 400 005, India

Allan Hackshaw Deputy Director Cancer Research UK

and University College London Cancer Trials Centre

Stephenson House

xxv

Stephen S. Hecht

University of Minnesota Cancer Center

Mayo Mail Code 806, 420 Delaware St SE Minneapolis MN 55455, USA

Jane Henley

Dept. Epidemiology and Surveillance Research

American Cancer Society 1599 Clifton Road

Atlanta, GA 30329-4251, USA

Jack E. Henningfield

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore,Maryland, USA

David Hill

Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria 100 Drummond Street

Carlton Victoria 3053 Australia

Dietrich Hoffmann

American Health Foundation 1 Dana Road

Valhalla, New York, NY 10595, USA

Ilse Hoffmann

American Health Foundation 1 Dana Road

Valhalla, New York, NY 10595, USA

Crystal N. Holick

Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, 677 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA

Yang Honghuan

Professor of Research Center of NCD & BRFS and Dept. of Epidemiology Chinese Academy of Medical Science

Peking Union Medical College 5# Dong Dan San Tiao Beijing 100005, PR China

Konrad Jamrozik Professor of Primary Care

Epidemiology

Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine

Reynolds Building, St Dunstan’s Road London W6 8RP, UK

Prabhat Jha

Canada Research Chair in Health and Development,

Centre for Health Development University of Toronto

30 Bond Street

Toronto, M5B 1W8, Canada

Elaine C. Johnstone CRUK GPRG

Clinical Pharmacology Radcliffe Infirmary,

Oxford OX2 6HE, UK

C. Everett Koop

Koop Institute, Dartmouth College Hanover, NH 03755-3862, USA

Lynn T. Kozlowski

Department of Biobehavioral Health Penn State University

University Park, PA 16802, USA

Michael Kunze

Professor of Public Health Institute of Social Medicine Medical University of Vienna Rooseveltplatz 3, A-1090 Vienna, Austria

Areti Lagiou

Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology, School of Medicine University of Athens, Greece

Qing Lan

Division of Epidemiology and Genetics

National Cancer Institute, Bethesda MD 20892, USA

Carlo La Vecchia

Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”, Via Eritrea 62 20157 Milano, Italy

Fabio Levi

Registres Vaudois et Neuchâtelois des Tumeurs

Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois Falaises 1, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland

Alan D. Lopez

World Health Organization Geneva, Switzerland

Albert B. Lowenfels Professor of Surgery New York Medical College Munger Pavilion

Valhalla, NY, 10595, USA

Judith Mackay Director

Asian Consultancy on Tobacco Control

Riftswood, 9th Milestone

DD 229, Lot 147, Clearwater Bay Road Kowloon, Hong Kong

Patrick Maisonneuve

Director Clinical Epidemiology Program

Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics

European Institute of Oncology Via Ripamonti 435

20141 Milan, Italy

Michael Murphy University of Oxford Department of Paediatrics Childhood Center Research Group 57 Woodstock Road

Oxford OX2 6HJ, UK

Eva Negri

Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”

Via Eritrea 62, 20157 Milano, Italy

Richard J. O’Connor

Department of Biobehavioral Health Penn State University

University Park, PA 16802, USA

Patricia H. Owens

Department of Epidemiology and Public Health

Yale School of Medicine New Haven, CT, USA

Michael Pertschuk Co-Director Advocacy Institute 1629 K Street, NW

Washington DC 20005, USA

Richard Peto

Clinical Trial Service Unit & Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU)

Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, OX2 6HE, UK

John P. Pierce

Sam M.Walton Professor of Cancer Research

Associate Director for Cancer Prevention and Control

xxvii

Cecily S. Ray Project Assistant Epidemiology Research Tata Memorial Centre Dr. E. Borges Marg, Parel Mumbai, 400 012 India

Harvey A. Risch

Department of Epidemiology and Public Health,

Yale University School of Medicine, 60 College Street,

PO BOX 208034, New Haven, CT 06520-8034, USA

Ruth Roemer

Adjunct Professor Emerita School of Public Health University of California

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772, USA

Thomas E. Rohan

Department of Epidemiology and Social Medicine

Albert Einstein College of Medicine 1300 Morris Park Avenue, 13th Floor Bronx, NY 10461, USA

Hana Ross Associate Director

International Tobacco Evidence Network 850 West Jackson Boulevard, Suite 400 Chicago, Illinois 60607, USA

Yussuf Saloojee

Coordinator, International

Non Governmental Coalition Against Tobacco

P O Box 1242, Houghton 2041 South Africa

Jonathan M. Samet

Department of Epidemiology and the Institute for Global Tobacco Control Bloomberg School of Public Health

