Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in a Diverse Urban

Classroom

H. Richard Milner IV

Published online: 9 January 2010

Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010

Abstract While it is well established that the ability of teachers to build cultural competence is a critical aspect of their work especially in urban and highly diverse settings, the kinds of experiences that help them build cultural competence is less clear. The author attempts to contribute to this void by showcasing a White, science teacher’s experiences in building cultural competence in a highly diverse urban school. Culturally relevant pedagogy is used as an analytic tool to explain and uncover the ways in which the teacher develops cultural knowledge to maximize student learning opportunities. The basic premise of the article is that this White teacher was able to build cultural congruence with his highly diverse learners because he developed cultural competence and concurrently deepened his knowl-edge and understanding of himself and his practices. Practicing teachers, teacher educators, and researchers are provided a picture of how the teacher builds rela-tionships with his students, how he deepens his knowledge about how identity and race manifest in the urban context, and how he implements a communal and collective approach to his work as he builds cultural knowledge and cultural competence about himself, his students, and his practices.

Keywords Culturally relevant pedagogyCultureTeachingUrban

RaceContextTeacherDiverseScience

H. R. Milner IV (&)

Department of Teaching and Learning, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, Box 230, 230 Appleton Place, Nashville, TN 37203-5721, USA

Introduction

In this article, I use the conceptual framework, culturally relevant pedagogy,1as an analytic tool to examine the tensions, opportunities, and successes inherent in a White science teacher’s classroom practices in a diverse urban2 school. In particular, I revisit one of the tenets, cultural competence, of Ladson-Billings’ (2006) conceptualization of culturally relevant pedagogy in an attempt to build on and from it. The overall research questions that guided this study were: how was this teacher, Mr. Hall,3able to build cultural competence in ways that allowed him to (more) effectively teach his students? And in what ways does Mr. Hall develop relationships with his students inside and outside the classroom to build cultural competence? The basic thrust of the argument suggests that there are important features and decisions of this teacher—how he is able to bridge experiences with his students, to make important decisions on their behalf, and to work toward cultural competence—that can shed light on the complexities inherent in a White teacher teaching in a highly diverse urban context. Moreover, although Ladson-Billings stressed the fostering and maintenance of cultural competence for students, this study stresses the importance of teachers developing cultural competence to maximize learning opportunities in the classroom.

In an important chapter, Ladson-Billings (2006) shared the following regarding a representative interaction she had with a prospective teacher. The prospective teacher expressed the following concern to Ladson-Billings: ‘‘Everybody keeps telling us about multicultural education, but nobody is telling us how to do it!’’ (p. 30). Perplexing to many of those in her audience, Ladson-Billings’ response was ‘‘Even if we could tell you how to do it, I would not want us to tell you how to do it’’ (p. 39). For Ladson-Billings, there were at least two important lessons inherent to her response to the prospective teacher who queried about how to ‘‘do’’ multicultural education and essentially culturally relevant teaching. For one, teachers teach a range of students who bring an enormous range of diversity into the learning environment. There are no one-size-fits-all approaches to the work of teaching. Teachers must be mindful of whom they are teaching and the range of needs that students will bring into the classroom. Moreover, the social context that shapes students’ experiences is vast and complexly integral to what decisions are made, how decisions are made, and why. In short, the nature of students’ needs will

1 The term culturally relevantpedagogyis often used to discuss or describe the theory of culturally

relevant teaching while the term culturally relevantteachingis used to describe the practice of the theory. I will use both, pedagogy and teaching, interchangeably throughout this article because I recognize the interrelated nature of both.

2 There is not a static definition or meaning of the term ‘‘urban’’. Scholars define urban students, urban

environments, and urban education in varying ways. For instance, generally, urban education can be equated with inner-city schools or large metropolitan regions. Weiner (2003) noted that the literature paints a negative portrait of the urban context. She explained that lack of success in urban schools is often described as a result of the ‘‘problems in students, their families, their culture, or their communities’’ (p. 305). To suggest that all urban schools, neighborhoods, people, and other-related contexts are substandard would be unfairly inaccurate. There are some powerfully-rich knowledge, culture, and opportunity inherent in urban spaces; yet these resources are too often ignored and/or underexplored.

surely vary from year-to-year, from classroom-to-classroom, and from school-to-school.

A second point to Ladson-Billings’ response to the prospective teacher who complained that she was not being told how to ‘‘do’’ multicultural education is that no one tells us how to ‘‘do democracy’’ (Ladson-Billings2006, p. 39); we just do it. In a similar light, teachers who practice culturally relevant pedagogy do so because it is consistent with what they believe and who they are. Teachers’ conceptions guide their practices based on contextual realities and nuances inherent to and in their work. Teachers practice culturally relevant pedagogy because they believe in it, and they believe it is the right practice to foster, support, create, and enable students’ learning opportunities. Similarly, teachers (people) practice democracy for similar reasons. People are not told how to do democracy because democratic principles are infiltrated throughout US society. Ladson-Billings suggested that people practice democracy because they think and believe in its fundamental principles and ideals. Thus, more than a set of principles, ideas, or predetermined practices, the practice of culturally relevant pedagogy involves a state of being or mindset that permeates teachers’ decision-making and related practices.

In the subsequent sections of this article, I elucidate and discuss what I mean by culturally relevant pedagogy. Inherent in the discussion on culturally relevant pedagogy is a focus on outcomes and the central tenets of the theory. I then explain the methods employed in the study. The next section outlines the findings of the study, and in the final section, I provide implications and conclusions.

Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

Researchers have made a compelling case for the importance of developing culturally relevant curriculum and instruction for students, all students, in the P-12 classroom (cf., Foster1997; Ladson-Billings1994; Howard 2001). Gloria Ladson-Billings (1992), the scholar responsible for conceptualizing culturally relevant pedagogy, maintained that it is an approach that

serves to empower students to the point where they will be able toexamine critically educational content and processand ask what its role is in creating a truly democratic and multicultural society. It uses the students’ culture to help them create meaning and understand the world. Thus, not only academic success, but also social and cultural success is emphasized. (my emphases added) (p. 110)

uses student culture in order to maintain it and to transcend the negative effects of the dominant culture. The negative effects are brought about, for example, by not seeing one’s history, culture, or background represented in the textbook or curriculum…culturally relevant teaching is a pedagogy that

empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes. (pp. 17–18)

Educators who create culturally relevant learning contexts are those who see students’ culture as an asset, not a detriment to their success. Teachers actually use student culture in their curriculum planning and implementation, and they allow students to develop the skills to question how power structures are created and maintained in US society. In this sense, the teacher is not the only, nor the main arbiter of knowledge (McCutcheon2002). Students are expected and empowered to develop intellectually and socially in order to build skills to make meaningful and transformative contributions to society. In essence, culturally relevant pedagogy is an approach that helps students ‘‘see the contradictions and inequities’’ (Ladson-Billings 1992, p. 382) that exist inside and outside of the classroom. Through culturally relevant teaching, teachers prepare students with skills to question inequity and to fight against the many isms and phobias that they encounter while allowing students to build knowledge and to transfer what they have learned through classroom instructional/learning opportunities to other experiences.

Outcomes of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

One important question regarding culturally relevant pedagogy has to do with the relationship between culturally relevant pedagogy and student outcomes. That is, what are student outcomes when teachers create learning environments and pedagogical approaches that are shaped by and grounded in culturally relevant pedagogy? The answer to this question is not one that, I believe, can be answered by looking exclusively at students’ test score performance. Rather, the outcomes of culturally relevant pedagogy seem to extend far beyond what might be measured on a standardized exam. Grounded in Ladson-Billings ideology, as well as my own research, student outcomes can be captured in at least three broad categories— especially if readers are willing to think of student outcomes to be prevalent and possible beyond traditional test score measures.

One outcome of students who experience culturally relevant pedagogy is

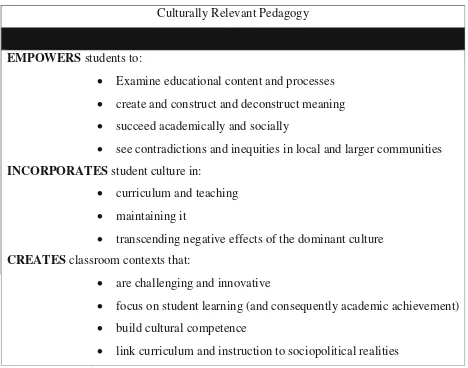

opportunities that are innovative and that allow them to meaningfullyunderstand the sociopolitical nature of society and how society works. In Fig.1, above, I attempt to capture and summarize some of the important outcomes—beyond results on a standardized exam—of culturally relevant pedagogy.

Tenets of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

Three interrelated tenets shape Ladson-Billings’ conception of culturally relevant pedagogy: academic achievement, sociopolitical consciousness, and cultural competence. Although Ladson-Billings has outlined the three main features of the theory, the theory has grown, developed, and evolved in some important ways. The theory—similar to theoretical orientations in education and other disciplines— has taken on multiple and varied meanings, depending on who is using it and for what purpose. Ladson-Billings (2006) expressed her regret for using the term academic achievement when she first conceptualized the theory partly because educators immediately equated academic achievement with student test scores. It is important to note that, as outlined in the previous section on outcomes, I have purposely expanded my conception of the outcome notion. What Ladson-Billings actually envisioned was that culturally relevant pedagogy would allow for and facilitate student learning: ‘‘what it is that students actually know and are able to do as a result of pedagogical interactions with skilled teachers’’ (Ladson-Billings2006, p. 34). Academic achievement, then, is about student learning. The idea is that if students are learning then they will be able to produce the types of outcomes, such as on standardized (high stakes) examinations, that allow them to succeed academically.

A second tenet of culturally relevant pedagogy according to Ladson-Billings is sociopolitical consciousness. Sociopolitical consciousness is about the micro-,

Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

EMPOWERS students to:

• Examine educational content and processes

• create and construct and deconstruct meaning

• succeed academically and socially

• see contradictions and inequities in local and larger communities

INCORPORATES student culture in:

• curriculum and teaching

• maintaining it

• transcending negative effects of the dominant culture CREATES classroom contexts that:

• are challenging and innovative

• focus on student learning (and consequently academic achievement)

• build cultural competence

• link curriculum and instruction to sociopolitical realities

meso-, and macro-level matters that have a bearing on teachers’ and students’ lived experiences and educational interactions. For instance, the idea that the unemploy-ment rate plays a meaningful role in national debates as well as in local realities for teachers and students would be centralized and incorporated into curricula and instructional opportunities to enable both teachers and students’ levels of consciousness. Ladson-Billings (2006) stressed that this tenet is not about teachers pushing their own political and social agendas in the classroom. Rather, she indicated that sociopolitical consciousness is about helping ‘‘students use the various skills they learn to better understand and critique their social position and context’’ (p. 37).

It is Ladson-Billings’ third tenet, cultural competence, that shapes the focus of this article. For Ladson-Billings, cultural competence is not necessarily about helping teachers develop a set of static information about differing cultural groups in order for teachers to develop some sensitivity towards another culture. Rather, for Ladson-Billings, cultural competence is about student acquisition of cultural knowledge regarding their own cultural ways and systems of knowing society and thus expanding their knowledge to understand broader cultural ways and systems of knowing. Such a position, Ladson-Billings explained, with a focus on cultural competence being on students runs counter to the ways in which other disciplines such as medicine, clergy and social work may think about and conceptualize cultural competence. In medicine, for instance, physicians are sometimes trained to develop a set of information about differing cultural groups to complement their ability to work with people who may be very different from them. For instance, it seems viable and quite logical for younger physicians to be educated to work with older patients. Bedside manner for physicians might also be enhanced when they develop knowledge about people living in poverty or people from a different racial or ethnic background from the doctor. The notion that physicians are attempting to deepen their knowledge-base about cultural groups for which they have very little knowledge and understanding can serve as essential knowledge for physicians as long as they realize the enormous range of diversity inherent within and among various cultural groups of people.

Where race is concerned, people sometimes misuse the term culture by collapsing all individuals in a particular race together. To illuminate, the term African American4denotes an ethnic group of people—not a singular, static cultural group; there is a wide range of diversity among and between African Americans although there are some consistencies as well. African Americans share a history of slavery, Jim Crow, and other forms of systemic discrimination and racism that bind the group. At the same time, African Americans possess a shared history of spiritual grounding, tenacity, and resilience through some of the most horrific situations that human beings have had to endure. However, while there are shared experiences, there are also many differences between and among African Americans. Take, for example, the variance between former Secretary of State Condelesa Rice and current National Football League (NFL) player, Michael Vick (currently playing for the Philadelphia Eagles). The differences between these two African Americans are

significantly greater than and beyond those of gender or perhaps political affiliation. While Rice and Vick are both African American and share some similarities between them, there are countless differences as well. A risk of such training, where physicians acquire knowledge about varying cultural groups toward cultural competence, is reifying stereotypes (Ladson-Billings2006).

Thus, what Ladson-Billings means by cultural competence is ‘‘helping students to recognize and honor their own cultural beliefs and practices while acquiring access to the wider culture, where they are likely to have a chance of improving their socioeconomic status and making informed decisions about the lives they wish to lead’’ (p. 36). In culturally relevant pedagogy, cultural competence seems to concern the ability of teachers to help foster student learning about themselves, others, and how the world works in order to be able to function effectively in it and also how to contribute to their communities. Building cultural knowledge, for students, from Ladson-Billings’ perception also has a goal of self and collective knowledge in order to challenge and transform power structures. The idea is that in order to have a seat at the table and to be able to participate in discourses of those in power (Freire1998), one must deeply understand who those in power are, and they must understand their own relationship to those in power.

In this article, I build on this notion of cultural knowledge and shift the focus from the specified focus on students to that of teachers. In other words, I argue that teachers need to build cultural competence in order to effectively teach their students, particularly in urban spaces. In the subsequent sections of this article, I analyze the practices of a White, male, science teacher in his attempts to build cultural competence in a highly diverse urban school. I turn next to discuss my own positioning with/in the study.

Situating Myself with/in the Study

Throughout the representation and discussion of the evidence from this study, I use first person. I use first person because, in a sense, I am telling my own story as much as I am reporting on the practices of Mr. Hall. As an African American, male researcher and a former secondary English teacher in a predominantly Black secondary school in the US who has attempted to build (and who continues to build) cultural competence, I wanted to understand how this teacher was able to build cultural competence with his students with a goal of maximizing students’ opportunities to learn. Moreover, as an African American male teacher educator and researcher, I consistently struggle with how to address, study, and write about race in my work. Because I am studying a White teacher’s practices and capacities to build his cultural competence in this study, I attempt to explain some of the tensions embedded in the practices of studying a participant outside my own racial and ethnic background. Is it appropriate for me to study matters of race with this teacher?

these tensions of positionality and my research elsewhere (Milner2007). As I was attempting to understand Mr. Hall’s experiences in developing cultural competence, I was also attempting to more fully and meaningfully understand my own, both as a high school teacher and currently as a teacher educator/researcher. To be clear, I remained true to the data and evidence in the study, but I also make explicit my goals, rationales, and thinking in posing questions and during observations. I agree with Kerl (2002), who wrote, ‘‘We cannot necessarily know what is true or even real outside our own understanding of it, our own worldview, our own meanings that are embedded in who we are’’ (p. 138) as outsiders and insiders. In the next section, I discuss, in more depth, my decisions and rationales in selecting the research methods, school, and the participant in the study.

Methods

Building on and from the qualitative research of others (Howard 2001; Ladson-Billings1994), I have been conducting research at Bridge Middle School for two academic years, approximately 19 months. I began conducting research at Bridge in September of 2005. The teacher in the study was nominated by the principal in the school. Broadly, I wanted to learn about, study, and hear the stories of teachers at Bridge Middle School and to understand and describe how and why teachers succeeded there. As my time at Bridge evolved, I focused in on how teachers developed cultural knowledge and competence to teach effectively in the school. Accordingly, I was also interested in the teacher’s struggles; what issues did he experience in the school and in his classroom with students that can shed light on the complexities of teaching and learning in an urban and diverse school? In what ways were this teacher’s struggles and successes contributory to his building of cultural competence? Moreover, I was interested in how the teacher managed his classrooms, how he was able to get parents involved, and how (in terms of curriculum and pedagogy) the teacher was able to make decisions about learning opportunities for his students, all students.

I conducted observations in what Rios (1996) called the cultural contexts of the teacher’s classrooms as well as other contexts in the school building. I also analyzed documents and artifacts and conducted interviews with the teacher. Throughout the study, I attended and observed the teacher’s classes, attended other school-related activities, events, and spaces such as the Honor Roll Assembly, the library, and the cafeteria. I wanted to learn as much as possible about the context of the school to provide rich and deep details about the nature of the school, its culture, and the teacher. I wanted to know what life was like for the teacher in the study, other teachers, and students not only in the classroom but also in other locations in the school. In short, I attempted to gauge, from a general perspective, the culture of Bridge Middle School as I attempted to understand how the teacher in the study was able to build cultural competence.

to gain an understanding and knowledge base relative to his work, thinking, and development. Although I participated in some of the classroom tasks, I was more of an observer than a participant. In some cases, I participated in group discussions and assisted with some minor laboratory experiment, for instance. Most of the time, however, I observed and recorded field notes in my field notebook related to the interactions I observed between Mr. Hall and his students.

I conducted semi-structured interviews (Denzin & Lincoln1994; Seidman1998) with the teacher individually, which were tape-recorded, transcribed, and hand coded; these interviews lasted 1–2 h. Although not tape-recorded or transcribed, I conducted countless informal interviews with the teacher where I recorded notes in my field notebook. Interviews typically took place during the teacher’s lunch hour or planning block. The hand coded analysis followed a recursive, thematic process; as interviews and observations progressed, I used analytic induction and reasoning to develop thematic categories. What is outlined in the subsequent sections of this article are representative of the kinds of information shared with me and that I observed from the participant. Because findings were based largely on both observations and interviews, the patterns of thematic findings emerged from multiple data sources, resulting in triangulation. This triangulation was central in data analysis. For instance, when the teacher repeated a point several times throughout the study, this became what I called a pattern. When what the teacher articulated during interviews also became evident in his actions or in his students’ actions, this resulted in what I called a triangulational pattern.

Bridge Middle School

Constructed in 1954, Bridge Middle School is an urban school in a relatively large city in the southeastern region of the United States. According to a Bridge County real estate agent, houses in the community sell for between $120,000 and $175,000. There are also a considerable number of rental houses zoned to the school. Many of the neighborhood students from higher socio-economic backgrounds and who are zoned to Bridge attend private and independent schools in the city rather than attend Bridge Middle School.5A larger number of students from lower socio-economic backgrounds attend the school. Bridge Middle School is considered a Title I school, which means that the school receives additional federal funds to assist students with instructional and related resources. During the 2006–2007 academic-year, Bridge Middle School accommodated approximately 354 students. The most recent data available regarding student demographics (2005–2006) indicated that 59.8% of the students at Bridge were African American, 5.6% Hispanic American, 31.6% White, .3% American Indian, and 2.8% Asian American, a truly diverse learning environment at least in terms of racial and ethnic diversity. The free and reduced lunch rate increased over the last four to 5 years, between the 2002 and 2006 academic years: 64–79%, respectively. In 2006, there were 27 teachers at the school with 45% of the faculty being African American and 55% being White. Seven of the

5 The practice of students attending magnet, private, and independent schools rather than their zoned

teachers were male and twenty were female. Figures2, 3, and 4 capture and summarize these important data regarding the school culture.

I selected Bridge Middle School because it was known in the district as one of the ‘‘better’’ middle schools in the urban area—relatively speaking. For instance, I asked practicing teachers enrolled in my classes at the university to community nominate (Ladson-Billings1994) what I called ‘‘strong’’ and some of the ‘‘better’’ urban schools. Bridge Middle School was consistently nominated. People in the supermarket would also mention Bridge as one of the better schools in the district upon my queries. When I met with a school official at the district office in order to gain entry into a strong urban school that had celebrated some success, he also suggested Bridge as a place to work.

Bridge Middle School is known for competitive basketball, wrestling, track, and football teams. The school building is brick, and windows at the school are usually open during the summer and spring seasons. There is a buzzer at the main entrance to the school. Visitors ring the bell, are identified by a camera, and are allowed in by one of the administrative assistants in the main office. When I visited the school, I signed a logbook located in the main office and would proceed to the teacher’s classrooms, to the cafeteria, or to the library. During my first month of conducting this research (September, 2005), one of the hall monitors insisted that I go back to the main office to get a red name badge, so I could be identified as a visitor/ researcher. They were serious about safety at the school. The floors in the hallways of the school were spotless. There was no writing or graffiti on the walls. Especially

African-American

White

Hispanic-American

Asian-American American-Indian

Total # of

Students

59.8% 31.6% 5.6% 2.8% 0.3% 354

Fig. 2 Students at bridge middle school 2006–2007

Ethnic Background Percentage African American 45%

55% e

t i h W

Fig. 3 Teachers at bridge middle school, 2006–2007

2002 Increase 2006

64% 15% 79%

during the month of February (2006 and 2007), Black history/heritage/celebration posters and bulletin boards occupied nearly all the wall space in the hallways.

Mr. Hall

The teacher in this study, Mr. Hall, is a White male science teacher who had been teaching for 3 years at Bridge Middle School. In 2008, Mr. Hall was nominated and selected by his colleagues as the Teacher of the Year for Bridge Middle School—a major feat for a teacher in the profession for so few years. Mr. Hall always dressed in blue jeans or khakis and a polo-style shirt. Throughout my 2 years of study at Bridge Middle School, I never saw, witnessed, or observed Mr. Hall taking a break. During his planning block, he was in his classroom preparing for the next class: cleaning lab supplies, grading papers, or writing on the board. During an assembly that I attended, Mr. Hall sat with his class and was constantly making sure that students were being respectful to their classmates while other teachers seemed to take a bit of a break.

Building Cultural Competence

In this section, I discuss what I was able to determine about Mr. Hall’s experiences in building cultural competence at Bridget Middle School. I attempt to display the mindset and the practices that were integral to this process. I attempt to capture Mr. Hall’s mindset in light of Ladson-Billings’ (2006) supposition that culturally relevant pedagogy is more about a way of being than a specified set of practices. The practices I share seemed to be shaped by the reality that Mr. Hall’s mindset, his thinking, and his belief systems shaped his ability to build cultural competence. I focus on three recurrent themes that seemed to capture Mr. Hall’s mindset and experiences related to building and practicing cultural competence:

• Mr. Hall was able to build and sustain meaningful and authentic relationships

with his students, which allowed him to build cultural competence in the classroom because the solid relationships allowed him to learn from/with his students.

• Mr. Hall recognized the multiple layers of identity among his students and

confronted matters of race with them. These interactions helped him build cultural competence.

• Mr. Hall perceived teaching as a communal affair; he worked to create a culture

of collaboration with colleagues and considered all students in the context his responsibility—not only those in his classroom. Mr. Hall was not only learning from students in his classroom, he was learning from those outside of his classroom; he was learning from his colleagues, which also seemed important in his building cultural competence.

Relationships

One important feature of Mr. Hall’s building of cultural competence centered around relationships. He appeared to understand the importance of building and sustaining relationships with his students at Bridge Middle School in order to deepen his knowledge about his students. In many ways, the building of relationships served as a precursor to learning what was necessary about others (his students mostly) as well as himself. He worked to build solid and sustainable relationships with each of his students as individuals as well as in the collective. In an interview, he stated:

I think that you have to develop a relationship witheach student. Every kid that you have has a different story and if you show interest in what they’ve (sic) gone through, they’re going to show interest in what you’re trying to convey to them. Then they will show interest in what you’re doing [in the classroom].

Paying careful attention to the needs of each student seemed paramount to Mr. Hall’s philosophy, thinking, and practices related to relationship building. He understood that there would be situations where he would need to address and learn from students as individuals and also in the collective. For instance, the development of cultural competence through his relationships with students served as a way for Mr. Hall to keep students in the classroom rather than sending them out with office referrals when (inevitably) conflicts emerged. In fact, Mr. Hall was known for providing students with multiple opportunities for success and for ‘‘trusting’’ students to ‘‘get it right’’ the next time rather than referring students to the office. He was not a teacher who was constantly sending students outside the classroom due to conflicts and disruptions. For instance, Mr. Hall did not necessarily send students to the office because they were tardy to class or due to other infringements that can cause teachers to refer students to the office. When students were not engaged in learning or when they misbehaved, he did not want to place their destiny in the hands of another (see, Monroe & Obidah2004, for more on this topic)—such as in the hands of an administrator who had the power to suspend or even expel a student from school. Again, his mindset and practices that were built and sustained through his relationships with his students precluded his wanting to jeopardize students’ education by referring the students to the office. Clearly, the kind of learning that is necessary for learning and achievement is not taking place when students are not in the classroom. Thus, Mr. Hall resolved to meet the students were they were, work with them, and develop the kinds of relationships with the students such that he could handle the pedagogical and management needs and demands inherent in the space.

