Sui Dialect Research

Edited by

Sui Dialect Research

Originally published in Chinese

as Shuiyu Diaocha Yanjiu

水语调查研究,

by Guizhou People’s Press, Guiyang, 2014

Edited by

Andy Castro and Pan Xingwen

Contributors

Andy Castro, Pan Xingwen, Lu Chun, Wei Shifang, Shi Guomeng,

Catherine Ching-yee Castro, Emily Wang Yongzhen, Melissa Partida

A joint research project between

Sandu Sui Autonomous County Sui Research Institute

and

Southwestern Minorities Languages and Culture Research Institute,

Guizhou University and SIL International, East Asia Group

SIL e-Books 66

2015 SIL International®

ISSN: 1934-2470

Fair-Use Policy:

Books published in the SIL e-Books (SILEB) series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes free of charge (within fair-use guidelines) and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s).

Editor-in-Chief Mike Cahill Volume Editor

Becky Quick Managing Editor

iii

Abstract

The Sui are an official minority group of China with a population of around 430,000. The Sui language belongs to the Kam-Sui branch of the Tai-Kadai language family.

This research presents the results of a large-scale survey of the Sui language. The goals of the survey were to document the Sui dialect situation and to elucidate the genetic and synchronic relationships among the various dialects. A 600-item wordlist was collected from sixteen data points. Comprehension of four Sui dialects was also tested across the region using Recorded Text Tests (RTTs).

Based on the primary data and on Thurgood’s (1988) Proto-Kam-Sui, and drawing on related languages as well as various other reconstructions, this work first charts the historical development of the Sui dialects. Secondly, it maps out dialect groups based on synchronic lexical similarity. Thirdly, it applies Levenshtein distance analysis to the data and describes the resulting dialect groups. Finally, it describes and discusses RTT methodology and results. The report also includes wordlist data, phonology sketches for each data point, and interlinearised RTT texts.

The results show that Sui has four main dialects and that one of these is genetically more closely affiliated to Kam than to Sui. Additionally, three dialects have low mutual intelligibility. Mutual intelligibility of dialects is not completely predicted by genetic relationships.

Some items of particular interest in this work include: 1) evidence for sesquisyllabic words in Proto-Kam-Sui (supporting Pittayaporn 2009); 2) evidence for the areal diffusion of tonal flip-flops (Yue-Hashimoto 1986); and 3) an innovative L2 retelling method for testing inter-dialect intelligibility.

This report was originally published in print under the title of Shuiyu Diaocha Yanjiu by Guizhou People’s Press, 2014. The English version of this book is published with permission of Guizhou People’s Press. The maps in this book were produced by the author. Maps 6.1, 6.2, and 7.1 were generated using Creative Commons Gabmap software. (John Nerbonne, Rinke Colen, Charlotte Gooskens, Peter Kleiweg, and Therese Leinonen (2011). Gabmap — A Web Application for Dialectology. Dialectologia Special Issue II.)

水族是中国少数民族之一,人口约430,000。水语属侗台语族的侗台语支。

我们在水族地区进行了一次比较全面的水语调查,此论文是这次水语调查的成果。这次调查的目的是

要记录水语各土语的语言资料并分析这些土语之间的系属关系和共时性关系。我们在16个研究点各收集了

约600个词条。我们也在各研究点采用了录音话语测试(即Recorded Text Test)来测试当地人对四种水语 土语的理解程度。

根据所收集到的数据和 Thurgood(1988)构拟的原始侗水语古音,并参考其他相近语言和其他的古 音构拟系统,我们首先阐述水语土语的历史演变。其次,我们对比土语之间的词汇相似度。再者,我们采 用莱文斯坦编辑距离(Levenshtein distance)算法比较各土语的语音相似度。最后,我们详细讨论通解度 测试的方法和结果。所收集到的词汇、各研究点的音系概述和话语录音测试的水英对照文本材料都包含在 本论文里。

研究结果显示,水语有四个主要的土语,而其中一个土语从历时性的角度属于侗语的分支。另外,有 三个土语之间的通解度较低。语言的系属关系并不能直接代表通解度的高低。

值得一看的内容包括:一、有数据显示原始侗水语是“一个半音节”(sesquisyllabic)语言(跟

Pittayaporn,2009,的观点一致);二、有数据显示水族地区有声调对转(余霭芹,1986)的扩散;以及

三、采用了新的“第二语言句子复述”通解度测试方法。

本论文是贵州人民出版社在2014年出版的 《水语调查研究》 的英文版。这本书的英文电子版是在贵

iv

Contents

Abstract Foreword

Acknowledgements Abbreviations

1 General Introduction

1.1 Introduction and objectives 1.2 Background

1.3 Previous research on the Sui language 1.4 Methodology

1.4.1 Site selection

1.4.2 Wordlist methodology

1.4.3 Intelligibility testing methodology 1.5 Research findings

2 Historical and Cultural Background

2.1 Origins of the Sui people and their migratory history 2.2 Geography of the Sui region

2.3 Information on the primary data points

2.3.1 Sandong (SD) (Shuigen village, Sandong district) 2.3.2 Zhonghe (ZH) (Hezhai hamlet, Zhonghe village) 2.3.3 Tangzhou (TZ) (Meiyu village, Tangzhou district) 2.3.4 Antang (AT) (Antang village, Tangzhou district) 2.3.5 Tingpai (TP) (Xinyang village, Tingpai township) 2.3.6 Dujiang (DJ) (Zenlei village, Dujiang township) 2.3.7 Banliang (BL) (Banliang village, Tangzhou district) 2.3.8 Jiaoli (JL) (Gaorong village, Jiaoli district)

2.3.9 Jiuqian (JQ) (Guchang village, Jiuqian township) 3 Historical Development of the Sui Dialects: Introduction

3.1 Background

3.2 Sui phonology sketch 3.2.1 The Sui syllable 3.2.2 Consonants 3.2.3 Vowels 3.2.4 Tones

3.3 Challenges to tracking sound changes in Sui 3.3.1 Proto-Sui: A questionable hypothesis

3.3.2 Lack of thorough and reliable reconstructions 3.3.3 Debate over prosodic form of the proto language 3.3.4 Difficulty in identifying cognates and loanwords 3.4 Data and conventions

4 Historical Development of Tones 4.1 Summary of argument

4.2 Background

4.3 Divergent tonal development in Sui dialects

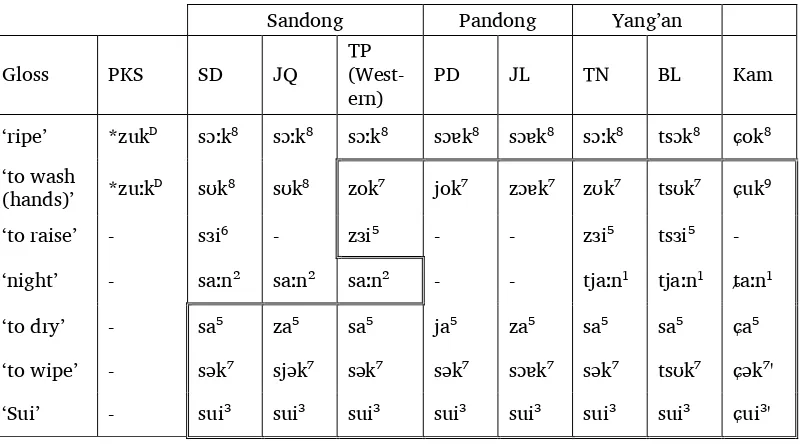

4.3.1 Shared tonal developments in Yang’an Sui and Kam

4.3.2 Shared tonal developments in Pandong, Western, Yang’an Sui and Kam 4.3.3 Unique tonal developments in Southern Sui

4.4 Tone splits and mergers

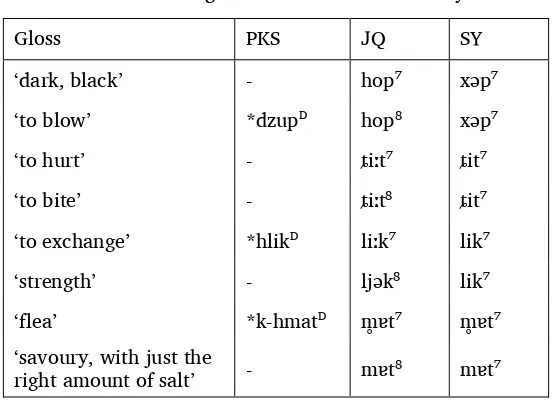

4.4.1 Merger of entering tones in Jiaoli (JL, Pandong) 4.4.2 Merger of Tones 7 and 8 in Shuiyao (SY, Southern) 4.5 Sui “voiced-high” tone value distinctiveness: An areal feature 4.6 Variation in Sui phonetic tone values

