Tyler’s

Herbs

of Choice

The Therapeutic Use

of Phytomedicinals

CRC Press is an imprint of the

Boca Raton London New York

Dennis V.C. Awang

Tyler’s

Herbs

of Choice

The Therapeutic Use

of Phytomedicinals

6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742

© 2009 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-7890-2809-9 (Hardcover)

This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher can-not assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint.

Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers.

For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copy-right.com (http://www.copyright.com/) or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that pro-vides licenses and registration for a variety of users. For organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by the CCC, a separate system of payment has been arranged.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Awang, Dennis V. C.

Tyler’s herbs of choice : the therapeutic use of phytomedicinals / Dennis V.C. Awang. -- 3rd ed.

p. cm.

Rev. ed. of: Tyler’s herbs of choice / James E. Robbers, Varro E. Tyler. c1999. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7890-2809-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-7890-2810-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Herbs--Therapeutic use. I. Robbers, James E. Tyler’s herbs of choice. II. Title. RM666.H33R6 2009

615’.321--dc22 2009006363

Dedication

This second revision of Professor Tyler’s original text is

dedicated to his memory. The late Dr. Varro E. “Tip” Tyler

(1926–2001) was a dear friend, a consummate gentleman, and,

undoubtedly, one of the most outstanding botanical medicine

scientists of the twentieth century. His contributions to

aca-demia and to public education, as well as his tireless efforts in

promoting sensible, effective regulation of the herbal industry,

are an everlasting monument to his scientiic preeminence and

Contents

Foreword ...xv

Preface ...xxi

The author ...xxv

1 Chapter Basic principles ... 1

Deinitions ... 1

Differences between herbs and other drugs ... 2

Herbal quality ... 3

Paraherbalism ... 5

Homeopathy ... 7

Rational herbalism ... 9

General guidelines in the use of herbal medicines ... 12

Herbal dosage forms ... 14

Herbal medicine information sources ... 15

References ... 17

2 Chapter Contents and use of subsequent chapters ... 19

References ... 22

3 Chapter Digestive system problems ... 23

Nausea and vomiting (motion sickness) ... 23

Herbal remedy for nausea and vomiting ... 23

Ginger ... 23

Appetite loss ... 27

Signiicant bitter herbs ... 28

Gentian ... 28

Centaury... 29

Minor bitter herbs ... 29

Bitterstick ... 29

Blessed thistle ... 29

Bogbean ... 29

Constipation ... 30

Bulk-producing laxatives ... 30

Psyllium seed ... 31

Stimulant laxatives ... 32

Signiicant stimulant laxatives ... 33

Cascara sagrada ... 33

Buckthorn (frangula) bark ... 34

Senna ... 34

Other stimulant laxatives ... 35

Aloe (aloes) ... 35

Rhubarb ... 35

Diarrhea ... 36

Other antidiarrheal herbs ... 37

Blackberry root ... 37

Blueberries ... 38

Indigestion—dyspepsia ... 38

Carminatives ... 39

Signiicant carminative herbs ... 40

Peppermint ... 40

Chamomile ... 41

Minor carminative herbs ... 43

Anise ... 44

Caraway ... 44

Coriander ... 44

Fennel ... 44

Calamus ... 44

Cholagogues ... 44

Turmeric ... 45

Boldo ... 46

Dandelion... 47

Hepatotoxicity (liver damage) ... 47

Herbal liver protectants ... 48

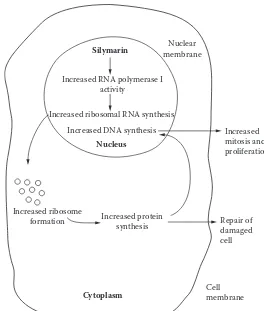

Milk thistle ... 48

Schizandra ... 50

Peptic ulcers ... 51

Plant remedies for peptic ulcers ... 51

Licorice ... 51

Ginger ... 54

References ... 55

4 Chapter Kidney, urinary tract, and prostate problems ... 59

Infections and kidney stones... 59

Goldenrod ... 60

Parsley ... 61

Juniper ... 62

Minor aquaretic herbs ... 63

Birch leaves ... 63

Lovage root ... 63

Antiseptic herbs ... 64

Bearberry ... 64

Anti-infective herbs ... 65

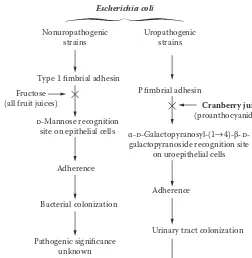

Cranberry ... 65

Cranberry–warfarin interaction?... 68

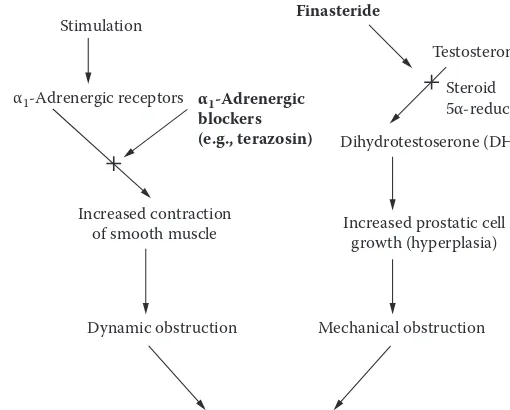

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (prostate enlargement) ... 68

Herbal remedies for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BHP) ... 70

