Sociolinguistic Survey of the

Shabo of Ethiopia

Sociolinguistic Survey of the Shabo of Ethiopia

Linda Jordan, Hussein Mohammed, and Jillian Netzley

SIL International

®2015

SIL Electronic Survey Report 2015-019, December 2015 © 2015 SIL International®

Abstract

The Shabo language [sbf] of southwestern Ethiopia has been viewed in the past as an unlikely candidate for language development. The aim of this survey, conducted in November 2004, was to either prove or disprove that assessment. It was found that the Shabo are a very small and highly bilingual group, and their attitude toward the Majang people and language [mpe] is overwhelmingly positive. As the Shabo’s preferred second language, Majang is spoken at a high level of fluency. This study suggests that the Shabo are adequately bilingual in the sense that they are likely to benefit from literature and educational materials developed in the Majang language.

iii

Contents

1 Introduction

1.1 Geography

1.2 People and language 1.3 Other research

2 Goals of the research 3 Methodology

3.1 Procedures

3.1.1 Group and individual interviews 3.1.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation 3.1.3 Wordlists

3.2 Data sources

3.2.1 Group and individual interviews 3.2.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation 3.2.3 Wordlists

3.3 Data analysis

3.3.1 Group and individual interviews 3.3.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation 3.3.3 Wordlists

4 Results

4.1 Group and individual interviews 4.1.1 Multilingualism

4.1.2 Language use 4.1.3 Language attitudes 4.1.4 Attitudes to dialects 4.1.5 Social interaction patterns 4.1.6 Language vitality

4.1.7 Language development 4.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation 4.3 Wordlists

5 Evaluation of data

5.1 Group and individual interviews 5.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation 5.3 Wordlists

6 Conclusions and recommendations Appendix A

1

1 Introduction

The Shabo language is spoken by the Shabo people, few in number, who live near the Ethio-Sudanese border in and around the Gambela Region of southwestern Ethiopia. The Shabo's closest neighbors are the numerically superior Majang, whose culture and language are quite influential, as the two groups intermarry, trade, work and celebrate holidays together. Though the Shabo have close social ties to the Majang people, their language is distinct. The Shabo language is as yet an unclassified language presumed to be a member of the Nilo-Saharan family, which has undertaken a vast amount of lexical borrowing, more from Majang than from any other language (Bender 1977).

1.1 Geography

The Shabo people live in what used to be the Kafa Region, between Godere and Masha, among the Majang and Shekkacho [moy] (Lewis 2009). According to the current administrative divisions, most Shabo people now live in the Sheka Zone of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR) and the Majangir Zone of Gambela Region. Daniel (2003) also reports the existence of a Shabo population in the Salle Noono district of Oromia.

Map 1. Shabo language area

Source: map was created with AtlasGIS v4.0 and geographical data from World Database (WDB).

1.2 People and language

Matthias Brenzinger estimates that there are only 400–500 speakers of Shabo out of an ethnic population of 600 or more (Lewis 2009). There is no mention of the Shabo in the 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. The Shabo people call themselves “Sabu” and their language “Sabuyye.” They do not like the terms “Shako” and “Mekeyer,” names for the Shabo used by the Shekkacho and Majang,

respectively.

The Shabo make their living from resources found in the forest, mainly depending on hunting and honey-gathering, since neither farming nor raising livestock is common in their society. They also seek out employment offered by nearby coffee plantations and other opportunities that nearby towns provide. A few of them do make their living from subsistence farming, whereas the neighboring Majang raise the bulk of their own food by farming (Stauder 1971).

One tradition about the Shabo’s origin is that their ancestors were mother tongue speakers of Majang, but that their present language has changed a great deal since those times (Bender 1975). Based on the little data available to him at the time, including a wordlist gathered by Harvey Hoekstra, Bender (1977) tentatively classified Shabo together with Majang as a member of the Surmic branch of Nilo-Saharan. According to his lexicostatistical analysis, it has 22% commonality with Majang, no more than 11% with any other Surmic language, and up to 16% with Omotic languages. Shabo appears to have a great deal of lexical borrowing in its history, and Surmic is the grouping with which it has the highest number of lexical matches. Other past efforts to classify Shabo, based on very little data, included the idea that they might be related to a Murle [mur] offshoot (Bender 1975). In addition to his above-mentioned work, Bender (1994) presented some data on Shabo verb morphology in his grammatical comparison of the Koman speech varieties and Gumuz [guk].

Stauder (1970:109) mentions “Mikair” clans among the Majang, said to have come from the Sheko [she] (a neighboring Omotic group). Shabo does have some grammatical features, such as pronouns, that are more similar to Omotic languages like Ganza [gza]. In spite of this, it is almost certainly a Saharan language, according to Bender (1983). This is based on 40% of 176 words resembling Nilo-Saharan.

Unseth (1984) presented linguistic data showing that Shabo is indeed a separate language, not a variety of Majang. He collected 70 words from an informant who spoke Shabo as a child but

subsequently moved to a Majang area and spoke that language. A Majang accent may therefore be present in the wordlist items, affecting sounds like s, p and f, which are interchangeable in Majang. Unseth’s data shows that Shabo contains glottalized stops, which separate it from Majang, and bilabial implosives, which distinguish it from Omotic languages. The highest number of cognates with any language was found to be 20–29% with Majang, based on a conservative to a more liberal comparison count. As stated above, there has apparently been a large amount of borrowing in Shabo’s history. Though it seems linguistically closer to the Surmic language group than to the Koman group, it does contain a very high number of Koman cognates for a speech variety with no Koman neighbors.

1.3 Other research

Anbessa Teferra has conducted several studies of the Shabo language, including work on its classification with Unseth (1989). They consider it to be Nilo-Saharan but do not go into any detail on its position within that family. Anbessa has also worked on Shabo’s grammar (1991) and phonology (1995). Harold Fleming (1991) presented data on the preliminary classification of Shabo as Nilo-Saharan, considering it to be most closely related to Koman. This is based on the fact that the wordlists reveal a significant number of Koman words after the loanwords from Majang and Shekkacho are removed. Fleming (2002) also presented some data on Shabo verb morphology in his exploration of whether Shabo belongs to Nilo-Saharan or to a new African phylum. He believes that it is likely to be a major branch of its own within Nilo-Saharan.

Ehret (1995) is not convinced that Shabo can be classified as either Nilo-Saharan or Afro-Asiatic. He considers the words of Koman origin to be early loans. After identifying and removing these items along with the loanwords from Majang and Shekkacho, he found little evidence to support the Nilo-Saharan classification assigned by others and therefore regards Shabo as an isolate.

Daniel Aberra has also collected data on Shabo, studying its phonology (1998), pronouns (2003), morphology (2001, 2004) and typology (2005).

Schnoebelen (2009), like Ehret, believes that Shabo is best treated as an isolate. He is not convinced by the data used to defend the Nilo-Saharan hypothesis, asserting that the lexical support for this

2 Goals of the research

The main research goal of this survey conducted in November 2004 was to determine the optimal language for literature and educational materials in ethnically Shabo areas. The main concepts involved in addressing this question are language attitude and bilingualism. The objectives pertinent to these concepts include assessing the Shabo people’s attitudes toward and proficiency in both Majang and Shekkacho.

The purpose of this study was not to look at possible changes in attitude and language use over time, since the previous research done on Shabo has focused largely on description of the language and the attempt to classify it. In an effort to get an overview of the sociolinguistic situation and to find new information about language attitudes and multilingualism among the Shabo, the main strategy of the study was the use of questionnaires (described in section 3 below). The researchers hope this will provide a baseline for further studies that will compare the current data and conclusions to the future status of language use in the Shabo area.

The research team decided to collect a wordlist as well, though it was outside the scope of the survey’s sociolinguistic goals. There were two reasons for this. Firstly, the team wanted to use the same 322-item elicitation list that was used for other languages surveyed by SIL Ethiopia and the Institute of Ethiopian Studies (IES), enabling a direct comparison between those wordlists and the current one. Also, previously published Shabo wordlists have been shorter. The one compiled by Anbessa and Unseth (1989), which includes data both from their own fieldwork and from Hoekstra’s list as published by Bender (1983), includes 107 words. Fleming (1991) combined data from previous studies into a list of 268 words. The wordlist collected during this survey has already been consulted in a subsequent study (Schnoebelen 2009), and it is hoped that it will provide material for future comparative studies.

3 Methodology

Four different methods were used to accomplish the research goals. The procedures, data sources and analysis techniques for each are described below.

3.1 Procedures

3.1.1 Group and individual interviews

In Dushi village, the first community visited during this survey, a group sociolinguistic interview was conducted in order to get an overall picture of the sociolinguistic situation among the Shabo people (appendix A). The questionnaire was based on the S.L.L.E. Main Sociolinguistic Questionnaire as revised by Aklilu Yilma, Ralph Siebert and Kati Siebert (Wedekind and Wedekind 2002). It was further revised and retranslated into Amharic [amh] by Hussein Mohammed. Conducting this interview took several hours and covered the areas of multilingualism, language use, language attitudes, dialect attitudes, social interaction patterns, language vitality and language development. The interviewer used Amharic and was assisted by a local interpreter, who translated between Amharic and Shabo so that all could understand and contribute.

In Dushi, the group interview was followed by individual interviews with a cross-section of the population. These were also conducted in Yeri village, the second community visited during this survey. The individual questionnaire includes a subset of the questions found in appendix A, focusing more on language attitudes, social interaction, language vitality and language development. It serves primarily to double-check the accuracy of the information collected during the group interview. Again, the

3.1.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation

The Shabo people are found in an area of Ethiopia where both Majang and Shekkacho are spoken. Some bilingualism testing was therefore conducted to determine the level of proficiency in these languages and to complement the evidence of language shift away from Shabo. Because no bilingualism test such as a Sentence Repetition Test (SRT) has been developed for either Majang or Shekkacho, a questionnaire was used to investigate the Shabo’s self-reported proficiency in these languages.

The interview for bilingual proficiency was based on a questionnaire adapted from the US Foreign Service Institute Testing Kit, as reported by Grimes (1986). Its proficiency levels are based on those established by the US Foreign Service Institute. It was translated into Amharic and slightly modified for use in Ethiopia. In the field, the questions were either asked directly in Amharic or through an

interpreter, as with the individual interviews described in section 3.1.1 above.

Ten subjects were tested in Dushi village for purposes of evaluating this methodology and for obtaining an estimate of bilingual proficiency in that community. The questionnaire was administered orally, with each question to be answered by “yes” or “no”. All answers had to be “yes” through any given point in order to achieve at least the level of proficiency assigned to that set of questions (see appendix B). The exception was four items at the S-3 level, which required an answer of “no” in order to achieve level 3 proficiency.

3.1.3 Wordlists

During this survey, wordlists were collected using the 322-item elicitation list that was first compiled by Tim Girard (Wedekind and Wedekind 2002) and revised by the current SIL-Ethiopia survey team. The Shabo wordlist was collected in Dushi and checked in Yeri. Amharic was the main language of

elicitation, but Majang was used as necessary for clarification and discussion between the transcriber and wordlist contributors. A Majang wordlist was later collected and checked in Addis Ababa with mother tongue speakers from the Tepi area (see appendix C for both the Shabo and Majang lists). Amharic was the sole language of elicitation for the Majang list. These two wordlists were then compared to each other and to a list from Chara [cra], an Omotic language.

3.2 Data sources

3.2.1 Group and individual interviews

In the group interview (conducted in Dushi), there were 30 participants between 13 and 40 years of age, including 21 men and nine women. The survey team waited to begin the interview until at least ten participants were present. Since the interview was held in an informal setting, participants came and went as they saw fit. The information was taken as being from the group as a whole instead of from individuals within that group.

A total of 20 individual sociolinguistic interviews were conducted, ten in each village. The following general guidelines were used when selecting the sample:

Include at least two

• males/females

• with/without some formal education

• below/above 25 years of age.

3.2.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation

The bilingual proficiency self-evaluation questionnaire was administered to ten men in the village of Dushi. No women were tested, since in this traditional community they were not comfortable interacting with strangers and did not consent to being interviewed. Six of the subjects were aged 15–24 years, two were 25–34 years old and two were 35 or older.

3.2.3 Wordlists

The Shabo and Majang wordlists were each gathered with the assistance of one or more mother tongue speakers of the speech variety and double-checked with different mother tongue speakers.

3.3 Data analysis

3.3.1 Group and individual interviews

The answers to sociolinguistic interview questions were compared and evaluated in relation to the research goals. They were also evaluated in light of the bilingual proficiency self-evaluations and other observations.

3.3.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation

The results for all ten subjects were tabulated, listing the age, proficiency level and level description for each. It was noted how many have an estimated second language proficiency higher than level 3 (good, general proficiency).

3.3.3 Wordlists

The wordlist transcriptions from this survey and a previous SIL-IES joint survey of Chara (Aklilu 2002) were entered into WordSurv version 5.0 beta for lexicostatistical comparison. After lexical groupings were assigned manually, the program calculated the percent of similar lexical items.

4 Results

4.1 Group and individual interviews

4.1.1 Multilingualism

All those who participated in the group interview (conducted in Dushi) are mother tongue Shabo speakers. They are bilingual in Majang or Shekkacho, and their ability in these languages varies with age. The younger generation has more ability in Majang, while older people have more ability in Shekkacho. Four interviewees, who have had some formal schooling, are able to read and write in Amharic.

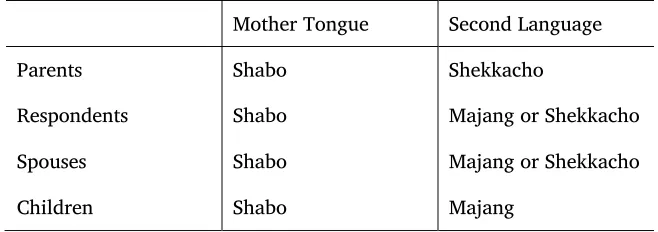

Table 1. Languages of interviewees and their relatives

Mother Tongue Second Language

Parents Shabo Shekkacho

Respondents Shabo Majang or Shekkacho

Spouses Shabo Majang or Shekkacho

Children Shabo Majang

4.1.2 Language use

The group interviewees stated that only Shabo is used when communicating with elders (see table 2). Shabo is also used within the family, when communicating with friends, at market, when praying at home, when angry and in dreams. Majang is used for all of these in addition to religious purposes (public worship), since church services are conducted in Majang. Shekkacho is only used when communicating with Shekkacho friends or at market. The Shabo count in their own language, using a system in which “one person” represents the number 20.

Table 2. Language used in various domains

Domain Language

With elders Shabo

For group religious purposes Majang

Within the family Shabo or Majang When praying at home Shabo or Majang When angry or dreaming Shabo or Majang

With friends or at market Shabo, Majang or Shekkacho

4.1.3 Language attitudes

Investigating patterns of intermarriage is one way of getting at a community’s attitudes toward other speech varieties. Intermarriage with a neighboring ethnolinguistic group will often correspond with a more positive attitude toward that group’s mother tongue. The research team asked about intermarriage patterns during this survey in order to indirectly investigate the Shabo’s attitudes toward Majang and Shekkacho.

According to the group interviewees, it is possible for a Shabo to marry a Majang. However, the Shekkacho never marry their daughters to Shabo men. In Dushi, one of the individual interviewees (a 55-year-old woman) is against marrying outside the ethnic group, but the other nine (all men) said that they would be willing to marry a non-Shabo. All, except the woman, would allow their children to marry outsiders. All the individual interviewees in Yeri said that they would be willing to marry a Majang. All of them would also allow their children to marry an outsider, particularly a Majang.

The individual interviewees in Yeri suggested that they would like their children to learn both Amharic and Majang.

The individual interviewees in Dushi expressed a positive attitude toward Majang and Amharic, while all the individual interviewees in Yeri indicated a positive attitude toward Majang and Shabo. However, the status they ascribe to Shabo and Majang differs. Only two interviewees give higher status to Shabo. One woman gives the same weight to both Majang and Shabo, and seven of them give higher status to Majang.

4.1.4 Attitudes to dialects

There is little or no dialect variation in Shabo. According to the group interviewees, varieties spoken in different areas of the "Shabo Forest" are the same. Three interviewees who have spent a year or more in Godere stated that the Shabo variety spoken in Dushi is similar to what is spoken in Godere. Since the Shabo live in a relatively small area, it seems that dialect variation is not a major issue.

4.1.5 Social interaction patterns

The Shabo celebrate Christian holidays with other Christians in the area. The group and individual interviewees in Dushi also said that Shabo people interact with Majang or Shekkacho friends in different ceremonies like weddings and funerals.

The Shabo of Dushi trade with Gemadiro, Gecha, Tepi, Meti and Kabo. Those in Yeri trade with Tepi Kobit'o, Meti and Kabo. Depending on whom they meet, the Shabo of both Dushi and Yeri use Majang, Shekkacho or even some Amharic for communication when they go to other villages to trade.

According to the group interviewees, most wives come from surrounding Shabo villages. However, seven of ten interviewees in Dushi have Majang blood through their mothers or grandmothers, and one interviewee has a Majang wife. They said that they communicate with their Majang relatives in the Majang language. Likewise, eight of ten interviewees in Yeri have Majang blood through their parents or grandmothers, and one has a Majang wife.

4.1.6 Language vitality

The group agreed that Shabo is “alive.” However, they claimed that the use of Shabo is decreasing because of the influence of the surrounding languages, namely Majang and Shekkacho. Furthermore, they pointed out the tendency to learn Amharic as another factor that could affect Shabo’s vitality.

The members of the group and six of the individual interviewees in Dushi doubt that their children will keep using the Shabo language. Three individuals in Dushi expect that their children will continue to use it, and one said that he could not predict what would happen in the future. Five of them said that they would not mind if the generation to come stops using Shabo. In Yeri, however, the people seem to be more positive about the vitality of Shabo. Nine interviewees there believe that their children will maintain the language, but the tenth interviewee doubts that the generation to come will use it.

4.1.7 Language development

The group interviewees expressed a positive attitude to publications in Majang. They also said that they would buy publications in Shabo. Nine of the individual interviewees in Dushi expressed their interest in the development of the Shabo language, but one man was against the idea. The individual interviewees in Yeri said that they would like their language to be written.

The group interviewees said that if there were schools to teach them to read and write their own language, they would go to them, but they have not yet seen anything written in Shabo. They also said that they would very much appreciate a Shabo radio program.

4.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation

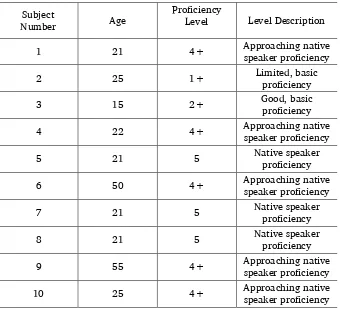

Majang is the preferred second language for all of the self-evaluation interviewees. All but two have an estimated Majang proficiency higher than level 3 (good, general proficiency). The following table shows the results.

Table 3. Majang proficiency self-evaluations Subject

Number Age

Proficiency

Level Level Description

1 21 4+ Approaching native speaker proficiency

2 25 1+ Limited, basic proficiency

3 15 2+ Good, basic proficiency

4 22 4+ Approaching native speaker proficiency

5 21 5 Native speaker proficiency

6 50 4+ Approaching native speaker proficiency

7 21 5 Native speaker proficiency

8 21 5 Native speaker proficiency

9 55 4+ Approaching native speaker proficiency

10 25 4+ Approaching native speaker proficiency

4.3 Wordlists

Based on the data gathered by this research team and Aklilu 2002, table 4 lists the percentages of similar lexical items in the wordlists of Shabo, Majang and Chara, an Omotic language.

Table 4. The percentage of similar lexical items in the wordlists of Majang, Shabo and Chara

MAJANG

17% SHABO

5 Evaluation of data

5.1 Group and individual interviews

The group interviewees stated that the second language of the younger generation tends to be Majang, while the older generation usually knows more Shekkacho. This is not apparent from the results of the bilingual proficiency self-evaluation. However, the group’s replies to questions about multilingualism across the generations do support this observation (see table 1).

The Shabo and Majang people appear to mix freely and have friendly relations. This observation also reinforces the idea that the Majang language is growing in influence among the Shabo. Though their own language still seems to be vital, the group interviewees currently use both the Shabo and Majang languages in most domains.

The individual interviewees in Yeri expressed a more positive attitude toward Shabo than did the Dushi interviewees. This is also shown by their ideas about language vitality, since nine of ten

interviewees in Yeri believe that their children will maintain the language. This could be because Yeri village is located farther from the main road and from nearby settlements than Dushi (see map 1).

In spite of their positive attitude toward Shabo, most of the Yeri interviewees ascribe higher status to Majang. The Dushi individual interviewees confirmed this by stating that they communicate with their Majang relatives in the Majang language.

5.2 Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation

Though the subjects were from a range of ages, the sample for the bilingual proficiency self-evaluation questionnaire was neither random nor representative. Therefore, the results can not be generalized to the wider Shabo population, especially since no women were tested. It is nevertheless interesting to note that Majang is the preferred second language for all subjects tested, even for those in the 35+ age category.

No clear patterns emerged from this small sample (see table 3). The only two subjects with an estimated Majang proficiency lower than level 3 (good, general proficiency) were 15 and 25 years of age. Of those rated at 4+ (approaching native speaker proficiency), two were aged 15–24 years, one was 25–34 years old and two were 35 or older. However, all three of those at level 5 (native speaker

proficiency) were under 25 years old.

As a pilot test for the self-evaluation methodology, this experience pointed out the shortcomings of the particular questionnaire that was used. Many of the questions were too long and complicated, especially when asked through an interpreter. There were also several questions that were not culturally appropriate for interviewing rural people with a subsistence lifestyle. If this methodology is used again in a similar cultural context within Ethiopia, either the questionnaire should be modified further or a simpler one should be found.

5.3 Wordlists

Because Shabo apparently has borrowed from both Nilo-Saharan and Omotic languages, the Shabo wordlist was compared to wordlists of Majang and Chara (see table 4). Shabo’s lexicon seems to be more closely related to Nilo-Saharan (represented by Majang) than Omotic (represented by Chara). The current study’s finding of 17% lexical similarity with Majang is in line with Unseth’s (1984) estimate of 20–29% and Bender’s (1977) 22%. Similarity with Chara is a very low 3%.

6 Conclusions and recommendations

The best language for literature and educational materials appears to be Majang in those Shabo areas that were visited during this survey. The attitude of the Shabo toward the Majang people and their language is overwhelmingly positive. Intermarriage with the Majang is common and accepted. Though the Shabo do have social interaction with the Shekkacho, it is not as extensive, and the Shekkacho language is not as important or widely spoken among them as Majang. As the Shabo’s preferred second language, Majang also seems to be spoken at a high level of fluency. Eight of ten interviewees were estimated at or approaching native speaker proficiency, according to the bilingual proficiency self-evaluation.

The Shabo language has been viewed in the past as an unlikely candidate for language

development. This study suggests that the Shabo are adequately bilingual in the sense that they are likely to benefit from literature and educational materials developed in the Majang language. As a very small and very bilingual group, the Shabo should be adequately covered by the language development work currently going on in Majang.

12

Appendix A

Sociolinguistic Questionnaire

A Identification of Respondent

1. Name

B Multilingualism

9. What is your first language?

10. Which other languages do you speak and understand? Do you speak one better than the others? Rank them.

11. Which of these can you read and write?

12. Apart from your own village, where have you lived at least for 1 year of your life? 12a. How long have you lived there?

12b. What languages did you speak there? 12c. Did the people there understand you well?

13. What was the first language your father learned as a child?

14. Which other languages does he speak and understand? Does he speak one better than the others? Rank them.

15. Can he read and write one of these languages? 16. What was the first language your mother learned?

17. Which other languages does she speak and understand? Does she speak one better than the others? Rank them.

18. Can she read and write any of these?

19. Which languages do your parents speak to each other?

20. Which languages do your brothers and sisters speak and understand? 21. Can they read and write any of these?

22. What was the first language your husband/wife learned?

23. Which other languages does he/she speak and understand? Does he/she speak one better than the other? Rank them.

24. Can he/she read and write one of these languages? 25. What is the first language of your children?

26. Which languages do your children speak and understand? Do they speak one better than the other? Rank them.

27. Can they read and write one of these languages? 28. What language do children in this village learn first?

29. Do many children learn another language before they start school? Which?

C Language Use

31. Which language do you speak most often…with your father? 32. With your mother?

33. With your brothers and sisters? 34. With your husband/wife? 35. With your children? 36. With your friends? 37. In your village? 38. At the local market?

39. With the elders of your village? 40. In the fields / at work?

41. At the big market? 42. At the clinic?

43. In church / mosque / traditional religious ceremonies? 44. With the administrators of the district?

45. When you are dreaming? 46. When you are praying at home? 47. When you are angry?

48. When you are counting money or things?

D Attitudes to Languages

49. Is it good to allow a young (MT speaker) man or woman to marry a woman or man who is not a (MT) speaker?

50. Does this happen very often?

51. Which language is best for a teacher to use in school? Why? 52. Which languages should be taught in school?

53. If a young person speaks (L2 / trade language) at home, would an old person be unhappy about it?

54. What is the most useful language to know around here? 55. Is it OK for your child to marry a non-MT speaking person?

E Attitudes to Dialects

56. Which villages speak MT exactly like you? (List them.)

57. Which villages speak your language differently- but you can still understand them? 58. Which speak it so differently that you don’t understand?

59. Which is the best village for an outsider to live in to learn your language? 60. Are there MT people who speak it poorly? Where do they live?

F Social Interaction Patterns

61. Which villages do most of your wives come from? 62. Which villages invite you for feasts and dances? 63. Which villages do you trade with?

G Language Vitality

65. Do you think that your people are in the process of changing? Do they adopt the customs of (an)other group(s)?

66. Do you know any MT people who do not speak MT anymore? Are there very many? Where do they live?

67. Do you think that young MT people speak MT less and less?

68. When the children of this village grow up and have children of their own, do you think those children will speak your language?

H Development of the Language

69. Which language do you think would be best to choose for making books and newspapers? Why?

70. Do you think it would be good to have something published in your language? What would you like most?

70a. Would it be good to have other written MT materials (books, magazines, or newspapers)? 71. If there were schools to teach you how to read and write in your language, would you

come to them?

72. Would you like your children to learn to read and write the mother tongue?

73. If there were books in your language, would you be willing to pay for them- say 2 Birr? [about the equivalent of a quarter (US$ 0.25)- insert an appropriate amount in local currency here]

74. Have you ever seen anything written in your language? What? 75. Have you ever tried to write in your language?

15

Appendix B

Bilingual proficiency self-evaluation (as in Grimes 1986)

S-0+ Can you speak a little of the second language (use the name)? (Minimum of 30 words, not counting or days of week.)

S-1 Can you tell someone how to get from here to the nearest school or church? Can you ask and tell the time of day, day of the week, date?

Can you order a simple meal?

Can you buy food in the market at a just price?

Can you buy a needed item of clothing or a bus or train ticket?

Can you understand and respond correctly to questions about where you are from, your marital status, occupation, date and place of birth?

Can you respond properly upon meeting people, introducing others and use appropriate leave-taking expressions?

Can you use the language well enough to assist someone who does not know the language, to cope with the situations or problems described above?

S-1+ (All S-1 requirements and at least three of S-2.)

S-2 Can you describe your present or most recent job or activity in detail?

Can you give detailed information about your family, your house, the weather today?

Can you hire someone to work for you and arrange details such as salary, qualifications, hours, specific duties?

Can you give a brief story of your life and tell of immediate plans and hopes?

Can you describe your home area, giving climate, terrain, types of plants and animals, crops, products made there, peoples and languages?

Can you describe what types of leaders you have and what each one does in leading the people? Or can you describe the way children are taught what they need to know to become adults? Can you describe why you do your job the way you do?

Do you feel confident that you understand what native speakers want to tell you on topics like the above, and that they understand you nearly all of the time?

Can you speak the language well enough to help someone else who does not know the language in coping with the situations or problems we have just mentioned?

S-2+ (All S-2 requirements and at least three of S-3.) S-3 (Answers should be no.)

Do you sometimes find yourself not knowing how to say something in the language? Are you sometimes unable to finish a sentence?

Do you find it difficult to follow and contribute to a conversation among native speakers who try to include you in their talk?

(Answers should be yes.)

Can you speak to a group of leaders about your work and be sure you are communicating what you want to, without obviously amusing or irritating them by your use of the language?

Can you listen and then summarize accurately a talk or an informal discussion on something you are interested in?

Can you defend your beliefs or those of your people against criticism from someone else? Can you cope as far as language is concerned with such difficult circumstances as a needed house repair, a mistaken encounter with a policeman, a serious social mistake made by a friend? Can you follow an argument on some social topic?

Can you serve as an informal interpreter on the above topics?

Do you think that you can talk about anything relating to your work, beyond just ordinary topics?

S-3+ (All S-3 requirements and at least three of S-4.)

S-4 In discussions at work, do you always have the words you need to say exactly what you want to say?

Can you change the way you talk, depending upon whether you are talking to educated people, close friends, those who work for you?

Can you serve as an informal interpreter for a leader from your mother tongue group who may not be able to speak the second language very well?

Do you almost never make a mistake?

Do you think you can carry out any work assignment as well in the language as in your mother tongue?

S-4+ In discussions on all subjects, are your words always appropriate and exact enough to enable you to convey your exact meaning?

S-5 Do native speakers react to you as they do to each other?

Do you sometimes feel more at home in the language than in your own mother tongue? Can you figure prices in your head in the language without slowing down?

17

Appendix C

Wordlists

The Shabo wordlist was collected in Dushi by James Kim and checked in Yeri by Linda Jordan. The Majang wordlist was collected and checked in Addis Ababa by Jillian Netzley.

eight brother (elder)

33

References

Aklilu Yilma. 2002. Sociolinguistic survey report on the Chara language of Ethiopia. SIL Electronic Survey Reports 2002-032, http://www.sil.org/silesr/2002/032/SILESR2002-032.pdf. (15 July, 2011)

Anbessa Teferra and Peter Unseth. 1989. Toward the classification of Shabo (Mikeyir). In M. Lionel Bender (ed.), Topics in Nilo-Saharan linguistics. Nilo-Saharan 3, 405–418. Hamburg: Helmut Buske. Anbessa Teferra. 1991. A sketch of Shabo grammar. In M. Lionel Bender (ed.), Proceedings of the Fourth

Nilo Saharan Conference Bayreuth, Aug. 30. Köln, Köppe Verlag. Hamburg: Helmut Buske.

Anbessa Teferra. 1995. Brief phonology of Shabo (Mekeyir). In Robert Nicolaï and Franz Rottland (eds.),

Fifth Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium. Nice, 24–29 août 1992, 169–193. Hamburg: Helmut Buske. Bender, M. Lionel. 1975. The Ethiopian Nilo-Saharans. Addis Ababa: Artistic Printers.

Bender, M. Lionel. 1977. The Surma language group: A preliminary report. Studies in African Linguistics 7. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University.

Bender, M. Lionel. 1983. Remnant languages of Ethiopia and Sudan. In Harold Marcus and Grover Hudson (eds.), Nilo-Saharan language studies 14, 336–354. East Lansing, MI: African Studies Center, Michigan State University.

Bender, M. Lionel. 1994. Comparative Komuz grammar. Afrika und Übersee77:31–54.

Daniel Aberra. 1998. Notes on the phonology of Shabo. Paper presented at the 10th Annual Seminar of ILS, June 1998.

Daniel Aberra. 2001. A comparison of Shabo and Koman words and their nominal inflections. Paper presented at the 8th Nilo-Saharan Colloquium, University of Hamburg, Institute of African and Asian Studies, August 23–25, Hamburg, Germany.

Daniel Aberra. 2003. Shabo pronouns. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies 3, 1692–1704. Addis Ababaː Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University. Daniel Aberra. 2004. Verb structures of Shabo. Paper presented at the 8th Nilo-Saharan Linguistics

Colloquium, February 16–19, Khartoum, Sudan. Daniel Aberra. 2005. Typological profile of Shabo. Ms.

Ehret, Christopher. 1995. Do Krongo and Shabo belong in Nilo-Saharan? In Robert Nicolaï and Franz Rottland (eds.), Fifth Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium, Nice, 24–29 août 1992, 389–402. Hamburg: Helmut Buske.

Fleming, Harold. 1991. Shabo: Presentation of data and preliminary classification. In M. Lionel Bender (ed.), Proceedings of the Fourth Nilo Saharan Conference Bayreuth, Aug. 30. Köln, Köppe Verlag.

Hamburg: Helmut Buske.

Fleming, Harold. 2002. Shabo: A new African phylum or a special relic of old Nilo-Saharan? Mother Tongue 7:1–37.

Grimes, Barbara F. 1986. Evaluating bilingual proficiency in language groups for cross-cultural communication. Notes on Linguistics 33:5–27.

Lewis, M. Paul (ed.). 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, 16th ed. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Nicolaï, Robert & Franz Rottland (eds.). 1995. Fifth Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium, Nice, 24–29 août

Schnoebelen, Tyler. 2009. (Un)classifying Shabo: Phylogenetic methods and results. In Peter K. Austin, Oliver Bond, Monik Charette, David Nathan and Peter Sells (eds.), Proceedings of Conference on Language Documentation and Linguistic Theory 2. London: SOAS.

Stauder, Jack. 1970. Notes on the history of the Majangir and their relationships with other ethnic groups of southwest Ethiopia. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, 1966 3:104–115. Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University.

Stauder, Jack. 1971. The Majangir: Ecology and society of a southwest Ethiopian people. London: Cambridge University Press.

Unseth, Peter. 1984. Shabo (Mekeyir): First discussions of classification and vocabulary. Language Miscellanea 11. Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University.

Wedekind, Klaus and Charlotte Wedekind. 2002. Sociolinguistic survey report of the Asosa - Begi - Komosha area: Part II. SIL Electronic Survey Reports 2002-055,