Johns Hopkins University 615 N.Wolfe St., Suite 6041 Baltimore, MD 21205, USA

Dennis Shusterman

Upper Airway Biology Laboratory 1301 So. 46th Street, Bldg. 112 Richmond, CA 94804, USA

Anne Szarewski Clinical Consultant Cancer Research

UK Centre for Epidemiology, Mathematics and Statistics

Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine London ECIM 6BQ, UK

Paul D. Terry

NIEHS, Epidemiology Branch, PO BOX 12233,

MD A3-05, USA

Michael J. Thun

Dept. of Epidemiology and Surveillance Research

American Cancer Society Atlanta, GA 30329-4251, USA

Dimitrios Trichopoulos Department of Epidemiology Harvard School of Public Health 677 Huntington Avenue

Boston, MA 02115, USA

Robert Walton CRUK GPRG

Clinical Pharmacology Radcliffe Infirmary Oxford OX2 6HE, UK

Elisabete Weiderpass

International Agency for Research on Cancer

Unit of Field and Intervention Studies 150 Cours Albert Thomas

69372 Lyon Cedex 08, France

Patti White

Public Health Adviser Health Development Agency Trevelyan House

30 Great Peter Street London SWIP 2HW, UK

John Wise

Laboratory of Environmental and Genetic Toxicology

Bioscience Research Institute University of Southern Maine Portland, ME, USA

David Zaridze Director

Institute of Carcinogenesis

N.N. Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Center, 24 Kashirskoye Shosse 115478,Moscow, Russia

Witold Zato´nski

The Maria Sklodowska - Curie Cancer Center and Institute of Oncology

Department of Epidemiology and Cancer Prevention

Warsaw, Poland

Bing Zhang

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics,McGill University Montreal, Canada, H3A 1A2

Yawei Zhang

Department of Epidemiology and Public Health

Yale School of Medicine New Haven, CT, USA

Tongzhang Zheng Associate Professor

Department of Epidemiology and Public Health

AAA Abdominal aortic aneurysm AC Adenocarcinoma

ACO Adenocarcinoma of the esophages ACS American Cancer Society AMI Acute myocardial infarction APA The American Psychiatric

Association

ARCI Addiction Research Centre Inventory

ASH Action on Smoking and Health BAT British America Tobacco BMI Body mass index

BPDE anti-7,8-dihydroxy-9,10-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene BaA benz(a)anthracene

BaP benzo(a)pyrene

CDC Centers for Disease Control CDCP Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention

CHD Cardiovascular disease CI Confidence interval

CIN Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia CO Carbon monoxide

COLD Chronic obstructive lung disease COMT Catechol O-methyl transferase COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease

CORESTA Centre De Cooperation Pour Les Recherches Scientifiques Relative Au Taba

COX cyclooxygenase

CPP Conditioned place preference CPS Cancer Prevention Study CVD Cardiovascular disease CeVD Cerebrovascular disease DATI Dopaminergic transporter DBH Dopamine β-hydroxylase DHEAS Dehydroepiandrosterone DMBA 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene

DSM Diagnostic and statistical manual DVT Deep vein thrombosis

EPHX1 Epoxide hydrolase

ETS Environmental tobacco smoke EU European Union

FCTC Framework Convention of Tobacco Control

FDA Food and Drug Administration FISH Fiter in situhybridization FSH Follicle-stimulating hormone FTC Federal Trade Commission FTND Fagerström test for tobacco

dependence

FTQ Fagerström tolerance questionnaire FUBYAS First usual brand adult smoker GC Gas chromatography GC-TEA Gas chromatography with

nitrosamine-selective detection GC–MS Gas chromatography–mass

spectrometry GNP Gross national product GRAS Generally regarded as safe GSTs Glutathione S-transferases GYTS Global youth tobacco survey HEA Health Education Authority HIV Human Immunodeficiency virus 1-HOP 1-Hydroxypyrene

HPB 4-Hydroxy-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

HPLC High-performance liquid chromatography HPV Human papillomavirus HRT Hormone replacement therapy HSC Human smoking conditions HSV Herpes simplex virus Hb hemoglobin

IARC International Agency for Research on Cancer

IC Intermittent claudication

ICD The International Classification of Diseases

IHD Ischaemic heart disease

ILO International Labour Organization IPCS International programme on

clinical safety

ISO International Standards Organization

LH Luteinizing hormone LLETZ Large Loop Excision of the

Transformation Zone

MBG Morphine-Benzedrine group scale MMP-1 Matrein metalloproteinase-1 gene MRFIT Multiple risk factor intervention

trial

MS Mainstream smoke OR mass spectrometry

MSA Master Settlement Agreement nAChRs nicotinic acetylcholine receptors NATs N-acetyl transferase

NHMRC National Health and Medical Research Council

NNAL 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol NNK

4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-2-butanone NNN N′-nitrosonornicotine NOx nitrogen oxides (NO, NO2, and

N2O)

NPYR N-Nitrosopyrrolidine NRT Nicotine replacement therapy NSDNC Nocturnal sleep-disturbing nicotine

craving

OC Oesophageal cancer OECD Organization for Economic

Collaboration and Development 2-OEH1 2-hydroxyestrone

16α-OEH1 16-α-hydroxyestrone OTC Over-the-counter PAD Peripheral arterial disease PAHs Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

PAHs polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons

PAR Population attributable risk PCR Polymerase chain reaction PCSS Perter community stroke study PE Pulmonary embolism PG Propylene glycol POMS Profile of mood state PREPS Potential reduced-exposure

products

PlCH Primary intracerebral haemorrhage QTL Quantitative trait loci RR relative risk

RT reconstituted tobacco s.c. subcutaneous

SAH Subarachnoid haemorrhage SCC Squamous cell carcinoma SHBG Sex-hormone binding globulin SIDS sudden infant death syndrome SS sidestream smoke

SSA sub-Saharan Africa

TAMA Tobacco Association of Malawi TEAM Total exposure assessment

methodology

TIA Transient cerebral ischaemic attach

TPLP Tobacco products liability project

trans-anti

-BaP-tetraol r-7,t-8,9,c-10-tetrahydroxy-7,8, 9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene TSNAs Tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines UICC International union against

cancer

The publication of this book is timely. Over fifty years after the establishment of the substantial evidence that tobacco caused a great deal of serious disease we are about halfway through the global tobacco epidemic. Declines in consumption and mortality in (some) developed countries are being matched by increases in the developing world, but it seems likely that global tobacco consumption may have reached its peak and be starting to decline.

The severity and social costs of this epidemic are defined clearly now and are covered in the relevant chapters. The reader will probably come to share the editors’ wonder that such a controllable man-made epidemic, of complex diseases but simple aetiology, has resisted public health attempts to control it for so long.

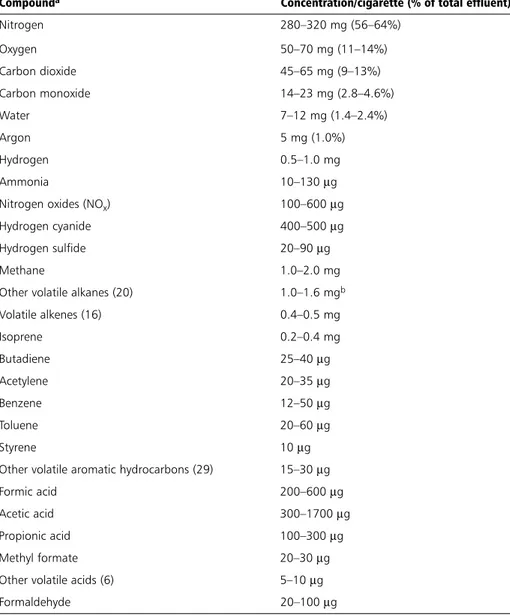

The scientific understanding of tobacco, tobacco smoke, and the relationships with disease are now well understood and new factual knowledge in these fields is unlikely to change this greatly. The major toxic and carcinogenic components of smoke are known and the mechanisms by which these substances cause disease is becoming clear. Knowledge exists which, if applied, could reduce the disease-causing potential of tobacco. Although it is clear that no safe cigarette will ever be manufactured, less dan-gerous variants and other forms of nicotine delivery systems are either here or on the horizon, albeit not at the stage where they can compete with current tobacco products for the global nicotine addiction market.

The chemistry and physiology of nicotine are well documented and the addictive properties of the drug well delineated. The mechanism of addiction is reasonably well understood even though there remains much to learn about methods of treatment and whether there is a substantial genetic contribution towards susceptibility to addiction.

Why, then, is progress against tobacco use and mortality so slow?

The answer lies in the sections devoted to prevalence, policy, and tobacco-related behaviour. A further component of the answer lies in the societal failings of our politi-cal systems to deal with the corrupting effects of tobacco industry’s behaviour, and to focus on preventing what is preventable about the factors contributing to initiation of the habit. Another failure is the lack of effort committed to stimulating cessation efforts which offer the greatest promise of early (i.e. within one to two decades) mor-tality decreases, associated with consideration of better sources of competitive nicotine delivery products.