4.6.1 Tone 6 4.6.2 Tones 2 and 4 4.6.3 Tone 1 4.7 Summary of findings

5 Historical Development of Onsets and Rimes 5.1 Introduction

5.2 Onsets

5.2.1 Preglottalised onsets 5.2.2 Voiceless nasals

5.2.3 Prenasalised voiced stops 5.2.4 PKS *-w- clusters

5.2.5 PKS stop-lateral *ʔdl-, *kl-, *khl- clusters 5.2.6 Sibilants

5.2.7 Dorsals

5.3 From onsets to rimes: Palatalisation, labialisation and glides 5.3.1 Palatalised onsets

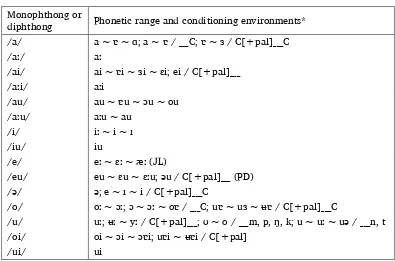

5.3.2 Labialised onsets 5.4 Rimes

5.4.1 PKS *-u 5.4.2 PKS *-i and *-e

5.4.3 PKS *-e and *-ai partial merger in Tangzhou (TZ)

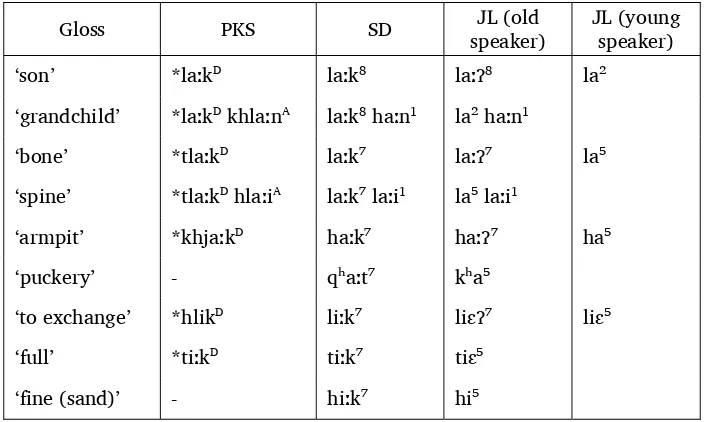

5.4.4 PKS *-iŋ, *-eŋ (loanwords) partial merger in Tangzhou (TZ) and Tingpai (TP) 5.4.5 PKS *-ik, *-ek, *-aːk mergers in Tangzhou (TZ), Tingpai (TP) and Jiaoli (JL) 5.4.6 PKS *-uk and *-uːk merger in Jiaoli (JL)

5.4.7 PKS *u and *uː before nasal codas

5.4.8 PKS *-i-, *-ə- and *-a- partial mergers conditioned by palatals 5.5 Phonetic variation

5.6 Shared diachronic innovations and Sui subgrouping 5.6.1 Yang’an

5.6.2 Southern

5.6.3 Central, Western, Eastern and Pandong 5.7 Cross-dialect similarities and “Sui-ness”

5.7.1 PKS retentions shared by all Sui dialects 5.7.2 Late sound changes shared by all Sui dialects 6 Lexical Similarity

6.1 Background 6.2 Methodology

6.2.1 Selection of data for comparison

6.2.2 Method of determining lexical similarity 6.3 Lexical similarity counts

6.3.1 Sui and Kam 6.3.2 Sui dialects 6.4 Sui dialectal variants

6.4.1 Pandong Sui dialect variants 6.4.2 Yang’an Sui dialect variants

6.4.3 Dialect variants shared by Pandong and Yang’an Sui 6.4.4 Southern Sui dialect variants

6.5 Semantic differences

6.5.1 Differences in semantic range

6.5.2 Semantic shift due to lexical replacement

6.5.3 Semantic differences due to differences in physical environment 6.5.4 SD and JQ: A lexical and semantic crossover region

6.5.5 Semantic change: Conclusion 6.6 Conclusion

7 Phonetic Distance 7.1 Introduction

7.2 Background: Dialectometry and Levenshtein distance (LD) 7.3 Methodology

7.3.1 Calculating Levenshtein distance

7.3.2 Selection of Sui and Kam data for comparison 7.3.3 Pre-processing of Sui and Kam data

7.4 Results of Sui dialect comparison

7.4.1 LD calculated using narrow, phonetic transcriptions 7.4.2 LD calculated using broad, phonemicised transcriptions

7.4.3 Sandong (SD) and Zhonghe (ZH): the most representative varieties 7.4.4 Cluster determinants

7.5 Results of Sui and Kam dialect comparison 7.6 Conclusions

8 Interdialect Intelligibility 8.1 Introduction

8.2 Measuring intelligibility

8.3 The history of intelligibility testing

8.3.1 Recorded Text Test (RTT): Story question and answer method 8.3.2 Word recognition tests

8.3.3 Sentence completion tests 8.3.4 Sentence translation tests

8.3.5 Content question and answer tests

8.3.6 Towards a new methodology: The sentence retelling (L2) test 8.4 Methodology

8.4.1 Designing the sentences

8.4.2 Translating and recording the sentences 8.4.3 Designing the tests

8.4.4 Test selection

8.4.5 Administering the tests (sampling and procedures) 8.4.6 Scoring the tests

8.5 Results

8.5.1 Intelligibility of Central Sui (GC) 8.5.2 Intelligibility of Southern Sui (SY) 8.5.3 Intelligibility of Yang’an Sui (LW) 8.5.4 Intelligibility of Pandong Sui (PD) 8.6 Conclusion

8.7 Methodology critique

9 Conclusions

9.1 Visualisations

9.2 Dialect clusters indicated by wordlist analysis 9.3 Dialect clusters indicated by intelligibility testing 9.4 Implications for language development

9.5 Final remarks

Appendix C: RTT questionnaire Appendix D: RTT sentences Appendix E: RTT core elements Appendix F: RTT result tables

Appendix G: Wordlist phonology sketches Appendix H: Wordlist data

viii

Foreword

In June 2010, my wife (Catherine Ching-yee) and I first visited Guizhou province to find out more about the minority peoples living there. Our objective was to identify a suitable and worthwhile minority language research project. Through introductions from the Vice Director of Guizhou University

Southwest Minorities Language and Culture Research Institute, Daisy Lai, we found ourselves in the Sui Research Institute of Sandu Sui Autonomous County, meeting Mr. Pan Xingwen, the head of the institute. He introduced us to the Sui people, accompanying us on a trip to a Sui village so that we could gain some first-hand insights into the Sui culture. Partly because of the Sui’s small population and their economic underdevelopment, very few experts have concentrated their efforts on Sui culture and language. On the other hand, Sui society is undergoing huge changes owing to modernisation and urbanisation. Thus research into Sui language and culture seemed to be both of great value and of great urgency.

In October of the same year, we arrived in Guizhou again, this time in the official capacity of researchers at Guizhou University’s Southwest Minorities Language and Culture Research Institute. We knuckled down to learning the Sui language. Learning a minority language is not easy in the best of circumstances. For us “old outsiders” hailing from foreign lands, it was doubly hard! The fact that the standard Sui dialect has not yet been promoted across the Sui region did not help us. As we tried to learn the language, we came across many different pronunciations, words and idioms. This gave us the idea of carrying out a dialect survey of the Sui language. In this way, we could make a comprehensive record of the distinctive accents, words and sayings that are used in different Sui regions. We hoped that this would be useful for present and future researchers of the Sui language.

The Sandu Sui Autonomous County Sui Research Institute was also extremely interested in conducting a survey because up until that point there had been little systematic documentation of the Sui dialects. Therefore, the Southwest Minorities Language and Culture Research Institute and the Sandu County Sui Research Institute joined forces to conduct the Sui Dialect Survey. This was the first formal cooperative project carried out by these two institutes. We were also incredibly fortunate to have two other scholars—Melissa Partida (née Woodrum) and Emily Wang Yongzhen (王永珍, Miao minority, from

Dafang county, Guizhou province)—enthusiastically join our research team. In Sandu county itself, the people who carried out most of the survey fieldwork were Lu Chun (陆春, Sui Research Institute),

Melissa Partida and Emily Wang (Southwest Minorities Language and Culture Research Institute). In Duyun, Dushan, Libo and Rongjiang counties, most of the fieldwork was conducted by Melissa Partida, Emily Wang and myself. This work is the fruit of this research. In total it took almost three years to complete. We hope that it will prove useful to all who are interested in Sui language and culture. Andy Castro

ix

Acknowledgements

We would especially like to thank the following Sui people who helped us to learn their language and provided support to the project: Pan Jintou (潘进头), Pan Simei (潘四妹), Pan Chenglong (潘承龙), Yao

Keqiang (姚克强), Yao Pinzhu (姚品柱), Yao Pincui (姚品翠) and Yao Helei (姚和磊). Without their

help, this project would not have been possible. I cannot emphasise enough the invaluable assistance of Pan Jintou, a Sui language extraordinaire who helped us to truly appreciate the richness and colour of the beautiful Sui language. He provided us with an enormous amount of source material that was crucial to the designing and implementation of the survey. We would also like to thank the villagers of Shuiyao village (水尧村), Shuiyao district in Libo county. Their hospitality and friendly assistance whilst we lived

in their village for two months in 2011 will forever be etched in our memories.

