Yeats, Coleridge and the

Romantic Sage

g

Yeats, Coleridge and the

Romantic Sage

MACMILLAN PRESS LTD

Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0–333–74625–2

First published in the United States of America 2000 by

ST. MARTIN’S PRESS, INC.

,Scholarly and Reference Division, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 ISBN 0–312–23022–2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gibson, Matthew, 1967–

Yeats, Coleridge, and the romantic sage / Matthew Gibson. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–312–23022–2 (cloth)

1. Yeats, W. B. (William Butler), 1865–1939—Knowledge—Literature. 2. Yeats, W. B. (William Butler), 1865–1939—Philosophy. 3. Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, 1772–1834—Philosophy. 4. Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, 1772–1834—Influence. 5. English poetry—19th century—History and criticism. 6. Romanticism—Great Britain. 7. Metaphysics in literature. 8. Philosophy in literature. I. Title. PR5908.L5 G53 2000

821'.8—dc21

99–046990 © Matthew Gibson 2000

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission.

No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP.

Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

v

Contents

Acknowledgements vi

List of Abbreviations viii

A Note on the Text xi

Introduction 1

Part I

Personality

91 Phantasmagoria: the Personality of Coleridge

in the Earlier Prose of Yeats 11

2 ‘Escaped from Isolating Method’: Coleridge as

Sage in Yeats’s 1930 Diary 29

Part II

Transcendence and Immanence

553 Reason and Understanding: Coleridge’s

Philosophical Influence on Yeats 57

4 ‘Wisdom, Magic, Sensation’: Coleridge’s ‘Supernatural’

Poems in the Later Poetry of Yeats 86

Part III

Metaphor

115

5 ‘Natural Declension of the Soul’: Yeats and the Mirror 117 6 Towards ‘Berkeley’s Roasting Spit’: Coleridge and

Metaphors of Unity 149

Conclusion 175

Appendix: Yeats’s Coleridge Collection 177

Notes 184

Bibliography 208

Acknowledgements

I should like to extend thanks to the following for the help they have given me in preparing this book: Michael Baron, Carol Peaker, Svetlana Salowska, Deirdre Toomey and Anne Varty, all of whom, in different ways, have helped with either the collection of material or with the preparation of the manuscript.

Special thanks are due to the library of State University of New York at Stonybrook, and to John Kelly and Roger Nyle Parisious for provid-ing me with copies of unpublished material.

Especial thanks, however, are due to Peter Lewis, for having read over earlier drafts of chapters and suggesting changes when I was first preparing this work as a doctoral dissertation, and, of course, to Warwick Gould for his substantial effort when supervising that initial thesis and for providing subsequent advice.

The author and publishers would like to thank the following for per-mission to reproduce copyright material:

The extracts from W. B. Yeats, Autobiographies (London: Macmillan, 1955), Essays and Introductions (London and New York: Macmillan, 1961), Explorations, selected by Mrs W. B. Yeats (London: Macmillan, 1962; New York, Macmillan, 1963), The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats, ed. Peter Allt and Russell K. Alspach (London and New York: Macmillan, 1966), are reproduced by permission of A. P. Watt Ltd, on behalf of Michael B. Yeats.

The extracts from Yeats’s manuscript ‘Diary, begun at Rapallo’ (1930) are reproduced by permission of A. P. Watt Ltd, on behalf of Michael B. Yeats and Anne Yeats.

The extracts from W. B. Yeats and T. Sturge Moore: Their Correspondence, 1901–37, ed. Ursula Bridge (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; New York: Oxford University Press, 1953), are reproduced by permission of Routledge.

The extracts from The Letters of W. B. Yeats, ed. Allen Wade (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1954; New York: Macmillan, 1955), together with

extracts from unpublished letters, are reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press.

The extracts from A Vision by W. B. Yeats; copyright 1937 by W. B. Yeats; copyright renewed © 1965 by Bertha Georgie Yeats and Anne Butler Yeats, are reproduced by permission of Simon & Schuster.

The extracts from Mythologiesby W. B. Yeats, copyright © 1959 by Mrs W. B. Yeats, are reproduced by permission of Simon & Schuster.

The extracts from Autobiographiesby W. B. Yeats, copyright 1916, 1936 by Macmillan Publishing Company, copyrights renewed © 1944, 1964 by Bertha Georgie Yeats, are reproduced by permission of Simon & Schuster.

The extracts from Explorationsby W. B. Yeats, copyright © 1962 by Mrs W. B. Yeats, are reproduced by permission of Simon & Schuster.

The extracts from Essays and Introductions by W. B. Yeats, copyright © 1961 Mrs W. B. Yeats, are reproduced by permission of Simon & Schuster.

The extracts from the poems ‘His Bargain’, ‘The Tower’, ‘An Acre of Grass’, ‘The Seven Sages’, ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’, ‘Coole Park and Ballylee, 1931’, ‘Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen’, ‘Byzantium’, ‘Vacillation’, ‘To Dorothy Wellesley’, ‘Supernatural Songs’, ‘The Phases of the Moon’ and ‘Long-legged Fly’ are reproduced by per-mission of Simon & Schuster from The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats, ed. Peter Allt and Russell K. Alspach; copyright 1928 by Macmillan Publishing Company; copyrights renewed © 1956 by Georgie Yeats; copyright 1933, 1934 by Macmillan Publishing Company; copyright renewed © 1961, 1962 by Bertha Georgia Yeats; copyright 1940 by Georgie Yeats; copyright renewed © 1968 by Bertha Georgie Yeats, Michael Butler Yeats, and Anne Yeats.

The extracts from The Variorum Edition of the Plays of W. B. Yeats, ed. Russell K. Alspach, copyright © 1966 by Russell K. Alspach, are repro-duced by permission of Simon & Schuster.

List of Abbreviations

The standard works by W. B. Yeats and S. T. Coleridge listed below are cited in the text by standard abbreviations, including volume number where appropriate, and page number. Works listed here are not included in the Bibliography at the end of the book.

Yeats

Au Autobiographies(London: Macmillan, 1955). AV B A Vision(London: Macmillan, 1962).

CM W. B. Yeats: A Census of the Manuscripts, by Conrad A. Balliet with the assistance of Christine Mawhinney (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1990). Col. L1,3 The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats, vol. 1: 1865–1895, ed.

John Kelly and Eric Domville; vol. 3: 1901–4, ed. John Kelly and Ronald Schuchard (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986, 1994).

CV A A Critical Edition of Yeats’s A Vision (1925), ed. George Mills Harper and Walter Kelly Hood (London: Macmillan, 1978).

E&I Essays and Introductions (London and New York: Macmillan, 1961).

Ex Explorations, sel. Mrs W. B. Yeats (London: Macmillan, 1962; New York: Macmillan, 1963).

L The Letters of W. B. Yeats, ed. Allan Wade (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1954; New York: Macmillan, 1955). LTSM W. B. Yeats and T. Sturge Moore: Their Correspondence,

1901–1937, ed. Ursula Bridge (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; New York: Oxford University Press, 1953). Mem Memoirs: Autobiography – First Draft, journal transcribed

and edited by Denis Donoghue (London: Macmillan, 1972; New York: Macmillan, 1973).

Myth Mythologies(London and New York: Macmillan, 1959). MYV1,2 The Making of Yeats’s ‘A Vision’: A Study of the Automatic

Script, by George Mills Harper, 2 vols (London: Macmillan, 1987).

NC A New Commentary on the Poems of W. B. Yeats, by A. Norman Jeffares (London: Macmillan, 1984).

NLI MS Manuscript, National Library of Ireland (to be followed by number).

OBMV The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, 1895–1935, chosen by W. B. Yeats (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1936).

UPAN The Ten Principal Upanishads, trans. Shree Purohit Swa¯mi and W. B. Yeats (London and Boston: Faber & Faber, 1937).

UP1 Uncollected Prose by W. B. Yeats, vol. 1, ed. John P. Frayne (London: Macmillan; New York: Columbia University Press, 1970).

UP2 Uncollected Prose by W. B. Yeats, vol. 2, ed. John P. Frayne and Colton Johnson (London: Macmillan, 1975; New York: Columbia University Press, 1976).

VP The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats, ed. Peter Allt and Russell K. Alspach (New York: Macmillan, 1957). To be cited from the corrected third printing of 1966 or later printings.

VPl The Variorum Edition of the Plays of W. B. Yeats, ed. Russell K. Alspach assisted by Catherine C. Alspach (London and New York: Macmillan, 1966). To be cited from the corrected second printing of 1966 or later printings.

VSR The Secret Rose, Stories by W. B. Yeats: A Variorum Edition, ed. Warwick Gould, Phillip L. Marcus and Michael J. Sidnell (London: Macmillan, 1992). To be cited from this second edition, revised and enlarged from the 1981 Cornell University Press edition.

WWB1,2,3 The Works of William Blake, Poetic, Symbolic, and Critical, ed. with lithographs of the illustrated ‘Prophetic Books’, and a memoir and interpretation by Edwin John Ellis and William Butler Yeats, 3 vols (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1893).

YA Yeats Annual, ed. Warwick Gould (London: Macmillan, 1982– ), to be followed by volume number.

YAACTS Yeats: An Annual of Critical and Textual Studies 4, ed. Richard J. Finneran (Ann Arbor: UMI Press, 1986), to be followed by volume number.

1985). To be followed by item number (or page number preceded by ‘p.’).

YVP1,2,3 Yeats’s VisionPapers(London: Macmillan, 1992), George Mills Harper (General Editor) assisted by Mary Jane Harper, vol. 1: The Automatic Script: 5 November 1917– 18 June 1918, ed. Steve L. Adams, Barbara J. Frieling and Sandra L. Sprayberry; vol. 2: The Automatic Script: 25 June 1918–29 March 1920, ed. Sandra L. Sprayberry; vol. 3: Sleep and Dream Notebooks, Vision Notebooks 1 and 2, Card File, ed. Robert Anthony Martinich and Margaret Mills Harper.

Coleridge

AP Anima Poetae, from the Unpublished Note-books of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. Ernest Hartley Coleridge (London: William Heinemann, 1895).

BL1,2 Biographia Literaria, ed. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate, 2 vols (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983); Collected Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. Kathleen Coburn, vol. 7. CL1,2,etc. The Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. Earl Leslie

Griggs, 6 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956).

CN The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. Kathleen Coburn (and Merton Christensen, vols 3 and 4), 4 vols (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1957–90).

CP The Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. James Dykes Campbell (London: Macmillan, 1925 [YL404]). EOT1,2,3 Essays on His Times, ed. David V. Erdmann, 3 vols

(London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978); Collected Works, vol. 3. LL1,2 Lectures, 1808–1819, ed. R. A. Foakes, 2 vols (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987); Collected Works, vol. 5.

LPR Lectures 1795 on Politics and Religion, ed. Lewis Patton and Peter Mann (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1971); Collected Works, vol. 1.

A Note on the Text

The words ‘Mask’ and ‘Daimon’, terms Yeats redefined over several years, are frequently written in italics. This is so as to place the terms, which Yeats used in a variety of works, in the firm context of A Vision, whose terminology is almost entirely italicised. This does not mean that when written in roman the terms are not frequently compatible with their description in A Vision, but simply that they are being used more in terms of the system as portrayed in other works, such as The Trembling of the Veil(1922), or indeed his poetry.

g

Introduction

1

A work with as bold an object as this one requires some apologia before commencing its journey. Scholars of Yeats and Romanticism – Bloom, Bornstein, Adams and others – have charted the various debts which Yeats bore to Shelley, Blake, Keats and Wordsworth in painstaking detail, to the point where much of Yeats’s work has been explained as an attempt to escape the shadow of these powerful forebears, whose images recrystallise under a new aegis in his poetry. A full-scale analysis of Yeats’s reading of Coleridge, however, has seemed improbable given the lack of available evidence that he delighted in this Romantic so much as in others.

Those who have concentrated on Yeats and Coleridge have been few and far between, and even then tend to have done so along unusual lines. Anca Vlasopolos has argued that the method of symbolisation suggested by Coleridge, in Chapter Fourteen of the Biographia and in various Lay Sermons, was the foundation of the Symbolic method practised by Baudelaire and Yeats.1 Robert Snukal, however, examined Yeats’s use of Coleridge’s metaphors of mind in a chapter from his own book on Yeats’s philosophical poems.2 The first is interesting in itself, and correctly observes Yeats’s belief that Coleridge was a precursor of Symbolism, although I would argue that this has more to do with his reading of ‘Kubla Khan’ than any conscious research into Coleridge’s views on symbol. The other book appears to me flawed in its attribu-tions, although this is largely due to the mainly poor understanding of Yeats’s later esoteric work during the epoch when Snukal was writing. The time is ripe for a reappraisal.

of A Visionand Yeats’s reading of philosophy should make us take his debt to Coleridge more seriously. For while Coleridge’s poetry con-tributed rather less than Shelley’s or Blake’s to Yeats’s own, it is also the case that his prose contributed far more than that of any other Romantic figure – than any other mainly ‘literary’ figure – to Yeats’s reading of philosophy after 1925. This gives Coleridge an almost unique importance to Yeats, since the latter in the last part of his career was continually attempting to reconcile the passion of the artist with the abstraction of the philosopher, and that he managed to do so – albeit rather ambivalently – owes much to his reading of this English literary forebear, whose ideas and personality became a lens for com-prehending Anglo-Irish ancestors, Classical and Modern philosophers, as well as a model for his own identity.

How well Yeats understood Coleridge is another matter. In Chapters Nine and Ten of the Biographia Literaria, Coleridge himself described his intellectual journey from Associationism and Unitarianism to tran-scendental idealism and the Church of England, which was accompa-nied politically by a similar movement from Radicalism to Tory Politics and an avid defence of the rights of the propertied classes. Long before Richard Holmes, Coleridge himself loosely drew the divisions between the young, post-Cambridge radical in College Street, Bristol and the permanent resident at Highgate – not particularly faithfully we might complain, as he tried to pretend that both The Watchmanand his par-liamentary sketches for the Morning Post were less anti-establishment than they in fact were. Nevertheless, Yeats had clearly read from Chapter Ten by 1909,3 and had he read nothing else would have understood the antinomies of Coleridge’s youth and middle age.

Despite this, his portrayal of Coleridge’s views frequently pays scant regard to historical accuracy, and even when it does often confuses eras. Yeats occasionally takes an historicist’s eye for Coleridge’s later beliefs when examining the poems of his earlier career, and is quite capable in any case of disregarding the flawed argument of a secondary source to absorb him as he wished. Paradoxically, the consistency and regularity with which he does this reveals a certain pattern, and a degree of thought that is by no means accidental and anecdotal, but systematic in its attempt to assert its own view over the material.

currently, the accepted group of great prose works incorporated certain texts which are no longer considered part of that greatness, and excluded others which are now very much revered. The Biographia Literaria was slowly coming to the attention of a new generation of readers, but had been largely ignored in the nineteenth century,4and nowhere near approaching the seminal popularity of Aids to Reflection: a work adapting Coleridge’s spiritual and ethical philosophy of Reason, Understanding and Sense to the scriptures, and popular among Anglican priests.5 Again Table Talk, a collection of his conversation, largely from Highgate over eleven years, was an enduring success throughout the Victorian era.6Its popularity led Ernest Hartley Coleridge to publish Anima Poetaein 1895, a selection of notebook entries which followed in the same strain as Table Talk, offering ‘a collection of unpublished aphorisms and sentences’ (APxiii–xiv) from a man whose intellectual genius was not in doubt, but whose ability to sustain it over a lengthy period was.

Yeats does not appear to have read either Aids to Reflectionor Anima Poetae, but like many of his generation had certainly read Table Talk, possibly before reading the Biographia, as well as the major poems. He was also no doubt aware of Pater’s essay on Coleridge, included in Appreciations, in which the Oxford sage described him as the last great failure of fixed principles who attempted to create an absolute system in an era of increasing ‘fine gradations’ and relativism (as he perceived his own age).7Wolfgang Iser argues that Pater’s answer to Coleridge’s prob-lem was a step on the path to his daring conclusion to Renaissance,8in which he urges the reader to abandon knowledge for ‘exquisite passions’,9but Pater otherwise reflects accurately the intellectual attitude to the spiritual philosophy which Coleridge spent most of his life work-ing towards, and which magnum opus was eventually expounded by his disciple J. H. Greene to the yawns of thinkers eager for Hegelianism.10

The younger Yeats, impressed by Coleridge’s interest in Swedenborg and Boehme, although failing to understand the intellectual scrutiny he applied to the causes of mysticism, took to both the possible super-natural and Symbolist elements in his work which his contemporaries were beginning to discern. He largely rejected the view of Coleridge as failure, although did develop an image of him as tragic Aesthete out of key with a wretched time, suffering from a spiritual sense blunted by Christianity, naturally inclined to the marvellous. On the other hand, a Coleridge of the ‘lakes’, and simple expression, who was friends with Wordsworth, sits alongside this other image in Yeats’s prose in a way which appears incongruous. The two were ultimately to be fused together improbably in the 1930s, when Yeats looked at Coleridge the philosopher to define a role for himself when trying to ‘set up as sage’.

By 1929, when Yeats first began a systematic reading of Coleridge’s work, the critical idiom had been greatly modified. The major poems were still adored, but the Table Talkhad dropped from view as a charm-ing Victorian curiosity, while the Biographia had gathered enormous esteem thanks to the new self-consciousness about criticism breaking out in the English-speaking world, and had played an important role in the establishment of practical criticism as a pedagogical tool.15 Revisions of Coleridge’s metaphysical and political writings had also served to raise the status of The Friend and works like On the Constitution of Church and State,16as historians of ideas retrospectively acknowledged Coleridge’s important role both in introducing German ideas to England, and as an original thinker in Conservative thought who blended English and German traditions. The view of Coleridge as only capable of evincing brilliance spasmodically came under attack in the early twentieth century, as his meandering prose style was finally able to reach an appreciative audience, now sufficiently versed in intel-lectual history to isolate the original aspects of Coleridge’s thought from its oftentimes tawdry execution.17

This personality was that of the sage – a figure who had appeared in Yeats’s work before, but who was to occupy a slightly different place from this time on as an accommodation of the passionate to the ratio-nal. The image of philosopher provided by Coleridge acted as a reinter-pretation of both philosophy and Romanticism. The sage as a figure in Romantic writing, ambivalent in both Shelley and Keats, became now the spokesperson of a new and exciting form of mysticism, briefly announced in A Visionas an Ultimate Reality which is ‘concrete, sensu-ous, bodily’ (AV B214), but developed in many of the essays and intro-ductory pieces outside, where Yeats was able to enunciate this faith more freely.

The first part of this book, therefore, centres in particular on Yeats’s depiction of Coleridge’s personality in his prose writings. This is of especial importance when seeking to understand Yeats’s reading, since his entire critical method – itself based upon a belief in phantasmagoria and the predominance of spiritual truth – involves an acceptance that the personality and the work are the same. For him a reading of the man was a reading of the work and while this only became finalised in 1917 as the aesthetic theory of self, anti-self and Mask, it had in fact always been his technique of criticism from his meeting with Wilde onwards.18

Yeats’s later depiction of Coleridge is as philosopher, although as a philosopher who empowers the artist and incorporates his methods and aims into the discussion, making ‘logic serve passion’. The second part deals with the realisation of this Mask as a focus for adopting the philosophy of other thinkers into A Vision and then with the impor-tance of Coleridge’s great ‘supernatural’ poems – ‘Kubla Khan’, ‘The Ancient Mariner’ and ‘Christabel’ – on Yeats’s philosophical poetry.

The last and longest section deals with Yeats’s attempt to take not so much the Mask of sage, but of Romantic prose-writer in his essays writ-ten outside A Vision, through his adaptation of metaphors of mind taken mainly from Coleridge but also from other figures. Again, how-ever, the discussion affords insight into how Yeats uses Coleridge to explain different schools of philosophy in a way which makes them understood in Yeats’s own terms of spiritualism and cyclical fatalism, and also to adapt philosophical ideas to passionate ends.

explains many of the aporias to be found in A Vision. In this respect Coleridge’s influence can be considered as seminal.

Much of my argument and the material to be examined derives from the text known as Pages from a Diary Written in Nineteen Hundred and Thirty, which was published in 1944 and edited by Mrs Yeats. While I draw attention to the significant omissions which Mrs Yeats made in preparing the piece for publication, I have kept to her text rather than reverting to the original owing to the great skill she herself exhibited in editing his work, and the unavailability of the manuscript to the gen-eral reader. Yeats was preparing either the diary or at least significant parts of it for publication: whether in the form of a ‘Discoveries’ (1907) or an Estrangement(1926), or as parts for separate essays is hard to tell, but the fact that he wrote it as numbered passages rather than simply day by day, frequently returning to earlier parts to add emendations in the form of footnotes, and laboured over the construction of the more philosophical sections, shows that its ultimate publication five years after his death was not simply the revelation of a private manuscript, but the execution of an original intention. Nevertheless, he never edited it himself, perhaps because of the late publication of A Visionto which it acts as a natural support text, clarifying many of the ontologi-cal problems therein. Mrs Yeats, however, transcribed the majority of the passages very faithfully, making occasional omissions to better express the sense of her husband’s entries, and left certain passages out either because of their too-personal nature, inappropriateness with the final design of A Vision or because of a danger of repetition in the com-plete text. Where necessary, therefore, I have referred to those omis-sions which are poignant. Generally, however, the entries from June to August which deal with the consideration of Coleridge were published undisturbed.

found in the latter’s prose works, rather than in the inner intentional-ity of his poems, and in the prose Yeats alluded consciously to Coleridge, seeing in him a source for philosophical and mystical ideas. Bloom’s approach is far too solipsistic for a study as objective as this, which in part tries to measure the extent and nature of Yeats’s misread-ing against more researched readmisread-ings of the ideas he mistook.

