www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Social hierarchy in the domestic goat: effect on

food habits and production

F.G. Barroso

a,), C.L. Alados, J. Boza

a

Departamento Biologıa Aplicada, Uni´ Õersidad de Almerıa, 04120 Almerıa, Spain´ ´ Accepted 9 February 2000

Abstract

Outside the scientific world, the effect of social behaviour on production is little taken into account, but the importance of this relationship has been sufficiently proven in some animal species. Nevertheless, there are scarce works that emphasise the importance of behaviour in the production of the goat. The main objective of this paper is to determine if there is a stable hierarchy of dominance in a flock of goats fed in pasture, and if this hierarchy influences somehow the diet selected in the pasture and in its production of milk and meat. The study was carried out in a flock of goats in semi-extensive grazing management. The interactions observed in the pasture during the supplementary feeding and during the milking were written down. This allowed us to determine the dominance rank. The diet was determined in the pasture by the direct observation method. The production of milk was measured daily. The meat production consisted on the weight of the kids in their first day of life and after a month. Among the most prominent

Ž .

results, the following should be indicated: a Within the herd, a clearly established, quite stable

Ž .

and linear hierarchic order exists. b The most aggressive animals are those that occupy the

Ž .

highest positions within the social hierarchy. c Age, large size and horns seem to be the physical

Ž .

factors that most favor dominance. d When more forage becomes available, differences appear in the diet chosen by dominant and subordinate animals, that is, they become more selective. In the months of greater shortage, these differences in feeding disappear, and they become more

Ž .

generalist. e The production of animals is affected by dominance. However, contrary to what

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q34-50-21-52-94; fax:q34-50-21-54-76.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] F.G. Barroso .

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Ž .

might otherwise be thought, it is the middle range of goats that are the most productive.q2000

Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Dominance; Goat; Feeding and nutrition; Production; Social behaviour

1. Introduction

During the last 30 years, with the intensification of animal production, the animals’ way of life has become less and less natural. Research has been particularly devoted to problems concerning nutrition, reproduction and disease. Nevertheless, it is important for the mechanisms of animal behaviour to be well known so that efficient management techniques can be developed for optimum production as well as the animals’ welfare

ŽKolb, 1971; Bouissou, 1980 ..

Ž .

Kaufmann 1983 defined the dominancersubordinance behaviour as a relationship

Ž . Ž

between two individuals in which one the subordinate defers to the other the

.

dominant in contest situations. This relationship is often determined by a mutual assessment, which may range from simple recognition to ritualized displays or serious

Ž

fights. The concept of dominance has been continuously debated e.g. Rowell, 1966,

.

1974; Bernstein, 1970, 1976, 1981; Hinde, 1978, 1983; Barrette and Vandal, 1986 .

Ž

Although several authors tend to link social dominance with aggression Brown, 1975;

.

Wilson, 1975; Wittenberger, 1981; Alcock, 1984 , others consider that passive supplant-ing and avoidance are better indications of stable relationships, while fights are more

Ž .

likely to indicate disputed status Rowell, 1966 .

The social hierarchy permits successful coexistence in social communities. Social interactions between animals often involve some degree of conflict, and rank has a pronounced effect on the individual. Individuals of low status may suffer from reduced access to resources such as food, resting places, shade, mating, and general inhibition of activity. On the contrary, higher animals in a dominance order generally have priority

Ž

access to limited resources Fraser, 1974; Syme et al., 1975; Clutton-Brock and Harvey, 1976; Arnold and Dudzinski, 1978; Syme and Syme, 1979; Appleby, 1980; Bouissou, 1980; Reinhardt and Flood, 1983; Lynch et al., 1985; Bennett et al., 1985; Sherwin and

.

Jhonson, 1987; Alados and Escos, 1992 .

Ž

Some studies assert that dominance is a relatively mild phenomenon in goats Stewart

. Ž

and Scott, 1947; Scott, 1948 . This conclusion contrasts with that of others Pretorius,

.

1970; Schaller, 1977; Kilgour and Dalton, 1984; Hart, 1985 , who assert that there exists a clear structure of dominance in goat herds. Various projects that have attempted to relate social hierarchy to production have obtained some contradictory results. The effect of social rank on productivity can be considerable, depending on the species and type of

Ž .

management system Syme and Syme, 1979 .

on the feeding of animals and consequently in their production. This will allow taking of measures to improve the management of the flock, and therefore to increase their production and profitability.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Research area

The study was conducted at the ‘‘Los Pajares’’ experimental plot, a 130-ha area located in the Filabres mountain range, in the province of Almerıa, in southern Spain.

´

The area is a small valley with elevations ranging from 735 to 1025 m. The climate is semi-arid Mediterranean with a mean annual precipitation of about 324 mm. TheŽ .

vegetation climax is a ‘‘coscojal’’ Quercus coccifera , but the ‘‘Los Pajares’’

land-Ž .

scape shows the influence of agriculture. Robles 1990 distinguished six different kinds

Ž . Ž

of shrublands: ‘‘Albaidar’’ Anthyllis cytisoides , ‘‘Albaidar-Espartal’’ Stipa

tenacis-. Ž . Ž

sima and Anthyllis cytisoides , ‘‘Espartal’’ Stipa tenacissima ‘‘Romeral’’ Rosmarinus

. Ž . Ž .

officinalis , ‘‘Tomillar’’ Thymus baeticus , and ‘‘Aulagar’’ Ulex parÕiflorus .

2.2. Animals

The experimental flock was 90 head of ‘‘Granadina’’, ‘‘Malaguena’’ and ‘‘Serrana’’

˜

goats and their respective crossbreeds. Management was semi-extensive. The animals were released to graze during the day and returned to a closed shed at night. On returning from grazing, the animals were fed in a manger with a small amount of supplement.All the animals in the herd were earmarked with a numbered metal tag and measured

Žlength, height and thorax . A sample of 20 goats made up of animals from each age. Žfrom 2 years until more than 8 was chosen for observation..

2.3. Data compilation

Social behaviour was recorded between March 1988 and September 1989 using an

Ž .

‘‘all-occurrences’’ sampling method Altmann, 1974 . Most interaction data were

col-Ž .

lected during direct observation of grazing 7 hrday . Additional observations were

Ž .

made during morning milking 1 hrday and during afternoon feeding with concentrate

Ž .

in the manger 0.5 hrday . All animals had the same probabilities of being observed. The approximate total observation time during this experiment was 500 h. Every time an

Ž

interaction occurred, both the goats involved actor — the goat provoking the

interac-.

tion, and reactor — the goat subjected to the provocation were noted, and the type and the outcome of the interaction were recorded.

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Following Rowell 1966 , Struhsaker 1967 , Seyfarth 1980 and Lee 1983 , the assessment of interindividual competition was based on the direction of dyadic ap-proach–retreat interactions. The apap-proach–retreat hierarchies were considered to be

Ž

.

Rowell, 1974; Bernstein, 1976; Deag, 1977 , and an individual’s rank order was called its dominance rank.

Ž .

The antagonistic interactions considered were a ‘‘retreat’’: one animal moves away

Ž . Ž . Ž .

at the approach of another avoid or runs away when chased by another flight , and b

Ž .

‘‘approach’’: any of the following interactions: 1 ‘‘displacement’’: one animal walks

Ž .

steadily toward another, which retreats; 2 ‘‘supplant’’: one animal takes away another’s

Ž . Ž .

resources e.g., food or resting place ; 3 ‘‘threat’’: one animal directs its nose or horns

Ž .

towards another; 4 ‘‘aggression’’: one animal pokes its nose or horns towards another. An approach not accompanied by an antagonistic interaction was not considered in the

Ž .

determination of approach–retreat hierarchies Alados and Escos, 1992 .

The usual individual ranking method is to order the members of a group so as to

Ž

minimize the number of wins under the diagonal of an interaction matrix Schein and

.

Forhman, 1955; Brown, 1975; Lott, 1979 . This practice increases the overall impression

Ž .

of linearity by obscuring irregularities in hierarchies Beilharz and Mylrea, 1963 ,

Ž . Ž .

Appleby 1983 suggests a test adapted from Kendall 1962 , in which a significant result indicates that dominance among the animals studied is transitive more often than would be expected by chance. That is to say that if an animal ‘‘A’’ dominates another ‘‘B’’, and this ‘‘B’’ dominates ‘‘C’’, it is probable that ‘‘A’’ dominates ‘‘C’’.

Ž . Ž .

Dominance D was calculated for each individual, following Lamprecht 1986 :

Dsnumber of individuals subdominantr

Ž

number of individuals dominantqnumber of individuals subdominant

.

=100as the percent of animals dominated to all animals with which it has interacted. This

Ž .

method, previously used by Scott 1980 , establishes the rank of each individual better than the simple ‘‘number of individuals dominated’’. The rank of an individual depends

Ž .

on its performance in all the dyads contested Chase, 1985 , but dominance depends on

Ž .

its attributes relative to those interacting with it Barrette and Vandal, 1986 , the animals were grouped into three categories: high-ranking females with D)0.66, medium-rank-ing females with D between 0.33 and 0.66 and low-rankmedium-rank-ing females with D-0.33 to compute the effect of rank on feeding and production.

In order to study the relationship between the aggressive behaviour and the stress

Ž

situation, all the interactions were grouped in ‘‘active dominance’’ threats and

aggres-. Ž .

sive interactions and in ‘‘non-active dominance’’ retreat, supplant and displacement . The individual rate of aggression was calculated as the total number of threats and aggressions recorded for the subject divided by the total number of threats and aggressions recorded for the group.

The animals were observed directly to determine what they ate. The following

Ž . Ž . Ž .

information was recorded: a plant species, b part of the plant, c number of bites,

Ž .

and d type of shrubland where it occurred. Afterwards, approximately 300 bites of the most important species were cut by hand simulating the goat’s feeding habit. This was dried at 508C to determine the dry weight of a bite and analyze its nutritional intake.

kid was caught the day after its birth for marking and weighing. The identity of its mother was recorded. Weight was recorded again when it was 1 month old.

2.4. Analysis

BMDP statistical software was used for the statistical analysis.

The stability of the hierarchic order during the study was determined by Friedman

Ž .

variance analysis, applying an arcsine transformation Cohen and Cohen, 1983 to

Ž .

standardize the dominance rates D . The Appleby index was used to test the linearity of the hierarchy.

The comparisons between aggressiveness and dominance rank were made in two

Ž . Ž .

ways. 1 An analysis of variance ANOVA of the relationship between social rank and the rate of aggressions initiated and received. The aggression rates were reclassified as

Ž .

high, medium and low. 2 The differences in agonistic behaviour shown developed by

Ž . Ž .

the animals during grazing free feeding and in the stable milking and forced feeding

Ž

were tested by the chi-square method with one degree of freedom Sokal and Rohlf,

. Ž .

1969 , that is, the active dominance rate threat and aggression and non-active

Žavoidance, displacement and supplanting. were compared in these two situations Žshepherding–stable ..

Ž

ANOVA was used to test for the effect of individual characteristics age, length of

.

animals, and horns on social rank. Both age and size were reclassified as high, medium and low. Age was standardized by a logarithmic transformation according to Sokal and

Ž .

Rohlf 1969 to make variance independent of the mean and to make frequency

distribution skewed to the right more symmetrical.

ANOVA was also done for the relationship between hierarchy and intake of the most

Ž .

important plant groups in the diet shrub and herbaceous . Intake of each plant group was expressed as a percentage of the total intake, an arcsine transformation was used to

Ž .

standardize the dominance rates Cohen and Cohen, 1983 .

Ž .

An ANOVA of the relationship between social rank and productivity milk and meat was performed. Milk production is influenced by the age of the goat; goats from 4 to 6

Ž .

years 3rd and 5th lactation of age produce the most milk. This age group was the one observed for the effect of dominance on milk production, because it has the most homogeneous milk production.

3. Results

3.1. Social hierarchy

The study confirmed the existence of a well-defined hierarchy in a flock of domestic goats. Dominance relationships showed considerable stability throughout the period of

Ž 2 .

investigation Friedman variance analysis, Xr s0.60, psn.s. .

Ž

Results show a linear, although not perfect, hierarchy in female goats Appleby

2 .

index, Ks0.62, ds388.8, gls35, X s203.1, p-0.001 , with a few dyadic

Table 1

Ž .

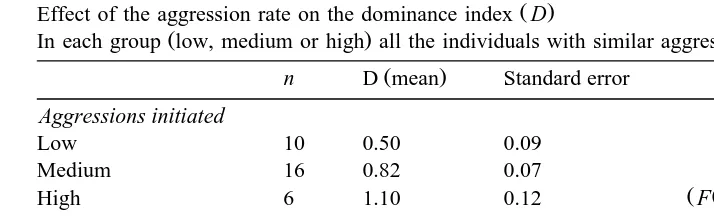

Effect of the aggression rate on the dominance index D

Ž . Ž .

In each group low, medium or high all the individuals with similar aggression have been grouped n .

Ž .

n D mean Standard error

Aggressions initiated

Low 10 0.50 0.09

Medium 16 0.82 0.07

Ž Ž . .

High 6 1.10 0.12 F 2,29s8.61, ps0.0012

Aggressions receiÕed

Low 5 1.12 0.12

Medium 14 0.91 0.07

Ž Ž . .

High 13 0.49 0.07 F 2,29s13.96, Ps0.0001

Ž . Ž .

individual dyads, 335 92% continued the linearity of the hierarchy, and 29 8% of these relationships were contrary to this social rank.

3.2. Aggression–dominance relationship

There was a positive relationship between the individual index of dominance and the

Ž Ž . .

rate of initiated aggression ANOVA, F 2,29 s8.61, ps0.0012 , whereas with the

Ž Ž . . Ž .

rate of received aggression it was negative F 2,29 s13.96, ps0.0001 Table 1 . Goats compete more for scarce resources. This is reflected in the difference between

Ž .

their interaction when competition is slight on pasture and that in highly competitive

Ž . Ž .

situations stable: e.g., milking, food supplement and place of rest Table 2 . The type

Ž 2

of dominance shown by the goats in these two areas is very different X s60.7,

. Ž .

p-0.001 ; the greatest part of their behaviour in the pasture is ‘‘passive’’ 75.5% , with only 24.5% of the interactions ‘‘actively’’ dominating. In the stable, on the contrary, the

Ž .

proportion of passive dominance was much lower 52% , with a notable increase in

Ž .

threats and aggression 48% .

3.3. Influence of physical characteristics on social rank

In this study, the length of the animal was measured, since measurement of the thorax is affected by the state of pregnancy, and height varies greatly with breed. The

Table 2

Ž . Ž .

Differences of behaviour with slight competition on pasture and high competition on stall

X2s60.7, p-0.001.

n indicates the total number of interactions observed in the pasture and in the stall.

Shepherding Stall

n % n %

Non-active dominance 369 75.5 278 52.0

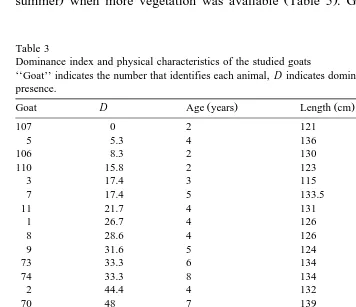

characteristics of the goats observed and their indices of dominance are indicated in Table 3.

Ž Ž . .

Rank is strongly determined by age F 2,23 s21.46, ps0.0000 , and by size

Ž ŽF 2,23.s13.17, ps0.0002. ŽTable 4 . The oldest and largest animals occupy the.

topmost positions in the social hierarchy.

Horns greatly affects rank. Horns determined the efficiency of the individual in competitive interaction, both threatening and in a fight. Animals with horns were

Ž Ž .

invariably found in the topmost positions in the herd hierarchy F 1,24 s0.0003,

. Ž .

ps0.0003 Table 4 .

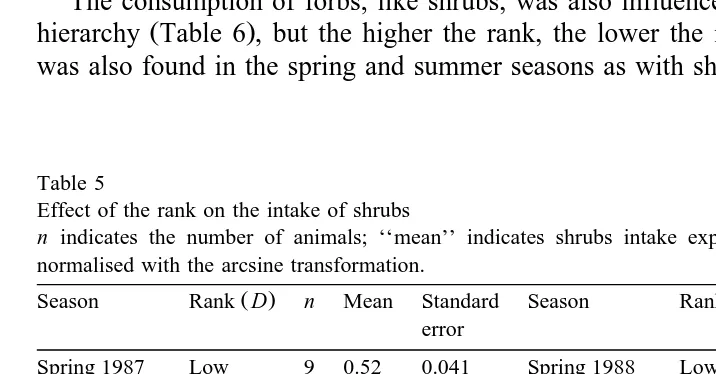

3.4. The effect of dominance on feeding

Ž

Shrub consumption was significantly related to rank in those seasons spring and

. Ž .

summer when more vegetation was available Table 5 . Goats from the low-ranking

Table 3

Dominance index and physical characteristics of the studied goats

‘‘Goat’’ indicates the number that identifies each animal, D indicates dominance index. Horns: A, absence, P, presence.

Ž . Ž .

Goat D Age years Length cm Horns

107 0 2 121 A

5 5.3 4 136 A

106 8.3 2 130 A

110 15.8 2 123 A

3 17.4 3 115 A

7 17.4 5 133.5 A

11 21.7 4 131 A

1 26.7 4 126 A

8 28.6 4 126 A

9 31.6 5 124 A

73 33.3 6 134 A

74 33.3 8 134 A

2 44.4 4 132 A

70 48 7 139 A

151 56 q8 135 A

181 56.5 q8 142 A

96 57.1 7 135 A

83 57.9 7 135 A

72 62.5 7 147 A

154 69.6 q8 132 A

71 72 6 139 A

80 75 6 145 A

12 76.9 7 125.5 P

90 76.9 6 135 A

156 78.6 q8 146 P

182 78.6 q8 131 P

91 92.6 7 139 P

95 93.1 8 141 P

Table 4

Ž .

Effect of the physical characteristics on the dominance index D

n indicates the total number of interactions.

Ž .

n D average ANOVA

Ž .

Age years

3–4 4 0.26

5–6 6 0.56

Ž .

7 to)8 16 0.98 F 2,23s21.46, ps0.0000

Ž .

Length cm

115–125 4 0.30

126–136 14 0.73

Ž .

137–147 8 1.07 F 2,23s13.17, ps0.0002

Horns

No 22 0.68

Ž .

Yes 4 1.30 F 1,24s18.11, ps0.0003

group consumed fewer shrubs than goats in the middle ranks, and goats in the highest ranks had the maximum intake.

The consumption of forbs, like shrubs, was also influenced by position in the social

Ž .

hierarchy Table 6 , but the higher the rank, the lower the intake of forbs. This result was also found in the spring and summer seasons as with shrubs.

Table 5

Effect of the rank on the intake of shrubs

n indicates the number of animals; ‘‘mean’’ indicates shrubs intake expressed in % of the total intake,

normalised with the arcsine transformation.

Ž . Ž .

Season Rank D n Mean Standard Season Rank D n Mean Standard

error error

Spring 1987 Low 9 0.52 0.041 Spring 1988 Low 9 0.69 0.044

Medium 3 0.51 0.071 Medium 5 0.69 0.058

High 8 0.67 0.044 High 6 0.90 0.053

Ž . Ž .

F 2,17s3.78, ps0.0439 F 2,17s4.99, ps0.0198

Summer 1987 Low 9 0.41 0.058 Summer 1988 Low 9 0.77 0.042

Medium 3 0.58 0.101 Medium 5 0.97 0.056

High 8 0.65 0.062 High 6 1.01 0.051

Ž . Ž .

F 2,17s4.25, ps0.0318 F 2,17s7.96, ps0.0036

Autumn 1987 Low 9 0.89 0.063 Autumn 1988 Low 7 0.80 0.057

Medium 4 0.97 0.094 Medium 7 0.82 0.057

High 7 0.88 0.071 High 6 0.83 0.062

Ž . Ž .

F 2,17s0.36, psn.s. F 2,17s0.06, psn.s.

Winter 1987 Low 9 0.73 0.088

Medium 4 0.83 0.132

High 7 0.85 0.100

Ž .

Table 6

Effect of the rank on the intake of forbs

n indicates the number of animals; ‘‘mean’’ indicates forbs intake expressed in % of the total intake,

normalised with the arcsine transformation.

Ž . Ž .

Season Rank D n Mean Standard Season Rank D n Mean Standard

error error

Spring 1987 Low 9 0.83 0.041 Spring 1988 Low 9 0.87 0.043

Medium 3 0.85 0.071 Medium 5 0.88 0.058

High 8 0.76 0.043 High 6 0.67 0.053

Ž . Ž .

F 2,17s1.01, psn.s. F 2,17s5.12, ps0.0182

Summer 1987 Low 9 1.14 0.061 Summer 1988 Low 9 0.79 0.043

Medium 3 0.97 0.105 Medium 5 0.60 0.058

High 8 0.86 0.064 High 6 0.54 0.053

Ž . Ž .

F 2,17s5.12, ps0.0182 F 2,17s7.33, ps0.0051

Autumn 1987 Low 9 0.34 0.047 Autumn 1988 Low 7 0.66 0.053

Medium 4 0.47 0.070 Medium 7 0.54 0.053

High 7 0.25 0.053 High 6 0.55 0.058

Ž . Ž .

F 2,17s3.19, ps0.0664 F 2,17s1.63, psn.s.

Winter 1987 Low 9 0.80 0.092

Medium 4 0.74 0.138

High 7 0.69 0.104

Ž .

F 2,17s0.28, psn.s.

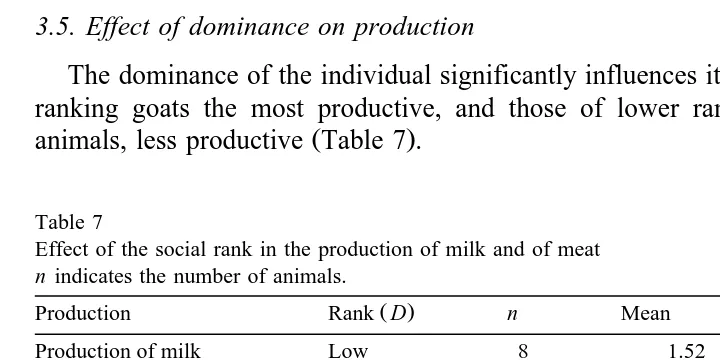

3.5. Effect of dominance on production

The dominance of the individual significantly influences its production, with middle-ranking goats the most productive, and those of lower rank, as well as high-status

Ž .

animals, less productive Table 7 .

Table 7

Effect of the social rank in the production of milk and of meat

n indicates the number of animals.

Ž .

Production Rank D n Mean Standard error

Production of milk Low 8 1.52 0.106

Žlrdayrgoat. Medium 31 1.74 0.054

High 9 1.49 0.099

Ž .

F 2,45s3.35, ps0.0439

No. kids Low 18 0.23 0.038

Medium 16 0.31 0.041

High 12 0.21 0.047

Ž .

F 2,43s1.53, psn.s

Ž .

Weight of all kids kg Low 18 4236 341

first day of life Medium 16 5616 362

High 12 4575 418

Ž .

F 2,43s4.05, ps0.0244

Ž .

Weight of all kids kg Low 18 10 385 794

first month of life Medium 12 13 792 972

High 10 12 035 1065

Ž .

Ž .

Production of meat was also affected by the social hierarchy Table 7 .

Middle-rank-Ž .

ing goats produced more meat adding the weight of all their breedings per birth

Ž5615.6 kgrgoat , followed from a distance by the high-ranking goats 4575.0 kg. Ž rgoat ,.

Ž .

and finally those of lower rank 4236.1 kgrgoat . Similar results were observed in 1-month-old suckling kids, with the kids of the middle-status goats again weighing more

Ž13729.2 kgrgoat , followed by those of uppermost rank 12035.0 kg. Ž rgoat , and finally.

Ž .

those lowest in the hierarchy 10384.7 kgrgoat . Though the middle-ranking goats also have the greatest number of kids per birth, the difference is not significant.

4. Discussion

4.1. Social hierarchy in the herd

This investigation clearly demonstrated the existence of a dominance–subordination relationship in the social organization of the domestic goat and confirmed the

observa-Ž . Ž . Ž .

tions of Marincowitz 1968 , Pretorius 1970 , and Addison and Baker 1982 . This hierarchy was quite stable, the animals maintaining their position throughout the months, though there are always some animals that experience slight changes of position within the herd.

Ž

Some investigators Dickson et al., 1967; Bouissou, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1980, in cows;

.

Ewbank and Meese, 1971, Reinhardt, 1985; Reinhardt and Flood, 1983, in bisons have pointed out how the dominance–subordination relationships established between two animals are very stable, most of them persisting for several years, although very infrequently, some of them may be reversed.

The hierarchic order has been observed to be linear, though not perfectly so, with an absolutely dominant animal and an absolutely dominated one. A significant result in the Appleby test indicates that dominance is transitive more often than would be expected by chance. Of all the relationships obtained from the individual dyads, 92% were consistent with the assumption of a linear dominance hierarchy, with only 8% reversals, generally in individuals dominating another of similar, though slightly higher, rank.

Ž . Ž .

Similarly, Egerton 1962 , in American bison, and Alados and Escos 1992 , in Dama gazelles, obtained 5.5% reversals.

4.2. Aggression–dominance relationship

The term aggressive behaviour, in the narrow sense, is reserved for behaviour that

Ž .

could cause physical injury to another animal Hart, 1985 . Antagonistic interactions between two animals engaged in establishing and maintaining their mutual dominance–

Ž .

subordinance status includes an array of actions Kondo and Hurnik, 1990 . The primary role of aggression in natural environments is to assure an adequate supply of scarce

Ž

resources to animals with high status when competing with their own kind Craig,

.

It has commonly been suggested that a function of ‘‘dominance’’ is to reduce

Ž .

aggression within the group Rowell, 1974; Gauthereaux, 1978; Syme and Syme, 1979 ,

Ž

because aggression consumes energy and increases physical harm to animals Syme and

.

Syme, 1979 . To establish its position in the hierarchy an animal has aggressive interaction with other members of the group, but once this position has been established, it is maintained for the most part without any need for physical confrontation, although

Ž .

reinforcement by physical threat, feint or butt is still necessary Canali et al., 1986 . However, even in stable groups, the dominance hierarchy does not prevent aggression

ŽSyme, 1974; Eccles and Shackleton, 1986; Alados and Escos, 1992 ..

In our study, the relationship between the social rank and rate of antagonistic interaction initiated was positive, while it was negative with the rate of antagonistic interaction received. This indicates that higher-ranking animals constantly reinforce their status by means of continuous aggression. This correlation between dominance position

Ž

and aggression has already been described Beilharz et al., 1966; Reinhardt, 1980; Reinhardt and Reinhardt, 1975; Reinhardt et al., 1987; Collis, 1976; Orgeur et al., 1990,

.

Wierenga, 1990; Alados and Escos, 1994 .

Several factors may have caused an increase in aggressive interactions in this study.

Ž .1 The acquisition by the shepherd of a small herd 35 head which he added to theŽ .

previous herd; the introduction of strange individuals to an established group usually causes a disruption of the group’s social structure, resulting in an increase of

ant-Ž .

agonistic behavior Brantas, 1968; Brakel and Leis, 1976; Barash, 1977 .

Ž .2 Goats were forced to feed simultaneously from the same limited amount of food

Ž

and space, which evidently led to a high degree of competition Brouns and Edwards,

.

1994 .

Ž .3 Goats were overcrowded in too small a stable, so that the individual animals did

Ž .

not have enough room. According to Bouissou 1981 , high levels of aggression among domestic animals may reflect the high stocking rates of modern intensive husbandry systems.

Ž .4 Milking was done in the stable with consequent disputes between the individuals

to be milked.

This fact is reinforced by the significant increase in antagonistic behaviour of the

Ž .

animals while in the stable 48% of interactions compared to during shepherding

Ž24.5% . These results point out the importance of the shepherd’s management in the.

welfare and production of the animals. Rarely in these poor areas is the owner of a herd able to make an important investment in the enclosure or development system. The animals are crowded together in old stables lacking the necessary space and sanitation, their grazing is supplemented in an insufficient number of feeding places, and they are milked in the same place where they rest. All this provokes more interaction than what there might be with the consequent risk of injury to the animals and reduction in

Ž .

production e.g., growth rate, milk production, etc. . In fact, it has been suggested that the housing conditions of the animals are adapted to man rather than to the animals

ŽRoss, 1960 ..

It has been assumed that there is little direct or interference competition for food

Ž .

within groups of grazing herbivores Kiley-Worthington, 1978; Wittenberger, 1981 .

Ž

Bouissou, 1980, 1981; Addison and Baker, 1982; Arnold and Grassia, 1983; Metz, 1983; Reinhardt and Flood, 1983; Wierenga, 1984; Kondo and Hurnik, 1990; Brouns

.

and Edwards, 1994 have observed that if an important resource, such as water, feed, or resting space becomes restricted, animals engage in physical forms of antagonistic interaction more than if the same resources are freely available.

4.3. Influence of physical characteristics on social rank

Among the problems that emerge from the study of social dominance in domestic

Ž .

animals, the effect of the individual characteristics age, size, horns has received much

Ž

attention, since they strongly influence ranks within a herd Bouissou, 1972, Syme and

.

Syme, 1979 .

The oldest and biggest goats occupy the highest positions in the social ranking. Age andror weight are positively correlated with social dominance in numerous ungulate

Ž

projects Scott, 1948; Ross and Scott, 1949; Schein and Forhman, 1955; Collias, 1956; Mchugh, 1958; Espmark, 1964; Bouissou, 1964, 1972, 1980; Candland and Bloomquist, 1965; Beilharz et al., 1966; Dickson et al., 1967; Marincowitz, 1968; Pretorius, 1970; Ozaga, 1972; Tyler, 1972; Clutton-Brock et al., 1976, 1982; Stricklin et al., 1980; Arave and Albright, 1981; Townsend and Bailey, 1981; Alados, 1983; Alados and Escos, 1992; Hall, 1983; Kilgour and Dalton, 1984; Reinhardt, 1985; Barrette and Vandal, 1986; Rutberg, 1986; Thouless and Guinness, 1986; Lott and Galland, 1987; Bartos et al.,

. Ž

1988; Enoksson, 1988; Locati and Lovari, 1991 . However, some authors Collis, 1976;

.

Lott, 1979; Eccles and Shackleton, 1986 have found no correlation. Thouless and

Ž .

Guinness 1986 suggest that many of these studies have looked at too small a number of individuals and included immature animals, invalidating the effects of age and weight.

Horns are very important in establishing a higher social rank. Because of this, the six goats with horns were between the first and seventh positions of the hierarchic order of the herd in our study. Horn and antler length have been correlated with social status in

Ž .

goats Ross and Scott, 1949; Collias, 1956; Hafez and Scott, 1962; Kolb, 1971 ,

Ž . Ž

mountain sheep Geist, 1966, 1971 , cervids Espmark, 1964; Geist, 1966; Lincoln et al.,

. Ž

1970; Kucera, 1978; Clutton-Brock, 1982, Barrette and Vandal, 1986 , chamois Locati

. Ž .

and Lovari, 1991 , and cows Bouissou, 1972 . However, other authors have not

Ž

obtained these results Eccles and Shackleton, 1986, for big horn sheep, Rutberg, 1986,

.

bison cows; Alados and Escos, 1992, or Dama gazelles .

4.4. Effect of dominance on feeding

Ž

The cost of living in society includes competition for food Alexander, 1974;

.

Kiley-Worthington, 1978 . This is made evident by the animals’ interference with each

Ž . Ž

other during shepherding Wilson, 1975 . Various investigators Dittus, 1977; Lincoln,

.

1972; Ekman and Askenmo, 1984; Brouns and Edwards, 1994 have observed that feeding is strongly related to the social rank of the individual, and the dominant

Ž .

Ž .

It has been known for years Davies, 1925; Jones, 1933; Stapledon, 1934 that the number of palatable species influences the degree of selectivity during shepherding. Selection of shrubs and grasses was influenced by rank at the beginning of both spring and summer. In these seasons, there is a greater offer of forage, since rains and temperatures are the most appropriate for plant growth. March 1987 was exceptional, possibly because of the extreme drought of the previous months, leaving scant forbs in the field.

Ž .

According to Schoener 1971 , an animal must adapt its feeding habits the best it can

Ž .

to adjust to a particular environment. Vivas and Saether 1987 point out that when the nutritive value of the plants diminishes, the animal has two options for covering its energy requirements: it can either increase the intake of food or it can reduce the cost of collection. It seems that abundance causes herbivores to tend towards specialization

ŽPyke et al., 1977 . When this abundance diminishes, ungulates widen their rank,. Ž

consuming less-preferred plants Macarthur and Pianka, 1966; Schoener, 1971; Emlen,

.

1973; Owen-Smith and Novellie, 1982; Belovsky, 1984 . It would therefore seem that energy invested in competitive interference for food increases when the quality of this

Ž .

food increases Shopland, 1987 .

In this study, the goats behaved as generalists in the months of less availability of

Ž .

food autumn and winter , since it is more advantageous for them to collect all the species they find. They do not dispute the most palatable, because this would spend more energy than that which the plant, normally of low nutritive value at this time of the year, would provide. On the contrary, when the forage offer is much greater and of

Ž .

better quality spring and summer , the goats behave as specialists, becoming more selective of the food to be ingested, and the higher ranking goats interfering with

Ž . Ž .

subordinates to obtain the most-preferred species shrubs . Barroso et al. 1995 also obtained that goats had a high preference for bushes.

Ž .

Thouless 1990 has identified two ways in which the feeding behavior of animals is

Ž .

affected by the identity of neighbouring individuals: a They are more likely to move

Ž .

away, and to stop feeding while doing so, if the neighbour is socially dominant. b They take fewer bites as the distance from dominant neighbours decreases. These results suggest that for grazers under natural conditions a more passive form of interference may be important.

Ž .

These results coincide with those obtained by other authors. Alados 1986 and

Ž . Ž .

Alados and Escos 1987 found that the Iberian goat Capra pyrenaica was more

Ž .

selective when the plants were abundant spring , and less selective when plants were

Ž . Ž .

less available winter . A similar result was found by Owen-Smith and Novellie 1982

Ž .

with the kudu, Warrick and Krausman 1987 with the mountain ewe, and Vivas and

Ž . Ž .

Saether 1987 with the moose Alces alces .

4.5. Effect of dominance on production

Direct physical injury is perhaps the least important consequence of farm-animal

Ž .

aggression Fraser and Rushen, 1987 . Aggressive behaviour can have profound effects

Ž .

Ž

consequence of aggressive interactions. Other authors Dantzer and Mormede, 1979;

.

Siegel, 1980 have observed a reduction in productivity due to increased stress.

Ž

Social rank had a clear effect on production of milk and of meat weight of suckling

.

kids in the first day of life and at 1 month of life . However, and to the contrary of what might otherwise be thought, it is not the most dominant goats that were the most productive, but those located in the middle positions. Intermediate-ranked goat may, suffer from less social pressure than the animals of inferior status and, at the same time not have to exert energy in continual aggression to maintain its position as with the most

Ž .

dominant animals. This was also observed by Csermely and Wood-Gush 1990 , who noted that high-ranking sows spent more time defending the pile of food than actually feeding.

Ž .

Craig 1986 points out that when resources are limited, access is not gained in proportion to rank. Another possible cause for the most dominant animals not being the best producers is that when the animals are fed in the manger, the high-ranking animals

Ž .

tend to defend a particular area the center with a good supply of food while

subordinate animals quickly grab food at the edges and move only when forced to do so

ŽCsermely and Wood-Gush, 1986 . Similarly, Sherwin 1990 and Brouns and Edwards. Ž . Ž1994 obtained a significant negative correlation between rank in the hierarchy and.

priority access to limited feed; animals higher in the hierarchy were occupied with the strong defense of their individual space under the crowded conditions. Because of this, dominant goats spend time and energy in protecting their food supply such that their food intake is not always much greater than that of subordinates. Futhermore, Wierenga

Ž1990 pointed out that when animals eat at the feeding rack, they regularly change.

feeding places before all the food at the previous place has been consumed and that this kind of behavior is observed more often in high-ranking animals.

It must also be emphasized that, though there is no difference at birth in the weight of the suckling kids of higher and lower-ranking goats, there is a considerably higher weight increase in the suckling kids of top-ranking mothers. Upon birth, there is only a 300-g difference, but by the first month of life, the dominant mother’s suckling kids weigh 1700 g more than those of underlying mothers. The possible advantage of the dominant mother’s suckling kids over those of the lesser ranking mother’s would be, as

Ž . Ž .

pointed out by Espmark 1964 and Geist 1982 , that the offspring may benefit from their mother’s rank in terms of avoiding being displaced by other adults.

Ž .

Some authors have obtained similar results. Pretorius 1970 when working with flocks of goats of varying body weights found that the submissive, lighter animals lost an average of 8.3% body weight under conditions of a partially restricted feeding source. On the contrary, when the goats were regrouped into flocks of similar weight there was

Ž . Ž .

a progressive recovery of this deficit. Marincowitz 1968 and Pretorius 1970 report a direct relationship between social rank and mohair production.

5. Conclusions

influenced by the particularities of this flock, therefore it is necessary to be very prudent as for the generalizations that could be made. Nevertheless, the following seem clear in this flock.

Ø There is a clear dominance hierarchy that once established it remains stable in time.

Ø The animals with higher social rank are positively related to the aggressiveness, presence of horns, size and age.

Ø The dominant animals have a high-priority access to the food, both when feeding free in shepherding, and when taking the food supplement in the stall. Although the effect of this priority in the pasture is very reduced, in a limited space as the manger its effect is important. Because of it, the most important measure to avoid an increment of the aggressions during the food supplement would be to increase the number of mangers

Žstall to separate the individuals more..

Ø The animals of intermediate rank are the most productive, since neither are they so pressed as the subordinates, nor do they have to intervene constantly to maintain their status like the dominant ones. This effect would be limited, if the space for the individuals was increased both in the rest area of the animals, and in that of supplemen-tation.

References

Addison, W.E., Baker, E., 1982. Agonistic behavior and social organization in a herd of goats as affected by the introduction of non-members. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 8, 527–535.

Alados, C.L., 1983. Estudio de la direccionalidad en Gazella dorcas. In: XV Congreso Internacional de Fauna Cinegetica y Silvestre, Trujillo, Spain, pp. 405–420.´

Alados, C.L., 1986. Time distribution of activities in the Spanish ibex, Capra pyrenaica. Biol. Behav. 11, 70–82.

Alados, C.L., Escos, J., 1987. Relationships between movement rate, agonistic displacements and forage

Ž .

availability in Spanish ibexes Capra pyrenaica . Biol. Behav. 12, 245–255.

Alados, C.L., Escos, J., 1992. The determinants of social status and the effect of female rank on reproductive success in Dama and Cuvier’s gazelles. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 4, 151–164.

Alados, C.L., Escos, J., 1994. Social dominance and its correlates in the behaviour of captive Dama gazelle

ŽGazella dama . Mammalia..

Alcock, J., 1984. Animal behavior, an evolutionary approach. Sinauer Associates, MA. Alexander, R.D., 1974. The evolution of social behaviour. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 5, 325–384. Altmann, J., 1974. Observational study of behaviour: sampling methods. Behaviour 49, 227–267. Appleby, M.C., 1980. Social rank and food access in red deer stags. Behaviour 74, 294–308. Appleby, M.C., 1983. The probability of linearity in hierarchies. Anim. Behav. 31, 600–608. Arave, C.W., Albright, J.L., 1981. Cattle behavior. J. Dairy Sci. 64, 1318–1329.

Arnold, G.W., Dudzinski, M.L., 1978. In: Ethology of Free-Ranging Domestic Animals. Elsevier, Amsterdam, p. 197.

Arnold, G.W., Grassia, A., 1983. Social interactions amongst beef cows when competing for food. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 9, 239–252.

Barash, D.P., 1977. In: Sociobiology and Behaviour. Elsevier, New York, p. 378.

Barrette, C., Vandal, D., 1986. Social rank, dominance, antler size, and access to food in snow-bound wild woodland Caribou. Behaviour 97, 118–146.

Bartos, L., Perner, V., Losos, S., 1988. Red deer stags rank position, body weight and antler growth. Acta Theriol. 33, 209–217.

Beilharz, R.G., Mylrea, P.J., 1963. Social position and behaviour of dairy heifers in yards. Anim. Behav. 11, 522–528.

Beilharz, R.G., Butcher, D.F., Freeman, A.E., 1966. Social dominance and milk production in Holsteins. J. Dairy Sci. 49, 887–892.

Belovsky, G.E., 1984. Herbivore optimal foraging: a comparative test of three models. Am. Nat. 124, 97–115. Bennett, J.L., Finch, V.A., Holmes, C.R., 1985. Time spent in shade and its relationship with physiological

factors of thermoregulation in three breeds of cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 13, 227–236.

Ž .

Bernstein, I.S., 1970. Primate status hierarchies. In: Rosenblum, L.A. Ed. , Primate Behaviour 1 Academic Press, New York, pp. 71–109.

Bernstein, I.S., 1976. Dominance, aggression and reproduction in primate societies. J. Theor. Biol. 60, 459–472.

Bernstein, I.S., 1981. Dominance: the baby and the bathwater. Behav. Brain Sci. 3, 419–458. Bernstein, I.S., Sharpe, L.G., 1966. Social roles in a rhesus monkey group. Behaviour 26, 91–104. Bouissou, M.F., 1964. Observations sur la hierarchie sociale chez les Bovins domestiques. Diplome d’Etudes

Superieures, Faculte des Sciences, Paris.´ ´

Bouissou, M.F., 1970. Technique de mise en evidence des relations hierarchiques dans un group de bovins domestiques. Rev. Comp. Anim. 4, 66–69.

Bouissou, M.F., 1971. Effet de l’absence d’informations optiques et de contact physique sur la manifestation des relations hierarchiques chez les bovins domestiques. Ann. Biol. Anim., Biochem., Biophys. 11,´

191–198.

Bouissou, M.F., 1972. Influence of body weight and presence of horns on social rank in domestic cattle. Anim. Behav. 20, 474–477.

Bouissou, M.F., 1980. Social relationships in domestic cattle under modern management techniques. Boll. Zool. 47, 343–353.

Bouissou, M.F., 1981. Behaviour of domestic cattle under modern management techniques. In: Hood, D.E.,

Ž .

Tarrant, P.V. Eds. , The Problem of Dark Cutting in Beef. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Brakel, W.J., Leis, R.A., 1976. Impact of social disorganization on behavior, milk yield, and body weight of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 59, 716–721.

Brantas, G.C., 1968. On the dominance order in Friesian–Dutch dairy cows. Z. Tierz. Zuchtungsbiol. 84,¨

127–151.

Brouns, F., Edwards, S.A., 1994. Social rank and feeding behaviour of group-housed sows fed competitively or ad libitum. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 39, 225–235.

Brown, J.L., 1975. The Evolution of Behavior. Norton, New York.

Canali, E., Verga, M., Montagna, M., Baldi, A., 1986. Social interactions and induced behavioural reactions in milk-fed female calves. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 16, 207–215.

Candland, D.K., Bloomquist, D.W., 1965. Interspecies comparison of the reliability of dominance orders. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 59, 135–137.

Chase, I.D., 1985. The sequential analysis of aggressive acts during hierarchy formation: an application of the ‘‘jigsaw puzzle’’ approach. Anim. Behav. 33, 86–100.

Clutton-Brock, T.H., 1982. The functions of antlers. Behaviour 78, 108–125.

Clutton-Brock, T.H., Harvey, P.H., 1976. Evolutionary rules and primate societies. In: Bateson, P.P.G., Hinde,

Ž .

R.A. Eds. , Growing Points in Ethology. Cambridge University Press, pp. 195–237.

Clutton-Brock, T.H., Greenwood, P.J., Powell, R.P., 1976. Ranks and relationships in highland ponies and highland cows. Z. Tierpsychol. 41, 202–206.

Clutton-Brock, T.H., Guinness, F.E., Albon, S.D., 1982. The Red Deer: Evolution and Ecology of Two Sexes. Edinburgh University Press.

Collias, N.E., 1956. The analysis of socialization in sheep and goats. Ecology 37, 228–239.

Collis, K.A., 1976. An investigation of factors related to the dominance order of a herd of dairy cows of similar age and breed. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 2, 167–173.

Csermely, D., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1986. Agonistic behaviour in grouped sows: I. The influence of feeding. Biol. Behav. 11, 244–252.

Csermely, D., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1990. Agonistic behaviour in grouped sows II. How social rank affects feeding and drinking behaviour. Boll. Zool. 57, 55–58.

Dantzer, R., Mormede, P., 1979. Le stress en elevage intensif. Masson, Paris.´

Davies, W., 1925. The relative palatability of pasture plants. J. Minist. Agric. 32, 106. Deag, J.M., 1977. Aggression and submission in monkey societies. Anim. Behav. 25, 465–474.

Dickson, D.P., Barr, G.R., Wieckert, D.A., 1967. Social relationshipof dairy cows in a feed lot. Behaviour 29, 195–203.

Dittus, W.P.J., 1977. The social regulation of population density and age–sex distribution in the monkey. Behaviour 63, 281–322.

Eccles, T.R., Shackleton, D.M., 1986. Correlates and consequences of social status in female bighorn sheep. Anim. Behav. 34, 1392–1401.

Egerton, P.J.M., 1962. The cow–calf relationship and rutting behavior in American bison. Unpublished MS thesis, Univ. of Alberta.

Ekman, J.B., Askenmo, C.E.H., 1984. Social rank and habitat use in willow tit groups. Anim. Behav. 32, 508–514.

Emlen, J.M., 1973. Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach. Addison-Wesley, Reading.

Enoksson, B., 1988. Age- and sex-related differences in dominance and foraging behaviour of nuthatches

ŽSitta europaea . Anim. Behav. 36, 231–238..

Espmark, Y., 1964. Studies in dominance–subordination relation in a group of semi-domestic reindeer

ŽRangifer tarandus L. . Anim. Behav. 12, 420–425..

Ewbank, R., Meese, G.B., 1971. Aggressive behaviour in groups of domesticated pigs on removal and return of individuals. Anim. Prod. 13, 685–693.

Fraser, D., 1974. The behaviour of growing pigs during experimental social encounters. J. Agric. Sci. 82, 147–163.

Fraser, D., Rushen, J., 1987. Aggressive behavior. Vet. Clin. North Am.: Food Anim. Pract. 3, 285–305. Gauthereaux, S.A., 1978. The ecological significance of behavioural dominance. In: Bateson, P.P.G., Klopfer,

Ž .

P.H. Eds. , Perspectives in Ethology 3 Plenum, New York, pp. 17–54. Geist, V., 1966. The evolution of horn-like organs. Behaviour 27, 175–214.

Geist, V., 1971. Mountain Sheep: A Study in Behavior and Evolution. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Ž .

Geist, V., 1982. Adaptative behavioral strategies. In: Thomas, J., Towell, D.E. Eds. , The Elk of North America. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA, pp. 219–277.

Ž .

Hafez, E.S.E., Scott, J.P., 1962. The behaviour of sheep and goats. In: Hafez, E.S.E. Ed. , The Behaviour of Domestic Animals. Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, London.`

Ž .

Hall, M.J., 1983. Social organization in an enclosed group of red deer CerÕus elaphus L. on Rhum: I. The dominance hierarchy of females and their offspring. Z. Tierpsychol. 61, 250–262.

Hart, B.L., 1985. In: The Behavior of Domestic Animals. Freeman, New York, p. 390.

Hinde, R.A., 1978. Dominance and role — two concepts with dual meaning. J. Soc. Biol. Struct. 1, 27–38. Hinde, R.A., 1983. Primate Social Relationships: An Integrated Approach. Blackwell, Oxford.

Jones, M.G., 1933. Grassland management and its influence on the sward: IV. The management of poor pastures. V. Edaphic and biotic influences on pasture. Emp. J. Exp. Agric. 1, 361.

Kaufmann, J.H., 1967. Social relations of adult males in a free-ranging band of rhesus monkeys. In: Altmann,

Ž .

S.A. Ed. , Social Communication among Primates. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 73–98. Kaufmann, J.H., 1983. On the definition and functions of dominance and territoriality. Biol. Rev. 58, 1–20. Kelley, K.W., 1980. Stress and immune function: a bibliographic review. Ann. Rech. Vet. 11, 445–478. Kendall, M.C., 1962. Rank Correlation Methods. Charles Griffin, London.

Kiley-Worthington, M., 1978. The social organisation of a small captive group of eland, oryx and roan antelope with an analysis of personality profiles. Behaviour 66, 32–55.

Kilgour, R., Dalton, C., 1984. In: Livestock Behaviour, A Practical Guide. Granada Publishing, London, p. 319.

Kolb, E., 1971. Fisiologıa Veterinaria. Acribia, Zaragoza.´

Kucera, T.E., 1978. Social behavior and breeding system of the desert mule deer. J. Mammal. 59, 463–476.

Ž

Lamprecht, J., 1986. Structure and causation of the dominance hierarchy in a flock of bar-headed geese Anser

.

indicus . Behaviour 96, 28–48.

Ž .

Lee, P.C., 1983. Context-specific unpredictability in dominance interactions. In: Hinde, R.A. Ed. , Primate Social Relationships. Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 35–44.

Leuthold, W., 1977. African Ungulates: A Comparative Review of their Ethology and Behavioral Ecology. Springer, Berlın.´

Lincoln, G.A., 1972. The role of antlers in the behaviour of red deer. J. Exp. Zool. 185, 233–250.

Lincoln, G.A., Youngson, R.W., Short, R.V., 1970. The social and sexual behaviour of the red deer stag. J. Reprod. Fertil. 11, 71–103.

Locati, M., Lovari, S., 1991. Clues for dominance in female chamois: age, weight, or horn size? Aggressive Behavior 17, 11–15.

Lott, D.F., 1979. Dominance relations and breeding rate in mature male American bison. Z. Tierpsychol. 49, 418–432.

Lott, D.F., Galland, J.C., 1987. Body mass as a factor influencing dominance status in American bison cows. J. Mammal. 68, 683–685.

Lynch, J.J., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., Davies, H.I., 1985. Aggression and nearest neighbours in a flock of Scottish blackface ewes. Biol. Behav. 10, 215–225.

MacArthur, R.H., Pianka, E.R., 1966. On optimal use of a partchy environment. Am. Nat. 100, 603–609. Marincowitz, G., 1968. Effect of an order of dominance on production and reproduction in angora goat.

Angora Goat Mohair J. 10, 25–26.

Ž .

McHugh, T., 1958. Social behavior of the American buffalo Bison bison bison . Zoologica 43, 1–40.

Ž .

Metz, J.H.M., 1983. Food competition in cattle. In: Baxter, S.H., Baxter, M.R., MacCormack, J.A.C. Eds. , Farm Animal Housing and Welfare. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Owen-Smith, N., Novellie, P., 1982. What should a clever ungulate eat? Am. Nat. 119, 151–178.

Ozaga, J.J., 1972. Aggressive behavior of white-tailed deer at winter cuttings. J. Wildl. Manage. 36, 861–868. Orgeur, P., Mimouni, P., Signoret, J.P., 1990. The influence of rearing conditions on the social relationships of

Ž .

young male goats Capra hircus . Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 27, 105–113.

Ž

Pretorius, P.S., 1970. Effect of aggressive behaviour on production and reproduction in the angora goat Capra

.

hircus angoraensis . Agroanimalia 2, 161–164.

Pyke, G.H., Pulliam, H.R., Charnov, E.L., 1977. Optimal foraging: a selective review of theory and tests. Q. Rev. Biol. 52, 137–154.

Reinhardt, V., 1980. Untersuchung zum Socialverhalten des Rindes. Birkauser, Basel, 89 pp.¨

Reinhardt, V., 1985. Social behaviour in a confined bison herd. Behaviour 92, 209–226. Reinhardt, V., Flood, P.F., 1983. Behavioural assessment in muskox calves. Behaviour 87, 1–21.

Reinhardt, V., Reinhardt, A., 1975. Dynamics of social hierarchy in a dairy herd. Z. Tierpsychol. 38, 315–323. Reinhardt, V., Reinhardt, A., Reinhardt, C., 1987. Evaluating sex differences in aggressiveness in cattle, bison

and rhesus monkeys. Behaviour 102, 58–66. Ross, O., 1960. Swine housing. Agric. Eng. 41, 584–585.

Ross, S., Scott, J.P., 1949. Relationships between dominance and control of movement in goats. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 42, 75–80.

Rowell, T.E., 1966. Hierarchy in the orgazization of a captive baboon group. Anim. Behav. 14, 430–433. Rowell, T.E., 1974. The concept of social dominance. Behav. Biol. 11, 131–154.

Rutberg, A.T., 1986. Dominance and its fitness consequences in american bison cows. Behaviour 96, 62–91. Schaller, G.B., 1977. Mountain Monarchs. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Schein, M.W., Forhman, M.H., 1955. On social dominance relationships in a herd of dairy cattle. Br. J. Anim. Behav. 3, 45–55.

Schoener, T.W., 1971. Theory of feeding strategies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2, 369–404.

Ž

Scott, D.K., 1980. Functional aspects of the pair bond in winter in Bewick’s swans Cygnus columbianus

.

bewickii . Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 7, 323–327.

Scott, J.P., 1948. Dominance and the frustration–aggression hypothesis. Physiol. Zool. 21, 31–39.

Ž .

Shank, C.C., 1972. Some aspects of social behaviour in a population on feral goats Capra hircus L. . Z. Tierpsychol. 30, 488–528.

Sherwin, C.M., 1990. Priority of access to limited feed, butting hierarchy and movement order in a large group of sheep. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 25, 9–24.

Sherwin, C.M., Jhonson, K.G., 1987. The influence of social factors on the use of shade by sheep. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 18, 143–155.

Shopland, J.M., 1987. Food quality, spatial deployment, and the intensity of feeding interference in yellow

Ž .

baboons Papio cynocephalus . Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 21, 149–156. Siegel, H.S., 1980. Physiological stress in birds. Bioscience 30, 529–534.

Sokal, R.R., Rohlf, F.J., 1969. Biometry. The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research. Freeman, San Francisco.

Stapledon, R.G., 1934. Palatability and management of the poorer grass lands. J. Minist. Agric. 41, 321. Stewart, J.C., Scott, J.P., 1947. Lack of correlation between leadership and dominance relationships in a herd

of goats. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 40, 255–264.

Stricklin, W.R., Graves, H.B., Wilson, L.L., Singh, R.K., 1980. Social organization among young beef cattle in confinement. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 6, 211–219.

Ž .

Struhsaker, T.T., 1967. Behaviour of vervet monkeys Cercopithecus aethiops . Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 82, 1–64.

Syme, G.J., 1974. Competitive orders as measures of social dominance. Anim. Behav. 22, 931–940. Syme, G.J., Syme, L.A., 1979. In: Social Structure in Farm Animals. Elsevier, Amsterdam, p. 200. Syme, L.A., Syme, G.J., Pearson, A.J., 1975. Spatial distribution and social status in a small herd of dairy

cows. Anim. Behav. 23, 609–614.

Thouless, C.R., 1990. Feeding competition between grazing red deer hinds. Anim. Behav. 40, 105–111. Thouless, C.R., Guinness, F.E., 1986. Conflict between red deer hinds: the winner always wins. Anim. Behav.

34, 1166–1171.

Townsend, T.W., Bailey, E.D., 1981. Effects of age, sex and weight on social rank in penned white-tailed deer. Am. Midl. Nat. 106, 92–101.

Tyler, S.J., 1972. The behaviour and social organization of the New Forest ponies. Anim. Behav. Monogr. 5, 87–196.

Vivas, H.J., Saether, B.E., 1987. Interactions between a generalist herbivore, the moose Alces alces, and its food resources: an experimental study of winter foraging behaviour in relation to browse availability. J. Anim. Ecol. 56, 509–520.

Warrick, G.D., Krausman, P.R., 1987. Foraging behavior of female mountain sheep in western Arizona. J. Widl. Manage. 51, 99–104.

Wierenga, H.K., 1984. The social behaviour of dairy cows: some differences between pasture and cubicle

Ž .

system. In: Unshelm, J., VanPutten, G., Zeeb, K. Eds. , Proceedings of the International Congress on Applied Ethology in Farm Animals, Darmstadt, KBTL, Kiel.

Wierenga, H.K., 1990. Social dominance in dairy cattle and the influences of housing and management. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 27, 201–229.