This book sets out to cover the known levers which could be pulled to reduce tobacco’s death toll. The information in it will be useful to any student or practitioner of medicine and other health sciences who will gain an understanding of the crucial

relationships between science and policy, plus a realistic appraisal of the difficulties which must be overcome before policy is actually applied in the marketplace.

Only when the knowledge we have is used will this most devastating epidemic be brought to a close. This challenge is global.

Part 1

Chapter 1

Evolution of knowledge of the

smoking epidemic

Richard Doll

Introduction

Tobacco was grown and used widely in North, Central and South America for two to three millennia before being introduced to Europe at the end of the fifteenth century. Its use was promoted initially for medicinal purposes, for the treatment of a variety of conditions from cough, asthma, and headaches to intestinal worms, open wounds, and malignant tumours, when it was prescribed to be chewed, taken nasally as a powder, or applied locally.

The use of tobacco for pleasure was discouraged by Church and State and it was not until the end of the sixteenth century that it came to be smoked widely in Europe, at first in pipes in Britain, where it was popularized by Sir Walter Raleigh. Here it became so common that by 1614 there are estimated to have been some 7000 retail outlets in London alone (Laufer 1924). Attempts to ban its use for recreational purposes were made in Austria, Germany, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, India, and Japan, but prohibi-tion was invariably flouted and control by taxaprohibi-tion came to be preferred. This eventu-ally proved to be such an important source of revenue that, in 1851, Cardinal Antonelli, Secretary to the Papal States, ordered that the dissemination of anti-tobacco literature was to be punished by imprisonment (Corti 1931).

Gradually, the way in which tobacco was most commonly used changed. By the end of the seventeenth century, its use as nasal snuff had spread from France, largely replac-ing pipe smokreplac-ing. This practice remained common until a century later, when it, in turn, began to be replaced by the smoking of cigars, which had long been smoked in a primitive form in Spain and Portugal. By then cigarettes were already being made in South America and their use had spread to Spain, but it was not until after the Crimean War that they began to be at all widely adopted. They were made fashionable in Britain by officers returning from the Crimea, and by the end of the nineteenth century ciga-rettes had begun to replace cigars. Consumption in this form increased rapidly during the First World War, and by the end of the Second World War cigarettes had largely replaced all other tobacco products in most developed countries.

who came to consult them, to put them at their ease. Women began to smoke in large numbers much later, except in New Zealand, where, by the end of the nineteenth cen-tury, Maori women were commonly smoking pipes. Then, in the 1920s, women began to smoke cigarettes, at first in the USA and then in Britain, where the practice gained popularity during the Second World War, as an increasing proportion of women began to work outside the home and have an independent income. However, in many other developed countries, women have begun to smoke in large numbers only in the past few decades.

The reason for the swing to cigarettes

The important change in the use of tobacco, for its impact on health, was the swing to cigarettes. This was brought about by two industrial developments. The first was a new method of curing tobacco. With the old method, the smoke that had come from pipes and cigars was alkaline, irritating, and difficult to inhale. However, the nicotine in it was predominantly in the form of a free base which could be absorbed across the oral and pharyngeal mucosa. Blood levels of nicotine could consequently be high and addiction was readily produced; but only small amounts of other constituents were absorbed. The new method, called flue-curing, was introduced in North Carolina in the mid-nineteenth century (Tilley 1948). It exposed the leaf to high temperatures and increased its sugar content, which caused the pH of the smoke to be acid. In this envi-ronment, the nicotine was predominantly in the form of salts and was dissolved in smoke droplets, which were less irritating than the free base and easier to inhale. With each inhalation there was a rapid rise in the level of nicotine in the blood, which was perceived in the brain, and was particularly satisfying to the addict, but other constituents of the smoke were also absorbed and distributed throughout the body.

The second development was mechanical: namely, the introduction of cigarette-making machines. One was patented in 1880, and was eventually adapted by the Duke family to work so efficiently that 120 000 cigarettes of good quality could be produced every 10 hours by one machine, the equivalent of the production of about 100 unassisted workers. As a result, the price fell and a mass market became feasible.

The impact of tobacco on health

However, little attention was paid to these effects by clinicians, who characterized can-cer of the lip as the result of smoking clay pipes, which was a custom of agricultural workers. When, as a medical student in the mid-1930s, I asked the senior surgeon at my teaching hospital whether he thought pipe smoking or syphilis was a cause of cancer of the tongue, he replied that he didn’t know, but that the wise man should certainly avoid the combination of the two.