Saw palmetto (sabal) ... 70

Nettle root ... 72

Pygeum ... 73

References ... 73

5 Chapter Respiratory tract problems... 77

Bronchial asthma ... 77

Herbal remedies for bronchial asthma ... 78

Ephedra ... 78

Bitter or sour orange ... 80

Colds and lu ... 81

Demulcent antitussives ... 82

Iceland moss ... 83

Marshmallow root ... 83

Mullein lowers ... 83

Plantain leaf ... 84

Slippery elm ... 84

Expectorants ... 84

Nauseant–expectorants ... 85

Ipecac ... 85

Lobelia ... 85

Local irritants ... 86

Horehound... 86

Thyme ... 86

Eucalyptus leaf ... 87

Surface-tension modiiers ... 87

Licorice ... 87

Senega snakeroot ... 88

Sore throat ... 88

6

Chapter Cardiovascular system problems ... 91

Congestive heart failure ... 91

Herbs containing potent cardioactive glycosides ... 92

Other herbs for treating CHF ... 93

Hawthorn ... 93

Arteriosclerosis ... 94

Herbal remedies for arteriosclerosis ... 95

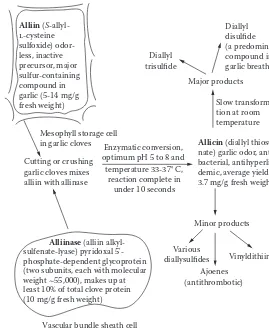

Garlic ... 95

Green tea extract ... 99

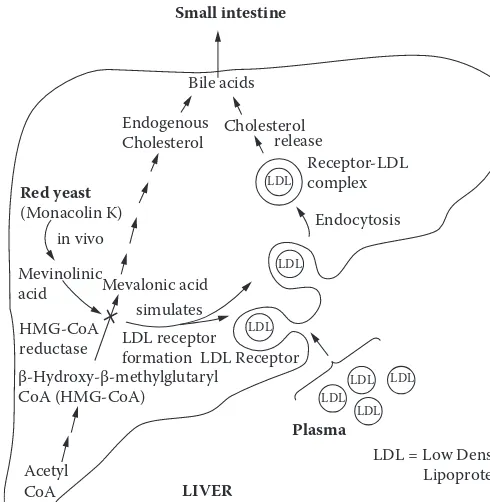

Red yeast ... 100

Policosanol ... 102

Peripheral vascular disease ... 103

Cerebrovascular disease ... 103

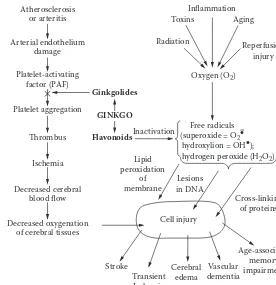

Ginkgo ... 104

Other peripheral arterial circulatory disorders ... 108

Venous disorders ... 108

Varicose vein syndrome (chronic venous insuficiency) ... 108

Horse chestnut seed ... 109

Butcher’s broom ...111

References ...111

7 Chapter Nervous system disorders ... 115

Anxiety and sleep disorders ...115

Herbal remedies for anxiety and sleep disorders ...117

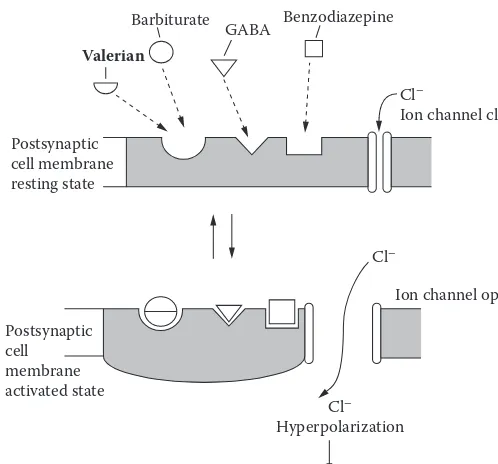

Valerian ...117

Kava ...119

Passion lower ... 120

Hops ... 121

Bacopa ... 122

Gotu kola ... 123

l-Tryptophan ... 124

Melatonin ... 125

Depression ... 128

Herbal remedy for depression ... 129

St. John’s wort ... 129

Pain (general) ... 134

Herbal remedies for general pain ... 135

Willow bark ... 135

Capsicum ... 135

Headache ... 136

Antimigraine herbs ... 137

Feverfew ... 137

Ginger ... 140

Cannabis ... 140

Caffeine-containing beverages ... 140

Toothache ...141

Herbal remedies for toothache ... 142

Clove oil ... 142

Prickly ash bark ... 143

Sexual impotence ... 143

Herbal remedies for sexual impotence ... 144

Yohimbe ... 144

Ginkgo ... 145

References ... 145

8 Chapter Endocrine and metabolic problems ... 151

Hormones in endocrine and metabolic disorders ... 151

Gynecological disorders ... 155

Herbal remedies for gynecological disorders ... 156

Black cohosh ... 156

Chasteberry ... 157

Evening primrose oil ... 158

Black currant oil ... 159

Borage seed oil ... 159

Raspberry leaf ... 159

Hyperthyroidism ... 160

Herbal remedy for hyperthyroidism ... 160

Bugle weed... 160

Diabetes mellitus ... 160

Other herbal remedies for diabetes mellitus ...162

Ginsengs ...162

References ... 163

9 Chapter Arthritic and musculoskeletal disorders ... 167

Arthritis ...167

Herbal remedies for arthritis ... 169

Willow bark ... 169

Feverfew ... 171

Muscle pain ... 171

Rubefacients (agents that induce redness and irritation) ... 172

Volatile mustard oil (allyl isothiocyanate) ... 172

Methyl salicylate ... 173

Turpentine oil ... 173

Refrigerants (agents that induce a cooling sensation)... 173

Camphor ...174

Other counterirritants ...174

Gout ...174

Herbal remedy for gout ...174

Colchicum ...174

References ... 175

10 Chapter Problems of the skin, mucous membranes, and gingiva ... 177

Dermatitis ... 177

Tannin-containing herbs ... 178

Witch hazel leaves ... 178

Oak bark ... 178

English walnut leaves ... 179

Other herbal products ... 179

Contact dermatitis ... 179

Herbal remedy for contact dermatitis ... 180

Jewelweed ... 180

Burns, wounds, and infections ... 180

Herbal remedies for burns, wounds, and infections ... 181

Aloe gel ... 181

Arnica ... 183

Calendula ... 184

Comfrey ... 184

Tea tree oil ... 186

Yogurt ... 187

Lesions and infections of the oral cavity and throat ... 188

Canker sores and sore throat ... 188

Goldenseal ... 188

Rhatany ... 189

Myrrh ... 189

Sage ... 190

Cold sores ... 191

Melissa (balm) ... 191

Dental plaque ... 192

Signiicant herbs ... 192

Bloodroot (sanguinaria) ... 192

Minor herbs ... 193

References ... 193

11 Chapter Performance and immune deiciencies ... 197

Performance and endurance enhancers ... 197

Herbal remedies to treat stress ... 198

Eleuthero ... 202

Sarsaparilla ... 203

Sassafras ... 204

Ashwagandha ... 205

Cordyceps ... 205

Cancer ... 205

Signiicant anticancer herbs ... 206

Catharanthus ... 206

Podophyllum ... 206

Paciic yew ... 207

Unproven anticancer herbs ... 207

Apricot pits ... 207

Pau d’Arco ... 208

Mistletoe ... 208

Chemopreventive herbs... 209

Green tea ... 209

Grape seed extract ... 210

Communicable diseases and infections ...211

Herbal remedies for communicable diseases and infections ... 213

Echinacea ... 213

Cat’s claw ...216

Andrographis ... 217

References ... 218

Appendix: The herbal regulatory system ... 223

Foreword

The growth in consumer use of herbal preparations for health-related pur-poses has generated continuing pressure on educational institutions to train conventional health practitioners in this burgeoning area. Now, more than ever before, pharmacists, physicians, nurses, dietitians, and other professionals are being confronted with situations in which their clients are using a wider variety of dietary supplements for an increasing range of health conditions. Unfortunately, these health professionals often lack adequate training and skills required to assess the overall safety and effec-tiveness of dietary supplements properly. Although varied and numer-ous print and electronic resources are available to help guide health care practitioners in understanding the applications of many herbal and other dietary supplements, there is still a need for basic instruction in this area.

In my own experience at the American Botanical Council (ABC, a non-proit herbal education organization), the many pharmacy student interns who come for six-week clinical rotations as part of their fulillment of the requirements to complete training to become a doctor of pharmacy have no formal training in herbs, phytomedicines, or related subjects. This is certainly also true of the dietitian interns who participate in much shorter, two-week rotations.

Would that they had read and studied this book as part of their professional education! Their patients would beneit greatly from their enhanced basic understanding of the role that herbs and phytomedicinal products can play in both self-care and health care. Health professionals, particularly pharmacy and medical students, will ind that this book is one of the most authoritative introductions to herbs and phytomedicines available in the English language. It is particularly useful as an introduc-tory training manual.

Pharmacognosy is the study of drugs of natural origin, whether derived from plants or animals. Until about the 1970s and 1980s, when it was gradually replaced by medicinal chemistry, pharmacognosy was a required course for all pharmacy students. In pharmacognosy, one would study the plant origins of drugs, where the plants were originally har-vested or cultivated, which plant parts contained the primary active con-stituents, how these constituents were extracted from the plant materials, their pharmacology and toxicology, the microscopy required to identify powdered vegetable drugs, and the chemical tests available to determine the identity of various drug plants. This knowledge was a necessary part of a pharmacist’s education from before the turn of the twentieth century until at least the 1960s or 1970s.

