http://cjs.sagepub.com

Psychology

Canadian Journal of School

DOI: 10.1177/0829573507301039

2007; 22; 14 Canadian Journal of School PsychologySeverina Luciano and Robert S. Savage

Educational Settings

Bullying Risk in Children With Learning Difficulties in Inclusive

http://cjs.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/22/1/14The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of:

Canadian Association of School Psychologists

can be found at: Canadian Journal of School Psychology

Additional services and information for

http://cjs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://cjs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

Volume 22 Number 1 June 2007 14-31 © 2007 Sage Publications 10.1177/0829573507301039 http://cjsp.sagepub.com hosted at http://online.sagepub.com

Bullying Risk in Children With

Learning Difficulties in

Inclusive Educational Settings

Severina LucianoRobert S. Savage McGill University

Abstract: This study investigated whether students with learning difficulties (LDs) attending inclusive schools that eschewed segregated “pull out” programs reported more incidents of being bullied than their peers without LDs. Cognitive and self-perception factors associated with reports of peer victimization were also explored. Participants were 13 Grade 5 students with LDs and 14 classmates without LDs, matched on gender. Results showed that students with LDs self-reported significantly more incidents of being bullied than students without LDs. After statistical controls for group differences in receptive vocabulary, differences in bullying were no longer sig-nificant. Results suggest first that children with LDs in inclusive schools that eschew pull-out programs may still experience significant bullying. Second, the link between LDs, peer rejection, and victimization may reflect the social impact of language diffi-culties. Implications for reducing peer victimization in inclusive settings are discussed.

Résumé:Cette étude visait à déterminer si les élèves avec des troubles d’apprentissage (TA) inscrits dans des écoles intégratrices, soit des écoles qui évitent les programmes avec ségrégation et “isolement”, sont plus souvent victimes d’intimidation que leurs pairs avec des aptitudes d’apprentissage typiques. Cette étude examine également les facteurs cognitifs et les facteurs d’autoperception associés aux incidents déclarés de victimisation par les pairs. Treize élèves de la cinquième année avec des TA et quatorze condisciples sans TA, appariés en fonction du sexe, ont participé à cette étude. Les résultats font état d’une fréquence manifestement supérieure d’incidents autodéclarés d’intimidation parmi les élèves avec des TA que parmi les élèves sans TA. À la suite de l’application de contrôles statistiques pour tenir compte des écarts entre les groupes au niveau du vocabulaire réceptif, les écarts au niveau de l’intimidation n’étaient plus significatifs. Dans un premier temps, les résultats laissent supposer que les enfants avec des troubles d’apprentissage dans des écoles qui évitent les programmes “d’isolement” peuvent tout de même vivre d’importants problèmes d’intimidation. Dans un deuxième temps, les résultats laissent supposer que le lien entre les troubles d’apprentissage, le rejet par les pairs et la victimisation peut témoigner des répercussions sociales des

difficultés linguistiques. Cette étude aborde également les implications de la réduction de la victimisation par les pairs dans les milieux intégrés.

Keywords: bullying; inclusion; language; learning difficulties; literacy; risk

C

hildren with special learning needs have been shown to be at increased risk of being bullied by their peers at school (Hugh-Jones & Smith, 1999; Kaukiainen et al., 2002; Martlew & Hodson, 1991; Mishna, 2003; Morrison & Furlong, 1994; Nabuzoka & Smith, 1993; Norwich & Kelly, 2004; Sveinsson, 2006; Whitney, Smith, & Thompson, 1994). Studies have found that this increased risk of peer victimization is associated with deficits in social competence (Bauminger, Edelsztein, & Morash, 2005; Kaukiainen et al., 2002), academic difficulties (Singer, 2005; Whitney et al. 1994), disruptive behav-iour (Roberts & Zubrick, 1992), language impairment (Hugh-Jones & Smith, 1999; Knox & Conti-Ramsden, 2003; Savage, 2005), and low self-esteem (Kaukiainen et al., 2002). These problems have been linked to the internalizing problems associated with peer rejection, which prevents students with learning difficulties (LDs) from forming friendships that may protect them against being bullied (Chazan, Laing, & Davies, 1994; Coie & Cillessen, 1993; Geisthardt & Munsch, 1996; Hugh-Jones & Smith, 1999; Nabuzoka & Smith, 1993: Rigby, 2000; Roberts & Zubrick, 1992; Savage, 2005; Wenz-Gross & Siperstein, 1997; Whitney et al., 1994). It is important to tackle the prob-lem of bullying because of the serious long-term consequences that affect its victims. These include low self-esteem, loneliness, anxiety, and depression (Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Harter, Whitesell, & Junkin, 1998; Hugh-Jones & Smith, 1999; Kaukiainen et al., 2002; Lopez & DuBois, 2005; Neary & Joseph, 1994; Piek, Barrett, Allen, Jones, & Louise, 2005; Rigby, 2000; Smith & Brain, 2000; Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005).Bullying and/or Peer Victimization

Definition and prevalence.Bullying or victimization is a form of aggression in which a person is exposed repeatedly to negative actions. Three key characteristics of bullying are (a) an imbalance of power, in which the victim feels helpless against the attacker; (b) an aggressive act, in which there is an intent to harm; and (c) repeated, long-term exposure to such attacks (Olweus, 1994; Smith & Brain, 2000). Approximately 10% of school children report being victims of bullying (Olweus, 1995; Perry, Kusel, & Perry, 1988; Smith, Shu, & Madsen, 2001; Whitney & Smith, 1993) with an increased inci-dence of up to 83% in children with LDs (Hugh-Jones & Smith, 1999; Kaukiainen et al., 2002; Martlew & Hodson, 1991; Morrison & Furlong, 1994; Nabuzoka & Smith, 1993; Savage, 2005; Whitney et al., 1994).

