Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:12

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Experiencing and Measuring the Unteachable:

Achieving AACSB Learning Assurance

Requirements in Business Ethics

Katherine E. Lawrence , Kendra L. Reed & William Locander

To cite this article: Katherine E. Lawrence , Kendra L. Reed & William Locander (2011)

Experiencing and Measuring the Unteachable: Achieving AACSB Learning Assurance Requirements in Business Ethics, Journal of Education for Business, 86:2, 92-99, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.480991

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.480991

Published online: 23 Dec 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 119

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.480991

Experiencing and Measuring the Unteachable:

Achieving AACSB Learning Assurance

Requirements in Business Ethics

Katherine E. Lawrence, Kendra L. Reed, and William Locander

Loyola University of New Orleans, New Orleans, Louisiana, USAThe AACSB requires continuous improvement of business school outcomes through a com-prehensive Assurance of Learning program. Measuring ethical decision making poses an interesting challenge for schools making it central to their mission. The authors provide an innovative and effective approach to assessing ethical decision making and closing the loop for continual improvement. Using a web-based simulation, results from 2 cohorts suggest that improvements based on shortcomings of one cohort can impact decision-making behaviors of subsequent cohorts.

Keywords:AACSB, assurance of learning, business ethics, education, ethical decision making, web-based simulation

The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) requirements for accreditation command business schools to implement an Assurance of Learning (AoL) pro-gram that assesses the extent to which curricula achieve edu-cational missions. AoL programs provide answers to critical questions such as, “What should our graduates be able to do?” and “What improvements can be made to increase acquisi-tion of these skills?” The AACSB (2007) places mounting pressure on business schools by stating that they “should be demonstrating a high degree of maturity in terms of outcome assessment processes, demonstrated use of outcome assess-ment processes, and demonstrated use of assessassess-ment infor-mation to improve curricula” (p. 69). To the business school struggling to maintain AACSB-accredited status or seeking accreditation for the first time, the task appears daunting and expensive. Martell (2007) reported that 80% of business schools spent financial resources on both training and faculty stipends in 2006 and 43% spent resources on instruments for measuring learning goals. In addition to the resource burden, substantive qualitative concerns exist. Martell found that over half of the schools surveyed worried about the time require-ments, faculty involvement and knowledge, and closing the loop for continual improvement.

Correspondence should be addressed to Katherine E. Lawrence, Loyola University of New Orleans, College of Business, 6363 St. Charles Avenue, Box 15, New Orleans, LA 70118, USA. E-mail: kelawren@loyno.edu

Today’s competitive educational environment requires as-sessment for effective improvement of learning. This chal-lenges schools featuring softer skills, such as ethical decision making (EDM) in their mission. These less tangible skills of-ten require more innovation, time, effort, and dollars than, for example, accounting and financial skills, which can be as-sessed with more traditional techniques (e.g., multiple-choice tests). Assessment of EDM presents its own ethical conun-drum when a mission statement claims to prepare graduates with ethical decision-making skills and the AoL program must capture this elusive goal. The temptation is to exclude intangible learning goals from the AoL, but this can lead to loss of accreditation. Thus, faculty must be innovative in developing processes and measures of the softer, mission-related skills.

This article proposes an effective and efficient approach to assessing the intangible skill of EDM. Examples of the im-pact of unethical decision making are rampant in the present business environment. For example, high-profile ethical dis-asters such as Enron and WorldCom have caused widespread adversity to innocent people. TheWashington Postprovided another example in which it promoted salons in the chief editor’s home under conditions deemed as conflicts of in-terest between media, industry sponsors of the salons, and politicians (Alexander, 2009). The details demonstrated a lack of ethical leadership in the organization; members along the decision-making chain claimed to believe that someone else was attending to the ethical implications of the salons.

MEASURING THE UNTEACHABLE 93

Leadership put tenuous promises of revenue ahead of jour-nalistic integrity. Clearly, business curricula must provide students with better tools for EDM to prepare them for supe-rior leadership (Koehn, 2005).

With respect to EDM, most business ethics textbooks introduce and apply classic philosophies of ethical tradi-tions to business situatradi-tions. Innovative web-based simu-lations similarly apply these philosophies, but they more readily provide feedback on the impact of decisions based on the different philosophies (e.g., The EthicsGame [www.ethicsgame.com]). One advantage of such simulations is the automatic recording and tracking of decision choices and their impact. These data become readily available to the instructor for analysis and subsequent pedagogical improve-ments.

