Volume 7, Number 11, November 2010 (Serial Number 61)

Jour nal of US-China

Public Administration

David Publishing Company located at 1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, Illinois 60048, USA.

Aims and Scope:

Journal of US-China Public Administration, a professional academic journal, commits itself to promoting the academic communication about analysis of developments in the organizational, administrative and policy sciences, covers all sorts of researches on social security, public management, land resource management, educational economy and management, social medicine and health service management, national political and economical affairs, social work, management theory and practice etc. and tries to provide a platform for experts and scholars worldwide to exchange their latest researches and findings.

Editorial Board Members:

Juraj Nemec (professor, Matej Bel University, Slovakia) Sangeeta Sharma (professor, University of Rajasthan, India)

Adrian Gorun (professor, “Constantin Brâncuşi” University of Târgu-Jiu, Romania) Raghuvar Dutt Pathak (professor, University of the South Pacific, Fiji)

Mustafa Kemal Öktem (associate professor, Hacettepe University, Turkey)

Wong Cham Li (associate professor, Macau University of Science and Technology, China) Shakespeare M. Binza (associate professor, University of South Africa, South Africa) Maja Klun (assistant professor, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia)

Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web Submission, or E-mail to [email protected]. Submission guidelines and Web Submission system are available at http://www.davidpublishing.com

Editorial Office:

1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160 Libertyville, Illinois 60048 Tel: 1-847-281-9826

Fax: 1-847-281-9855

E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]

Copyright©2010 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including various websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation, however, all the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author.

Abstracted / Indexed in:

Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA Chinese Database of CEPS, Airiti Inc. & OCLC

Chinese Scientific Journals Database, VIP Corporation, Chongqing, P.R.China Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory

ProQuest/CSA Social Science Collection, Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS), USA Summon Serials Solutions

Subscription Information:

Print $420 Online $320 Print and Online $600 (per year)

For past issues, please contact: [email protected], [email protected]

David Publishing Company

1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, Illinois 60048 Tel: 1-847-281-9826. Fax: 1-847-281-9855

Jour na l of U S-China

Public Adm inist rat ion

Volume 7, Number 11, November 2010 (Serial Number 61)

Contents

Theoretical Investigation

Education as an equalizer and challenges to the American Republic 1

Alexander Dawoody

Anonymous electronic identity in cross-border and cross-sector environment 16

Libor Neumann

The world after financial crisis 28

Esko Kalevi Juntunen

Practice and Exploration

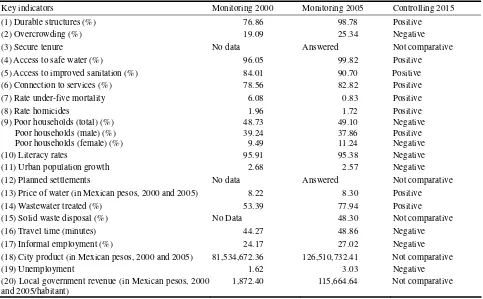

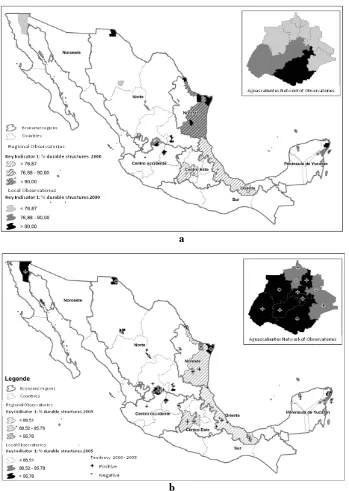

Indicators of the Habitat Agenda in Mexico: Local urban observatory programme 39

Oscar Frausto Martínez, Max Welch Guera

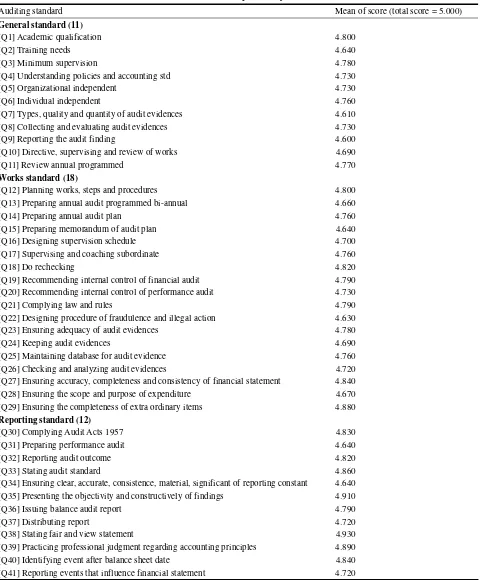

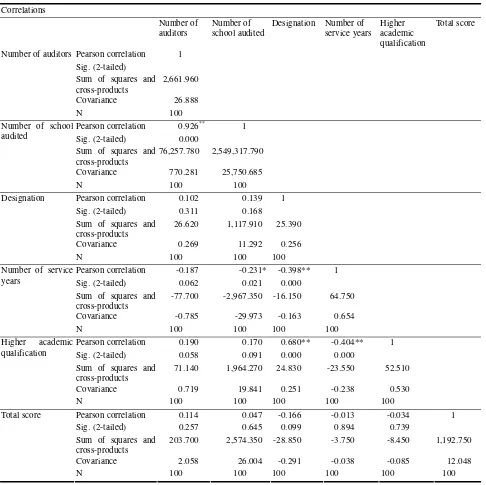

Developing the school financial audit model 46

Khalid Ismail, Kamisan Gadar, Mohd Shoki Md Arif

Internet as a source of information for tourists—The case of Croatia 56

Nada Zgrabljić Rotar, Mili Razović, Josip Vidaković

A model for adoption of mobile banking services using classification and regression trees 66

Samaneh Sorournejad, Amirhassan Monadjemi, Zahra Zojaji

Special Research

From local to global: Can local journalism be a new approach to environmental awareness? 74

Şule Yüksel Öztürk, Şerife Özgün Çıtak

Educational figures as models for empathetic communication at school: An exploratory

examination of an integrative assessment model 85

Yuval Wolf, Ronit Peled Laskov

Foreign ownership of land in Phuket, Thailand 92

Education as an equalizer and challenges to the American Republic

Alexander Dawoody

(Faculty of Public Policy and Administration, Marywood University, Scranton PA 18509, USA)

Abstract: This paper compares the educational system in the United States with those in two other countries. One is Sweden, a developed country that enjoys peace and social tranquility; the other is Iraq, a developing country that is torn by wars and tyrannical political systems. Based on such comparison and while acknowledging

historic differences between the three countries, this paper will identify “cost of education” as a major causal agent in producing two social groups. The first group is a small, elitist cluster emerging as the leading force in all

aspects of society and governance; the second group is a larger under-educated cluster, suffering from insufficient resources and forced into marginalization as voiceless, non-productive, non-competitive and expendable segment in society while plagued by poverty, or under unemployment, crime and economic hardship. In recognizing the

limitation of access to education by the second group as the primary causal element in such disparity, this paper recommends “free access to quality education” as a fundamental right for all Americans and as an equalizer in

correcting the American regime values in order to remain competitive in challenging. Key words: access; cost; performance; decentralization; autonomy

1. Introduction

Education is a fundamental right of every human being. An educated citizen is the primary ingredient for the assurance and defense of freedom. No citizen should be denied access to education because of cost, location,

disability, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, culture or nationality. One of the important tasks of any government is to assure such access and continue to provide resources to improve the quality, progress and development of educational performance. Without education, citizens will be deprived of opportunities to improve their lots in life,

secure their individual freedoms and rights, and hold government accountable to the public.