Characteristics of victims and peer rejection. Research findings have been con-sistent in finding that victims of peer aggression typically display characteristics that denote internalizing problems and interpersonal attributes, which result in peer rejection (Egan & Perry, 1998; Hodges & Perry, 1999; Olweus, 1995; O’Moore & Kirkham, 2001; Solberg & Olweus, 2003). The interpersonal characteristics linked to peer rejection in students with LDs are communication difficulties (Hugh-Jones & Smith, 1999; Savage, 2005), social skills deficits (Bauminger et al., 2005; Kavale & Forness, 1996), and poor academic performance (Kavale & Forness, 1996; Roberts & Zubrick, 1992; Singer, 2005). The internalizing problems that seem to put children at risk of peer victimization have been identified as anxious disposition, insecurity, low self-esteem, submissiveness, and passivity (Chazan et al., 1994).

Internalizing problems. Students with LDs are likely to exhibit internalizing prob-lems because repeated academic failures may lead to low scholastic self-concept and learned helplessness, which may erode their overall feelings of self-worth and result in passive and submissive behaviour. In fact, several studies indicate a negative academic self-concept (Hall, Rouse, Bolen, & Mitchell, 1993; Stanovich, Jordan, & Perot, 1998) and a low sense of global self-worth (Harter et al., 1998; Kaukiainen et al., 2002; Rogers & Saklofske, 1985; Vaughn, Elbaum, Schumm, & Hughes, 1998) in students with LDs. In addition, Rogers and Saklofske (1985) found that these students reported having a more externally oriented locus of control and lower performance expecta-tions. Similarly, Hall et al. (1993) found that students with LD expressed a greater ten-dency toward an external locus of control and perceived less control over academic successes than peers without LDs. Rogers and Saklofske proposed that accumulated failure experiences lead to these negative affective characteristics, in a mutually rein-forcing manner. These internalizing problems make students with LDs especially vulnerable to peer aggression. Neary and Joseph (1994) found that victims of bullying rated themselves as lower on self-perceptions of social acceptance, behavioural conduct, and global self-worth as compared to nonvictimized students. Rudolph, Caldwell, and Conley (2005) reported that negative approval-based self-appraisals were associated with more emotional distress, particularly in victimized children. Internalizing problems associated with peer victimization have also been reported in research conducted by Nishina, Juvonen, and Witkow (2005) and Troop-Gordon and Ladd (2005).

Inclusion and Students With Special Learning Needs

and found that the students with LDs in the integrated setting did not socialize with the mainstream peers and reported being teased and bullied more often. In the current study, students with LDs were mainstreamed only for meals, playtime, and art classes. Similarly, Norwich and Kelly (2004) reported a high incidence of bullying in students with LDs irrespective of school placement. As with the previously mentioned studies, here too, some students in inclusive settings spent part of the day in resource units. Thus, none of the above-mentioned findings can answer questions about the effects of full inclusion programs on bullying.

In the current study, we seek to determine whether students with LDs attending inclusive educational settings do indeed report being bullied at a greater frequency than students without learning problems. Because links have been found between peer rejection and peer victimization, we look for correlations between self-reported victimization and attributes that might isolate students with LDs. These include fac-tors associated with internalizing problems, such as negative self-perceptions and externally oriented locus of control.

Method

Participants

The participants were 27 fifth-grade students (14 boys and 13 girls), with a mean age of 130.81 months (range 125 to 137 months). No formal data on ethnicity was collected; however, all but four students from the total sample were first-language English speakers. Participants were recruited from two Grade 5 classes in two sepa-rate multicultural elementary schools, from English-language school boards in Montreal, Canada, area suburbs. Both schools had put into action antibullying initia-tives. The school boards involved in the current study espoused the philosophy of inclusion, whereby all students are educated within the regular classroom. Thus, students with LDs spent all of their instructional time in the general classroom with their peers without LDs.

Of the total sample, 13 students (7 boys and 6 girls) were identified as having LDS; 9 children from School A, and 4 from School B. Of the 9 students from School A, 4 had received official codes as being at risk for LDs. The rest of the sample of students with LDs were identified by their teachers via criterion-referenced tests. None of the students with LDs had received resource support services during the current academic year. The control group consisted of 14 children without LDs (7 boys and 7 girls) recruited from the same classes as the students with LDs.

