II

After infancy, children experience signifi cant developmental progress that isfundamentally tied to the evolution and establishment of eating behavior. In contrast to infancy, however, the period from 1 year of age to puberty is a slower period of physical growth. Birth weight triples during the fi rst year of life but does not quadruple until 2 years of age; birth length increases by 50% during the fi rst year but does not double until 4 years of age. Although growth patterns vary in individual children, from 2 years to puberty, chil-dren gain an average of 2 to 3 kg (4.5–6.5 lb) and grow in height 5 to 8 cm (2.5–3.5 in) per year. As growth rates decrease during the preschool years, appetites decrease and food intake may appear erratic and unpredictable. Parental confusion and concern are not uncommon. Frequently expressed concerns include the limited variety of foods ingested, dawdling and dis-tractibility, limited consumption of vegetables and meats, and a desire for too many sweets. Parental concern regarding children’s eating behaviors, whether warranted or unfounded, should be addressed with developmen-tally appropriate nutrition information. Anticipatory guidance for parents and caregivers is key to preventing many feeding problems.

An important goal of early childhood nutrition is to ensure children’s cur-rent and future health by fostering the development of healthy eating behav-iors. Caregivers are called on to offer foods at developmentally appropriate moments—matching the child’s age and stage of development with his or her nutrition needs. Appropriate limits for children’s eating are set by adhering to a division of responsibility in child feeding.1 Caregivers are responsible for

providing a variety of nutritious foods, defi ning the structure and timing of meals, and creating a mealtime environment that facilitates eating and social exchange. Children are responsible for participating in choices about food selection and determining how much is consumed at each eating occasion.

Toddlerhood

is generally capable of self-feeding fi rmer table foods and drinking from a “sippy” cup without help.2 Weaning from the bottle should occur at the

be-ginning of toddlerhood (12–15 months of age), and bedtime bottles should be particularly discouraged because of their association with dental caries, as should bottles containing juice at any time of the day.2 Between the fi rst

and second year, infants move from gross motor skills required for holding a spoon to developing fi ne motor skills needed to scoop food, dip food, and bring the spoon to the mouth with limited spilling.1,2 Supporting self-feeding

is thought to encourage the maintenance of self-regulation of energy intake and the mastery of feeding skills. Given earlier opportunities for mastery of self-feeding skills, the older toddler (2 years of age) is ready to consume most of the same foods offered to the rest of the family, with some extra preparation to prevent choking and gagging.

Toddlers are continually engaged in understanding the cause-and-effect relationship. In the eating domain, this translates into using utensils to move foods and using food and eating to elicit responses from the parent. These interactions are part of children’s learning about the family’s and culture’s standards for behavior; children as young as 2 years of age have demonstrat-ed the ability to evaluate their actions according to its badness or goodness in relation to parental standards for behavior.3 An example of this type of

learning is the toddler’s response of “uh-oh” to dropping food or drink on the fl oor. Toddlers seek attention and will fi nd ways, positive or negative, to engage the notice of parents. Helping parents focus on children’s positive eating behaviors rather than on food refusals or negative conduct, will keep mealtime pleasant and productive.

Preventing Choking

meal-II

music, and activities. Eating in the car should be discouraged, because: 1)aiding the child quickly is diffi cult if the only adult present is driving; and 2) with obesity prevention in mind, eating should not be encouraged in envi-ronments that are not related to family meals (in cars, in front of television/ computers, etc). Finally, analgesics used to numb the gums during teething may anesthetize the posterior pharynx; children who receive such medica-tions should be carefully observed during feeding.

Food Acceptance

Preferences for the taste of sweet have been observed shortly after birth,4

and young children show the capacity to readily form preferences for the fl avors of energy-rich foods.5 Acceptance of other foods, however, is not

immediate and may occur only after 8 to 10 exposures to those foods in a noncoercive manner.6–8 The fi ndings of one study indicate that many parents

are not aware of the lengthy but normal course of food acceptance in young children; approximately 25% of mothers with toddlers reported offering new foods only 1 or 2 times before deciding whether the child liked it, and approximately half made similar judgments after serving new foods 3 to 5 times.9 Touching, smelling, and playing with new foods as well as

put-ting them in the mouth and spitput-ting them back out are normal exploratory behaviors that precede acceptance and even willingness to taste and swal-low foods.10 Beginning around 2 years of age, children become

character-istically resistant to consuming new foods, and sometimes dietary variety diminishes to 4 or 5 well-accepted favorites. In a study of 3022 infants and toddlers ranging from 6 to 24 months of age, half of mothers with 19- to 24-month-old toddlers reported picky eating, whereas only 19% reported picky eating among 4- to 6-month-old infants.9 It should be stressed to

fami-lies that children’s failure to immediately accept new foods is a normal stage of child development that, although potentially frustrating, can be dealt with effectively with knowledge, consistency, and patience.

Although toddlers are in a generally explorative phase, they can go on food “jags,” during which certain foods are preferentially consumed to the exclusion of others.11,12 Parents who become concerned when a “good eater”

in infancy becomes a “fair to poor” eater as a toddler should be reassured that this change in acceptance is developmentally typical.

Preschoolers

their interest in eating may be unpredictable, with characteristic periods of disinterest in food. Their attention span may limit the amount of time that they can spend in the mealtime setting; however, they should be encour-aged to attend and partake in family meals for reasonable periods of time (15–20 minutes)—whether they choose to eat or not.

As children move from toddlerhood to the preschool years, they become increasingly aware of the environment in which eating occurs, particularly the social aspects of eating. By interacting with and observing other children and adults, preschool-aged children become more aware of when and where eating takes place, what types of foods are consumed at specifi c eating oc-casions (ie, ice cream is a dessert food), and how much of those foods are consumed at each eating occasion (ie, “fi nish your vegetables”). As a con-sequence of this increased awareness, children’s food selection and intake patterns are infl uenced by a variety of environmental cues, including the time of day13; portion size14–16; controlling child feeding practices, including

restriction and pressure to eat17,18; and the preferences and eating behaviors

of others.19–21

During the preschool period, most children have moved from eating on demand to a more adult-like eating pattern, consuming 3 meals each day as well as several smaller snacks. Although children’s intake from meal to meal may appear to be erratic, total daily energy intake remains fairly constant.22

Children show the ability to respond to the energy content of foods by adjusting their intake to refl ect the energy density of the diet.17,23 In contrast

to their skills in regulation of food intake, young children do not appear to have the innate ability to choose a well-balanced diet.11,12 Rather, they

depend on adults to offer them a variety of nutritious and developmentally appropriate foods and to model the consumption of those foods.