The AACSB (2007) holds that business schools must demonstrate continual improvement of student learning by showing that students are meeting standards on learning goals reflected in the schools’ missions. Presently, AACSB re-quirements do not call for inferential statistical techniques. Instead, demonstrating that a targeted percentage graduates meets standards is confirmation enough, provided that there is a trend of continuous improvement over time. However, most academics expect a robust methodology. The approach de-scribed in this paper utilizes a chi-square test of differences to compare two consecutive cohorts on the EDM learning goal, using computer-generated data from a simulation called The EthicsGame. The game is advocated here as an example only; other simulations or assignments developed by an instructor can be readily applied to the systematic approach described. The pedagogical changes applied to the second cohort fo-cus on the areas in which the first cohort performed poorly. The results uncovered patterns of behavior that provided in-sights into students’ EDM abilities and provided inspiration for further research into the drivers of student learning and the consequences of pedagogical improvement.

Taking on the difficulty of assessing the unteachable (or the unassessable) and sharing the results with others can inspire credibility of educational programs while preserving a love of teaching and learning. To contribute toward the resolution of this challenge, we (a) review the literature on business ethics education, (b) describe a simple framework for AoL assessment, (c) provide a specific assessment plan for EDM, and (d) offer empirical support of this approach.

Literature Review

A review of present literature suggests EDM begs for im-provements that can demonstrate impact on ethical reason-ing and choices. Empirical research suggests that at the un-dergraduate level, business majors are no less ethical than are liberal arts majors (Klein, Levenburg, McKendall, & Mothersell, 2007). Undergraduate students of all majors have essentially equivalent ethical reasoning abilities (Herington & Weaven, 2002). Research on MBA students suggests

that the length of time spent in an academic program re-lates negatively to an individual’s ethical nature (Gundersen, Capozzoli, & Rajamma, 2008). A two-year stint in an MBA program can increase individuals’ self-centered val-ues and decrease their valval-ues dealing with concern for others (Krishnan, 2007). These findings suggest that the impact of education on ethics and reasoning abilities warrants further investigation.

Effective approaches to EDM education should provide students with both a clear objective and standardized ap-proach to ethical reasoning. Waples, Antes, Murphy, Con-nelly, and Mumford (2009) performed a meta-analysis of business ethics education research that clearly uncovered different ethics programs aim for different outcomes. Some programs aim for students’ increased awareness of ethical problems (Wynd & Mager, 1989). Other educators strive to teach classic moral philosophies, and still others concentrate on moral reasoning processes, decision choices, and behav-iors (Ho, Vitell, Barnes, & Desborde, 1997). Waples et al. found that ethics instruction has minimal reportable effect on the basic aspects of ethical reasoning and decision making. Goolsby and Hunt (1992) and Ho et al. found that indi-viduals are more likely to make good ethical decisions when they can utilize a systematic reasoning process. The optimum learning conditions for ethics education include teaching stu-dents ethical philosophies in a required ethics class and then integrating the theories into ethical problems presented in subsequent business classes (Ritter, 2006).

We propose one approach to teaching EDM based on clear objectives, systematic approach, and efficient link to AoL data collection, assessment, and improvement initiatives.

Ethical Decision-Making Simulation

Similar to many standard procedures for teaching EDM in textbooks, the web-based simulation software The Ethics-Game follows a four-stage process for EDM in solving eth-ical problems in a corporation: (a) situation assessment, (b) alternative evaluation, (c) choice of action, and (d) reflection. Similar to other pedagogical approaches, the game teaches students to apply classic ethical traditions (e.g., Kant’s cate-gorical imperative) in combination with systematic reasoning process to arrive at sound decisions.

First, students read a short case situation and identify the ethical actor (i.e., themselves), stakeholders (e.g., employees, customers, community), context, and ethical issue. Students must articulate the problem in ethical terms (i.e., how the problem affects multiple stakeholders) rather than technical terms.

Second, students execute a guided procedure that an-alyzes 3–4 potential choices for action. The choices are analyzed through one (of four) ethical traditions (one tradition per scenario). Because the ethical philosophies are commonly found in business ethics textbooks, the AoL guidelines described in this article can be applied to various

classroom exercises. The four ethical traditions are described subsequently (adapted from Baird, 2005). The pros and cons of each perspective are discussed in class.

1. Rights and responsibilities. An ethical action is de-fined by doing one’s duty for all stakeholders. Kant (2002), exemplifying this tradition, said that through reason individuals can discover universal principles upon which they must act even if doing so is uncom-fortable. The instructor points out that although some scholars find this perspective to be a useful guide for business behavior (see Borowski, 1998), other authors have questioned that the maxims have too many con-tingencies to be of practical use (see Bruton 2004). In agreement with the skeptics, often at least one stu-dent presents the cynical argument that everyone cheats and deceives in business and to be in business implies the consent to be cheated and deceived; therefore, in cheating and deceiving others individuals are treating people according to the Golden Rule. In this case, the instructor directs the students toward the duty and re-sponsibilities imperative.

2. Utilitarianism. An ethical action provides the most happiness to the greatest amount of people. Exempli-fied by Mill (2003), this tradition is rooted in teleology, asking students to provide the best outcomes for the most stakeholders. Students are generally comfortable with business as a means of creating overall good in a society as each individual “necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of society as great as he can (Mill, 1876/2003, p. 184). Classroom discussion brings up counterarguments, such as those presented by Ladkin (2006), who argued that utilitarianism (and deontology) fail to account for the contextual and con-tingent nature of the business climate.

3. Justice theory. An ethical action is one that sustains a just environment. The archetypical justice theorist, Rawls (1971), says that people should make choices from the vantage of the least advantaged to create and sustain a healthy society that levels the playing field. In the game, students first identity the basic liberties entitled to all stakeholders. Interestingly, students’ re-actions to Rawls mirror those found in business ethics literature. On one hand, some theorists contend that justice theories are appropriate for business decisions because the aim of business organizations and the laws that contain them should be to ensure the de-velopment of a just society (see Marens, 2007.) On the other hand, other scholars such as Phillips and Margolis (1999) contended that justice theory is un-suitable for business because such politicized theories are designed for the state, which are different entities from organizations.

4. Virtue ethics.An ethical action is one that reflects the virtues of integrity, compassion, and courage. Rather

than prescribing formulaic rules, virtue ethics grounds decisions on building and maintaining good charac-ter. MacIntyre (1984) exemplified this ethical tradi-tion, stating that an individual’s sense of core im-mutable values become salient as character traits and drivers of action, and thus ethical relativism is miti-gated. The instructor introduces theory and research pertaining to virtue ethics in business (e.g., Bertland, 2009). For instance, empirical research has found that virtue ethics can be operationalized, integrated into management models, and utilized to teach students about making moral judgments in business (Dyck & Kleysen, 2001). Students are particularly attracted to Solomon (1993), who argued that Aristotelian virtue ethics is appropriate for business because of its emphasis on the personal development of virtues such as honesty, loyalty, trustworthiness, courage, and compassion.

Once students perform a systematic consideration of be-havior choices, the third step requires they choose an option that is MOST consistent with the ethical framework being studied. Illegal options are not considered in the game. Stu-dents communicate their decision in a memo addressed to team members.

Fourth, students write a reflection piece on personal bias, emotions, and hubris that might have swayed their decisions. This step is regarded as a critical moment in EDM; there-fore, students are evaluated on their ability to self-reflect. The EthicsGame and the AoL guidelines distinguish be-tween (a) the ability to choose the option consistent with an ethical tradition and (b) the ability to reflect on how well the tradition fits individuals’ personal beliefs. The combi-nation of skills should guide a person toward better EDM ability.

Ramsay (2007) warned that using a variety of ethical philosophies that lead to different conclusions may lead stu-dents toward indecisiveness and moral skepticism about any ethical principle, which defeats the purpose of ethics educa-tion. To circumvent this potential downside, we stress that EDM demands taking a stand on decision and action. In other words, in the context of business education, we strive to educate future leaders about the EDM process so that they can utilize it when making necessary decisions and taking responsible action.

METHOD

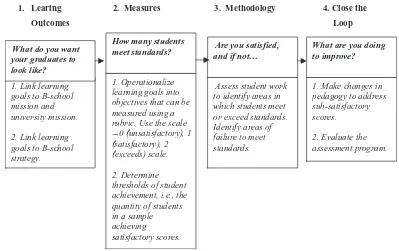

To improve student learning, we designed and utilize an AoL program following the four-phase process shown in Figure 1. The four phases are (a) determine mission-driven learning outcomes, (b) operationalize and measure outcomes, (c) analyze results, and (d) close the loop.

MEASURING THE UNTEACHABLE 95

meet standards? Are you satisfied, and if not… What are you doing to improve?

1. Operationalize learning goals into objectives that can be measured using a rubric. Use the scale -0 (unsatisfactory), 1

Assess student work to identify areas in which students meet or exceed standards. Identify areas of

FIGURE 1 Four-phase approach to assurance of learning.

Phase 1—Determine Mission-Driven Learning Outcomes

The first phase answers the question, “What do we want our graduates to be able to do?” The answer becomes the learning objective. It must be aligned with the university’s and business school’s mission and strategic plan. Thus, this is a two-step process: (a) learning goals to mission and (b) link learning goals to strategy.

Step 1—Link learning goals to mission. The link be-tween the mission statement and learning goals outlined in the AoL cannot be overstated. At our school, a Jesuit Uni-versity, Ignatian spirituality drives the mission and vision. Within this framework, a team of faculty members devel-oped the following learning goal: “graduates will be able to make ethical decisions in business contexts.” The EDM re-lates to the published university mission: “[our university]. . .

prepares them to lead meaningful lives with and for others; to pursue truth, wisdom, and virtue; and to work for a more just world.” Next, the team refined the EDM learning goal into three objectives. Specifically, graduates will be able to (a) identify ethical business issues, (b) apply a sound procedure for arriving at ethical decisions, and (c) understand and have the capacity for critical self-reflection.

Step 2—Link learning goals to strategy. The learn-ing goals cannot exist in isolation but instead must be in-tegrated into the college’s strategic plans. For example, our business school sponsors a Center for Ethics in Business, a Center for Spiritual Capital, and purchases The EthicsGame

licenses. Moreover, our Freshmen Year Experience Program includes lectures, guest lectures, and readings on ethics and social responsibilities of business.

Phase 2—Operationalize and Measure Outcomes

The second phase involves the development of measures for assessing the learning goals. When committed to building competencies in softer skills, such as EDM, this phase elic-its inherent challenges. However, the data provided by the simulation enabled us to more easily take an already existing course activity and translate the data to a usable format in AoL assessment. This process requires two steps: (a) opera-tionalizing goals with a rubric and (b) determining achieve-ment goal levels.

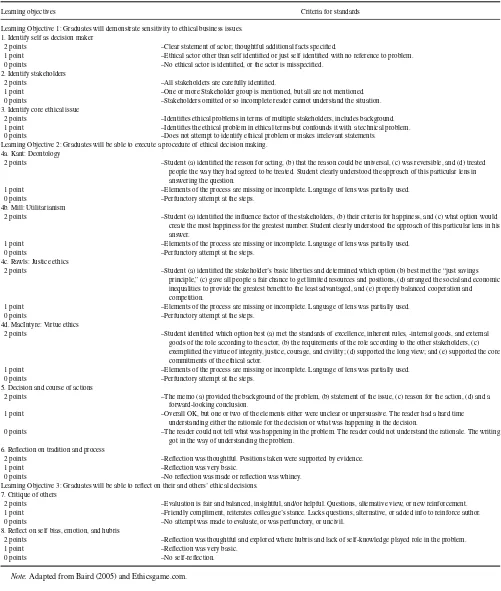

Step 1—Operationalize goals with a rubric. The learning goals must be operationalized so that they can be measured and analyzed. When dealing with nonquan-titative competencies, the rubric method championed by AACSB serves this purpose. We developed an 8-item rubric based on the ethical reasoning process and mea-surement tools provided by The EthicsGame. In accor-dance with AACSB requirements, each item is measured on a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not meet-ing standards) to 2 (exceeding standards). In developing criteria for each point of the scales, we strove to elimi-nate ambiguity so that anyone familiar with the objectives and assignment could discern between the three levels of competency. By transforming the EDM learning goal into

eight tangible items, we learned that if a learning goal appears too abstract for measurement, then we unpack it into measureable pieces.

Step 2—Determine student achievement levels.

The next step is to define college-level standards of achieve-ment aligned with AACSB requireachieve-ments. Because the AACSB allows schools to choose their own targets of suc-cess (within reason), we aimed for at least 80% of our student sample meeting or exceeding standards for each of the eight items. If less than 80% of the student sample failed to meet standards on an item, then pedagogical or curriculum changes were to be made and the next group of students would be as-sessed in the subsequent semester. This is closing the loop (discussed in Phase 4).

Phase 3—Collect and Analyze Data

By collecting and assessing student results using the rubric, faculty can identify areas in which students meet standards and those areas that need improvement. In our study, two consecutive semesters of a marketing course comprised the sample: Cohort 1 (n=37) and Cohort 2 (n=25). After the four rounds of the EDM simulation, the instructor evaluated the work of Cohort 1 against the rubric (Table 1). Results were tallied to show how many students met, surpassed, or failed to meet the eight standards. Based on the results, the instructor made pedagogical changes in the same class during the following semester with intentions on improving learning outcomes.