Additionally, the following people and institutions provided important logistical support for the survey fieldwork: Wang Bingjiang (王炳江), Wang Bingzhen (王炳真), Long Weiping

(龙伟平), the Guizhou Provincial Foreign Affairs Office, the Guizhou Provincial Minority Affairs

Commission, the Rongjiang County Minority and Religious Affairs Bureau, and the Libo County Sui Studies Association. We are extremely grateful for all their efforts.

We would like to express heartfelt thanks to all those who provided survey data, including Yao Jiongfeng (姚炯峰), Meng Yugan (蒙玉敢), Pan Chenglong (潘承龙), and the villagers from each of the

data points we visited (names are given in appendix G). We are indebted to Professor James N. Stanford and Dr. Cathryn Yang, who provided invaluable feedback on the analysis and write-up, and to Professor Shi Lin (石林), who supplied a large amount of Kam data for comparative analysis.

Of course, this kind of large-scale research is impossible without funding, so we would like to thank SIL East Asia Group and their supporters, especially the friends of Eric Ding, who assisted in this regard.

Fieldwork researchers and facilitators, and compilers and editors of this work include the following people:

Sandu Sui Research Institute:

Pan Xingwen (潘兴文), Lu Chun (陆春), Wei Shifang (韦世方), Shi Guomeng (石国勐)

Guizhou University Southwest Minorities Language and Culture Research Institute: Wang Liangfan (王良范), Melissa Partida (吴蜜香), Emily Wang (王永珍)

Qiannan Prefecture Teacher’s College Minorities Research Institute: Meng Yaoyuan (蒙耀远)

Guizhou Province Sui Studies Association:

Pan Tianhua (潘天华), Wei Zhangbing (韦章炳)

Libo County Sui Studies Association:

Meng Xilin (蒙熙林), Pan Yonghui (潘永会)

Jiarong Township Government: Pan Yongli (潘永利)

SIL, East Asia Group:

Dr. Cathryn Yang (范秀琳), Dr. Keith Slater (史继威)

In this work, we have used several pieces of specialist software for organising, analysing and presenting our data. Specifically: 1) “Speech Analyzer 3.1” (SIL International), for phonetic analysis and for producing the tonal pitch plots in appendix G; 2) “Phonology Assistant 3.3.5” (SIL International), for conducting phonological analysis; 3) “Fieldworks Language Explorer (FLEx) 7.2.7” (SIL International), for organising the RTT texts and producing the interlinearisations in appendix D; 4) “WordSurv 7.0” (Taylor University, White and Colgan 2012), for conducting the lexical analysis reported in chapter 6; 5) “Gabmap” (University of Groningen, Nerbonne et al., 2011), for carrying out the Levenshtein distance analysis and producing the maps and dendrograms in chapters 6 and 7; and 6) “GIMP 2.6” (Kimball et al., 2011), for producing and editing most of the maps and figures in this work. We would also like to thank David Olson and Ken Zook of SIL International, who made modifications to Phonology Assistant and FLEx so that they could better handle data in Sui and Chinese.

Andy and Catherine Ching-yee Castro

x

Abbreviations

General abbreviations

EM Early Mandarin EMC Early Middle Chinese

IPA International Phonetic Alphabet L1 first language (mother-tongue) L2 second language

LD Levenshtein Distance LMC Late Middle Chinese MC Middle Chinese

MDS Multi-Dimensional Scaling

OC Old Chinese

PKS Proto-Kam-Sui PMY Proto-Miao-Yao

PS Proto-Sui

PT Proto-Tai

PTK Proto-Tai-Kadai RTT Recorded Text Test

WPGMA Weighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean Glossing abbreviations

1 first person 2 second person 3 third person AGT agent marker CAP capability, ability CLF classifier

DEM demonstrative EMP emphatic EX exclusive IMP imperative IN inclusive

NEG negation marker NOM nominalising prefix PART particle

PASS passive marker PERF perfective aspect

PL plural

POSS possessive

PROG progressive aspect Q question marker SG singular

Data point abbreviations (more details can be found in chapter 1)

AT Antang

BL Banliang

DJ Dujiang

GC Gucheng

JC Jichang

JL Jiaoli

JQ Jiuqian

JR Jiarong

LW Lawai

PD Pandong

RL Renli

SD Sandong

SJ Sanjiang

SL Shuili

SQ Shuiqing

SW Shuiwei

SY Shuiyao

TD Tongdao

TN Tangnian

TP Tingpai

TZ Tangzhou

YC Yangchang

YK Yongkang

ZH Zhonghe

Reference work abbreviations

(See References for full details)

GMAC Guizhou Minority Affairs Commission

GZARMLC Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Minority Languages Commission ILCRD Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development

SCAEG Sandong County Almanac Editorial Group SDB Shuiyu Diaocha Baogao

1

1 General Introduction

(Andy Castro)

1.1 Introduction and objectives

The Sui Dialect Survey was a cooperative project conducted by researchers from the Southwestern Minorities Languages and Culture Research Institute (Guizhou University) and the Sui Research Institute of Sandu Sui Autonomous County, Qiannan Bouyei Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou Province in the second half of 2011. It was carried out with the approval and assistance of the Guizhou Minorities Affairs Commission and the Guizhou Department of Education. Further data was collected by researchers from the Southwestern Minorities Languages and Culture Research Institute in cooperation with partners in Duyun city, Dushan county, Libo county (all in Qiannan prefecture) and Rongjiang county

(Qiandongnan Dong Miao Autonomous Prefecture). These partners included the Minorities Research Institute of Qiannan Normal College, Duyun municipality, the Sui Studies Association of Libo county and the Minority Affairs Bureau of Rongjiang county.

The objective of the survey was to document a geographically wide-ranging and linguistically representative sample of Sui dialects and to elucidate the linguistic relationship between them. Although previous research has been carried out to this end, most notably a large-scale dialect survey conducted in 1956 (SDB 1958), neither a thorough set of comparative Sui dialect data nor a comprehensive analysis of Sui dialectal differences has ever been published. The current dialect survey aims to fill this gap.

In order to provide a context for the survey, the history of the Sui peoples and a historical and cultural introduction to each of the survey data points are given in chapter 2.

The remainder of the work is devoted to presenting the findings of the survey. There were two main elements to the survey fieldwork: 1) collecting wordlists; and 2) conducting intelligibility tests in

Recorded Text Test (RTT) format, using a sentence retelling method. By means of these two activities we hoped to gain an overall picture of the Sui dialect situation. Various types of analysis were applied to the wordlist data: 1) comparison of diachronic sound changes, the most widely accepted basis for

subgrouping languages and dialects (Campbell 2004, Huang Xing 2007), presented in chapters 3, 4 and 5; 2) lexical comparisons (chapter 6); and 3) phonetic distance calculations (chapter 7). The

methodology and results of the intelligibility testing are presented in chapter 8. An overall summary of the survey results along with conclusions and areas for further research are given in chapter 9. Finally, the raw data which we collected on the survey can be found in the Appendices.

1.2 Background

Sui is typically classified as belonging to the Kam-Sui branch of Tai-Kadai (Diller 2008a, James Wei 2011, Lewis et al., 2013). One of the greatest linguists of the last century, Li Fang-kuei, first coined the term “Kam-Sui”, including within this branch Sui, Maonan (Sui’s closest relative), Kam, Mulam, Mak and Then (Li Fang-kuei 1943, 1948). Sui occupies an important position in Tai-Kadai comparative research due to its relatively conservative nature, particularly in terms of its rich inventory of sounds, many of which have been lost in other Tai-Kadai languages (James Wei 2008).