This paper compares the educational system in the United States with that of two other countries. One is

Sweden, a developed country that enjoys peace and social tranquility; the other is Iraq, a developing country that is torn by wars and tyrannical political systems. Based on such comparison and while acknowledging the historic differences between the three countries, this paper suggests that the concepts of cost, funding and performance are

intertwined in educational sphere and are impacting the issue of access to education. By creating an environment that nourishes disparities in funding while refraining from shifting cost of education to society from the individual

citizen, a condition is created whereby a two-tiered social system is emerging. One tier, although small in size but possessing all elements of power in the country; the other tier, although larger in size yet lacking access to power and the decision-making process in governance. The larger group is increasingly marginalized as voiceless,

non-productive, non-competitive and expendable segment that is plagued by poverty, under/unemployment, crime and economic hardship.

The research design of this paper is qualitative in its nature. It uses a content analysis of selected documents, archival records, studies and articles to compose themes that will answer the following questions:

(1) What is the emerging challenge facing the education system in the United States? (2) How do cost and educational funding create disparities in the American society?

(3) How does the shifting of educational cost directly from the citizen to the society help in creating an

egalitarian community?

(4) What can America learn from countries that shift cost of education from directly to the citizen toward

indirectly to the society?

(5) How can the United States remain competitive in today’s globalization? (6) Is education a fundamental human right issue?

The assumption in this paper is that access to education is vital in maintaining an egalitarian society that allows all its members to contribute to the overall progress of the collective while advancing individual freedom

and prosperity. In order for such an access to remain equitable, it must be designed based on a formula that would assign cost to the public and shift the direct cost of education from the citizen/student to society as a whole. In applying cost-benefit analysis to issues of cost and performance and by looking at a comparative analysis of the

educational systems in the United States, Sweden and Iraq, this paper suggests that the allocation of educational cost indirectly to society will yield far greater goods and benefits to the country than if cost applied directly to the

citizen/student. Such benefits can create a knowledge-based society that will transform the United States from a two-tiered societal nation into more of an egalitarian country based on equality and social justice. An egalitarian and knowledge-based society is able to remain competitive at global level, move toward peaceful and collaborative

engagements with other nations in the world, strengthen its national security by abandoning archaic and costly militaristic tendencies, and diffusing the negative consequences generated by engagements in wars and militarism.

Hence, this paper identifies cost and its direct applicability to the citizen/student as the pivotal challenge to the education system in the United States, especially when such cost is intertwined with issues of funding and performance. To meet the rising cost of education and the continuous decrease in external funding, for example,

most learning institutions in the United States are forced to raise the rate of students’ tuitions and fees in order to meet their operational needs (Yudof, 2002, p. 1). This rise in cost negatively impacts those who have to bear its

direct burden: the citizens/students and their families (Chubb & Moe, 1990, pp. 16-19). The result will impact the issue of access to education and force many students to drop-out and join the massive unskilled labor force (Stone, Pirone & Paxton, 2008, p. 1).

According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, access to private schools and higher learning institutionsis virtually impossible for many Americans despite government-supported loans, grants or scholarships (Strauss &

Howe, 2005, p. 1). According to the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, access to public education is also becoming increasingly expensive (Twigg, 2005, p. 1). Many school districts and public institute of higher learning have inadequate funds necessary to improve teachers’ training or provide sufficient supply for

teaching (Allen, 1997, p. 1). This is in addition to problems of deteriorating school buildings infrastructure in poorer districts (Herbert, 2008, p. 1; Hopkins, 1998, p. 1), overcrowded classrooms in large urban areas (CBS

News, 2009, p. 1; Eberts, Schwartz & Stone, 1990, p. 138) and outdated curriculum on a whole (Duncan, 2009, p. 1; Headden, 1997, p. 1). Coupled with these problems is the issue of ineffective bureaucratic top-down mandates, such as “No Child Left Behind” (NCLB) policy. According to Federal Education Budget Project,such policy is

Budget Project, n.d., p. 1) by forcing them to place importance on teaching for testing (Neill, 2003, p. 1) while punishing the poorer districts for lack of performance caused by low funding (University of Washington-Bothell,

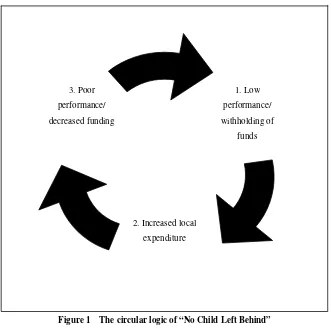

2005, p. 1). Figure 1 demonstrates the circular logic of NCLB:

Figure 1 The circular logic of “No Child Left Behind”

Source: Dawoody, 2008, p. 4.

The diagram illustrates that the logic of NCLB leads from one failed situation to another. When a school

district is performing low, for example, due to lack of funding, teaching and technical capacities or curriculum, NCLB penalizes this district for such a failure and federal funding will be withheld. This punishment will continue until performance is improved. To address such a challenge school districts will have to rely on local

funding in order to improve their performance. When local funding, however, is not capable of meeting the demands of improving public education or NCLB requirements, performance will further deteriorate, a condition

that will lead to more cuts in federal funding up to shutting down the targeted low performing school (Dawoody, 2008, p. 4).

On the flip-side of the coin, families who are able to save money for their children’s education or secure

financial means to fund their children’s education by enrolling them in private institutions (Heller, 2009, p. 1; Kafer, 2004, p. 1) are able to witness better results in their children’s educational performance (Geller, Sjoquist &

Walker, 2001, p. 1). The outcome of this phenomenon is a cadre of professionals capable of securing good quality of life (Lemann, 2001, p. 1; Manning, 1999, p. 1) who, nevertheless, remain minority in comparison with the larger group that lacks the means to benefit from the privileges of good education (Fauth, Brady-Smith &

Brooks-Gunn, n.d., p. 1; Kozol, 1992, pp. 27-34).

1. Low performance/ withholding of

funds

2. Increased local expenditure 3. Poor

In an increasingly competitive globalized economy, the under-educated group finds itself threatened with menial, low-paying jobs or unemployment. The educated elitist group, on the other hand, finds itself benefiting

from utilizing its education in pursue of happiness in life. The emerging society, as a consequence, is a non-egalitarian society that rests its decision-making process at the hands of its elitist group (Fogel, 2000, pp. 312-330). Public policy hence becomes an arena for social construction to benefit the interest of the elitist group

(Schneider & Ingram, 1993, pp. 342-346).

Not all aspects of public education in the United States, however, lack excellence in educational performance.

The Center on Education Policy, for example, suggests that there are some public education schools and institutions of higher learning that match private learning institutions in educational quality and output (Wenglinsky, 2007, p. 1). These, nevertheless, are exceptional cases that witnessed increase in performance

associated with increase in funding generated by higher fees applied to students (Yudof, 2002, p. 1).

By re-emphasizing one of the paper’s core question regarding what to do in order to transform the United

States from a country dominated by the elites (Henry, 1995, p. 5) to a true egalitarian nation of the people, by the people, let us look at the educational performances of two other systems in the world and compare them with that of ours. The comparison ought to give us a better perspective on how to remedy the problem of cost, secure our

future, and remain competitive at global level. One of the two educational systems is located in Sweden, a developed democratic country in Europe that enjoys peace and social tranquility. The other is in Iraq, a developing

country that is torn by wars and tyrannical governments.

Although both of these two countries have great social, political and historic differences with the United States and are much smaller in size and less heterogeneous, they, nevertheless, give us perspective on the concept

of quality educational performance that is not burdened with direct cost applied to the student. The aim is not to replicate the educational models in these two countries or adopt them to the United States, since each country is

unique in its particularities. The aim, however, is to learn from these models and uncover through cost-benefit analysis that when cost of education is shifted directly from the citizen/student to indirectly toward the society, the emerging benefits will outweigh the associated cost and will be far greater than benefits gained to if cost is applied

directly to the individual citizen/student.