School-Aged Children

During the school years, increases in memory and logic abilities are accom-panied by reading, writing, and math skills and knowledge. This is the period in which basic nutrition education concepts can be successfully introduced. Emphasis should be placed on enjoying the taste of fruits and vegetables rather than to focus exclusively on their healthfulness, because young chil-dren tend to think of taste and healthfulness as mutually exclusive.24

II

body shape. An awareness of the physical self begins to emerge, andcom-parisons with social norms for weight and weight status begin to occur. Dur-ing this period, children vary greatly in weight, body shape, and growth rate, and teasing of those who fall outside the perceived norms for weight status frequently occurs. Friends and those outside the family can infl uence food attitudes and choices either benefi cially or negatively, which can affect the nutritional status of a given child. Television is another source of infl uence on young children’s eating, given that a majority of US school-aged children watch at least 2 hours of television each day.25 The more time children spend

watching television, the more likely they are to have higher energy intakes; consume greater amounts of pizza, salty snacks, and soda; and to be over-weight than children who spend less time watching television.25–29

School-aged children have more freedom over their food choices and, during the school year, eat at least 1 meal per day away from the home. Choices, such as the decision to consume school lunch or a snack bar meal, may affect dietary quality.30

Eating Patterns and Nutrient Needs

Toddlers

Toddlers eat, on average, 7 times each day, with snacks representing ap-proximately one fourth of daily energy intake. Between 15 and 24 months of age, approximately 59% of energy comes from table foods.31 Milk

con-stitutes the leading source (25%) of daily energy, macronutrients, and many vitamins and minerals, including vitamins A and D, calcium, and zinc.32

Fruit and vegetable intake is notably absent in some toddlers. Between 28% and 33% of toddlers do not consume fruit and between 18% and 20% do not consume vegetables on a given day; French fries are the vegetable most commonly consumed by toddlers.33

Preschool and School-Aged Children

Fruit and vegetable intake among preschool and school-aged children is also well below current recommendations.34,35 A majority of preschool and

school-aged children do not consume recommended amounts of fi ber; low-fi ber fruits, such as applesauce and fruit cocktail, have the greatest contribu-tions to daily fi ber intake.36 Alternatively, children’s intakes of fat,

discretion-ary fat, and added sugar are high.34,35,37 Further, low micronutrient-dense

energy intake are cakes, cookies, quick breads, or doughnuts; soft drinks; potato chips, corn chips, or popcorn; and sugars, syrup, or jams.39 More

energy-dense diets, defi ned as the amount of energy per daily amountof food and drink (g), are associated with higher energy intakes among pre-school and pre-school-aged children.40 Trends in eating patterns among children

have been attributed to an increase in the frequency of snacking, a shift to foods consumed away from home, and increasing food portion sizes.41–43

Key Eating and Activity Concerns Toddlers and Preschoolers School-Aged Children

Weaning •

Fluctuations in appetite •

Low micronutrient intake (iron and zinc) •

Beverages and foods with added sugar •

The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition recommends the following foods as excellent sources of iron in the diet of the child. Table A

Foods to Increase Iron

Selected Heme Iron Sources

Table Food Iron (mg of elemental iron)

Clams, canned, drained solids, 3 oz 23.8

Chicken liver, cooked, simmered, 3 oz 9.9

Oysters, Eastern canned, 3 oz 5.7

Beef liver, cooked, braised, 3 oz 5.6

Shrimp, cooked moist heat, 3 oz 2.6

Beef, composite of trimmed cuts, lean only, all grades, cooked, 3 oz

2.5

Sardines, Atlantic, canned in oil, drained solids with bone, 3 oz

II

Turkey, all classes, dark meat, roasted, 3 oz 2.0Lamb, domestic, composite of trimmed retail cuts, separable lean only, choice, cooked, 3 oz

1.7

Fish, tuna, light, canned in water, drained solids, 3 oz 1.3

Chicken, broiler or fryer, dark meat, roasted, 3 oz 1.1

Turkey, all classes, light meat, roasted, 3 oz 1.1

Veal, composite of trimmed cuts, lean only, cooked, 3 oz 1.0

Chicken, broiler or fryer, breast, roasted, 3 oz 0.9

Pork, composite of trimmed cuts (leg, loin, shoulder), lean only, cooked, 3 oz

0.9

Fish, salmon, pink, cooked, 3 oz 0.8

Commercial Baby Food*

Meat

Baby food, lamb, junior, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 1.2

Baby food, chicken, strained, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 1.0

Baby food, lamb, strained, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.8

Baby food, beef, junior, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.7

Baby food, beef, strained, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.7

Baby food, chicken, junior, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.7

Baby food, pork, strained, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.7

Baby food, ham, strained, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.7

Baby food, ham, junior, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.7

Baby food, turkey, junior, (2.5 oz) 0.6

Baby food, turkey, strained, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.5