There are various hypotheses regarding the relationship of Tai-Kadai to other language families in East and Southeast Asia. Chinese scholars typically advocate the positioning of Tai-Kadai within the Sino-Tibetan language family (Luo 2008, James Wei 2011). Western scholarship generally holds that Tai-Kadai is an independent language family not genetically related to, although heavily influenced by, Sino-Tibetan. Another theory, originally proposed by Benedict (1975), holds that there is a genetic

relationship between Tai-Kadai and Austronesian—the “Austro-Tai” hypothesis. This theory has been gaining wider credence in recent years.

phonological and lexical similarity. SDB (1958) further divided Sandong dialect into two sub-dialects: 1) Rongjiang county; and 2) the rest. Castro (2011) proposed a slightly different alignment, with Sandong dialect comprising two other sub-dialects: 1) Southern Sui (Libo county and south-eastern Sandu county); and 2) Central Sui (the rest), as shown in map 1.2. He noted that the geographical delineation between the Southern and Central Sui dialect groups coincides with the division between those Sui who celebrate the Mao festival (in the south) and those who celebrate the Dwa festival (further north). The results of the current survey support both SDB’s and Castro’s propositions, as well as elucidating the relationships between the other Sui dialects.

Map 1.1. Traditional grouping of Sui dialects.

Map drawn by the author, based on locations given Map 1.2. Castro’s (2011) grouping of in Zhang Junru 1980, showing Sandu, Libo and Sui dialects

Rongjiang county towns and borders. Also showing “Rongjiang” sub-dialect (SDB 1958)

In this work we refer broadly to three Sui dialects: Sandong; Pandong; and Yang’an. We further subdivide Sandong into four “subdialects”: Central (including the Sandong standard and also embracing Zhonghe and Zhouqin townships); Western (a large area of the Sui heartland including Tingpai,

Map 1.3. Sui dialects and subdialects referred to in this work

Central Sui as spoken in Sandong district, Sandu county, is considered the “standard dialect” (Zhang Junru 1980, James Wei 2011). Central, Western and Southern Sui have a rich inventory of over 60 initials (including bilabial, alveolar, palatal, velar and uvular consonants and preglottalised,

prenasalised, palatalised and labialised obstruents) and over 50 finals (including nasal and -p, -t, -k

codas).1 We provide a phonology sketch of Sandong dialect in chapter 3.

Pandong and Yang’an dialects and the Eastern subdialect of Sandong have smaller phonemic inventories. They generally have fewer preglottalised initials, fewer voiceless nasals and fewer

prenasalised stops. Sui has six contrastive tones on unchecked (or “live”) syllables (i.e., open syllables or syllables closed by a sonorant) and two on checked (or “dead”) syllables (i.e., syllables closed by a stop) with different pitch contours depending on the length of the vowel nucleus.

1.3 Previous research on the Sui language

A significant amount of descriptive work on Sui has been published to date, although a lot of work remains to be done. The earliest documentation of the Sui language was made by the renowned Tai-Kadai linguist Li Fang-kuei. In 1942 Li spent some time in “Ngam” and “Li” villages (known in Chinese as Shuili and Shuiyan, in Libo county) and he later published several annotated Sui texts which he gathered there (Li Fang-kuei 1977b). He collected a vast amount of Sui vocabulary which was published posthumously in the form of a “Sui-Chinese-English glossary” (Li Fang-kuei 2008), along with some vocabulary that he collected from “Pyo” village (then Shuipo township, Libo county, now Hengfeng township in Sandu county) and Rongjiang county. His observations of Sui initials and tone (Li Fang-kuei 1948) played a crucial role in his reconstruction of Proto-Tai-Kadai (Li Fang-kuei 1977a), the first

published reconstruction in this language family. Li was also the first to describe Mak and to delineate the Kam-Sui branch of Tai-Kadai (Li Fang-kuei 1943).

In addition to Li’s glossary (which, being based on Li-Ngam, largely reflects Southern Sui pronunciation and lexicon), two other Sui glossaries or “dictionaries” have been published. The most comprehensive to date, entitled “Chinese-Sui dictionary”, was collated by Zeng Xiaoyu and Yao Fuxiang (Zeng and Yao 1996). Although it is primarily based on standard Sui as spoken in Sandong township, it is heavily influenced by Yao’s own dialect, that of Shuilao village in present-day Shuiyao township, Libo county, a variety of Southern Sui. In collaboration with Mahidol University, James Wei and Jerold Edmondson published a quadrilingual “Sui-Chinese-Thai-English dictionary” (Burusphat et al., 2003). This is based on Wei’s own variety of Sandong dialect from Miaocao village, Dahe township, although it includes unmarked regional pronunciations too.2

The most comprehensive general description of the Sui language published to date is the “Sketch of the Sui language”, written by another well-known expert in Tai-Kadai languages, Zhang Junru (1980). This work includes a small section on Sui dialects focussing on the lexical and phonetic features of Pandong and Yang’an dialects. Other descriptions of Sui and its dialects can be found in Xia 1988, 1989, 1992, and James Wei 2008, 2011. No comprehensive, detailed analyses of Sui morphology, syntax or discourse have yet been published

In terms of historical comparative work in the Kam-Sui branch, the greatest contributions have been made by Li Fang-kuei (1948, 1977a), Thurgood (1988), Ferlus (1990, 1996) and Zeng (1994, 2004). These works, along with others, are discussed in more detail in chapters 3 to 5. Generally, a lack of good data for Sui, Kam, Mulam and Maonan has held back comparative work in this branch. Zeng (1994, 2004, 2010) has made significant contributions to understanding the historical relationship between Chinese and Sui. These two languages have been in extended contact over many centuries, if not millennia, and a good grasp of historical developments in the Sinitic branch is crucial for Sui

comparative work. For this, researchers can look to scholars such as Baxter, Sagart, Pulleyblank, Li Fang-kuei, Wang Li, Zhengzhang Shangfang and Pan Wuyun.

Dialectology is a small but growing field of linguistics. A key reference work for understanding the history of this field is Chambers and Trudgill’s Dialectology (1998). In the specific subfield of

dialectometry, Nerbonne (2000) and Gooskens (2006, 2007, 2013) and their team at the University of Groningen have made valuable contributions, in particular regarding the use of the Levenshtein distance algorithm (Levenshtein 1965) to compute phonetic similarity between dialects. Tang and van Heuven (2007, 2009, 2011) developed an innovative method for testing functional intelligibility, correlating their results with more traditional phonemic comparisons. These discoveries, along with related dialectometric research, are discussed in more detail in chapter 8.

The greatest contributions to understanding Sui dialectology specifically have been made by James Stanford (2007, 2008a, 2008b, 2009, 2011). Stanford has made significant inroads into uncovering the relationship between clan identity and dialectal speech patterns. His work has partly been informed by the unpublished results of a “Sui Dialect Survey” carried out in the 1950s (SDB 1958), the only

manuscript to describe Sui dialect differences in detail. Castro (2011) was the first to posit a “Southern Sui” dialect based on a historical comparison as well as on lexical and cultural factors. Nevertheless, a sweeping, comprehensive picture of the overall Sui dialect situation has never been published. This work seeks to address this deficiency.

Descriptions of Sui culture and publications of traditional Sui songs and shamanic books (using Lee Sui character script) are too numerous to list here. Probably the most comprehensive description of Sui history and culture that has been published was written by the eminent Sui scholar Pan Chaolin, along with Wei Zonglin (2004). In addition to Pan’s work, Wang Pinkui and Mo Junqing (1981) and Liang Min (2008) have made contributions to understanding the migratory history of the Sui people. Sagart et al., (2005) and Liang and Zhang (1996, 2006) are good starting points for learning about the various theories regarding the Tai-Kadai peoples and the peopling of Southeast Asia. Wei Shifang (2007), Lu

Chun (2010) and Kamil Burkiewicz (2012) have all produced glossaries of Lee Sui characters, the latter being the first to include English explanations.

1.4 Methodology

1.4.1 Site selection

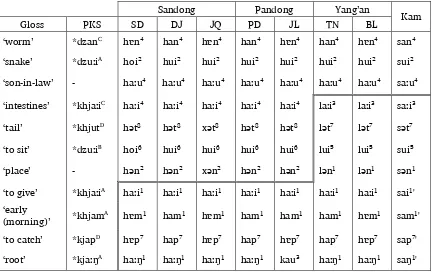

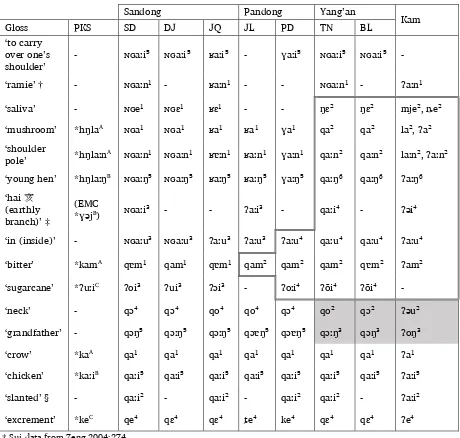

We collected wordlist data from nine locations in Sandu county, the ethnic and cultural heartland of the Sui people and the sole Sui Autonomous County in China. These were our primary data points. We picked data points that would represent the various Sui dialects and accents as completely as possible. Background research and local knowledge were used to inform our data point selection. In total, seven data points were chosen to represent Sandong dialect (two to represent Central, three to represent Western, and one each for Southern and Eastern subdialects), one to represent Yang’an dialect and one to represent Pandong dialect. Data point locations, including abbreviations by which we refer to them throughout this work and Sui loconyms (region hən² and village ʔbaːn³) are listed in table 1.1.

