3

Pre-Service English Teachers’ Collaborative Learning Experience as Reflected in Genre-Based Writing

Didik Rinan Sumekto

Widya Dharma University, Klaten, Indonesia [email protected]

Abstract

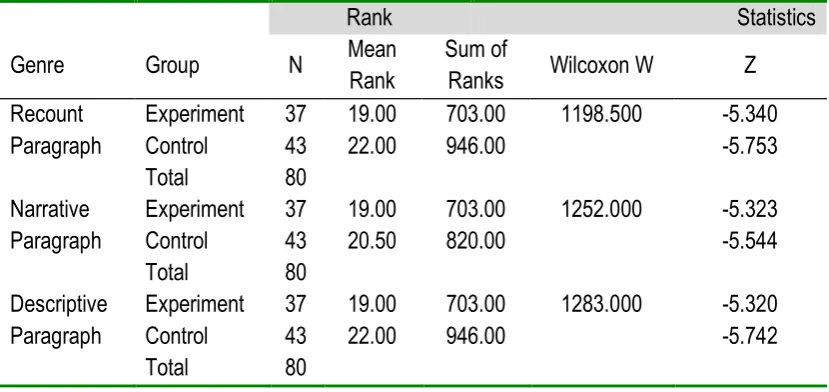

This study aims at investigating pre-service English teachers’ collaborative learning as reflected in genre-based writing classes. 37 PSETs involved as the experimental group, 43 PSETs participated as the control group. Data collection used observation and questionnaire through the quasi-experimental method. Data were analyzed through the multivariate for GLM model, Wilcoxon Signed-Rank, and qualitative descriptive. The findings showed PSETs’ achievement significantly increased (p<.01) after PSETs’ collaborative learning was engaged. The paired samples test were M=2.744; SD=1.347 for recount, M=2.767; SD=1.771 for narrative, and M=3.488; SD=1.594 for descriptive paragraphs. The experimental group tests were 5.340; p<.01 for recount, Z=-5.323; p<.01 for narrative, and Z=-5.320; p<.01 for descriptive paragraphs. Pre- and post-tests fulfilled genres’ achievement criteria. Mean increased among those paragraphs (recount=70.51 to 73.26; narrative=71.58 to 74.35, and descriptive=71.07 to 74.56). Another finding indicated 45 respondents positively responded to the collaborative learning practice, whereas 11 respondents had problems with the practice.

Keywords: collaborative learning, genre-based writing, PSETs

Introduction

4

the L2 students’ needs requires a change in both lecturer’s classroom perspectives and pedagogical practices. This is to demonstrate promising opportunities for changing students’ attitudes, especially when they involve topics-based experience (Steele et al, 2013).

Accordingly, genre knowledge facilitates consciousness-raising, enhances academic literacy, develops students’ self-efficacy, and improves writing performance (Lee, 2012), since each genre has its own features and structures to express the intended meaning (Sullivan, Zhang, & Zheng, 2012). Genre is a term for grouping texts together, representing how writers typically use language to respond to recurring situations (Hyland, 2008) within generating and organizing ideas by using an appropriate choice of vocabulary, sentence, and paragraph organization, as well as turning such ideas into a readable text (Richards & Renandya, 2002; Widodo, 2006). According to Tai, Lin and Yang (2015), writing assessment consists of five equally weighted criteria, such as content-the logical development of ideas; organization-introduction, body, and conclusion; grammar; mechanics-punctuation, spelling, and vocabulary use; and style-writing style and quality of expression. This means responding to the specific instructional contexts, L1 or L2 and experience, writing purposes and providing extensive encouragement in the form of meaningful contexts, peer involvement, prior texts, useful feedback and guidance in the writing process (Hyland, 2003) to coordinate and integrate their linguistic usage (Kern, 2000).

5

peers, present and defend ideas, exchange diverse beliefs, ask other conceptual frameworks, and be actively engaged in the classroom-based learning process (Brown, 2008), as well as allows them to share ideas and learning experiences, and further promote the learning performance of either groups or individuals (Kuo, Chu, & Huang, 2015).