Baby food, veal, strained, 1 jar (2.5 oz) 0.5

Selected Non-Heme Iron Sources

Oatmeal, instant, fortifi ed, cooked, 1/2 cup 7.0

Blackstrap molasses,† 2 tbsp 7.4

Tofu, raw, regular, 1/2 cup 6.7

Wheat germ, toasted, 1/2 cup 5.1

Ready-to-eat cereal, fortifi ed at different levels, 1 cup about 4.5 to 18

Soybeans, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, 1/2 cup 4.4

AAP

Apricots, dehydrated (low-moisture), uncooked, 1/2 cup 3.8

Sunfl ower seeds, dried, no hulls, 1/2 cup 3.7

Lentils, mature seeds, cooked, 1/2 cup 3.3

Spinach, cooked, boiled, drained, 1/2 cup 3.2

Chickpeas, mature seeds, cooked, 1/2 cup 2.4

Prunes, dehydrated (low-moisture), uncooked, 1/2 cup 2.3

Lima beans, large, mature seeds, cooked, 1/2 cup 2.2

Navy beans, mature seeds, cooked, 1/2 cup 2.2

Kidney beans, all types, mature seeds, cooked, 1/2 cup 2.0

Molasses, 2 tbsp 1.9

Pinto beans, mature seeds, cooked, 1/2 cup 1.8

Raisins, seedless, packed, 1/2 cup 1.6

Prunes, dehydrated (low-moisture), stewed, 1/2 cup 1.6

Prune juice, canned, 4 fl uid oz 1.5

Green peas, cooked, boiled, drained, 1/2 cup 1.2

Enriched white rice, long-grain, regular, cooked, 1/2 cup 1.0

Whole egg, cooked (fried or poached), 1 large egg 0.9

Enriched spaghetti, cooked, 1/2 cup 0.9

White bread, commercially prepared, 1 slice 0.9

Whole wheat bread, commercially prepared, 1 slice 0.7

Spaghetti or macaroni , whole wheat, cooked, 1/2 cup 0.7

Peanut butter, smooth style, 2 tbsp 0.6

Brown rice, medium-grain, cooked, 1/2 cup 0.5

Commercial Baby Food*

Vegetables

Baby food, green beans, junior, 1 jar (6 oz) 1.8

Baby food, peas, strained, 1 jar (3.4 oz) 0.9

Baby food, green beans, strained, 1 jar (4 oz) 0.8

Baby food, spinach, creamed, strained, 1 jar (4 oz) 0.7

Baby food, sweet potatoes, junior, 1 jar (6 oz) 0.7

II

CerealsBaby food, brown rice cereal, dry, instant, 1 tbsp 1.8

Baby food, oatmeal cereal, dry, 1 tbsp 1.6

Baby food, rice cereal, dry, 1 tbsp 1.2

Baby food, barley cereal, dry, 1 tbsp 1.1

Selected Good Vitamin C Sources

Fruits Vegetables

Citrus fruits (eg, orange, tangerine, grapefruit) Red, yellow, and green peppers

Pineapple Broccoli

Fruit juices enriched with vitamin C Tomato

Strawberries Cabbage

Cantaloupe Potato

Kiwifruit Leafy green vegetables

Raspberries Caulifl ower

Source of iron values in foods: US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20. 2007. Nutrient Data Labora-tory Home Page. Available at: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl. Accessed April 17, 2008. Note: fi gures are rounded.

* Baby food values are generally based on generic jar, not branded jar; 3 oz table food meat = 85 g; a 2.5 oz. jar of baby food = 71 g (an infant would not be expected to eat 3 oz [about the size of a deck of cards] of pureed table meat at a meal).

† Source of iron value was obtained from a manufacturer of this type of molasses (October 2007).

Table B

Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) for Iron for Children

Birth to 6 months 0.27 mg/day*

7–12 months 11 mg/day†

1–3 years 7 mg/day†

4–8 years 10 mg/day†

* Adequate Intake (AI)

† Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA)

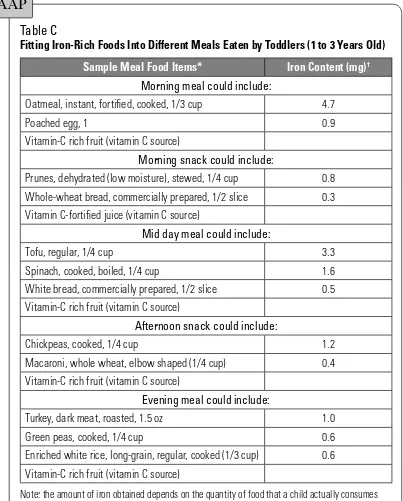

Table C

Fitting Iron-Rich Foods Into Different Meals Eaten by Toddlers (1 to 3 Years Old)

Sample Meal Food Items* Iron Content (mg)†

Morning meal could include:

Oatmeal, instant, fortifi ed, cooked, 1/3 cup 4.7

Poached egg, 1 0.9

Vitamin-C rich fruit (vitamin C source)

Morning snack could include:

Prunes, dehydrated (low moisture), stewed, 1/4 cup 0.8

Whole-wheat bread, commercially prepared, 1/2 slice 0.3

Vitamin C-fortifi ed juice (vitamin C source)

Mid day meal could include:

Tofu, regular, 1/4 cup 3.3

Spinach, cooked, boiled, 1/4 cup 1.6

White bread, commercially prepared, 1/2 slice 0.5

Vitamin-C rich fruit (vitamin C source)

Afternoon snack could include:

Chickpeas, cooked, 1/4 cup 1.2

Macaroni, whole wheat, elbow shaped (1/4 cup) 0.4

Vitamin-C rich fruit (vitamin C source)

Evening meal could include:

Turkey, dark meat, roasted, 1.5 oz 1.0

Green peas, cooked, 1/4 cup 0.6

Enriched white rice, long-grain, regular, cooked (1/3 cup) 0.6

Vitamin-C rich fruit (vitamin C source)

Note: the amount of iron obtained depends on the quantity of food that a child actually consumes and bioavailability factors (eg, foods and beverages that may be consumed that may inhibit or enhance iron absorption of any non-heme iron).

* Assume that an adequate quantity of cow milk and other foods to meet other nutrient needs are consumed.

† Figures are rounded.

AAP

II

Energy NeedsDietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) are a set of 4 nutrient-based reference values that can be used for planning and assessing diets of individuals and groups (see Appendix J).44 The DRIs include data on safety and effi cacy,

reduction of chronic degenerative disease (rather than the avoidance of nutritional defi ciency), and data on upper levels of intake (where available). The estimated average requirement (EAR) refers to the median usual intake value that is estimated to meet the requirements of one half of apparently healthy individuals of a given age and sex over time. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) refers to the level of intake that is adequate for nearly all healthy individuals of a given sex and age. When the EAR or RDA has not been established, an Adequate Intake (AI) is provided as a standard. The tolerable upper intake level (UL) is the highest level of continuing daily nutrient intake that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects in al-most all individuals. The UL, however, is not intended to be a recommend-ed level of intake. Using the age- and sex-specifi c EAR, is it possible to make a quantitative statistical assessment of the adequacy of an individual’s usual intake of a nutrient and to assess the safety of an individual’s usual intake by comparison with the UL.

Energy needs are most variable in children and depend on basal metabo-lism, rate of growth, physical activity, body size, sex, and onset of puberty (also see Chapter 13: Energy). Many nutrient requirements depend on energy needs and intake. Micronutrients that are most likely to be low or defi cient in the diets of young children are calcium, iron, zinc, vitamin B6, magnesium, and vitamin A.45,46

Supplements

Parents often ask health care professionals whether their children need vita-min supplements, and many routinely give supplements to their children, with recent estimates suggesting that 30% to 40% of children are given some kind of supplement.31 The children who receive supplements are not

1. With anorexia or an inadequate appetite or who follow fad diets. 2. With chronic disease (eg, cystic fi brosis, infl ammatory bowel disease,

hepatic disease).

3. From deprived families or who suffer parental neglect or abuse. 4. Who participate in a dietary program for managing obesity.

5. Who consume a vegetarian diet without adequate intake of dairy products. 6. With failure to thrive.

Evaluation of dietary intake should be included in any assessment of the need for supplementation. If parents wish to give their children supple-ments, a standard pediatric vitamin-mineral product containing nutrients in amounts no larger than the DRI (EAR or RDA) poses no risk. Amounts higher than the DRI should be discouraged and counseling should be provided about the toxic effects, especially of fat-soluble vitamins. Because the taste, shape, and color of most pediatric preparations are as attractive as candy, parents should be cautioned to keep them out of reach of children. (See Chapters 17–20 for more information on vitamins and minerals.)