‘one-size-fits-all approach’ to teaching and learning because he had developed some deep knowledge about the students themselves and their specific needs. How was Mr. Hall able to be responsive to each student as an individual and how was his responsiveness central to his building cultural competence? When asked how he responded to people who questioned his approach—looking at each student, relying on the relationships he had established with his students as individuals, and paying special attention to the idiosyncrasies of the situation–, Mr. Hall shared:

Well I’d ask: who hasn’t gotten a second chance in life? I mean everybody messes up and not everybody messes up at the same time. So I meanit’s a different situation for everybody. I mean, I know there are times in my job that I said the wrong thing, did the wrong thing, and…alarms didn’t go off, and the

swat team didn’t come in (my emphasis added)…People, my peers–people

above me pulled me aside and said: ‘Hey, you know, we don’t do it this way.’ You know I wasn’t terminated on the spot…You know I’m not going to [give

them failing] grades or hurt their self-esteem right there on the spot just because they did it wrong that time…Everybody’s different, you know…We

are not robots…we can’t all just crank out the same stuff every time. It’s going

to take one kid five times to get it…and it’s going to take one kid one time.

Mr. Hall had developed care and concern for his students through his relationships with them. He wanted to ensure that each of his students was able to master the information he was presenting (whether it be subject matter or rules about ways of conducting themselves), and he wanted the students to remain in the classroom. In essence, Mr. Hall was developing relationships with his students by not giving up on them, by not allowing the students to give up on themselves, and by not sending the students out of the classroom immediately when they ‘‘misbehaved.’’ This means that he allowed his students multiple opportunities to turn in work and that he would explain a concept repeatedly to make sure his students, all students, were learning:

Maybe that’s bad—[that] I give so many second chances–that I care about them too much, but I think it works for me. And I wouldn’t know how else to do it. And I couldn’t be one of those who say: ‘uh oh Timmy you didn’t get your homework done, well that’s your fifth zero.’ You know I couldn’t be like that.

The students mattered to Mr. Hall, and this showed up in the curricula, instructional, and management decisions he made. However, while there was not an overwhelming number of conflicts and incongruence that occurred in the learning context, there were times when Mr. Hall had conflicts with his students. It would be misleading to suggest that Mr. Hall did not encounter problems in his classroom context, as is the case in classrooms in all learning milieus. It is not the goal of this article to present a romanticized version of what life was like for Mr. Hall at Bridge Middle School. In a sense, the conflicts that emerged in the classroom were foundational to the types of relationships he would eventually build with his students. Mr. Hall’s ability to understand and work through the conflicts that he encountered with his students was instrumental to his building cultural competence. He needed to understand some of the differences and tensions between himself and his students in order to gain cultural knowledge. Thus, conflict, in this sense, was not a pejorative. By way of example, Mr. Hall expressed:

[There was a student]–He was a foot and a half taller than me, a big old guy. He wanted to chitchat and talk about sports and basketball and stuff, and he didn’t like me (sic) coming up to him telling him ‘‘get on task,’’ ‘‘get on task’’ [during labs] every 5 min. And one day he stood up to me and just went off. And I went off [too]—you know—it’s like two brothers fighting. He let me know what he was thinking. And I let him know what I was thinking, and we went our separate ways…it took us about a week, but one morning he just

walked up to me, and said, ‘‘We’re cool now.’’ It was almost like, ‘‘I didn’t know what happened.’’ I was cool from the minute he walked out the door. That’s just me: I am going to tell you how I feel, what I didn’t like, and I am done.

Mr. Hall explained that he had to constantly set the parameters in the classroom so that students realized that he wanted and expected them to do their best work at all times while he also was being open to his students and providing them multiple opportunities for success. At the same time, he was not willing to negotiate learning for nonsense in the classroom. Because Mr. Hall demonstrated a level of care that the students could sense, he was able to develop relationships with them that allowed for conflicts to emerge such as the one described above when the student wanted to talk about sports rather than focus on lab work. At the same time, Mr. Hall would not allow the conflict to overshadow what was most important: students’ opportunities to learn in the classroom. Thus, in the example above, the student was willing to give Mr. Hall a second chance when he walked up to Mr. Hall declaring: ‘‘we are cool now.’’ Mr. Hall had modeled the importance of giving others’ another opportunity, and the student adopted this approach with Mr. Hall.

While conflict was inevitable and even necessary for Mr. Hall to build relationships and consequently cultural competence, Mr. Hall shared examples of how building relationships did not always naturally occur. He asserted:

football team. And every week I was asking him ‘Hey how you doing [with basketball]? Did you score a basket?’ What did you do in the game?

As for the relationship between Mr. Hall and Paul, it took some serious work– relationship building–in order to increase Paul’s engagement, participation and ultimately learning in the science classroom. Mr. Hall took an interest in Paul outside of the school (in athletics) in order to build a solid relationship with Paul and ultimately to get him more involved with his academics. He stated

I’ve gone down to a couple of basketball practices and played one on one against him [with Paul], and he missed two assignments the whole year in homework. And his grade–average wise last year is up about fifteen points. He’s gone from being a C student in my class to being an A student. He’s just one example of how you show interest in a kid and how their output goes up in your class.

Mr. Hall clearly credits his student’s (Paul) increased participation, engagement, and grade in the classroom to the building and maintenance of a solid relationship with the student, one that demonstrated an interest in the life world of Paul in basketball. Mr. Hall was building cultural competence about his student and was also learning about ways to connect with other students in similar situations. Moreover, in building cultural knowledge about Paul, Mr. Hall took some responsibility for Paul’s lack of engagement in his class, and he worked to circumvent this by building a relationship with Paul outside of the classroom on the basketball court. Mr. Hall realized that in some cases, he would have to gobeyond

the walls of the classroom to build a meaningful relationship with the student in order to connect to and converge with the studentsinthe classroom. As for Mr. Hall, he attended Paul’s basketball practices and played against him one-on-one. The idea is that Paul probably began to see Mr. Hall in a different light on the basketball court; he started to see Mr. Hall as a real person who could shoot basketball and also who demonstrated enough care to take time out after school to play him in a few basketball contests. In addition to relationships, Mr. Hall’s ability to recognize the various layers of his and his students’ identity and to confront and address the salience of race in his classroom also contributed to his cultural competence.

Recognizing Identity, Confronting Race

Mr. Hall talked about how when he first became a teacher at the school, the students ‘‘didn’t know’’ him. In his words,

[The students would say:] ‘I don’t care who you are. I don’t know you.’ And then after year one you’ve had half of them…And they’re like okay well I

know he’s going to do this if I do this. So they start telling the seventh graders, Mr. Hall is going to get you if you do this…And then year three, you have

more of them. And your reputation has now spread down to the sixth graders.

that they ‘‘did not know’’ the teacher and if they did not feel that their teacher knew them as students with multiple and varied identities. Based on my observations and even in conversations with students in other classes and in other contexts in the school such as in the cafeteria, Mr. Hall was a teacher whom the students felt like they had come to know. Of course, this coming to know took time as Mr. Hall was building cultural competence based on what the students expressed to him and also based on what they expected of and from him: the students expected Mr. Hall to ‘‘know’’ them, and they needed to ‘‘know’’ Mr. Hall. Based on what he began to notice about the culture and expectations of his students, Mr. Hall believed that he had to facilitate opportunities for the students to get to know him. For instance, in the cafeteria, I would ask the students if they were taking a course from Mr. Hall, and I would ask for students’ impressions of him, his teaching, and his class in general. The students would tell me what was on their minds about Mr. Hall (and also other teachers—with very little probing), both positive and negative. As for Mr. Hall, the students saw him as ‘‘cool’’ and a ‘‘good teacher’’ as they had gotten to know him. At the same time, they perceived his class as ‘‘hard’’ but ‘‘fun.’’ The students would comment on how Mr. Hall always watched the Discovery Channel, and the students had developed an appreciation for the channel as well. In class, students quite often would reference a recent episode from the network, and Mr. Hall was right there with them, detailing the specifics of an episode and providing relevance to the science curriculum. The students and Mr. Hall had found a television channel that was somewhat of abridgeto learning in the classroom. In essence, Mr. Hall was able to build cultural competence based on his willingness to listen to and hear from students who complained that they did not ‘‘know’’ him. He discovered that many of his students were not willing to learn from him because they did not feel that they knew him and accordingly felt disconnected to him and the classroom experience.

professional/teaching identity. In some sense, Mr. Hall’s identity exposure was a prerequisite and a critical element for his students to feel that they had gotten to know him and to thusly engage in the teaching and learning exchange.

Eventually, Mr. Hall acted as an ‘other father’ to the many students with whom he taught throughout the day. Research suggests that successful teachers of culturally diverse students adopt parental/surrogate roles with their students (Irvine

2003). Similarly, Mr. Hall wanted what was best for the students, and he demonstrated this by building caring relationships with them but also by being strict enough to not allow them to get away with things that would be destructive or disadvantageous to or for them:

One thing I try to let kids know this year is that I really do care about them, you know, whenever I see them. You know, I love you. I want to see you play basketball. I want graduation invitations. You know, that’s not going to happen though, if you don’t straighten up in class. And I’ve tried to be more expressive, but at the same time, stay on them.

In addition, Mr. Hall explained that developing and sustaining positive relationships with students meant that teachers did not hold grudges against students. Mr. Hall shared that when students walk back into the classroom after a misunderstanding with him from the previous day, he did everything in his power to move forward and not to hold the previous day against the student. Mr. Hall recognized the complexities and the multilayered nature of the students’ identities, and he understood that developmentally, many of the students were grappling with peer pressure; he was determined not to take conflicts and misunderstandings in the classroom that emerged as personal attacks against him as the teacher. He stated: ‘‘If I get upset at you or if you screw up…tomorrow is going to be new. I’m not even

going to mention it. Unless you do the same thing…Everyday is a new slate.’’ The

idea is that teachers allow students another chance for success and do not expect the student to ‘‘make up’’ for their shortcomings and mistakes in the past. Each day, for Mr. Hall and his students, is a new day with new possibilities for success in the learning context. Mr. Hall learned that his students actually appreciated the opportunity to start over, and he attempted to honor his philosophy that each day is a new day and opportunity for students in the learning environment. Such an approach—where Mr. Hall refused to hold grudges against his students—was shaped by his emerging and evolving understanding of his students’ identities.

teaching. Through his building of cultural competence, Mr. Hall came to understand that not acknowledging the prevalence and pervasiveness of race could result in incongruence, disconnections, and barriers to success in the classroom. Mr. Hall shared experiences when he was called a racist by some of his students, which really helped shape his thinking and practices related to race:

Just coming from a rural country [town] and coming into the urban areas, the first couple years here, if I got onto some of the ‘‘harder’’ African American kids, you know, who are really into rap…because I don’t listen to

rap…They’d say ‘‘you are racist;’’ they’d walk out the door saying: ‘‘you’re

racist, you’re racist.’’ I’ve got nothing against them, you know, I come here to do one job and that is to teach science…I think some people have it in their

minds that because I am up here, I get on you, I am attacking you personally. That is one of the hardest things to get across to children, is that I am not attacking you; I am attacking your behavior.

Mr. Hall used these experiences when students called him racist as personal and professional opportunities to learn and to build cultural competence. Although it seemed clear that Mr. Hall did not see himself as a racist and that he did not intend for his actions to be interpreted or portrayed as racist, what really mattered was the students’ perceptions; in short, the students’ perceptions actually became their reality. The students, for whatever reasons, classified his actions as racist when he first began his teaching career. Mr. Hall took the perceptions and words to heart— even though he did not necessarily believe he was racist or that he was acting as one. He moved forward but definitely did not take the students’ views and perhaps misconceptions for granted.

In order to move past this incident and to build cultural competence by learning from it, Mr. Hall explained that it was critical for his students to learn more about him and for them to understand some of the commonalities that existed between and among them in order for them to work through the issues that separated them. In other words, he used the conflict and incongruence that seemed prevalent between the students and him as an opportunity to learn and to build cultural competence and to ultimately build connections with his students. He wanted his students to really get to know him so that they would see him for who he really was. In his words,

…I grew up in rural West Tennessee, and I’ve told a couple of kids, I said: I

grew up poor, and we didn’t have anything, you know? I told them I didn’t know what real money looked like until I was about fifteen and had my own job because I didn’t know my family bought food with food stamps…I thought

all money was purple and green and brown. I didn’t know what real money looked like.

race cannot be changed, Mr. Hall seemed to believe that he needed to find other ways to bridge his experiences with his students in order to find commonality and cultural congruence. In his words:

I haven’t brought that [childhood SES] out to everybody but every once in a while you’ll get a couple of attitudes, and you know you just kind of sense that [the students are thinking]–You don’t know where I’m coming from…You

don’t know what it’s like to live here…you know? I told them it’s like living

in the woods is similar to living in a tough neighborhood. The house I grew up in for about 3 years didn’t have indoor plumbing. It was an outhouse. We went outside to go to the bathroom. And a lot of them find that kind of amazing…because even they have never not had a toilet (sic).

Thus, Mr. Hall, through building cultural competence, came to understand the importance of recognizing, confronting and addressing student identity, racial tensions, and conflicts in particular that seemed to emerge between students and him. Mr. Hall explained that it was thesituations of strugglethat often helped the students in his classes connect with him and realize that he was not a racist. He stated:

The struggle of being a human being is that everyday is not going to be sunshine and roses–that’s what I told them…I said everyday is not sunshine

and roses; some days it clouds up; some days it rains; but hey there’s always tomorrow. So don’t worry about it.

The fact that Mr. Hall acknowledged and engaged the importance of identity and race with his students served as a bridge in terms of building relationships with them. Mr. Hall likened his students’ socio-economic status with his own as a child growing up living in poverty. He explained that because many of the students experienced financial turmoil and were growing up in ‘‘tough’’ neighborhoods, they looked at him as somewhat of an outsiderbeforelearning more about his life experiences, past and present. Mr. Hall’s approach to include personal stories about growing up living in poverty served as an important opportunity for the students to decipher some connections but also for Mr. Hall to reflect about who he was in relation to his students. In this sense, not only were the students building knowledge about Mr. Hall, Mr. Hall was building cultural knowledge about himself. Students saw him, in the beginning, as a ‘‘White’’ teacher who perhaps did not have very much in common with them. Some consistently reminded Mr. Hall that they ‘‘did not know’’ him. He explained that he had to share with some of his students that, indeed, he understood struggle and that there were more commonalities between them than what the students probably could imagine from the surface—just by using race as a tool of phenotype. Since his experiences where he was called a racist earlier in his career, Mr. Hall perceived his teaching as a collective, communal commitment, and he used a family frame of reference as an opportunity to continue building cultural competence.

Communal Commitment: A Culture of Care and Collaboration

from each other, and teachers from each other, Dillard (2002) stressed the necessity of people in education to connect to common experiences that unite all in the classroom and school. Mr. Hall stressed that teachers often have to assume different roles for their students in the learning environment, not just in a particular classroom:

For some kids you are going to be mama, daddy, brother, auntie, uncle, grandmother, and granddaddy. I mean you’re going to be the one person who they’re going to tell everything to. [For] some of them, it’s going to be almost like a big brother. They’re going to do what you do. Now if you’re modeling good behavior, they’re going to act like you, almost like a younger sibling would.

Mr. Hall asserted that teachers have to model ‘appropriate’ behavior at all times because students are often watching them, and the students see (some) teachers as role models. There are multiple communal and family roles that successful teachers must play in the urban and diverse classroom:

Some of them you have to be the father figure to. You have to be stern, and let them know that ‘hey we don’t do this–it’s not right.’ Other ones you might just have to be almost like a mom to them; you have to coddle them a little bit…’You know–it’s okay, you can do it…keep trying’…6

Mr. Hall embraced the idea that his students were like his family. He explained that family members care about each other and are not willing to let each other fail. Again, Mr. Hall developed this mindset in order to connect with his students and ultimately for curricular congruence, pedagogical congruence, and cultural congruence. Moreover, he embraced such an approach because it allowed him to build cultural knowledge and competence. Perhaps Mr. Hall’s decision to grant students’ multiple opportunity to turn in assignments or to ‘‘correct’’ their behavior was a consequence of his view that his students were like his family members. The ‘‘family’’ affair approach allowed him to recognize the positive attributes of his students. He was able to see the ‘‘good’’ in his students, even those who others had given up on and even those who sometimes caused problems in his classes. Family members do whatever is necessary—in Mr. Hall’s words: ‘‘whatever it takes’’ for their family to succeed. Family members rarely let other family members fail:

I like the family aspect because I mean if family’s not important to you, then what [or who] is? I mean family should be the thing that’s most important to everybody. And I mean that for some people it’s not, so hopefully in here they kind of get that aspect…I care about everybody; I love them all…just like I

would my own [biological children]…If I holler at you it’s because I know

you can do better. And if I get onto you, I know that you’re slacking; you’re not pulling your weight.

6 It is important to note that it appears that Mr. Hall is ascribing stereotypical gender roles here that some

Mr. Hall explained that family and community are established not only with the students in a teacher’s classroom at present. Rather, he was able to develop and sustain strong family-like and community relationships in the larger school community in other ways as well. Some of his decisions, experiences, and practices allowed students in the greater Bridge Middle School community to get to know him and for him to get to know other teachers and students in the social context:

…Another thing [I] started doing last year is we had a couple of new teachers

who were on the first floor. And during my planning time I’d just walk in and check on them. So kids who I didn’t even have, they were seeing me. And if they were acting crazy, I was taking them, and we were coming up here, and we were doing sixth grade science in my room. And I think just to gain that reputation now, you know, you might not teach them that year–but you’re always watching them. And if you’re around they’d better be acting right. So the school is the community.

Thus, Mr. Hall developed a relationship and reputation with his colleagues and with students who were not even in his classroom. He also was establishing meaningful relationships with new teachers in the school and setting the tone for the kind of teacher he would be when students enrolled in his class in the future. The idea was ‘‘we are family and a community, and we must work together.’’ Clearly, Mr. Hall believed that ‘‘If you quit caring about what you’re doing, that’s when you stop improving. You [can’t] quit caring about the kids.’’ Mr. Hall took his teaching responsibility quite seriously. He believed that when he was teaching he was ‘‘fighting’’ for the lives of his students in the entire Bridge Middle School community:

You’ve got to fight against everything else in their life for their attention for that 1 h. And if you can win the battle you’ve won the child for that 1 h, and 99% of the time they are going to remember the important things you talked about.

Mr. Hall’s point here is tantamount to Ladson-Billings’ (2000) idea that teachers (and other adults in general) are actually fighting for the lives of students. Mr. Hall had a mission to teach his students because he realized the possible risks and consequences in store for the students if he did not teach them well and if the students did not learn. An undereducated and under-prepared student from an urban and diverse school (and possibly any school) could possibly fall into destruction and obliteration (drug abuse, prison, violence, gangs or—even worse—death). Mr. Hall seemed to understand the serious consequences that could manifest, and he was able to gauge these consequences due to his building of cultural competence at Bridge Middle School.

Implications and Conclusions

cultural competence in his urban and diverse classroom through the building and sustaining of meaningful and authentic relationships with his students. The relationships Mr. Hall was able to build with his students were essential to what students shared with him. It was through Mr. Hall’s listening that he was able to build cultural competence—not only about his students but also about himself—to respond to the curricula and pedagogical needs of all his students.

Another experience that assisted Mr. Hall in building cultural competence was hisdecision to recognize his own and his students’ multiple and varied identities. Moreover, as he learned from his students, it was necessary for Mr. Hall to confront matters of race. In fact, some students insisted that Mr. Hall confront race in particular because they actually called him a racist when he first started teaching. He was able to build an understanding of how he was perceived by his students, and he worked to change this negative view. In essence, he understood that the students’ perceptions were actually their realities, and he refused to adopt a color-blind approach to his practices with students (also, see Milner2008).

In addition to building solid relationships, to recognizing student identity, and to confronting the salience and persistence of race, Mr. Hall perceived teaching as a family/communal affair. Accordingly, he was able to learn from students both inside his classroom but also from students and colleagues in other areas of his school. Mr. Hall worked to create a culture of collaboration with colleagues and considered all students in the context his responsibility—not only those enrolled in his classes. He would check in on new colleagues and correct the off-task behaviors of students in the learning context. Thus, Mr. Hall was not only learning from students in his classroom, he was also learning from those outside of his classroom which helped him build cultural competence with the goal being to develop optimal learning opportunities forallstudents.

In summary and conclusion, the ability of Mr. Hall to develop culturally relevant pedagogy in his science classroom seemed to be intimately tied to his ability to build cultural competence. While I agree with the importance of students’ building of cultural competence which shapes Ladson-Billings (1994,2006) conception of culturally relevant pedagogy, where they develop knowledge about themselves and the broader community, I also believe that teachers must constantly build cultural competence. Few would debate the importance of White teachers developing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to teach in urban and highly diverse schools. All teachers, I believe, need to be prepared to teach all students well. And I argue that teachers need to be prepared to do more than teach subject matter such as science, Language Arts, social studies, and mathematics (although I believe teachers need to be well prepared to teach these subjects). However, this teacher seemed to believe that his responsibility did not stop there. As evident in this study,Mr. Hall needed to be prepared to do much more before he could actually even teach science.

that this White teacher was able to develop congruence with his highly diverse learners because he developed cultural competence about them and concurrently deepened his knowledge and understanding of himself.

Teachers can play a critical role in how students engage, conduct themselves, learn, and achieve in urban classrooms. In her ethnographic study of 31 culturally diverse students identified by the school as potential dropouts, Schlosser (1992) discovered how important it was for teachers to avoid distancing themselves from their students by developing knowledge about the students’ home lives and cultural backgrounds and by developing knowledge about the students’ developmental needs. In her words, ‘‘…the behaviors of marginal students are purposive

acts…their behaviors are constructed on the basis of their interpretation of school

life…relationships with teachers are a key factor’’ (p. 137). Not giving up on

students, regardless of their situations, is very important. Students recognize when there is unnecessary distance between themselves and their teachers, and the students’ actions are shaped by such disconnections. Students may question: ‘‘Why should I care about this teacher and what the teacher is requiring of me when the teacher does not really care about me?’’ In this respect, students perceive their poor decision-making, (mis)behavior, and (dis)engagement as ways to distance them-selves from uncaring teachers. Mr. Hall seemed to understand this and worked hard not to distance himself from his students so that students would not distance themselves from him as their teacher and ultimately learning opportunities in the classroom.

Finally, there are positive sides to teachers, students, and urban education, and it is critical for prospective and practicing teachers to be exposed toperspectives and insights of possibilityrather than those that solely or mostly focus and rely on the negative attributes, characteristics, situations, and experiences of teachers, students, parents (and others) in urban schools (Milner2006). As Sleeter (2001) reminded us, researchers should consider focusing their study of P-12 schools in ways that provide conceptual and practical understandings that can be implemented in teacher education—with teachers who will eventually teach in P-12 contexts. Thus, because so much of what teachers have been exposed to in the media, and from their parents or families, for instance, present urban teachers, students, parents, and principals as remedial or unreachable, it is necessary for teachers to experience learning opportunities in teacher education that consider the strengths of those in urban schools. Indeed, this study suggests that, while imperfect, there is hope and possibility at Bridge Middle School.

References

Delpit, L. (1995).Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York: New Press. Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994).Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Dillard, C. B. (2002). Walking ourselves back home: The education of teachers with/in the world.Journal

of Teacher Education, 53(5), 383–392.

Howard, T. C. (2001). Telling their side of the story: African American students’ perceptions of culturally relevant teaching.The Urban Review, 33(2), 131–149.

Irvine, J. J. (2003).Educating teachers for diversity: Seeing with a cultural eye. New York: Teachers College Press.

Kerl, S. B. (2002). Using narrative approaches to teach multicultural counseling.Journal of Multicultural Counseling Development, 30(2), 135–143.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1992). Liberatory consequences of literacy: A case of culturally relevant instruction for African American students.Journal of Negro Education, 61(3), 378–391.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994).The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African-American children. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2000). Fighting for our lives: Preparing teachers to teach African American students. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 206–214.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). Yes, but how do we do it? Practicing culturally relevant pedagogy. In J. Landsman & C. W. Lewis (Eds.),White teachers/diverse classrooms: A guide to building inclusive schools, promoting high expectations and eliminating racism(pp. 29–42). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishers.

McCutcheon, G. (2002).Developing the curriculum: Solo and group deliberation. Troy, NY: Educators’ Press International.

Milner, H. R. (2006). Preservice teachers’ learning about cultural and racial diversity: Implications for urban education.Urban Education, 41(4), 343–375.

Milner, H. R. (2007). Race, culture, and researcher positionality: Working through dangers seen, unseen, and unforeseen.Educational Researcher, 36(7), 388–400.

Milner, H. R. (2008). Disrupting deficit notions of difference: Counter-narratives of teachers and community in urban education.Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(6), 1573–1598.

Monroe, C. R., & Obidah, J. E. (2004). The influence of cultural synchronization on a teachers perceptions of disruption: A case study of an African-American middle-school classroom.Journal of Teacher Education, 55(3), 256–268.

Rios, F. (Ed.). (1996).Teacher thinking in cultural contexts. Albany: State University of New York Press. Schlosser, L. K. (1992). Teacher distance and student disengagement: School lives on the margin.Journal

of Teacher Education, 43(2), 128–140.

Seidman, I. (1998).Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. New York: Teachers College Press.

Sleeter, C. E. (2001). Epistemological diversity in research on preservice teacher preparation for historically underserved children.Review of Research in Education, 25, 209–250.