Some studies focused this collaborative learning on the majority of students’ satisfaction concerning with the shared and mutual learning. The score showed 84% students had scored 5 and 14% students had scored 4 out of maximum 5 Likert scale. Meanwhile, the creative thinking stimulation had been considered as an important contribution method which was chosen by 76% students who scored 5 and 23% students who scored 4 out of the maximum 5 Likert scale points (Mureșan, 2015). Next, Liu and Lan (2016) proved that working collaboratively in EFL classroom increased the motivational beliefs and self-efficacy. The motivational beliefs had a higher level than the individuals, as shown by the mean scores of 3.69 and 3.36. It differed significantly between the groups; collaborators, SD=5.36, individuals, SD=4.54, t(53)=2.68, p<.01 with a medium effect size, r=.35). Similar to the motivational beliefs, the self-efficacy had a higher level than the individuals. The level of self-efficacy was significantly different between the groups; collaborators, M=3.88, SD=2.67, whereas individuals, M=3.45, SD=2.73, t(53)=2.90, p<.005.

Another reason for conducting this study related to the accomplishment of tasks, team members’ morphological knowledge and text accurateness use. The collaboration process and working together among the group members played a significant role in the overall performance, besides improving the grammatical accuracy through the multiple revision processes (Ansari, 2012). Further, Almajed et al (2016) supported seven key facilitating factors that positively affected students’ collaborative learning; they were coherence toward learning, group organization, learning preparation, accountability, relaxed environment, relevant topics, and tutor support. The last but not least, students’ positive beliefs and values regarded the collaborative work and peer feedback in L2 writing, students’ motives and goals provided the assistance and mutual learning, use of various mediating artifacts, and power relationships (Yu, 2015).

6

How the collaborative learning effectiveness can be measured through the genre-based writing’s peer feedback?

Method

This study was conducted at English Education Department, Sarjanawiyata Tamansiswa University, Yogyakarta throughout the first semester of 2014-2015 academic year. 80 pre-service English teachers (PSETs) participated in genre-based writing. 37 PSETs involved as the experimental groups, whilst 43 PSETs were engaged to be the control groups through the quasi-experimental approach.

Class was a 18-week course (120 minutes per week) designed to conduct PSETs’ collaborative learning in recount, narrative, and descriptive paragraphs. Genres were listed in lecturer’s lesson plans. The PSETs’ collaborative learning procedure started with the classroom-based instruction and assignment that involved the selected genres thoroughly in the course weeks. They were provided into 4 to 5 members in a group during the collaboration. A selected genre was introduced by the lecturer. Time allotment was practically given more or less 40 minutes to the group members. Members were allowed to discuss with others outside their home-base group or rotated to other peers. The peer feedback was based on PSETs’ collaborative works, allocated within 20 minutes revision. The remainder times were used by the lecturer to correct and discuss the genre paragraphs.

Data collection used the participatory observation and instruction evaluation sheet that was applied to analyze genre-based writing classes and need analysis questionnaire to obtain PSETs’ genre-based writing achievement. Data were analyzed through the general linear model (GLM) and Wilcoxon Signed-Rank to gain pre- and post-test results (Creswell, 2005), which presumed the accuracy and reliability, and multivariate analysis of variance (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007). The Likert scale was undertaken to indicate PSETs’ collaborative works, whereas the qualitative descriptive method was applied to interpret PSETs’ collaborative work reflections.

Results and Discussion

7

format, instruments, meeting schedule and evaluation. Tai, Lin, and Yang (2015) emphasized that the peer feedback led to enhance the effectiveness of the course delivery and to apply stronger collaborations into PSETs’ learning. Genre-based writing classes proved to be more meaningful and more effective, since the PSETs were well-facilitated by the certain feedback devices that accommodated the objectives and learning motivation. Practically, they needed extra times to make adjustment in the collaborative works. Individual PSETs had a better opportunity to learn with the selected genres based on their knowledge and experience, and work collaboratively without neglecting personal writing paragraphs.