Procedure

obtained for all participants. Participants met with the researcher individually for a single 1-hour session. The assessment tools included measures of self-concept, locus of control, self-reports of being bullied, receptive vocabulary and/or verbal ability, and reading ability. Each data-collecting session began with a brief rapport-building conversation that was followed by a questionnaire obtaining personal information such as language spoken at home that was followed by the administration of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III (Dunn & Dunn, 1997). This assessment tool was always given first because it is believed to promote feelings of success. The adminis-tration order of the remainder of the assessment tools was counterbalanced using a Latin-square design. To avoid confounding effects related to varying reading and cog-nitive abilities, all questions and responses were read by the researcher to all partici-pants, experimental and control groups alike. Teachers were asked to complete a brief checklist that looked at their use of a variety of classroom strategies to determine if the teaching styles of the four teachers varied significantly. Specifically, strategies that promote self-determination and self-efficacy, such as goal setting, self-regulation, and choice making (Wehmeyer & Schalock, 2001), were interspersed among other typical teaching methods.

Assessment Tools

Self-concept. Harter’s (1985) Self-Perception Profile for Children was used to assess children’s domain-specific judgments of their competence and feelings of self-adequacy and a global perception of their worth or esteem as a person. The domain-specific self-perceptions include scholastic competence, social acceptance, athletic competence, physical appearance, and behavioural conduct, and global self-worth. High scores indicate positive self-perceptions, whereas low scores suggest negative self-judgments.

Locus of control.The Nowicki-Strickland Locus of Control Scale for Children (Nowicki & Strickland, 1973) is a measure of generalized locus of control for children and adolescents. The task consists of 40 questions describing reinforcement situations across interpersonal and motivational areas such as relationships, achieve-ment, and dependency. For the age group studied in the current project, an abbrevi-ated version was used that consisted of 19 questions. The resulting score is based on the number of items answered in an external direction, whereby the higher the score, the more external the individual’s orientation. There is no cut-off point that desig-nates a person’s locus of control as internal or external. Rather, the scores can be used to compare individuals in their tendency to be more or less internally or exter-nally oriented than others (Mamlin, Harris, & Case, 2001).

occurred during the previous week in school. The authors maintain that asking students to report on incidents that occurred recently helps to avoid imprecise responses because of inaccurate recollections. The authors recommend that any key items ticked as “more than once” indicate that the child is at risk of being bullied. In a recent study on prevalence estimates of bullying, Solberg and Olweus (2003) found that a cut-off point of 2 to 3 times per month effectively distinguished students that were involved versus those that were not involved in bullying. Therefore in the cur-rent study, key items that were ticked as “once” or “more than once per week” were combined to identify self-reported victims of bullying.

Receptive vocabulary and English language ability.The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—III (Dunn & Dunn, 1997) was used to assess receptive vocabulary achieve-ment in the English language. It is a norm-referenced test that is designed to mea-sure receptive vocabulary attainment for standard English and screen for verbal ability and language development.

Reading ability. The Woodcock Johnson III Tests of Achievement (WJIII) Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001) is a norm-referenced assessment tool designed to measure the cognitive abilities, skills, and academic knowledge customarily found in school. Four tests within the WJIII were used to assess reading ability: Letter-Word Identification, Reading Fluency, Passage Comprehension, and Word Attack.

Results

Four sets of statistical analyses were conducted to evaluate the relationship between learning difficulties, self-reports of bullying, and cognitive and self-perception vari-ables. The first results presented describe the mean values and standard deviations of the receptive vocabulary, reading, and self-perception variables for the two groups of students, those with and without LD, as well as the differences between these groups. Next, these factors were reanalyzed, controlling separately for receptive vocabulary and reading ability, and presented as above. Finally, correlations between reports of being bullied and receptive vocabulary, reading ability, and self-perceptions are presented.

Prior to comparing group differences, descriptive statistics were calculated to ensure normal distribution of performance on all assessment tasks. Results from the Reading Fluency task of the WJIII demonstrated a skewed distribution (positive kur-tosis, k= 6.27). This measure was transformed using the log 10 function recom-mended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2001). This improved the data distribution substantially. Analysis of gender differences were also computed prior to comparing students with and without LD. Although girls ticked fewer items indicative of bully-ing experiences, with mean scores for girls bebully-ing 1.77 (SD=2.74) and 2.71 (SD=

these analyses, the two classrooms were compared in relation to teaching approaches that empower students, to control for this possible confound. The data obtained from the checklists on classroom strategies that were completed by the teachers involved in the study showed that they did not differ significantly,F(1, 4) =3.87,ns.Thus, it

was possible to combine the results of all students from both classrooms to form two groups, students with LDs and students without LDs, for all statistical analyses.