Dietary Fat

In recent decades, emphasis and educational efforts supporting low-fat, low-cholesterol diets for the general population have increased. A variety of health organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, recommend against fat or cholesterol restriction in the fi rst 2 years of life, when rapid growth and development require high intakes of energy. For this reason, nonfat milks are not recommended for use in children younger than 2 years. For children between 12 months and 2 years of age, low-fat dairy products should be considered for children with a body mass index (BMI) at the 85th percentile or greater or a family history of obesity. Fat intake should be gradually decreased during the toddler years so that fat intake, averaged across several days, provides approximately 30% of total energy.47,48

Par-ents should be reassured that this level of intake is suffi cient for adequate growth49,50 and does not place children at increased risk of nutritional

inadequacy.37 Transitioning children’s diets to provide 30% energy from fat

II

Dietary Guidelines for AmericansIn 2005, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Department of Health and Human Services updated the Dietary Guidelines for Ameri-cans (DGAs), the federal government’s science-based advice to promote health and reduce risk of major chronic diseases through diet and physical activity.51 The DGAs can be used in developing educational programs and

materials for people 2 years and older. The DGAs promote 3 main concepts: (1) make smart choices from every food group; (2) fi nd your balance be-tween food and physical activity; and (3) get the most nutrition out of your calories.52 Overall, the DGAs encourage Americans to eat fewer calories, be

more active, and make wiser food choices. To follow the advice provided by the DGAs, parents should be encouraged to: (1) help children consume ad-equate amounts of fi ber-rich fruits and vegetables; (2) help children consume whole-grain products often, with at least half of total grains being whole grains; (3) help children 2 to 8 years of age consume 2 cups per day of fat-free or low-fat milk or equivalent milk products and help children 9 years of age and older consume 3 cups per day; (4) enable children to engage in at least 60 minutes of physical activity on most, preferably all, days of the week; (5) offer foods that help keep total fat intake between 30% and 35% of calories for children 2 to 3 years of age and between 25% and 35% of calories for children 4 to 18 years of age; (6) choose and prepare foods and beverages with little added sugars or caloric sweeteners; (7) choose and pre-pare foods for children with little salt; and (8) keep foods offered to children safe by not feeding them raw (unpasteurized) milk or any products made from unpasteurized milk; raw or partially cooked eggs or foods containing raw eggs; raw or undercooked meat, poultry, fi sh, or shellfi sh; unpasteurized juices; or raw sprouts.

MyPyramid (see Appendix K, Fig K-1) is a system of educational informa-tion and interactive tools developed by the USDA to implement the DGAs. It provides personalized food-based guidance for the public and additional resources for health care professionals.53 MyPyramid is based on both the

DGAs and the DRIs from the National Academy of Sciences, keeping in mind typical food consumption patterns of Americans. MyPyramid translates nutritional recommendations into the kinds and amounts of food to eat each day. Guidance and print materials are available on the MyPyramid Web site (www.mypyramid.gov) for children 2 years and older as well as for adults.

age. The MyPyramid for Kids symbol represents the general proportions of food from each food group and focuses on the importance of making smart food choices every day. In addition to helping parents identify the amounts that children need from each food group, the symbol and materials can be used to convey basic nutrition concepts for feeding young children, such as variety and moderation. Daily physical activity is a prominent message in MyPyramid for Kids. To support this message, Enjoy Moving, a physical ac-tivity pyramid (http://teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/enjoymovingfl yer. html; see Appendix K, Fig K-3), was developed to provide a more detailed, illustrated description of the types of physical activity in which children may engage. Children are encouraged to get at least 60 minutes of physical activity on most days and to do: plenty of moving whenever they can, more making their hearts work harder, enough stretching and building muscles, and less sitting around. Through an interactive Web-based game, lesson plans, colorful posters and fl yers, worksheets, and valuable tips for families, MyPyramid for Kids encourages children, teachers, and parents to work together to make healthier food choices and be active every day.

In addition, the USDA has developed dietary advice for Pregnant and Breastfeeding women as part of the MyPyramid Web site (http://www.my-pyramid.gov/mypyramidmoms/index.html). The interactive “MyPyramid Plan for Moms” provides personalized advice on the kinds and amounts of food to eat, taking into account the trimester of pregnancy or stage of breastfeeding. Additional information on food choices, nutritional needs, and supplements is also available on the Web site and as downloadable fact sheets.

MyPyramid was released in April 2005, and MyPyramid for Kids was re-leased in September 2005, and they replace the original Food Guide Pyramid (1992) and Food Guide Pyramid for Young Children (1998), widely recog-nized nutrition education tools.

II

Nutrition Guidelines for Children*Make available and offer a colorful variety of fruits and vegetables for children to consume •

every day.

Limit intake of foods and beverages with added sugars or salt. •

Keep total fat intake between 30% and 35% of calories for children 2 to 3 years of age •

and between 25% and 35% of calories for children 4 to 18 years of age.

Offer fruits, vegetables, fat-free or low-fat dairy, and whole-grain snacks to get the most •

nutrition out of snacks.

Offer child-appropriate portions.

• 54–58

Engage in at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity on most, preferably •

all, days of the week.

Provide food that is safe (eg, by not feeding unpasteurized juices, raw sprouts, raw [un-•

pasteurized] dairy products, raw or partially cooked eggs, and raw or undercooked meat, poultry, fi sh, or shellfi sh), especially to young children.

*Most recommendations are from the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Parenting and the Feeding Relationship

Feeding can be quite challenging, particularly during the toddler and pre-school years. Satter’s division of responsibility—in which parents provide structure in mealtime, a healthy variety of foods, and opportunities for learning and the child ultimately decides how much and whether to eat on a given eating occasion—represents a sound theoretical basis for implement-ing appropriate child-feedimplement-ing practices.59

Structure and routine for eating occasions is particularly important for the young child. Children can be moved to a more adult-like eating pattern with opportunities for consumption being centered on meals and snacks60 (4–6

per day) and limited grazing in between. Adults should decide when food is offered or available and the child should be left to decide how much and whether they choose to eat at a given eating occasion. The physical environ-ment should also be structured to promote healthy eating with distractions from television or other activities avoided. Ideally, eating should occur in a designated area of the home with a developmentally appropriate chair for the child. Family meals, with adults present and eating at least some of the same foods as children, provide occasions to learn and model healthful eat-ing habits as well as opportunities to include the social aspects of eateat-ing.

are required to facilitate children’s acceptance of foods like vegetables and meats that are not sweet.6 However, parental responsibility falls short of

“getting” children to eat or like particular foods. Pressuring children to con-sume foods or rewarding them for consuming specifi c foods is counterpro-ductive in the long run, because it is likely to build resistance and food dis-likes rather than acceptance. Instead, considering mealtime from the child’s perspective—where everything is new and different—and recognizing that fi nicky eating is a normal stage of development that children outgrow—is a more productive outlook. Parents’ concerns can be diminished if the focus becomes the adequacy of children’s growth rather than children’s behavior at individual eating occasions.