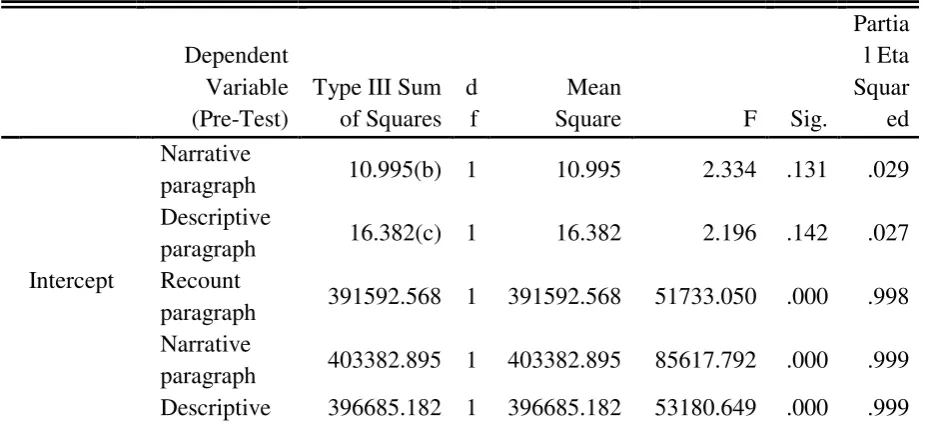

The genre-based writing achievements showed very significant (p<.01) after the PSETs attended a series of collaborative genre-based writing classes. The paired samples test on recount (M=2.744; SD=1.347), narrative (M=2.767; SD=1.771), and descriptive paragraphs (M=3.488; SD=1.594). The experimental pre- and post-tests results indicated an improvement. The mean increased from 70.51 to 73.26 for recount; 71.58 to 74.35 for narrative; and 71.07 to 74.56 for descriptive paragraphs. Table 1 showed the collaborative genre-based writing aimed at indicating the transfer of learning achievement, where recount (F=1.290; p=.000; Adj R²=.016), narrative (F=2.334; p=.000; Adj R²=.029), and descriptive paragraphs (F=2.196; p=.000; Adj R²=.027) which reflected PSETs’ creativity, mutual understanding, social interaction and relationships, communication engagement, procedure and problem-solving within the entirely activities.

Table 1. Variance Tests Analysis of Inter Genre-Based Writing (n=80)

Dependent

paragraph 391592.568 1 391592.568 51733.050 .000 .998 Narrative

8

9

Table 2. GLM Repeated Measures Analysis of Genre-Based Writing

Effect Value F

Hypoth

esis df Error df Sig.

Intercept Pillai's Trace .999 38717.078(a) 3.000 76.000 .000

Wilks' Lambda .001 38717.078(a) 3.000 76.000 .000

Hotelling's Trace 1528.306 38717.078(a) 3.000 76.000 .000

Roy's Largest Root 1528.306 38717.078(a) 3.000 76.000 .000

Group Pillai's Trace .045 1.187(a) 3.000 76.000 .320

Wilks' Lambda .955 1.187(a) 3.000 76.000 .320

Hotelling's Trace .047 1.187(a) 3.000 76.000 .320

Roy's Largest Root .047 1.187(a) 3.000 76.000 .320

Intercept Pillai's Trace 1.000 57343.633(a) 3.000 76.000 .000

Wilks' Lambda .000 57343.633(a) 3.000 76.000 .000

Hotelling's Trace 2263.564 57343.633(a) 3.000 76.000 .000

Roy's Largest Root 2263.564 57343.633(a) 3.000 76.000 .000

Group Pillai's Trace .194 6.114(a) 3.000 76.000 .001

Wilks' Lambda .806 6.114(a) 3.000 76.000 .001

Hotelling's Trace .241 6.114(a) 3.000 76.000 .001

Roy's Largest Root .241 6.114(a) 3.000 76.000 .001

a Exact statistic; b Design: Intercept+Group

10

Table 3. PSETs’ Genre-Based Writing Classes Effectiveness

Genre Group

11

comfortable and no anxiety”, “The topic is easy to understand and students enjoy the materials”, “I think working with peer is enjoyable”, “I like this learning process, it is interesting and makes me work hard”, “It gives experience in working with group”, “Collaborative learning helps students to write assignments together”, “The students will know more about understanding texts and correcting other writing works through collaborative learning”, “I can know and learn more about the mistakes I have made during the activity when peer feedback is being conducted”, “Collaborative learning is appropriate to practice”, “When I corrected my friend’s work, it helped me to improve my sensitivity in errors revision”, “I enjoy joining in writing class because I can explore my own ideas”, “I can ask my friends for writing III as long as I have difficulties”, “When I follow the learning process (writing III), I can know how to make essay and the topic is not quite difficult to me”, “I think the lecturer gives us good materials in writing III. I am happy and interested in joining this class”, “The students need to work with peer or group because it is able to assist them in learning and solving the problem”, “Actually working in a group is one of ways to understand or identify the problem. By doing so, we can share our ideas to solve the problems”, “This class is so interesting and I have good chances to make paragraphs”, “The learning process is so relaxed in every meeting”, “I am happy to follow this learning process, because I may consult easily with the lecturer”, “Sometimes I enjoy working with peers, because I can find out my weaknesses through my friend’s feedback”, “So far, the activity was good enough to help our skills”, “The learning activity enables the students to discuss some assignments in groups”, “The learning activity enables the students to discuss some assignments in groups”, “Working with peers will be beneficial to revise some mistakes and to improve the accuracy of peers’ works”, “I enjoy working with peers very much and I hope it will be better again”, “I am interested in joining the collaborative learning, particularly in writing”, “I enjoy working with peers very much and I hope it will be better again”, “I am interested in joining the collaborative learning, particularly in writing”, “It is a wonderful learning process in this semester and I think I still need more challenges”, and “I prefer to work collaboratively with peers since it makes me improve and be more confident in doing assignments”.

12

delivering the materials, because I think it makes the students confused. So, I think the lecturer should ask the students before teaching”, “There are some friends who do not really understand about the teaching and learning materials, although the lecturer has explained it clearly”, “I think the lecturer should teach and speak clearly and slow, so that the students can understand it well”, “The assignment is hard to understand, actually when my peer corrects the report text”, “Some students are not willing to work and participate in groups during the activity”, “I get difficulties when learning some genres. I hope the lecturer understands about the students’ writing ability”, “I think it is not easy to understand as long as I join in writing subject. There are some writing genres that I should understand”, “When I shall work with other peers, it depends on the topic given because if we are not familiar with the topic, working together in a group will waste of time to understand the topic”, “Sometimes working with peers is also difficult because we have different minds with our friends”, and “I prefer to work individually because I can totally concentrate with the task”. However, Figure 1 summarized 45 versus 11 participants’ perception relating to the collaborative learning.

Figure 1. PSETs’ positive and negative comments

These findings showed the empirical evidence of the collaborative learning that reflected PSETs’ genre-based writing achievement. The collaborative learning could be regularly handled as a means of PSETs’ teaching and learning improvement. The considerably reason supported this constructivist learning instead of the conventional learning. The collaborative learning would be well-structured with the elaborated learning content organization as documented in the lesson plans. It could primarily compromise with the peer feedback improvement purposes by considering PSETs’ readiness, backgrounds, benefits, and weaknesses.

0 10 20 30 40 50

13 Conclusion

The collaborative learning was considered as the habit of learning in group appreciation and appropriateness. This prioritized group objectives and gained sense of both individuals and groups responsibility. The PSETs were given opportunities to use their generic competence and interpersonal skills in endeavor it concerned with and how to solve the problems, well-organized and timed-manageable lectures. The design also supported the factual experiences in realizing the authentic, fair, holistic, and meaningful learning strategy. For the practical use, this learning approach was substantially concerned with the genre-based writing classes’ constructiveness context, where the elaboration stage undertook from simple-to-complex procedure. It meant that the collaborative learning design significantly contributed to the peer feedback practice, which might increase both the problem-solving and stimulate the collaborative learning engagement. The effectiveness of peer feedback was gained within the genre-based writing classes. Hence, this feedback had feasibility, adaptability and significance functions, determined as the alternative feedback to meet the learning objectives.

The collaborative genre-based writing became more intensive. This climate corresponded to the mutual peer feedback and information sharing during the sessions. The PSETs were attractive and willing to do with the best works in groups when revising the peer works. As a part of learning process, the peer feedback worked effectively in groups. The learning circumstance was not so rigid, but it was reasonably fair enough. All participants attempted at constructing and solving the problems, as well as increased the learning quality. Accordingly, being observed from PSETs’ collaborative work, both experimental and control groups showed a positive learning behavior through their genre-based writing achievements and constructive social interaction. Alternatively, non-academic achievements undertook the mutual commitment of problem-solving efforts. These efforts, indeed, accomplished a series of availability on interaction quality, time sufficiency, collaboration commitment within others, tasks and learning appointments, and fairness in a group-work.

Bio Data

14

Regency, Indonesia; 2015 to present. His e-mail address: [email protected].

References

Almajed, A., Skinner, V., Peterson, R., & Winning, T. (2016). Collaborative learning: Students’ perspectives on how learning happens. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 10(2), 1-17. doi: 10.7771/1541-5015.1601

Ansari, D. N. (2012). The effect of collaboration on Iranian EFL learners’ writing accuracy. International Education Studies, 5(2), 125-131.

Brown, A., & Danaher, P. (2008). Towards collaborative professional learning in the first year early childhood teacher education practicum: Issues in negotiating the multiple interests of stakeholder feedback. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 36(2), 147-161. doi: 10.1080/13598660801958879

Brown, F. A. (2008). Collaborative learning in the EAP classroom: Students’ perceptions. English for Specific Purposes, 7(1), 1-18. Retrieved

October 15th, 2012, from

http://www.esp-world.info/Articles_17/PDF/Collaborativelearning.pdf

Cohen, L, Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education (6th ed.). Oxon: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. New York: Pearson Education, Inc.

Eftekharian, E., & Tayebipour, F. (2015). On the effects of pair work on EFL learners' writing. Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods, 5(3), 100-112.

15

Hyland, K. (2003). Genre-based pedagogies: A social response to process. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12, 17-29.

Kern, R. (2000). Literacy and language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kuo, Y.-C., Chu, H.-C., & Huang, C.-H. (2015). A learning style-based grouping collaborative learning approach to improve EFL students’ performance in English courses. Educational Technology & Society, 18(2), 284-298.

Lambatos, L. R. (2007). Redefining teachers’ role: A collaborative paradigm for ELL teachers and title I reading specialists to serve a bilingual learning community (Dissertation’s Thesis). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3272157)

Lee, I. (2012). Genre-based teaching and assessment in secondary English classrooms. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 11(4), 120-136.

Liu, S. H. J., & Lan, Y. J. (2016). Social constructivist approach to web-based EFL learning: Collaboration, motivation, and perception on the use of Google docs. Educational Technology & Society, 19(1), 171-186.

Majumdar, S. (2011). Teacher education in TVET: Developing a new paradigm. International Journal of Training Research, 9(1-2), 49-59.

Malm, B. (2009). Towards a new professionalism: Enhancing personal and professional development in teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 35(1), 77-91.

Muijs, D., Ainscow, M., Chapman, C., & West, M. (2011). Collaboration and networking in education. London: Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

Mureșan, M. (2015). Collaborative learning and cybergogy paradigms for the development of transversal competences in higher education. Euromentor Journal, 6(2), 21-29.

16

Nayan, S., Shafie, L. A., Mansor, M., Maesin, A., & Osman, N. (2010). The practice of collaborative learning among lecturers in Malaysia. Management Science and Engineering, 4(1), 62-70.

Osterholt, D. A., & Barratt, K. (2010). Ideas for practice: A collaborative look to the classroom. Journal of Developmental Education, 34(2), 26-35.

Richards, J. C., & Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. In R. A. Reppen, A Genre-Based Approach to Content Writing Instruction (pp. 321-327). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schamber, J. F., & Mahoney, S. L. (2006). Assessing and improving the quality of group critical thinking exhibited in the final projects of collaborative learning groups. The Journal of General Education, 55(2), 103-137.

Schulz, M. M. (2009). Effective writing assessment and instruction for young English language learners. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37, 57-62.

Sela, O. (2013). Old concepts, new tools: An action research project on computer-supported collaborative learning in teacher education, MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(3), 418-430.

Steele, A., Brew, C., Rees, C., & Ibrahim-Khan, S. (2013). Our practice, their readiness: Teacher educators collaborate to explore and improve preservice teacher readiness for Science and Math instruction, Journal of Scientific Teacher Education, 24, 111-131. doi: 10.1007/s10972-012-9311-2

Sullivan, P., Zhang, Y., & Zheng, F. (2012). College writing in China and America: A modest and humble conversation, with writing samples. The Journal of the Conference on College Composition and Communication, 64(2), 306-331.

17

Wake, D. G., & Modla, V. B. (2012). Using wikis with teacher candidates: Promoting collaborative practice and contextual analysis. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 44(3), 243-265.

Widodo, H. P. (2006). Designing a genre-based lesson plan for an academic writing course. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 5(3), 173-199.

Woo, M., Chu, S., Ho, A., & Li, X. (2011). Using a wiki to scaffold primary-school students' collaborative writing. Educational Technology & Society, 14(1), 43-54. Retrieved February 12th, 2017, from http://www.ifets.info/journals/14_1/5.pdf