Simple Group Differences

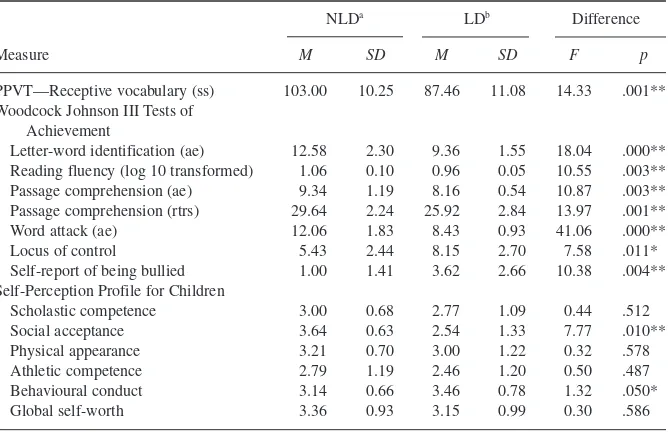

Data for all children were submitted to a series of ANOVAs with reader type (LDs vs. non-LDs) as the between-participants variable, and the literacy and cognitive measures as the respective dependent variables. These showed that students with LDs significantly differed from their peers in cognitive measures regarding vocabu-lary and reading ability. Differences in measures of receptive vocabuvocabu-lary were statistically significant, F(1, 25) = 14.33, p = .001. There were also significant

differences in all of the measures of reading ability: letter-word identification,

F(1, 25) =18.04,p<.001; reading fluency,F(1, 25) =10.55,p=.003; passage

com-prehension,F(1, 25) =10.87, p =.003, and word attack,F(1, 25) =41.06,p<.001.

In addition, performance on the modified Passage Comprehension task also showed significant statistical differences between the two groups,F(1, 24) =13.97,p=.001.

This task had been adapted to ensure that deficits in reading comprehension in students with LDs were related to comprehension difficulties rather than decoding problems. These results suggest that we have indeed identified two groups of children, one with broadly average reading abilities and another with broadly below-average reading abilities. These analyses also show, however, the presence of a broader language problem in the sample of children with LDs.

The first goal of the current project was to determine if when attending inclusive schools that eschewed “pull-out” approaches, children with LDs report more inci-dents of being bullied than stuinci-dents without LDs. The figures in Table 1 demonstrate that in the current sample of students, those with LDs do indeed report being bullied more than their peers without LDs. The group main effect reached significance for bullying,F(1, 25) =10.38,p<.01.

Although the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III could also be used as a screen-ing test for verbal abilities, the results in the current study could not confirm this because 4 of the participants are not first-language English speakers, and the lan-guage spoken at home is other than English. The authors of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III specified that their test could be used as a screen for verbal abil-ity only when English was the language of the examinees’ home, communabil-ity, and school (Dunn & Dunn, 1997). When the scores of the 4 nonnative English speaking students were excluded from the data set, analysis still demonstrated that the students with LDs differed significantly on verbal ability,F(1, 21) =14.19,p=.001.

measures that include locus of control and Harter’s self-concept scores as the respective dependent variables. Students with LDs reported significantly higher locus-of-control scores than their peers without LDs,F(1, 25) =7.58,p=.011, demonstrating a more

external sense of control over their lives. Only one of Harter’s self-perception measures resulted in a significant statistical difference between the two groups. More students with LDs reported that not having very many friends was really true for them on the Self-Perception Profile for Children,F(1, 25) =7.77,p=.010.

Group Differences When Controlling for Receptive Vocabulary Scores

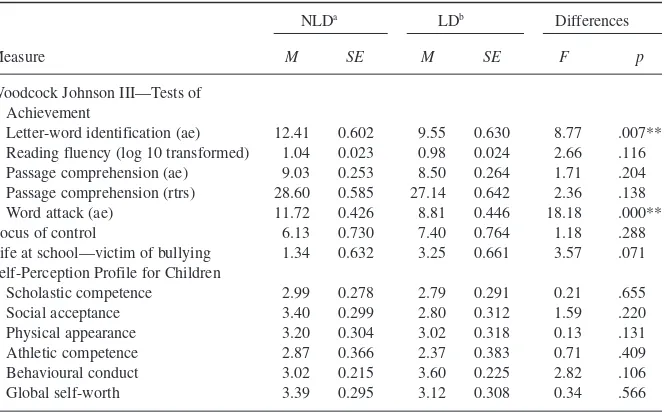

The second phase of analysis considered the occurrence of group differences when receptive vocabulary was statistically controlled using ANCOVA to identify the source of the effects. Data for all children were submitted to a series of univariate

Table 1

Means and Standard Deviations of Cognitive and Self-Perception Variables per Group, With Difference and Significance Between Groups

NLDa LDb Difference

Measure M SD M SD F p

PPVT—Receptive vocabulary (ss) 103.00 10.25 87.46 11.08 14.33 .001** Woodcock Johnson III Tests of

Achievement

Letter-word identification (ae) 12.58 2.30 9.36 1.55 18.04 .000** Reading fluency (log 10 transformed) 1.06 0.10 0.96 0.05 10.55 .003** Passage comprehension (ae) 9.34 1.19 8.16 0.54 10.87 .003** Passage comprehension (rtrs) 29.64 2.24 25.92 2.84 13.97 .001** Word attack (ae) 12.06 1.83 8.43 0.93 41.06 .000** Locus of control 5.43 2.44 8.15 2.70 7.58 .011* Self-report of being bullied 1.00 1.41 3.62 2.66 10.38 .004** Self-Perception Profile for Children

Scholastic competence 3.00 0.68 2.77 1.09 0.44 .512 Social acceptance 3.64 0.63 2.54 1.33 7.77 .010** Physical appearance 3.21 0.70 3.00 1.22 0.32 .578 Athletic competence 2.79 1.19 2.46 1.20 0.50 .487 Behavioural conduct 3.14 0.66 3.46 0.78 1.32 .050* Global self-worth 3.36 0.93 3.15 0.99 0.30 .586

Note: PPVT = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III; NLD = children without learning difficulties; LDs = children with learning difficulties; ss = standard score; ae = age equivalent; passage comprehension (rtrs) = passage comprehension when read to, using raw score.