During the 1940s through the 1970s, herbal products—many of which were formerly recognized as oficial medicines in the United States Pharmacopeia—were systematically removed from modern medicine and pharmacy. This decline occurred not because plant preparations were found to be unsafe or ineffective but, rather, primarily because they fell into disuse in conventional medicine and pharmacy, which began to rely increasingly on synthetic, single-chemical pharmaceutical medicines. However, as the use of chemically complex botanical medicines declined in conventional medicine, some of these same plant materials and many others began to migrate to health food stores in numerous forms—as herbal teas, tinctures, capsules, tablets, and other forms.

During the past few decades, millions of Americans, as well as people all over the world, have expressed considerable interest in, and even preference for, natural medicinal products, which go by a number of different names (e.g., herbal remedies, herbal medicines, botanical medicines, herbal medicinal products, traditional medicines, folkloric medicines). Today, this preference for herbal remedies has expanded to an economically signiicant sector; in 2005, the sales of botanical rem-edies in the United States alone was more than $4.4 billion.1 In some countries, particularly Germany and other European nations, the term phytomedicine is preferred; the term usually refers to a plant extract— often “standardized” to contain a guaranteed range of active or marker chemical compounds—with at least a modicum of documented safety and eficacy.

1980s (i.e., to the extent that a college of pharmacy still offered pharma-cognosy in the 1980s).

Eschewing the use of e-mail, Tyler provided faxes to his colleagues with his scrupulously considered editorial corrections, suggestions, com-ments, etc. He was meticulous with a manuscript, catching every mis-spelled word, incorrect phrase, comma splice, and other grammatical problems that often go undetected in contemporary publications.

For six years I taught a course called “Herbs and Phytomedicines in Today’s Pharmacy” in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin. I employed the second edition of this book, the one revised by Professor James E. Robbers, a student and colleague of Professor Tyler’s, as the primary textbook for my students. Their readings were supplemented with some of the American Botanical Council’s books, as well as numer-ous other readings available in ABC’s HerbClip™, now comprising more than thirty-three hundred summaries and critical reviews of the clinical and scientiic literature on herbs.

While reviewing various chapters of Herbs of Choice for the forthcom-ing week’s three-hour lecture, I would sometimes come across statements in the book that I considered inadequate or incomplete in light of more recent advances in the scientiic and clinical literature or recent regulatory developments. In some cases, the range of herbs and herbal preparations discussed by Professor Tyler did not include some herbal preparations that had been subsequently introduced into the North American market and for which a growing body of scientiic and clinical data supported safety and probable eficacy.

At any rate, the dietary supplement market, as well as the clinical literature, was growing and changing. To enable pharmacy students to maintain their grasp on the types of products about which retail phar-macy consumers were anticipated to inquire, Tyler’s Herbs of Choice, like any book, needed some revision.

Professor Tyler and I were scheduled to lead a tour for American pharmacists and physicians of herbs and wines of the Rhine in August 2001. Just back home after a visit in Austria with his wife and partner Virginia, he died suddenly on August 22, 2001—a sad day for the worlds of pharmacognosy and herbal medicine.

On several occasions, I contacted Bill Cohen of Haworth Press to sug-gest that Tyler’s book be revised. Although I sometimes fantasized that I might be the person for the task because I was so familiar with its contents as well as its primary author, I was genuinely heartened and gratiied to learn that my good friend and colleague, Dr. Dennis V. C. Awang, had been asked to do so. With respect to the herb and medicinal plant litera-ture, there is no more knowledgeable expert and no more punctilious edi-tor of this subject in all of North America. I have known him for more than twenty-ive years—ever since he was the key medicinal plant expert in the Canadian government’s former Health Protection Branch, equiva-lent to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

I know of only one other expert in the ield of pharmacognosy and natural products who employs the level of scrutiny that Professor Tyler used to bring to his editorial activities: the author and editor of this revised book, Dr. Awang. As a friend and colleague of Tyler’s, Dr. Awang shared his passion for science, natural products chemistry, and phytomedicines. Both would relish the opportunity to get out their red pens and correct errors in a manuscript intended for publication in a botany, pharmacy, medical, or phytomedicine journal. This newly revised book has Dr. Awang’s ingerprints all over it, and he is a rightful successor to Tyler. Both employ the English language in a highly accurate manner. Awang, one of North America’s most respected and knowledgeable natural prod-ucts chemists, is also a scrupulous editor.

About ifteen years ago, when Dr. Awang was peer-reviewing a man-uscript for publication in ABC’s journal HerbalGram, he sent some remarks that were highly critical of the author’s apparent lack of knowledge of proper botanical taxonomy. When I confronted him on whether he, as a chemist, was adequately qualiied to make such a strong taxonomic criticism, he replied with what I have often referred to as a quintessen-tial Awangian truism: “My dear Mark,” he responded in his impeccable Queen’s English, “everyone knows that it’s much easier for a chemist to learn botany, than for a botanist to learn chemistry!”

or perhaps an interested layperson seeking an authoritative introduction to the vast and highly interesting ield of botanical medicine, there is no doubt that you will ind signiicant value in these pages.

Mark Blumenthal Founder and executive director, American Botanical Council, Austin, Texas;

editor, HerbalGram and HerbClip; senior editor, The Complete German Commission E Monographs—Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines and The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs

References

1. Blumenthal, M., G. K. L. Ferrier, and C. Cavaliere. 2006. Total sales of herbal supplements in United States show steady growth. HerbalGram 71:64–66. 2. Tyler, V. E., L. R. Brady, and J. E. Robbers. 1988. Pharmacognosy, 9th ed.

Preface

Since publication in 1999 of the irst revision of Herbs of Choice, a plethora of publications has extended both the range and depth of herbal medici-nal science. Notable has been the introduction to the West of a number of herbs long popular in Eastern traditional medicine systems. Prominent among these have been Andrographis paniculata, Petasites hybridus (butter-bur), Centella asiatica (gotu kola), Bacopa monnieri, and Citrus aurantium (bit-ter orange) as an ephedra substitute.

There has also been an explosion of concern and scientiic investiga-tion into the potential for herb–drug interacinvestiga-tion inluencing clinical out-comes—from grapefruit (Citrus x paradisi) to St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). Examination of bleeding and coagulation associated with herbs has been expanded. Recent research has also clariied certain aspects of the mechanisms of action of a number of popular herbs, such as feverfew, ginkgo, and ginseng. Particularly, a wholesale revision of the feverfew treatment has been effected. Phytochemical treatment of liver disease and the activity of phytoestrogens have been more widely explored.

The expansion of herbal research in the United States, heralded in the second edition of Herbs of Choice, has markedly increased. Since the 1997 publication of a fair and fairly positive assessment of Ginkgo biloba extract for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), a number of articles have appeared in medical journals, some blatantly deicient in apprecia-tion of herbal scientiic parameters. Conspicuous among the latter have been two JAMA reports1,2 regarding the effectiveness of St. John’s wort (SJW) in major depression, without acknowledging that SJW is recognized for its effectiveness in treating mild to moderate depression. The results of a later study were widely publicized as demonstrating the ineffective-ness of SJW, without noting that the widely prescribed pharmaceutical sertraline was also not signiicantly different in effect from placebo. Most herbal scientists attribute the failure of both test treatments to relatively long-term, chronic serious depression.

focused on two studies that generated negative indings but addressed prevention rather than symptomatic treatment of rhinoviral inoculation. A recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) found no evi-dence of any clinically signiicant eficacy of three extracts of Echinacea angustifolia root.4 The results of that study prompted Samson to criticize the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine for funding investigation of “implausible remedies” and charge a prevalent tendency of herbal enthusiasts to “dismissing disproof.”5 Two other recent NEJM publications report ineffectiveness of three popular herbal remedies: saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia,6 glucosamine-chondroitin for painful knee osteroarthritis,7 and black cohosh for hot lashes.8

The herbal scientiic literature is plagued by mixed results from dif-ferent studies with a number of medicinal plants. These mixed results are widely believed to be due to methodological inadequacies or variation in the chemical character of test treatments.