However, one disease was unequivocally attributed to tobacco, and taught as being so: namely, tobacco amblyopia. It was described by Beer in 1817, and occurred in heavy pipe-smokers in combination with malnutrition. It was probably caused by the cyanide in smoke not being detoxified because of a deficiency of vitamin B12(Heaton et al.1958). The disease is no longer seen, at least in developed countries.

The early impact of cigarette smoking

With the advent of the twentieth century, several new diseases began to be associated with smoking: first, intermittent claudication, which was described by Erb in 1904 and then, in 1908, a rare form of peripheral vascular disease affecting relatively young peo-ple, which Buerger called thrombo-angiitis obliterans, and which has subsequently been named after him. It is now recognized that both diseases were made much more common by smoking, with the latter almost limited to smokers, but neither reached the epidemic proportions that two other, relatively new, diseases achieved in the next few decades.

One of these was coronary thrombosis or, as we would now prefer to say, myocardial infarction. It was first described at autopsy in 1876 (Hammer 1878), although it had certainly occurred earlier, and it was not diagnosed in life until 1910, when it was diag-nosed by Herrick (1912) in Chicago. Subsequently it was reported progressively more often every year for four or five decades. As early as 1920, Hoffman, an American stat-istician, linked the increase in coronary thrombosis with the increasing consumption of cigarettes. Several clinical studies of the relationship between the disease and smok-ing were published, but the findsmok-ings were confused, and no substantial evidence was obtained until 1940, when English et al.reported finding an association in the records of the Mayo Clinic. Their findings led them to conclude that the smoking of tobacco probably had ‘a more profound effect on younger individuals owing to the existence of relatively normal cardiovascular systems, influencing perhaps the earlier development of coronary disease’. However, they eschewed reference to causation, because the sub-ject would be controversial, adding perceptively that ‘Physicians are not yet ready to agree on this important subject’. That cigarette smoking played a part in the increasing incidence of the disease was eventually clearly demonstrated. The association was not close enough for it to have been the only cause of the increase, or even probably the most important, and, unlike the other disease that burst into medical prominence in the first half of the twentieth century, the full explanation of its rapid increase is still a matter for debate (Doll 1987).

The other disease was, of course, cancer of the lung. Until then it had been thought to be exceptionally rare. A small cluster of cases in tobacco workers in Leipzig had led Rottmann to suggest, in 1898, that the disease might be caused by the inhalation of tobacco dust. The first suggestion that it might be due to smoking was not made until 14 years later, by Adler (1912), who noted that, although the disease was still rare, it appeared to have become somewhat less so in the recent past. Many people were subse-quently struck by the parallel increase in the consumption of cigarettes and the inci-dence of the disease and by the frequency with which patients with lung cancer described themselves as heavy smokers, several even ventured to suggest that the two were related (Tylecote 1927; Lickint 1929; Hoffman 1931; Arkin and Wagner 1936; Fleckseder 1936; Ochsner and de Bakey 1941). However, few believed it. Koch’s postu-lates, which were taught as criteria for determining causality, could not be satisfied, as one required the agent to be present in every case of the disease and cases certainly occurred in non-smokers. Moreover, pathologists generally failed to produce cancer experimentally by the application of tobacco tar to the skin of animals. Only Roffo (1931), in Argentina, succeeded in doing so, and his results were discounted in the United Kingdom and the United States because he had produced the tar by burning the tobacco at unrealistically high temperatures. However, diagnostic methods had certainly improved, notably the widespread use of radiology and bronchoscopy, and the idea that the increase in the incidence of the disease was an artefact of improved diagnosis came to be widely believed.

Three case-control studies that were carried out in Germany and The Netherlands between 1939 and 1948 should have focused attention on smoking, as all three suggest-ed, albeit on rather inadequate grounds (Doll 2001), that smoking was a possible cause of lung cancer. However, the war distracted attention from the German literature (Müller 1939; Schairer and Schöniger 1943), and the Dutch paper (Wassink 1948) was published in Dutch and not noticed widely for several years. Outside Germany, smok-ing was still commonly regarded as havsmok-ing only minor effects as late as 1950, and inside Germany, where chronic nicotine poisoning had been thought to produce effects in nearly every system, the reaction against the Nazis brought with it a reaction against their antagonism to tobacco—for propaganda against the use of tobacco had been a major plank in the public health policy of the Nazi government (on the grounds that it damaged the national germ plasm and that addiction to it detracted from obedience to the Führer) (Proctor 1999).

The 1950 watershed

lung’ (Doll and Hill 1950). The results were given wide publicity, but the conclusion was not widely believed. Medical scientists had as yet to appreciate the power of epi-demiology in unravelling the aetiology of non-infectious disease.