2. The education system in Sweden

In Sweden, the educational system is free of tuitions and fee cost to all citizens from kindergartens to universities (“Sweden education system and policy handbook”, 2009, pp. 12-22). Students have no direct obligation to cover the cost of their education and have free access to all levels of education supported by taxes

(Hudson & Lidstrom, 2002, pp. 36, 67-90). As a result, Sweden is considered as one of the world’s leaders in free-market education (Herve, 2008, p. 1; Wagner, 2006, p. 1).

Consequently, Swedish economy is thriving with collective actors (Schenk, 2007, p. 1) and excellence in global economic performance (Ryner, 2002, pp. 99-120). Swedish citizens equally enjoy the benefits of progressive social and labor programs for many decades (George & Taylor-Gooby, 1996, pp. 72-90; Rosenthal,

1967, pp. 3-12; Sebardt, 2006, pp. 64-69), such as universal healthcare (Anell, 2008, pp. 5-9), five weeks of paid vacation (Yanuck, 2003, p. 6), 15 months of paid maternity leave at 75% of salary (O’Neill, 2004, p. 1), and

civic engagement to hold transparent and accountable governance is very high (Milner & Ersson, 2000, p. 1). The Swedish Government’s domestic policy, as such, is dictated horizontally by citizen voices in most

aspects of life (Milner, 1985, pp. 15-39; Olsson, Nordfeldt, Larsson & Kendall, 2005, p. 1). There is no elitist mentality and the country’s foreign policy shies from military engagements or involvements in wars (Government Offices of Sweden, n.d., p. 1). This non-militaristic approach toward foreign policy is making Sweden one of the

most respected and admired countries in the world (Swedish Trade Council, n.d., p. 1). The basic formula for this success is Sweden’s recognition of education as a fundamental human right issue for all its citizens regardless of

income, gender, age or region.

3. The education system in Iraq

According to United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the educational

performance in Iraq prior to the 2003 Iraq War was considered as one of the best in the entire region (2003, p. 56). This is despite the problems of top-down administrative structure, centralized curriculum, lack of electronic and

state of the art teaching materials, low students/teachers inputs and inadequate teachers continuous training. The number of elementary, secondary and university students, as well as teachers and professors of both genders continued to increase (Asquith, 2003, p. 1). Government provided free public education through a centrally

organized school system that included a six-year elementary level and six-year of secondary level, and consisted of three years intermediate and three years of preparatory levels. Graduates of these schools were able to enroll

without paying for tuition, fees and cost of housing or books to any vocational and technical institutions, colleges or universities throughout the country (Iraq’s Ministry of Planning and Development Cooperation, 2005, pp. 8-12).

After the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, problems of corruption (Corn, 2007, p. 1), security, sectarianism,

kidnapping (O’Hanlon & Livingston, 2009, p. 1), attacking and killing of students, teachers and professors (Adriaensens, 2007, p. 1), absenteeism, internal migration and external displacement (International Rescue

Committee, 2008, p. 1) had collectively reduced Iraq’s educational performance to a lower standard. Adding to these problems were issues of insufficient school facilities, poor conditions of damaged school buildings and lack of clean water and electricity (Paley & DeYoung, 2007, p. 1). This is in addition to lack of labs, equipments,

teachers, staff, and outdated curriculum (Adriaensens, 2009, p. 1).

The invasion also created an environment for fraud in Iraq’s educational measures and exams (Khadduri,

2008, p. 1), increased the need for private tutoring (Issa, 2009, p. 1), and exacerbated the problems of inflation and unemployment. Collectively, these issues caused large number of educated Iraqis to either flee Iraq to other countries (Brulliard, 2007, p. 1) or forced them to accept work in unskilled fields, such as driving taxi cabs. In

Baghdad alone, for example, there are more individuals with Ph.D. working as taxi drivers than any other place in the world (Al-Shawi, 2006, p. 56).

When one compares Iraq’s educational performance under the regime of Saddam Hussein, a political system that many Iraqis regard as one of the most repressive political regimes in their modern history, with Iraq’s current educational performance under the watchful eye of the most powerful country on earth that prides itself as the

beacon of freedom and human rights, one wonders what is missing in this scenario? Why a brutal and repressive regime, such as that of Saddam Hussein, was able to deliver an educational system that had no matching in the

Various responses may be given to these questions. Perhaps the most obvious answer is the issue of security. When a country lacks in security, it cannot perform well in education. Both students and teachers are afraid to

attend classes due to threats of kidnapping and bombing. This is in addition to the deteriorating conditions of school building as a result of 20 years of wars and economic sanctions (Caroll, 2005, p. 1; Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2000, p. 1; Karadsheh, 2009, p. 1; Loyn, 2007, p. 1). Yet, lack of security as a

justification for poor performance in education is partially true and can be challenged if another situation presented itself with similar condition (lacking security) while demonstrating improved quality in educational

performance. An example of this exceptional scenario is the Kurdish educational system in Iraq.

According to Foreign Affairs, the Kurdish educational system in Iraq had suffered greatly because of conditions created by internal war and Saddam’s genocide campaign against the ethnic Kurds (Quandt, 1996, p. 1).

Yet, despite these difficult conditions, the Kurdish education system in Iraq continued to perform well, uninterrupted by displacement of Kurdish citizens, daily bombardment of Kurdish towns and villages, forced

migration of large number of Kurdish tribes, or economic sanctions imposed by the central government.

The Kurdish uprising of the 1970s, for example, made sure that schools in the Kurdish area under the control of Kurdistan Democratic Party, the political organization that led the Kurdish movement during that time, had

encouraged students to attend class regularly and continued with their education despite the hardship imposed by the internal civil war (Dawoody, 2006, pp. 10-11). The period of the 1998s-1990s witnessed internal fighting

between various Kurdish factions, mainly between militia groups belonging to Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (Stansfield, 2003, pp. 86-94). The Allied’ No-Fly-Zone and protection of the Kurds, however, helped stabilizing the Kurdish area and improve the Kurdish educational system to maintain

good quality performance (Zunes, 2007, p. 1).

Today, Kurdistan Regional Government asserts that the region of Iraqi Kurdistan has numerous universities,

technical institutions, elementary and secondary schools in most of the region. Kurdish students and professors are also taking part of international symposiums and conferences and engaging in study-abroad programs (Kurdistan Regional Government, n.d., p. 1). The New York Times reports that the American University has opened a new

campus in Iraqi Kurdistan on October 7, 2007 (Friedman, 2007, p. 1) and the Kurdish government is responsible for paying all costs associated with education from kindergartens to graduate schools (Kurdistan Regional

Government, n.d., p. 1).

It is evident here that when cost of education is shifted from students and schools to society, the overall quality of education and students’ educational performances will improve regardless of income, condition or

setting. Regrettably in today’s Iraq, only students who can afford private tutoring (Issa, 2009, p. 1) are performing well. This is creating disparities in the educational performance between those who can benefit from paying

private tutoring and those who are unable to do so. An emerging elites group is expected to surface in Iraq at the expense of a larger powerless group if such trend continues.

4. The education system in the United States

Education at all levels in the United States is mainly provided by public funds. Yet, there are numerous private educational institutions that compete with public education that are funded by contributions from parents,

performance (Geller, Sjoquist & Walker, 2001, p. 1; Kafer, 2004, p. 1). Because of this, students from various parts of the world are coming to the United States to persue their educational careers (Higgins, 2008, p. 1).

According to the Times Higher Education, some of the best learning institutions in the world, for example, are located here in the United States (“Top 200 world universities”, 2007, p. 1). Many American universities are considered the world’s leading research centers and many of their members are globally recognized through

prestigious awards, such as the Nobel Prize in the arts and sciences (US History, n.d., p. 1).

Yet, despite this trend in achievements, CBS News suggests that the United States lacks behind other

developed countries in education (Cosgrove-Mather, 2002, p. 1). Many American students, for example, especially in the first two levels of elementary and secondary education and in some college levels continue to exhibit problems in performance (Ravitch, 2009, pp. 284-319, 453-456; Tyack & Cuban, 1995, pp. 12, 110-140).

We are also witnessing an alarming increase in the production of large number of the under-educated (Toppo, 2005, p. 1), the unskilled (Harrison & Peevely, 2007, p. 1), and the drop-outs (United States Department of

Education-National Center for Education Statistics, n.d., p. 1; Dorn, 1990, p. 167; McKinsey, 2009, p. 1).

Unlike Iraq, we do not suffer from tyrannical government, forced migration, continuous wars, occupation, or lack of equipments and modern educational tools. And unlike Sweden, we are not exposed to large scale of

taxation. So, why do Sweden rank as fifth in global educational performance (Batty, 2009, p. 1) and Finland, a country that has similar educational system to Sweden as first, but we rank as 34th(Spencer, 2009, p. 1)?

In comparing our education system with that of Swedish and Iraq, it is evident that our education system whether public or private is expensive (Khullar, 2009, p. 1). The two-tiered social system is also impacting performance (McKinsey, 2009, p. 1). Public funding is limited (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2009, p. 1) and

strangled by ineffective bureaucratic policies such as “No Child Left Behind” (Aft.org, 2004, p. 1). Scholarships and grants are inadequate. Only a few can afford the high cost of education. Such cost is higher than many

developed nations, making the United States the 13th in the world in terms of educational affordability, with Sweden as the first (Usher & Cervenan, 2005, p. 1).

Perhaps we may continue producing doctors, lawyers, engineers, mathematicians, physicists and other

professionals if we continue with such a trend. Scholarships, grants, loans and family savings may continue offsetting some of the cost of public and private education. Collectively, however, are these are not adequate

answers to our problems. To begin with, we still have to remedy the inability of many Americans to have access to education. Second, we need to find a way to re-educate and re-train those who dropped-out and were unable to fully take advantage of our education system and remained unfit in a highly competitive world. Third, we need to

find a place for the growing army of the under-educated in our country without absorbing them in the military and force employing such an army through the manufacturing of unnecessary wars (such as the Iraq War of 2003).

Another issue to consider is the increasing absence of the wealthy and middle class from the military and the saturation of military forces with individuals from minority groups (Rangel, 2002, p. 1), the poor, and students who enlist to benefit from the GI bill in order to pay for the rising cost of education (United States Department of

Veterans Affairs, n.d., p. 1).

According to a study conducted by the University of Florida, the increase rate of producing an army of

under-educated and drop-outs is causing the United States to fall behind in global competition (Harris, Van Blokland & White, 2007, p. 1). In addition to militarization, the consequence of this problem is increased unemployment, under-employment and rise of economically-generated crime (such as theft, robbery, illegal drug

correction system (Ross, 2006, p. 1).

Alongside this alarming notion is the problem of the growing influence of the military industrial complex

(Raw Story, 2006, p. 1; Norris, 2009, p. 1). Such an industry is a war-profiteering system that President Eisenhower warned of its threat during his farewell address to the nation on January 17, 1961 (Eisenhower, 1961, pp. 135-140). By militarizing its economy and public policy and engaging in manufactured wars, the United States

is turning global opinion against it and presents itself to the world as a war-mongering nation (Milne, 2009, p. 1; Shank, 2007, p. 1). The United States is also providing extremist groups opportunities to use its

negatively-perceived image in order to monopolize sentiments and recruit terrorists to target American interests in the world (Lustick, Eland & Porter, 2008, p. 1).

5. Recommendations

Education in the United States must shift from the elitist mentality to a populist and egalitarian concept. Every American must have free access to education supported by combination of public funding, scholarships,

grants and philanthropies. Government must assure that public education is accessible without economic barriers, and provide adequate resources to all levels of education in order to assure the production of highly educated Americans at all levels and from all walks of life. There ought to be no tuitions, fees or any other costs associated

with education, especially in public sector. Students and parents need to focus on educational performance instead of focusing on where to get money to pay for the rising cost of education.

Public education does not eliminate private institutions. However, public education ought not to be second to private education and must continue to compete for excellence in performance while benefiting from adequate funding resources. The United States is the wealthiest nation on earth. If we, as a nation, are capable of devoting

trillion of taxpayers’ money to fund manufactured wars, then we are more than capable of providing adequate funds for good quality public education.

The main criteria for progress in education ought to be student performance instead of personal or parental income. In Sweden and Iraq, for example, any student graduating from high school can apply to any college or university and complete his studies free of charge (“Sweden education system and policy handbook”, 2009, pp. 12-22;

UNESCO, 2003, p. 56). Only two factors dictate the student’s educational track and progress: choice of discipline and GPA. We can learn from these models and exceed them in performance if we consider some of the following:

(1) Decentralizing our education system and leaving decisions to be made autonomously by each school district while benefiting from a network of collaboration, association and shared-expertise with other entities in the system. An autonomous school district within a collaborative network of association is an effective agent for

positive change. This model is best known as the agent-based model, whereby each unit in a system is autonomous, yet connected with other units (agents) in a network of collaboration and association (Gilbert, 2008,

pp. 2-6, 15-16).

(2) While supporting the autonomy of each school district, we need to revitalize and diversify the curriculum to correspond with changes in the world, teach to educate rather than teach to test, apply the learned concepts into

real life situations, and avoid the “one-size-fits-all” model.

(3) Aborting the transformation of our schools into factory-style in educational process. Instead, we need to

(4) Integrating educational responsibility beyond the school system to include parental and societal responsiveness and involvement.

(5) Continuing the use of technology, smart classrooms and visual equipments to support innovation in teaching methods.

(6) Continuing the improvement of teachers’ training and teaching, and expanding pedagogical and socratic

approaches toward learning through inquiry.

(7) Including other world views in our curriculum instead of concentrating on western orientations and

perspectives.

(8) Transforming the classroom from a static forum of routine recycling of cliches toward new laboratories of awakened and interconnected human epistemology.

(9) Departing from the linear methodology of observing a phenomenon (Strogatz, 1994, p. 326) and moving toward exploring the world through the prism of chaos (Holland, 1998, pp. 3-14), uncertainty (Prigogine, 1996, pp.

73-106), mutual causality and self-organization (Miller & Page, 2007, pp. 33-98). These new sciences of complexity can teach us think in multiple, nonlinear perspectives while entertaining mutual causality, network, and interconnectedness (Wheatley, 2006, pp. 17-20), instead of observing the world from an objective, rigid,

top-down, controlled, authoritarian and uniform centralized perspective.

(10) Celebrating subjectivity, uncertainty, shades of gray and self-organization (Wheatley, 2006, pp. 27-70).

(11) Learning ought to be measured through its applicability. What may appear to make sense in theory may not prove to do so if put into real life test. The experimentation of the neocons through the nation-building experiment in Iraq during the Bush administration is an good example of prioritizing abstract and unexamined

theory over learned experience (Lind, 2004, p. 1). The neocons’ theoretical justifications of the Iraq War, for example, and how Iraqis will welcome us with open arms if we toppled Saddam, how we can transform Iraq into

democracy and along with it the entire political map in the Middle East through the domino effect, proved to be nothing but a naive political abstract that quickly evaporated once it hit the ground (Baxter, 2006, p. 1; Medved, 2006, p. 1; Winston, 2007, p. 1).

(12) We no longer can see causality in a linear progression, predict or plan for an unforeseeable future (Waldrop, 1992, pp. 198-240), and hold-on to dying and outdated systems and structures and maintain them alive

through artificial engineering beyond their natural life cycle (Goldstein, 1994, pp. 39-70). Instead, we must embrace multiple perspectives and approaches toward observing a phenomenon (Wheatley, 2006, pp. 3-15). If a system is about to collapse and exhibits threshold leading to such tendency, as it was the case with our financial

investment system in 2008 after the emerging of the mortgage crisis, we ought to welcome this collapse and allow it in order for a new structure to emerge that is better equipped to deal with new changes in the environment.

Sustaining the older order to remain alive through artificial engineering (such as through infusing public funding into the decaying financial investment industry) will only delay its ultimate and unavoidable collapse by buying it some extra time. The difference, however, between a natural collapse and a delayed collapse caused by an

artificial engineering is that the latter will result in catastrophe and the former will result in the emergence of a more dynamic system (Kauffman, 1993, pp. 237-255).

(13) We need to realize and accept that our current education system is in a dire need for collapse and for a new dynamic system to emerge that is better capable in dealing with changes in the global environment. From the death of the current outdated system, the new system will emerge randomly and without control or artificial

6. Conclusion

Education is not the mere repetition of the same thing. Rather, education is an innovative and an on-going

process of learning and re-learning. As Piaget had demonstrated, the objective of education is to create people who are able to do new, innovative things (cited in Schmidt, 2006, p. 1), instead of repeating or recycling the same over and over again. We need also not to consider students as blank slates who lack inputs, perspectives or

experience. Galileo proved the fallacy of this by suggesting that we cannot teach a human being anything. Instead, we can only help him find it within himself (cited in “Good Reads”, n.d., p. 1).

Learning is a holistic concept. As the successful Swedish model had demonstrated, it involves the teacher, the student, the parents, governance and society as a whole. Our education system, regrettably, focuses on standardized tests that were introduced decades ago and lived out their use, applicability and function. Instead of

teaching to test, we must teach students to learn and comprehend the world. Instead of dictating abstracts and emphasize wider applicability. Instead of following the model of factory production processes, one-size-fits all,

standardized schedules, tasks and outputs, we need to pay attention to inputs, particularities, and the interconnectedness of issues, factors, subjects and players. And, instead of focusing on cost, we need to pay attention to improved performance in learning.

We must emphasize the need for creating new and innovative means for students’ learning. We need to encourage teachers to continue developing and expanding their areas of knowledge, expertise and teaching

methods while learning from other successful models in the world. A teacher cannot teach others unless he starts by teaching himself (Gibran, 1993, pp. 17-40).

Teaching oneself before teaching others while teaching by example requires thinking. Education and

classrooms must be laboratories for free thinking and transcend limitations. Memorizing theories and concepts without abilities to think on how to synthesize, apply, analyze, critique or arrive to alternative futures is fruitless.

The purpose of thinking is to contemplate better ways in understanding life and applying learning toward the improvement of all lives on earth. Thinking must lead to learning, and learning must lead to thinking. Both learning and thinking, according to Confucius, are the interconnected variables of one dynamics (cited in Leys,

1997, pp. 3-5.).

Learning institutions, however, are only means to facilitate learning and thinking. On their own, they are not

the medium for either learning or thinking. Emerson alluded to this by acknowledging that what we teach in learning institutions is not education but the means for it (cited in Emerson, n.d., p. 1). When these means become obstacles in front of learning and thinking, education seizes to deliver on its promise.

Outmoded structures in educational systems get in the way of learning and thinking. As Twain has warned, we do not need to allow for mundane schooling system to interfere with our education (cited in Vandermeer, 2005,

p. 1). Russell echoes Twain’s warning by stressing that we are made non-thinking individuals by means of improper education (cited in Spirit and Flesh, n.d., p. 1). Einstein adds to this observation by warning against the inadequacy of an education system in strangling inquiry and free thinking (cited in Eves, 1988, p. 31).

We need to promote free thinking and learning through innovative teaching and learning methods. We are unable to do so if we keep education accessible only to the few. We can ride the threatening tsunamis of inequality

by providing a threshold for the emergence of a new dynamic that can transform the republic into an egalitarian forum capable of allowing its entire citizen to compete and remain viable on a global level.

the facilitation of learning and thinking. We must also make sure that our educational system is dynamic and essential in the production of learned citizen-thinkers. This realization can be achieved through the provision of an

unburdened access to education through direct cost. This type of unconstrained access is a primary ingredient in the creation of an equalizer that will play as a “kick” in destabilizing an outmoded structure and help moving it toward its collapse and the emergence of something new and dynamic that is better capable in dealing with

changes in its environment.

This key ingredient that will kick the process forward toward the collapse of the current outmoded and

outdated education structure will play as an equalizer not only in making education accessible to all Americans but also in transforming the republic itself into a new egalitarian forum for equality and social justice. The kick will reshuffle the mundane structure in our education system to force its shift toward disorder, restructuring

through chaos new and a healthier emerging equilibrium that will bring us toward a new threshold in the creation of citizen-thinker in a knowledge-based egalitarian society.

We are writing our possible future today. Therefore, we need to consider education as a human right issue. Continuing on the current path without allowing for the key ingredient of unburdened access to education to play as a kick in changing the system will lead us to catastrophes and reduce our effectiveness in the world to mere

irrelevant existence. America’s strength rests in producing a new mantra that regards education as a fundamental human right. This understanding is vital for safeguarding the future of the republic.

References:

Adriaensens, D.. (2007, April 18). Iraq’s education system on the verge of collapse. Retrieved October 14, 2009, from http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=5429.

Adriaensens, D.. (2009, September 15). Iraq: Massive fraud and corruption in higher education. Retrieved November 2, 2009, from http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=15214.

Aft.org. (2004, July). NCLB: Its problems, its promise. Retrieved June 16, 2009, from http://www.aft.org/pubs-reports/downloads/ teachers/PolicyBrief18.pdf.

Allen, J.. (1997, May 2). Inequality of funding public education raises justice issues. Retrieved October 19, 2009, from http://natcath. org/NCR_Online/archives2/1997b/050297/050297a.htm.

Alliance for Excellent Education. (2009, June). Reinventing the federal role in education: Supporting the role of college and career readiness for all students. Retrieved November 6, 2009, from http://www.all4ed.org/files/PolicyBriefReinventingFedRoleEd. pdf.

Al-Shawi, I.. (2006). A glimpse of Iraq. Lulu.

Anell, A.. (2008). The Swedish health care system. Sweden: Lund UP.

Asquith, C.. (2003, November 4). Turning the page on Iraq’s history. Retrieved October 11, 2009, from http://www.csmonitor.com/ 2003/1104/p11s01-legn.html.

Batty, P.. (2009, October 9). Ranking 09: Asia advancing. Retrieved November 2, 2009 from http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk /story.asp?storycode=408560.

Baxter, S.. (2006, March 19). I was a Neocon: I was wrong. Retrieved September 15, 2009 from http://entertainment.timesonline.co. uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/article743213.ece.

Berube, M. R.. (1994). American school reform: Progressive, equity, and excellence movements, 1883-1993. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Brulliard, K.. (2007, May 5). Iraq reimposes freeze on medical diplomas in bid to keep doctors from fleeing abroad. Retrieved July 18, 2009, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/05/04/AR2007050402359.html?hpid=

topnews?hpid=topnews.

Caroll, J.. (2005, April 22). Iraq’s rising industry: Domestic kidnapping. Retrieved September 29, 2009, from http://www.csmonitor. Com/2005/0422/p06s01-woiq.html.

stories/2009/07/27/national/main5190593.shtml.

Chubb, J. E. & Moe, T. M.. (1990). Politics, markets and America’s schools. Washington, D.C: Brookings.

Corn, D.. (2007, August 30). Secret report: Corruption is “norm” within Iraqi Government. Retrieved September 13, 2009, from http://www.thenation.com/blogs/capitalgames/228339.

Cosgrove-Mather, B.. (2002, November 26). Poor Marks for U.S. education system. Retrieved October 5, 2009, from http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/11/26/world/main530872.shtml.

Dawoody, A.. (2006). Iraqi notes: A personal reflection on issues of governance in Iraq and US involvement. Public Voices, 8(2). Dawoody, A.. (2008). A complexity response to funding public education. The Innovation Journal, 13(3).

Dorn, S.. (1990). Creating the dropout: An institutional and social history of school failure. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. Duncan, A.. (2009, October 9). A call to teaching. Retrieved October 29, 2009, from http://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/2009/10

/10092009.html.

Eberts, R.W., Schwartz, E. K. & Stone, J. A.. (1990). School reform, school size, and student achievement. Federal Reserve Bank of Economic Review, 26.

Eisenhower, D. D.. (1961). Public papers of the presidents of the United States: Dwight D. Eisenhower. Washington, D.C.: GPO. Emerson, R. W.. (n.d.). Poet seers. Retrieved November 4, 2009, from http://www.poetseers.org/the_poetseers/sri_chinmoy/spiritual

_poetry/phil/emerson/.

Eves, H.. (1988). Return to mathematical circles. Boston: Prindle.

Fauth, R. C., Brady-Smith, C. & Brooks-Gunn, J.. (n.d.). Poverty and education-overview, children and adolescents. Retrieved July 16, 2009, fromhttp://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2330/Poverty-Education.html.

Federal Education Budget Project. (n.d.). No Child Left Behind—Title I distribution formula. Retrieved November 2, 2009, from http://febp.newamerica.net/background-analysis/no-child-left-behind-act-title-i-distribution-formulas.

Fogel, R. W.. (2000). The fourth great awakening and the future of egalitarianism. Chicago: U of Chicago P.

Friedman, T.. (2007, September 2). The Kurdish secret. Retrieved October 11, 2009, from http://select.nytimes.com/2007/09/02/ opinion/02friedmancolumn.html?_r=1.

Gabbard, D., Ross, A., Wayne, E., et al. (Eds.). (2004). Defending public schools. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Geller, C. R., Sjoquist, D. L. & Walker, M. B.. (2001, February). The effect of private school competition on public school performance. Occasional paper No. 15. Retrieved June 6, 2009, from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/ content_storage_01/0000019b/80/1b/32/92.pdf.

George, V. & Taylor-Gooby, P.. (1996). European welfare policy: Squaring the welfarecircle. NY: St. Martin’s. Gibran, K.. (1993). Wisdom of Gibran. New Delhi: UBS.

Gilbert, N.. (2008). Agent-based model. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Goldstein, J.. (1994). The unshackled organization. Portland, Oregon: Productivity.

Good Reads. (n.d.). Quotes by Galileo Galilei. Retrieved November 5, 2009, from http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/14190. Galileo_Galilei.

Government Offices of Sweden. (n.d.). Foreign policy. Retrieved November 2, 2009, from http://www.regeringen.se/sb/d/3103. Harris, D., Van Blokland, P. J. & White, J. K.. (2007, January). American education: Falling behind. Retrieved September 11, 2009,

from http://irrec.ifas.ufl.edu/files/student_work/ 06_12_Harris.pdf.

Harrison, R. E. & Peevely, G. L.. (2007). A center for technology-based decision-making in the economics of rural education. Retrieved October 11, 2009, from http://www.tnstate.edu/learningsciences/research/ed_funding.htm.

Headden, S.. (1997, October 12). Hispanic dropout mystery. Retrieved September 5, 2009, from http://www.usnews.com/usnews/ culture/articles/971020/archive_008077_2.htm.

Heller, D. E.. (2009, November 5). Stop financial aid for wealthy students. Retrieved November 8, 2009, from http://www. insidehighered.com/views/2009/11/05/heller.

Henry, W. A.. (1995). In defense of elitism. Anchor.

Herbert, B.. (2008, January 29). Investing in America. Retrieved September 11, 2009, from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/29/ opinion/29herbert.html.

Herve, N.. (2008, November 13). Learn and study together with other students from all over the world. Retrieved September 6, 2009, from http://www.kth.se/ict/utbildning/2.3165/2.3315/1.13311?l=en.

Higgins, S.. (2008, June 23). Coming to America: International students are flocking to area colleges and universities like never before. Retrieved July 9, 2009, from http://www.newhaven.edu/news-events/23095.pdf.

Hopkins, G.. (1998, November 16). Hard hat area: The deteriorating state of school buildings. Retrieved May 3, 2009, from http://www.educationworld.com/a_admin/admin/admin089.shtml.

Hudson, C. & Lidstrom, A.. (2002). Local education policy: Comparing Britain and Sweden. NY: Palgrave.

International Rescue Committee. (2008, March). Five years later: A hidden crisis: Report of the IRC Commission on Iraqi refugees. Retrieved July 11, 2009, from http://www.globalpolicy.org/images/pdfs/308ircreport.pdf.

Iraq’s Ministry of Planning and Development Cooperation. (2005, June 30). National development strategy 2005-2007. Retrieved September 5, 2009, from http://www.lgp-iraq.org/publications/index.cfm?fuseaction=pubDetail&ID=37.

Issa, S.. (2009, September 10). Another legacy of war: Iraqis losing faith in public schools. Retrieved October 16, 2009, from http://www.mcclatchydc.com/world/story/75196.html.

Kafer, K.. (2004, April 26). Refocusing higher education aid on those who need it. Retrieved May 11, 2009, from http://www.heritage.org/research/education/bg1753.cfm.

Karadsheh, J.. (2009, February 12). Sectarian violence continues with more bombings in Iraq. Retrieved August 29, 2009, from http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/02/12/iraq.main/index.html.

Kauffman, S. A.. (1993). The origin of order. NY: Oxford UP.

Khadduri, I.. (2008, March 30). The Iraqi Brian suction. Retrieved July 20, 2009, from http://www.iraqsnuclearmirage.com/ articles/The%20Iraqi%20Brain%20Suction.html.

Khullar, M.. (2009, September 13). World apart: How the American educational system is failing to prepare US youth to be competitive in the global economy? Retrieved October 2, 2009, from http://diversitymbamagazine.com/how-the-educational- system-is-failing-to-prepare-us-youth-to- be-competitive.

Kozol, J.. (1992). Savage inequalities:Children in America’s schools. NY: Harper.

Kurdistan Regional Government. (n.d.). News. Retrieved October 3, 2009, from http://www.krg.org/.

Lemann, N.. (2001, June 24). America’s new class system. Retrieved August 11, 2009, from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/ article/0,9171,1101960226-135534,00.html.

Leys, S.. (1997). The analects of Confucius. NY: Norton.

Lind, W. S.. (2004, March 3). Reality 1, Neo-cons 0. Retrieved August 7, 2009, from http://www.military.com/NewContent/ 0,13190,Lind_030304,00.html.

Loyn, D.. (2007, January 10). Iraq’s migrants from violence. Retrieved August 5, 2009, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/ 6193775.stm.

Lustick, I. S., Eland, I. & Porter, G.. (2008, April 15). Is the “war on terror” creating terrorism? Retrieved September 1, 2009, from http://www.independent.org/events/detail.asp?eventID=136.

Manning, S.. (1999). How corporations are buying their way into America’s classrooms. Retrieved October 16, 2009, from http://epicpolicy.org/files/CERU-9909-97-OWI.pdf.

McKinsey. (2009, April). Economic impact of the achievement gap in America’s school. Retrieved November 3, 2009, from http://www.mckinsey.com/App_Media/Images/Page_Images/Offices/SocialSector/PDF/achieve ment_gap_report.pdf.

Medved, M.. (2006, November 14). The end of the Neocons? At least get rid of the term. Retrieved September 11, 2009, from http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/story?id=2652131&page=1.

Miller, J. & Page, S.. (2007). Complex adaptive systems. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Milne, S.. (2009, November 7). US foreign policy is straight out of the Mafia. Retrieved November 8, 2009, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/nov/07/noam-chomsky-us-foreign-policy.

Milner, H. & Ersson, S.. (2000, April 14-19). Social capital, civic engagement and institutional performance in Sweden: An analysis of the Swedish regions. Retrieved July 6, 2009, from http://www.essex.ac.uk/ECPR/events/jointsessions/paperarchive/

copenhagen/ws13/milner_ersson.PDF.

Milner, H.. (1985). Sweden: Social democracy in practice. Oxford: Oxford UP. Neill, M.. (2003). Don’t mourn, organize! Retrieved August 14, 2009,

from http://www.rethinkingschools.org/special_reports/bushplan/nclb181.shtml.

Norris, F.. (2009, July 31). Why a recovery may still feel like a recession. Retrieved August 22, 2009, from http://www.nytimes.com/ 2009/08/01/business/economy/01charts.html?_r=1.

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2000, September 5). Human right impact of the economic sanctions on Iraq. Retrieved August 16, 2009, from http://www.humanitarianinfo.org/sanctions/handbook/docs_handbook/HR_im_es_iraq.pdf. O’Hanlon, M. E. & Livingston, I.. (2009, November 4). Iraq index: Tracking variables of reconstruction & security in post-saddam

index.pdf.

Olsson, L. E., Nordfeldt, M., Larsson, O. & Kendall, J.. (2005, October). The third sector and policy processes in Sweden: A centralised horizontal third sector policy community under strain.Retrieved September 11, 2009,from http://www.lse.ac.uk/ collections/TSEP/OpenAccessDocuments/3TSEP.pdf.

O’Neill, S.. (2004, August 11). Paid maternity leave. Retrieved October 9, 2009, from http://www.aph.gov.au/library/INTGUIDE/ ECON/maternity_leave.htm.

Paley, A. R. & DeYoung, K.. (2007, November 29). Iraq’s quality of life. Retrieved September 11, 2009, from http://www. globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/167/35693.html.

Prigogine, I.. (1996). The end of certainty. NY: Free Press.

Quandt, W. E.. (1996, May/June). Iraq’s crime of genocide: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds. Retrieved April 4, 2009, from http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/51980/william-b-quandt/iraq%C3%82%E2%80%99s-crime-of-genocide-the-anfal-campa ign-against-the-kurds.

Rangel, C.. (2002, December 31). Bring back the draft. Retrieved September 9, 2009, from http://www.nytimes.com/2002/12/31/ opinion/31RANG.html.

Ravitch, D.. (2000). Left back: A century of failed school reforms. NY: Simon.

Raw Story. (2006, June). Dollars, not sense. Retrieved September 23, 2009, from http://www.rawstory.com/news/2006/waxmanrpt. pdf.

Rosenthal, A. H.. (1967). The social programs of Sweden: A search for security in a free society. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P. Ross, J. I.. (2006, April 18). Jailhouse blues. Retrieved June 5, 2009, from http://www.forbes.com/2006/04/15/prison-jeffrey-ross_

cx_jr_06slate_0418ross.html.

Ryner, M.. (2002). Capitalist restructuring, globalization and the third way: Lessons from the Swedish model. NY: Routledge. Schenk, A.. (2007). Change and legitimation: Social democratic governments and higher education policies in Sweden and Germany.

Sweden: GbR.

Schmidt, C.. (2006). Scholarships keep siblings debt free. Retrieved October 15, 2009, from http://www.agriculture.purdue.edu/ Connections/spring2006/11_ag_student_scholarships_01.shtml.

Schneider, A. & Ingram, H.. (1993). Social construction of target populations: Implications for politics and policy. American Political Science Review, 87(2), 334-347.

Sebardt, G.. (2006). Redundancy and the Swedish model in an international context. NY: Kluwer.

Shank, M.. (2007). Chomsky on Iran, Iraq, and the rest of the world. Retrieved October 11, 2009,from http://www.fpif.org/fpiftxt /3999.

Sianesi, B.. (2003). An evaluation of the Swedish system of active labour market programmes. RetrievedNovember 3, 2009, from http://www.ifs.org.uk/wps/wp0201.pdf.

Spirit and Flesh. (n.d.). Alternative education versus conventional school: Knowledge, indoctrination, learning, and unlearning. Retrieved November 5, 2009, from http://www.spiritandflesh.com/bookAlternativeEducationSchoolLearningIndoctrination Conventi_religion_spirituality.htm.

Spencer, V.. (2009, May 2). How does Finland’s education become the best in the world? Retrieved October 6, 2009, from http://schoolmatters.knoxnews.com/forum/topics/how-does-finlands-education.

Stansfield, G. R. V.. (2003). Iraqi Kurdistan: Political development and emergent democracy. NY: Routledge.

Stone, G., Pirone, J. & Paxton, S.. (2008, November 7). High tuition costs students to drop out. Retrieved October 11, 2009, from http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/Weekend/story?id=6411422&page=1&page=1.

Strauss, W. & Howe, N.. (2005, October 21). The high cost of college: An increasingly hard sell. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved October 11, 2009, from http://chronicle.com/article/The-High-Cost-of-College-a/20600/.

Strogatz, S.. (1994). Nonlinear dynamics and chaos. Cambridge, MA: Westview.

Swedish Trade Council. (n.d.). Sweden is the world’s top nation brand. Retrieved November 6, 2009, from http://www.swedishtrade. se/sv/vara-kontor/afrika/nigeria/Vanliga-fragor/Swedish-Business-Commuity---SBC/Sweden-is-the-world39s-top-nation-brand/. Sweden Education System and Policy Handbook. (2009). Washington, D.C: IBP.

Times Higher Education. (2007). Top 200 world universities. Retrieved November 5, 2009, from http://www.timeshighereducation. co.uk/hybrid.asp?typeCode=144.

Toppo, G.. (2005, December 16). Survey finds 1 in 20 lack basic English skills. Retrieved August 17, 2009, from http://www. usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-12-15-literacy_x.htm.

Education. Retrieved August 19, 2009, from http://www.highereducation.org/reports/pa_core/core.pdf. Tyack, D. & Cuban, L.. (1995). Tinkering toward Utopia: A century of public school reform. Harvard UP.

United States Department of Education-National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). A first look at the literacy of America’s adults in the 21st century. Retrieved November 2, 2009 from http://nces.ed.gov/NAAL/ PDF/2006470.PDF.

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2003, April). Situation analysis of education in Iraq. Retrieved August 11, 2009, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001308/130838e.pdf.

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). Education programs. Retrieved October 11, 2009, from http://www.gibill.va. gov/GI_Bill_info/programs.htm.

University of Washington-Bothell. (2005, August 18). Study finds that school-funding loopholes leave poor children behind. Retrieved September 9, 2009, from http://www.crpe.org/cs/crpe/view/news/36.

US History. (n.d.). American Nobel Prize winners. Retrieved October 9, 2009, from http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h2007.html.

Usher, A. & Cervenan, A..(2005). Global higher education rankings.Retrieved November 2, 2009,from http://www. educationalpolicy.org/pdf/Global2005.pdf.

Vandermeer, J.. (2005, December 16). Education that unleashes the creative spirit. Retrieved August 1, 2009, fromhttp://www. unschooling.ca/jeremiah.htm.

Vedder, R.. (2005, September 1). Why aren’t public schools more like universities? Retrieved August 11, 2009, from http://www. foxnews.com/story/0,2933,168107,00.html.

Wagner, A.. (2006). Knowledge for the global economy. Retrieved October 5, 2009, from http://www.highereducation.org /reports/muint/MUP06-International.pdf.

Waldrop, M.. (1992). Complexity: The emergence science at the edge of order and chaos. NY: Touchstone.

Wenglinsky, H.. (2007, October). Are private high schools better academically than public high schools? The Center on Education Policy. Retrieved September 6, 2009, from http://www.cep-dc.org/document/docWindow.cfm?fuseaction=document.

viewDocument&documented=226& documentFormatId=3665.

Wheatley, M.. (2006). Leadership and the new science: Discovering order in a chaotic world. San Francisco, CA: Berrett. Winslow, R.. (2002). A comparative criminology tour of the World-Sweden. Retrieved October 5, 2009, from http://www-rohan.

sdsu.edu/faculty/rwinslow/europe/sweden.html.

Winston, A. T.. (2007, September 11). The Neocons are losing their war. Retrieved October 9, 2009, from http://blog.nj.com/njv_ paul_mulshine/2007/09/those_deep_thinkers_known_as.html.

Yanuck, D. L.. (2003). Sweden (many culture, one world). Mankato MN: Blue Earth.

Yudof, M. G.. (2002, March/April). Higher tuitions: Harbinger of a hybrid university? Retrieved May 29, 2009, from http://www. utwatch.org/finances/change_yudof_harbinger.html.

Zunes, S.. (2007, October 25). The United States and the Kurds: A brief history. Retrieved September 9, 2009, from http://www. fpif.org/fpiftxt/4670.

Anonymous electronic identity in cross-border and

cross-sector environment

Libor Neumann

(ANECT a.s., Prague 14000, Czech Republic)

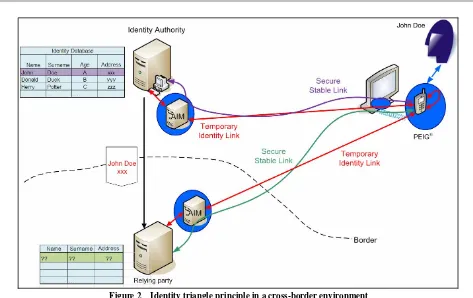

Abstract: The paper deals with identity management in cross-border and cross-sector communication in

e-government. The new ALUCID (automatic, liberal and user-centric electronic identity) technology based on new principles of anonymous and automatic identity enables markedly different and simpler identity management

with strong authentication support. This paper aims to compare ALUCID with PKI (public key infrastructure, a well-known identity management technology used in cross-border and cross-sector environment of e-government) from user’s and government’s point of view. It focuses on organizational aspects of eID issuing and verification,

various interoperability issues, language issues, legislative framework variety, cultural differences and privacy protection issues related to identity use and management. The specific features of the ALUCID technology which

was designed to support the specific needs of e-government in a cross-border and cross-sector environment are also described herein.

Key words: identity management; anonymous electronic identity; privacy protection; user centric eID; PKI;

ALUCID

1. Introduction

Cross-border and cross-sector communication in e-government is the most complicated area of identity management. The need of strong authentication, privacy protection as well as very complex relationships among a large number of government subjects and many citizens create a very complex environment.

Current technologies supporting strong authentication, which are applied in cross-border and cross-sector environment raise many significant issues, particularly in identity management: overcomplicated organization,

insufficient security (including privacy protection issues), interoperability issues, etc..

The new ALUCID technology is based on new principles of anonymous identity and enables markedly different and simpler identity management with strong authentication support.

2. Terminology

EID should be regarded as active electronic identity. By active electronic identity, we refer to the type of

electronic identity in which users (citizens) want to be recognized in electronic communication by a Relying Party (an electronic service provider). Passive identity, on the other hand, refers to situations in which citizens do not

want to be recognized (e.g., in crime).

Public key infrastructure (PKI) refers to organization framework that uses asymmetric cryptography based on

X.509 and related standards (e.g., IETF, 2010a, 2010b), i.e., organization framework which has certification authority as an essential component. Other organization frameworks using asymmetric cryptography (e.g., PGP

(Wikipedia, 2010)) are not considered to be part of the term in this paper.

Relying Party (RP) is a subject using eID technology (infrastructure) for its target activity (e.g., authentication). The term is used in a way that is usual in PKI. Typically, RP is an electronic service provider (e.g.,

an e-government service provider). The same term is used in ALUCID description to refer to the same subjects. The word “relying” does not fit very well in this case, though.

3. Basic PKI principles and fundamental features

The basic principles of the public key infrastructure (PKI) are as follows: (1) Personal information about the user is included in the certificate;

(2) The information is verified by a certification authority; (3) The RP finds the verified information trustworthy.

Certification authority is necessary to verify and sign information in certificates. The RP trusts the signed information; this information is open and can be read by anybody.

The fundamental features of PKI are described from 3 points of view: sequence of actions, data content and

change management. (1) Sequence of actions

The fundamental sequence of actions in PKI is:

(a) Processing personal information about the PKI user. The information is processed through user’s cooperation with a certification authority. The certificate is issued by the certification authority;

(b) Using PKI (the certificate with the private key). It is impossible to use PKI unless the certification process is successfully finished.

During the certificate life cycle, the first step is only made once. The second step is repeated many times. (2) Data content

The data content of the certificate is standardized (e.g., X.509 (IETF, 2010a)). However, the level of

standardization is insufficient, as it is possible to include the same information in several mutually incompatible ways. The real interoperability including semantic interoperability is not supported by the PKI standards.

RPs have to use the data content including the format and semantics in the way defined by the certification authority. The verification procedure is defined by the certification authority too. RPs and users thus depend on decisions of a third party.

All pieces of information in the certificate are readable for both machines and humans, and published to be available for everybody. The certificate with the included personal data is supposed to be public information.

There is no access right management in PKI; all data is available for everybody. (3) Change management

There is no change management of the data included in the certificate. The only way to modify the data is to

revoke the certificate and issue a new one. (4) Consequences

Compatibility and interoperability cannot be solved if it had not been solved before the certificate was issued. The quality of information in the certificate (and trust) is given before the certificate is issued.

4. Analysis of PKI features

PKI features depend on the environment in which the PKI is used. The situation that one RP directly communicates with one certification authority, especially if this certification authority is controlled by the RP, is

very different from the situation in which many hundreds of certification authorities are used by thousands of RPs in a multi-language, multi-cultural and multi-juridical environment. Cross-border and cross-sector environment is

a specific case of the second situation. 4.1 PKI in peer-to-peer environment

The peer-to-peer environment is the most frequent environment where PKI is used in real life. Typically,

specific electronic service providers create their own certification authorities and issue their own certificates. That means we can find one RP, one certification authority and one set of users in a very simple relationship.

The consequences are:

(1) One set of personal information is needed by the RP, only one set is used;

(2) The certification authority uses one verification procedure. This procedure is compatible with the needs of

the RP;

(3) The user can understand the need for information collection and verification done by the certification

authority for the specific RP. The relationship between the service offered by the RP and the certification procedure is understandable for the user;

(4) The user can understand and accept the need to collect and verify personal information before

authentication is used;

(5) Access right management (authorization) can be based directly on the personal information in the

certificate;

(6) Change management of the personal information in the certificate made by certificate revocation should be acceptable both for the RP and the user.

We know from the real world that this simple scenario is in use and can be successful. 4.2 PKI in cross-border and cross-sector environment

Cross-border and cross-sector e-government environment is very complex. It includes many RPs with very different needs and access right management based on different pieces of personal information. Tens of thousands of RPs exist in pan-European e-government environment. The spectrum of personal information needed for access

right management in different sectors of government is very wide: from a tax system, social security, health system, education, culture, agriculture, industry and trade, environment, transport and security to military systems.

The topology and law systems related to certificate authorities vary considerably from country to country. We can find one central certification authority managed directly by the national government, as well as a variety of non-government private certification authorities or even hundreds of local certification authorities managed by

local governments.

For PKI, this complex environment raises a number of additional issues. If we just take into account the

sharing of certification authorities by many RPs, we can find the following consequences: