Deciding on promotions and

redundancies

Promoting people by ability, experience,

gender and motivation

Adrian Furnham

Department of Psychology, University College London, London, UK, and

K.V. Petrides

Institute of Education, University of London, London, UK

Abstract

Purpose– To examine how people weigh information when making people decisions, specifically promotion or redundancy, at work.

Design/methodology/approach– A sample of 183 working adults completed two questionnaires that required them to rate 16 vignettes describing hypothetical people. They were devised to give combinations of the following: two gender (male/female), two levels of ability (average/high), two levels of work experience (less than five years/ more than 15 years) and two levels of motivation (average/high). The first questionnaire required participants to rate the 16 people for possible promotion and the second for possible redundancy

Findings– Participants favoured males over females; the more over the less experienced; the more over the less able/intelligence and the more over the less motivated for promotion and to be retained rather than made redundant. Employee motivation was seen to be the most important individual difference variable in the decision making.

Practical implications– Managers have to make many people decisions such as who to promote. They usually have to balance and weigh different pieces of information about people regarding that decision. This study shows that three factors were rated as particularly important namely experience, intelligence and motivation.

Originality/value– This study appears to be the first to examine decision making through this traditional vignette methodology. While it has drawbacks it also has advantages to investigate how people weigh information about others when trying to make important people decisions.

KeywordsExperience, Gender, Motivation (psychology), Promotion, Redundancy

Paper typeResearch paper

Introduction

One of the occasional tasks of a manager is to decide on who in their reporting staff to promote as well as, where applicable, who to make redundant. In large organisations there may be guidelines concerning which factors both to take into consideration (i.e. experience/service) and/or what to ignore (e.g. gender). Further some organisations keep records on performance which are designed to reduce the subjectivity in these sorts of decisions (Shipper and Davy, 2002). Nevertheless this is always a difficult decision because of the many and powerful consequences not only for the individual involved, but also his/her working colleagues and the organisation as a whole.

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0268-3946.htm

JMP

21,1

6

Received December 2004 Revised August 2005 Revised September 2005 Accepted September 2005

Journal of Managerial Psychology Vol. 21 No. 1, 2006

pp. 6-18

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited 0268-3946

Making promotion and redundancy decisions nearly always involves taking different factors into account such as an employees ability, motivation and experience. This study focuses on four such factors: an employees gender; their ability (intelligence/skill); their motivation (hard-work, conscientiousness) and their length of service or experience in the job. While there is a vast literature on job selection there is very little on decision making concerning specifically promotions and redundancies. This study uses vignettes of hypothetical people to study decision making of this kind which has been used frequently (London and Stumpt, 1982; Sessa and Taylor, 2000). There are a number of theoretically overlapping areas with respect to this study. One is the extensive literature on organisational justice, which itself encompasses various specific theories like equity theory, procedural justice theory, justice judgement theory and allocation preference theory (Greenberg, 1996). While the research on distributive justice is less relevant to this study, that on procedural justice certainly is. Greenberg (1996) has noted that judgements of procedural justice at work are strongly influenced by two factors: the interpersonal treatment people receive from decision makers (i.e. honesty, courtesy, timely feedback, respect for rights) as well as an adequate explanation of decisions. It appears that there are different criteria affecting the perceived fairness of treatment including evidence that decision makers adequately considered others’ viewpoints; they attempted to suppress personal bias; they were consistent in applying criteria; they gave timely feedback about their decisions and that they explained the basis for decisions. In short decisions need to be adequately reasoned and sincerely communicated.

Selection and redundancy decision have an impact not only the person making the decision and on the person who is the subject of the decision making but all employees in an organisation. They have expectations of how these decisions are made because they no doubt can and will effect how they are treated in due course. Selection, promotion and redundancy decisions represent clear examples of organisational justice at work. In some organisations there are clear guidelines about how procedures should be adhered to, whereas in others much more idiosyncratic factors are at work including the personality, experiences and ethical values of the decision maker.

They noted that the results suggested that:

1. Job irrelevant variables often are used in managerial selection decisions and may be more important than job-relevant variables.

2. Managerial selection decision models are complex and involve configural cue processing.

3. Managers’ personal demographics may be the most important variables in starting salary recommendations for managers (and possibly other professionals).

4. Significant effects were found for applicant sex in starting salary recommendations after controlling for human capital variables.

These results, is substantiated by further research, have important implications for the processes and outcomes of decisions regarding selecting professionals and their initial salary determinations (Greenberg, 1996, p. 60).

There is a significant research literature concerning how best to classify managerial traits and skills (Yau and Sculli, 1990). Over the past decade particularly in applied and human resource circles it has become popular to talk about management competencies (Boyatzis, 1982; Dulewicz and Herbert, 1999), a concept first made popular by

Promotions and

redundancies

McClelland (1973). There are however serious conceptual problems with the concept of competency which has led many to reject it in favour of more traditional and distinct concepts like ability and personality (Furnham, 2001; Moloney, 1997).

There is also a salient literature on the characteristics people look for when selecting others to work with, and for, them (Furnham, 2002). However, the most relevant and salient literature for this study concerns the perceived fairness/equity in promotion practices. McEnrue (1989, p. 816) noted that “researchers have never looked at promotion practices” and that semi-relevant research that has been done has been “from the perspective of the decision maker”. In her studies she demonstrated that procedural and distributive justice factors had a powerful influence on the perceived justice of promotions. More recently Bajdo and Dickson (2001) showed that both national and organisational culture variables effected how, when and why females were promoted. There is also a great deal of work on related issues like the psychological contract and the new shape of careers in the twenty-first century (Furnham, 2005).

As well as gender, studies have considered how decisions makers take race into consideration when deciding on promotions (Harrison et al., 1998). Powell and Butterfield (2002) proposed a promotion decision-making theory which made two central assumptions. First, individuals base their decisions on one or more pieces of information or cues. Second, individuals combine these cues in some manner to reach their decisions. The cues relevant to this study include personal characteristics of applicants “qualifications such as their education, work experience and current level in the organisational hierarchy” (Powell and Butterfield, 2002, pp. 399-400). Their study focused on gender and race but they did find years at the highest grade, highest degree obtained and performance appraisal did not effect selection decisions. However, they did record that:

It should be noted that other subjective or objective measures of applicants’ credentials (e.g. job-relevant knowledge, skills, abilities, or experiences they had) that were not assessed may have influences promotion decision outcomes (Powell and Butterfield, 2002, p. 422).

Kacmaret al.(1994) asked students from difference race groups in America to view four video tapes of a white female, white male, black female and black male who were supposedly applying for a job. They tested the assumption that giving participants job-relevant information has a positive effect on minority candidates. They found that having job-relevant information prior to an interview did improve the ratings for Black (minority) applicants but that these did not translate into more hire decisions. Their results concur with those of Hittet al. (1982) who found Black females significantly more responses to resumes sent to Fortune500 firms, but that they did not have a higher probability of actually being hired.

In a similar earlier study Hitt and Barr (1989) asked participants to view 16 applicants who differed in age, sex, race, job experience, education and level of job for which they were applying. They found that job-irrelevant variables were used heavily in selection decisions and that their decision models were complex. Blacks were rated lower than whites, women lower than men but there was no evidence of age discrimination. They found managers differentiate between applicants with complex but precise cognitive models based on prototypes. Thus a Black, 45 year old female

JMP

21,1

with ten years of salient experience and a master’s degree is viewed quite differently from a white, 35 year old man with identical experience and education.

In a retrospective, path-analytic study focusing on gender differences in managerial advancement Tharenonet al.(1994) found, predictably, that training led to managerial advancement and that this particularly favoured men. It was also more advantageous for men rather than women to have greater work experience and education. The path co-efficient for men showed that training and development was the best predictor of managerial advancement and that three factors that predicted it were work experience, education and self-confidence. However, this study was not on decision making but the actual pathways to managerial success.

This study is concerned with the weighting people use in making difficult managerial decisions. It is based on a methodology used to examine the decision to allocate scarce medical resources across medical conditions, using effect sizes primarily as the outcome criteria. Furnham, Thomson and McClelland (2002) examined how participants used data on hypothetical patients age, income, childlessness and smoking habits to rank order them for three types of operations: kidney dialysis, IVF and organ transplants. This involves rank-ordering individuals who differ systematically on a number of variables often set up in a factorial design. In this study participants were given two questionnaires that described 16 hypothetical employees (see Table I for how it was done in this study). As in the various medical studies the interest was focused on the relative influence of the four factors (Furnham, Hassomal and McClelland, 2002).

In this study four individual difference factors will be considered in two semi-identical studies. The first is sex. Because of both increasing sensitivity to gender discrimination but also the relative power of the other individual difference variance it is predicted that sex will not have a significant main effect for either decisions about promotions (H1a) or redundancies (H1b). The second factor was work experience as measured by years of service with the company. It was predicted that this factor would be highly significant in both causes with those with more experience/service (.15 yrs) being more likely to be chosen for promotion (H2a) and less likely to be chosen for redundancy (H2b). The third factor was ability/intelligence and it was predicted that this would be important for both promotion and redundancy decisions. It was predicted that the more able would be selected over the less able for promotion (H3a) but the other way around for redundancy (H3b). The final and probably most important factor was motivation/conscientiousness. It was predicted the more motivated would, compared to the less motivated, be chosen for promotion (H4a) but the other way around for redundancy (H4b).

With regard to effect sizes for main effects was concerned it was predicted that in both decision categories (promotion, redundancy) the rank order for the four factors would be motivation, then ability, then experience, then gender (H5). No formal hypotheses for interactions were made.

Method Participants

A total of 183 individuals participated in the study, of whom 75 were male and 106 female (two unreported). The mean age for the sample was 36.89 years (SD¼13:92

Promotions and

redundancies

Redundancy Promotion

Candidates X SD X SD

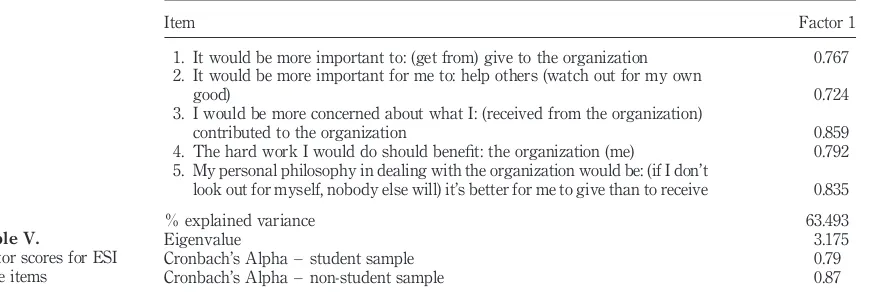

1. John who has been 17 years with the company, of average intelligence, ability and skill; who is very

hard working and motivated 4.89 1.46 4.69 1.24 2. Sarah, with very high ability and intelligence; an

employee for three years; and who is average with

respect to motivation and hard work 2.86 1.17 2.78 0.99 3. Philip, who is very driven, hard-working and

motivated, who has been 19 years with you, of

average abilities, skills and intelligence 4.24 1.47 4.45 1.20 4. Anne, who has worked 41

2years with the company;

who has exceptional abilities and skills, and who is

very average in motivation, drive and hard work 2.68 1.31 3.25 1.07 5. David, who has been with you 15 years, of normal

average ability and skill; and with tremendous

motivation and capacity for hard work 3.18 1.58 2.35 1.09 6. Louise, of average drive and motivation, an

employee for exactly two years and with very high

ability, intelligence and skill 2.48 1.21 2.34 1.01 7. Peter, who is very driven, hard working and

self-motivated, who has been working with you for 16 years and has pretty average skills, ability and

intellect 3.12 1.27 2.98 0.94

8. Alison, a relative newcomer, who has been 18 months with you, has exceptional ability, intelligence and skills, and who is average in her drive and

motivation 4.35 1.32 4.07 1.10

9. Christopher, one of your most long-serving employees of 40 years with strictly average skills, intelligence and ability; and with tremendous drive,

motivation and capacity for hard work 3.35 1.52 3.29 1.50 10. Joan, who has worked at the company five years, has

very high intelligence, ability and skills, and who has

average drive, motivation and hard-work practice 4.84 1.59 4.87 1.35 11. Henry, of average skills at the job, ability and

intelligence, who has very high motivation, tendency to hard work and drive, who has been in service here

18 years 5.88 1.42 6.07 1.15

12. Julia, who has been employed for three years; who has very high skill, ability and intelligence and who is clearly average in capacity for hard work and skill

motivation 5.94 1.59 6.14 1.23

13. Adrian, with average intelligence, job skills, ability, who has worked 19 years for your company, and is

very motivated, driven and hard working 5.47 1.45 4.66 1.22 14. Susan, who has been with you just under three years;

has very high skills, ability and intelligence; and also of average drive, capacity for hard work and

years). The majority of participants did not have a university degree (77.6 per cent). The sample was inclusive with respect to marital status, with 35.3 per cent of participants being single, 38.3 per cent married, 14.5 per cent cohabiting, 7.5 per cent divorced and 3 per cent widowed. All were working and had either managerial or supervisory experiences; that if they were in positions of authority that involved making serious decisions about others such as promotions.

Questionnaire

Participants completed a three part questionnaire. In the first part (deciding on redundancies) they were given a grid that described 16 people (see Table I). Their instructions were as follows:

We want you to imagine that you own and run a successful company that employs around 120 people. The current economic situation has caused a major crisis and you have no other option than to make staff redundant. Following your instructions your HR director has drawn up a list of 16 people she wants you to rate for how important it is to keep them.

You are asked to rate each one according to how much they need to be retained. Read each one and then indicate the priority to keeping them. The lower the score (i.e. 1 Very Low, or 2 Low) the more you feel they are good candidates for possible redundancy, while the higher the score (6 Extremely High, 7 Absolutely Crucial to keep) the less you feel they should be considered for redundancy.

The second part was a mirror of the first except participants were asked to decide on promoting rather than making employees redundant. The instructions for the other questionnaire were:

Deciding on promotions – We want you to imagine that you own and run a successful company that employs around 120 people. Every so often people apply for promotion and it is your final decision who gets promotion. Following your instruction your HR director has drawn up a list of 16 people she wants you to rate for promotion to a middle management position. You are asked to rate each one. Read each of the very brief descriptions of each one and then indicate the extent to which you believe they deserve promotion. The higher your score the higher your priority rating of promoting that person.

The two questionnaires were part of a larger booklet of inventories and separated by four others. Participants were told not to “turn back” when completing the

Redundancy Promotion

Candidates X SD X SD

15. William, an employee of exactly 16 years; with great motivation and drive and with average ability,

intelligence and skill 3.05 1.33 3.16 1.08 16. Gillian, of average motivational status, capacity for

drive and tendency to be hard-working, who has been working for your company for just under five

years who has high ability, intelligence and skill 2.26 1.30 1.90 0.93

Notes:1¼Very Low; 7¼Absolutely crucial. The names of the individuals were different in the two questionnaires. Common, familiar, first names that traditionally were given either only to males and females were used. Pilot work ensured all participants immediately know the gender of the target

person Table I.

Promotions and

redundancies

questionnaire. The third part of the questionnaire asked participants to complete personal details.

Procedure. A London-based market research company was asked to obtain 200 British managerial level adults of working age. They were inevitably therefore not a random sample s all had to be both at work and in positions of leadership. They were tested throughout the country and offered a small incentive to complete the questionnaires. Questionnaires were delivered on one day and collected on the next and remained anonymous. In all 190 of these collected were usable in the research (95.0 per cent response rate).

Results Promotions

The analysis of variance had both main effects for the four person factors and interactions. These will be discussed separately.

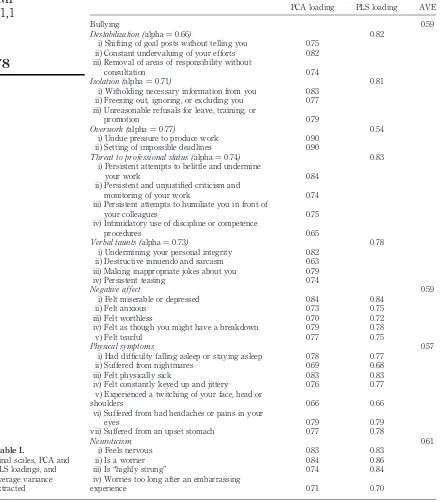

Main effects.The data were analysed through a two (gender) by two (high versus low experience) by two (high versus low intelligence) by two (high versus low motivation) repeated measures ANOVA. Table I presents the main effects, interactions and corresponding effect sizes, which indicate the amount of variance explained by each factor. Participants favoured males (M¼3:88, SE¼0:04) over females (M¼3:78, SE¼0:04), the more experienced (M¼4:39, SE¼0:04) over the less experienced (M¼3:27, SE¼0:05), the more able/intelligent (M¼4:56, SE¼0:04) over the less able/intelligent (M¼3:10, SE¼0:05) and the motivated (M¼4:59, SE¼0:05) over the less motivated employees (M¼3:07, SE¼0:04).

Interactions. There were a number of statistically significant interactions (see Table II) all of which were ordinal. For “gender by experience”, simple main effects analysis indicated that more experienced employees were preferred for promotion across genders, however, the effect has somewhat stronger for females than for males (eta sq:males ¼0:569, eta sq:fem¼0:659). For “gender by intelligence”, simple main effects analysis revealed that while the highly intelligent were preferred across

Source df F Effect size

Gender (G) 1,177 11.38* 0.06

Experience (E) 348.03* 0.66

Intelligence (I) 552.77* 0.76

Motivation (M) 641.45* 0.78

G £ E 2,176 17.80* 0.09

G £ I 8.54* 0.25

E £ I 131.24* 0.43

G £ M 28.02* 0.14

E £ M 21.11* 0.11

I £ M 1.14* 0.00

G £ E £ I 3,175 43.93* 0.19

G £ E £ M 2.29* 0.01

G £ I £ M 0.54* 0.00

E £ I £ M 18.25* 0.09

G £ E £ I £ M 4,174 20.22* 0.10

Note:*p,0:001

Table II.

Results of repeated measures ANOVA for promotions

JMP

21,1

genders, the effect was somewhat stronger for males than for females (eta sq:males ¼0:742, eta sq:fem¼0:646). For “gender by motivation”, simple main effects analysis indicated that the highly motivated were preferred across genders, but the effect was somewhat stronger for females (eta sq:males¼0:668, eta sq:fem¼0:809). For “experience by intelligence”, simple main effects analysis indicated that while highly intelligent employees were consistently favoured, the effect was somewhat stronger for the more experienced (eta sq:exp¼0:763, eta sq:inexp:¼0:647). Last, for “experience by motivation”, simple main effects analysis showed that the highly motivated were consistently preferred, although the effect was somewhat stronger for the more experienced employees (eta sq:exp¼0:745, eta sq:inexp:¼0:641). Overall, the interactions did not modify the substantive interpretation of the main effects.

Redundancies

Main effects.A similar ANOVA was set up to analyse the redundancy ratings (see Table III). Table II shows the main effects, interactions and corresponding effect sizes for this analysis. Data were coded such that higher scores indicate lower priority for making someone redundant. In contrast to the findings on promotions, gender did not reach significance levels in this analysis. The other three main effects were all statistically significant. Participants prioritised for redundancy the inexperienced (M¼3:33, SE¼0:06) over the experienced (M¼4:61, SE¼0:07), the less intelligent (M¼3:39, SE¼0:06) over the more intelligent (M¼4:54, SE¼0:06), and less motivated (M¼3:21, SE¼0:05) over the motivated (M¼4:73, SE¼0:08).

Interactions. In this analysis too, all significant interactions were ordinal. For “gender by experience”, simple main effects analysis revealed that less experienced employees were prioritised for redundancy across genders, however, the effect was slightly stronger for females than for males (eta sq:males¼0:465, eta sq:fem¼0:502). For “gender by intelligence”, simple main effects analysis showed that the less intelligent were prioritised for redundancy across genders, however, the effect was

Source df F Effect size

Gender (G) 1,175 0.87 0.00

Experience (E) 204.16* 0.54

Intelligence (I) 209.00* 0.54

Motivation (M) 306.73* 0.64

G £ E 2,174 6.83* 0.04

G £ I 29.45* 0.14

E £ I 8.34* 0.04

G £ M 2.28* 0.01

E £ M 34.44* 0.16

I £ M 4.61* 0.03

G £ E £ I 3,173 6.64* 0.04

G £ E £ M 9.76* 0.05

G £ I £ M 10.60* 0.06

E £ I £ M 46.80* 0.21

G £ E £ I £ M 7.34* 0.04

Note:*p,0:001

Table III.

Results of repeated measures ANOVA for redundancies

Promotions and

redundancies

much stronger for males than for females (eta sq:males ¼0:602, eta sq:fem¼0:323). For “experience by intelligence”, simple main effects analysis revealed that while the less intelligent were consistently prioritised for redundancy, the effects was somewhat stronger for less experienced employees (eta sq:exp ¼0:425, eta sq:inexp:¼0:535). For “experience by motivation,” simple main effects analysis showed that while the less motivated were consistently prioritised for redundancy, the effect was somewhat stronger for the more experienced employees (eta sq:exp¼0:596, eta sq:inexp:¼0:497). Last, for “intelligence by motivation”, simple main effects analysis showed that while the less motivated were consistently prioritised for redundancy, the effect was somewhat stronger for more intelligent employees (eta sq:high IQ¼0:594, eta sq:low IQ:¼0:527). As was the case with the promotion ratings, the interactions did not modify the substantive interpretation of the main effects.

Discussion

Many managers at all levels frequently but privately express difficulty in making both promotion and redundancy decisions: both because it involved hard choices with considerable disappointment expressed by those experiencing the less favourable options. Naturally they also complain that redundancy decisions are much harder than promotional decisions for obvious reasons. They know that their decisions have an impact on the particular individual concerned but also his/her workgroup who often try to understand the reasons behind the decision and whether they concur with organisational policy and their perceptions of procedural justice. The concept of fair is central to the issues around organisational justice and the psychological contract. However how managers combine and weight information as they come up with a final decision is not always clear to themselves, the candidate and the general workgroup (Hitt and Barr, 1989).

It is apparent from Table I that respondents made clear distinctions between the 16 candidates and that the preferences were similar in both exercises. Indeed the rank order correlation between the two exercises wasr¼0:94. The major discrepancy lay between candidates 4 and 5 where the “trade-off” was between ability and motivation. For redundancy, ability seemed more important than motivation, while for promotion the opposite was true.

Most, but not all of the hypotheses were confirmed. Interestingly H1a was not confirmed whileH1bwas confirmed. That is, despite legislation to the contrary, there was gender discrimination in choice of candidates for promotion (but not redundancy) with males more likely to be chosen. Interesting where previous studies have been shown significant gender effects, and most have not, there has consistently been a bias towards favouring males (Hitt and Barr, 1989). Further the gender interactions were also significant showing that respondents were clearly making decisions on the basis of gender as well as experience, intelligence and motivation. The gender £ experience and gender £ motivation significant interactions showed females being favoured over males but the opposite was true for gender £ ability/intelligence. Interestingly, the second highest effect size in the two way interactions for promotions was the gender £ intelligence interaction which showed a male advantage. Nearly all the studies in this area have shown that people try to combine and weight information so it is not unexpected that interactions have big effect sizes. Thus it appears that when it comes

JMP

21,1

to promotion, males particularly those thought to be bright were favoured over females.

With regard to redundancy decisions, the main effect for gender was not significant. However, the gender £ intelligence interaction (with the second biggest effect size) in the two-way interactions showed a sex effect such that less intelligent males were more likely to be made redundant than less intelligent females.

The second set of hypotheses (H2a; H2b) regarding work experience were confirmed, both in main effects and interactions. As expected the more experienced were preferred for promotion and being retained (rather than being made redundant) over the less experienced. Three observations are important here. First as a main effect experience was less important than ability/intelligence or motivation, particularly the latter. Next in the interactions experience together with ability/intelligence seemed particularly important from a promotions perspective but little experience with poor motivation seemed particularly important from a redundancy point of view. Third, the way experience was operationalised in this study was years of service which is easy to measure. Experience of the job, the company or the product is, inevitably, a more difficult to measure concept.

The third set of hypotheses (H3a;H3b) referred to the role of ability/intelligence in decision making. The words abilities/skills and intelligence were used interchangeably in the vignettes. Predictably the variable lead to significant differences with moderate effect sizes. The able were more likely to be chosen for promotion and to stay than those of average ability. Interestingly the gender interactions went in opposite directions. More intelligent males were more likely to be promoted and less intelligent males were more likely to be made redundant than more intelligent and less intelligent females respectively.

The fourth set of hypotheses (H4a;H4b) referred to the effect of motivation. For both decisions (promotions and redundancy) this variable accounted for most of the variance being observable by the effect sizes in Tables I and II. The more motivated (with synonymous terms of drive and hard work) the more they were likely to be chosen for promotion and retaining. While the interaction with intelligence was significant it showed small effect sizes for both decisions but in interactions with experience it was thought of as very desirable.

The interactions indicate that although results go in the same direction the effect sizes show a slightly different set of priorities. For promotions the interaction of experience and ability/intelligence (E £ I) seem most important but for redundancies it is experience and motivation (E £ M).

It is probably true to say that none of these findings was particularly surprising or counter-intuitive. What was perhaps most interesting and less easy to predict were the effect sizes or the amount of weight given to the various factors. The factor most easy to measure objectively, namely experience, was rated slightly less importantly than intelligence (but equal for redundancies) but the most important factor namely motivation is clearly the most complex and the most difficult to assess. Presumably those who manage others and are primarily responsible for making promotion and redundancy decision do have reliable data or such things as productivity, commitment and absenteeism which together with others behaviours make up the concept of motivation. It is not possible to do direct comparisons with other studies because thee are so few in this area, particularly examining the specific variables focused on here.

Promotions and

redundancies

For instance this study did not focus on education and qualification (Powell and Butterfield, 2002), nor did it examine race (Kacmaret al., 1994). But it did confirm that men with experience were rated more highly than women with experience (Tharenon et al., 1994). Many of the studies in this area have pointed out that people attempt to obtain then process various pieces of information in making their decisions but that often they are influenced by facts other than the seemingly obvious variables like job knowledge, skills, experiences or abilities. One advantage of the vignette technique used in this study is that by providing focused and minimalist information one can control for the information received by the participant.

There are both limitations of this study as well as implications for practice and research. This study used the minimal information vignette technique. While this is used in many decision making contexts including the many social judgement tasks in the Tajfel tradition (Hewstoneet al., 1982) it has obvious limitations. First it restricts the possibly saliency of other information that maybe taken into consideration in these decisions. The researcher is always in a dilemma of being able to provide unconfounded stimuli to ensure comparison and rich, everyday data that makes experimental research very problematic. Interestingly a dozen participants were questioned after to study on what they thought about it. When asked if there seemed any crucial data was missing a few suggested that personality and attitude factors may have played a part in their decisions. All those interviewed said that the task was a difficult one and took them quite some time to make their decisions but that it was quite realistic. Two in fact said that they had been engaged in precisely this type of task over the past few months.

The study called for ratings, rather than ranking, though of course the latter can be derived from the former, but not vice versa. This was done to enable multivariate statistics to be used and was a lesson learnt from the allocation of scarce medical resources research (Furnhamet al., 2002). However it is debatable as to whether people actually do rankings or ratings when making these decisions.

These days difficult decisions which may easily attract litigation are done not by individuals but by committees. These committees may be tasked to follow very particular processes and they may have the power to call for various criteria like appraisal data, absenteeism figures or records of productivity before making decisions. The more process driven and procedurally justice oriented the organisation the more likely the fact that decision making is pre- and pro-scribed.

Managers who made these decisions nearly always have to trade off various qualities or traits. Should one reward effort more than ability; or ability over long service? There are within and between employee decisions that have to be made as well as considering the consequences of those who are not beneficiaries or losers of the decision. The data from this study seemed to suggest that a candidate’s perceived motivation, more than their work experience (and loyalty) and their ability/intelligence were important in these decisions. In this study motivation was operationalised in terms of things like drive and capacity for hard work which is perhaps relatively easy to assess. Years of service are straight forward to assess, but intelligence/ability and motivation/conscientiousness more difficult. Yet it does seem participants believe job motivation even more important than these other factors.

This study suggests various other potentially important research avenues. The first is the effect on decision maker variables: that is their demographic (age, sex, education)

JMP

21,1

and psychographic (e.g. work attitudes, management level) correlates of these type of decisions. That is how does the biography, of the manager who makes the decisions, impact on those decisions. The second is whether these decisions are very distinctly a function of job type and level: that is whether the type of job people do strongly influences the relative power of certain factors (i.e. experience versus ability).

Thus some jobs may be very knowledge based, others skills based. Some may require high levels of intellectual processing while others may be more reliant on emotional rather than cognitive intelligence. In some jobs years of experience may be a distinct advantage while in others experience may peak earlier.

Certainly the topic of managerial decisions making about people is an important one with very clear theoretical and applied ramifications.

References

Bajdo, L. and Dickson, M. (2001), “Perceptions of organizational culture and women’s advancement in organizations”,Sex Roles, Vol. 45 Nos 5-6, pp. 399-414.

Boyatzis, R. (1982), The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance, Wiley, New York, NY.

Dulewicz, V. and Herbert, P. (1999), “Predicting advancement to senior management from competencies and personality data”,British Journal of Management, Vol. 10, pp. 13-22. Furnham, A. (2001),Management Competency Frameworks, CRF, London.

Furnham, A. (2002), “Rating a boss, a colleague and a subordinate”,Journal of Management Psychology, Vol. 17, pp. 655-71.

Furnham, A. (2005),The Psychology of Behaviour at Work, Psychologist Press, London. Furnham, A., Hassomal, A. and McClelland, A. (2002), “A cross-cultural investigation of the

factors and biases involved in the allocation of scarce medical resources”,Journal of Health Psychology, Vol. 7, pp. 381-91.

Furnham, A., Thomson, K. and McClelland, A. (2002), “The allocation of scarce medical resources across medical conditions”,Psychology and Psychotherapy, Vol. 75, pp. 189-203.

Greenberg, J. (1996),The Quest for Justice on the Job, Sage, London.

Harrison, D., Price, K. and Bell, M. (1998), “Beyond relational demography”, Academy of

Management Journal, Vol. 41, pp. 96-107.

Hewstone, M., Argyle, M. and Furnham, A. (1982), “Favouritism, fairness and joint profit in long-term relationships”,European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 12, pp. 283-96. Hitt, M. and Barr, S. (1989), “Managerial selection decision models”, Journal of Applied

Psychology, Vol. 74, pp. 53-61.

Hitt, M., Zikmund, W. and Pickens, G. (1982), “Discrimination in industrial employment”,Work

and Occupations, Vol. 9, pp. 193-216.

Kacmar, K., Wayne, S. and Ratcliff, S. (1994), “An examination of automatic vs controlled information processing in the employment interview”,Sex Roles, Vol. 30, pp. 809-28. London, M. and Stumpt, S. (1982),Managing Careers, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA. McClelland, D. (1973), “Testing for competency rather than intelligence”,American Psychologist,

Vol. 28, pp. 1-14.

McEnrue, M. (1989), “The perceived fairness of managerial promotion practices”, Human Relations, Vol. 42, pp. 815-27.

Moloney, K. (1997), “Why competency may not be enough”,Competency, Vol. 5, pp. 33-7.

Promotions and

redundancies

Powell, G. and Butterfield, D. (2002), “Exploring the influence of decision makers race and gender on actual promotions to top management”,Personnel Psychology, Vol. 55, pp. 397-428. Sessa, V. and Taylor, J. (2000), Executive Selection: A Systematic Approach for Success,

Jossey-Bass, New York, NY.

Shipper, F. and Davy, J. (2002), “A model and investigation of managerial skills, employees’ attitudes, and managerial performance”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 13, pp. 95-120. Tharenon, P., Latimer, A. and Conney, D. (1994), “How do you make it to the top?”,Academy of

Management Journal, Vol. 37, pp. 899-931.

Yau, W. and Sculli, P. (1990), “Managerial traits and skills”,Journal of Management.

Further reading

Rousseau, D. (1995),Psychological Contracts in Organisations, Sage, London.

Corresponding author

Adrian Furnham can be contacted at: a.furnham@ucl.ac.uk

JMP

21,1

18

The moderating role of

individual-difference variables in

compensation research

James M. Pappas and Karen E. Flaherty

William S. Spears School of Business, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater,

Oklahoma, USA

Abstract

Purpose– To examine the influence of company-imposed reward systems on the motivation levels of salespeople.

Design/methodology/approach– Data were collected from 214 business-to-business salespeople. In order to assure the adequacy of the survey instrument, several salespeople were recruited to “pretest” the questionnaire. To test the potential moderating influence of career stage on pay mix and valence, expectancy, and instrumentality estimates, a split-group analysis was performed. To test the moderating hypotheses for risk, we used two-step regression models in which the dependent measures (i.e. valence, expectancy, and instrumentality) were first regressed on the predictor variables as main effects, and then regressed on the multiplicative interaction term along with the main effects.

Findings– Support was found for many of the hypotheses. In particular, individual-level variables such as career stage and risk preferences moderate the relationship between pay mix and valence for the reward, expectancy perceptions, and instrumentality perceptions.

Practical implications– Managers must acknowledge that certain salespeople respond positively to fixed salary plans while others respond positively to incentive. In the past, managers might have relied on the salesperson to select the appropriate job for them. Salespeople are not “weeding” themselves out during the recruitment process. As a result, greater importance must be placed on human resource and sales managers during the time of recruitment.

Originality/value– There already exists a robust stream of literature on person-organization fit that suggests that employees prefer to work for companies that are compatible with their personalities. There is an increasing amount of work in multi-level research that suggests bridging the macro (organizational) and micro (individual) perspectives will enable researchers to make linkages between research streams that are commonly viewed as unconnected.

KeywordsPay structures, Career development, Risk assessment

Paper typeResearch paper

For many organizations, salespeople provide a unique opportunity for a sustainable competitive advantage. As boundary spanners, salespeople link the organization to its customers. They often have access to divergent information coming from important customer groups. Furthermore, they, as unique human resources, are less susceptible to imitation and more durable than other types of organizational resources (Barney, 1991). Given the important role salespeople play, motivation of the sales force is widely recognized as an essential component of organizational strategy (Pullins, 2001; Alonzo, 1998). In response, sales firms have created, implemented, and continue to adjust company policies and procedures in attempts to boost motivation levels among salespeople. Policies related to the compensation of the sales force provide a continued source of discussion surrounding the issue of motivation. In this research, we jointly

consider the influence of compensation policy (set at the firm level) and individual-difference variables on salesperson motivation.

Despite the attention sales compensation issues have received in both the management and marketing literature, gaps still exist. Much of the past work on compensation has focused on identifying the consequences or outcomes of compensation (e.g. Gerhart and Milkovich, 1990; Kahn and Sherer, 1990). While these studies have looked at the main effect of pay mix on performance, they do not explicitly study moderators of the effectiveness of the pay mix. Other compensation studies have focused on identifying antecedents of pay mix, suggesting that strategic patterns exist. For instance, pay mix has been shown to vary based on a host of corporate factors (i.e. the corporation’s diversification strategy, growth strategy, maintenance strategy) (Balkin and Gomez-Mejia, 1990).

More recently, compensation research has taken a turn toward studying potential contingencies or moderators. Both researchers and practitioners have become increasingly concerned with the big picture, acknowledging that “cookie cutter” compensation systems will not work (Barber and Bretz, 2000; Gerhart and Milkovich, 1990; Gomez-Mejia and Balkin, 1992). In response, several studies examine potential moderators of the relationship between compensation and performance (Balkin and Gomez-Mejia, 1990; Gomez-Mejia, 1992). However, this research has focused mostly on SBU-level and corporate-level moderators, paying considerably less attention to individual-difference variables.

The lack of attention to individual-level differences in reactions to pay is troubling for two reasons. First, there is a robust stream of literature on person-organization fit that suggests that employees prefer to work for companies that are compatible with their personalities (Kristof, 1996).

To the extent that individuals differ in preferences, values, and personalities, their reactions to compensation practices should also differ. We therefore believe there is much to be gained by studying compensation’s role in attraction and retention from a fit perspective (Barber and Bretz, 2000, p.37).

Second, there is an increasing amount of work in multi-level research that suggests bridging the macro (organizational) and micro (individual) perspectives will enable researchers to make linkages between research streams that are commonly viewed as unconnected (Kleinet al., 1999).

Taking this approach, we empirically investigate the influence of individual-level characteristics, including career development and risk attitudes, on the relationship between pay mix and salesperson motivation. Compensation strategy decisions regarding pay level (total earnings generated) and pay mix (relative proportion of variable pay to fixed pay) are both vital in sales compensation. In this study, we focus on pay mix because pay level tends to reflect industry patterns, while pay mix is more a function of the marketing efforts of the firm. As such, competing firms most likely have similar pay level policies but different pay mix choices (Balkin and Gomez-Mejia, 1992). Notably, recent research in the sales literature has moved towards studying compensation as one element within a broader control system, including supervisor’s style of monitoring, directing, and evaluating the sales force. However, we evaluate pay mix as a single element, because we are interested in understanding the interplay between formal firm-level policy and the individual employee. This study provides an exploratory test of one possible example of this interaction.

JMP

21,1

Theoretical framework

In previous organizational research, agency theory has been widely applied when studying the pay-performance relationship (e.g. Bloom and Milkovich, 1998; Gerhart and Milkovich, 1990). A key limitation to the agency theory approach is that the agents are automatically assumed to be risk-averse; therefore, the full-range of employee attitudes and behaviors may not be captured (Bloom and Milkovich, 1998). More recently researchers in this area (e.g. Rynes and Gerhart, 2000) have suggested using motivational theories including expectancy theory to further our understanding of compensation programs.

The expectancy theory framework proposes that an individual’s motivation is comprised of three components:

(1) expectancy of performance or estimates of the probability that effort will affect performance;

(2) instrumentality or estimates of how strongly performance is believed to lead to reward; and

(3) valence for rewards or measures of an individual’s desire for the reward.

Ultimately, the three components combine to affect the salesperson’s motivation (e.g. Cronet al., 1988; Walkeret al., 1977).

The majority of research based in the expectancy theory framework has focused on identifying variables that influence valences, expectancies, and/or instrumentalities. Most of this work specifically examines task or organization-level variables, rather than individual-level variables. Of the studies that have focused on individual-level variables, most focus solely on reward valences (e.g. Ingram and Bellenger, 1983; Churchillet al., 1979).

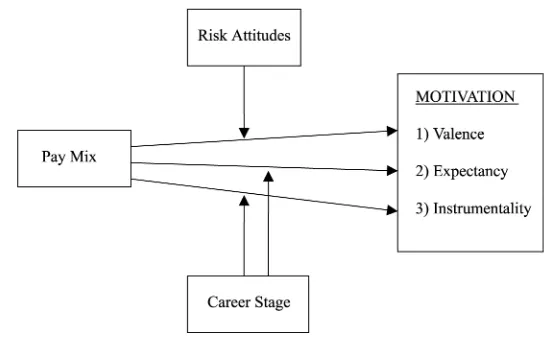

We extend the past research by providing an examination of the role individual differences play in determining salesperson motivation across valences, expectancies, and instrumentalities, and by considering how individual differences between salespeople influence reactions to firm policy (in this case pay mix). We expect that individual-level variables, including the career stage and risk attitudes of the salesperson, will have a moderating impact on pay mix. Hypotheses concerning the moderating role these variables play in the compensation – motivation relationship are now discussed (see Figure 1).

Career stage

In the past decade, the notion of career development (and with it career stages) has changed dramatically. While, traditionally, careers were believed to evolve within one or two firms in a very linear pattern, today we recognize that this is rarely the case. Due to increases in technology along with other environmental factors, firms have downsized and restructured in order to achieve greater flexibility. As a result, many workers have lost jobs and been forced to follow different career paths (e.g. Feldman, 1996).

Sullivan (1999) provides a thought provoking discussion of the changes occurring in careers and the implications of these changes on research based in career stage theory. In particular, Sullivan addresses the question of whether or not past theories of career stages and operationalizations of the career stage construct adequately encompass today’s career reality. For instance, Super’s (1957) theory suggests that individuals

Individual-difference

variables

reflect their self-concept through vocational choices that can be summarized in four stages:

(1) exploration; (2) establishment; (3) maintenance; and (4) disengagement.

Super’s theory has been operationalized in a number of ways. Researchers have used age, length of tenure, and a variety of other inconsistent measures of the stages across studies (e.g. Sullivan, 1999). Sullivan suggests that this prior research does not effectively account for the “recycling” (i.e. returning to the issues of early career stages) indicative of today’s career landscape. For instance, studies using age as a proxy of career stage certainly point to the possible misidentification of employees who have not followed a traditional career path. For example, an older salesperson may suddenly enter a new industry or of a former manager may change careers and enter sales for the first time at an older age.

In light of the growing importance being placed on career stage, we evaluate the construct in this study. To effectively capture the “recycling” nuances of careers, we implement a self-selection measure of career stage. Respondents were asked to read four passages corresponding to each of the four career stages defined in the work of Cron and his colleagues (Cron and Slocum, 1986; Cronet al., 1988) and to self-select a stage. This procedure for measuring career stage has been used in more recent sales research (Flaherty and Pappas, 2002). Instead of relying on age or tenure measures, employees are free to select a stage based on their current career concerns.

Based in Cron’s (1984) work salespeople in the exploration stage are most concerned with finding a job where they feel comfortable. Commitment to the job is likely to be low because the salesperson is still exploring career options. Performance is also likely to be low at this time. Salespeople in establishment have begun to make a commitment to a certain occupation. They are now concerned with securing a solid position in this particular occupation. As such, they tend to be higher performers, and they are also Figure 1.

Hypothesized relationships

JMP

21,1

concerned with promotion opportunities. In maintenance, salespeople continue to perform at a high level (Cron and Slocum, 1986), although desire for promotion diminishes (Slocum and Cron, 1985). Finally, salespeople in disengagement are characterized as “psychologically separating” from the job. They are no longer committed to the career, and tend to be lower performers (Cron and Slocum, 1986). Refer to the Appendix for the specific self-selection passages viewed by respondents.

Statement of hypotheses

In the following discussion, we present study hypotheses. Our hypotheses are broken into two distinct sections. First, we focus on the interplay between the individual-level variables and company pay mix. The individual-level variables are expected to affect the relationship between pay mix and motivation in very different ways. For instance, we argue that career stage will interact with pay mix to affect expectancies and instrumentalities of the salespeople. Second, we argue that risk attitudes are expected to interact with pay mix to affect valences for pay increases.

Career stage and pay mix

Cronet al.(1988) hypothesized that career stage influences the valences, expectancies, and instrumentalities of salespeople and found support for some of the hypotheses. However, they did not consider possible interactions between career stage and the organization’s pay mix. On the basis of this literature, as well as compensation research and expectancy theory, we develop several hypotheses concerning salespeople’s valences for pay increases, expectancies, and instrumentalities in each career stage and with different pay mix policies.

Valence. Valence refers to the emotional orientations people hold with respect to rewards such as money, promotions, or even satisfaction (Vroom, 1964). According to expectancy theory, rewards may be intrinsic to the salesperson (e.g. personal development) or they may be extrinsic rewards (e.g. pay increases, promotion, and recognition). Past research indicates that valences for rewards influence the effectiveness of alternative compensation programs (Lee, 1998). This work has looked at valence for reward as a possible moderator in this relationship.

Past research examining the influence of career stage on reward valences has not been fully supported (e.g. Cronet al., 1988). Not surprisingly, an organization’s pay policy or governance structure may supersede the influence of an individual’s career stage on valence for rewards. For instance, if a salesperson in the exploration stage of his or her career, takes a sales position that offers a pay mix consisting solely of commission and other incentives, it is most likely that this salesperson would report a strong desire for lower order rewards (e.g. pay increases). This salesperson is currently in a situation where incentives, and thus pay increases, are emphasized, so it is logical to expect this salesperson to desire pay increases. Conversely, if working for a company that offers a fixed salary, a salesperson may be more likely to report a desire for intrinsic rewards instead of pay increases. In this case, incentives are not stressed by the company; therefore, the desire for pay increase may be reduced. In short, the organization’s pay mix, or other factors, may have more of a direct affect on salespeople’s valences for pay increases. Based on this discussion, as well as past research, an interaction between career stage and pay mix is not expected.

Individual-difference

variables

Expectancy. Expectancy refers to the salesperson’s perceptions of the link between effort and performance. Past research has hypothesized that expectancy estimates are higher in the higher performing career stages of establishment and maintenance (Cron et al., 1988). Interestingly, empirical findings did not support this hypothesis. Here, we propose an interaction between the career stage and the organization’s pay mix. We suggest that the construct of “performance” is at least in part defined by the organization. A pay mix high in fixed salary may communicate to the salesperson that the behavioral elements of the job (e.g. service to customers, paperwork, etc.) are important elements of performance as well. Meanwhile, a pay mix focused mostly on incentives may convey that output equals performance.

Past research shows that salespeople’s levels of output performance are typically lower during exploration and disengagement and higher during establishment and maintenance (Cron and Slocum, 1986). Salespeople in exploration and disengagement most likely do not feel confident that their effort is linked closely to output-based performance. Given that variable pay is linked directly to output performance, salespeople in exploration and disengagement are likely to have lower expectancy perceptions when the company’s pay mix is focused around variable pay. If the company’s pay mix consisted of mostly fixed salary, expectancies might change. Again, the assumption here is that the pay mix is not focused solely on output performance, so definitions of performance, held by the salespeople, may be different. In the case of the higher performing salespeople in the establishment or maintenance stages, tying compensation to performance is likely to result in perceived benefits. By defining performance in terms of output, the company promotes increased expectancy estimates among these salespeople.

In summary, the following hypotheses are put forth.

H1a. During exploration, an increase in variable pay will be negatively associated with expectancy estimates.

H1b. During establishment, an increase in variable pay will be positively associated with expectancy estimates.

H1c. During maintenance, an increase in variable pay will be positively associated with expectancy estimates.

H1d. During disengagement, an increase in variable pay will be negatively associated with expectancy estimates.

Instrumentality. Instrumentality refers to the salesperson’s perceptions that additional rewards will be obtained with increased performance. Again past career stage research has shown that career stage is related to instrumentality estimates; however, this work does not consider the interaction with pay mix. Cronet al.(1988) found that salespeople in exploration have lower instrumentality estimates than salespeople in establishment. Further, salespeople in disengagement have lower instrumentality estimates than salespeople in maintenance. The prevailing logic is that as a person becomes more involved with the job and the organization, they are likely to become internalized leading to stronger instrumentality estimates. Commitment and performance are higher in establishment and maintenance and lower in exploration and disengagement, thus the findings of Cron and colleagues support this logic.

JMP

21,1

Extending this notion, we suggest that career stage also moderates the influence that the organization’s pay mix has on the resulting instrumentalities. Given that instrumentality estimates vary by career stage, the tying of compensation to output performance rather than purely fixed salary is expected to hold certain implications. If a salesperson is not a high performer, a variable pay mix is expected to result in decreased instrumentality estimates. However, if the salesperson is a high performer, a variable pay mix is expected to result in increased instrumentality estimates.

H2a. During exploration, an increase in variable pay will be negatively associated with instrumentality estimates.

H2b. During establishment, an increase in variable pay will be positively associated with instrumentality estimates.

H2c. During maintenance, an increase in variable pay will be positively associated with instrumentality estimates.

H2d. During disengagement, an increase in variable pay will be negatively associated with instrumentality estimates.

Career stages and risk attitudes

A second characteristic of the individual salesperson that is anticipated to have a moderating impact on compensation strategy is risk. Contrary to the traditional thinking of agency theory, research has found that aversion to risk varies across individuals (Yates and Stone, 1992). Some individuals are risk averse, others are risk neutral, and still others are risk seekers. Additional research indicates that preference for variable pay versus a fixed salary differs depending on risk preferences (Cable and Judge, 1994). The focus on how risk preference leads to differing preferences for certain pay designs leads to questions concerning how risk preference interacts with pay design to influence outcomes of the employee (Wisemanet al., 2000).

Valence. Commission by its very nature presents more risk for the salesperson and appeals to risk seekers. On the other hand, salary provides more security and less risk and thus appeals to the risk averse. A risk seeker is likely to have different valences for variable versus fixed pay than the risk averse. A risk seeker is expected to have a greater desire for rewards that are tied to performance, while a risk averse salesperson is expected to have a greater desire for rewards that are stable. Thus, the salesperson’s attitude toward risk is also expected to interact with the organization’s pay mix to affect valences for pay increases. Ordinarily when a company institutes a pay policy focused on variable pay the desired result is to increase valences for pay increases. However, if the salesperson is risk averse, we expect that the variable pay policy may not result in the desired effect. Conversely, if the salesperson is a risk seeker, we expect that a variable pay policy will in fact result in increased valences for pay increases.

H3a. When a salesperson is a risk seeker, increased variable pay is positively associated with valences for pay increases.

H3b. When a salesperson is risk averse, increased variable pay is negatively associated with valences for pay increases.

Individual-difference

variables

Expectancy and instrumentality. Unlike career stage, risk attitudes are not expected to have an impact on expectancies and instrumentalities. While an organization’s focus on a certain pay mix communicates that output performance or behavioral performance is more or less important, a salesperson’s natural inclination towards risk is not likely to matter. A salesperson’s perceptions that added effort will result in higher performance will not change based on whether or not they seek risk. Thus, an interaction between risk attitudes and pay mix is not hypothesized for expectancies or instrumentalities.

Empirical study

The purpose of this study is to test whether or not career stage and risk moderate the relationship between pay mix and the components of salesperson motivation (valence, expectancy, and instrumentality).

Sample and procedure

A total sample of 1,000 salespeople was drawn from a membership list acquired through a national (US) list broker. The sample was further limited to business-to-business salespeople operating in service organizations. Consistent with the process set forth by the Dillman (1976) method, surveys were mailed to each salesperson with an attached cover letter. The actual questionnaire was preceded by an introduction letter sent out one week prior to the mailing of the questionnaire. In total, 214 surveys were received for a response rate of 21.4 per cent.

Measures

Most measures were taken from or adapted from existing studies. Risk attitudes were measured using the job preference inventory scale (Williams, 1965). To measure career stage, respondents were asked to read four passages corresponding to each of the four career stages defined in the work of Cron and his colleagues (Cron and Slocum, 1986; Cronet al., 1988) and to self-select a stage. Refer to the Appendix for a listing of the passages. This procedure for measuring career stage has been used in more recent sales research (Flaherty and Pappas, 2002). The self-selection measure is useful in terms of capturing the latest trends in career research as well. Instead of relying on age or tenure measures, this method calls for employees to self-select a stage based on their current career concerns allowing for the possibility of “recycling” (see Sullivan, 1999). Older employees re-entering the work force as first time salespeople or in a new sales industry, may feel they fall most closely under the exploration stage. If we were to base this decision on age, a inaccurate categorization would result.

As a measure of pay mix, respondents were asked to indicate the percentage of total pay that they receive in the form of incentives (including all commissions, bonuses, etc.). Finally, to measure valences for pay increases, expectancies, and instrumentalities, the method followed by Cron et al. (1988) was adapted. In this study, valences for pay increases were of particular interest, and thus was the only reward valence evaluated. Refer to the Appendix for sample items.

Control measures

A variety of factors that have been shown to hold implications for compensation strategy in other research (but are beyond the scope of this study) were controlled.

JMP

21,1

These include age, size of the firm, pay level (the salesperson’s total income) and market prominence.

In order to assure the adequacy of the survey instrument, several salespeople were recruited to “pretest” the questionnaire. Six sales representatives from a local service provider were asked to complete the survey. On completion, they were asked to provide suggestions and feedback concerning the instrument. At this point, an additional question was added to the questionnaire. This question required respondents to indicate whether their job responsibilities include “actual selling of services” or “more customer service related activity”. Based on this response, those salespeople who perform very little selling duties were eliminated from the sample (13 questionnaires).

Sample profile

Respondents ranged in age from 24 to 72. The average age of the sample was 43. Notably, a few older than expected salespeople were included in the sample, with the oldest salesperson reporting an age of 72. Also, the majority of respondents were male (77 percent, m, 23 percent, f). Salespeople in each of the career stages were represented in the sample, however fewer reported being in the last stage of disengagement. Specifically, 23 percent reported being in exploration, 31 percent reported being in establishment, 30 percent reported being in maintenance, and 13 percent reported being in disengagement. Due to the low response rate of respondents in disengagement, we could not conduct robust tests of this career stage. Previous research has indicated the importance of the disengagement phase (Cronet al., 1993) and we feel that it is an important area of future research.

Analysis

To test the hypothesized relationships, we performed the following tests. First, we mean-centered the data by replacing values with deviations from the means. This was done to reduce the presence of multi-collinearity in the equations (Cohen and Cohen, 1983). To test the potential moderating influence of career stage on pay mix and valence, expectancy, and instrumentality estimates (H1a-H1d), a split-group analysis was performed. The split-group analysis tests differences between groups, where the regression is estimated twice, once for each group, and then the regression coefficients are compared. Given the hypotheses in question, the following regression equations were estimated, once across the exploration and disengagement stages and again across the establishment and maintenance stages:

Valence¼aþb1pay mixþb2riskþb3ageþb4pay level Expectancy¼aþb1pay mixþb2riskþb3ageþb4pay level Instrumentality¼aþb1pay mixþb2riskþb3ageþb4pay level

Exploration and disengagement were pooled due to consistent expectations (i.e. variable pay is associated with decreases in expectancies and instrumentalities). Likewise, establishment and maintenance were pooled based on consistent expectations (i.e. variable pay will be associated with increased expectancies and instrumentalities).

To test the moderating hypotheses for risk, we used two-step regression models in which the dependent measures (i.e. valence, expectancy, and instrumentality) were first

Individual-difference

variables

regressed on the predictor variables as main effects, and then regressed on the multiplicative interaction term along with the main effects. Finally, we computed the difference in theR2s of the equation testing the main effects and the equation including the interaction term. Again, this process was followed for each dependent variable.

We tested for the influence of control variables (i.e. age, size of the firm, market prominence, and pay level) in the following manner: First, we correlated them with the predictor and criterion variables in the model (Ancona and Caldwell, 1992). Then, we entered the control variables in all regression equations. The variables did not change the pattern or significance of results. Thus, in the remainder of this section, we report the regression results without the control variables in order to preserve power.

Results

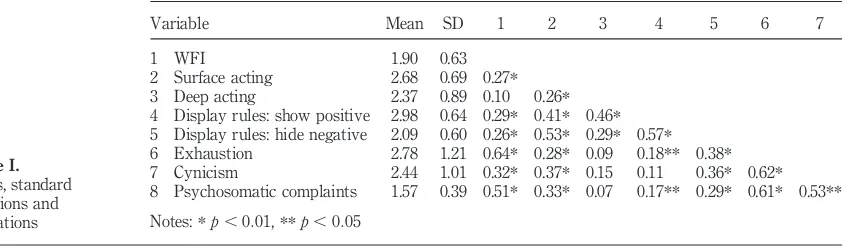

Correlations, means, and standard deviations of study variables are provided in Table I. Results of the split group analysis and moderated regression analysis are presented in Table II and Table III respectively. A discussion of key findings follows.

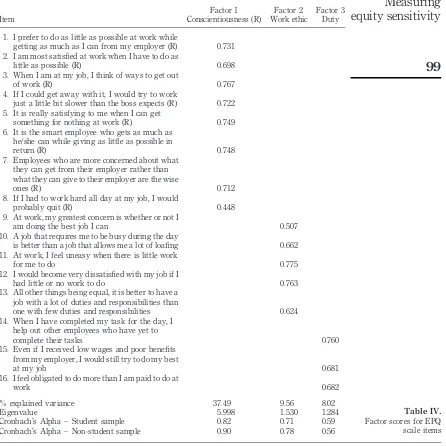

Results of the split group analysis (Table II) indicate that career stage moderates the influence of pay mix on expectancy and instrumentality estimates of the salespeople. As expected, findings show that a pay mix reflecting greater variable pay results in a significant negative effect on instrumentality estimates (b¼20:221, p,0:05) and expectancy estimates (b¼20:300, p,0:05) for salespeople in exploration. Conversely, variable pay has a significant positive influence on instrumentality and expectancy estimates for salespeople in establishment (b¼0:240, p,0:05 and

ðb¼0:288, p,0:05, respectively), as well as a positive significant influence on instrumentality and expectancy estimates for salespeople in maintenance (b¼0:297, p,0:05 andðb¼0:314,p,0:05, respectively). In addition, Chow tests measuring the differences between the regression coefficients for expectancy and instrumentality estimates were highly significant for the exploration versus establishment groups (F¼0:206, p,0:01, and F¼0:199, p,0:01 respectively) and for the exploration versus maintenance groups (F¼0:271, p,0:01, and F¼0:217, p,0:01 respectively).

The plotted interaction effects in Figure 2 provide a consistent picture of the results provided above. The outcome scores were plotted at the mean of the proportion of variable pay (pay mix). One standard deviation below the mean represents less variable pay, while one standard deviation above the mean represents greater variable pay. In general, the slope was steeper for employees in the exploration phase. Analyses of the slopes confirm results of the split group analysis.

Results of the moderated regression analysis indicate that the risk attitudes of the salesperson have a significant influence on the relationship between pay mix and valences for pay increases. Consistent with our hypotheses, the interaction between risk and pay mix was significant (b¼0:48,p,0:01). The change inR2when adding the interaction term to the equation was also significant (DR2¼0:09,p,0:05). Discussion and implications

Study results suggest that career stage and risk preferences impact the relationship between compensation and the three components of motivation. These results go past existing knowledge suggesting that type of compensation alone does not dictate the effectiveness of the program. Results reported here indicate that organizations need to

JMP

21,1

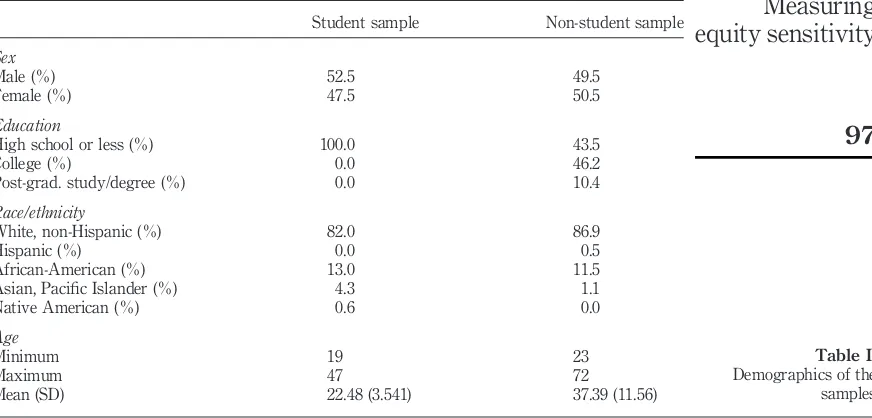

Variable Mean SD. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1. Career stage 2.61 0.52

2. Risk preferences 6.70 0.83 0.29 (0.88)

3. Pay mixa 41.1 3.84 0.13 0.20

4. Valence for pay increase 3.69 0.61 0.16 0.34* 0.19 (0.73)

5. Expectancy estimate 2.75 0.87 0.22 0.17 20.16 0.09 (0.72)

6. Instrumentality estimate 2.58 0.83 0.11 0.22 0.10 0.16 0.56* (0.81)

7. Age 43 9.61 0.39* 20.16 0.21 0.36* 0.19 0.27*

8. Pay level (total income in thousands) 52.6 102.3 0.41* 0.13 0.51* 0.29* 0.18 0.19 0.63*

Notes:aTotal per cent of variable pay received; *p,0:05

Table

I.

Correlations

among

variables

(coefficient

alphas

for

multi-item

scales

are

reported

along

the

diagonal)