‘FDI

and

Poverty’

Evidence from KwaZulu Natal – SA

A

Dissertation

submitted

in

partial

fulfilment

of

the

requirements

for

the

award

of

MSc

in

International

Development

Submitted

on:

29

th

September,

2011

Word

Count:

12,

289

Kenneth

Okwaroh

Ochieng’

ID

No.

1078103

Supervised

by

Dr

Philip

Amis

International

Development

Department

Dedicated to the two most special women in my life

Ms Nancy Aruwa and Mrs Monica Ochieng’

True, a good woman can sure inspire a man to be a

better and greater person

Acknowledgements

This piece of research is the product of hard work, patience and diligence of a host of individuals in the

UK and the RSA. I thank Dr Gill Bentley of the Centre for Urban and Regional Studies ‐ University of

Birmingham, Professor Khadiagala of the University of the Witwatersrand, Dr Fiona Nunan and Gareth

Wall of IDD, University of Birmingham for blessing me with the confidence to research on this subject. I

also extend my gratitude to Anne and Debra and the IDD fraternity for the encouragement and goodwill

and most sincerely appreciate the patience, insight and friendliness of my supervisor Dr Philip Amis

throughout the process of researching and writing this dissertation.

I say thank you to my esteemed friend Jerry Asaka, for squeezing in time to read through my drafts with

‘toothpick precision’ and to comrades Cosmas Butunyi and Hezron Ogutu for hosting me in Jo’ Burg and

making the field work fun; the many late nights and informal chats at Stones, Dros, the PiG sure added

value to this piece. Very grateful to the eNseleni community, especially Zakhele Zulu for translating and

supporting me during the FGDs when my isiZulu couldn’t suffice and to E.Mthinyane for rescuing me on

the night I arrived in Richards Bay with no clue where to go. Special gratitude to the DTI, the Department

of Labour, The IDC and the MNCs in Richards Bay for the crucial information without which this research

would not have materialized.

I am forever indebted to the Allan and Nesta Fergusson Charitable Trust for the scholarship, Dr Joshua

Odongo Oron of Widows and Orphans International, London for funding my maintenance, Dr Adrian

Campbell for promptly responding to my distress call and to Mohamed Khalif for being my brother away

from home.

Lastly, William Shakespeare said that ‘love is a spirit of fire, not gross to sink but light and will aspire’. I am humbled

by the grace of the almighty God for blessing me with an awesome family. Addy, Adiki, Hilary, Beryl, Tony,

Marion, Nancy, Mom and Dad, you guys kept me alive. The prayers, the phone calls and most importantly

the LOVE; thank you so much.

Okwaroh Kenneth Ochieng’, Birmingham – UK

okwaroh@gmail.com

Abstract

Contents

Dedication ‐ii‐

Acknowledgements ‐iii‐

Abstract ‐iv‐

Contents ‐v‐

List of Acronyms ‐vi‐

Chapter One – Introduction 1

Chapter Two – A Review of Literature 4

Chapter Three – Analytical Framework 13

Chapter Four – Methodology 17

Chapter Five – Context 21

Chapter Six – Findings and Analysis 25

Chapter Seven – Conclusion 40

References 43

Appendix I – Summary of Relevant Studies Reviewed

Appendix II – Discussion Guide

Appendix III – Data Analysis

Appendix IV – Maps

List

of

Acronyms

AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome BPM5 Balance of Payment Manual – 5th Edition CIA Central Intelligence Agency

DBSA Development bank of Southern Africa DTI Department of Trade and Industry EPZ Export Processing Zone

FDI Foreign Direct Investment FGD Focus Group Discussions GDP Gross Domestic Product

GEAR Growth Employment and Redistribution Strategy GNI Gross National Product

HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus IDZ Industrial Development Zone IPAP Industrial Policy Action Plan MNC Multinational Corporation

MTSF Medium Term Strategic Framework

NALEDI National Labour and Economic Development Institute

OECD Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development PRSP Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

RIDP Regional Industrial Development Programme RSA Republic of South Africa

SADC Southern Africa Development Corporation SDI Spatial Development Initiative

SMME Small Medium and Micro Enterprise

UNCTAD United Nations Conference on Trade and Development UNECA United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Organization

Chapter

1

‐

Introduction

1.1. Background

Inward Foreign Direct Investment continues to be seen as an important driver of economic development, a precursor for employment creation and as a tool for eliminating poverty and addressing spatial economic imbalances (Hill and Roberts, 1998; Aaron, 1999; Jenkins and Thomas, 2002; Mwilima, 2003; Tambunan, 2005; Jenkins, 2006). The business of inward investment attraction has become an integral part of economic policy and a standard operation of state departments especially in developing economies today. In academia as well, the subject of inward investment has received considerable attention, been well researched and substantively written on. However, the link between FDI and poverty reduction remains insufficiently investigated; there is inadequate and inconclusive evidence on the impact of FDI in improving the livelihoods of the poor (Sumner, 2005). Aaron (1999) argued that there is no direct link between FDI and poverty reduction. That what exists is a two tier relationship i) between FDI and economic growth and ii) between economic growth and poverty reduction. This argument is reinforced by Te Velde (2002) who asserts that in principle a direct link between poverty reduction and FDI does not exist though the possibility of indirect links is defensible. The overall assumption has been that it is possible to enhance location competitiveness, intensify place marketing, attract inward investment, and then let the benefits of investments ‘trickle down’ to the poor (Davila, 1996; Gilbert, 1997; Potter and Moore, 2000). That attracting inward FDI increases the opportunities for the creation of employment which the poor can take up in order to increase their incomes and to improve their overall wellbeing.

others as well that determine the capacity of the poor to take advantage of such employment opportunities to improve their socio‐economic standing. Experience with place marketing and inward investment attraction has indicated that the trickle down is problematic and there is no guarantee that the benefits of such investments reach the poorest, most deprived and socially excluded segments of the population (Turok and Bailey, 2004; Tallon, 2010). There is evidence of increasing polarisation, unemployment and exacerbated poverty in many urban areas against a background of active place marketing, increased investment and economic growth (Boddy, 2002).

1.2. Significance of the Study

This piece of research sought to contribute to the debate on the link between FDI and poverty reduction. It set out to interrogate the argument that FDI can be relied on to reduce poverty especially in developing economies. It involved an analysis of perspectives of MNCs, Government Departments and the local population on inward investment and employment creation and how this affected the poverty situation in eNseleni ‐ Richards Bay; an urban setting in post‐apartheid South Africa where close to two decades of government policy on industrial decentralisation, place marketing and investment promotion was considered to have succeeded (Aniruth and Barnes, 1998; Jourdan, 1998; Rogerson, 2001); yet the poverty situation had not significantly improved (May et al, 2006; Department of City Development, 2009).

1.3. Structure of the Paper

The paper is divided into seven chapters namely; the Introduction, Literature Review, Analytical Framework, Methodology, Context, Findings and Analysis and lastly Conclusion. Chapter Two

The content of Chapter Three largely draws from the survey of literature in the previous chapter. It presents a framework of analysis developed from Tambunan (2005) that depicts the relationship between FDI and poverty reduction bridged by pro‐poor employment creation. Chapter Four

outlines the approach employed in gathering data for the study; the overall research methodology is discussed here in detail.

Chapter Five provides a background profile of the context within which the study was undertaken; a succinct account of the poverty situation in South Africa and some recent socio‐economic developments of relevance to the study. Chapter Six is a presentation of the findings from the field. It involves a detailed analysis of the key themes drawn from the analytical framework: a summary of overarching perceptions of respondents is used to stimulate a discussion on the capacity of FDI to contribute to the reduction of poverty. Chapter Seven outlines the conclusions drawn from the analysis and the key recommendations for further research as well as policy suggestions for future government action on poverty reduction buttressed on FDI in South Africa and other developing economies.

Chapter

2

‐

A

Review

of

Literature

2.1 Introduction

This chapter examines literature on the role of inward investment in generating employment that is accessible to the poor in their host economies. It begins with an overview of Foreign Direct Investment, and then proceeds into a succinct exposition of the incoherent link between inward FDI and the reduction of poverty. What follows is a discussion on how FDI could lead to employment creation and what might prevent this. It ends with a reflection on the critical issues of concern that guide the analysis of the case study and some concluding thoughts on the literature.

2.2 Inward Foreign Direct Investment – An Overview

The fifth edition of the Balance of Payment Manual defines FDI, also referred to in this paper as inward investment, as investment made to acquire a lasting interest in an enterprise operating outside of the country of the investor. Hill and Roberts (1998) defined FDI as ‘the ownership and control of productive assets in [a host economy] by foreign persons’ (Hill and Roberts, 1998:31). The OECD Benchmark definition of FDI states that it involves ‘obtaining a lasting interest by a resident entity in one economy in an entity resident in an economy other than that of the investor’ (OECD, 1996:7). Essentially FDI reflects the injection of money from sources outside a country for the purposes of establishing or purchasing capital goods necessary for locating or developing a lasting business presence in the country in question. What the lasting interest implies is that the external entity reserves a substantial degree of control and influence in the management of the establishment, normally in the form of equity ownership or voting power of not less than 10% (UNCTAD, 2006). Though FDI can be either inward or outward, it is inward investment that is of profound importance to this study.

2.3Inward FDI and poverty reduction – ‘an incoherent link’

Many developing economies see inward investment as an important driver of economic development, a precursor for employment creation and as a tool for reducing poverty and addressing spatial economic imbalances (Hill and Roberts, 1998; Aaron, 1999; Ngowi, 2001; Jenkins and Thomas, 2002; Mwilima, 2003; Tambunan, 2005; Jenkins, 2006). However, the link between inward investment and poverty reduction remains unclear and insufficiently investigated. There is inadequate and inconclusive evidence on the impacts of FDI on the improvement of the livelihoods of the poor (Sumner, 2005). Nonetheless most of the scholars1 who have attempted to trace the link concur that the degree to which inward investment generates employment opportunities accessible to the poor and the ability of the poor to take advantage of such opportunities so far represents the most tenable linkage.

FDI proffers a range of benefits that include (but not limited to) the attraction of private capital, creation of competitive business environments, growth of domestic enterprise through linkages and spill‐overs as well as human capital development through employee training and capacity building that all have crucial bearing on the improvement of job opportunities in a host economy (Blomström, 2002; Stimon, Roberts and Stow, 2002). Tambunan (2005) studied the impact of FDI on poverty reduction in Indonesia; he argues that providing the poor with productive employment underpins the relevance of FDI in developing countries where unemployment is perceived to be a product of dismal domestic and foreign investment. Aaron (1999) notes that FDI could stimulate the expansion of employment, improve human capital and enhance transfer of technology and diffusion of skills from developed nations to developing economies. He however cautions that the capacity of FDI to deliver such benefits is subject to context specific investment environments prevalent in different economies.

1 See annex 1 for a comprehensive summary of studies on the link between FDI and poverty reduction that were reviewed by the

In his study on FDI and employment in Vietnam, Jenkins (2006) argues that FDI that supplements domestic investment; creates new labour‐intensive industries; stimulates backward or forward linkages and generates spill‐overs to domestic firms has better prospects for employment creation. He however notes that it is possible for FDI to have marginal (may be even negative) consequences on employment if it severely crowds out domestic enterprise to the extent that the volume of jobs lost far outstrips that created by the MNCs (Jenkins, 2006:116). Jenkins and Thomas (2002) investigated the trends of FDI and its implications for economic growth and poverty alleviation in Southern African countries. They argue that though it does create new jobs and facilitate technology transfer and diffusion of skills, without effective mechanisms for equitable distribution of benefits, a positive impact on poverty alleviation and improvement of social welfare is not guaranteed (Jenkins and Thomas, 2002). Te Velde and Morrissey (2002) note that FDI may increase labour productivity through technology or skills transfer, but its impact on poverty reduction might be constrained by inequitable distribution of such benefits amongst sectors, regions or cadres of workers. Using evidence from studies in Africa and East Asia2, they demonstrate how FDI often raises income inequalities leaving less skilled workers more disadvantaged as their skilled counterparts continue to attract higher wages.

2.4 How inward FDI may or may not create employment for poverty reduction

Academic literature has approached the link between FDI and employment creation in three main ways. Through labour intensive investment; through backward and forward linkages between MNCs and domestic firms that stimulate growth of domestic SMMEs; and through spill‐overs from MNCs that improve human capital and enhance productivity and ability of domestic enterprises to absorb more labour.

2

2.4.1 Backward or Forward Linkages and employment creation

Backward or forward linkages are the complementary business contacts and relationships between MNCs and local enterprises (Jenkins, 2006). They emerge when the presence of MNCs stimulate the growth of local firms or sectors that supply them; when MNCs generate demand for inputs that induce the establishment of domestic enterprise for instance through subcontracting arrangements for supply of inputs that are more economical to produce locally (Hirshman, 1958). Linkages may also emerge when MNCs produce intermediate goods that induce local firms to process further – these are known as forward linkages (Jenkins, 2006).

Proponents of this approach argue that inward investment linkages create business opportunities for local enterprise; they open up new markets for SMMEs, offer stable and regular payment for the supply of inputs and help local firms achieve economies of scale by increasing demand for locally produced intermediate goods. The logic is that by inducing additional domestic investment and increasing productivity of local firms, such linkages bolster the ability of local enterprises to absorb more labour thereby expanding job opportunities for poor locals (Hirshman, 1958; Dunning, 1992; Jenkins, 2006). O’Hern (1989) argues that since there must exist adequate investment outlets for FDI to succeed even marginally in creating pro‐poor jobs, such linkages are a possible way through which such outlets could be established. In 1999 alone, backward production linkages between foreign companies and local firms were responsible for the employment of over 13 million people worldwide (Aaron, 1999). This implies that besides directly employing locals, MNCs can indirectly create jobs in a local economy where they exist through supplier arrangements and subcontracting relationships.

volume of business and a considerable degree of stability in order to guarantee productivity of domestic enterprise and security of jobs created. However, empirical evidence to show that the existence of foreign firms creates or increases such linkages in developing countries is inconclusive. Javourcik (2003) argues that data limitations prevent researchers from providing conclusive evidence on the conduct of the externalities created by FDI. Calagni (2003) nonetheless, noted that FDI skewed in natural resource extraction sectors3 limits linkages with local enterprise and constrains job creation in Sub‐Saharan economies. And that overly liberalised FDI policies that allow MNC to import most of their inputs also fundamentally eliminate possibilities of linkages and profoundly limit job creation.

2.4.2 Spill‐overs and employment creation

FDI might also generate employment accessible to the poor through the diffusion of skills and transfer of new technologies, knowledge and innovations from foreign enterprises into a domestic economy (Tambunan, 2005). This is what is referred to in the literature as the spill‐over effects ‐ normally actualised through imitation of production systems introduced by foreign investors, through demonstration of exotic technologies to domestic enterprises or through competition induced by MNCs (Mac Dougall, 1960; Blomstrom, 1989). Foreign companies educe spill‐overs through their demand for technical or managerial skills which necessitates the training and interaction of local employees with foreign personnel to adapt to the exotic production systems (Jenkins and Thomas, 2002). This way, they transfer new knowledge, technologies and other intangible assets that enhance efficiency and productivity of domestic enterprise and employability of local workforce (Graham and Krugman, 1995). Such technological capabilities, entrepreneurial and managerial skills accrued from MNCs have the potential of generating new SMMEs that create additional jobs especially where trained personnel leave MNCs to establish new businesses or work for local firms (Smallbone, 2006).

However, the capacity of FDI to generate such spill‐overs and the possibility of the poor benefitting from them has been questioned. Rodrick (1999) noted that policy literature on investment attraction is laden with claims about possibilities of industrial externalities and spill‐overs without adequate evidence to back it. A host of studies4 examining the productivity of firms correlated with the presence of MNCs cast doubts on the existence of FDI induced spill‐overs in developing countries. Haddad and Harrisson (1993) investigated the effect of inward investment in Morocco. They reject the assumption that the presence of large MNCs in a host economy automatically accelerates growth in domestic enterprise and stimulates spill‐overs. Javoucick (2003) analysed firm‐level panel data sets on FDI spill‐overs in Lithuania and concluded that there was limited evidence of such spill‐ overs. Calagni (2003) notes that the mere influx of FDI does not guarantee spill‐overs; they are subject to prevailing domestic investment environments and the capacity of local enterprise to seize market opportunities. Even where spill‐overs have occurred, like in Penang‐Malaysia, Singapore or Bangalore‐India, there was limited evidence to show that employment generated was accessible by poor. They loosely affected the skills and capacities of lower echelons of the workforce and completely marginalised those not employed at all. Lyanda and Bello (1979) also studied fourteen MNCs in Lagos, Nigeria and established that their training programmes targeted highly qualified white collar than blue collar (less skilled) workers.

2.4.3 Labour intensive investment and employment creation

Most developing countries are labour rich, but capital poor (Jenkins and Thomas, 2002; UNECA, 1995). This is attributable to low per capita income that limits domestic saving capacity, poor financial intermediation and low export GDP ratios that translates into insufficient resources for domestic investment (UNECA, 1995; Tambunan, 2005). Inward investment therefore functions to

4 Studies carried out at industry level, based on firm level panel data or case study oriented like Santiago (1987) in Puerto Rico, Aitken and Harrison (1999) in Venezuela and Djankov and Hoekman (2000) in the Czech Republic. Also see Appendix 1 for a

bridge the gap between available domestic savings and the volume of investments that a country requires in order to achieve economic growth (Smallbone, 2006; Jenkins and Thomas, 2002). Aaron (1999) argues that inward investment that enhances capital formation and creates demand for more labour as well is strategic for job creation and distribution of economic growth benefits to the poor.

UNIDO (2006) recommended that low income countries should focus on labour intensive investments since they involve greater engagement of people and utilisation of cheap labour if they aim to succeed in ameliorating poverty. There are three main arguments for this approach. The first one is that the main tasks in labour intensive enterprises (like apparels, textiles and garments or footwear) do not require high qualifications, skills or experience and thus can easily be performed by the poor (UNIDO, 2006). Secondly, that labour intensive investments offer substantially higher wages than earnings from rural peasant production but low enough to maintain their competitive edge (UNIDO, 2006). The third argument is linked to the capacity of labour intensive investments to absorb more labour than capital intensive ones. The export oriented labour intensive garment industries in Kenya and Bangladesh for instance absorb more labour with wages significantly higher than the countries’ poverty lines5. Lall (1995) argues that though labour intensive MNCs characteristically have limited capacity to generate deep linkages and spill‐overs, they create substantial additional employment and encourage entrepreneurship and "export culture" (Lall, 1995:9).

However, not all labour intensive investments create pro‐poor employment. Those centred in non‐ poor sectors (non‐agricultural, non‐manufacturing) that employ skilled, non‐poor urban labour are likely to have marginal impact and may further income inequality (UNIDO, 2009). Labour intensive FDI must have low entry barriers (in terms of skills, training or experience) and allow for flexible work patterns in order to accommodate the poor (Aaron, 1999).

2.5 Human Capital ‐ A key determinant of the impact of FDI on job creation

Human capital has a strong influence on the embededness6 of foreign investments and the transfer of

their benefits to a local economy (Morgan, 1998; te Velde, 2001; Blonigen and Wang, 2004). Borensztein,

De Gregorio and Lee (1998) found that human capital profoundly determines the impact of FDI on per

capita income in many developing countries; that a particular threshold of growth in skills or education

levels must be attained for MNCs to confer tangible benefits to a local population. Te Velde (2001) adds

that a well‐educated, trained or trainable workforce is crucial for attracting MNCs and encourages a wide

spectrum of spill‐over effects with domestic enterprises (Moran, 2005). Morgan (1998) argues that the

impact of FDI on employment creation is subject to the quality of human capital in the host economy;

skills and training determine the adaptation to new technologies and rate of new innovations. And

according to Javourcik and Spatareanu (2004) human capital has significant bearing on the ability of

domestic enterprises to qualify for production subcontracting or supplier relationships with MNCs which

are the major avenues through which FDI could generate employment.

Jenkins (2006) however, cautions that where FDI is dominated by MNCs that demand highly specialised

skills, the net effect on employment accessible to the poor is conversely marginal and might create short

term job attrition. Bhorat and Poswell’s (2003) study of the impact of FDI on the South African labour

market established that technological change reinforces demand for skilled or highly qualified labour

which fundamentally furthers the skewing of employment and income distribution against poor

workforce normally with limited educational qualifications or skills.

Te Velde and Morrissey (2001) therefore argued that a host economy’s investment policy must aim to

enhance human capital; support the provision of specialised training, skills upgrading or basic education

for low or unskilled workers not only to attract MNCs but also to improve their bargaining power and

6 Embededness refers to the “… the depth of and quality of the relationships between inward investors and local firms and organizations, and the extent to which spillovers provide opportunities for local economic development” (Phelps et al, 2003). Also see Dicken et al (1994) and White (2004) for a more detailed discourse on the concept of ‘embededness’

access to employment. This is because foreign investors certainly are business people looking to make

profits hence would not have sufficient capacity and be adequately incentivised to train low skilled

workers (Aaron, 1999; Te Velde and Morrissey, 2002).

2.6 Conclusion

The linkage between FDI and poverty reduction has been explored extensively in this chapter. Multiple avenues through which inward investment could generate employment accessible to the poor in developing economies have been considered. Whilst the evidence is not sufficiently conclusive on the link between inward investment and employment creation and further on poverty reduction, a few critical issues emerge from the literature that could perhaps form the foundation

upon which the case study is analysed:

1. The influence of the mode of production (in terms of labour or capital intensiveness) on the capacity of foreign firms to generate employment that the poor can take up.

2. The idea of linkages between MNCs and domestic enterprises and the scope of employment such business relations can generate.

3. Technological and skills transfers, how they influence the productivity of domestic enterprises, and the benefits the poor can draw from them.

4. The influence of human capital on the link between FDI and poverty reduction. How

skills and work experience affects the creation of jobs and the ability of the poor to

profit from such employment.

Chapter

3

‐

Analytical

Framework

Drawing from the critical issues outlined in the conclusion of the literature review, a framework developed from Tambunan (2005) study of the impact of FDI on poverty reduction in Indonesia was adopted to analyse the case study and interrogate the critical issues that emerge in order to provide answers to two main research questions:

1. How has the nature of investments in Richards Bay influenced the creation of employment accessible to the poor in eNseleni?

a. Are the MNCs labour or capital intensive?

b. Do the foreign firms do business with local enterprises?

c. Have the MNCs transferred new skills, technologies or innovations to local enterprises and people in eNseleni?

2. Of what influence is human capital on the ability of the poor in eNseleni to benefit from employment generated by MNCs in Richards Bay?

a. What skills do the MNCs prefer?

b. Does the local population have the skills preferred by the MNCs?

c. Are there any skills development programmes to equip the local population with the qualifications demanded by the MNCs?

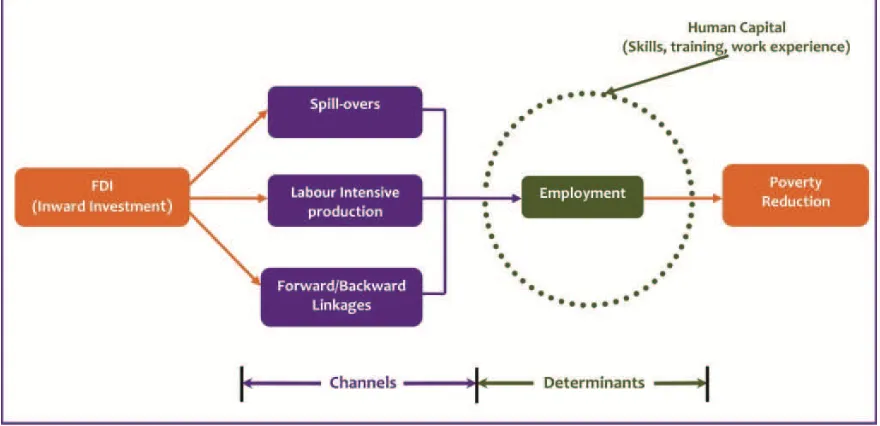

Figure 1.0 below is a schema of the framework showing the possible link between FDI and poverty reduction. What follows is a succinct discussion of the framework, an explanation of the schema and a justification for the employment of the framework in the study.

Figure 1: ‐ Analytical Framework. Developed from Tambunan (2005) pp 5‐18

3.1 The Channels

The framework indicates that there is no direct link between FDI and poverty reduction but an indirect one facilitated by the creation of employment7 ‐ that FDI must create employment accessible to the poor if it is targeted at reducing poverty. It suggests three possible ways MNCs could increase job opportunities for poor people living in the areas they locate. It shows that:

1. FDI can generate spill‐overs ‐ the diffusion of knowledge and innovations, skills

and new technology into a host economy. Conceptually, such spill‐overs can

stimulate growth of new enterprise, improve productivity of domestic firms,

create additional jobs and augment individual incomes in a local economy.

2. MNCs may induce backward or forward linkages that might expand business

opportunities for local firms and also stimulate the emergence of SMMEs to

engage in subcontracting arrangements or supply inputs considered cheaper to

produce locally. The net effect of this is a possible augmentation of demand for

labour with profound implications on the creation of jobs that poor people can

take up in order to increase their incomes and improve their livelihoods.

7 Though Tambunan (2005) also discusses the possibility of host governments committing tax revenue accrued from FDI to

[image:21.595.78.518.53.266.2]3. Foreign companies can directly employ poor unskilled/semi‐skilled workers

through labour intensive production. When foreign companies demand more

physical labour than capital equipment or machinery, they create more jobs

most suitable and accessible to the poor since a lot of labour intensive

investments involve modest entry levels (in terms of skills, experience or

training) that accommodate the specific characteristics of the poor’s labour.

3.2Determinants of the impact

The framework shows that it is however imperative to underline the importance of human capital in appreciating the link between FDI and poverty reduction. MNCs may indeed be labour intensive, generate spill‐overs and sustain sufficient linkages with local enterprises, yet still fail to appeal to the interests of the poor. The quality of their labour – skills, training or work experience is crucial for: i) acquiring and adopting skills and technologies imported by foreign firms, ii) attaining the entry requirements for employment in the MNCs and iii) increasing their eligibility to better wages. Moreover, human capital profoundly influences the quality and effectiveness of the linkages. Linkages only thrive where there exist skilled entrepreneurs, who venture into employment generating local enterprises to do business with foreign companies. A marked deficiency of human capital would greatly limit the benefits that the poor accrue from MNCs in their localities; in fact, it might exacerbate their alienation from employment and economic activity hence furthering existing income inequalities.

3.3 Justification

determine the accessibility of such employment to the poor, the framework presented a suitable conceptual basis for investigating the conduct of MNCs in the case study area and for stimulating a discussion on their propensity towards job creation for the poor in eNseleni. It neatly blended with the critical issues of concern that emerged from the literature and the research questions that the study sought to answer. It therefore profoundly informed the choice of methods employed in data collection, guided the analysis of data and informed the structure of the discussion of the findings.

Chapter

4

–

Methodology

4.1 Introduction

As already indicated in chapter three, the analytical framework formed the basis of the design and choice of the methods of data collection and analysis employed in this study. This chapter outlines the research approach pursued and discusses the main methods employed to collect data. The researcher believes that the calibre and amount of information captured by these methods established a sufficient factual basis upon which the research questions could be answered and conclusions drawn from them.

4.2 Research Approach

The study adopted an entirely interpretative approach as this offered the option of collating people’s experiences, thoughts and perspectives. This suited the researcher’s interest in the reality of relying on FDI to confer benefits to the poor from the perspective of the investors (MNCs), beneficiaries (eNseleni residents) and the executors of the approach (government officers).

4.3 Secondary Data

A substantial amount of study data was obtained through systemised secondary sources. This involved a documentary analysis8 of materials on the history of inward investment, industrial and regional development policy and how these affected the conduct of poverty reduction programmes and approaches in South Africa and more specifically, Richards Bay. This was obtained from the

Department of Trade and Industry, Industrial Development Corporation, Department of Labour,

uMhlathuze Municipality, the Development Bank of Southern Africa, NALEDI, and the Richards Bay

Industrial Development Zone. This information was very instrumental and indeed indispensable in the verification of primary data.

4.4 Primary Data

4.4.1 Selection of respondents

A sample was derived based on the researcher’s judgement on the suitability and convenience of the respondents9. The firms involved in the study were selected on condition that they had at least 10% ownership attributable to entities located outside the Republic of South Africa. Government officers involved were recruited depending on their contribution to the country’s industrial development, investment and labour policy. eNseleni respondents must have been resident there since 1994, willing and able to participate in the interviews to be selected.

4.4.2 Semi‐structured interviews

Semi‐structured interviews were extensively utilized in gathering primary data. A discussion guide (see appendix II) comprising a set of questions framed from the key thematic areas in the analytical framework was administered to the three categories of respondents. Though the questions were structured differently, they all probed for perceptions along those themes, allowed for broader discussions and accommodated emerging issues from respondents. This broadened the scope and deepened the depth of information collected within the duration of the study while still maintaining a precise focus on the salient issues that were of interest to the researcher.

Three government officers linked to the DTI and the Department of Labour were interviewed to capture their perceptions on the character of foreign investments in Richards Bay and the conduct of their programmes in ensuring that MNCs conferred substantial benefits to the local economy (in terms of employment generation, linkages with local enterprise and enhancement of technological

transfers and knowledge spill‐overs). Five representatives from four Multinational Corporations located in Richards Bay were interviewed to establish the conduct of their modes of production (whether labour or capital intensive), the extent of their linkages with local enterprises, their capacity to generate spill‐overs and the implication of this on the creation of jobs accessible to the poor. The interviews also probed for employment trends in the firms, the skills their production systems required and how they sourced their workforce. Though not initially in the design of the study a researcher from NALEDI and Professor from the University of Witwatersrand was interviewed as well to augment the data on linkages.

4.4.3 Focus Group Discussions

Three FGDs were employed to gather information that may not have been effectively captured by the secondary sources and the semi‐structured interviews and also to allow for interaction amongst respondents and joint determination of responses to the questions asked during the individual semi‐ structured interviews. Groups comprised 6‐8 employed and jobless individuals of both gender and who were in employment age by 1994 when the post‐apartheid government began aggressive inward investment attraction and liberalised FDI. Participants were carefully guided to explore the issue of access to employment, the impact of skills on their ability to take advantage of job opportunities created by the MNCs around Richards Bay, perceptions on the possible ways the investments could improve their livelihoods, what might have been preventing this and what role government should play.

4.5 Case Study

government incentives targeted at industrial decentralisation, investment attraction and place marketing as a strategy for job creation and poverty reduction had succeeded (Aniruth and Barnes, 1998). This was thus a sufficiently pragmatic but suitable setting considering the scope of the study to ask the critical questions about the suitability and capacity of FDI as a poverty reduction mechanism in a developing economy.

4.6 Limitations of the methodology

The researcher recognises that the use of a case study as part of the methodology traded off the capacity to make generalisations and the arbitrary choice of Richards Bay might raise concerns on the representativeness of study data. Accessing respondents from the MNCs (particularly management) was indeed a challenge. However, the researcher improvised and utilised insiders interviewed in confidence outside the formal confines of the companies. In addition, exploring the link between FDI and poverty reduction is itself a complex venture. Poverty is a complex phenomenon (with contested conceptions) and poverty reduction involves a myriad, often overlapping approaches that take long to produce tangible measurable results. Attributing results or linking them to a specific determinant or channel is normally problematic. This study like many other preceding pieces of research on poverty and poverty reduction is no exception to the difficulty in constructing these links.

4.7 Conclusion

Chapter

5

‐

Context

5.1 South Africa ‐ Some basic facts

The RSA was established in 1961 but gained majority rule in 1994 after decades of oppression and racial segregation under the apartheid regime (CIA Fact Book, 2011). It spans an area of 1,219,090 Km2 with a population of 49.3 million and density of 106.2 miles2 (see appendix IV for map). It is listed as an upper middle income country and amongst the top 50 largest economies in the globe.

5.2 Poverty in South Africa and some recent socio‐economic developments

Poverty remains a significant challenge and an object of policy in South Africa. The legacy of apartheid has ensured that the country continues to struggle with entrenched and chronic poverty despite its economic profile as a middle income economy. In 2006, 17.4% were living on less than a US$1.25 a day and 35.7% living on less than US$2.25 a day (OECD, 2011); 32% were living below the R322 lower bound national poverty line and 53% below the R593 upper bound poverty line (Armstrong, Lekezwa and Siebrits, 2008). There are high income inequalities in the country despite signs of economic growth (GDP growth rate of about 2.8% with a GNI per capita of US$ 5,786) ‐ employment generation continues to lag and the Gini coefficient is still at 0.67 (World Bank, 2011). High unemployment (about 25% overall and 29.3% for urban areas), decline in domestic savings and investment, large fiscal deficits and the burden of HIV/AIDS are the major underlying structural issues facing the country (Word Bank, 2011).

Programme, the Growth Employment and Redistribution Strategy (GEAR) that aimed to attain 6% growth and create 400, 000 jobs by 2000, and the Community Based Public Works Programme that sought to improve labour force skills, enhance service delivery and generate large scale temporary employment in public works projects. Others that carried implicit poverty reduction objectives include the Local Economic Development programme, Spatial Development Initiatives, National Spatial Development Framework and the Manufacturing Development Programme (May, ed, 2000). Of profound relevance to this study are those targeted directly or implicitly at increasing inward investment as a strategy for reducing poverty.

5.3Inward Investment in South Africa

Inward investment in South Africa has grown exponentially since 199410 and evolved to become one of the most important drivers of the economy (UNCTAD, 1999). FDI inflows have grown from $1,248 million in 1995 to $9,632 million in 2008; FDI stocks have expanded as well from $15, 014 million in 1995 to $110, 415 million in 2008 (OECD, 2011). South Africa receives a large proportion of FDI to Africa, it accounted for 48% of the $15 billion invested in mining in Africa in 2004 (Mining Journal, 2005). It dominates the FDI inflows of the SADC region and hosts the largest number of MNCs. Between 1997 and 2001 it accounted for 70% of all SADC FDI inflows and more than 70% of MNCs in the SADC region were in South Africa (Jenkins and Thomas, 2002; Akinboade et al, 2006).

5.4Inward Investment in Richards Bay – A historical perspective

‘[Richards Bay] is considered … one of the few localities where government incentives targeted at industrial decentralisation was reasonably successful’ (Hill and Goodenough, 2005:2; Aniruth and Barnes, 1998). Below are some of the inward investment strategies the government has employed since the 1970s and their impact on employment and poverty reduction:

5.4.1 The Regional Industrial Development Programme (RIDP)

The RIDP aimed to address regional economic disparities through provision of incentives to investors to locate in designated growth points. This induced an influx of mobile capital into such areas; firms capitalised on the incentives, concessions and exploitable labour (Nel, 1999). The designation of Richards Bay as an industrial growth pole in the 1982‐1990 RIDP immensely influenced the establishment of crucial infrastructure and location of new businesses. However, the withdrawal of such state supported industrial programmes in 1994 led to the relocation of firms formerly attracted by the incentives, massive deindustrialization, loss of jobs and a surge in unemployment ensued. This severely impoverished locals in the affected areas. Almost an eighth of manufacturing jobs were lost across the country and employment fell by nearly 50% (Nel, 1999).

5.4.2 The Spatial Development Initiatives

The SDIs were tasked to unlock underutilised economic potential of previously neglected areas, reduce poverty through creation of employment and to enhance competitiveness of the national economy. They prioritised investment attraction to generate long term sustainable jobs for poor locals and growth of SMMEs from such investments to further expand employment opportunities and boost regional development (Rogerson, 2001). The Richards Bay SDI identified potential industrial projects in mining and chemical manufacturing that were packaged and promoted to potential investors aiming to crowd‐in investment in the area, maximize on their linkages and multiplier effects to create jobs and increase government revenues (Rogerson, 2001). However, evaluations on the SDIs indicate that they did not have significant impact on job creation and SMME development.

5.4.3 Industrial Development Zones

The IDZs are specialized industrial areas designed to create a conducive and attractive investment environment for export oriented investors and for employment creation. They involve public sector provision of advanced infrastructure, Research and Development support, export financing and a host of incentives targeted at creating the image of an internationally competitive business location. They were designed to involve ‘manufacturing activities linked to local industry that incorporates substantial local inputs [and] downstream manufacturers’ (Rogerson, 1999:268). They recruit light manufacturing factories, assembly plants and technologically intensive firms that involve high levels of value addition and employ both highly skilled and unskilled labour. They also incorporate natural resource extraction based capital industries. There is an IDZ in Richards Bay that is currently operational.

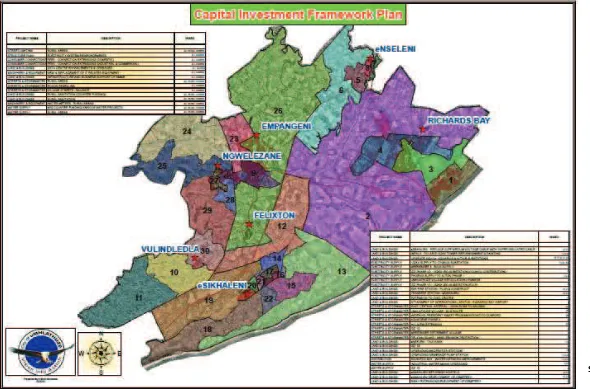

5.5 Putting eNseleni into context

eNseleni is a suburban fringe of Richards Bay town in the KwaZulu Natal Province of South Africa with a population of about 14,682 and a density of 6,421 Km2 (see appendix III for map). Despite the industrial investments around Richards Bay, poverty remains a big challenge in eNseleni with over 23% of households not earning any income at all and over 4,500 economically active individuals earning less than R400 a month against a national poverty line of R593. By 2010 unemployment rate was 55% compared to 36.28% for the municipality and 24.3% nationally (Statistics South Africa, 2011; uMhlathuze Municipality, 2009). Manufacturing is the largest source of employment ‐ accounts for 24% of all employment11. Levels of formal education are fairly low – only 30% have post‐secondary education qualifications; 20% have elementary skills/education, 14% have some craft and trade related capabilities, 9% have some skills in plant operations, 11% have clerical skills. Only 2% of total employable workforce is regarded as skilled (uMhlathuze Municipality, 2009).

11Other sources of employment include community service – 16%; trade – 13%; finance – 10%; construction – 8% and mining – 5%

Chapter

6

‐

Findings

and

Analysis

6.1 Introduction

In the course of the research, relevant secondary literature in the form of study reports, financial

statements, government departmental records and policy documents related to employment creation,

industrial development, and poverty reduction were reviewed. These were sourced from South Africa’s

Department of Trade and Industry, Industrial Development Corporation, Department of Labour,

uMhlathuze Municipality, the Development Bank of Southern Africa, NALEDI, and the Richards Bay

Industrial Development Zone. A three weeks field work was also carried out in eNseleni‐Richards Bay, in

the KwaZulu Natal Province of South Africa that involved 10 semi‐structured interviews and 3 FGDs with

23 local residents of eNseleni. This chapter is a presentation of the data captured and an ordered analysis

oriented towards answering the two research questions.

6.2 What FDI in Richards Bay looks like and what it implies for employment

creation and access in eNseleni

The study assessed the foreign investment situation in Richards Bay; the character of MNCs and how the type of investments (in terms of their ability to absorb labour, their linkages with local enterprises and spill‐over effects) influenced access to employment by the poor resident population in eNseleni. Four major issues became apparent: investments were acutely capital intensive, induced significant but weak linkages with local enterprises, generated limited spill‐over effects and that the population was constrained by skills inadequacies in their pursuit of decent work.

6.2.1 Acutely Capital Intensive investments

Guided by the analytical framework, the question of the mode of production favoured by the MNCs ‐

whether labour or capital intensive ‐ was considered. This aimed to establish the extent to which the

MNCs involved in the study depended on capital equipment or machinery compared to human labour in

order to determine the scope of employment the MNCs could generate that the poor could benefit from.

Nearly all the major industries in Richards Bay were capital intensive. Though this was not surprising,

since two World Bank reports on the investment climate and the character of FDI in South Africa (in 2007

and 2010) had indicated that a lot of investments in the country were capital intensive, the finding that

over 90% were capital intensive was not obvious. Most of the investors in the area were incetivised by

the occurrence of rich mineral deposits and other natural resources like wood/pulp and extensive arable

land. The three main industries were involved in coal mining, beneficiation of minerals (alumina, bauxite,

rutile, rock phosphate, zircon, titanium dioxide, vermiculite) and production of eucalyptus hardwood

pulp and liner boards. Other subsidiaries were involved in woodchip production and ferrochrome

exportation. Essentially, these companies produced goods that fundamentally did not require large

investments in labour but in heavy machinery dependent on a limited threshold of human support.

There was a general agreement amongst a majority (90%) of those interviewed that Richards Bay’s

investments were largely capital intensive. A senior economist at one of the country’s investment

promotion departments bluntly indicated that ‘investments in Richards Bay and South Africa in general

[were] extremely capital intensive and thus essentially limited the scope of employment opportunities

they could generate’. This was congruent with Calagni (2003) argument that investment skewed in

natural resource extraction sectors limits linkages with local enterprise and constraints job creation.

Similarly, 86% of the participants involved in the two FGDs in eNseleni expressed the overall opinion that

existing firms, as they were, did not employ many people at any given time. At another FGD with

teachers at a local technical training institute in eNseleni, 78% participants agreed that the characteristic

capital intensiveness of the companies in the area had limited their capacity to employ more people.

Although accessing management in the MNCs was indeed a challenge, 90% of the MNC insiders

interviewed in confidence indicated as well that the nature of their businesses, the products and systems

were more efficient, profitable and competitive when capitally intensive and thus explained their

orientation towards lesser investment in manual labour.

These findings were confirmed when the asset base of each of the companies and their investment on

capital equipment and machinery was compared with the expenditure on human labour in the period

between 2000 and 2008. The MNCs massively invested on machinery that potentially limited their

capacity to create many jobs. On average the companies had up to R3, 000 worth of capital investment

for every single employee (World Bank, 2007; 2010). One MNC for example invested over R650 million in

a ferrochrome manufacturing plant and a further R400 million on expansion in the next year. It created

about 1, 000 jobs during the plant construction phase but contracted only 130 people for permanent

employment (World Bank, 2007; 2010; South Africa info, 2011).

Therefore, the implication was that Richards Bay had attracted significant investments that should in

principle have created sufficient jobs for the locals if the FDI‐employment‐poverty reduction discourse

fronted by the South African government was mechanistically followed. However, since investment

persisted in natural resource extraction, processing or beneficiation alone, which are sectors traditionally

characterised by production systems dependent on heavy machinery and a very limited scope of physical

manpower, the capacity of the MNCs to absorb more labour was equally restricted. The South African

government needed to actively attract more highly labour intensive manufacturing investments in order

to generate sufficient jobs to address the extent of unemployment in eNseleni. Otherwise FDI would not

6.2.2 Significant but weak Linkages between MNCs and local enterprises

In Tambunan (2005) framework, besides labour intensive investment, FDI could benefit the poor if MNCs

induce backward or forward linkages with local firms with the capacity to generate additional

employment. Unlike the question of capital or labour intensiveness, the idea of linkages was a rather

problematic one. It was important to establish that the MNCs actually did have business relations (of

some form) with domestic companies and then to understand the demeanour of such linkages and the

extent to which they thrived. This was important in judging the prospects of the linkages creating

employment but of what volume and of what character.

6.2.2.1 Significant Linkages

A majority of the respondents affirmed that the MNCs did have some form of business relations with

local enterprises. At least for every foreign owned company that was mentioned during the FGDs and

interviews, be it Mondi, BHP Billiton, RBM (Rio Tinto), Tata Steel, a list of local companies that reportedly

did business of some form with them was recorded. Business ranged from supply of raw materials (both

forward and backward), provision of security services, catering, HR services ‐ mostly executed by labour

contractors, to routine maintenance during annual ‘plant shut downs’. This was a notable illustration of

the arguments by Hirshman (1958) and Dunning (1992) that linkages create business opportunities

for local enterprise and open up new markets for SMMEs. The MNCs had induced some additional economic activity in the area which was a significant source of employment to the local population.

Incidentally, all those interviewed and 73% of FGD participants acknowledged that such local firms that

thrived on contracts and business relations with the MNCs were indeed an important source of

employment to many people in eNseleni.

‘They are keeping Richards Bay alive, if RBM closes tomorrow and Alusaf closes

tomorrow, then we are talking 90% of the population that work all out, those little

satellite businesses, the little welding shops, they will all close down because they are

all depending on the big companies’ (Participant, uMfolozi FGD, 21/08/2011)

‘They employ many people, half of the Richards Bay people [working population].

You do a survey, walk around and ask, you will find that over 70% of the people are

working there [the MNCs], the other 20% or 10% are working with the satellite

companies that get contracts from them, the service equipment people, the small

engineering firms, the zikizelas [small businesses]; they are all little ticks connected to

this big mother sheep of those three big foreign companies’ (Participant, uMfolozi

FGD, 21/08/2011)

‘Yes, there are so many people around here that we do business with. They supply

equipment, maintenance tools; like the guys who provide security ‐ they are not our

people, the cleaning guys are contracted from outside, the people who do catering at

the canteen are not our people, and we get some people who come to do projects

inside here that aren’t part of the company. All those are local companies that

wouldn’t exist if the big foreign companies did not locate here’ (Interview, MNC

insider, 19/08/2011)

‘The company being here employs a lot of people directly and also through the

enterprises that do business with us; like our contractors, people who do

maintenance, we have at least one ‘shutdown’ annually during which we need more

labour; local companies are contracted to do maintenance’ (Interview, MNC insider,

22/08/2011)

An example of such linkages (forward linkage) that emerged in almost every interview and FGD

was a local company that manufactured aluminium products. It sourced its raw material

(aluminium) from a MNC and produced goods that were sold locally. It was established that

government export policy that permitted export oriented MNCs to sell in the domestic market at

and sustained such forward linkages in profound ways. A senior officer at the Richards Bay

Industrial Development Zone also indicated that the existing MNC in the IDZ was indeed having

significant linkages with local enterprises: it procured some raw materials it utilized in producing

exported ferrochrome from domestic companies.

6.2.2.2Weak Linkages: unstable local enterprise – inability to absorb more labour

However, despite the evidence pointing immensely towards significant linkages – respondents

acknowledging and even mentioning credible instances demonstrating the existence of the linkages;

government officers confirming business relations between MNCs and local enterprises and the MNCs

themselves recounting the same ‐ the statistics was still evident; the high poverty levels, the acute

unemployment rates, the income inequalities and the human development indices were still real.

Following the discourse in a host of studies on FDI linkages and emp