ANCOVAs with reader type (LDs vs. non-LDs) as the between-participants variable, and the literacy and cognitive measures as the respective dependent variables, and with receptive vocabulary as the covariate. Table 2 shows mean scores and group dif-ferences in the reading-ability variables, self-reports of bullying, locus of control, and self-perception variables when controlling for receptive vocabulary scores.

Between-group differences are significantly reduced for all measured variables. When controlling for receptive vocabulary skill, students in the two groups do not differ in their self-reports of being bullied. The only measures that show any signif-icant difference between groups even when controlled for receptive vocabulary are the reading dimensions: Letter-Word Identification task,F(1, 24) =8.77,p=.007,

and the Word Attack task,F(1, 24) =18.18,p< .001, of the WJIII. Regardless of

their lower vocabulary scores, the current sample of students with LDs differs sig-nificantly from their peers without LDs in decoding and word recognition skills. It is important to note that the lack of significant differences between the two groups in regards to self-reports of being bullied, when receptive vocabulary attainment is controlled for, suggests that the language problems experienced by the students with LDs is a major contributing factor to their reports of peer victimization and a more external locus of control.

Group Differences When Controlling for Reading Scores

A third set of analysis looked at the occurrence of group differences when read-ing ability was covaried with the presence of LDs. Data for all children were sub-mitted to a series of univariate ANCOVAs with reader type (LDs vs. non-LDs) as the between-participants variable, and the literacy and cognitive measures as the respec-tive dependent variables, and with the letter-word identification reading ability score as the covariate. The differences between students with LDs and learners without LDs on several measures, when controlling for reading ability, are similar to those following the straightforward analyses. Students with LDs still reported significantly higher rates of being bullied,F(1, 24) =4.57,p=.043. They also scored significantly

higher on the locus-of-control measure, F(1, 24) =7.68,p=.011, and lower on social

acceptance self-perceptions,F(1, 24) =7.39,p=.012.

Receptive vocabulary scores are still significantly lower for students with LDs,

F(1, 24) =5.91,p=.023. The related reading measure of decoding skills, the

Word-Attack task of the WJIII, also results in significantly lower scores for students with LDs,F(1, 24) =12.96,p=.001. In addition, the adapted passage comprehension task

in which passages were read to participants demonstrated significantly lower raw scores for the group with LDs,F(1, 23) =5.71,p=.025. Although these analyses

Correlational Analysis

The second objective of the current study was to report on factors that are associ-ated with increased reports of being bullied. In the last phase of data analysis, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to identify relationships between self-reports of being bullied and cognitive and self-perception variables. Table 3 summarizes these correlations. Self-reports of being bullied are negatively correlated with receptive vocabulary attainment,r=–.481,p= .011. This value was recalculated excluding the

results from the four participants who are not first-language English speakers to assess whether a similar relationship could be found for verbal ability. There is a significant relationship between verbal ability and self-reports of being bullied,r =–.548,p=

.007, suggesting that students with lower verbal abilities report more peer victimiza-tion than students with better language skills. The social acceptance dimension of Harter’s Self-Perception Profile for Children demonstrated a negative correlation with self-reports of being bullied,r=.077,p=.044. Children who perceived themselves as

Table 2

Adjusted Means and Standard Errors of Cognitive and Self-Perception Variables per Group, When Covarying Receptive Vocabulary,

With Difference and Significance Between Groups

NLDa LDb Differences

Measure M SE M SE F p

Woodcock Johnson III—Tests of Achievement

Letter-word identification (ae) 12.41 0.602 9.55 0.630 8.77 .007** Reading fluency (log 10 transformed) 1.04 0.023 0.98 0.024 2.66 .116 Passage comprehension (ae) 9.03 0.253 8.50 0.264 1.71 .204 Passage comprehension (rtrs) 28.60 0.585 27.14 0.642 2.36 .138 Word attack (ae) 11.72 0.426 8.81 0.446 18.18 .000** Locus of control 6.13 0.730 7.40 0.764 1.18 .288 Life at school—victim of bullying 1.34 0.632 3.25 0.661 3.57 .071 Self-Perception Profile for Children

Scholastic competence 2.99 0.278 2.79 0.291 0.21 .655 Social acceptance 3.40 0.299 2.80 0.312 1.59 .220 Physical appearance 3.20 0.304 3.02 0.318 0.13 .131 Athletic competence 2.87 0.366 2.37 0.383 0.71 .409 Behavioural conduct 3.02 0.215 3.60 0.225 2.82 .106 Global self-worth 3.39 0.295 3.12 0.308 0.34 .566

Note: NLD = children without learning difficulties; LDs = children with learning difficulties; ss = stan-dard score; ae = age equivalent; passage comprehension (rtrs) = passage comprehension when read to, using raw score.