Creating positive mealtime environments that are free of distractions (television, loud •

music) with appropriate physical components (chairs, tables, utensils, cups, etc).

Modeling behaviors that they desire their children learn, such as consuming a varied and •

healthy diet.

Regarding mealtime as a time of learning and mastery with respect to eating and social •

skills and with respect to family and community time.

Children decide which of the foods (that are selected by parents) that they will consume. They also decide how much to eat.

Parents can be reminded that:

Foods should be offered repeatedly (10 times) and patiently to establish children’s ac-•

ceptance of the food.

Children need a routine of 3 meals and 2 snacks per day. •

Appropriate demands for mastery (such as using a spoon and drinking from a cup) facilitate •

children’s learning and sense of accomplishment.

Pressure and coercion may have short-term benefi ts but will ultimately make feeding more diffi cult and eating less rewarding and pleasurable.

II

Parents’ feeding styles have been associated with children’s dietary intakeand weight status.62–65 Authoritative feeding, characterized by adults

encour-aging children to eat healthy foods and allowing the child to have limited choices but stopping short of pressuring or forcing, has been associated with increased availability and intake of fruits, vegetables, and dairy and lower intake of “less nutritious” foods.62,66 In contrast, authoritarian feeding,

characterized by attempts to control children’s eating, has been associated with lower intake of fruit, juices, and vegetables. Children who were told to “clean their plates” were less sensitive to physiological cues of satiety.63

Permissive feeding, characterized by little structure in feeding, has been as-sociated with greater intake of fat and sweet foods, more snacks, and fewer healthy food choices.64

Young children respond well when appropriate maturity demands are made. Children wantto learn and wantto eat. They also desire to partici-pate in decisions about their own eating. Allowing them the opportunities for mastery of eating, even when it translates into extra work and mess, ul-timately promotes self-regulation and autonomy building. Experience is the only established predictor of acceptance and liking. Therefore, encouraging learning—using all senses and various modes for learning (eg, food shop-ping and preparation; reading to children about food, eating, and cultures)— can promote more enthusiasm for trying new foods.

Special Topics

Feeding During Illness

A common treatment for acute diarrhea has been a clear liquid diet until symptoms improve. The American Academy of Pediatrics clinical practice guideline on the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children67

recommends that only oral electrolyte solutions be used to rehydrate infants and young children and that a normal diet be continued throughout an episode of gastroenteritis(also see Chapter 28: Oral Therapy for Acute Diar-rhea). Infants and young children can experience a decrease in nutritional status and the illness can be prolonged with a clear liquid diet, especially when it is extended beyond a few days.68 Continuous or early refeeding has

ill-nesses, colds, and other acute childhood illill-nesses, a variety of foods should be offered according to the child’s appetite and tolerance, with extra fl uids provided when fever, diarrhea, or vomiting is present.

Breakfast

Nationally representative data indicate that 8% to 12% of children skip breakfast on any given day, with the numbers growing to 20% to 30% by adolescence.69 Among school-aged children, common barriers to

eat-ing breakfast include lack of time and not beeat-ing hungry in the morneat-ing.70

Children who frequently consume breakfast have superior nutritional profi les compared with those who do not.71 Several studies have also

demonstrated positive effects of breakfast consumption on children’s cog-nitive performance, primarily aspects of memory,72,73 with benefi ts most

pronounced among children at nutritional risk.74,75 Ready-to-eat cereal is

among the top contributors to fi ber, folic acid, vitamin C, iron, and zinc intakes in young children’s diets.39,76 School breakfast programs, which to

a large extent serve children from low-income families,77 are associated

with improvements in children’s nutrient intake and overall diet quality.78

School breakfast participation has also been associated with increases in attendance and academic performance, with benefi ts again most pro-nounced among children at nutritional risk.79–81 The infl uence of breakfast

consumption on body weight is unclear. Some studies have reported a protective association of breakfast consumption on BMI in children,69,82,83

particularly for ready-to-eat breakfast cereal.76,84 Alternatively, breakfast

skippers have generally lower daily energy intakes than do breakfast eat-ers,85,86 suggesting that the behavior may represent a marker of, rather than

a direct contributor to, overweight.71

Obesity (also see Chapter 33: Obesity)

The prevalence of overweight among children has increased drastically over the past 2 decades and is alarmingly high; currently, 25% of children 2 to 18 years of age are overweight.87 Overweight children are at increased

risk of social stigmatization, hyperlipidemia, abnormal glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver disease, and hypertension.88 Environmental

infl uences that promote problematic eating have been given increasing attention in light of the fact that secular increases in overweight have oc-curred too rapidly to be explained by genetic infl uences alone.89,90 Parents

eat-II

fact that the tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood isparticu-larly strong among children who have one or more overweight parents.91

It is recommended that children younger than 3 years with a BMI ≥85th

percentile and with complications of obesity or with a BMI ≥95th percentile

with or without medical complications undergo evaluation and possible treatment.92 When possible, guidance to promote healthful eating patterns in

the overweight child should be directed toward modifying the dietary intake patterns and behaviors of the family as a whole rather than targeting only the overweight child. Referring the family for nutrition and physical activity education and counseling may be useful to help parents discuss behavioral issues involved in child feeding. These discussions should focus on the types of foods that are available in the home, identifying appropriate portion sizes, and incorporating micronutrient-rich, low–energy-density foods into the child’s and family’s diet. Parents should also be made aware that highly restrictive approaches to child feeding are not effective but rather appear to promote the intake of restricted foods18,93 and contribute to low

self-appraisal.94 Furthermore, parents’ should be encouraged to exhibit the eating

behaviors they would like their children to adopt, because children learn to model their parents’ eating and behaviors.21,30

Increased physical activity is a critical component of childhood obesity prevention and treatment, because low-energy diets may compromise the nutrient status of growing children.95 Sedentary behavior has been

associ-ated with overweight among children26,28; health care professionals should

inquire about the amount of time a child spends in front of television, computers, and video monitors and encourage parents to set daily limits for their children. Caregivers have a central responsibility in this area, because they serve as role models for active lifestyles and are children’s gatekeepers to opportunities to be physically active. Health care professionals should convey the importance of encouraging activity of the family as a whole as well as among individuals within the family. Children should be encouraged to participate in discussions about diet and activity modifi cations, both to take into account their preferences and allow them a sense of responsibility for decisions about their behavior.