RESULTS

Chi-Square Results

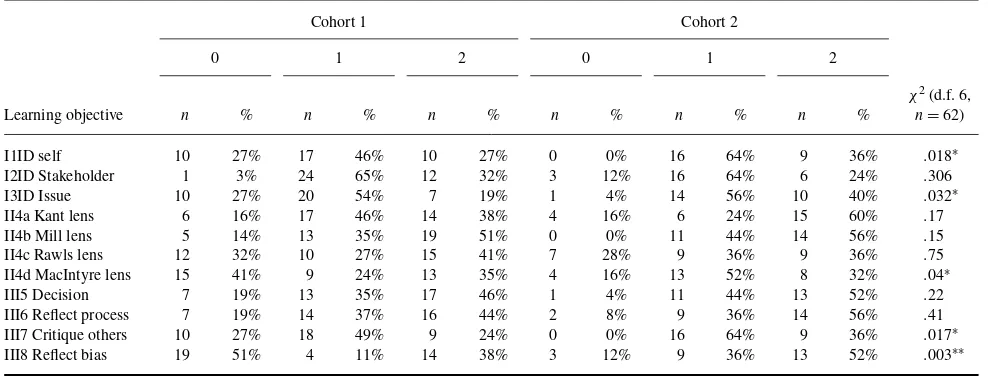

In this section, we discuss both the results of the chi-square test and, critically dependent on these results, the fourth and final phase of the AoL program: close the loop.

Table 2 presents the results of Cohorts 1 and 2 organized according to the learning objectives and the three levels of learning. The last column lists the results of the chi-square tests. In cases in which the chi square is significant, the improvement in number of students who meet or exceed the standard is statistically noteworthy. For example, in the first learning objective, item 1 asks students to pinpoint the self as decision maker. Only 73% of Cohort 1 met or ex-ceeded the standard for this item; this did not meet the 80% or above standard. However, in the first learning objective, item 2, 97% correctly identified at least three stakeholders. Thus, although students seemed capable of imagining who might be affected by a problem, they struggled with recog-nizing that they hold the locus of responsibility to an ethical challenge.

Chi-square tests of differences were performed on the scores for all eight learning objectives of the two cohorts.

Ad-ditional chi-square tests were performed to explore whether gender, class standing (i.e., junior or senior), major, and prior completion of the required business ethics course had an ef-fect on the differences beyond the efef-fects of cohort mem-bership. Gender and class standing were analyzed because prior research suggested that these factors influence ethical development (Borkowski & Ugras, 1998). Chi-square tests of differences revealed no significant differences between gen-der or class year. Because the sample size of groups by major were too small for comparison (i.e., accounting, finance, and all others totaled 3 students), we compared marketing majors (n=27) to all other business majors (n=35). The only sig-nificant difference that emerged was that in the utilitarianism item the marketing majors scored statistically significantly higher than did the other majors, χ2 (d.f. 6, n = 62) =

0.019. Finally, we also explored potential effects of taking the formally required business ethics course. We reasoned that repeated exposure to ethics education, which intended to improve cognitive moral development, would lead to better ethical judgments (Goolsby & Hunt, 1992; Ho et al., 1997). Chi-square, χ2(d.f. 6,n=62)=0.005, results suggested

that, as desired, students who had taken the required business ethics course performed better than did the other students.

Phase 4—Close the Loop

The assessment findings must be acted on for the AoL pro-gram to add value toward improved learning and thus close the loop. The fourth phase of the assessment program re-quired two steps: (a) implement new pedagogy to increase learning and (b) evaluate the AoL for effectiveness.

Step 1—Implement new pedagogy. This segment of an AoL program is both humbling and challenging to faculty, but it is also the most rewarding when improvements to stu-dent learning are the outcome. From the results of Cohort 1, we isolated the following strategies for implementation with Cohort 2 semester in attempts to close the learning loop for EDM.

For the first learning objective (focus on students taking ownership of ethical decision making, especially in the areas of identifying the self as decision maker and self reflection on personal bias and hubris), we felt that the reluctance to identify the self as decision maker and reluctance to reflect on the self indicated an overarching problem with ownership of EDM. If individuals thought more deeply about their per-sonal biases and hubris, then they might better understand and be able to overcome their own hesitations about making decisions. Therefore, we (a) introduced practice runs into the classroom activity that simulate the game, (b) brought in guest speakers and offered stories from personal experience about hard ethical decisions, and (c) introduced additional real-world instances of ethical lapses. To encourage personal reflection, emphasis on class discussions was expanded. Con-versations drove home the notion that ethical problems are

MEASURING THE UNTEACHABLE 97

TABLE 1

Rubric for Ethical Decision-Making Learning Objectives in Business Marketing

Learning objectives Criteria for standards

Learning Objective 1: Graduates will demonstrate sensitivity to ethical business issues. 1. Identify self as decision maker

2 points –Clear statement of actor; thoughtful additional facts specified.

1 point –Ethical actor other than self identified or just self identified with no reference to problem. 0 points –No ethical actor is identified, or the actor is misspecified.

2. Identify stakeholders

2 points –All stakeholders are carefully identified.

1 point –One or more Stakeholder group is mentioned, but all are not mentioned. 0 points –Stakeholders omitted or so incomplete reader cannot understand the situation. 3. Identify core ethical issue

2 points –Identifies ethical problems in terms of multiple stakeholders, includes background. 1 point –Identifies the ethical problem in ethical terms but confounds it with a technical problem. 0 points –Does not attempt to identify ethical problem or makes irrelevant statements.

Learning Objective 2: Graduates will be able to execute a procedure of ethical decision making. 4a. Kant: Deontology

2 points –Student (a) identified the reason for acting, (b) that the reason could be universal, (c) was reversible, and (d) treated people the way they had agreed to be treated. Student clearly understood the approach of this particular lens in answering the question.

1 point –Elements of the process are missing or incomplete. Language of lens was partially used.

0 points –Perfunctory attempt at the steps.

4b. Mill: Utilitarianism

2 points –Student (a) identified the influence factor of the stakeholders, (b) their criteria for happiness, and (c) what option would create the most happiness for the greatest number. Student clearly understood the approach of this particular lens in his answer.

1 point –Elements of the process are missing or incomplete. Language of lens was partially used.

0 points –Perfunctory attempt at the steps.

4c. Rawls: Justice ethics

2 points –Student (a) identified the stakeholder’s basic liberties and determined which option (b) best met the “just savings principle,” (c) gave all people a fair chance to get limited resources and positions, (d) arranged the social and economic inequalities to provide the greatest benefit to the least advantaged, and (e) properly balanced cooperation and competition.

1 point –Elements of the process are missing or incomplete. Language of lens was partially used.

0 points –Perfunctory attempt at the steps.

4d. MacIntyre: Virtue ethics

2 points –Student identified which option best (a) met the standards of excellence, inherent rules, -internal goods, and external goods of the role according to the actor, (b) the requirements of the role according to the other stakeholders, (c) exemplified the virtue of integrity, justice, courage, and civility; (d) supported the long view; and (e) supported the core commitments of the ethical actor.

1 point –Elements of the process are missing or incomplete. Language of lens was partially used.

0 points –Perfunctory attempt at the steps.

5. Decision and course of actions

2 points –The memo (a) provided the background of the problem, (b) statement of the issue, (c) reason for the action, (d) and a forward-looking conclusion.

1 point –Overall OK, but one or two of the elements either were unclear or unpersuasive. The reader had a hard time understanding either the rationale for the decision or what was happening in the decision.

0 points –The reader could not tell what was happening in the problem. The reader could not understand the rationale. The writing got in the way of understanding the problem.

6. Reflection on tradition and process

2 points –Reflection was thoughtful. Positions taken were supported by evidence.

1 point –Reflection was very basic.

0 points –No reflection was made or reflection was whiney. Learning Objective 3: Graduates will be able to reflect on their and others’ ethical decisions.

7. Critique of others

2 points –Evaluation is fair and balanced, insightful, and/or helpful. Questions, alternative view, or new reinforcement. 1 point –Friendly compliment, reiterates colleague’s stance. Lacks questions, alternative, or added info to reinforce author. 0 points –No attempt was made to evaluate, or was perfunctory, or uncivil.

8. Reflect on self bias, emotion, and hubris

2 points –Reflection was thoughtful and explored where hubris and lack of self-knowledge played role in the problem.

1 point –Reflection was very basic.

0 points –No self-reflection.

Note.Adapted from Baird (2005) and Ethicsgame.com.

TABLE 2

Learning Objectives Scores, by Cohort

Cohort 1 Cohort 2

0 1 2 0 1 2

Learning objective n % n % n % n % n % n %

χ2(d.f. 6,

n=62)

I1ID self 10 27% 17 46% 10 27% 0 0% 16 64% 9 36% .018∗

I2ID Stakeholder 1 3% 24 65% 12 32% 3 12% 16 64% 6 24% .306

I3ID Issue 10 27% 20 54% 7 19% 1 4% 14 56% 10 40% .032∗

II4a Kant lens 6 16% 17 46% 14 38% 4 16% 6 24% 15 60% .17

II4b Mill lens 5 14% 13 35% 19 51% 0 0% 11 44% 14 56% .15

II4c Rawls lens 12 32% 10 27% 15 41% 7 28% 9 36% 9 36% .75

II4d MacIntyre lens 15 41% 9 24% 13 35% 4 16% 13 52% 8 32% .04∗

III5 Decision 7 19% 13 35% 17 46% 1 4% 11 44% 13 52% .22

III6 Reflect process 7 19% 14 37% 16 44% 2 8% 9 36% 14 56% .41

III7 Critique others 10 27% 18 49% 9 24% 0 0% 16 64% 9 36% .017∗

III8 Reflect bias 19 51% 4 11% 14 38% 3 12% 9 36% 13 52% .003∗∗

∗

α=.05.,∗∗α=.01.

more varied and subtle than law or codes portend, and some-times ordinary people are called to make heroic choices.

For the second learning objective (develop in-class as-signments that introduce selected concepts from justice theory and virtue ethics), justice theory and virtue ethics were more challenging to students than were the rights and responsibilities and utilitarian perspectives. Therefore, we developed small-scale in-class assignments applying con-cepts from these traditions to an existing video case study dealing with small business activity in Cuba. The video de-scribes attempts Cubans make with small business ventures to alleviate gross poverty. Not only does this help students see beyond ideology (i.e., communism vs. capitalism), but also it shows how business activity can enact social jus-tice. The virtues ethics approach was also highlighted in a new course unit based on C. K. Prahalad’s (2004) book,The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits. Here, students learned about a virtuous and courageous approach to international business and market-ing through cooperation among businesses, consumers, en-trepreneurs, governments, and NGOs. These alterations to pedagogy have no direct relationship to the game, but in-stead provide business contexts for applying the concepts from justice theory and virtue ethics.

Step 2—Evaluate the assessment program. This final step involved evaluating the assessment program to de-termine if it actually improved student learning over time. One common mistake is to micromanage the data collection process so that emphasis is placed on collecting data and not on using data and taking action. Therefore, this step in-volves a reality check. We did this informally by trusting faculty members who were relatively less involved in EDM assessment to make suggestions for improving the assess-ment process. For example, we received feedback that that

the grading scale might be too lenient. Therefore, preceding the next round of assessment, the next person who assessed EDM was trained to apply the rubric more rigorously.

DISCUSSION

Assessment Process and Empirical Results

We proposed a plan for streamlining learning assessment to manage financial costs, encourage faculty involvement, and foster closing the loop for continuous improvement of the learning goal EDM. We subjected our results to a series of simple chi-square tests that suggested that some relationship exists between increased student learning of EDM and adap-tations made to classroom pedagogy. Student performance seemed to improve from one semester to the next when the instructor made pedagogical changes based on the AoL assessment data. This finding is supported by the fact that student learning was improved on the dimensions to which attention was directed. The additional analyses of potential explanatory factors that influence EDM also provided in-teresting results. Consistent with prior research, we found no differences between demographic groups such as gen-der or class year. All of the majors performed equally, with the exception of marketing students appearing to perform slightly higher on the utilitarianism perspective. More inter-esting and relevant to ethics education was the finding that students with exposure to a required business ethics course were more adept at reflecting on the overall ethical reason-ing process. These findreason-ings suggest that exposure to multiple ethical instruction formats may prepare students for EDM. Consistent with AACSB, we assert that the AoL program should efficiently increase the number of students graduat-ing with the desired capabilities, and therefore, should yield information that can be readily interpreted and acted on by

MEASURING THE UNTEACHABLE 99

instructors. The turnaround time for gathering, analyzing, disseminating, and acting on the information must be quick. Our program demonstrates the ability to assess aspects of EDM and interpret results in one semester and then imple-ment effective changes and assess their impact in the follow-ing semester. This closes the loop within one academic year efficiently and without excessive burden on the instructor.

Limitations

Although the results support a positive impact of ethics instruction on learning, limitations of the study must be acknowledged. First, the results from the chi-square tests of small sample sizes (determined by enrollment) must be viewed with caution. Larger sample sizes should be used to have the power to use more advanced analytical techniques. Moreover, we used a single data analyzer rather than multiple judges due to resource constraints, which might have created a systematic bias across results. The largest constraint of the study was the simplistic nature of the research design, due in part by the need to keep data collection within the realm of the normal class structure. Within this context, we could neither divide a class between a treatment and a control group nor ad-minister the game twice to the same students within the same course. Future researchers should consider use of a more rigorous research design, such as a pre–posttest structure or utilizing a control cohort as a valid basis for comparative analysis. While there were limitations to the empirical re-search design, its simplicity helped to produce interpretable and actionable results in a timely manner.

From Unassessable to Reportable

Developing business students with the ability to make ethical decisions should be at the forefront of curriculum enhance-ment and demonstrated learning. Making ethical decision making a part of the AoL program should be approached bravely and with assurance. With many faculty members al-ready exploring ways to teach EDM, administrators should embrace ethics as part of their AoL for the future business and community leaders. We hope that this paper contributes to the cause.

REFERENCES

Alexander, A. (2009, July 12). A sponsorship scandal at the post. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/11/AR2009071100290.html

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools in Business. (2007).Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accreditation. St. Louis, MO: Author.

Baird, C. (2005).Everyday ethics: Making hard choices in a complex world. Ann Arbor, MI: Sheridan Books.

Bertland, A. (2009). Virtue ethics in business and the capabilities approach.

Journal of Business Ethics,84, 25–32.

Borkowski, S. C., & Ugras, Y. J. (1998). Business students and ethics: A meta-analysis.Journal of Business Ethics,17, 1117–1128.

Borowski, P. J. (1998). Manager–employee relationships: Guided by Kant’s categorical imperative or by Dilbert’s business principle.Journal of

Busi-ness Ethics,17, 1623–1633.

Bruton, S. V. (2004). Teaching the golden rule.Journal of Business Ethics, 49, 179–189.

Dyck, B., & Kleysen, R. (2001). Aristotle’s virtues and management thought: An empirical exploration of an integrative pedagogy.Business Ethics

Quarterly,11, 561–574.

Gundersen, D. E., Capozzoli, E. A., & Rajamma, R. K. (2008). Learned ethi-cal behavior: An academic perspective.Journal of Education for Business, 83, 315–324.

Gooslby, J. R., & Hunt, S. (1992). Cognitive moral development in

market-ing.Journal of Marketing,56, 55–69.

Herington, C., & Weaven, S. (2007). Does marketing attract less ethi-cal students? An assessment of the moral reasoning ability of under-graduate marketing students.Journal of Marketing Education,29, 154– 164.

Ho, F. N., Vitell, S. J., Barnes, J. H., & Desborde, R. (1997). Ethical cor-relates of role conflict and ambiguity in marketing: The mediating role of cognitive moral development.Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science,25, 117–127.

Kant, I. (2002).Groundwork for the metaphysics of morals. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Klein, H. A., Levenburg, N. M., McKendall, M., & Mothersell, W. (2007). Cheating during the college years: How do business students compare?

Journal of Business Ethics,72, 197–206.

Koehn, D. (2005). Transforming our students: Teachingbusiness ethics post-Enron.Business Ethics Quarterly,15, 137–147.

Krishnan, V. R. (2007). The impact of MBA education on students’ val-ues: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 233– 246.

Ladkin, D. (2006). When deontology and utilitarianism aren’t enough: How Heidegger’s notion of “dwelling” might help organizational leaders resolve ethical issues. Journal of Business Ethics, 65, 87–98.

MacIntyre, A. (1984).After virtue: A study in moral theory(2nd ed.). South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Marens, R. (2007). Returning to justice: Social contracts, social justice, and transcending the limitations of LockeJournal of Business Ethics,75(1), 63–76.

Martell, K. (2007). Assessing student learning: Are business schools making the grade?Journal of Education for Business,82, 187–196.

Mill, J. S. (1776/2003).An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. New York, NY: Bantam.

Prahalad, C. K. (2005).The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: Eradicating poverty through profits. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Phillips, R., & Margolis, J. D. (1999). Towards an ethics of organizations.

Business Ethics Quarterly,9, 619–638.

Ramsay, H. (2007). Insensitivity.The Heythrop Journal,48, 546–560. Rawls, J. (1971).A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press

of Harvard University Press.

Ritter, B. (2006). Can business ethics be trained? A study of ethical decision-making process in business students.Journal of Business Ethics, 68, 153–164.

Solomon, R. C. (1993). Ethics and excellence: Cooperation and integrity in business. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Waples, E. P., Antes, A. L., Murphy, S. T., Connelly, S., & Mumford, M. T. (2009). A meta-analytic investigation of business ethics instruction.

Journal of Business Ethics,87, 153–171.

Wynd, W. R., & Mager, J. (1989). The business and society course: Does it change student attitudes?Journal of Business Ethics,8, 487–491.