A few words should also be said about my use of primary texts. I have, where possible, used the original owned by Yeats, except in the case of the Biographia Literaria. The reason for making an exception in this case is the number of times to which it is referred and the relative rarity of Yeats’s own edition. While I do refer to Yeats’s copies in end-notes and Appendix, so that crucial evidence is not kept from the reader, citations in the main text are always to James Engell’s and W. Jackson Bate’s edition of the Biographia Literaria(1983).

g

Part I

g

1

Phantasmagoria

: the Personality

of Coleridge in the Earlier

Prose of Yeats

11

When telling of how Lionel Johnson was capable of recounting apoc-ryphal stories from his own life as though they were true, Yeats admit-ted that ‘these conversations were always admirable in their drama, but never too dramatic or ever too polished to lose their casual accidental character; they were the phantasmagoriathrough which his philosophy of life found its expression’ ([1922] Au 306). This comment could easily be seen as referring to Yeats’s own memoirs, as well as to his method of criticism.

The phantasmagoriawas a favourite figure for representing the imagi-nation in the Victorian era. Present in the work of writers such as Le Fanu, and Henry James1– either as a metaphor of mind or as an organ-isational principle – it was the most sophisticated means of creating sudden scene changes in theatre in the nineteenth century, akin to the modern-day slide projector, and thus a potential symbol for the sudden materialisation and replacement of images in the mind. Whereas in some writers it was a useful metaphor for describing the appearance of ghosts and opium-induced phantasies, Yeats used it – long after its redundancy – to represent the imagination as the embodiment of those spirits, now purified of their memories, residing in the Soul of the World or Anima Mundi. For Yeats the phantasmagoria represented a drama, in which real history and real personalities mattered little com-pared with the ‘dramatis personaeof our dreams’ (Ex 56), and which he, as critic and artist, embodied in both his own memoirs and his essays. Spiritual truth was certainly at a premium over the empirical.

certainly includes the ‘artistic self’ (YVP1 162). Yeats’s own form of crit-icism usually paid scant concern to form and rhetoric, but rather con-sisted of the description of the personality he intuited through the writings. From 1909 onwards, he was developing his theory of ‘Mask’, in which the artist attains an aesthetic ‘personality’ completely secondary to his habitual self (Mem139).2

While Yeats’s criticism depended on his own ability to discern the correctdramatis personaof an author through invocation of spirits in a new phantasmagoria, he also understood the writer as having adopted a personality through struggle with his Daimon (Myth 336–7), which again was part of the Anima Mundi, and summoned the discarnate Daimons to its service. In both cases the situation is a drama, a fiction superior to the real because of its ontological basis.3 And while this view may be the latest articulation of Yeats’s understanding of literary creation, as a description of his critical technique it has validity for most of his writing life – that to which his ideas were always leading, one is tempted to say.

In order to display Yeats’s portrayal of Coleridge we must assess chronologically the disparate and eclectic uses of the earlier poet’s name and personality to determine what, if any, consistent picture of him emerged in Yeats’s mind over the years. While doing so we must remember that at no time does Yeats appear to have made any care-fully researched readings of either Coleridge’s personality or his work; nor does he seem to have had any concern for doing so. Yeats’s own ideas absorbed Coleridge and reappropriated him accordingly. This does not mean, however, that Coleridge was altogether an unimpor-tant figure for him in his earlier career. After all, Yeats himself wrote that a young man does ‘men and women’ honour by ‘conferring their names upon his own thoughts’ (1934 [VP837]).

I

transcendental in tendency, remained ever the same in this era. It was an epoch in which, for Yeats at least, the personality and self-expression of the poet dissolves before the essence or mood, which is both eternal and beyond him. Or at least that is what should happen. For even in the most Symbolist of Yeats’s volumes, ‘The Wind Among the Reeds’ (1899), he could never quite escape his older Romantic inheritance and express his personality in spite of himself.4

Yeats was furthermore always using literary history to serve his pur-pose in finding poets who could act as exemplars for the various binary polarities he would set up in his critical pieces in order to explain the tradition to which he felt he belonged, and to which the poets whom he most admired belonged as well. Often, and certainly in the earlier pieces, this would reflect no studied reading of a poet, but a neces-sary understanding – perhaps uninformed – of where the poet lay in relation to himself.

This is certainly the case with Coleridge, to whom the younger Yeats only referred a few times by name in his writings, and even then largely to illustrate his own ideas rather than concentrate on a literary hero. He first mentioned him in a review, on the poetry of R. D. Joyce, written for the 26 November 1886 edition of Irish Fireside:

Poets may be divided roughly into two classes. First, those who – like Coleridge, Shelley and Wordsworth – investigate what is obscure in emotion, and appeal to what is abnormal in man, or become the healers of some particular disease of the spirit. During their lifetime they write for a clique, and leave after them a school. And second, the bardic class – the Homers and Hugos, the Burnses and Scotts – who sing of the universal emotions, our loves and angers, our delight in things beautiful and gallant. They do not write for a clique, or leave after them a school, for they sing for all men.

rare emotions. While R. D. Joyce belongs to the ‘bardic’, and thus has some excuse for writing badly, Coleridge, together with Wordsworth and Shelley, typifies the other group who attract a small audience and give expression in their verse to rare and unusual emotions; what Yeats would more normally call ‘the aesthetic school’ (UP288).

The recognition of Coleridge as aesthetic poet is more a result of Yeats’s need to illustrate his own binary than a concerted effort to express a considered opinion on his work, although it may testify to Yeats’s consciousness of the sophisticated and reflective nature of con-versation poems written by both Coleridge and Wordsworth, such as ‘Lines Written Above Tintern Abbey’ and ‘Frost at Midnight’, and their connection in literary history with the later – and for him preferable – work of Shelley. As a late Victorian he would have read them as part of his education, whether he liked them or not (see Chapter 6, p. 155). Here in the review Yeats was, in effect, making literary history serve his own ideas, and Coleridge’s literary identity – together with that of Shelley and Wordsworth – was fashioned in accordance with this need. Some years later, in a review of Douglas Hyde’s Beside the Fire, for National Observer (28 February 1891), Yeats praised the stories of peas-ant men and women, asking:

And why should Swedenborg monopolise all the visions? Surely the mantle of Coleridge’s ‘man of ten centuries’ is large enough to cover the witch-doctors also. There is not so much difference between them. Swedenborg’s assertion, in the Spiritual Diary, that ‘the angels do not like butter’, would make admirable folk-lore.5

When Yeats next referred to Coleridge it was as an exemplar, and again in relation to Blake, in the essay ‘William Blake and his Illustra-tions to the Divine Comedy’ (1896), while seeking to explain the defects in Blake’s work and character as being a necessary by-product of major strengths:

The errors in the handiwork of exalted spirits are as the more fantas-tical errors in their lives; as Coleridge’s opium cloud; as Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s candidature for the throne of Greece; as Blake’s anger against causes and purposes he but half understood; as the flickering madness an Eastern scripture would allow in august dreamers; for he who half lives in eternity endures a rending of the structures of the mind, a crucifixion of the intellectual body.7

This passage concludes an essay in which he outlined Blake’s doctrine of symbol and allegory and the different techniques that realise the two. Yeats tried to prove that Blake was a forerunner of the Symbolist movement, and discussed his hatred of all empirical forms of creativity. He preferred ‘symbol’ to ‘allegory’, since the former was ‘vision’ and ‘a representation of what exists really and unchangeably’, the expression of the eternal world, while the latter was purely ‘created by the fantasy’, made from ‘memory and whim’ (Savoy, III, 41). In other words, Blake’s theory of imagination was essentially visionary and transcendental.8

Although he agreed with Blake’s preference for the visionary rather than the associative in art, Yeats saw problems in his work:

The technique of Blake was imperfect, incomplete, as is the tech-nique of wellnigh all artists who have striven to bring fires from remote summits; but where his imagination is perfect and complete, his technique has a like perfection, a like completeness.

(III, 54)

endure, like Blake and de l’Isle Adam, ‘a crucifixion of the intellectual body’ (III, 57) – which induced both poor technique in his work, and an ‘error’ in his life.

The method of exemplification used here is as important as the iden-tity assigned to Coleridge, since it affords us insight into Yeats’s method of criticism. He insisted that the errors of the men’s lives actu-ally reflectedthe errors of their handiwork: in Coleridge’s case, his lau-danum addiction. In other words Yeats was comparing Coleridge to Blake in terms of both his work, and his personality, and thus was using the description of his personality to represent his poetry, rather than merely employing his name to illustrate one pole of a binary.

In relation to Coleridge’s identity in the earlier review of R. D. Joyce, the portrayal of him as a visionary poet, with flawed technique and damaged personality, is certainly compatible with the poet of aesthetic integrity who writes for a clique, but by no means identical. Given Blake’s interest in Swedenborgian mysticism and Yeats’s relation of magic to literature, it is also compatible with his other references to him up until this point. We might well be forgiven for seeing a consis-tent attitude to Coleridge emerging in Yeats’s mind, particularly since the view of Coleridge as forerunner of the Symbolist movement would certainly entail for Yeats an occultist bent.

This illusion of consistency, however, is soon modified. In his article on Lionel Johnson’s Ireland for The Bookman (February 1898), Yeats again employed his favourite critical device of opposing binaries, and used Coleridge once more as an exemplar. This time, however, the antinomies were not strictly his own, but were taken from Arthur Henry Hallam’s ‘On some of the Characteristics of Modern Poetry, and on the Lyrical Poems of Alfred Tennyson’ (1833). Hallam had distin-guished between poets of sensation who ‘have “trembled with emo-tions, at colours and sounds and movements unperceived by duller temperaments”, and those of reflection, who bring ideas into their work’.9Hallam’s essay was a welcome explanation to Yeats’s generation for why so much of the poetry of the Victorian era left them cold. The polarities of sensation and reflection seemed to prefigure the later Victorian division between Pater’s philosophy of ‘exquisite passions’10 and Arnold’s belief that poetry should draw upon current ideas to be a ‘criticism of life’.

Club’ as an Aesthete, but to his regret, ‘Mr. Johnson, like Wordsworth and Coleridge, has sometimes written in the manner of the “popular schools”, and “mixed up” with poetry religious and political opinions’ (1898 [UP288–9]).

If we are to understand that Yeats’s division between the two types of poetry in this 1898 review of Johnson was anticipated by his earlier distinction between the poets of the ‘clique’ and the ‘bardic classes’ in 1886, at least in terms of sophistication and popularity, then it must be understood that both Coleridge and Wordsworth have shifted position slightly since then – not to such an extent that they are purely popular poets, but at least to the point of betraying their vision with imported ideas. Whereas before Yeats had seen them as writing for a small audi-ence and as dealing with ‘obscure’ emotions (UP1 105), he now saw them as filling their work with ideas of reflection ‘in the manner of the popular schools’ (UP1 89). Coleridge has also changed since the 1896 essay on Blake’s illustrations, where Yeats deemed him to be a poet who created through transcendental experience and sacrificed the intellectual for the sake of his art. Here, however, the reverse is true, as he sacrifices the body of vision on the cross of intellect, and falls from the company of Blake and de L’Isle Adam.

The motivation for linking Coleridge to this sort of poetry is not pro-vided in the text, but it appears to have been no more than Hallam’s view that the main body of ‘Reflective’ poets in his own century were ‘the Lakers’ (Hallam, p. 92), Wordsworth being his specific example (he admired Coleridge too much to mention him by name).11 Therefore, Yeats rather lamely delivered Coleridge’s name alongside Wordsworth, just as one might add the words ‘and butter’ to ‘bread’, although is slightly kinder than Hallam in seeing them as essentially poets of sensation who befoul their vision. The fact that Shelley, whose name Yeats had originally linked with both these ‘Lakers’ in the review of R. D. Joyce’s work in 1886, was opposed to Wordsworth’s in Hallam’s essay on Tennyson and is similarly contrasted in Yeats’s review of Johnson, illustrates both the extent to which Yeats was influenced by Hallam’s own exemplars, and how firmly he associated the two poets of the Lyrical Ballads together.

point, but castigated for betraying them at another. Yeats had clearly read the more important poems, as well as some of the prose, but allowed neither to make so important an impact on him as that of other Romantics.

II

After the turn of the century, Yeats’s views on art changed dramatically, as he began to seek an aesthetic which was more grounded in the com-mon experience of the people (he was attempting to create an Irish National Theatre), and became convinced that the Aesthetes were only writing from a part of themselves (E&I 266). Having declared that his highly Symbolist, and even Decadent essays of the nineties, collected in the volume Ideas of Good and Evil, were ‘only one half of the orange’ (14 May 1903; Col. L3369), he concluded that all art should be a devel-opment of ‘the habitual self’ (E&I269).

On closer inspection, however, one can discern that Yeats did not quite reject Symbolism out of hand, but rather modified the Symbolist aesthetic to a new environment. He still believed with (pre-Symbolist) Sainte-Beuve that ‘there is nothing immortal except style’ (Ex94) and asserted faith in a literature where form and content, the sound and emotion of language, would be indistinguishable, thus keeping funda-mentally to a Symbolist and transcendental understanding of the word. Where Yeats now differed from before was in his perception of how this can be achieved, seeing that a playwright ‘can write well in … country idiom without much thought about one’s words; the emotion will bring the right word itself, for there everything is old and every-thing alive and noevery-thing common or threadbare’ (1902 [Ex94 –5]). He was beginning to accept, in other words, that an imaginative literature could be founded upon the language of real people rather than upon the artifice of the cliques.

In his essay ‘Literature and the Living Voice’ (Samhain, 1906), Yeats referred to the two authors of the Lyrical Ballads with regard to their attempts to discover ‘simplicity’ in adopting a poetic model which pre-ceded the development of device:

separate accidental from vital things. William Morris, for instance, studied the earliest printing, the founts of type that were made when men saw their craft with eyes that were still new, and with leisure, and without the restraints of commerce and custom. And then he made a type that was really new, that had the quality of his own mind about it, though it reminds one of its ancestry, of its high breeding as it were. Coleridge and Wordsworth were influenced by the publication of Percy’s Reliquesto the making of a simplicity alto-gether unlike that of old ballad-writers.

(1906 [Ex210 –11]) Here Yeats attributed both Coleridge and Wordsworth with success in finding a form nearer to the fundamental ‘principles of life’ in copying Percy’s collection of ballads. In the context of the rest of the essay this means the discovery of a popular language – a living voice – which appeals to an entire people.

Where there is a ‘living voice’ there need be no division between high and low art and there can emerge what Yeats was to call later ‘Unity of Culture’ (1922 [Au295]), as there had been in the sixteenth century, whose culture Yeats observed in a celebration at Killeenan of the bardic poet Raftery, which is mentioned in the essay. One of the reasons for linking Wordsworth and Coleridge to the effort to find a ‘simplicity’ in keeping with his own attempt to find a living voice may well have been not just their use of Percy, but because Wordsworth himself held to a primitivist doctrine of language in writing the Lyrical Ballads. In the Preface to the second edition of the book, Wordsworth described a language derived from men who ‘hourly communicate with the best objects, from which the best parts of language are derived’ (WP, II, 366),12 and which is ‘plainer and more emphatic’, eschewing ‘traditional associations’, a phrase echoed in Yeats’s praise of the language of the uncorrupted peasantry for having less ‘mechanical specialisations and traditions’ (Ex 211). Both, in Yeats’s view, held to a prelapsarian and spiritual view of the language of the ordinary folk, which in his own case translated to the possibility of Unity of Culture if the high artifice of the Anglo-Irish could use the raw strength of that tradition.13

In 1910 Yeats paid tribute to a recently departed colleague in ‘J. M. Synge and the Ireland of his Time’, once more creating a binary and using Coleridge, amongst others, to typify one of the poles:

There are artists like Byron, like Goethe, like Shelley, who have impressive personalities, active wills and all their faculties at the service of the will; but he [Synge] belonged to those who, like Wordsworth, like Coleridge, like Goldsmith, like Keats, have little personality, so far as the casual eye can see, little personal will, but fiery and brooding imagination. I cannot imagine him anxious to impress or convince in any company, or saying more than was suffi-cient to keep the talk circling. Such men have the advantage that all they write is a part of knowledge, but they are powerless before events and have often but one visible strength, the strength to reject from life and thought all that would mar their work, or deafen them in the doing of it; and only this so long as it is a passive act.

(E&I328–9) The distinction here is between two different sorts of imaginative poet: the active re-creator and the passive man who shapes and selects themes from common experience. That Yeats should have created this particular division at all, and have used Coleridge as an exemplar of this ‘passive’ yet ‘brooding’ type of poet, stems from his wish to grind two axes in defending Synge’s genius.

which, although ‘an elaboration of the dialects of Kerry and Aran’, nevertheless ‘checks the rapidity of dialogue’ and so ‘gives direct expression to reverie’ (E&I333– 4).

Yeats’s reason for linking Wordsworth and Coleridge to Synge proba-bly stems from the similar passivity with which they (more properly, Wordsworth) used in writing the Lyrical Ballads, surrendering them-selves to the imaginations of those noble savages who peopled the Quantocks and Cumberland. However, the appearance of their names here also owes something to the same reason why Yeats had used them in ‘Literature and the Living Voice’, meaning that he saw in their work an attempt to create a greater simplicity of language that reflects a more fundamental culture, which is what Synge himself achieved.

In fact, the two notions are linked. Without his passivity before the Aran Islanders, Synge could never have discovered a language ‘so little abstract … so rammed full with life’, yet based upon experience and observation. Percy’s influence apart, we can see from his echoes of the ‘Preface’ in ‘Literature and the Living Voice’ that Yeats linked the simi-lar passivity of Wordsworth before the language derived from men who ‘hourly communicate with the best objects from which the best parts of language are derived’ (Wordsworth, II, 366), to his success in finding a language rid of ‘mechanical specialisations’, and thus saw a parallel with Synge’s attempt to create a new Irish drama that dissolves the dis-tinction between high art and low, by surrendering himself to experi-ence and adapting the language of the peasantry to artistic ends.

Therefore, in 1906 and in 1910, Yeats once again referred to Coleridge, in a way wholly different from any previous reference, and again made history serve his own purpose, recasting the co-author of the Lyrical Balladsas a poet of experience, passivity and simplicity, and reappropriating him into his newly emerging views. Coleridge’s per-sonality in this era was largely dependent upon the way in which Yeats saw Wordsworth – although not exclusively. Yeats may have seen ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ as possessing a ‘simplicity altogether unlike that of old Ballad-writers’ (Ex 211). If he did so, however, the same poem was to help him see Coleridge in an altogether different light over a decade later.

III

based spiritually on the Cambridge Platonist Henry More’s The Immortality of the Soul (although with some interminglings from Swedenborg and Nietzsche),17 Yeats described art as the struggle for personality: not, as earlier, a development of ‘the habitual self’ ([E&I 269] 1907), but as self seeking the anti-self and finding it through the ‘Mask’: that is, the desired role or image. Ontologically, this realises itself as the Daimon, a disembodied form from the Soul of the World, struggling to impose his will upon the living man, and with the two fighting to emulate each other. When the man, who inhabits More’s Terrestrial region, finally achieves his own will, he incarnates the Daimon in the Aereal, which constitutes the ‘cistern of form’ for the spirits in the Celestial or Aethereal region: in other words, man and Daimon meet half-way between the two ontological realms of body and spirit. This adaptation of More’s neo-Platonic system provided Yeats with a theory of art which he never renounced from that point onwards, and was to elaborate still further in A Vision. It also gave him a philosophical basis for his main method of literary criticism, which was to read the work by describing the personality – the embodied anti-self or ‘Mask’ – as perceived in an artist’s work: from now on the exact opposite of the habitual self.

The system was as yet confused, and Yeats still had difficulty distin-guishing between the permanent Daimon – the man’s anti-self – and the impermanent: those other minds from the soul of the world which the two incarnate, having completed their struggle (Myth 335).18 Another problem was the distinction between those Daimons in the Aerealregion, and those who exist in the Aethereal conditions, having become purified beyond all form: for More, these higher beings were not Daimons at all, but the Gods as Plato understood them in Timaeus, the ‘Inhabitants of the Heavens’, since Daimons exist only in the Aereal region before ascending to the state of the Gods (More, p. 271). Again with More there is no struggle between the Terrestrialand the Celestial conditions, merely an ascent. Yeats, as always, was freely adapting an intellectual source to his own ends.

Seeking to explain the difference between two sorts of disembodied spirit, Yeats referred to a poem by Coleridge:

as it were, in the midst of thought or perhaps at moments of crisis a faint voice. Were our masters right when they declared so solidly that we should be content to know these presences that seemed friendly and near but as ‘the phantom’ in Coleridge’s poem, and to think of them perhaps as having, as Saint Thomas says, entered upon the eternal possession of themselves in one single moment?

All look and likeness caught from earth, All accident of kin and birth,

Had passed away. There was no trace Of aught on that illumined face, Upraised beneath the rifted stone, But of one spirit all her own; She, she herself and only she, Shone through her body visibly.

(Myth347) Yeats was attempting to show how the ‘personifying spirits’ whom he divined in either Daimonic struggle, or in the more passive state of evocation, constituted spirits from the higher, Celestialregion, purified of memory – whose condition was that of light, not air, but who would descend to the Aerealcondition when incarnating in the mind of the man. They are to be distinguished from the grosser spirits, whom we see in ghostly apparitions, and who still keep to the Aereal, living out their past lives. Yeats was trying to merge the three hypostases of Henry More’s The Immortality of the Soulwith Swedenborg’s description of the path of the soul after death, which goes from living through its memories, to a higher state of complete purification. Yeats evidently saw Coleridge’s poem as describing the essential nature of these beings whom he had called elsewhere the ‘dramatis personae of our dreams’ (Ex 56 [1914]).

dream! – yet so as it might be Sara, Derwent, and still it was an individ-ual babe and mine.’ After giving the verse, he wrote of the spirit as ‘this abstract self … in its nature a Universal personified, as Life, Soul, Spirit etc.’ (AP 120 –1 [CN II, 2442]). Judging by the passage, Coleridge appears to have been using the poem to illustrate an understanding of love as an innate idea, able to fasten its affections to the same thing yet in a plurality of particular manifestations.20The poem is, no doubt, about a phantom above a grave, but he also believed in using the super-natural to symbolise states of mind and ideas in a way that the habitual simply does not – that ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ outlined in the Biographia.21

Nevertheless, Yeats was again regarding Coleridge as a source for Swedenborgian mysticism, as in 1891. It was this very ground – the idea that the dead spirits ‘no longer remembering their own names’ become ‘the characters in the drama we ourselves have invented’ (Ex55) – which provided him with his own right, as critic, to re-create the personalities of writers as a reading of their work into a new phan-tasmagoria, and even to rewrite history itself upon the grounds of spiri-tual truth, as he does later, quite self-consciously, with ‘The Tragic Generation’. In other words, it allowed him to discern the ‘Mask’ which they themselves had sought, but from his own evocation. Coleridge’s poem helped him to define those grounds – the very basis upon which Yeats in fact criticised him elsewhere.

In ‘The Tragic Generation’ (1922) Yeats goes on to incorporate Coleridge into his phantasmagoria, providing his readers with the most full and considered definition yet of Coleridge as a ‘type’ of poet, as well as the most detailed description of his personality up until this point, not only comparing him, as in 1898, to Johnson, but to Dowson and Beardsley as well. Having recounted numerous tales of Johnson and Dowson’s commensurate brilliance and degeneracy, Yeats concluded:

as before him Shelley and Wordsworth, moral values that were not aesthetic values? But Coleridge of the Ancient Mariner, and Kubla Khan, and Rossetti in all his writings, made what Arnold has called that ‘morbid effort’, that search for ‘perfection of thought and feel-ing, and to unite this to perfection of form’, sought this new, pure beauty, and suffered in their lives because of it. The typical men of the classical age (I think of Commodus, with his half-animal beauty, his cruelty, and his caprice) lived public lives, pursuing curiosities of appetite, and so found in Christianity, with its Thebaid and Mareotic Sea, the needed curb. But what can the Christian confessor say to those who more and more must make all out of the privacy of their thought, calling up perpetual images of desire, for he cannot say, ‘Cease to be artist, cease to be poet’, where the whole life is art and poetry, nor can he bid men leave the world, who suffer from the terrors that pass before shut eyes. Coleridge, and Rossetti, though his dull brother did once persuade him he was an agnostic, were devout Christians, and Stenbock and Beardsley were so towards their lives’ end, and Dowson and Johnson always, and yet I think it but deepened despair and multiplied temptation.

Dark Angel, with thine aching lust To rid the world of penitence: Malicious angel, who still dost My soul such subtil violence!

When music sounds, then changest thou A silvery to a sultry fire:

Nor will thine envious heart allow Delight untortured by desire.

Through thee the gracious Muses turn To Furies, O mine Enemy!

And all the things of beauty burn With flames of evil ecstasy.

Because of thee, the land of dreams Becomes a gathering-place of fears: Until tormented slumber seems One vehemence of useless tears.

every stroke of the brush exhausts the impulse, Pre-Raphaelitism had some twenty years; Impressionism thirty perhaps. Why should we believe that religion can never bring round its antithesis? Is it true that our air is disturbed, as Mallarmé said, by ‘the trembling of the veil of the Temple’, or that ‘our whole age is seeking to bring forth a sacred book’? Some of us thought that book near towards the end of the last century, but the tide sank again.

(Au313–15) The binary used here is essentially the same as Yeats had employed in reviewing Johnson’s poetry in 1898, Hallam’s distinction between poets of ‘reflection’ and ‘sensation’. He now described Arnold (from whose letter he also quoted22), Browning and Tennyson, the most popular poets of the times, as filling their work with ‘impurities’.23 Coleridge, however, is for once contrasted with Wordsworth in being identified as making ‘that search for “perfection of thought and feeling, and to unite this to perfection of form” ’ (Au313).

This view of Coleridge, supported by renewed interest in his ‘super-natural poetry’, casts him in the role of visionary and Aesthete. It shows that by 1922 he associated Coleridge’s best work with Aes-theticism and Symbolism, a possibility all the more likely given com-ments made by Arthur Symons in his edition of Coleridge’s poems that: ‘ “Kubla Khan”, which was literally composed in sleep, comes nearer than any other existing poem to that ideal of lyric poetry which has only lately been systematized by theorists like Mallarmé.’24 Such a judgement would certainly have given Yeats added encouragement to reconstruct Coleridge’s personality on the lines of Baudelaire, Johnson, and Dowson.

an age when it can no longer be understood and when man’s sensibility is the more dispersed.

One reason for seeing Coleridge as a tragic poet in line with Johnson and Dowson is the complication of his religion. As early as 1909 Yeats had been aware of the divisions which Coleridge’s need for a personal God had created between some of the ontological arguments he had espoused at certain points of his life, and had quoted his statement that: ‘My intellect is with Spinoza, but my heart with Paul and the Apostles’25 in a letter to John Quinn of that year (12 January). Now, however, as he accepted the view of Coleridge as precursor of the Tragic Generation of Aestheticist and Symbolist poets, he translated this intellectual schizophrenia to a division between Christian morality and aesthetic purity. The varied portrayals of guilt in ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ and ‘Christabel’ may also have contributed to this view.

Yeats’s description of Johnson and Dowson earlier on lays blame upon the Christianity which they espoused for the dissipation which led to their deaths, the one fascinated by the Catholic conception of evil which his imagination had grasped and his drinking heightened (Au310), the other desiring a condition of ‘virginal ecstasy’ (Au311) which could not be attained. For the occultist who accepts the neces-sity of antithetical polarities the Vision of Evil is perhaps less a ‘tempta-tion’ and more part of a powerful, transcendental experience. But for the Christian, who has been taught to fear evil and attempt to expurgate it, so strong a Vision can only be mortifying. Due to the var-ied impressions he had gleaned concerning him, from prose, poetry and Symons’s portrayal, Yeats here attributed exactly the same tragic disposition to Coleridge.

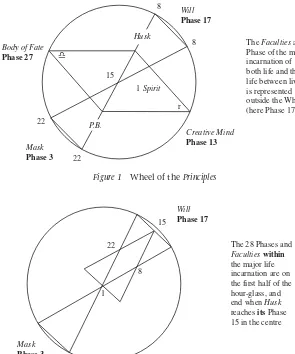

So in the years up until 1922 we see Coleridge variously understood in Yeats’s phantasmagoria as Aesthete and Symbolist poet, as a source for mysticism and as adherent to primitive and popular forms of art. There are some patterns of consistency here, particularly since the tragic Aesthete would have been mystical for Yeats, but no full portrait emerges: rather, two markedly different personalities which would occupy incompatible phases of the moon if placed upon Yeats’s lunar symbolism (13 and 24).