A recent publication lamented the lack of adequate characterization of herbal supplements subjected to randomized controlled trials (a position long embraced by the late Professor Tyler9) and stressed the importance of quality control issues in ensuring “the value of otherwise well-designed clinical trials.”10 Yet another publication assessed ive popular botanical dietary supplements from nine manufacturers; echinacea, ginseng, kava, SJW, and saw palmetto were analyzed for compliance of marker com-pound content with label claims.11 Although little variability was noted between different lots of the same brand, content of marker compound varied widely between brands, as did information regarding serving rec-ommendations and herbal parameters such as species, part of plant, and marker compounds targeted.

All these considerations recommend much closer attention to all phases of the manufacture of botanical test preparations and committed response to the near-mantra call for larger, better-designed clinical trials of longer duration, with properly characterized treatments.

I am considerably indebted to Kenneth Jones, Armana Research, BC, for contributions to my scientiic information base and for thought-ful and critical discussions of a wide range of herbal medicinal issues. The American Botanical Council’s HerbClip™ service has also been a valuable source of current publications.

References

1. Shelton, R. C., M. B. Keller, A. Gelenberg, D. L. Dunner, R. Hirschfeld, M. E. Thase, et al. 2001. Journal of the American Medical Association 285 (15): 1978–1986.

2. Hypericum Depression Trial Study Group. 2002. Journal of the American Medical Association 287:1807–1814.

3. Knight, V. 2005. Clinical Infectious Diseases 40:807–810.

4. Turner, R. B., R. Bauer, K. Woelkart, T. C. Hulsey, and J. D. Gangemi. 2005. New England Journal of Medicine 353:341–348.

5. Sampson, W. 2005. New England Journal of Medicine 353:337–339.

6. Bent, S., C. Kane, K. Shinohara, J. Neuhaus, E. S. Hudes, H. Goldberg, and A. L. Avins. 2006. New England Journal of Medicine 354:557–556.

7. Clegg, D. O., D. J. Reda, C. L. Harris, M. A. Klein, J. R. O’Dell, M. M. Hooper, et al. 2006. New England Journal of Medicine 354:795–808.

8. Newton, K., S. D. Reed, L. Grothaus, K. Ehrlich, J. Guiltinan, E. Ludman, and A. Z. Lacroix. 2005. Maturitas 16:134–146.

9. Tyler, V. E. 2000. Scientiic Review of Alternative Medicine 4 (2): 17–22.

10. Wolsko, P. M., D. K. Solondz, R. S. Phillips, S. C. Schachter, and D. M. Eisenberg. 2005. American Journal of Medicine 118:1087–1093.

The author

Dennis V. C. Awang, FCIC (fellow of the Chemical Institute of Canada, 1988), is a graduate of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario (BSc, 1960; PhD, 1967). He conducted postdoctoral studies in organic chemistry at the Universities of Michigan and Illinois. Prior to establishing his own consulting busi-ness, Dr. Awang was employed as a research scientist at Health and Welfare Canada for 24 years. At the Bureau of Drug Research of the Health Protection Branch, he directed research in support of the regulatory bureaus of the Drugs Directorate in the areas of drug stability and methodology development for antibiotics, hormones, and natural products. He was also the oficial spokesperson in herbal science for the Canadian government for many years.

Basic principles

Deinitions

Herbs are deined in several ways, depending on the context in which the word is used. In botanical nomenclature, the word refers to nonwoody seed-producing plants that die to the ground at the end of the grow-ing season. In the culinary arts, it refers to vegetable products used to add lavor or aroma to food. But in the ield of medicine, the term has a different, yet speciic, meaning. Here it is most accurately deined as crude drugs of vegetable origin utilized for the treatment of disease states, often of a chronic nature, or to attain or to maintain a condition of improved health. Pharmaceutical preparations made by extracting herbs with various sol-vents to yield tinctures, luidextracts, extracts, or the like are known as phytomedicinals (plant medicines).

In the United States, the choice of an herb or phytomedicine for thera-peutic or preventive purposes is usually carried out by the patient. To state it differently, the herb is self-selected because physicians here are not ordinarily educated in the use of such medicinals. However, in many other countries, herbs and phytomedicinals are prescribed by doctors with considerable frequency.

It cannot be emphasized strongly enough that herbs in their medici-nal sense are drugs. For reasons that will become apparent when the legal concerns regarding herbs are discussed in the Appendix, certain special-interest groups continually emphasize their point of view that medicinal herbs are foods or dietary supplements. Scientiically (although not legally under current law), that is not the case. If they are used in the treatment (cure or mitigation) of disease or improvement of health (diagnosis or pre-vention of disease), they conform to the deinition of the word drug.

category. Widely used on a daily basis as an over-the-counter (OTC) bulk laxative that can be purchased without a physician’s prescription, the seed would be classiied by most users as a drug. The same nutritious seed incorporated into a breakfast cereal is certainly nothing more than a healthful food.

The only way to settle this dilemma is to admit that relatively few plant products defy precise deinition as either foods or drugs. Fortunately, in the vast panoply of herbs, relatively few present this clas-siication problem. Those that do are mostly specialized storage organs of the plants, such as fruits, seeds, or leshy underground parts rich in car-bohydrates. The problem is much less frequently encountered with the lowering tops, leaves and stems, barks, rhizomes, or roots that constitute most herbs. The basic deinition still applies. Herbs used for medicinal purposes are drugs.

Differences between herbs and other drugs

Herbs are different in several respects from the types of puriied thera-peutic agents we have become accustomed to call drugs in the last half of the twentieth century. In the irst place, they are more dilute than the con-centrated chemicals that are familiar to us in the form of aspirin tablets or tetracycline capsules. A simple example will illustrate the difference. One can take caffeine for its stimulatory effects on the central nervous system. The usual dose is 200 mg contained in one or two small tablets, depend-ing on their strength. It is also possible to get the same effect by drink-ing a caffeine-containdrink-ing beverage, such as coffee or tea. Because coffee normally contains between 1 and 2 percent of the active constituent, it is necessary to extract up to 20 g (2/3 oz) of the product to yield that same amount. Tea contains more caffeine—up to 4 percent—but the method of preparation extracts less of it. Probably about 10 g (1/3 oz) of tea would be necessary to yield the same amount of caffeine found in one or two tab-lets. This assumes the beverage would be boiled during its preparation, rather than steeped, as is the usual custom.1

has an onset of action ranging from one-half to two hours and reaches a peak activity level in two to six hours.2

Certain digitalis plants contain both of these active principles along with many others. Proponents of its use argue that it is a very effective and useful drug because its multiplicity of constituents provides a uniform activity of short onset and long duration. Although this is true to some degree, it is also true that the activity of the leaf is dificult to standardize. The presently employed standardization procedure that involves cardiac arrest in pigeons is just one of a long series of biological assays utilizing such animals as frogs, cats, goldish, chick hearts, and even daphnia (water leas) in an attempt to obtain an accurate measure of potency. The ability to measure physiological potency in terms of the weight of a pure chemi-cal entity is one of the principal reasons why administration of a puriied constituent was considered advantageous in the irst place. This concept is not new. It dates back to Paracelsus in the early sixteenth century.3

In addition to containing constituents with a desired activity, herbs often contain other principles that detract from their speciic therapeutic utility. For example, cinchona bark contains some twenty-ive related alka-loids, but the only one recognized as useful in the treatment of malaria is quinine. Thus, if powdered cinchona bark is administered as a treat-ment for malaria, the patient will also receive appreciable amounts of the alkaloid quinidine, a cardiac depressant, and cinchotannic acid, which, because of its astringent properties, would induce constipation.4 Such side effects must be taken into account in the use of medicinal herbs.

Herbal quality

The matter of proper identiication and appropriate quality—that is, lack of adulteration, sophistication, or substitution—is an extremely impor-tant one in the ield of herbal medicine. Many of today’s widely used herbs were once the subject of oficial monographs in The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and The National Formulary (NF). These monographs established legal standards of identity and, subject to the limitations of the methods of the period, quality of the vegetable drugs.

the lay person to determine the quality or even the identity of the plant material by visual inspection. Because government standards of quality are nonexistent in the United States, the buyer is totally dependent upon the reputation of the seller. As a general rule, the larger irms have more to lose if they sell herbs of inferior quality, but some smaller organizations have outstanding reputations for marketing quality materials.

Returning to the matter of standardization of herbs or herbal extracts, it must be noted that the concentration of active constituents in differ-ent lots of supposedly iddiffer-entical plant material is highly variable. First of all, genetic variations exist. Just as one variety of apple tree will produce larger or tastier apples than another, so too will one variety of pepper-mint produce a larger quantity of or more lavorful pepperpepper-mint oil than another, even though the conditions of growth remain identical. These genetic variations in medicinal herbs, many of which are obtained from plants growing in the wild, are not well understood.

Also of great importance to the quality of an herb are the environ-mental conditions under which it is grown. Fertility of the soil, length of growing season, temperature, amount of moisture, and time of harvest are some of the signiicant factors. Processing also plays a role. Some con-stituents are heat labile, and the plant material containing them needs to be dried at low temperatures. Other active principles are destroyed by enzymatic processes that continue for long periods of time if the herb is dried too slowly.

Because few of these factors are precisely controlled even for culti-vated plants, let alone those harvested from the wild, the most effective way to ensure herbal quality is to assay—that is, to establish by some means—the amount of active constituents in the plant material. If the chemical identity of the constituent is known, it or a marker compound indicative of the activity of the herb can usually be isolated and quanti-ied by appropriate physical or chemical methods. If it is unknown, if it is a complex mixture of constituents, or if no marker compound is available, biological assays such as that employed for digitalis must be utilized, at least initially. Once the potency of the herb is known, it can be mixed with appropriate quantities of material of greater or lesser potency to produce a product with deined activity. At the present time, standardization of the most widely used medicinal herbs is becoming quite common.

to be required for effectiveness.6 For many years, the root of prairie dock, Parthenium integrifolium L., was wrongly marketed as echinacea (Echinacea spp.)7 and may still be in some isolated instances. Volatile-oil-containing botanicals often have their aromas enhanced by the addition of quantities of essential oils from other sources. This is said to be a common practice in the beverage herbal tea industry.

Although standardized extracts of ginkgo, ginseng, milk thistle, St. John’s wort, and several other plants are available, the quality of unstan-dardized herbs in the American market today is extremely variable. This presents a problem because it makes the establishment of a speciic dose dificult, if not impossible. It would be more of a problem if it were not for the fact that the therapeutic potency and potential toxicity of the active principles in many herbs are very modest; this, coupled with the great dilution in which they occur in the plant material, renders precise dosage often unnecessary.

It is also this lack of high therapeutic potency, accompanied with reduced side effects, that makes herbs more useful for the long-term treat-ment of mild or chronic complaints than for the rapid healing of acute illnesses. This is well illustrated in the current usage of feverfew as a pre-ventive in cases of migraine or vascular headache. Although the herb has no utility in the treatment of acute attacks, accumulated evidence indicates its effectiveness in preventing such attacks if taken on a regular basis.8

Paraherbalism

Paraherbalism is faulty or inferior herbalism based on pseudoscience.9 It is sometimes dificult to differentiate it from true or rational herbal-ism because its advocates use scientiic and medical terminology, making it appear valid. However, on closer examination, one often inds that in paraherbalism medical claims are unsubstantiated by scientiic evidence, the basis for the use of a particular herb may lack scientiic logic, or clini-cal trials supporting use have been lawed (and sometimes combinations of these), thus providing questionable results. The ten tenets or precepts that distinguish paraherbalism from rational herbalism are worth present-ing here in summarized form. Awareness of them will assist interested persons in distinguishing fact from iction in a ield where the former is scarce and the latter is abundant. Proceed with caution any time one of the following italicized statements appears in an herbal reference work or journal article:

1. A conspiracy by the medical establishment discourages the use of herbs. There is no conspiracy. Relatively few health care practitioners have

2. Herbs cannot harm, only cure.

Some of the most toxic substances known—amatoxins, convallatoxin, aconitine, strychnine, abrin, ricin—are derived from plants. 3. Whole herbs are more effective than their isolated active constituents.

For every example cited in support of this thesis, there is at least one example denying it. In addition, many herbs contain toxins in addition to useful principles. Comfrey is an example.

4. “Natural” and “organic” herbs are superior to synthetic drugs.

Friedrich Wöhler, a German chemist, disproved the “natural” part of this in 1828 when he synthesized urea from inorganic start-ing materials. Yet we still ind persons in this last decade of the twentieth century insisting that vitamin C from natural sources is in some way superior to vitamin C prepared synthetically from glucose. Established limits on pesticide residues probably render treated plants no more harmful than “organic” plants.

5. The “doctrine of signatures” is meaningful.

This ancient belief postulates that the form of a plant part deter-mines its therapeutic virtue. If it were true, kidney beans should cure all types of renal disease and walnuts various types of cere-bral malfunction.

6. Reducing the dose of a medicine increases its therapeutic activity.

There is no proof that this is universally true as espoused by practi-tioners of homeopathy. Positive results obtained by homeopathic treatment are either demonstrations of the placebo effect or of observer bias.

7. Astrological inluences are signiicant.

No scientiic evidence supports this assertion.

8. Physiological tests in animals are not applicable to human beings.

Differences do exist, but there is a high probability of signiicance and applicability when diverse animal species, especially those from different orders, show similar effects.

9. Anecdotal evidence is highly signiicant.

It is extremely dificult to assess the reliability of such evidence. Consequently, it must be viewed simply as one of many factors (animal tests, clinical trials, etc.) that may tend to indicate the therapeutic utility of an herb.

10. Herbs were created by God speciically to cure disease.

This thesis is not testable and should not be used as a substitute for scientiic evidence.

literature containing so much outdated and downright inaccurate infor-mation about the use of herbs that interested individuals, lay or profes-sional, who approach the ield for the irst time become totally confused. Because it serves their purposes, paraherbalists often accept at face value the disproved positive statements of a Renaissance herbalist such as Nicholas Culpeper10 or a folk writer such as Maria Treben.11 However, they discount the indings of modern science that demonstrate the toxicity of an herbal product.12

Paraherbalism has helped perpetuate the erroneous concept held by many in the medical community that herbal remedies have little or no pharmacological effect and, at best, are mere placebos that might do little good but do not cause any harm. Indeed, many physicians associ-ate herbal medicine with worthless nostrums such as the snake oils and patent medicines promoted by the traveling medicine shows of the nine-teenth century, part of a very colorful chapter in American history. On the other hand, some physicians believe that the use of herbs is actively dan-gerous, that claims made for them are outrageous, that harm is possible from self-medicating with them, and that practitioners of herbal medicine use empirical rather than scientiic methods in evaluating their eficacy and safety.13

Homeopathy

Homeopathy is a particularly pernicious form of paraherbalism. In the late eighteenth century Samuel Hahnemann, a German physician, chem-ist, and pharmacchem-ist, formulated its basic principles.14,15 He believed that symptoms of disease were an outward relection of an imbalance in the body, rather than a direct manifestation of the illness itself. Treatment should therefore reinforce these symptoms, and the medicine used should produce similar symptoms in healthy individuals. This is the “law of simi-lars” and is a fundamental tenet of homeopathy; consequently, the name is derived from the Greek homoios, meaning similar, and pathos, meaning suf-fering. Hahnemann and his followers conducted “provings” in which they administered herbs, minerals, and other medicinal substances to healthy people and assessed the symptoms that were produced. These detailed records were compiled into reference books used to match a patient’s symptoms with a corresponding drug. The second and most controversial basic tenet of homeopathy is the “law of ininitesimals,” which decrees that the potency of a drug is inversely proportional to its concentration.

tinctures and powders are then used to prepare the medicinal agent by serial dilution either 1:10, the decimal system designated 1X, or 1:100, the centesimal system designated 1C. After each dilution, the liquid prepara-tions are vigorously shaken and tapped on a resilient surface, a process known as “succussion,” and solid preparations are vigorously pulverized in a mortar and pestle. Most remedies range from 6X (one part per mil-lion) to 30X, but products of 30C or more are marketed.

It is interesting to note that a 30X dilution means that the original sub-stance has been diluted 1030 times; however, this dilution would exceed Avogadro’s number (6.02 × 1023 molecules are present in 1 g molecular weight of a substance), and not a single molecule of the drug would be present. Yet cures are claimed for dilutions as high as 2000X. The belief is that the vigorous shaking, tapping, or pulverizing with each step of dilu-tion transfers the inherent essence, or “spirit,” of the drug to the inert mol-ecules of the solvent or lactose. This mystical phenomenon is completely contrary to everything that is known about the scientiic laws that operate in the physical world.

With only about 300 licensed practitioners—half of them physicians and the rest mostly chiropractors, naturopaths, dentists, veterinarians, or nurses—homeopathy is not widely practiced in the United States. Larger numbers of homeopaths practice in Europe and India. In the United States, the greatest problem arising from homeopathy is that homeopathic rem-edies have tainted the medical and scientiic communities’ perception of herbal medicine. Because the Homeopathic Pharmacopeia of the United States was developed in the nineteenth century, the majority of the drug entries are herbal medicines; consequently, a major portion of the homeopathic reme-dies available today from practitioners, pharmacies, and health food stores is based on nineteenth-century materia medica—namely, herbal drugs. Unfortunately, these ineffective homeopathic nostrums have been equated with all herbal medicines in general. This is erroneous, and it is important to remember that herbal medicines other than homeopathic preparations may contain potent bioactive chemicals that could be therapeutically efica-cious or could be hazardous to one’s health if not used properly.

The problem is compounded because homeopathic remedies consti-tute the only category of bogus products legally marketed as drugs in the United States. They have gained this unique status because most of these remedies were on the market before the passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. Due to the efforts of U.S. Senator Royal Copeland, who was also a homeopathic physician, homeopathic remedies were exempted from the law that required drugs to be proven safe.

and consumer advocates was submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) calling for that agency to stop the marketing of OTC homeopathic products until they have been shown to meet the same standards of safety and effectiveness as other OTC drugs. The FDA has not acted on this petition, so in the meantime, it is recommended that phar-macies not stock homeopathic products and that patients be warned that these products are not proven eficacious.16

Rational herbalism

Paraherbalism and homeopathy have done much to discredit herbal medicine, and those seeking to establish its validity start with a severe handicap. Nevertheless, a knowledge of historical drug development will indicate immediately that plants have long served as a useful and rational source of therapeutic agents. Not only do plant drugs such as digitalis, the opium poppy, ergot, cinchona bark, psyllium seed, cascara sagrada, rauwolia, belladonna, and coca leaves continue to serve as useful sources of pharmaceuticals, but their constituents also serve as models for many of the synthetic drugs used in modern medicine.

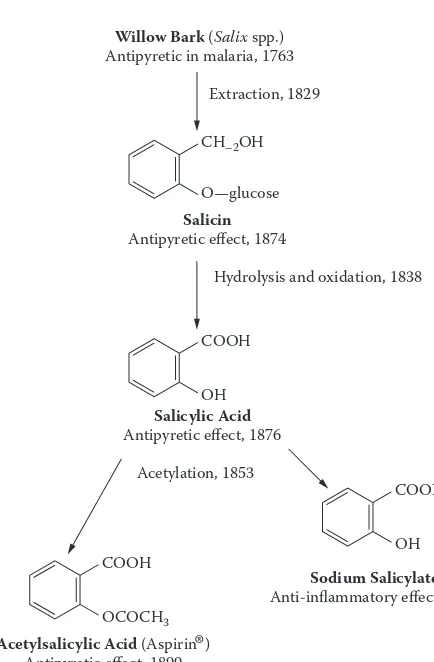

With few exceptions, drug development has followed a logical pro-gression from an unmodiied natural product, usually extracted from an herb, to a synthetic modiication of that natural chemical entity to a purely synthetic compound apparently showing little relationship to its natural forebears. An example of this type of development, illustrated in Figure 1.1, can be seen with the widely used drug ibuprofen. It was intro-duced to the American market in 1974 as one of the irst of a new gen-eration of nonsteroidal anti-inlammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs possess chemical structure features similar to those found in aspirin (ace-tylsalicylic acid) and were developed to reduce undesirable side effects associated with prolonged aspirin usage such as increased bleeding ten-dencies and gastrointestinal irritation.

At the present time the production of NSAIDs for the treatment of pain, fever, and inlammation represents sales worth billions of dollars per year for the drug industry in the United States alone. It is amazing when one considers that this enormous NSAID production all grew from the common willow tree. It is just one of numerous examples that show how much the modern pharmaceutical industry owes to its natural-prod-uct heritage.

It is not unreasonable to expect that, of the thirteen thousand plant species known to have been used as drugs throughout the world (some of them for centuries), there are still many with useful therapeutic properties that have been little studied. Thus, although we may as yet be unable to isolate, purify, and market a botanical’s chemical constituent for use as a drug, the herb that contains it may still be used in its natural or phytome-dicinal form, and desirable therapeutic effects may be achieved.

Willow Bark (Salix spp.)

Antipyretic in malaria, 1763

Salicin Antipyretic effect, 1874

Acetylsalicylic Acid (Aspirin ) Antipyretic effect, 1899

Analgesic effect, 1900

Salicylic Acid Antipyretic effect, 1876

Sodium Salicylate Anti-inflammatory effect, 1877 Extraction, 1829

CH–2OH

O—glucose

Hydrolysis and oxidation, 1838

Acetylation, 1853 COOH

OH

COONa

OH COOH

[image:32.441.90.307.51.382.2]OCOCH3

It is, therefore, important to realize that, although herbs are literally diluted drugs, the nature of the active principles in them is often a matter of empirical observation and tradition rather than the result of extensive clinical testing. The reasons for this lack of clinical testing are basically economic because the cost of such evaluation is extremely high.

However, perhaps even more important than whether an herbal remedy works (i.e., has the desired therapeutic utility) is the matter of whether it is safe. It might be surmised that herbs consumed by humans for generations, centuries, and even millennia must be reasonably safe. This has generally proven true, at least insofar as acute toxicity is con-cerned. But it is not necessarily true for some of the newly introduced, more exotic products that are continually being placed on the market by herbal enthusiasts. Nor is it the case for some of the older herbs that have recently been shown to produce deleterious effects of a chronic, more subtle nature following long usage. Certain comfrey species, with their content of toxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids, are an excellent example of this latter kind of herb.19

Some have questioned the validity of herbal medicine because they doubt the wisdom of self-treatment for diseases of any kind, and, as previ-ously noted, most herbal treatments in the United States are self-selected. That this point of view is largely invalid is obvious to anyone who has followed the recent trend in OTC drugs. A number of signiicant drugs, including hydrocortisone, ibuprofen, clotrimazole, and various antihis-tamines, have been converted from prescription to OTC status, and this trend is continuing.

Many books dealing with “unconventional” or “alternative” med-icine contain, along with discourses on such subjects as acupuncture and homeopathy, a chapter or two on herbal medicine. This shows a complete lack of understanding on the part of the authors of such refer-ence works. Rational herbal medicine is conventional medicine. It is merely the application of diluted drugs to the prevention and cure of disease. The fact that the constituents and, sometimes, even the mode of action of these drugs are often incompletely understood and that instruction in their appropriate application is not a signiicant part of standard medical curricula does not in any way detract from their role in conven-tional medicine. If it did, we would be forced to discontinue the use of a number of popular products such as psyllium seed and senna laxatives, together with about 25 percent of our current materia medica that is derived from such sources.

were considered unconventional, almost the entire population of China would fall into that category. Although herbal therapy may not be main-stream American medicine, it certainly is conventional.

General guidelines in the use of herbal medicines

With respect to self-medication with herbal medicines, it is important to know the conditions for which one can treat oneself and those that deserve professional medical care. The occasional pain of a headache or a strained muscle, a mild digestive upset or simple diarrhea, infrequent insomnia, the common cold—all are conditions that are amenable to and usually receive self-treatment. On the other hand, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiac arrhythmia, or cancer requires professional medical care. Self-treatment in such conditions would be utter folly.

Generally speaking, consumers lack the background to diagnose most clinical conditions accurately. Because one disease can mimic another, potentially serious conditions can be misdiagnosed. Effective self-care requires highly informative and understandable package label-ing and patient education materials that emphasize safe, appropriate, and effective use. Unfortunately, in the United States, the FDA does not regu-late herbal medicines as drugs but rather as dietary supplements; con-sequently, health or therapeutic claims cannot be placed on the package label. However, a vast hyperbolic advocacy literature has built up around them, providing product information designed to promote sales, not nec-essarily to inform. This situation increases the need for health care profes-sionals, especially pharmacists, to judge the quality of available products and to interpret the products’ role in preventing and treating disease for the lay consumer.21,22

manufacturer, a batch or lot number, the date of manufacture, and the expiration date.

Technically, most herbal medicines are unapproved drugs. They may have been used for centuries, but substantial data on the effective-ness and safety of long-term use are often lacking. Safety considerations include warnings and precautions relative to the use of a particular herb, drug–drug interactions between prescription medications and the herbal medication, and the fact that certain groups of individuals often experi-ence a higher incidexperi-ence of adverse drug effects that could have dire con-sequences. In the case of warnings and precautions, patients should cease taking an herb immediately if adverse effects (allergy, stomach upset, skin rash, headache) occur.

Another important safety precaution is that herbal use is not recom-mended for pregnant women, lactating mothers, infants, or children under the age of six. In the pregnant woman, most drugs cross the placental bar-rier to some extent, and these expose the developing fetus to potential teratogenic effects of the drug. The irst trimester, when organogenesis occurs, is the period of greatest teratogenic susceptibility and is the criti-cal period for inducing major anatomicriti-cal malformations. In the lactating mother, the potential exists for the secretion of the drug in the mother’s milk, resulting in adverse effects in the nursing infant. The body and organ functions of infants and young children are in a continuous state of development. Changes in the relative body composition (lipid content, protein binding, and body-water compartments) will produce a different drug distribution in their bodies than in adults. Also, many enzyme sys-tems may not be fully developed in infants, particularly neonates, thus producing a slower drug metabolism.

The elderly patient should be particularly cautious in using herbal medicines. It is well documented that the aging process results in a sig-niicant increase in the proportion of body fat to muscle mass and in decreases in renal function, total body water, lean body mass, organ per-fusion, and hepatic microsomal enzyme activity. Such changes may lead to altered absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of drugs that, in turn, could result in an accumulation of a drug in the body all the way to toxic levels.

Herbal dosage forms

Herbs are consumed in various ways, most commonly in the form of a tea or tisane prepared from the dried plant material. Both of these terms refer to what is technically known as an infusion, prepared by pouring boiling water over the herb and allowing it to steep for a period of time. In such cases, the herb and the water are not boiled together. Time of steeping is important, for many of the desired components are not very water soluble. For example, in the case of chamomile, where much of the desired activ-ity is present in the volatile oil, even a prolonged steeping of ten minutes extracts only about 10–15 percent of the desired components.24

Occasionally, an herbal preparation is made by boiling the plant mate-rial in water for a period of time, then straining and drinking the result-ing extract. Technically, the process is called decoctresult-ing, and the resultresult-ing liquid is known as a decoction. Boiled coffee is prepared in this way as opposed to beverage tea, which is an infusion.

The quantity of herb to be extracted is usually rather imprecise, being stated in terms of level or heaping teaspoonfuls. A standard teaspoon-ful of water weighs about 5 g (approximately 1/6 oz) and a heaping tea-spoonful of most herbal materials approximately half that (2.5 g). Very light herbs such as the lower heads of chamomile may weigh only 1.0 g per heaping teaspoonful. The same quantity of a leaf drug might weigh 1.5 g and of a root or bark about 4.5 g. Even these weights are variable according to the degree of comminution (chopping or grinding) of the plant material. Finely powdered herbs are obviously going to have less space among the particles, and an equal volume will weigh more. A heap-ing teaspoonful of inely powdered gheap-inger weighs about 5 g. Standard instructions for the preparation of a tea call for one heaping teaspoonful per cup of water (240 mL or 8 oz). It must be noted that the stated sizes of teaspoons are those established by long-standing convention. Experience indicates that modern teaspoons have a capacity some 25 percent greater than these standards.25 For most herbal preparations, this difference is probably of minor signiicance.

it may be easily swallowed. The most concentrated form of an herb is a solid extract prepared by evaporating all of the solvent used to remove the active constituents from the herb. Extracts are often available in powdered form; 1 g usually represents 2–8 g of the starting material. They are nor-mally encapsulated for ease in administration.

If consumers decide to purchase the herbs themselves, rather than a processed dosage form, they should remember certain guidelines that will help ensure the acquisition of a quality product. Lacking expert knowledge, however, there is no sure way to avoid all of the pitfalls. Buying clean, dried herbs that are as fresh as possible from a reputable source—preferably in a form allowing positive identiication—and ensur-ing freedom from insect infestation by careful inspection is probably the best general advice. Many herbs are valued for their aromatic principles. These are stable in whole plant parts for a longer period of time than in inely powdered material. Such plant parts can easily be reduced to the desired ineness in a small electric coffee grinder just before making a tea. Maintain all herbs in tightly closed, preferably glass containers, away from sunlight and in a cool, dry place.

Herbal medicine information sources

Essential to any type of effective health care is the availability of objec-tive, unbiased information based on truth and accuracy. Unfortunately, in the case of herbal medicine, many information sources are inaccurate and sensationalize or distort the information they contain. In addition, obtaining reliable information on herbs has become a daunting task because there is an herbal medicine renaissance; information sources abound, including, among many others, news magazines and television, books on paraherbalism and herbalism, scientiic and professional jour-nals, and online databases.26

Information on the results of clinical trials is published in peer-reviewed scientiic and professional journals. The peer-review process means that before an article is accepted for publication, it is scrutinized by scientists and professionals working in the same area in order to ensure that the conclusions derived from the results of the study are valid. In addition, peer-reviewed professional journals publish lengthy, detailed observations made by professionals about patients in their care. These patient case histories, although lacking the control-study aspect, provide valuable suggestions of drug effects and potential safety problems.

Books constitute another important and widely used source of infor-mation on herbal medicine. The most valuable volumes are those that evaluate the current scientiic and professional literature and that sup-ply references to this primary literature. Unfortunately, the majority of the books available fall into the category of paraherbalism. These books run the gamut from glossy, expensive picture books with little accurate therapeutic information to books written by herbal medicine practitio-ners who discuss herbs from the viewpoint of their personal bias rather than on the basis of scientiic fact. In general, an important caveat when using any information source is to be particularly cautious if references to the primary literature are lacking. Without these citations, there is no way to check the accuracy of the facts presented.

Finally, a particularly valuable information source on the safety and eficacy of herbs is the German Commission E monographs. They were used extensively in writing this book and are discussed in Chapter 3. Formerly, the information in the monographs was not readily available to those who did not read German; however, a complete English translation is now available.28

These, then, are the basic principles of herbal medicine as they apply to its current practice in the United States. The ield is a curious mix-ture of ancient tradition applied to modern conditions without, in many cases, the beneit of modern science and technology. To be totally effec-tive, the traditional practices must eventually be coupled with up-to-date scientiic methodology. The reason that has not yet been done, except in certain isolated circumstances, will become clear in the Appendix, which examines the present laws and regulations pertaining to herbs in the United States.

Phytomedicines, exactly like other medicines, must stand up to the challenge of modern scientiic evalu-ation. They need no special consideration when it comes to the planning and conduct of clinical tri-als intended to prove their safety and eficacy. The distinctive feature of phytotherapy is its origin, namely, the many years of empirical use of plant drugs. Experience gained during this period should be taken into account, along with clinical testing, in evaluating the effectiveness of phytomedicines.

In 2005, a Swiss–British study evaluated 110 placebo-controlled home-opathy trials and 110 matched conventional-medicine (allhome-opathy) trials. The authors concluded that the effects seen in placebo-controlled trials of homeopathy are compatible with the placebo hypothesis. In contrast, identical methods demonstrated that the beneits of conventional medi-cine are unlikely to be explained by unspeciic effects.17

References

1. Tyler, V. E. 1987. The new honest herbal, 53–56. Philadelphia, PA: George F. Stickley.

2. Robbers, J. E., M. K. Speedie, and V. E. Tyler. 1996. Pharmacognosy and pharma-cobiotechnology, 117–119. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

3. Sonnedecker, G. 1976. Kremers and Urdang’s history of pharmacy, 4th ed., 40–42. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott Company.

4. Robbers, J. E., M. K. Speedie, and V. E. Tyler. 1996. Pharmacognosy and pharma-cobiotechnology, 155–158. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

5. Ziglar, W. 1979. Whole Foods 2 (4): 48–53.

6. Awang, D. V. C., B. A. Dawson, D. G. Kindack, C. W. Crompton, and S. Heptinstall. 1991. Journal of Natural Products 54:1516–1521.

7. Foster, S. 1991. Echinacea: Nature’s immune enhancer, 84–92. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

8. Hobbs, C. 1989. HerbalGram 20:30–33. 9. Tyler, V. E. 1989. Nutrition Forum 6:41–44.

10. Culpeper, N. 1814. Culpeper’s complete herbal and English physician enlarged. London: Richard Evans, 398 pp.

11. Treben, M. 1980. Health through God’s pharmacy. Steyr, Austria: Wilhelm Ennsthaler, 88 pp.

12. Heinerman, J. 1979. The science of herbal medicine, xvi–xxi. Orem, UT: Bi-World Publishers.

13. Weil, A. 1989. Whole Earth Review 64:54–61.

14. Barrett, S., and V. E. Tyler. 1995. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 52:1004–1006.

15. Der Marderosian, A. H. 1996. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association NS36:317–328.

17. Shang, A., K. Huwiler-Müntener, L. P. Nartey, S. Dörig, J. A. C. Sterne, D. Pewsner, and M. Egger. 2005. Lancet 366:726–732.

18. Robbers, J. E., M. K. Speedie, and V. E. Tyler. 1996. Pharmacognosy and pharma-cobiotechnology, 11–13. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

19. Awang, D. V. C. 1987. Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal 120:100–104. 20. Welt am Sonntag, March 23, 1997, p. 40.

21. Tyler, V. E. 1996. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association NS36:29–37.

22. Tyler, V. E., and S. Foster. 1996. Herbs and phytomedicinal products. In Handbook of nonprescription drugs, 11th ed., ed. T. R. Covington, 695–713. Washington, D.C.: American Pharmaceutical Association.

23. Klein-Schwartz, W., and B. J. Isetts. 1996. Patient assessment and consulta-tion. In Handbook of nonprescription drugs, 11th ed., ed. T. R. Covington, 11–20. Washington, D.C.: American Pharmaceutical Association. .

24. Robbers, J. E., M. K. Speedie, and V. E. Tyler. 1996. Pharmacognosy and pharma-cobiotechnology, 87. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

25. Reich, I., E. T. Sugita, and R. L. Schnaare. 1995. Metrology and calculation. In Remington:The science and practice of pharmacy, 19th ed., ed. A. R. Gennaro, 63–73. Easton, PA: Mack Publishing Company.

26. Hoffman, E. 1994. The information sourcebook of herbal medicine, 1–60. Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press.

27. Flieger, K. 1995. Testing drugs in people. In From test tube to patient: New drug development in the United States, 6–11. FDA Consumer Special Report, DHHS pub. no. FDA 95–3168. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services.

28. Blumenthal, M., W. R. Busse, A. Goldberg, T. Hall, C. W. Riggins, and R. S. Rister, eds. 1998. The complete German Commission E monographs: Therapeutic guide to herbal medicines, trans. S. Klein and R. S. Rister. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council.

Contents and use of

subsequent chapters

The herbal monographs found in subsequent chapters do not con-stitute a comprehensive, encyclopedic listing of all of the more than three hundred herbs currently used in Western medicine. Readers who anticipate that approach will not have their expectations realized. The chapters that follow are instead devoted principally to phytomedici-nals that are now considered to be the most useful for treating particu-lar diseases or syndromes. Following brief general discussions of the pathophysiology of the various conditions, monographs of the useful herbs for treating those disorders are arranged in approximate order of their decreasing therapeutic utility. Occasionally, a particular sec-tion will contain brief discussions of herbs that are not particularly effective but are nevertheless included because of their popularity. Several minor carminatives in Chapter 3 are a case in point. A very few herbs considered totally ineffective or even dangerous to use are included for the same reason. Sarsaparilla and sassafras in Chapter 11 are examples.

Simply because an herb is listed does not mean that it should be used for the particular ailment. For example, phytomedicinals have no place in the self-treatment of self-diagnosed heart disease or cancer. Herbs of potential value in such conditions are discussed to bring them to the atten-tion of professionals who are qualiied to use them properly. Hawthorn and taxol are examples. Each monograph must be read carefully to deter-mine the safety, utility, and proper use of the herb discussed there.

The contents of the major monographs follow the same general pat-tern with minor deviations. Ordinarily, the part of the plant used, the scientiic name (Latin binomial followed by author citation), and the plant family are presented irst, but synonyms, unless they are especially meaningful, are ignored. In a work devoted primarily to the therapeutics of useful herbs, enumeration of the multiplicity of common names was deemed unnecessary, as was much pharmacognostical information, such as habitat, production, preservation, and marketing. All of this is readily available elsewhere.

Chemical identiication of the active principles (when known) i