Table 1.1. Wordlist collection sites in Sandu county Ref Sui region (village) Location (Chinese) Dialect area Researchers

SD toŋ⁶(qan²) Shuigen, Sandong district (

三洞乡水根村)

Sandong (Central)

Wei Shifang, Lu Chun, Andy Castro, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen

ZH tsjəŋ²

(ʔnja¹) Hezhai, Zhonghe district (中和镇中和村和寨)

Sandong (Central)

Lu Chun, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen

TZ pʰaːn¹(jiu²) Meiyu, Tangzhou district (

塘州乡枚育村)

Sandong (Western)

Lu Chun, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen

TP ɕian⁵(ɕian⁵) Xinyang, Tingpai district (

廷牌镇新仰村)

Sandong (Western)

Lu Chun, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen

Lu Chun, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen

DJ ŋa²(tsə⁰ noi²) Zenlei, Dujiang district (

都江镇怎累村上村)

Sandong

(Eastern) Wei Shifang, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen JQ mui⁶(ʔdaːn¹) Guchang, Jiuqian district (

九阡镇姑偿村)

Sandong (Southern)

Lu Chun, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen

BL pə⁰ ljaːŋ²(pə⁰ ljaːŋ²)

Banliang, Tangzhou district

(塘州乡板良村)

Yang’an Lu Chun, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen

JL qau⁴ nam³(qau⁴ nam³)

Gaorong, Jiaoli district (交梨乡高戎村)

Pandong Lu Chun, Melissa Partida, Wang Yongzhen

Table 1.2. Wordlist collection sites outside Sandu county

Pandong, Yanghe district, Duyun City (都匀市阳和水族乡潘洞村)

Tangnian, Tanglian village, Benzhai district, Dushan county

JR ljaŋ¹(la⁶ ljaŋ¹) Laliang, Jiarong district, Libo county (

荔波县佳荣镇拉亮村)

Dangmin, Renli district, Rongjiang county

Guyi, Sanjiang district, Rongjiang county

SW vai⁶(vai⁶) Shuiwei, Rongjiang county (

榕江县水尾水族乡水尾村) With regard to intelligibility testing (RTT), we tested four varieties of Sui, one each for Central, Southern, Pandong and Yang’an. We refer to these four varieties as our “reference dialects”. We did not test Eastern Sui because we already knew from Castro’s (2011) study that Southern Sui was likely to be far more distinctive (from Central) than Eastern, and so it turned out to be. The RTT text providers are listed in table 1.3 along with their home town locations, the abbreviations used to refer to these locations in this work, and the dialect that each of them represents. We chose Shuiyao to represent Southern Sui because we already had anecdotal evidence indicating that there are significant

Table 1.3. RTT text providers

Sui speaker Location ref Sui region Location (Chinese) Dialect

Wei Shifang

韦世方

GC toŋ⁶

Gucheng, Sandong district, Sandu county

(三都县三洞乡古城村)

Sandong (Central) Yao Jiongfeng

姚炯峰

SY ʔjaːŋ¹ Poding, Shuiyao district, Libo county (

荔波县水尧水族乡水尧村坡顶)

Sandong (Southern) Meng Yaoyuan

蒙耀远

PD tʰaːu¹ Pandong, Yanghe district, Duyun city (

都匀市阳和水族乡潘洞村)

Pandong Meng Yugan

蒙玉敢

LW jaːŋ² Lawai, Tingpai district, Sandu county (

三都县廷牌镇拉外村)

Yang’an

For our wordlist analysis, we supplemented data gathered during this survey with data which has already been published, in particular Li Fang-kuei (1965, 2008), and Zeng (1994, 2004), as well as from an unpubliushed manuscript, SDB (1958). Details of these extra data sources, along with the

abbreviations by which they are denoted in this work, are given in table 1.4. Then map 1.4 shows the locations of our wordlist collection sites in addition to these supplementary data points. On occasion we also refer to data supplied by Zhang Junru (1980), Zeng and Yao (1996), Zeng (2010), Stanford (2011) and James Wei (2011).

Table 1.4. Key supplementary data considered in this work

Ref Location (Chinese) Dialect area Source

JC Jichang district, Duyun City (

都匀市基场水族乡)

Pandong

Zeng (1994, 2004) YC Yangchang, Benzhai district, Dushan county (

独山县本寨水族乡羊场村)

Yang’an

SQ

Shuiqing (Shuilao, Shuiyao district, Libo county)

(水庆,即荔波县水尧水族乡水捞村)

Sandong (Southern)

YK Yongkang district, Libo county (

荔波县永康水族乡)

Sandong (Southern) SL Shuili district, Libo county (“Li” and “Ngam”) (

荔波县水利水族乡)

Sandong

(Southern) Li Fang-kuei (1965, 2008) TP Tingpai district, Sandu county (“Pyo”) (

三都水族自治县廷牌镇)

Sandong (Western)

TD Tongdao, Renli township, Rongjiang county (

榕江县仁里乡通倒村)

Map 1.4. Locations of data points referred to in this work. Central, Western, Eastern and Southern all belong to the traditional Sandong dialect designation

The dashed line is the Guizhou-Guangxi border. Spots are wordlist collection sites, triangles are RTT text sites, stars are data points from Zeng (1994, 2004), squares are data points from other sources.

1.4.2 Wordlist methodology

1.4.2.1 Wordlist design

Our wordlist had a total of 610 lexical items. We aimed to include examples of as many different onset and rime combinations as we could find in previous literature, relying heavily on Sandu County

Education Bureau and Sandu Sui Research Institute (2007). We referred extensively to Thurgood (1988) to make certain that we had words which contained all reconstructed Proto-Kam-Sui sounds. We also included the Swadesh 100 and most of the Swadesh 207 core lexical items (Swadesh 1952) in order to ensure a wide range of semantic domains.3

1.4.2.2 Sampling of wordlist consultants

We were already aware that the Sui language is in a state of flux and that accents and dialects are changing in some Sui areas. For example in Shuiyao (SY), young people have largely replaced ⁿd- with

l-in words such as ‘to see’ ⁿdo³ (> lo³) and ᵐb- with v- in words such as ‘male’ ᵐbaːn¹ (> vaːn¹). In an attempt to document sound changes such as these which are currently underway, we decided to elicit the full wordlist from three speakers at each data point: one speaker over 60 years old; one speaker between 35 and 45 years old; and one speaker under 20 years old.

The key requirement for wordlist consultants was that they must have been born and raised in the village in which we collected the data. We also tried to ensure that all consultants had the same

surname, since Stanford (2007, 2009) argues persuasively that dialect distinctives in Sui are not entirely differentiated on a geographical basis but are also linked to the clan (thus he refers to “clan-lects”).

Most of our consultants were male, but occasionally we chose an unmarried female as the youngest consultant. Females who had married into the village were excluded because Stanford (2009) has shown that married women generally persist in holding on to their own region’s speech distinctives rather than adapting their speech to the village and clan into which they have married. Stanford (2008b, 2009) has also shown that Sui people consistently speak their “patrilect” (father’s dialect) as a subconscious act of “clan loyalty”. We therefore deemed it unnecessary to impose a restriction in terms of the birthplace of the consultants’ mothers.4

1.4.2.3 Wordlist elicitation and recording

The wordlists were elicited from all language consultants simultaneously in multiple sessions. We encouraged each consultant to say the word exactly as they usually say it and tried to prevent them from mimicking the other consultants.

At each data point we first elicited twenty words to provide an overview of the tonal system— two words for each of the six tone categories on unchecked syllables plus four words for each of the two tone categories on checked syllables (including short and long vowel variants). Words in the rest of the wordlist were then regularly compared with these twenty words to ensure that the tones were transcribed accurately.

Prompts were usually in Chinese. Phrases were often included in the prompt to ensure that we elicited words which were semantically equivalent, for example: item 60 ‘grass (wild grass which grows on the mountain)’; item 201 ‘spoon (for drinking soup)’; and item 318 ‘to come out (e.g., a chicken coming out of an egg)’. For some items we showed pictures, again in an attempt to ensure semantic equivalence. These items were ‘cypress’, ‘fir’, ‘maple’, ‘kiwi fruit’, ‘millet’, ‘bean pod’, ‘otter’, ‘pangolin’, ‘porcupine’, ‘Crucian carp’, ‘locust’, ‘cricket’, ‘grasshopper’, ‘stink bug’, ‘pancreas’, ‘hoe’, ‘longbow’, ‘crossbow’, ‘arrow’, ‘yoke (for oxen)’, ‘top (game)’, ‘bamboo hat’, ‘raft’ and ‘hunchback’.