Beverage Consumption

Fruit juices and soft drinks, including fruit-fl avored and carbonated drinks, are increasingly common beverages consumed by young children at home and in group settings.96 Between 1977 and 2001, soft drink intake among children 2 to

portion size consumed.97 On any given day, 60% of toddlers consumed 100%

fruit juice, with 1 in 10 children consuming more than 14 oz of 100% fruit juice daily.98 Further, sweetened beverages are one of the top 3 contributors (4.7%)

to daily energy intake in this age group, with 40% of toddlers consuming fruit drinks and 11% consuming carbonated beverages on any given day.32 Among

older children, these types of beverages provide roughly 10% of energy in 2- to 19-year-old children’s diets, with soft drinks providing as much as 8% of total daily energy for adolescents.99 Children’s soft drink consumption exceeds that

of 100% fruit juice by 5 years of age and that of milk by 13 years of age.100 Soft

drinks, a main source of added sugar in young children’s diets,101 have been

shown to replace milk in the diet and are associated with lower intakes of key nutrients, particularly calcium (see Appendices L and M).102–107

Failure to thrive has been anecdotally associated with excessive intake of fruit juice,108 and at least 1 study found carbohydrate malabsorption

after consumption of fruit juices in healthy children and in children with chronic nonspecifi c diarrhea.109 In addition, weight gain and adiposity have

been linked to excess energy-containing beverage consumption.110,111 For

all young children, consumption of sweetened beverages should be moni-tored.112 For those with either chronic diarrhea or excessive weight gain,

obtaining a diet history, including the volume of fruit juice and soft drinks consumed, is useful in approaching anticipatory guidance. Intake of fruit juice should be limited to 4 to 6 oz/day for children 1 to 6 years of age.113

For children 7 to 18 years of age, juice intake should be limited to 8 to 12 oz or 2 servings per day. Parents should be encouraged to routinely offer plain, unfl avored water to children, particularly for fl uids consumed outside of meals and snacks.114

Recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends an upper limit of 4 to 6 oz of juice for children 1 to 6 years of age and 8 to 12 oz for children 7 to 18 years of age. Children should be encouraged to consume whole fruits to meet recom-mended levels of fruit intake. Pediatricians should routinely discuss the use of 100% fruit juice and fruit drinks and should educate parents about the differ-ences between the two.

Pediatrics. 2001;107:1210-1213 (Reaffi rmed October 2006)

II

The Role of Anticipatory Guidance in Promoting Healthy EatingBehaviors

The feeding relationship is vital for its role in promoting healthy growth and development but also for its function in engendering healthy behaviors and habits that can prevent the advent of chronic disease. Beyond physiological outcomes associated with poor eating habits and environments, the feed-ing relationship is critical for establishfeed-ing a healthy parent-child relation-ship. Feeding, at its best, provides opportunities for pleasure, learning, and attaining security as well as occasions for self-discovery and for learning self-control.

Food Group

Milk, yogurt, and cheese 1/2 cup

(4 oz)

2 cups 1/2–3/4 cup

(4–6 oz)

2 cups 1/2–1 cup

(4–8 oz)

3 cups Make most choices fat free or low fat.

The following may be substituted for 1/2 cup fl uid milk: 1/2–¾ oz cheese, 1/2 cup

low-fat yogurt, or 21/2 tbsp nonfat dry milk.

Meat, fi sh, poultry, dry beans, eggs, and nuts

1–2 oz 2 oz 1–2 oz 3 oz 2 oz 5 oz Make most choices lean or low fat.

The following may be substituted for 1 oz meat, fi sh, or poultry: 1 egg, 2 tbsp peanut butter, or 4 tbsp cooked dry beans or peas.

Include dark green and orange vegeta-bles, such as carrots, spinach, broccoli, winter squash, or greens. Limit starchy vegetables (potatoes) to 21/2 cups weekly (11/2 cups for 2- to 3-year-olds).

Fruit

PEDIA

TRIC NUTRITION HANDBOOK

Feeding the Child

167

Food Group

Age, y

Comments

2–3 4–8 9–12

Portion

Size Amounts*Daily Portion Size Amounts*Daily Portion Size Amounts*Daily Grains (bread, cereal,

rice, and pasta)

Whole-grain or enriched bread

Cooked cereal

Dry cereal

1/2–1 slice

1/4–1/2 cup

1/2–1 cup

3 oz eq.

1 slice

1/2 cup

1 cup

4 oz eq

1 slice

1/2–1 cup

1 cup

5 oz eq One oz eq equals a 1-oz slice of bread.

The following may be substituted for 1 slice of bread: 1/2 cup spaghetti, maca-roni, noodles, or rice; 5 saltine crackers; 1/2 English muffi n or bagel; 1 tortilla; corn grits; or posole. Make at least 1/2 of grain intake whole grain.

* Daily amounts are from MyPyramid Plans to meet needs for sedentary children of average size at the younger end of each age range. Amounts shown are from 1000-kcal (2- to 3-year-olds), 1200-kcal (4- to 8-year-olds), and 1600-kcal MyPyramid Plans. Active, older, and larger children would need more energy and foods from each group. A specifi c MyPyramid Plan for a child of a specifi ed age, gender, and activity level can be found at http://www.mypyramid.gov/. For children 9 years and older, height and weight can also be specifi ed in selecting a MyPyramid Plan.

References

1. Carruth BR, Skinner JD. Feeding behaviors and other motor development in healthy children (2–24 months). Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:88–96

2. Carruth BR, Ziegler PJ, Gordon A, Hendricks K. Developmental milestones and self-feeding behaviors in infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:S51–S56

3. Burhans KK, Dweck CS. Helplessness in early childhood: the role of contingent worth. Child Dev. 1995;66:1719–1738

4. Desor JA, Maller O, Turner R. Taste acceptance of sugars by human infants. J Comp Physiol

Psychol. 1973;84:496–501

5. Kern DL, McPhee L, Fisher J, Johnson S, Birch LL. The post-ingestive consequences of fat condition preferences for fl avors associated with high dietary fat. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:71–76

6. Sullivan S, Birch L. Pass the sugar; pass the salt: experience dictates preference. Dev

Psychol. 1990;26:546–551

7. Wardle J, Herrera ML, Cooke L, Gibson EL. Modifying children’s food preferences: the effects of exposure and reward on acceptance of an unfamiliar vegetable. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:341–348

8. Wardle J, Cooke LJ, Gibson EL, Sapochnik M, Sheiham A, Lawson M. Increasing children’s acceptance of vegetables; a randomized trial of parent-led exposure. Appetite. 2003;40:155–162

9. Carruth BR, Ziegler P, Gordon A, Barr SI. Prevalence of picky eaters among infants and toddlers and their caregiver’s decisions about offering a food. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:S57–S64

10. Johnson SL, Bellows L, Beckstrom L, Anderson J. Evaluation of a social marketing campaign targeting preschool children. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:44–55

11. Davis CM. Self-selection of diet by newly weaned infants. Am J Dis Child. 1928;36:651–679 12. Davis CM. Results of the self-selection of diets by young children. CMAJ. 1939;41:257–261 13. Birch LL, Billman J, Richards S. Time of day infl uences food acceptability. Appetite.

1984;5:109–116

14. Rolls BJ, Engell D, Birch LL. Serving portion size infl uences 5-year-old but not 3-year-old children’s food intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:232–234

15. Fisher JO, Rolls BJ, Birch LL. Children’s bite size and intake of an entree are greater with large portions than with age-appropriate or self-selected portions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1164–1170

16. Fisher JO. Effects of age on children’s intake of large and self-selected portions. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:403–412

17. Johnson SL, Birch LL. Parents’ and children’s adiposity and eating style. Pediatrics. 1984;94:653–661

18. Birch LL, Fisher JO. Mothers’ child-feeding practices infl uence daughters’ eating and weight.

Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1054–1061

II

20. Hendy HM, Raudenbush B. Effectiveness of teacher modeling to encourage food acceptancein preschool children. Appetite. 2000;34:61–76

21. Cutting TM, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Birch LL. Like mother, like daughter: familial patterns of overweight are mediated by mothers’ dietary disinhibition. Am JClinNutr. 1999;69:608–613

22. Birch LL, Johnson SL, Andresen G, Peters JC, Schulte MC. The variability of young children’s energy intake. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:232–235

23. Birch LL, Deysher M. Conditioned and unconditioned caloric compensation: evidence for self-regulation of food intake by young children. Learn Motiv. 1985;16:341–355

24. Wardle J, Huon G. An experimental investigation of the infl uence of health information on children’s taste preferences. Health Educ Res. 2000;15:39–44

25. Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Bartlett SJ, Cheskin LJ, Pratt M. Relationship of physical activity and television watching with body weight and level of fatness among children: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 1998;279:938–942 26. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Public Education. Children, adolescents, and

television. Pediatrics. 2001;107:423–426

27. Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tucker KL. Relationships between use of television during meals and children’s food consumption patterns. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):e7. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/107/1/e7. Accessed October 31, 2007 28. Crespo CJ, Smit E, Troiano RP, Bartlett SJ, Macera CA, Andersen RE. Television watching,

energy intake, and obesity in US children: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:360–365 29. Wiecha JL, Peterson KE, Ludwig DS, Kim J, Sobol A, Gortmaker SL. When children eat what

they watch: impact of television viewing on dietary intake in youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:436–442

30. Cullen KW, Eagan J, Baranowski T, Owens E, de Moor C. Effect of a la carte and snack bar foods at school on children’s lunchtime intake of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:1482–1486

31. Briefel RR, Reidy K, Karwe V, Jankowski L, Hendricks K. Toddler’s transition to table foods: impact on nutrient intakes and food patterns. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:S38–S44

32. Fox MK, Reidy K, Novak T, Ziegler P. Sources of energy and nutrients in the diets of infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:S28–S42

33. Fox MK, Pac S, Devaney B, Jankowski L. Feeding infants and toddlers study: what foods are infants and toddlers eating? J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:S22–S30

34. Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Subar AF, Cleveland L, Friday J, Kahle LL. Fruit and vegetable intakes of children and adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:81–86

35. Munoz KA, Krebs-Smith SM, Ballard-Barbash R, Cleveland LE. Food intakes of US children and adolescents compared with recommendations. Pediatrics. 1997;100:323–329

37. Ballew C, Kuester S, Serdula M, Bowman B, Dietz W. Nutrient intakes and dietary patterns of young children by dietary fat intakes. J Pediatr. 2000;136:181–187

38. Kant AK. Reported consumption of low-nutrient-density foods by American children and adolescents: nutritional and health correlates, NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med. 2003;157:789–796

39. Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US children, 1989–1991. Pediatrics. 1998;102:913–923

40. Mendoza JA, Drewnowski A, Cheadle A, Christakis DA. Dietary energy density is associated with selected predictors of obesity in U.S. children. J Nutr. 2006;136:1318–1322

41. Jahns L, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. The increasing prevalence of snacking among US children from 1977 to 1996. J Pediatr. 2001;138:493–498

42. Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in U.S. between 1977 and 1996: similar shifts seen across age groups. Obes Res. 2002;5:370–378

43. Bowman SA, Gortmaker SL, Ebbeling CB, Pereira MA, Ludwig DS. Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and diet quality among children in a national household survey. Pediatrics. 2004;113:112–118

44. Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: Applications in Dietary Assessment. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000

45. Alaimo K, McDowell MA, Briefel RR, et al. Dietary intake of vitamins, minerals, and fi ber of persons ages 2 months and over in the United States: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Phase 1, 1988–91. Adv Data. 1994;258:1–28

46. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Life Sciences Research Offi ce.

Third Report on Nutrition Monitoring in the United States: Volume 1. Washington, DC: US

Government Printing Offi ce; 1995

47. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. Statement on cholesterol.

Pediatrics. 1998;101:141–147

48. Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, et al. Dietary guidelines revision 2000: a statement for healthcare professionals from the nutrition committee of the American Heart Association.

J Nutr. 2001;131:132–146

49. Obarzanek E, Hunsberger SA, Van Horn L, et al. Safety of a fat-reduced diet: the Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC). Pediatrics. 1997;100:51–59

50. Butte NF. Fat intake of children in relation to energy requirements. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1246S–1252S

51. US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. Dietary

Guidelines for Americans 2005. 6th ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Offi ce;

2005

52. US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. Finding

Your Way to a Healthier You 2005. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Offi ce; 2005

53. US Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. MyPyramid. Available at: http://www.mypyramid.gov. Accessed October 31, 2007

II

55. Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Patterns and trends in food portion sizes, 1977–1998. JAMA.2003;289:450–453

56. Fox MK, Devaney B, Reidy K, Razafi ndrakoto C, Ziegler P. Relationship between portion size and energy intake among infants and toddlers: evidence of self-regulation. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:77–83

57. McConahy KL, Smicikclas-Wright H, Birch LL, Mitchell DC, Picciano MF. Food portions are positively related to energy intake and body weight in early childhood. J Pediatr. 2002;140:340–347

58. McConahy KL, Smiciklas-Wright H, Mitchell DC, Picciano MF. Portion size of common foods predicts energy intake among preschool-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:975–976 59. Satter E. How to Get Your Kid to Eat…But Not Too Much. Palo Alto, CA: Bull Publishing Co;

1987

60. Skinner JD, Ziegler P, Pac S, DeVaney B. Meal and snack patterns of infants and toddlers.

J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:S65–S70

61. Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Parental feeding attitudes and styles and child body mass index: prospective analysis of a gene-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e429. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ cgi/content/full/114/4/e429. Accessed October 31, 2007

62. Gable S, Lutz S. Household, parent, and child contributions to childhood obesity. Fam Relat. 2000;49:293–300

63. Fisher JO, Birch LL. Restricting access to palatable foods affects children’s behavioral response, food selection, and intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1264–1272

64. De Bourdeaudhuij I. Family food rules and healthy eating in adolescents. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:45–56

65. Rhee KE, Lumeng JC, Appugliese DP, Kaciroti N, Bradley RH. Parenting styles and overweight status in fi rst grade. Pediatrics. 2006;117;2047–2054

66. Patrick H, Nicklas TA, Hughes SO, Morales M. The benefi ts of authoritative feeding style: caregiver feeding styles and children’s food consumption patterns. Appetite. 2005;44:243–249

67. American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis. Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. Pediatrics. 1996;97:424–435

68. Brown KH. Dietary management of acute childhood diarrhea: optimal timing of feeding and appropriate use of milks and mixed diets. J Pediatr. 1991;118:S92–S98

69. Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM, Carson T. Trends in breakfast consumption for children in the United States from 1965–1991. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:748S–756S

70. Reddan J, Wahlstrom K, Reicks M. Children’s perceived benefi ts and barriers in relation to eating breakfast in schools with or without Universal School Breakfast. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34:47–52

71. Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, Adams J, Metzl JD. Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J Am Diet

72. Wesnes KA, Pincock C, Richardson D, Helm G, Hails S. Breakfast reduces declines in attention and memory over the morning in schoolchildren. Appetite. 2003;41:329–331 73. Mahoney CR, Taylor HA, Kanarek RB, Samuel P. Effect of breakfast composition on cognitive

processes in elementary school children. Physiol Behav. 2005;85:635–645

74. Cueto S, Jacoby E, Pollitt E. Breakfast prevents delays of attention and memory functions among nutritionally at-risk boys. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1998;19:219–233

75. Simeon DT, Grantham-McGregor S. Effects of missing breakfast on the cognitive functions of school children of differing nutritional status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;49:646–653

76. Barton BA, Eldridge AL, Thompson D, et al. The relationship of breakfast and cereal consumption to nutrient intake and body mass index: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:1383–1389

77. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. School Breakfast Program

Participation and Meals Served. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture; 2006

78. Bhattacharya J, Currie J, Haider SJ. Evaluating the Impact of School Nutrition Programs:

Final Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service;

2004

79. Powell CA, Walker SP, Chang SM, Grantham-McGregor SM. Nutrition and education: a randomized trial of the effects of breakfast in rural primary school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:873–879

80. Kleinman RE, Hall S, Green H, et al. Diet, breakfast, and academic performance in children.

Ann Nutr Metab. 2002;46(Suppl 1):24–30

81. Murphy JM, Pagano ME, Nachmani J, Sperling P, Kane S, Kleinman RE. The relationship of school breakfast to psychosocial and academic functioning: cross-sectional and longitudinal observations in an inner-city school sample. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:899–907 82. Miech RA, Kumanyika SK, Stettler N, Link BG, Phelan JC, Chang VW. Trends in the

association of poverty with overweight among US adolescents, 1971–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:2385–2393

83. Affenito SG, Thompson DR, Barton BA, et al. Breakfast consumption by African-American and white adolescent girls correlates positively with calcium and fi ber intake and negatively with body mass index. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:938–945

84. Albertson AM, Anderson GH, Crockett SJ, Goebel MT. Ready-to-eat cereal consumption: its relationship with BMI and nutrient intake of children aged 4 to 12 years. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:1613–1619

85. Berkey CS, Rockett HR, Gillman MW, Field AE, Colditz GA. Longitudinal study of skipping breakfast and weight change in adolescents. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1258–1266

86. Cho S, Dietrich M, Brown CJ, Clark CA, Block G. The effect of breakfast type on total daily energy intake and body mass index: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22:296–302

II

89. Hill JO, Peters JC. Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science.1998;280:1371–1374

90. Poston WS, Foreyt JP. Obesity is an environmental issue. Atherosclerosis. 1999;146:201–209 91. Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young

adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:869–873 92. Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Obesity evaluation and treatment: expert committee

recommendations. The Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3):e29. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/102/3/ e29. Accessed October 31, 2007

93. Fisher JO, Birch LL. Restricting access to foods and children’s eating. Appetite. 1999;32:405–419

94. Davison KK, Birch LL. Weight status, parent reaction, and self-concept in fi ve-year-old girls.

Pediatrics. 2001;107:46–53

95. Goran MI, Reynolds KD, Lindquist CH. Role of physical activity in the prevention of obesity in children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:S18–S33

96. Briefel RR, Johnson CL. Secular trends in dietary intake in the United States. Ann Rev Nutr. 2004;24:401–31

97. Nielsen SJ, Popkin B. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:205–210

98. Skinner JD, Ziegler P, Ponza M. Transitions in infants’ and toddlers’ beverage patterns. J Am

Diet Assoc. 2004;104:S45–S50

99. Troiano RP, Briefel RR, Carroll MD, Bialostosky K. Energy and fat intakes of children and adolescents in the United States: data from the national health and nutrition examination surveys. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1343S–1353S

100. Rampersaud GC, Bailey LB, Kauwell GP. National survey beverage consumption data for children and adolescents indicate the need to encourage a shift toward more nutritive beverages. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:97–100

101. Kranz S, Smiciklas-Wright H, Siega-Riz AM, Mitchell D. Adverse effect of high added sugar consumption on dietary intake in American preschoolers. J Pediatr. 2005;146:105–111 102. Harnack L, Stang J, Story M. Soft drink consumption among US children and adolescents:

nutritional consequences. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:436–441

103. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. Calcium requirements of infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1152–1157

104. Fisher JO, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Maternal milk consumption predicts the trade-off between milk and soft drinks in young girls’ diets. J Nutr.

2001;131:246–250

105. Striegel-Moore RH, Thompson D, Affenito SG, et al. Correlates of beverage intake in adolescent girls: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study.

J Pediatr. 2006;148:183–187

106. Frary CD, Johnson RK, Wang MQ. Children and adolescents’ choices of foods and beverages high in added sugars are associated with intakes of key nutrients and food groups. J Adolesc

107. Marshall TA, Eichenberger Gilmore JM, Broffi tt B, Stumbo PJ, Levy SM. Diet quality in young children is infl uenced by beverage consumption. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24:65–75

108. Smith MM, Lifshitz F. Excess fruit juice consumption as a contributing factor in nonorganic failure to thrive. Pediatrics. 1994;93:438–443

109. Lifshitz F, Ament ME, Kleinman RE, et al. Role of juice carbohydrate malabsorption in chronic non-specifi c diarrhea in children. J Pediatr. 1992;120:825–829

110. Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357:505–508

111. Welsh JA, Cogswell ME, Rogers S, Rockett H, Mei Z, Grummer-Strawn LM. Overweight among low-income preschool children associated with the consumption of sweet drinks: Missouri, 1999–2002. Pediatrics. 2005;115:223–229

112. Dietz WH. Sugar-sweetened beverages, milk intake, and obesity in children and adolescents.

J Pediatr. 2006;148:152–154

113. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. The use and misuse of fruit juice in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1210–1213