2

‘Escaped from Isolating

Method’: Coleridge as Sage in

Yeats’s 1930 Diary

29

In an unpublished letter of 11 November 1929, Coleridge informed his friend Oliver St John Gogarty that he was ‘just setting out on a study of Coleridge verse and prose’. He was also just off to Rapallo to spend much of the year with Ezra Pound, rewriting A Vision. Yeats’s most intense reading of Coleridge was recorded in a diary begun there in 1930.1Extracts from this were published posthumously fourteen years later as Pages from a Diary Written in Nineteen Hundred and Thirteen, with Giraldus’s portrait by Dulac on the frontispiece to cement its connec-tion with A Vision. It is clear from reading the manuscript diary that while Yeats was planning to publish some parts of it, others, being intensely personal (such as his discussions with his wife’s automatic writing and speech control Dionertes, and comparison of his children’s characters), were left out of the published text by Mrs Yeats as editor. Some entries in the original are barely grammatical memos to himself, while others contain the elaborate sentence structures and rhetorical questions which characterise the best of his late prose, and were being corrected for publication. These latter passages contain extensive refer-ence to Coleridge’s politics and philosophy, and on the whole have been very faithfully transcribed by Mrs Yeats.

perhaps not there. Nevertheless, in the Conservative, anti-democratic impulses which he believed to lie in Burke’s ‘An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs’, and in the anti-realist ontology of Berkeley’s ideal-ism, Yeats discovered a tradition of intellectual thought which was both Anglo-Irish in origin, and anticipatory of Romanticism.

Much has been written about Yeats’s reading of Anglo-Irish Georgians and the role it played in recasting his political identity in the last decade of his life, notably by Donald Torchiana2and Elizabeth

Cullingford.3 Less has been written, however, about the role that

Coleridge played as a lens through which to examine all these strands, and to interpret their work. For a perusal of the diary shows that while Yeats may have been attempting to align himself with earlier Anglo-Irish figures, it was Coleridge who acted as a focus to provide him with a particular concept of philosopher: that of the Romantic Sage.

Yeats’s serious reading of Coleridge in 1930 clearly favoured the ideas of the later Conservative and transcendental idealist over that of the young radical and associationist. So much so, that his consciousness of the older Coleridge led him on occasions to reinterpret the younger. For example, in his first diary entry devoted to the English poet, he wrote:

I find this in Coleridge’s Fears in Solitude: Meanwhile, at home,

All individual dignity and power

Engulfed in Courts, Committees, Institutions, Associations and Societies.

I think of some saying of Mussolini’s that power is the better for hav-ing a Christian name and address. Balzac says that in France before the Revolution a man gathered friends about his table, formed a mimic Court, but since it he satisfies ambition by founding a society and becoming its president or secretary. He seemed to see in such societies and the causes they fostered, personal ambition. Compare the rule of the ‘many’ as described by Swift in his Greek and Roman essay. Balzac and Swift saw predatory instinct where Coleridge saw paralysis.4

(Ex 298)

or the ‘few’. Yeats took what was a reference to the important balances of various strata of government to sanction anti-democracy, and, per-haps impressed with the mature Coleridge’s belief that it was not good practice to extend suffrage to those without landed property (Fr135), read this view into a radical poem by the young Coleridge. The fact that ‘Fears in Solitude’, a conversation poem written about the fear of imminent invasion by France, was castigating the British government for spreading the vices of imperialism, and thus the inability of the conscience to act freely in making moral decisions, was clearly ignored by the eager Yeats.5

He also delighted in another point of parallel he discerned in Coleridge’s ideas, namely the influence of Berkeley:

I find this in Coleridge’s Hexameters written during a temporary Blindness. He is talking of the eye of a blind man:

Even to him it exists, it stirs and moves in its prison;

Lives with a separate life, and ‘Is it the Spirit?’ he murmurs:

Sure it has thoughts of its own and to see is only its language.

These lines written in 1799 ‘during temporary blindness’, must be taken as the sense in which he understood Berkeley, that given by Charpentier: Through the particular we approach the Divine Ideas – not, I think, the Berkeley of the Commonplace Book.6

(Ex298–9)

Berkeley, who argued that esse est percipi, and that things only exist mate-rially in our perceiving them, was already Yeats’s favourite philosopher, being the first he had read after finishing the original edition of A Vision. He was particularly important to Yeats since he allowed him to turn the occultist theory of man and Daimon present in A Visioninto an entire ontological theory (of which more shall be said in the next chapter).

the Necessitarian materialism of Priestley and Hartley,7and by the time

of his retirement to Highgate – the period Yeats most admired – he had already surpassed the more primitive idealism of Berkeley for both Kant and post-Kantian philosophy. Yeats, however, took his cue from John Charpentier’s rather shaky work Coleridge the Sublime Somnambulist, a quasi-biography, translated from the French by M. V. Nugent. Charpentier argued that Coleridge was the originator of poésie pureand the aesthetic of the Symbolist movement, and that he had been heavily influenced by Berkeley (a popular opinion of the time) when writing ‘Christabel’, ‘Kubla Khan’, and ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’,8these last two being works which Yeats had already seen as

in keeping with fin-de-siècletrends. This certainly confirmed the view of Coleridge he had gleaned from reading Symons.

The last three of the five consecutive entries recorded by Yeats in his 1930 diary which deal explicitly with his consideration of Coleridge and the extent to which Coleridge’s ideas coincided with those of Swift, Burke and Berkeley, marks a shift from his work itself and a point of crucial self-examination. In the third entry (dated 6 June) Yeats started to look more directly at the great man’s personality:

Why does Coleridge delight me more as man than poet? Even if I believed, and I do not, the general assumption that he established nothing of value, it would not affect the matter. I think the reason is that from 1807 or so he seems to have some kind of illumination which was, as always, only in part communicable. The end attained in such a life is not a truth or even a symbol of truth, but a oneness with some spiritual being or beings. It is this that fixes our amazed attention on Oedipus when his death approaches, and upon some few historical men. It is because the modern philosopher has not sought this that he remains unknown to those multitudes who thought his predecessors sacred. Perhaps Coleridge needed opium to recover a state which, some centuries earlier, was accessible to the fixed attention of normal man.9

(Ex299)

In the fourth entry on Coleridge (13 June) Yeats went on to equate very introspective questions about his own art with his delight in Coleridge’s personality:

I think the explanation must explain also why, during the most creative years of my artistic life, when Synge was writing plays and Lady Gregory translated early Irish poetry with an impulse that interpreted my own, I disliked the isolation of the work of art. I wished through the drama, through a commingling of verse and dance, through singing that was also speech, through what I called the applied arts of literature, to plunge it back into social life.

The use of dialect for the expression of the most subtle emotion – Synge’s translation of Petrarch – verse where the syntax is that of common life, are but the complement of a philosophy spoken in the common idiom escaped from isolating method, gone back somehow from professor and pupil to Blind Tireisias.10

(Ex299–300)

Finally, after several months in which he had been reading the works of both Coleridge and his four Anglo-Irishmen, and had more recently been comparing and contrasting his own work with Coleridge’s, Yeats synthesised his thought to define both the role which all fulfilled, and the positive aspects in all their writings and personal behaviour which united them and excluded him. The role brought together many ideas (some only partially understood) as he groped for a label that would give unity to his thought on 19 June 1930: