Major Depression in Adults

Albert Michael, Alison Jenaway, Eugene S. Paykel, and Joe Herbert

Background: The authors sought to examine whether

levels of dehydroepiandrosterone are abnormal in depression.

Methods: Three groups of subjects aged 20 – 64 were

studied: 44 major depressives, 35 subjects with partially or completely remitted depression, matched as far as possible for age and drug treatment, and 41 normal control subjects. Dehydroepiandrosterone and cortisol in saliva were determined from specimens taken at 8:00AM

and 8:00PM on 4 days.

Results: The mean age of the three groups did not differ.

Dehydroepiandrosterone was lowered at 8:00AMand 8:00

PMcompared with control subjects. Values for the remitted

group were intermediate. Dehydroepiandrosterone levels at 8:00 AM correlated negatively with severity of

depres-sion and were not related to drug treatment or smoking, but decreased with age (as expected). Cortisol was ele-vated in depression in the evening. The molar cortisol/ dehydroepiandrosterone ratio also differentiated those with depression from the control group.

Conclusions: Lowered dehydroepiandrosterone levels are

an additional state abnormality in adult depression. Ad-renal steroid changes are thus not limited to cortisol. Because dehydroepiandrosterone may antagonize some effects of cortisol and may have mood improving proper-ties, these findings may have significant implications for the pathophysiology of depression. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:989 –995 © 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry

Key Words: DHEA, cortisol, depression, adults, saliva,

rhythm

Introduction

T

he adrenal cortex secretes a wide spectrum of steroid hormones, but nearly all attention on endocrine ab-normalities associated with affective disorder has been reserved for cortisol. Hypersecretion of cortisol occurs inabout 50% of cases, whether assessed by increased basal levels, or by heightened resistance to the suppressive feedback effects of dexamethasone (Butler and Besser 1968; Carroll and Mendels 1976; Murphy 1991a). Abnor-mal corticoid secretion may mark either the course of depression or predict subsequent relapse following appar-ent recovery (Holsboer 1992). Increased levels of glu-cocorticoids, deriving either from endogenous sources (as in Cushing’s syndrome) or exogenous ones (as during steroid therapy) are known to induce abnormal affective states, particularly depression (Dorn et al 1997; Lewis and Smith 1983; Starkman et al 1981). Administration of metyrapone, a compound that reduces cortisol levels, has been reported to be beneficial in depression (O’Dwyer et al 1995). In a recent study of depressed children and adolescents, we have identified those with comorbid dysthymia (i.e., “chronic depression”) as being most likely to show evening hypercortisolaemia (Goodyer et al 1996; Herbert et al 1996).

There are, however, other adrenal steroids that may be equally as significant for understanding the psychopathol-ogy of depression. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is particularly interesting. The sulphated form of DHEA (DHEAS) is the most abundant circulating steroid in man, although information on its function has been elusive until recently. Blood DHEA and DHEAS increase markedly during early childhood and again during puberty (Parker et al 1978). Levels peak in early adulthood and decrease equally markedly thereafter (2–3% per year), so that by age 60 they are about one third of those at age 20 (Orentreich et al 1992). Chronic physical ill-health or more acute events, such as imminent surgery, result in an elevated cortisol level but lowered DHEA and altered cortisol/DHEA ratios (e.g., Gray et al 1991; Hedman et al 1992; Spratt et al 1993). One important feature of DHEA(S) is thus that it can alter independently of cortisol both during normal life and in illness. A second one is that there is increasing evidence that DHEA can act as an antagonist to glucocorticoids (Blauer et al 1991; May et al 1991; Shafagoj et al 1992).

The relevance of this to psychiatric disorder has been shown recently. An extensive study of depression in adolescents showed that about 30% have abnormally low From the Departments of Psychiatry (AM, AJ, ESP) and Anatomy (JH), University

of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Address reprint requests to Joe Herbert, University of Cambridge, Department of Anatomy, Cambridge CB2 3DY, United Kingdom.

Received March 6, 2000; revised June 13, 2000; accepted June 13, 2000.

© 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry 0006-3223/00/$20.00

DHEA levels; however, this occurred at a different time (in the morning) than high (evening) cortisol (Goodyer et al 1996; Herbert et al 1996). Levels of DHEAS were not significantly altered by depression (Goodyer et al 1996). Depressed adolescents with high cortisol/DHEA ratios and experiencing recent adverse life events were unlikely to have recovered 36 weeks later (Goodyer et al 1998). Whether the new findings on DHEA in adolescents apply to adults with major depressive disorder is not known. One report of DHEA levels in adult depressives was carried out on only nine depressed men compared with nine control subjects, and showed that DHEA levels at 8:00AMor 4:00 PMwere no different in the two groups (Osran et al 1993); however, the diurnal decrease in DHEA was less in the depressed group than the control subjects. More recently, the daily minima in DHEA levels have been reported to be increased in depression (26 cases; Heuser et al 1998). There is also a report of decreased cortisol/DHEA ratios in anorexia nervosa (Devesa et al 1988; Zumoff et al 1983), which return to normal upon restoration of normal weight (Winterer et al 1985). “Well-being” was increased by administration of DHEA to middle-aged men and women, and plasma DHEA (but not DHEAS) correlated positively with well-being in postmenopausal women (Cawood and Bancroft 1996; Morales et al 1994). Recent preliminary reports in depressed adults noted that ingestion of oral DHEA over 4 weeks improved mental state and memory function (Wolkowitz et al 1995, 1999). In patients with Addison’s disease who lack DHEA(S), supplementation improved well-being and reduced depression and anxiety scores (Arlt et al 1999). These findings on DHEA suggest that endocrine abnormalities in depression may extend to steroids other than cortisol, and that the psychopathology of this condition may be more complex than is presently thought.

This article reports, for the first time, lowered (morning) DHEA in major depression in adults compared with a control group of age- and gender-matched subjects. Be-cause concurrent drug treatment is a confounding factor in such studies, this conclusion is reinforced by the inclusion of an additional control group of subjects whose depres-sion had undergone remisdepres-sion, most of whom were still taking anti-depressant treatment.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

Three groups aged 20 – 64 years were studied.

MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER. There were 44 subjects with depression (12 male, 32 female), aged 20 – 64 years, recruited either as inpatients (36) or from an outpatient (8) clinic. Subjects were accepted only if free from other disorders (see below). All subjects met DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric

Association 1994) for unipolar major depressive disorder, single or recurrent episodes (moderate or severe) without psychotic symptoms. Smoking, alcohol intake, and current drug therapy were recorded.

REMITTED DEPRESSION. Thirty-five subjects (14 male, 21 female) with a previous episode of depression but who had recovered (i.e., no longer met DSM-IV criteria for major depres-sive disorder), were collected from follow-up outpatients. These subjects were either in complete or partial remission. The 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale (HAM-D; Hamilton 1967) scales were completed for each subject. Smoking, alcohol intake, and current drug therapy were recorded

NORMAL CONTROL SUBJECTS. Forty-one normal control subjects (14 male, 27 female) were recruited from hospital staff and age matched with the depressed group. Saliva was collected as for the other two groups. These subjects did not complete the psychiatric rating scales, and were apparently free of current illness (assessed from history). Smoking and alcohol intake were recorded. In all groups, liver function tests and urine screening were carried out if drug or alcohol abuse was suspected.

All subjects provided written informed consent following complete description of the study, which was approved by the Cambridge Local Ethics Committee.

Procedures

RATINGS. Subjects in the first two groups were assessed using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the HAM-D, and the Clinical Interview for Depression (CID); the latter was divided into depression and anxiety total scores (Overall and Gorham 1962; Paykel 1985).

CORTISOL AND DHEA IN THE SALIVA. Four salivary samples were collected at 8:00AM, and another four at 8:00PM, usually on consecutive days. Subjects were instructed not to clean their teeth within 2 hours of collecting saliva, to wash out their mouths with clean water immediately before collection, and to obtain about 5 mL of saliva by spitting into a plastic tube; no salivation aids were used. Samples were taken individually into prelabeled tubes supplied by the laboratory. They were stored in the freezing compartments (220°C) of the subjects’ refrigerators before being transferred to the laboratory.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS. Between-variable correlations and between-group comparisons were made using two-way, univar-iate, or repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs; with appropriate covariances) or nonparametric statistics (Kruskal– Wallis [K-W] and Mann–Whitney [M-W] tests). All tests are two tailed.

Results

Subjects

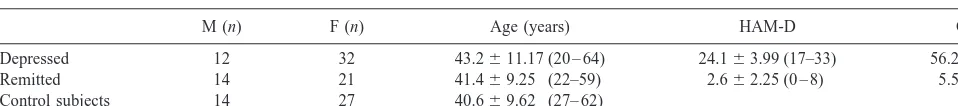

Table 1 shows the age and gender distribution of the three samples. Neither age (K-Wx250.57, p5ns) nor gender (x2 5 1.31, p 5 ns) differed significantly between the groups; however, smoking (defined as more than five cigarettes per day) was significantly more frequent in the depressed group (K-Wx258.96, p,.01). There were 12 smokers in the depressed group (27.3%), compared with seven in the remitted group (20.0%) and only two (4.9%) in the control subjects group. The mean HAM-D scores in the depressed group were no different in smokers and nonsmokers [F(1,42) 5 2.6, p 5 ns]. Alcohol intake (reported units per week) did not differ between the groups (K-Wx25 0.72, p5 ns).

The HAM-D scores for the depressed group were significantly greater than the remitted group (M-W U 5

7.5, p , .001; Table 1). All the depressed group had HAM-D scores of greater than 17; the highest score in the recovered group was 8. In the depressed group, there were highly significant correlations between the HAM-D and both CID depression (Spearman r 5 .63, p, .001) and CID anxiety scores (r 5.50, p,.001).

Drugs

Of the depressed group, 41 were taking psychotropic drugs; three were not. Of the recovered group, 26 were also taking drugs, and nine were drug free.

In the depressed group, 31 were taking a single drug, nine were taking two, and one was taking three; 14 were on tricyclic antidepressants, 18 on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and nine on monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). In addition to their primary medication, 10 were also taking lithium (as an adjunct to antidepressant treatment), one was taking benzodiaz-epines, and one sodium valproate (as an antidepressant). In

the recovered group, 10 were on TCAs, 14 were on SSRIs, and one was on MAOIs. Six were also taking lithium.

Salivary Steroids

DHEA. At both 8:00 AM and 8:00 PM, DHEA was negatively correlated with age (Spearman:AMr 5 2.36, p, .0001; PM r 5 2.33, p , .0001). In male subjects, DHEA (but not cortisol) was also higher (t tests; p,.02); there was no significant difference in age.

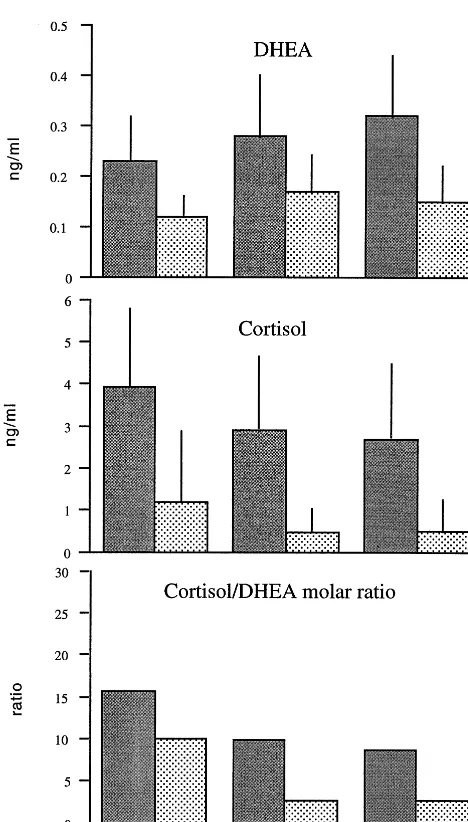

A two-way ANOVA (group and smoking [yes/no] as factors, age as covariate) showed that both morning and evening levels of salivary DHEA were significantly dif-ferent between the groups [DHEAAMF(6,98)53.5, p,

.02; PM F(6,98)53.4, p , .02; Figure 1); there was no main effect of smoking and no interaction between smok-ing and group. Further univariate ANOVAs showed that morning DHEA was significantly lower in depressed than control groups, whereas evening DHEA was lower in depressed compared to remitted groups (Bonferroni test, p,.05; Figure 1, top). A repeated-measures multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) on both morning and evening DHEA (age as covariate) also showed significant group effects [F(2,105)5 3.55, p5 .03].

Within the depressed group, there was a highly signif-icant negative correlation between HAM-D scores and morning DHEA (Spearmanr 5 2.49, p,.01; Figure 2). Similar associations were found with CID total depression (r 5 2.38, p,.01) and total anxiety scores (r 5 2.37, p,.05; Table 2). Evening DHEA correlated significantly only with the CID anxiety score (Table 2).

In the depressed group, morning DHEA was not signif-icantly lower in smokers than nonsmokers [F(1,38)53.9, p 5 .06]. There was no association between age and HAM-D scores. In the remitted group, those currently on medication had higher HAM-D scores than those who were drug-free (M-W U53.7, p,.001) and also higher PMcortisol levels (U52.3, p,.02), but no differences in DHEA.

CORTISOL. There were no correlations between

cor-tisol and age at either time point. Corcor-tisol (8:00 AM, 8:00PM) was significantly higher in the saliva of depressed subjects than the other two groups at both time points

Table 1. Characteristics of the Sample

M (n) F (n) Age (years) HAM-D CID

Depressed 12 32 43.2611.17 (20 – 64) 24.163.99 (17–33) 56.269.75 Remitted 14 21 41.469.25 (22–59) 2.662.25 (0 – 8) 5.564.81 Control subjects 14 27 40.669.62 (27– 62)

[AMF(2,117)54.9, p,.01;PMF(2,117)55.4, p,.01; Figure 1, middle). Salivary cortisol in the depressed subjects differed significantly from the control subjects and remitted groups (AMp,.05,PMp,.05; Bonferroni test). There were no significant correlations within the depressed group between cortisol at either time point and HAM-D, CID depression, or CID anxiety scores. A repeated-measures MANOVA, taking morning and evening levels of each hormone as dependent variables and age and smoking as covariates, showed significant group effects for cortisol [F(2,105)55.96, p 5.01).

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SALIVARY CORTISOL AND DHEA. Overall, there were highly significant

correla-tions between morning and evening levels of both cortisol and DHEA. There were also significant associations be-tween morning cortisol and DHEA. In the depressed group, there were similar associations between morning and evening levels of both cortisol and DHEA but not for morning cortisol and DHEA (Table 3).

MOLAR CORTISOL/DHEA RATIOS. Overall, there

were significant differences between the groups for both morning (K-Wx2531.0, p,.0001) and evening (x25

28.1, p , .0001) molar cortisol/DHEA ratios (Figure 1, bottom). Group comparisons showed that the depressed group differed significantly from the recovered subjects (AM x2 5 13.1, p 5 .0003; PM x25 20.9, p , .0001), whereas the control subjects and the recovered groups were indistinguishable (x25 2.2 and 0.2; ps5 ns). Figure 1. Depression is associated with lowered

dehydroepi-androsterone (DHEA), raised salivary cortisol, and elevated cortisol/DHEA ratios. The mean (6 SD) salivary levels of DHEA, cortisol, and the molar cortisol/DHEA ratio at either 8:00AM(gray bars) or 8:00PM(patterned bars) in three groups of subjects (depressed, recovered depressive, and normal control) are shown. Significance levels given in text.

Figure 2. The relation between salivary dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels at 8:00AMand Hamilton Rating Scale (Hamilton 1967) scores in the depressed subjects.

Table 2. Associations between Salivary Steroids and Psychometric Scores in the Depressed Group (n544)

HAM-D CIDd CIDa

DHEA (8:00AM) 20.48a

20.38a

20.37a DHEA (8:00PM) 20.08 20.09 20.28 Cortisol (8:00AM) 20.20 20.06 20.12 Cortisol (8:00PM) 0.13 20.12 20.04

HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale (Hamilton 1967); CIDd, Clinical Interview for Depression (Depression scale); CIDa, Clinical Interview for Depression (Anxiety scale); DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone.

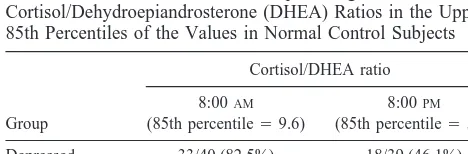

Taking the 85th percentile morning cortisol/DHEA ratio of the control group as an arbitrary (post hoc) cut-off, 82.5% of the depressed group had ratios that were equal to or greater than this value (control 15%). The correspond-ing result for the ratio at 8:00PMwas 46% (Table 4).

Discussion

The principal new finding of this study is that mean levels of DHEA in the saliva of depressed adults are lower than those in normal control subjects. There are a number of possible confounding variables that need to be considered before this endocrine parameter can be added to the known pathophysiology of this condition in adults.

The first, and most obvious, is the coincident effect of the antidepressant treatment being taken by the depressed subjects. We attempted to control for this by recruiting a number of remitted depressives, the majority of whom were still taking antidepressant treatment. It was notice-able that DHEA levels in this group as a whole fell between that in the depressed subjects and the normal control subjects. As might be expected, in the remitted group the HAM-D scores of those who continued treat-ment were higher than those who were drug free; however, separating those on antidepressant drugs failed to show any significant effect on DHEA levels, though the num-bers in each group are not large. The possible role of drug treatment needs to be re-examined on a much larger population than we were able to gather, but there is no

evidence from our results that drug treatment itself was responsible for the lower levels of DHEA recorded in depressed subjects. The concomitant findings of elevated salivary cortisol in the depressed (compared to the other two groups) reinforces the conclusion that lowered morn-ing DHEA is a state-dependent feature of at least a proportion of depressed subjects. Raised cortisol (in both blood and saliva) is a well-known association with this condition and is not the result of coincident drug therapy (Butler and Besser 1968; Gold et al 1988).

The association between DHEA and depression was strongly supported by the finding of a negative correlation between morning DHEA and HAM-D scores in the depressed group. This results both supports the conclusion that morning DHEA levels may be a state-related feature of depression, and further argues against a simple drug-related effect on DHEA. The fact that no such association was found for cortisol suggests that there may be differ-ences in the way that these two steroids relate to the depressed state, or may reflect the limited range of severity within the currently depressed sample.

Age is another possible confounding factor, because DHEA decreases with age (Orentriech 1992); however, our groups were well balanced for age and— had this been a factor— both morning and evening DHEA levels would have been expected to decline. Smoking was more prevalent in the depressed subjects; but smoking has been found to raise DHEA(S) levels (Khaw et al 1988), and so this effect, if present, would act against the findings we report. Moreover, statistical analysis failed to show an independent effect of smoking on DHEA levels in our sample.

We measured levels of DHEA and cortisol twice daily for 4 days. Steroid levels may fluctuate for a number of reasons, but the 4-day mean would have eliminated most of these adventitious sources of variation. Salivary levels of both DHEA and cortisol correlate well with those in the blood (Goodyer et al 1996; Guazzo et al 1996; Woolston et al 1983); in both cases, levels in the saliva represent about 5% of those in the blood. There is now a considerable literature on the reliability of measuring steroids in the saliva, and the way that such levels track those in the blood (Kirshbaum and

Table 3. Spearman Correlations between Salivary Cortisol and Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in All Subjects (n5107) or in the Depressed Group Alone (n544)

All subjects Depressed group only

DHEA (8:00AM)

DHEA (8:00PM)

Cortisol (8:00AM)

DHEA (8:00AM)

DHEA (8:00PM)

Cortisol (8:00AM)

DHEA (8:00PM) .72a .66a

Cortisol (8:00PM) .24b .01 .24 .13

Cortisol (8:00PM) 2.03 .11 .45a

2.15 2.04 .39a

ap,.01. bp,.05.

Table 4. The Number of Each Group Having Molar Salivary Cortisol/Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) Ratios in the Upper 85th Percentiles of the Values in Normal Control Subjects

Group

Cortisol/DHEA ratio

8:00AM

(85th percentile59.6)

8:00PM

(85th percentile55.7)

Depressed 33/40 (82.5%) 18/39 (46.1%) Recovered 11/34 (32.4%) 2/34 (5.9%) Control subjects 6/41 (14.2%) 6/40 (15.0%)

Overall significance: 8:00AMx2540.4 (p,.01); 8:00PMx2518.8 (p,

Hellhammer 1994). It seems highly likely, therefore, that depressed subjects have lower levels of blood DHEA in the morning, though the exact shape of the diurnal variation in DHEA needs to be examined more closely. A major conclu-sion, however, is that changes in DHEA may not be parallel to those in cortisol. The latter are more obvious in the evening (confirming previous reports: e.g., Seckl et al 1990; review by Murphy 1991a), though morning cortisol is also elevated. Whether the same subjects show both changes in cortisol or DHEA, or whether these can occur independently, could not be reliably determined from our study on about 40 subjects but should be become apparent when much larger popula-tions are examined. For the same reasons, we cannot reliably analyze the relation between DHEA and depression in male and female subjects separately in this study, nor assess the contribution of individual drugs to the endocrine levels observed in the depressed or comparison groups.

Levels of cortisol and DHEA in the saliva (as in the blood) show diurnal changes, with higher values at 8:00 AM than 8:00 PM (Krieger et al 1971); however, the amplitude of the cortisol rhythm is much greater than DHEA. Hence, the molar cortisol/DHEA ratio in control subjects was 8.3 at 8:00AMbut only 2.7 at 8:00PM(i.e., a three-fold change across 12 hours). This indicates that tissues, including the brain, are exposed to very different relative concentrations of cortisol and DHEA during the day. In view of the accumulating evidence that DHEA can act as an antagonist to corticoids (Blauer et al 1991; May et al 1991), it was noteworthy that the molar cortisol/DHEA ratios (particularly at 8:00 AM) clearly separated depressed and normal subjects. Women, not currently depressed, but with higher morning salivary cortisol levels and subsequently experiencing an adverse life event, have been shown to be at increased risk of becoming depressed within the following 12 months (Harris et al, in press); treatments designed to lower cortisol have been found to decrease levels of depression (Murphy 1991b; O’Dwyer et al 1995; Reus et al 1997). Dehydroepiandrosterone antagonizes the damaging ac-tions of corticosterone on cultured hippocampal neurons (Kimonides et al 1999), and there is some evidence for its being antidepressive (Wolkowitz et al 1995, 1997, 1999). Cortisol/DHEA ratios have been found to predict the course of depression in adolescents (Goodyer et al 1998), which suggests that measuring both may give a more complete picture of the steroidal changes associated with depression. If cortisol does affect either onset or recovery (O’Toole et al 1997), and if DHEA acts as an effective antagonist to cortisol in this context, then both may need to be taken into account.

Comorbid anxiety is common in depression. In this study, relationships with morning salivary DHEA were similar to depression as assessed by the CID, but evening DHEA was

associated only with anxiety. This would not necessarily apply to pure anxiety disorder, in which depression and anxiety are not so closely related as in this sample.

The findings in this article confirm and extend those already reported on first-onset depression in 8- to 16-year-olds, on a population largely free of antidepressant treat-ment (Goodyer et al 1996; Herbert et al 1996). Depressed subjects in this age group also show raised evening salivary cortisol and lower morning DHEA, and the fact that the results on the two groups are so similar increases the reliance that can placed on either. The main conclusion from these studies is that alterations in DHEA, a steroid with known actions on the brain, may be an intrinsic feature of depression in adults as well as in adolescents, and this finding may give added insight into the psycho-pathology of this condition.

We thank Helen Shiers and Sarah Cleary for the assays. Conducted within the MRC co-operative group in Brain, Behaviour and Neuropsychiatry.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994): Diagnostic and

Sta-tistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC:

American Psychiatric Press.

Arlt W, Callies F, van Vlijmen JC, Koehler I, Reinicke M, Bildingmaier M, et al (1999): Dehydroepiandrosterone re-placement in women with adrenal insufficiency. N Engl

J Med 314:1013–1018.

Blauer KL, Poth M, Rogers WM, Bernton EW (1991): Dehydro-epiandrosterone antagonises the suppressive effects of dexa-methasone on lymphocytes. Endocrinology 129:3174 –3179. Butler PWP, Besser GM (1968): Pituitary-adrenal function in

severe depressive illness. Lancet 1(7554):1234 –1236. Carroll BJ, Mendels J (1976): Neuroendocrine regulation in

depression. In: Sachar EJ, editor. Hormones Behavior and

Psychopathology. New York: Raven.

Cawood EHH, Bancroft J (1996): Steroid hormones, the meno-pause, sexuality and well-being of women. Psychol Med 26:925–936.

Devesa J, Perez-Fernandez R, Bokser L, Casanueva FF (1988): Adrenal androgen secretion and dopaminergic activity in anorexia nervosa. Horm Metab Res 20:57– 60.

Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, Dubbert B, Gold PW, Chrousoos GP (1997): The longitudinal course of psychopa-thology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercor-tisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:912–919.

Gold PW, Goodwin FK, Chrousos GP (1988): Clinical and biochemical manifestations of depression. Relation to neuro-biology of stress. N Engl J Med 319:413– 420.

Goodyer IM, Herbert J, Altham PME (1998): Adrenal secretion during major depression in 8 to 16 year olds III. Influence of cortisol/DHEA ratio at presentation on subsequent rates of disappointing life events and persistent major depression.

Goodyer IM, Herbert J, Altham PME, Secher S, Shiers HM (1996): Adrenal secretion during major depression in 8 to 16 year olds I. Altered diurnal rhythms in salivary cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): At presentation. Psychol

Med 26:245–256.

Gray A, Feldman HA, McKinley JB, Longcope C (1991): Age, disease and changing sex hormone levels in middle-aged men. Results of the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 73:1016 –1025.

Guazzo EP, Kirkpatrick PJ, Goodyer IM, Shiers HM, Herbert J (1996): Cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate in the cerebrospinal fluid of man: Relation to blood levels and the effects of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:3951–3960.

Hamilton M (1967): Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 6:278 –296. Harris TO, Borsanyi S, Messari S, Stanford K, Cleary SE, Shiers

HM, et al (in press): Morning cortisol as a risk factor for subsequent major depressive disorder in adult women. Br J

Psychiatry.

Hedman M, Nilsson E, de la Torre B (1992): Low blood and synovial fluid levels of sulpho-conjugated steroids in rheu-matoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 10:25–30.

Herbert J, Goodyer IM, Altham PME, Secher S, Shiers HM (1996): Adrenal steroid secretion and major depression in 8 to 16 year olds II. Influence of comorbidity at presentation.

Psychol Med 26:257–263.

Heuser I, Deuschle M, Luppa P, Schweiger H, Weber B (1998): Increased diurnal plasma dehydroepiandrosterone in de-pressed patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:3130 –3133. Holsboer F (1992): The hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical

system. In: Paykel ES, editor. Handbook of Affective

Disor-ders. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill, 267–287.

Khaw K-T, Tazuke S, Barret-Connor E (1988): Cigarette smok-ing and levels of adrenal androgens in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 318:1705–1709.

Kimonides VG, Spillantini MG, Sofroniew MV, Fawcett JW, Herbert J (1999): Dehydroepiandrosterone antagonizes the neurotoxic effects of corticosterone and translocation of stress-activated protein kinase 3 in hippocampal primary cultures. Neuroscience 89:429 – 436.

Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH (1994): Salivary cortisol in psychoendocrine research: Recent developments and applica-tions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 19:313–333.

Krieger DT, Allen W, Rizzo R, Krieger HP (1971): Characteri-sation of the normal temporal pattern of plasma corticosteroid levels. J Clin Endocrinol 32:266 –284.

Lewis DA, Smith RE (1983): Steroid-induced psychiatric syn-dromes. J Affect Disord 5:319 –332.

May M, Holmes E, Rogers W, Poth M (1991): Protection from glucocorticoid induced thymic involution by dehydroepi-androsterone. Life Sci 46:1627–1631.

Morales AJ, Nolan JJ, Nelson JC, Yen SSC (1994): Effects of replacement dose of dehydrepiandrosterone in men and women of advancing age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:1360 –1367. Murphy BEP (1991a): Steroids and depression. J Steroid Mol

Biol 38:537–559.

Murphy BEP (1991b): Treatment of major depression with steroid suppressive drugs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 39: 239 –244.

O’Dwyer A-M, Lightman SL, Marks MN, Checkley S (1995): Treatment of major depression with metyrapone and hydro-cortisone. J Affect Disord 33:123–128.

Orentreich N, Brind JL, Vogelman JH, Andres R, Baldwin H (1992): Long-term longitudinal measurements of plasma dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in normal men. J Clin

Endo-crinol Metab 75:1002–1004.

Osran H, Reist C, Chen CC, Lifrak ET, Chicz-DeMet A, Parker LN (1993): Adrenal androgens and cortisol in major depres-sion. Am J Psychiatry 150:806 – 809.

O’Toole SM, Sekula LK, Rubin RT (1997): Pituitary-adrenal-cortical axis measures as predictors of sustained remission in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 42:85– 89.

Overall JE, Gorham DR (1962): The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep 10:799 – 812.

Parker LN, Sack J, Fisher DA, Odell WD (1978): The adren-arche: Prolactin, gonadotropins, adrenal androgens and corti-sol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 46:396 – 401.

Paykel ES (1985): The clinical interview for depression: Devel-opment, reliability and validity. J Affect Disord 9:85–96. Reus VI, Wolkowitz OM, Frederick S (1997):

Antiglucocorti-coid treatments in pschiatry. Psychoneuroendocrinology 22: S121–S124.

Seckl J, Campbell JC, Edwards CRW, Christie JE, Whalley LJ, Goodwin GM, Fink G (1990): Diurnal variation of plasma corticosterone in depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 15: 485– 488.

Shafagoj Y, Opuku J, Quereshi D, Regelson W, Kalimi M (1992): Dehydroepiandrosterone prevents dexamethasone-induced hypertension in rats. Am J Physiol 263:E210 –E213. Spratt DI, Longcope C, Cox PM, Bigos ST, Wilbur-Welling C (1993): Differential changes in serum concentrations of an-drogens and estrogens (in relation with cortisol in postmeno-pausal women with acute illness). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 76:1542–1547.

Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA (1981): Depressed mood and other psychiatric manifestatiuons of Cushing’s syn-drome: Relationship to hormone levels. Psychosom Med 43:3–18. Winterer J, Gwirtsman DR, George DT, Cutler B (1985): Adrenocorticotropin-stimulated adrenal secretion in anorexia nervosa: Impaired secretion at low weight with normalization after recovery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 61:693– 697. Wolkowitz OM, Reus VI, Keebler A, Nelson N, Friedland M,

Brizendine L, Roberts E (1999): Double-blind treatment of major depression with dehydroepiandrosterone. Am J

Psychi-atry 156:646 – 649.

Wolkowitz OM, Reus VI, Roberts E (1995): Antidepressant and cognition enhancing effects of DHEA in major depression.

Ann N Y Acad Sci 774:337–339.

Wolkowitz OM, Reus VI, Roberts E, Manfredi F, Chan T, Raum WJ, et al (1997): Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): Treat-ment of depression. Biol Psychiatry 41:311–318.

Woolston JL, Gianfredi S, Gertner JM, Paugus JA, Mason JW (1983): Salivary cortisol: A non-traumatic sampling tech-nique for assaying cortisol dynamics J Am Acad Child

Psychiatry 22:474 – 476.