25

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

1. Bullied –.481*

2. Vocabulary –.548**a

3. LWI –.406* .469*

4. RF –.406* .555** .702**

5. PC –.515** .655** .596** .748**

6. PC (read to) –.491* .772** .480* .617** .808**

7. WA –.442* .639** .846** .800** .668** .678**

8. LOC .554** –.562** –.174 –.267 –.220 –.415* –.350

9. SC-scholastic –.021 .097 .003 .035 .049 –.002 .048 –.147

10. SC-social –.390* .527** .192 .175 .278 .303 .270 –.570** .311

11. SC-physical –.077 .089 –.244 –.436* –.224 –.116 –.180 –.181 .103 .467*

12. SC-athletic –.019 .008 .201 .054 –.143 –.051 .106 –.063 .325 .144 –.097

13. SC-conduct –.390* .056 –.494** –.246 .029 –.007 –.355 –.146 .232 .051 .170 –.226

14. SC-global .086 .026 –.057 –.106 –.371 –.223 .065 –.272 .026 .219 .553** –.049 –.117

Note: LWI =letter-word identification; RF =reading fluency; PC =passage comprehension; WA =word attack; LOC =locus of control; SC =self-concept. a. This correlational value excludes participants who are not first-language English speakers.

*p<.05, two-tailed. **p<.01, two-tailed.

by Siti alvimahtin on November 9, 2008

http://cjs.sagepub.com

having fewer friends reported being bullied more often than children who felt they had many friends. Locus-of-control scores are positively correlated with self-reports of being bullied,r=.554,p=.003. This indicates that the more children are externally oriented, the greater the degree or frequency they report being bullied. Finally, all of the reading-ability measures from the WJIII are negatively correlated with self-reports of being bullied: Letter-Word Identification,r= −.406,p=.035; Reading Fluency,r=

–.406,p=.036; Passage Comprehension,r=–.515,p=.006; Passage Comprehension (when read to),r=–.491,p=.011; and Word Attack,r=–.442,p=.003. This sug-gests that students with widespread reading difficulties report being bullied to a greater extent than students with age-appropriate reading abilities.

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to determine whether children with LDs reported being bullied at a greater frequency than their peers without LDs when attend-ing inclusive educational settattend-ings characterized by the absence of pull-out classes. A secondary goal was to report on the cognitive and self-perceptual factors that are asso-ciated with reports of peer victimization. The major findings of the current research project demonstrate that in general classrooms children with LDs reported more inci-dents of being bullied than stuinci-dents without LDs and that receptive vocabulary attain-ment and (to a lesser degree) reading skills, locus of control, and self-perceptions of social acceptance were associated with self-reported victimization scores.

Proponents of inclusion maintain that integrated educational settings provide students with LDs opportunities for socialization that they would otherwise lack in segregated settings (Stainback et al., 1996). Because the participants in the current study did not spend any class time separated from their peers without LDs, it would be expected that their educational environment would not limit their opportunities for socialization. Also, because the students are not openly categorized as having LDs, they do not carry labels that are believed to stigmatize and result in peer rejec-tion (Stainback et al., 1996). Thus, considering that there is a significant difference in self-reports of being bullied between the two groups of students, these global fea-tures of the educational placement clearly do not of themselves guarantee that children with LDs will not report bullying.

correlated negatively with self-reports of being bullied. Thus, it is feasible to surmise that the bullied students in the current sample had been rejected by their peers.

The following factors have been identified in prior research as leading to peer rejection: low academic performance, communication and/or language difficulties, and poor social skills (Coie & Cillessen, 1993; Hugh-Jones & Smith, 1999; Roberts & Zubrick, 1992). Data regarding social skills were not collected in the current pro-ject. However, poor academic performance and communication difficulties can be inferred from the low scores on the reading-ability measures and test of verbal abil-ity. These two correlates of victimization may have resulted in social isolation that made students with LDs vulnerable to peer aggression.

Receptive vocabulary attainment was the variable that was consistently negatively correlated with increased self-reported incidents of being bullied. This relationship was evident across all statistical analyses. The fact that the group differences in vic-timization scores disappeared when controlling for receptive vocabulary attainment indicates that this variable plays a key role in the reports of bullying in the current sample of students. The receptive vocabulary measure is reported by the authors of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III to be a good screen for verbal ability. The adapted passage comprehension test of the WJIII, which is believed to be related to verbal abilities, also showed lower scores for students with LDs. In addition, these results were negatively correlated with self-reports of being bullied.

It is possible that students with language problems are targeted for bullying because this deficit may lead to peer rejection through affected students’ misinterpre-tation of social situations (Bauminger et al., 2005; Kaukiainen et al., 2002; Nabuzoka & Smith, 1993). Communication difficulties may also contribute to decreased social acceptance and subsequent peer aggression because these problems make students stand out from their peers (Owens, Shute, & Slee, 2000). Furthermore, decreased ver-bal abilities may interfere with children’s ability to respond to verver-bal assaults effec-tively (Savage, 2005).

Previous research has also suggested that a major characteristic of victims of peer aggression consists of internalizing problems, such as anxiety, low self-esteem, and unassertiveness (Hodges & Perry, 1999). Individuals with an external locus of con-trol are likely to exhibit passive and submissive behaviours that would make them vulnerable to peer aggression. These internalizing behaviours may be related to learned helplessness and external locus of control secondary to repeated failures and communication difficulties (Hall et al., 1993; Rogers & Saklofske, 1985). Children who are passive, submissive, and exhibit low self-esteem are potential targets for bullies because they are perceived as weak and unlikely to retaliate.

that make them vulnerable to peer rejection and subsequently to peer victimization. Low academic performance, language difficulties, and unassertiveness make these children less liked by their peers without LDs. Thus, the issue seems to lie in how to promote friendships that would provide at-risk students with the protection that would dissuade aggressors from victimizing them.

This investigation has several limitations that should be noted. First, this was a convenience sample so the small number of participants may make the findings less generalizable. Nonetheless, the results were robust statistically speaking and did replicate several existing works in regards to characteristics of victims of bullying. Still, the effect would need to be reproduced in a larger sample for greater confidence to be attached to the findings. Second, although a matched control group was used to compare differences between students with and without LDs, various educational set-tings were not compared. Finally, the validity of self-reports of peer victimization has often been questioned because it has been found to be inconsistent with peer reports (Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Perry et al., 1988).

Future directions could entail conducting similar investigations with a larger sam-ple of students. It would be advantageous to compare a variety of settings or learning situations, such as special schools, resource rooms, or resource services within the general education classroom. Measures of social acceptance would contribute greatly to understanding the social dynamics of students with special learning needs in inclu-sive settings. Also, peer reports and observational data would validate self-reported data. Related to social dynamics are the social skills of students with LDs. It would be valuable to learn if inclusive settings enhance the acquisition of social skills via greater exposure to peers without LDs.

References

Bauminger, N., Edelsztein, H. S., & Morash, J. (2005). Social information processing and emotional understanding in children with LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(1), 45-61.

Boulton, M. J., Trueman, M., Chau, C., Whitehand, C., & Amatya, K. (1999). Concurrent and longitudi-nal links between friendship and peer victimization: Implications for befriending interventions. Journal of Adolescence, 22,461-466.

Chazan, M., Laing, A. F., & Davies, D. (1994). Bullies and victims. In Emotional and behavioural diffi-culties in middle childhood (pp. 154-171). London: The Falmer Press.

Coie, J. D., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (1993). Peer rejection: Origins and effects on children’s development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2(3), 89-92.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test(3rd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Egan, S. K., & Perry, D. G. (1998). Does low self-regard invite victimization? Developmental Psychology, 34(2), 299-309.

Geisthardt, C., & Munsch, J. (1996). Coping with school stress: A comparison of adolescents with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29(3), 287-296.

Hall, C. W., Rouse, B. D., Bolen, L. M., & Mitchell, C. C. (1993, April). Social-emotional factors in students with and without learning disabilities. Paper presented at the annual convention of the National Association of School Psychologists, Washington, DC.

Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children. Denver, CO: University of Denver. Harter, S., Whitesell, N. R., & Junkin, L. J. (1998). Similarities and differences in domain-specific and global self-evaluations of learning-disabled, behaviorally disordered, and normally achieving adoles-cents. American Educational Research Journal, 35(4), 653-680.

Hodges, E. V. E., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., & Bukowski, W. M. (1999). The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 94-101. Hodges, E. V. E., & Perry, D. G. (1999). Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of

vic-timization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(4), 677-685.

Hugh-Jones, S., & Smith, P. K. (1999). Self-reports of short- and long-term effects of bullying on children who stammer. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 69(2), 141-158.

Kaukiainen, A., Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Tamminen, M., Vauras, M., Maki, H., et al. (2002). Learning difficulties, social intelligence, and self-concept: Connections to bully-victim problems. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43,269-278.

Kavale, K. A., & Forness, S. R. (1996). Social skill deficits and learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29(3), 226-237.

Klingner, J. K., Vaughn, S., Schumm, J. S., Cohen, P., & Forgan, J. W. (1998). Inclusion or pull-out: Which do students prefer? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 31(2), 148-158.

Knox, E., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2003). Bullying risks of 11-year-old children with specific language impairment (SLI): Does school placement matter? International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 38(1), 1-12.

Lopez, C., & DuBois, D. L. (2005). Peer victimization and rejection: Investigation of an integrative model of effects on emotional behavioural, and academic adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 25-36.

Mamlin, N., Harris, K. R., & Case, L. P. (2001). A methodological analysis of research on locus of control and learning disabilities: Rethinking a common assumption. Journal of Special Education, 34(4), 214-225. Martlew, M., & Hodson, J. (1991). Children with mild learning difficulties in an integrated and in a

special school: Comparisons of behaviour, teasing and teachers’ attitudes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 61,355-372.

Mishna, F. (2003). Learning disabilities and bullying: Double jeopardy. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 36(4), 336-347.

Morrison, G. M., & Furlong, M. J. (1994). Factors associated with the experience of school violence among general education, leadership class, opportunity class, and special day class pupils. Education and Treatment of Children, 17(3), 356-370.

Nabuzoka, D., & Smith, P. K. (1993). Sociometric status and social behaviour of children with and with-out learning difficulties. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(8), 1435-1448.

Neary, A., & Joseph, S. (1994). Peer victimization and its relationship to self-concept and depression among schoolgirls. Personal and Individual Differences, 16(1), 183-186.

Nishina, A., Juvonen, J., & Witkow, M. R. (2005). Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will make me feel sick: The psychosocial, somatic, and scholastic consequences of peer harassment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 37-48.

Norwich, B., & Kelly, N. (2004). Pupils’ views on inclusion: Moderate learning difficulties and bullying in mainstream and special schools. British Educational Research Journal, 30(1), 43-65.

Nowicki, S., Jr., & Strickland, B. R. (1973). A locus of control scale for children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 40(1), 148-154.

Olweus, D. (1994). Annotation: Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(7), 1171-1190.

O’Moore, M., & Kirkham, C. (2001). Self-esteem and its relationship to bullying behaviour. Aggressive Behavior, 27,269-283.

Owens, L., Shute, R., & Slee, P. (2000). Guess what I just heard?: Indirect aggression among teenage girls in Australia. Aggressive Behavior, 26,67-83.

Perry, D. G., Kusel, S. J., & Perry, L. C. (1988). Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology, 24(6), 807-814.

Piek, J. P., Barrett, N. C., Allen, L. S. R., Jones, A., & Louise, M. (2005). The relationship between bullying and self-worth in children with movement coordination problems. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75,453-463.

Rigby, K. (2000). Effects of peer victimization in schools and perceived social support on adolescent well-being. Journal of Adolescence, 23,57-68.

Roberts, C., & Zubrick, S. (1992). Factors influencing the social status of children with mild academic disabilities in regular classrooms. Exceptional Children, 59(3), 192-202.

Rogers, H., & Saklofske, D. H. (1985). Self-concepts, locus of control and performance expectations of learning disabled children. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 18(5), 273-278.

Rudolf, K. D., Caldwell, M. S., & Conley, C. S. (2005). Need for approval and children’s well-being. Child Development, 76(2), 309-323.

Savage, R. S. (2005). Friendship and bullying patterns in children attending a language base in a mainstream school. Educational Psychology in Practice, 21(1), 23-36.

Sharp, S., & Smith, P. K. (1994). Understanding bullying. In S. Sharp & P. K. Smith (Eds.),Tackling bullying in your school: A practical handbook for teachers(pp. 1-5). London: Routledge.

Singer, E. (2005). The strategies adopted by Dutch children with dyslexia to maintain their self-esteem when teased at school. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(5), 411-423.

Smith, P. K., & Brain, P. (2000). Bullying in schools: Lessons from two decades of research. Aggressive Behavior, 26,1-9.

Smith, P. K., Shu, S., & Madsen, K. (2001). Characteristics of victims of school bullying: Developmental changes in coping strategies. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.),Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized(pp. 332-351). New York: Guilford.

Solberg, M. E., & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behaviour, 29,239-268.

Stainback, S., Stainback, W., & Ayres, B. (1996). Schools as inclusive communities. In W. Stainback & S. Stainback (Eds.),Controversial issues confronting special education: Divergent perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 31-43). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Stanovich, P. J., Jordan, A., & Perot, J. (1998). Relative differences in academic self-concept and peer acceptance among students in inclusive classrooms. Remedial and Special Education, 19(2), 120-126. Sveinsson, A. V. (2006). School bullying and disability in Hispanic youth: Are special education students at greater risk of victimization by school bullies than non-special education students? Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 66(9A), 3214.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics.Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Troop-Gordon, W., & Ladd, G. W. (2005). Trajectories of peer victimization and perceptions of the self

and schoolmates: Precursors to internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development, 76(5), 1072-1091.

Vaughn, S., Elbaum, B. E., Schumm, J. S., & Hughes, M. T. (1998). Social outcomes for students with and without learning disabilities in inclusive classrooms. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 31(5), 428-436. Vaughn, S., & Klingner, J. K. (1998). Students’ perceptions of inclusion and resource room settings.

Journal of Special Education, 32(2), 79-88.

Wehmeyer, M. L., & Schalock, R. L. (2001). Self-determination and quality of life: Implications for special education services and supports. Focus on Exceptional Children, 33(8), 1-17.

Whitney, I., & Smith, P. K. (1993). A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Educational Research, 35(1), 3-25.

Whitney, I., Smith, P. K., & Thompson, D. (1994). Bullying and children with special educational needs. In P. K. Smith & S. Sharp (Eds.),School bullying: Insights and perspectives(pp. 213-240). London: Routledge.

Woodcock, R. W., McGrew, K. S., & Mather, N. (2001). Woodcock Johnson III Tests of Achievement. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Severina Lucianois a resource teacher with a master’s degree in inclusive education from McGill University. She obtained her BA from Concordia University, and BEd from the University of Ottawa. She works at an inner-city high school where she provides remedial reading instruction to students with learn-ing disabilities, as well as second language learners. She also works within a multidisciplinary team as the coordinator of individual education plans. Prior to becoming a teacher, she worked as a respiratory therapist at the McGill University Health Centre. There she was involved in numerous research projects regarding pediatric and adult sleep apnea.