During the elicitation sessions, we checked each word elicited against Proto-Kam-Sui and words elicited in other locations. We double-checked the precise meaning and usage of any words which appeared to be non-cognate. We also probed for cognate words to ascertain whether any semantic shift had occurred. Occasionally, consultants gave us words which they said were not used in their village but which they had heard spoken by people from other villages. We did not record these words. All other variants provided for each gloss were transcribed and recorded along with notes pertaining to their meaning and usage.

We elicited and transcribed the wordlists in several sessions, usually fifty to one hundred words per session. After each elicitation session we recorded the words for that session individually from each consultant, thus preventing a “mimicking” effect.5 Due to time limitations, we recorded all items in isolation only (in three repeated utterances) and did not record them in sentence frames. Items were recorded in uncompressed, digital WAV format (24-bit PCM with a sample rate of 144.1kbps) on a Roland Edirol R09-HR using a hand-held Sony ECM MS907 condenser microphone.

4Although very young Sui children sometimes speak with the dialect distinctives of their mothers, by the age of around ten most of these distinctives have been lost and children speak their patrilect almost exclusively (Stanford, 2008b:582, 591).

1.4.2.4 Wordlist analysis

There are two main approaches to using wordlist data for determining the taxonomy of languages and dialects. The first is a historical comparative approach which aims to uncover the genetic relatedness of different language varieties. It is usually conducted in order to understand how different languages relate to each other genetically (i.e., how languages have evolved over time) and thereby to classify languages and language families. Application of the comparative method often results in tree diagrams of the type we give in chapter 5, figure 5.1, for the taxonomy of Kam-Sui. The second approach is that of

“dialectometry”. This approach aims to examine the synchronic similarity of different language varieties, often with the aim of delineating dialect boundaries within a single established “language”. Thus the first, historical, approach is often used to classify “languages”, whereas the second, dialectometric, approach is often used to classify “dialects”. Of course there is overlap between the two approaches, especially in cases where the definition of different varieties as “languages” or “dialects” is unclear. Although Sui is universally considered to be one “language”, we make use of both approaches in this work.6

In chapters 3 to 5, we apply the comparative method to our data with some measure of success. Because of the shallow time depth, we pay close attention to outside evidence such as migratory history in order to uncover the timing of different sound changes and thereby to distinguish between inherited sound changes and sound changes which have diffused across a geographical region more recently.

In chapters 6 and 7 we analyse our wordlist data from a more synchronic perspective. In chapter 6 we calculate lexical similarity on the basis of shared historical cognates. In chapter 7 we examine

phonetic similarity by applying the Levenshtein distance algorithm, a dialectometric approach which has been shown to have a strong, significant correlation with both intelligibility and speakers’ perceived distances between varieties (Gooskens 2006, Yang Zhenjiang 2009).

We feel that for a complete understanding of the dialect situation, both historical and dialectometric analyses are necessary. Both can inform language development decisions and assist in the process of developing mother-tongue materials to suit the needs of all Sui speakers.

1.4.3 Intelligibility testing methodology

For testing inter-dialect intelligibility, we used a type of Recorded Text Test (RTT) involving the

“retelling” or “translation” of long sentences recorded in the four reference dialects (locations for which are given in 1.4.1 above). Due to the specific test design, we were able to test only three out of the four reference dialects at each data point. We tested a set of 42 sentences, fourteen sentences for each of three reference dialects, on nine participants, rotating the sentences between them based on a “Latin square” design (Box et al., 1978). Thus, whilst each participant only heard fourteen sentences from each reference dialect, overall all 42 sentences in all three dialects were tested at each location. The background to the RTT development and design, along with detailed descriptions of the testing and sampling methods employed during this survey, are provided in chapter 8.

1.5 Research findings

Our analysis shows that, from a synchronic perspective, the traditional grouping of Sui into three dialects, viz. Sandong, Pandong and Yang’an, is justified. Sandong may further be divided into four subdialects: Central (Sandong, Zhonghe and Zhouqin townships); Western (Shuilong, Dahe, Tingpai, Tangzhou and Hengfeng townships); Eastern (Dujiang and Bajie townships in Sandu county and Sanjiang and Renli townships in Rongjiang county); and Southern (Jiuqian and Yanggong townships in Sandu county, Shuili, Shuiyao, Jiarong and Yongkang townships in Libo county and Shuiwei township in

6Currently, increasingly more historical linguists are using quantitative analysis for uncovering phylogenetic relationships, see for example the work of Paul Heggarty

Rongjiang county). Within Sandong, the Central and Western subdialects are linguistically extremely close to each other, Eastern is slightly more distant, and Southern is the most distinctive.

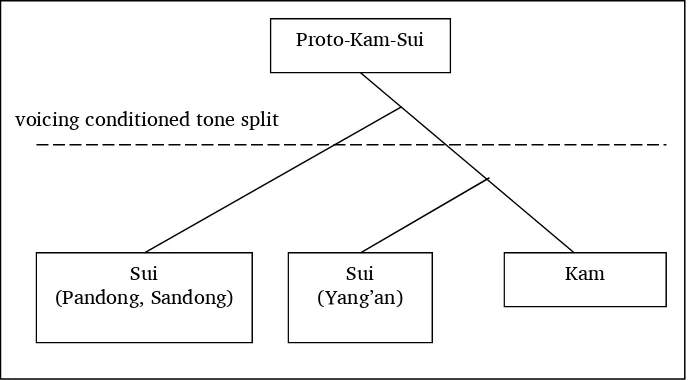

From a historical perspective, the evidence suggests that Yang’an actually belongs to the Kam branch of Kam-Sui, although some recent sound changes and lexical borrowings mean that it now resembles Sui in some respects. Within the Sui branch, the Southern varieties branched off early on and are extremely distinctive. Pandong dialect appears to be a sister dialect to Western Sui, while Eastern Sui lects appear to have branched off from Central Sui much more recently.

It is worth noting that our historical comparative analysis with respect to Yang’an and Southern clusters is backed up by external cultural and geographical evidence. For example, the Yang’an Sui call themselves sui³ kam¹, which literally means “Kam-like Sui”, and they celebrate Chinese New Year (in common with the Kam peoples) rather than the Sui’s own Dwa New Year. Southern Sui speakers celebrate the Mao festival instead of Dwa. From a geographical perspective, most of the Southern Sui area is situated around the upper tributaries of the Longjiang river, whereas all other Sui areas are served by the upper reaches and tributaries of the Duliujiang river. More research into the migratory history of the Kam and Sui peoples may help to explain our historical comparative findings further.

12

2 Historical and Cultural Background

(Pan Xingwen, Wei Shifang, Lu Chun, Shi Guomeng)

2.1 Origins of the Sui people and their migratory history

According to Li Pingfan and Yan (2011:435ff.), the Sui ancestors originated in the Luogushui (骆谷水)

region of Shaanxi province, living in the Sui River (睢水) basin.1 They migrated south and became one of

the Baiyue ethnic groups.2 It was not until the Tang dynasty that the character Shui

水 began to be used

in Chinese history books to refer to the ethnic group.3

After the capitulation of the Yin and Shang dynasties, the Sui ancestors migrated south across Hubei and Hunan, arriving in the Guangxi region and assimilating into the Baiyue ethnic groups of ancient southern China. After the unification of China by the Qin, the imperial government sent troops to attack the southern regions. The Sui ancestors then migrated upstream, northwards, in what became the second great migration in their history. They finally settled in the upper reaches of the Longjiang and Duliujiang rivers in the border regions of present-day Guangxi and Guizhou. Gradually they acquired the identity of a single ethnic group, developing from a branch of the “Luo Yue (骆越)”, a group which came from the

Baiyue (SCAEG 2007:9).

The Sui autonym comes from the Sui river which provided sustenance for the Sui ancestors. The first volume of Treatise on Rivers and Canals of the Ming History《明史•河渠志上》says, “Water from the

Yellow River is directed into the Bian (汴) river, the Bian into the Sui (睢), the Sui into the Si (泗), the

Si into the Huai (淮), and thence into the sea.” Historically, the Sui and other non-Han ethnic groups

were referred to collectively as “Baiyue”, “Liao (僚)”, “Miao (苗)” or “Man (蛮)”, among others. During

the Tang dynasty, Fushui prefecture (抚水州) was created in the Sui region. Crimson Elegance《赤雅》,

written by the famous Ming poet Kuang Lu, records that “the Shui (水) people are a type of Liao (僚)”.4

After the middle of the Qing dynasty, the Sui began to be known as “Shuijia Miao (水家苗)” (literally

“Miao from the Shui clan”) or “Shuijia (水家)” (the “Shui clan”). Post-liberation, after consulting the Sui

people themselves, the State Council officially designated them “Shuizu (水族) (Shui Minority)” (SCAEG

2007).

2.2 Geography of the Sui region

The Sui live primarily in the south of China, in the border regions of Hunan province, Guizhou province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. They live on the edge of the Miao Ling mountain chain (苗岭 山脉) on the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, mostly in the areas surrounding Moon Mountain (Yueliang Shan 月亮山). The terrain is rugged, as the mountains transition to foothills. It is a beautiful area of dense

forests with poor transportation links. Because of this, Sui customs have been preserved very well. The majority of the Sui people live in Qiannan and Qiandongnan prefectures of Guizhou province. Small numbers of Sui also live in Guangxi and Yunnan, as well as in major cities such as Guiyang, Beijing, Shanghai, Kunming and Nanning. At the end of 2011, there were around 430,000 ethnic Sui in the whole of China. Around 240,000 of these were living in Sandu Sui Autonomous County (Sandu County Statistics Bureau 2012).

1This claim is partly based on the fact that the Mandarin pronunciation of the character

睢 (or 濉) Sui [swɛi⁵⁵], is very similar to the Sui’s own autonym, [sui³³] (Pan and Wei, 2004). See Liang (2008) and chapter 5, section 5.2.6.5 of this work for an alternative view.

2The Chinese term “Baiyue

百越” (literally ‘Myriad Yue’), refers to the ethnic groups who lived in southern China in ancient times.

Sandu is the only Sui autonomous county in China. It is situated in the southeast of Qiannan Bouyei-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Guizhou Province, between Moon Mountain and Thunder God Mountain (Lei Gong Shan雷公山), spanning the area from 107°40'E to 108°14'E and 25°30'N to 26°10'N. Sandu

county is 56 km east-west at its widest point and 73 km north-south at its longest point. Over 50% of the total Sui population in China live in Sandu county. Sandu has a total area of around 2,400 km2. There are 21 districts and townships, and 242 administrative villages.5 At the end of 2011, ethnic minority people accounted for 96.9% of the total population of Sandu. The Sui accounted for 65.8% of the total population of Sandu county (Sandu County Statistics Bureau 2012). Sandu is informally known as “the place whose beauty is like the feathers of the phoenix”.

The Sui minority live in the following places:

• Sandong, Zhouqin, Jiuqian, Yanggong, Hengfeng, Tingpai, Tangzhou, Shuilong, Zhonghe, Sanhe, Lalan, Dayu, Yangfu, Wubu, Bajie, Dujiang, Jiaoli, Pu’an, Fengle, Dahe and Hejiang, 21 districts and townships in Sandu county, Guizhou province;

• Jiarong, Shuiyao, Yongkang and Shuili districts and townships in Libo county, Guizhou province;

• Benzhai, Jiading, Wengtai and Shuiyan districts and townships in Dushan county, Guizhou province;

• Jichang, Fenghe and Yanghe districts in Duyun municipality, Guizhou province;

• Fuquan city and Huishui county in Guizhou province;

• Shuiwei, Xinghua, Dingwei, Sanjiang and Renli districts and Tashi Yao Sui minority district in Rongjiang county, Guizhou province;

• Longquan township, Yangwu district and Yahui district in Danzhai county, Guizhou province;

• Yongle township and Dadi Sui township in Leishan county, Guizhou province;

• Congjiang and Jianhe counties in Guizhou province;

• Huanjiang and Rongshui counties in the north of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region;

• and Gugan Sui district, Fuyuan county in Yunnan province.

2.3 Information on the primary data points

2.3.1 Sandong (SD) (Shuigen village, Sandong district)

Shuigen village is situated 2.5 km north of Sandong district People’s Government at the foot of General’s Slope (Jiangjun Po将军坡). The village is arranged in the shape of a crescent moon and is 3.1 km

2 in area. Shuigen is the location of the administrative village office, in Shuigen Great Hamlet. The administrative village oversees five village groups with a total population of 1,255 people comprising 238 households. The population of Shuigen are quite concentrated. Sui minority constitutes 99.5% of the village’s total population. The whole village has 1,000 mu of cultivated land.6 The primary source of income is agriculture, secondary sources include outsourced labour and trade. The cypress wood at the entrance of the village has thirteen steles engraved with Lee Sui character script.7 The village boasts paved roads, street lighting, good sanitation and other modern facilities.

5In China, an ‘administrative village’ is the term for a group of villages served by a single party committee. A ‘natural village’ refers to a single village. There are usually several natural villages within one administrative village. 6mu

亩 is a Chinese measure of area, equivalent to 0.0667 hectares. 7Lee Sui [lɛ¹ swi³] (shuishu

2.3.2 Zhonghe (ZH) (Hezhai hamlet, Zhonghe village)

Zhonghe is situated 27 km south of Sandu county seat and 0.5 km north of the Zhonghe township government. Zhonghe administrative village covers an area from 107°53'E to 107°69'E and 25°45'N to 25°50'N. The village committee buildings are at an elevation of 720m. The east borders Ladan village (拉 旦村), the south Guyin village (姑引村), the west Xiyang (西洋村) village and the north Pangzhai village

(庞寨村). Zhonghe administrative village has a population of 1,554 people constituting 213 households,

of which Sui minority account for 98.4%. The only people who are not ethnically Sui are government officials who belong to other minority groups. The village is surrounded by mountains with a long, narrow plain in the middle. Most of the cultivated land is in this plain. The village mainly produces rice, wheat, maize, soybeans and chilli peppers. Zhonghe village is at the centre of Zhonghe township and has a market which is held on the fourth (卯) and the tenth (酉) days according to the traditional calendar.

The trunk road from Sandu to Libo county travels through Zhonghe village. Zhonghe comprises four hamlets: Dazhai (大寨), Zhongzhai (中寨), Hezhai (和寨) and Zaodai (早歹).

2.3.3 Tangzhou (TZ) (Meiyu village, Tangzhou district)

Meiyu village is the location of the Tangzhou district People’s Government in Sandu Sui Autonomous County. It is situated 32 km from the county seat at an elevation of 865m, with a warm and humid climate. The administrative village covers a total area of 2.1 km2, overseeing four village groups and one residential group. The village office is in the lower village group of Meiyu. The total population of the village is 735 people constituting 162 households. 97.9% of the village population are Sui minority. There are 380 mu of cultivated land, an average of 0.28 mu per person. Forested mountain slopes account for most natural resources. There are about 1.1 mu of woodland per person and a total of 1,579 mu of wild grassland. Approximately 682 mu of uncultivated land has potential for cultivation. High quality resources that could be developed commercially include woodland, grassy slopes and ponds. 2.3.4 Antang (AT) (Antang village, Tangzhou district)

Antang village is situated 6 km north-west of Tangzhou district government. The road from Tangzhou district to Hejiang township 合江镇 runs through the village. The village has a total area of 2.5 km

2 with an average elevation of 730m. Antang administrative village oversees 17 village groups, comprising 471 households with a total of 2,200 people (2,189 agricultural and eleven non-agricultural).8 Of these, 2,005 are Sui minority. In the village there are 1,112 people of employable age, 122 children in senior high school, 266 in junior high school, and 854 in elementary school. There is a total of 2,021 mu of agricultural land, about 0.95 mu per person, of which 0.43 mu comprises fields or paddies. The main natural resource is forested mountain slopes, with an average of 1.84 mu of woodland per person. There are also 3,015 mu of wild grassland, of which 2,604 mu is cultivatable. In recent years, the village has undergone a significant amount of development. The local elementary school, which covers grades one to six, has 1,260m2 of buildings and 413 students. There is one public WC and one area for village activities which is 108m2. High quality resources that could be developed commercially include woodland, grassy slopes and caves.

2.3.5 Tingpai (TP) (Xinyang village, Tingpai township)

Xinyang village is one of the administrative villages of Tingpai township in Sandu Sui Autonomous County. It oversees 15 village groups, comprising 632 households and a total population of 3,337 (agricultural population: 3,006; non-agricultural population: 331); 98.9% of the population are Sui minority. The village offices are situated at Xinyang Elementary School. The village has a total area of

6.09 km2, with 2,439 mu of cultivated land, comprising 2,054 mu of rice paddies and 385 mu of dry fields. The main industry is agriculture. Products include rice, wrinkled-skin peppers and Tingpai pickled vegetables. There is one elementary school covering grades one to six. School attendance is 100%. Xinyang village is orderly and well-kept with sturdy buildings. The rich woodlands and green slopes provide a potential base for the villagers to improve their livelihoods.

2.3.6 Dujiang (DJ) (Zenlei village, Dujiang township)

Zenlei administrative village in Dujiang township, Sandu county, comprises four natural villages: upper, mid, lower and Paizhang 排长, and covers an area of 0.52 km

2. According to local oral histories, the Sui ancestors migrated to Zenlei during the reign of Kangxi in the Qing dynasty.9 There are now 221 households in Zenlei with a total population of 1,017. 65% of the population are Sui minority. 35% are Miao minority. The Sui, Miao and Chinese languages are all used in everyday life. The Sui people of Zenlei can speak Miao, and the Miao people can speak Sui. Although both ethnic groups live in the same area and environment, each group has preserved its own culture and customs. The old buildings making up Zenlei are situated halfway up the mountain slopes, opposite the impressive buildings of Dujiang Old Town on the facing mountain. Below Zenlei are terraced rice paddies. Around it are ancient trees and bamboo woods. Mountains, woodland, rice terraces and the green tiles of the traditional minority houses set off against each other, merging into a glorious whole. There are over 200 houses, most of which are traditional wooden-framed structures. Fourteen houses are over 100 years old. In total there are 186 traditional-style houses and 110 granaries.

For centuries, the Sui and Miao have lived together harmoniously in Zenlei village, providing a model of ethnic unity and harmony between people and nature. The antique buildings are a microcosm of Sui culture and constitute an important heritage for researching traditional Sui culture and

architecture. In June 2002, Zenlei village was the first to be officially designated as a “Representative Minority Culture Village” by the Guizhou Provincial People’s Government.

2.3.7 Banliang (BL) (Banliang village, Tangzhou district)

Banliang village is located 10 km south of the Tangzhou district government, 2 km from the main road. It has an elevation of 790m and its climate is warm and humid. The total area of the village is 1.7 km2. The administrative village office is in Banliang. It oversees ten village groups comprising 271

households. It has a total population of 1,127 people (all are agricultural), of which 92.3% are Sui minority, 6.7% are Miao minority, and 1% belong to other minorities. There are 451 people of

employable age. Of these, only ten have graduated from senior high school, 110 have completed junior high school, and 149 have completed only elementary school. There are 835 mu of cultivated land, averaging 0.92 mu per person, of which 0.33 mu is rice paddy. The main natural resource is mountain woodland, with an average of 1.45 mu per person. Wild grasslands occupy 2,284.7 mu, of which 611.9 mu is cultivatable.

2.3.8 Jiaoli (JL) (Gaorong village, Jiaoli district)

Gaorong administrative village is situated in the north of Jiaoli district, Sandu Autonomous Sui County. It is 21 km from the county seat and 6 km from Jiaoli district government. It borders Yangdong village (阳东村) to the east, Qianjin village (前进村) to the south, Gaopai village (高排村) (Danzhai county) to

the west, and Gaozhai village (高寨村) (Danzhai county) to the north. Jiaoli district is a distinctively

Miao district. Over 80% of the population is Miao ethnicity and most people in Jiaoli speak Miao. Gaorong is a Sui village in a Miao district. It oversees eight village groups and has a total population of

1,376, comprising 203 households. There are 421 mu of cultivated land, 562 mu of mountain forest, and there is a narrow, unpaved road leading to the village from the district government.

Gaorong village is one of the poorer villages in Sandu county. The climate is warm with a long summer and a short winter. The winter is not too cold and the summer is not too hot. The Sui people here are hard-working and brave, kind and simple-minded, and can endure hardship and suffering. The village is in a basin with high mountains on both sides. The arable land is in the valley, whilst the mountain slopes are wooded. Further up the mountainside is thick forest belonging to Danzhai county. At the foot of the village is a small river which flows all year round. The source of the river is a cave near a mercury mine. Gaorong is in a Miao region and the villagers have taken on some of the customs of the Miao. However, they preserve the vast majority of traditional Sui customs. From ancient times until now, all village activities are arranged according to auspicious days in Lee Sui books. Some Sui shamans even go to the surrounding Miao villages to provide auspicious services according to the Lee Sui books.

2.3.9 Jiuqian (JQ) (Guchang village, Jiuqian township)

17

3 Historical Development of the Sui Dialects: Introduction

(Andy Castro)

3.1 Background

The currently accepted subgrouping of Sui dialects was made primarily on the basis of shared phonetic and phonemic traits (SDB 1958, Zhang Junru 1980, James Wei 2008, Stanford 2011). In chapters 4 and 5, we take another look at Sui subgrouping from a diachronic perspective. In other words, we examine how the Sui dialects have changed and diversified over time. Linguists generally agree that shared linguistic innovations provide the most robust basis for subgrouping related speech varieties (Thurgood 1982, 2003, Campbell 2004).

A thorough examination of the sound changes which have occurred in the various Sui vernaculars leads us to the conclusion that, while the traditional grouping of Sui into three broad dialect groups holds up from a synchronic perspective, the genetic affiliations are more complex. For convenience, we break Sandong dialect into four subdialects: Central Sui (SD, ZH); Western Sui (TP, AT, TZ); Eastern Sui (DJ, SJ, RL); and Southern Sui (JQ, JR, SW, SY). Historically, Pandong is most closely related to Central, Western and Eastern Sui, possibly branching off with Western Sui before undergoing some sound

changes in common with Eastern Sui (e.g., loss of preglottalisation and mutation of voiceless nasals). Southern Sui most likely branched off from the rest of Sui relatively early on, undergoing several unique phonemic innovations of its own (most of which were described by Castro, 2011). Thus Southern Sui is genetically more distant from Central Sui than Pandong dialect is.

Most strikingly, we find that the Yang’an dialect shares a large number of phonological innovations with Kam, so much so that in many ways it bears more resemblance to a dialect of Kam than of Sui. We tentatively suggest that Yang’an actually belongs to the Kam branch and, genetically at least, is not a dialect of Sui at all.

Finally we show that although the Sui dialects may have different historical origins, there are some cross-dialect similarities which lend a certain “Sui-ness” to all Sui dialects including Yang’an. Cross-dialectal borrowings and later sound changes which diffused across the Sui area have helped to engender a common Sui identity over the entire Sui region.

By way of introduction, we first present a phonology sketch of Sandong (Central) Sui. An understanding of Sui phonology assists greatly in informing our investigation into historical sound changes in the Sui dialects. We then note the specific challenges that such a historical comparison presents in the Sui context. Finally we describe our data sources and the transcription conventions that we employ in our historical analysis. Our analysis is expounded in chapters 4 (tone) and 5 (onsets and rimes).

3.2 Sui phonology sketch

The phonology of Sui has been described by numerous scholars (e.g., Zhang Junru 1980, James Wei 2008, 2011). We provide only a summary here. Sui is largely monosyllabic, although sesquisyllabic forms comprising a minor and a major syllable do exist (see section 3.3.3 of this chapter and section 4.3 of chapter 4). Our phonology sketch here is based on the pronunciation of Central Sui in Shuigen village, Sandong (SD). Simple phonology sketches for each of our sixteen data points are given in appendix G. 3.2.1 The Sui syllable

but we adhere to the traditional interpretation presented here. The rime comprises a nucleus (vowel) and a coda (vowel or consonant). The rime may also constitute a monophthong, in which case there is no coda.

Figure 3.1. The Sui syllable. The dotted box indicates an optional component.

Minor (or “reduced”) syllables occur only in combination with (and almost always preceding) major syllables which follow the above configuration. A minor syllable is always unstressed and consists of an onset and a neutral vowel (ə) rime which does not bear contrastive tone.

3.2.2 Consonants

Sui has 42 consonants which occur in the initial position. Six of these can also occur as codas. The traditional transcriptions of these consonants are shown in table 3.1, with alternative transcriptions, sometimes found in the literature, in parentheses.1 There are two phonemically contrastive forms of secondary articulation: palatalisation, which can occur on labial, alveolar or, extremely rarely, velar consonants; and labialisation, which can occur only on alveolar or velar consonants.2 This yields a total of over 60 phonemically distinct onsets. As we mentioned earlier, palatalisation could also be analysed as a /j/ medial and labialisation as a /w/ medial.

1By “traditional transcriptions” we mean the transcriptions adopted by most Sui scholars when transcribing Sui language data (e.g., Zhang Junru 1980, Pan and Wei 2004, Wei Maofan 2011).

2For example kjeu⁵ ‘addictive’ (JQ) and kʰjui³ ‘poor’ (SD). We have found no examples of palatalisation occurring on ʔw- or labialisation occurring on ʔɣ-, although these combinations are possible according to the phonemic framework we set out here.

syllable (σ)

onset (ω)

medial (μ) j or w

rime (ρ)

nucleus (ν) V

coda (κ) V or C

tone (τ)

initial (ι) C