The Likely Economic Impact from the Yogyakarta and Central Java Earthquake

Tulus TambunanKadin Indonesia-Jetro 2006

Just as people living in the provinces of Yogyakarta and Central Java were recovering from the recent

volcanic eruption of Mount Merapi, an earthquake registering 5.9 on the richter scale according to the

Meteorology and Geophysics Agency hit these two regions. People in the nine regencies and city in the

provinces of Yogyakarta and Central Java were affected. The center of the earthquake was estimated at 38

kilometers south in the Indian Ocean and 33 kilometers below the ocean bed. Three regencies - Bantul and

Gunung Kidul in the special region of Yogyakarta and Klaten in Central Java - were hit the hardest in terms of

casualties and material damage. More than 4,500 people dead, many more injured and around 14,000 houses

destroyed. The government’s preliminary estimate of the material loss is Rp2.5 trillion (US$270 million).

Several tourist attractions, such as the Prambanan Hindu temples and the palace of Yogyakarta’s sultan, were

damaged by the earthquake. However, the nearby Borobudur Buddhist temple was not hit (see the map below).

Map of Java Island and the Earthquake Hit Area

This earthquake is part of a series of earthquakes over the last 18 months starting in Aceh and Nias in North

Sumatera that resulted in the tsunami in December 2004, as the moving plates are under the same belt. The

latest earthquake was not linked to the eruption of Mount Merapi. The earthquakes have been moving south

from North Sumatera to West Sumatera with the last one in Lampung province in South Sumatera, the center of

which was in the Sunda Strait (between the islands of Sumatera and Java. When the Lampung earthquake hit

The provincial government of Yogyakarta estimated that the loss of material damage could reach as much as

Rp2.5 trillion, as around 14,000 houses, mostly belonging to medium- to low-income groups, and public

infrastructure such as Yogyakarta’s international airport, railroads and electric plants were either damaged or

destroyed.

Economic impact

1The province of Yogyakarta is historically a distinctive place in Indonesia’s politics and nationhood. It

became the temporary capital city of Indonesia during the war against the Dutch in the late 1940s when the

former Sultan of Yogyakarta, Sri Hamengku Buwono IX, turned over power to former President Soekarno to

defend the unity of the country. Economically, Yogyakarta has a relatively small share in the nation’s GDP,

being only around 1.07% in 2004. The population of Yogyakarta is only around 3.17 million people, or 1.5% of

the total population of Indonesia. The economic profile and distribution of regional output by sector of

Yogyakarta and Central Java are presented, respectively, in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Economic Profile of Yogyakarta and Central Java

Descriptions Yogyakarta Central Java

Area (km2) Population (2005)

Regional GDP (2004; Rp. Million) Regional GDP p.c. (2004; Rp) Inflation (2005; %)

Bank credit (per March 2006; Rp trillion)

3,133.15 3,181,200 21,848,682.1

6,777,908.2 14.98

6.78

32,799.71 33,064,400 175,584,778.8

5,395,505.4 15.97

43 Source: BPS

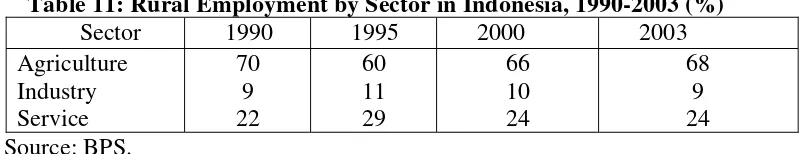

Table 2. Regional GDP Distribution by Sector in Yogyakarta and Central Java, 2004 (%)

Descriptions Yogyakarta Central Java

Agriculture, livestock, forestry & fisheries Mining & quarrying

Manufacturing

Electricity, gas & water supply Construction

Trade, hotel & restaurants Transport & communication

Financial, rental & business services Other services

Total

17 1 15

1 8 19 10 10 19

100

20 1 32

1 6 20

6 4 10

100 Source: BPS

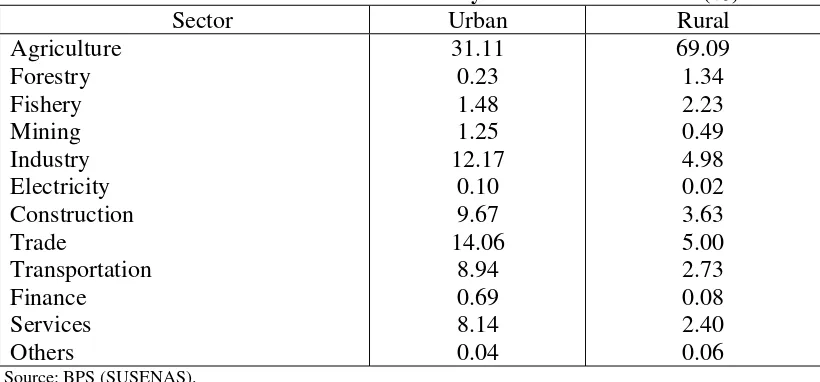

Two areas outside Yogyakarta city (DIY) which are the most destroyed areas are Klaten (in Central Java)

and Bantul (in the Province of Yogyakarta). From a total of more than 6,000 dead, about 3,968 people are in

1

Bantul, compared to 1,680 in Central Java. The most important sector for both Klaten’s and Bantul’s is

agriculture (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Economic Structure of Klaten, 2004 (%)

23%

1%

20%

1% 8%

25% 3%

5%

14%

Agriculture Mining Industry

Electricity, gas and water Construction

Trade, hotel & restaurant Transport & communication Finance, rental & business services Other services

Figure 2: Economic Structure of Bantul, 2004 (%)

23%

1%

20%

1% 8%

18% 7%

7%

15%

Source: BPS

.

The most important sectors for the two provinces’ economy can be elaborated further as the followings:

1) Trade, hotels and restaurants which are very important economic activities in/sources of regional incomes for

Yogyakarta and Central Java (especially Yogyakarta as it together with Bali are still the most important

(Rp38,942,535.04 million) of the regions’ total GDP, respectively; in Yogyarakta, from that 19% share,

restaurants having a 10.3% share;

2) Services make up, respectively, 19% (Rp4,290,460.27 million) and 10% (Rp19,647,530.03 million) of the

regions’ total GDP, dominated by public administration and defense with a 13.0% share in Yogyakarta;

3) Agriculture makes up, respectively 17% (Rp3,636,705.09 million) and 20% (38,492,121.60 million) of the

regions’ total GDP, and in Yogyakarta the sector is dominated by farm food crops with a 12.6% share;

4) Manufacturing industry makes up, respectively, 15% (3,219,137.30 million) and 32% (63,136,563.39

million) of the regions’ total GDP (all non-oil & gas and most of on small-and medium-scale industries

(SMIs) supporting tourism).

Similar to many other smaller regions outside the capital city of Jakarta, Yogyakarta had a surplus of bank

funds of almost Rp6.0 trillion in January 2006. Total third-party funds in the banking sector reached Rp11.52

trillion, while the amount of commercial bank loans in Yogyakarta was only Rp5.69 trillion, or around 0.9% of

total national bank loans. Although having a relatively higher share of loans from rural credit banks at 5.65% of

the total national rural credit bank loans, the nominal amount of rural credit bank loans in Yogyakarta is

considered small at only Rp825 billion. These loans from rural credit banks serve the needs of SMIs, which are

numerous in the area, for working capital and investment credit.

The impact of higher inflation in Yogyakarta due to higher prices for fuel and transportation is unlikely to

push the national inflation rate much higher, as the weight of Yogyakarta in the national consumption price

index (CPI) is a mere 1.22%. However, there is a growing concern about social implications, as GDP per capita

in Yogyakarta is relatively small at only Rp5.9 million (US$690), or only 63.7% of the nation’s GDP per capita.

Provincial minimum wages in Yogyakarta are also low at Rp460,000, which is 56.2% lower than minimum

wages in the capital city of Jakarta.

However, with a cheaper cost of living in Yogyakarta, purchasing power should be relatively unaffected.

The regency of Bantul, the hardest hit area by the earthquake, has a population of almost 800,000 people living

in an area of 506.85 square kilometers. In this regency, the agriculture sector dominates economic activities (at

29.6% of total regional GDP), followed by small scale manufacturing industry (at 18.5% of total regional GDP),

and hotels and restaurants (at 17.07% of total regional GDP).

From the national economy perspective, the total or multiplier impact (i.e. direct or first round and indirect

or second round) of the earthquake in Yogyakarta and Central Java on the Indonesian economy is likely very

small, especially with respect to Yogyakarta. As can be seen in Table 3, the output distribution of Yogyakarta to

GDP is only 1%, compared to that of Central Java at less than 9%.

Table 3: GDP Distribution by Provinces, 2000-2004 (constant prices 2000)

Nangroe Aceh Darussalam

West Kalimantan Central Kalimantan South Sulawesi Southeast Sulawesi

West Nusa Tenggara East Nusa Tenggara Maluku

Impact on the government budget

Vice President Jusuf Kalla announced that the central government will earmark Rp1 trillion of government

spending (around 0.03% of GDP) to help people in the disaster area recover from the emergency situation and

then rebuild the area. On top of that, many countries have offered to give aid (money, medical/health teams and

in kind) to the government to help the earthquake victims. According to a local newspaper, the total amount of

private companies. Additional government spending of Rp1 trillion is not such a big increase for the

government’s budget deficit. Alternatively, with the approval of parliament, the government could also

reallocate some spending to help rebuild the disaster area. Furthermore, the central government budget was still

in surplus of around Rp11 trillion as of 15 May due to slow spending.

Impact on the market

On the first day of trading following the earthquake on 29 May, government bonds were somewhat slightly

better bid, shaking off any negative impact caused by the earthquake over the weekend. Overall, the market was

quiet with some interest in the FR0025, FR0029, and FR0033. The USD/IDR was sold from 9,270 at the

opening to 9,210. There was market talk that bonds will not continue to consolidate until the inflation figure is

released on 1 June. The Jakarta Stock Exchange Composite Index managed to increase 10pts, closing at 1,333

from the close on 25 May. Government bond yields closed at 12.10% -12.20% for mid tenors, with the longer

end staying at an average of 12.20% - 12.30%.

Impact on Small and Medium Enterprises

In Indonesia, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have historically been the main players in domestic

economic activities, especially as a large provider of employment opportunities, and hence a generator of primary

or secondary source of income for many households, especially for the poor. For low income or poor farm

households in rural areas, especially small enterprises (SEs), including micro or household enterprises, in non-farm

activities are especially important. These enterprises have also been playing as an important engine for the

development of local economies and communities (Tambunan, 2006).

The importance of SMEs for the Indonesian economy is observable reflected by their relatively huge

number of units. Indeed, a significant feature of the Indonesian economy is the domination by this category of

enterprises, in particular SEs. Totally, in all sectors of the economy, the number of SEs is huge and it keeps

growing; though there was a decline during the 1997 economic crisis. Their number of units is larger than that of

medium enterprises (MEs) and large enterprises (LEs). Especially SEs can be found in all over the country, in

urban as well as rural areas. Such entities contribute the bulk of units and employment in sectors such as

agriculture, trade, manufacturing industry and transportation (Table 4).

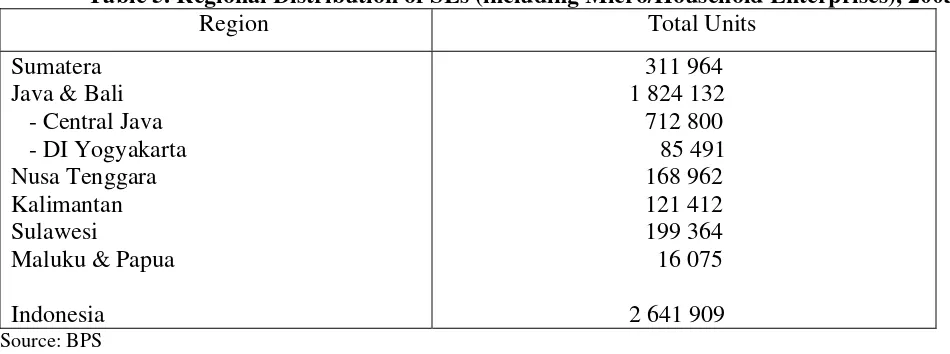

Regionally, the majority of SMEs in all sectors are concentrated in Java, particularly in Central Java,

including the province of Yogyakarta, as the country’s population is also concentrated in this region. As can be

of business with on average 1-4 workers but many of them are self-employment units with family members as

helpers or unpaid workers) are found in Central Java and DI Yogyakarta.

Table 4. Total Enterprises by Size Category

Size Category

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2003 2004

∑ SEs* 39,704,661 36,761,689 37,804,536 38,985,072 40,137,773 42,475,756 43,158,468

∑ MEs 60,449 51,889 51,798 55,061 57,743 59,580 63,361

∑ LEs 2,097 1,831 1,832 1,946 2,095 2,169 2,248

Total 39,767,207 36,815,409 37,858,166 39,042,079 40,197,611 42,537,505 43,224,077 Note: *: including micro enterprises.

Source: Menegkop & UKM

Table 5. Regional Distribution of SEs (including Micro/Household Enterprises), 2003

Region Total Units

Sumatera Java & Bali - Central Java - DI Yogyakarta Nusa Tenggara Kalimantan Sulawesi

Maluku & Papua

Indonesia

311 964 1 824 132 712 800 85 491

168 962 121 412 199 364 16 075

2 641 909 Source: BPS

In manufacturing industry, SMEs are usually clustered together by groups of industry (or subsector of

manufacturing) and regions. The clusters were established naturally as traditional industrial activities of local

communities whose production of specific products have long been proceeding. Based on comparative

advantages of the products they make, at least with respect to the abundance of local raw materials and workers

who have special skills in making such products, many of these clusters have a large potential to grow.

Various studies show the importance of clustering not only for the development of SMEs in the clusters, but

also for the development of villages/towns in Indonesia. Schiller and Martin-Schiller (1997), for instance,

describe how clusters of wood furniture producers in Jepara in Central Java in the 1980s had transformed the

town into a thriving commercial center with a five-mile avenue of furniture showrooms and factories, modern

hotels, new commercial banks, supermarkets, telephone and fax stalls, and European restaurants.

According to their level of development, clusters of SMEs in manufacturing industry in Indonesia can be

1) “Artisinal”: mainly micro or home industries; low productivity and wage; stagnated (no market expansion,

increased investment and production, improved production methods, and management,

organization and production development; local market (low-income consumers) oriented; used

primitive or obsolete tools and equipment; many producers are illiterate and passive in marketing

(producers have no idea about their market); the role of middlemen/traders is dominant

(producers are fully dependent on middlemen or trader for marketing); low degree of interfirm

co-operation and specialization (no vertical cooperation among enterprises); no external

networks with supporting organizations.

2. “Active”: used higher skilled workers and better technology; supplied national and export markets; active in

marketing; the degree of internal as well as external networks is high.

3. “Dynamic”: trade networks overseas are extensive; internal heterogeneity within clusters in terms of size,

technology, and served market is more pronounced; leading/pioneering firms played a decisive

role.

4. “Advanced”: the degree of interfirm specialization and cooperation is high; business networks between

enterprises with suppliers of raw materials, components, equipment and other inputs, providers of

business services, traders, distributors, and banks are well developed; cooperation with local,

regional, or even national government, as well as with specialized training and research institutions

such as universities is good; many firms are export-oriented (mainly through trading houses or

exporting companies).

The first type of cluster dominated clusters in Indonesia, indicating that the process of clustering in the

country is still at an infant stage. Altenburg and Mayer-Stamer (1999) refer to such clusters as “survival”

clusters of home industries. In Yogyakarta, some SMI clusters are predominantly home industries.

The second type developed rapidly in terms of skill improvement, technological upgrading, and successful

penetration of domestic and export markets. Typical examples are such as roof tiles industry clusters, metal

casting industry clusters, shuttle-cock industry clusters, shoe industry clusters, furniture industry clusters, and

brass-handicraft industry clusters that can be found many in Central Java.. In these clusters, some enterprises

start to influence the development trajectory of the clusters, and some enterprises produce for export through

middlemen or traders or trading houses from outside the clusters.

Clusters of the third type often overlap and interlink with other clusters in the same region. Such cluster

agglomerations, or often-called industrial districts (the Italian term), form the most complex form of clustering,

where different sectors or subsectors mutually depend on and benefit from each other. Prominent examples of

machinery industry), southern Germany (vehicle, electronics, machinery, and software industries) and Greater

London (banking, insurance, software, publishing, film and music, tourism, fashion industry, advertising,

business services). In Indonesia, one example of a cluster agglomeration is the Yogyakarta–Solo area (Central

Java) with its tourism, furniture and interior decoration, metal processing, leather goods, and textile/clothing

clusters, which all mutually benefit each other.

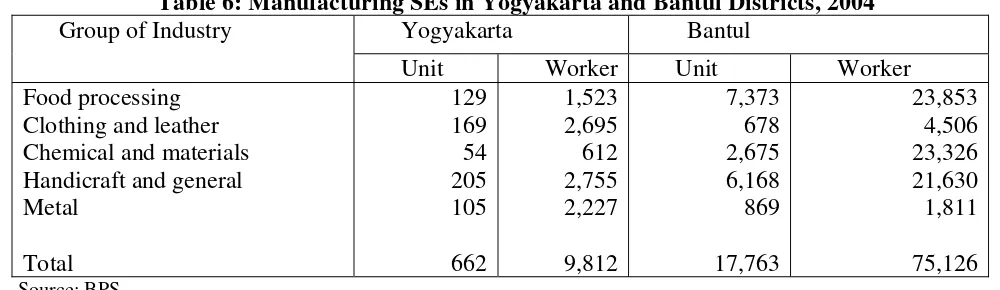

Based on official regional data 2004, in manufacturing industry in Yogyakarta and Bantul districts (within

the Province of Yogyakarta) there were 662 and 17,763 SEs, with total employment of 9,812 and 75.126

people, respectively. The majority of these enterprises were found in handicraft and general industry (Table 6).

In Bantul, there are MEs and LEs, while in Yogyakarta city, in the same period, there were 39 mainly MEs with

a total of 4,076 employees.

Table 6: Manufacturing SEs in Yogyakarta and Bantul Districts, 2004

Yogyakarta Bantul

Group of Industry

Unit Worker Unit Worker

Food processing Clothing and leather Chemical and materials Handicraft and general Metal

Total

129 169 54 205 105

662

1,523 2,695 612 2,755 2,227

9,812

7,373 678 2,675 6,168 869

17,763

23,853 4,506 23,326 21,630 1,811

75,126 Source: BPS

Based on recent official information from the State Ministry of Cooperative and Small and Medium

Enterprises and the Ministry of Industry, a total of 23 SME clusters in Yogyakarta and Central Java are

damaged 25% to 100%. The most damaged clusters (80%) include silver handicraft industry clusters in

Kotagede which consists of 1,500 enterprises. They produce a variety of silver products for export to countries

like Australia, South Africa, and a number of countries in the European Union with minimum 2 to 3 containers

(20 feet) on average per month and for domestic markets in big cities like Bali and Jakarta with minimum 1 to 2

containers on average per month. Others, such as clusters of industries producing gerabah (earthenware vessel)

in Kasongan with 400 units are damaged 90% and industries making kerupuk (chips made of flour slavored) in

Yogyakarta with 138 enterprises are damaged 100%. According to the Office, to put these damaged clusters in

production again about Rp 125 to Rp 150 billions are needed.

The main reasons that they do not produce any more since the earthquake are: (i) factories destroyed; (ii) no

It is generally expected that the stop production of that so many SMEs will hurt the tourism sector not only

in Yogyakarta or Central Java itself but also in Bali. About 60% of handicrafts sold in Bali are originated from

SME clusters in Yogyakarta.

Another most likely effect is that, with the earthquake hitting many SMEs, amount of non-performing loans

(NPL) is expected to increase, despite the possibility of the banking sector extending six months of no default

penalties (similar to what bands did in the tsunami hit area of Aceh). However, with a very small share of credit

extended and a small share of NPL in Yogyakarta (0.33% of total national bank NPL), the impact of increasing

NPL in Yogyakarta on the national NPL is likely to be relatively small.

Impact on Poverty

Historical Trend of Poverty Incidence

By the end of 1960s, the average Indonesian earned only roughly US$50 a year, and over 80% of the

country’s population lived on tiny, fragmented and scattered farms. They had little or no access either to

rudimentary health care or to basic amenities of life such as safe drinking water or adequate shelter. About 60%

of adult Indonesian could not read or write and close to 65% of the country’s population lived in absolute

poverty. However, with a sustained rapid economic growth during the new order (NO) era (i.e. 1966-1998), the

income per capita has increased significantly and the percentage of population deemed as poor has declined

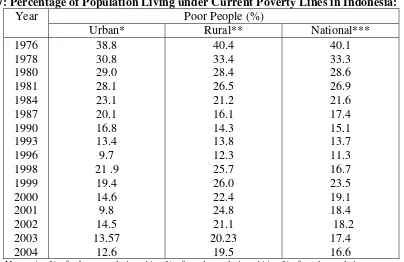

dramatically. The National Socio-Economic Survey (SUSENAS) data from the National Agency of Statistics

(BPS) show that in 1976 the national poverty rate was 40.1% and steadily declined to 11.3% in 1996. When the

crisis occurred in 1997 and reached its climax in 1998, the poverty rate increased to 16.7% and reached its peak

level at 23.5% in 1999. The rebound of the country’s economy in 2000 has led to a drop again in poverty

incidence (Table 7).

As can be seen, in the pre-1997/98 economic crisis period, the poverty rate in rural areas declined faster than

that in urban areas. There were at least three causes: (i) agricultural output growth that led employment in the

sector and farm income to increase; (ii) employment increased in rural non-farm activities like agro-industries,

trade, services and rural transportations as a result of improved rural infrastructure and rural-urban connections;

and (iii) many unskilled labor, unabsorbed by the growth in agriculture and rural non-farm activities, migrated

to urban areas and worked in labor intensive manufacturing industries such as food and beverages, textile and

garments, leather products, electronics and footwear, construction, transportation and services. These were

boomed industries and sectors during the NO era.

The increase of rural poverty during the crisis period was partly a result of returning unemployed people

from urban areas. During the 1997/98 economic crisis, many laid-off workers particularly from manufacturing

to return to their villages where subsistence could at least meet their basic needs. However, in the crisis situation

in which poverty in both urban and rural settings was on the increase, many rural originated people who became

unemployed stayed in cities and considered self-employment or do any kind of low-paid works in urban

informal sector as an option (Amin, 1998; Hugo, 1998). So no doubt that during the crisis agriculture together

with urban informal sector had played an important role as the last resort for the laid off workers from the

formal sector.

Table 7: Percentage of Population Living under Current Poverty Lines in Indonesia: 1976-2004 Poor People (%)

Year

Urban* Rural** National***

1976

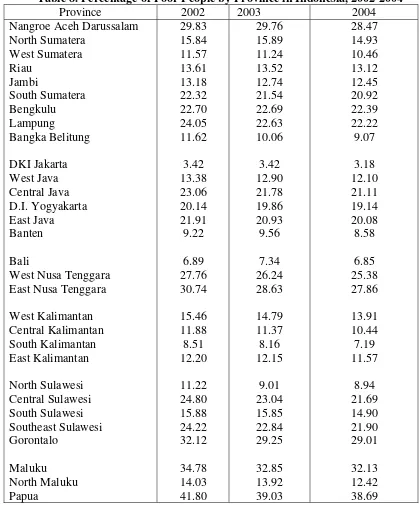

Further, Table 8 shows trends in poverty incidence at the provincial level during 2002-2004. In 2002, Papua,

Maluku, Gorontalo, East Nusa Tenggara, Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam, and West Nusa Tenggara had the highest

proportion of people living below their respectively poverty lines. This condition remained the same until 2004.

However, the trends of poverty incidence during that period indicate that the proportion of people living below

the poverty lines declined in all provinces. In Yogyakarta, the percentage of its total population being poor

Table 8. Percentage of Poor People by Province in Indonesia, 2002-2004

Province 2002 2003 2004

Nangroe Aceh Darussalam North Sumatera

West Nusa Tenggara East Nusa Tenggara

West Kalimantan Central Kalimantan South Kalimantan East Kalimantan

North Sulawesi Central Sulawesi South Sulawesi Southeast Sulawesi

Poverty as An Agricultural Phenomenon

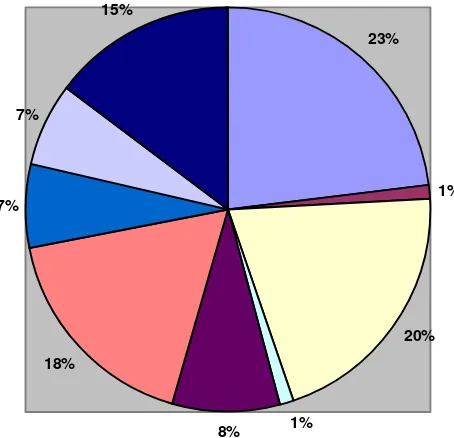

In the Indonesian context poverty is mainly an agricultural phenomenon. That is why agricultural

development has always been the central to poverty reduction in Indonesia for two main reasons. First, although

continuously declining, it remains the largest sector in terms of employment. The National Labour Survey

(SAKERNAS) data from BPS show that in 1971, about 67% of Indonesian total working population worked in

the sector. By 2003, around 46% of the working population still worked in agriculture (Table 9). In fact, during

between 1997 and 1998 the employment share of agriculture in Indonesia increased from 40.8% to 45%

(Feridhanusetyawan, 1999). The pattern of change in employment distribution by sector in Indonesia is also

observable in other important agricultural based economies in Southeast Asia such as China, Vietnam and

Thailand, where other sectors particularly industry manufacturing, construction and services become

increasingly important for employment generation (Figure 3).

Table 9: Employment by Sector in Indonesia, 1990-2003 (%)

Sector 1971 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2003

Agriculture

1985 1990 1995 2000 2003

Indonesia

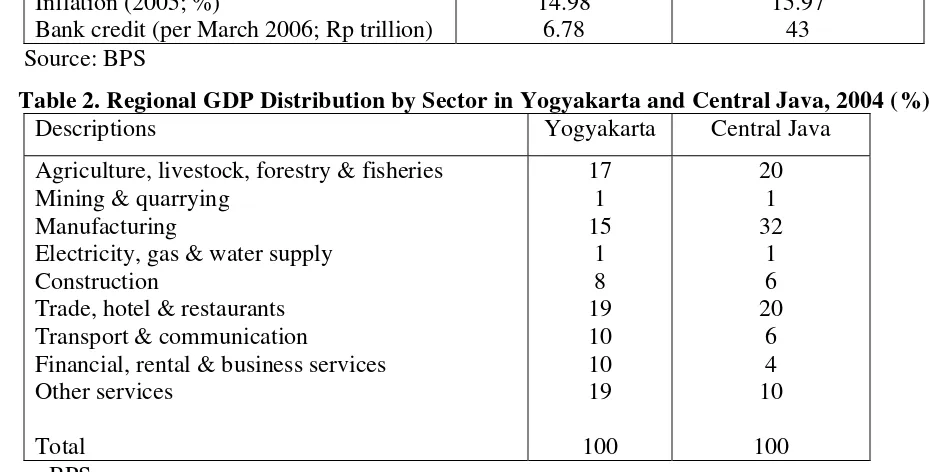

The majority of workforce in Indonesia still finds employment in rural areas. In 1990, about 75% of

Indonesian total workforce worked in rural areas and declined to around 60% in 2003 (Table 10). The largest

part of rural workers was found in the agricultural sector, although the proportion has declined substantially

during the pre-1997-1998 economic crisis period from 75% in 1990 to 60% in 1995. After the onset the crisis,

however, the role of this sector in providing employment opportunities in rural areas regained its importance. In

2003, the proportion of rural workforce absorbed by the agricultural sector has increased again to 68% (Table

Table 11: Rural Employment by Sector in Indonesia, 1990-2003 (%)

Sector 1990 1995 2000 2003

Agriculture Industry Service

70 9 22

60 11 29

66 10 24

68 9 24 Source: BPS.

Consistent with the employment data, a large fraction of Indonesian households particularly in rural areas,

derive their income from agriculture, either as a sole income source or in combination with other sources. Based

on the Intercensal Population Survey (SUPAS) data from BPS in 1995, Table 12 shows that nationally, almost

25% and 23% of all households, respectively, have derived their incomes wholly and partly from the sector. In

rural areas, 72.6% of total households derived at least part of their incomes from the sector.

Table 12: Household Income Sources in Indonesia, 1995 (%)

Income source National Rural Urban

Wholly:

- Agriculture - Non-agriculture Combination

- Mainly agriculture - Mainly non-agriculture

24.9 52.5 22.6 9.9 12.7

46.3 27.4 26.3 13.2 13.1

6.0 84.0 10.0 2.6 7.4 Source: BPS.

Second, the agricultural sector has the highest poverty incidence compared to other sectors and contributes

the largest proportion of the poor in the country. Based on SUSENAS data on distribution of poor families by

main occupations/income source, Table 13 shows the distribution of poor families by sector for the period

1996-2002. Further, Table 14 shows that almost 70% of the poor in rural areas work in agriculture. Even for

urban poor, agriculture is very important as their main source of income. Semi-subsistence urban farming is

widely believed to make an important contribution to the livelihoods of the urban poor in many developing

countries.2Urban agriculture can encompass aquaculture in tanks, ponds, rivers and coastal bays; livestock

(particularly micro-livestock) raised in backyards, along roadsides, in poultry sheds and piggeries; orchards,

street trees, and backyard trees; and vegetable and other crop production on roof tops, in backyards, in vacant

tracts of land on industrial estates, along canals, on the grounds of institutions, on roadsides and in many

peri-urban and peri-urban farms (Gordon, et al., 2000).

2

Table 13: Distribution of Poor Families by Main Occupations/Income Sources, 1996-2002 (%)

Table 14: Distribution of Poor Families by Sector and Area: 2002 (%)

Sector Urban Rural

Agriculture

The meaning of the above shown evidence is that the impact of the earthquake on poverty in Yogyakarta

and Central Java in particular or in Indonesia in general depends much on its effect on production process in

agriculture, and hence on incomes of farm households. There is no information so far indicating that overall

production activity in the agricultural sector in Yogyakarta and Central Java has been hit seriously by the

earthquake; although some local news papers reported about some reductions in production volume experienced

by some individual farmers soon after the tragedy.

References

Altenburg, T., and J. Meyer-Stamer (1999). “How to Promote Clusters: Policy Experiences from Latin America,” World Development, 27(9), 1213–1230.

Amin, A.T.M. Nurul (1998), ‘The Urban Informal Sector in Indonesia: through the economic recession and recovery’, ARTEP Working Papers, No.2, New Delhi: ILO.

Feridhanusetyawan, Tubagus (1999), “The Impact of the Crisis on the Labor Market in Indonesia”, Report for the Asian Development Bank, Jakarta: CSIS.

Gordon, Ann, Junior Davis, Andrew Long and Kate Meadows (2000), ‘The Role of Natural Resources in the Livelihoods of the Urban Poor’, Policy Series 9, Social Sciences Department, Natural Resources Institute University of Greenwich.

Hugo, Graeme (1998), ‘Some comments on the Employment Consequences of the Currency Crisis in Indonesia’, unpublished manuscript, Jakarta: ILO Office.

Sandee, H., and J. ter Wingel (2002), “SME Cluster Development Strategies in Indonesia: What Can We Learn from Successful Clusters?” paper presented for JICA Workshop on Strengthening Capacity of SME Clusters in Indonesia, Jakarta, March 5–6.

Sanyal, B. (1985), ‘Urban agriculture: who cultivates and why? Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 7: 15–24.

Schiller, J., and B. Martin-Schiller (1997), “Market, Culture and State in the Emergence of Indonesian Export Furniture Industry,” Journal of Asian Business, 13(1), 101-16

Tambunan, Tulus T.H. (2006), Development of Small & Medium Enterprises in Indonesia from the Asia-Pacific Perspective, Jakarta” LPFE-Usakti.

![Figure 3: Shares of Total Employed Workers in Agriculture in Selected Southeast Asian Countries [%]: 1985-2003](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/1108407.884196/13.612.76.508.340.466/figure-shares-employed-workers-agriculture-selected-southeast-countries.webp)