Consumer Behaviour at the Generic Level:

Theoretical Perspectives

1Rahmat Hidayat2

Faculty of Psychology Universitas Gadjah Mada

Introduction

1Suppose you had unexpectedly received some money, for instance a gift or a lottery prize. What would you like to do with the money? Why the action you chose to do is of much importance to you? What would you like to achieve by that action? This is a simple illustration of the generic level of consumer decision making, henceforth the generic level. It is important to note that neither money nor unexpec-tedness defines the generic level. Although there are plenty of examples of receiving a windfall, gifts and lottery prizes being two of them, the generic level also concerns situations when expectations rule. For example, people may expect to receive a bumper bonus, an extra profit, a tax return, gain excessive money from a pre-vious budget, or even to inherit some valuable assets from their beloved parents. To a certain degree, people in such situations must ponder of the different ways to utilize the money. The defining features of the generic level concern the mental processes of decision making in which an individual is trying to allocate a consumer resource into different cate-gories of activities (Van Veldhoven & Groenland, 1993).

1 Tulisan ini merupakan bagian dari disertasi yang diajukan penulis untuk mendapatkan gelar Ph.D. dari Universitas Tilburg, Belanda.

2 Korespondensi mengenai artikel ini dapat melalui: [email protected]

Consumer resources also concern time. The generic level of decision making also takes place when one is having a free time, either expectedly or unexpectedly. Examples include situations such as being stranded at a strange place due to travel chaos, cancellation of a planned appoint-ment, or free time due to earlier accomplishment of a job. One is likely to think over alternative ways of using the time, such as reading a book, window shopping, listening to favourite music, working with a notebook, or having a chat over the internet. A particularly common situation is retirement, both voluntary and involuntary retirement due to work lay off (Van Solinge, 2006). One may opt an extended summer holiday, learn a new skill, or take on a new life project such as writing a book. Such choices can be characterized in terms of utilitarian and hedonic or experiential values (e.g., Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000).

lessons. A particular interest of the generic level concerns the immediate versus long-term consequences of the alternative activities.

Life transitions often force people to make some generic level decisions. Take divorce as an example. Direct conse-quences of a divorce settlement may include changes in the amount of income, place of residence, social identity, and daily chores (Poortman, 2002). A divorce settlement often requires the divorcee to redefine life, such as whether to get married again or whether to venture a work or career (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002), and decide what lifestyle or standard of living are acceptable, and even friendship and personal network to maintain (Terhell, 2003). Decision making at a life transition represents a strategic type of the generic level of consumer decision making. It involves choices between different types of life themes and values (e.g., Huffman, Ratneshwar & Mick, 2000).

The aforementioned situations occur at the individual level. But, life transition may occur at a mass-scale, such as in the aftermath of a major natural disaster. Large scale disasters, such as the 26th

December 2004 tsunami, left the survivors unwillingly to redefine their life. Imagine the thoughts emerging within one who had just lost his wife, children and most of his family members, house and almost everything he/she had ever owned, as well as the place and tools to work. A man who I happened to encounter in Aceh, Indo-nesia, 11 days after the tsunami simply stated, I don’t know what I am going to

do with my life. This expresses a sense of

loss for one’s life goals, experienced by

many of the survivors, synonymous to a

loss in one’s meaning of life (Carballo,

Heal & Horbaty, 2006) at a mass scale.

Goals at the most general level can be equated to a generic goal. It concerns major categories of desired end states of one’s life, and may thus constitute the meaning of life itself.

In short, the generic level concerns all types of consumer resources, namely money, effort, social power, and time, including the live-time of the consumer itself. It occurs at the individual as well as at the societal levels. The mental processes are articulated when an individual is deliberating choices of activities related to a resource. The objective of the decision making is to optimize the utility or benefit for the short- and long-term interests of the consumer. The higher the value of the resources concerned, the higher the involvement in the processes of decision making. At a certain level, these processes may require one to look inward deeply, to search one’s soul, to examine faiths and fundamental values, and to contemplate what life means to the consumer.

How the generic level relates to other aspects of consumer behaviour?

spending, are the primary concerns for the consumer.

The specific, modal, and generic level all contributes to the welfare of the individual. In particular, the generic level of consumer decision making has strategic consequences. According to Thaler (1985), saving and spending represents the most important types of economic behaviour of individuals and households. Considering that decisions regarding saving and spending are taken at the generic level, many aspects of the consumers’ life are highly influenced by the processes of decision making at the generic level. For example, financial security or vulnerability of individual consumers and households are likely to be a consequence of past decision making processes at the generic level. This implies that high quality generic level decision making will signifi-cantly contribute to the well-being of indi-vidual consumers and households. The following are two cases that illustrate the strategic importance of the generic level:

Michael Carroll won £9. million in

the National Lottery in 2002. Immediately he bought four homes, a holiday villa in Spain, two convertible BMWs, two Mercedes-Benz cars, a stake in a beloved football club, spent

untold thousands on alcohol and

drugs, wears a very large amount of gold jewellery. Eighteen months after winning the lottery, all of the fortune had been spent on this extravagant

life, and now he is nearly broke

(Wikipedia)

”rad Duke, 34, pocketed a lump sum

of $85 million after winning a $220 million Powerball jackpot in 2005. He spent the first month of his new life assembling a team of financial advi-sors. The portfolio he has built: $45 million in municipal bonds, $35

million on oil and gas stocks and real estate, $18,000 repayment on student loan, $125,000 paying off mortgage. He also set $1,3 million family foundation. He spent $63,000 on a trip to Tahiti with 17 friends, $12,000 annual gift to each of his family members, and $14,500 on a hobby car. Eighteen months after wining his fortune, he is on course of his goal: to

become a billionaire in years

(CNN Money).

Scientific examination to the lottery winning phenomena are reported in Nissle and Bschor (2002), and Gardner and Oswald (2001).

Not only is this an important problem, the generic level of consumer behaviour is also a common problem. For some time now, empirical studies have revealed individual differences in the propensity to save (Wärneryd, 1999). Whereas some people routinely put aside a certain portion of their income, others fail to do so, on a regular basis, and the rest is never saving. Even among those who regularly save, many are doing so for amounts that are too small or in times that are too late. A survey shows that when people get older, they usually regret their lower savings: 60 per cent wish they had saved more when they were younger (BMRB International, 1994). In retrospect, older people often regretted their late start on pension savings (Prudential UK, 1996). As evident in the survey, 42% of the respondents agreed to the statement: I wish I had considered my pension arrangement

earlier. This is at odds with the common

made by Katona (1975, p. 235), that is,

plans to save often represent good

intentions that are not carried out at a later

date.

Saving is not only a problem at the individual or household level. At the macroeconomic level, low saving rates have become problems in many developed countries. For example, the Financial Research Survey (1996) reports that 26 per-cent of the UK labour force has no saving or financial investment at all. Of it, 22 and 21 percent are among those aged 45-54 and 55-64 years, respectively. Thirty three per cent of the former group and 26% of the latter have less than £500 in their current saving and investment accounts. Further-more, 40 percent of working adults inade-quately contribute to their pension. Should these current trends continue, it will pay out less than 40 per cent of their final salary.

Under-saving represents another side of consumer problems, namely over spending. It has become both individual and societal problems (e.g., Schor, 2000). Various explanations have been offered. Among others, the urge to conspicuous consumption, an explanation offered by Thorsten Veblen dated back to the late 19th

century (Veblen, 1899/2000). Another explanation is concerned with the desire to keep up with the Jones’s (Duesenberry, 1949). With the advent of the new era of consumerism, mediated by the high penetration of television, it causes the up-scaling of consumer aspirations, spending, and norms (e.g., Schor, 2000).

Both facets of the problem may originate at the generic level of consumer behaviour. That is, the failure to identify goals that include needs and wants at present time and in the future, and the failure to budget current and future income accordingly. Another problem is

concerned with the failure of self-control with regard to prior budget commitment (Shefrin & Thaler, 1988). Self-control is often discussed outside the area of the generic level of consumer behaviour. However, there is no point in self-control if there is no prior budget commitment, which is conceptually determined at the generic level. Moreover, self-control may increase or decrease with the clarity of budget commitment (Baumeister, Heatherton, & Tice, 1994).

Toward this end, studying the generic level of consumer behaviour is relevant to economic psychology, government policy, and everyday practice. For the economic psychologist, the study may advance knowledge of consumer behaviour. For consumers, it is a way to understand their behaviour as well as a means to improve the direction towards a more goal-directed behaviour. To policy makers, it may increase the accuracy of welfare policy and planning. This is important in the context of problems regarding household saving in many developed economies. To mar-keters, it is relevant for marketing pro-ducts in the strategic domain of consumer behaviour.

Theoretical approaches to generic level

have been a subject of discussion (e.g., Hogarth & Reder, 1986; Earl, 1990; Lopes, 1994; Lunt, 1996; Van Raaij, 1999; Wärneryd, 1999). Perspectives of each of the approaches will be summarized in the following three sections.

Economic approach

A generic allocation problem is at the heart of the economic discipline. It is defined as a study regarding how an economy or individual chooses to allocate scarce resources to different uses and over time (Samuelson & Nordhaus, 1992). The objective of an economic study is to make predictions and to provide recommen-dations. The fundamental assumption is that economic agents (individuals, firms, or nations) are rational and act rationally. It means they attempt to maximize their utilities or profits from they way they allocate their resources. Furthermore, interactions between rational agents with rational expectations create a market that enforces agents to behave rationally. Market forces will eliminate irrational agents through processes of profit taking by rational agents. Thus, the theory assumes perfect competition on the side of the market. These two assumptions are obviously very strong and it is unlikely that they withstand empirical examina-tion. Nevertheless, they may serve useful analytical objectives (Kirzner, 1997). It does not matter whether the assumption does not correspond to reality, as long as the theory provides useful predictions. Friedman (1953) suggests an eloquent analogy of economic theory to an expert billiard player. In his words:

It seems not at all unreasonable that

excellent predictions would be yielded by the hypothesis that the billiard player made his shots as if he knew the complicated mathematical

for-mulas that would give the optimum directions of travel, could estimate

accurately by eye the angles, etc., ….

could make lightning calculations from the formulas, and could then make the balls travel in the direction

indicated by the formulas. p. .

In reality it is obvious that very few expert billiard players, if any at all, are well versed with mathematics and physics to match their expertise. It is not necessary to master mathematics and physics in order to become an expert billiard player, as it is not necessarily true that every economic agent is indeed perfectly rational and every market is perfectly competitive. Rationality and market competition are approximations for the way economic agents are interacting and market mecha-nisms are developing.

Consumer resources will be saved when consumption out of it has reached its optimum utility.

The principle may be extended to include inter-temporal concerns of con-sumption. Maximum utility can be obtained by distributing consumption of a resource over a period of time. A unit of consumption gives higher level of satisfaction after a certain period of time, as compared to the consumption of the same unit right after previous consump-tion. Thus, a rational consumer is assumed to weigh the marginal utility derived from consumption now to that of the future. Saving is a mechanism to smoothen con-sumption over time, so as to maximize utility over the period. Important theories in applying this principle are the life-cycle theory (Modigliani & Brumberg, 1954; Modigliani, 1986) and permanent income theory (Friedman, 1957). The gist of these theories is illustrated eloquently in Thaler (1994):

How much should … a person

consume in a given year? The answer is this: in any year, compute the present value of financial wealth, including current income, net assets, and the expected value of future income; figure out the level annuity that could be purchased with that money; then consume the amount that would be received from such an

annuity pp. -108).

From this brief overview, it can be concluded that economic theories focus on prediction and prescription. The theoreti-cal approach is based on assumption of rationality of the economic agent. Al-though the assumption has been defended as acquiring descriptive power, it is more appropriately conceived as a normative assumption (e.g., Thaler, 1980). A highly relevant assumption to the generic

allo-cation level of consumer behaviour is that consumption is preferred to saving. Thus, saving is what is left over from consump-tion (Lea, Tarpy, & Webley, 1987). This definition signifies the residual nature of saving, against which Katona (1975) shows other types of saving, namely discretio-nary and contractual savings. Moreover, extensive empirical studies have consis-tently identified several saving motives, namely precautionary, transactional, spe-culative, retirement, and inter vivo and bequest saving motives (Katona, 1975; Nyhus, 2002). Within the policy domain, the primary saving models (e.g., the life-cycle model, the precautionary savings model, the bequest motive model) have not been successful in explaining why so many elderly reach retirement with little or no savings (Gustman & Juster, 1996; Poterba, 1996).

Behavioural approach

expend-itures (Thaler, 1999). An important mental accounting practice in financial behaviour is that income and wealth are organized in separate mental accounts that implies differential marginal propensity to con-sume different sizes of income, namely current income account, current asset accounts, and future income account (Shefrin & Thaler, 1988). The behavioural approach to consumer behaviour assumes fundamental problems in terms of bounded rationality, bounded willpower, and bounded self-control (Mulainathan & Thaler, 2000; Thaler, 2000; Jolls, Sunstein, & Thaler, 1998).

In mental accounting, expenditures are grouped into categories (housing, food, clothing, etc.). Similarly, wealth is assigned in one of the three mental accounts, namely current income account, current asset account, and future income account. Expenditures are financed from money drawn from corresponding accounts. For example, money deducted from current income account is for spending on food and entertainment, whereas home impro-vement is financed from current asset accounts. Each mental account is asso-ciated with a different propensity to save and to spend. Specifically, the current income is almost completely spent whe-reas future income is not at all consumed. The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) current assets is in between the MPC of current income and the MPC of future income.

Mental accounting also implies that money is not fungible. That is, money in a mental account is not a perfect substitute for money in another mental account (Thaler, 1999). Henderson and Peterson (1992) offer a cognitive psychological interpretation of mental accounting. They argue that the framing processes under-lying mental accounting are the same as

the processes described in categorization, schema, and script theories. Thus they suggest the use of existing theories when attempting to explain mental accounting processes.

Another important feature of the BLCH concerns modelling consumer efforts for establishing self-control. The model is based on the assumption of two competing functions in the consumer, namely the planner and the doer (Thaler & Shefrin, 1981). The planner is always trying to secure long-term interest of the con-sumer, whilst the doer is pathologically myopic. The latter tempts consumers to spend income as soon as possible. Exer-cising control over the power of the doer is assumed to require willpower effort, which implies negative utility for the consumer. Mental accounting is viewed as a way for exercising self-control. In addi-tion, pre-commitment devices such as a contractual obligation to save, similar as the notion of contractual saving (Katona, 1975), are viewed as devices to help exer-cise self-control.

having already been substantiated (Thaler & Bernartzi, 2004). Subsequently, recom-mendations based on BLCH have been applied to national pension policies in several developed countries, such as the USA, the UK, and New Zealand (The Economist, 2005).

Although the behavioural approach to consumer behaviour adopts more realistic assumptions regarding human behaviour, the focus of the research remains the same as mainstream economics, namely predic-tion. Contrary to the mainstream theories, BLCH reflects the limitations of human capacities, particularly with regards to problems of self-control, and are thus substantially closer to capturing the reality in consumer behaviour. Nevertheless, it is taken for granted that individuals assign their income and wealth into a number of budgets. Questions such as how budget categories are formed, for what purpose, where the purposes come from, and how the source of a purpose may affect the ability to self-control, are not addressed in BLCH. For this, we may say that the theory has missed another quality of human being, namely the capacity for self-regulation (Bandura, 2001). Further Bandura (2001) argues that the unparallel success of human beings in evolutionary history did not materialize without the capacity for self-regulation of human thought and action. It is plausible to assume that consumer behaviour is self-regulated, especially at the generic level when a consumer is considering ways of utilizing resources at his or her disposal.

Psychological approach

Psychological research is concerned with describing the behaviour and the processes underlying the behaviour. Theo-ries are developed on the basis of empiri-cal observations through various

experi-mental and survey methods. The theories accommodate several factors, namely internal factors (i.e., personality, motiva-tion, attitude), psychological processes (i.e., cognitive and affective processes), and external factors (i.e., stimuli, context) in the explanation of the behaviour.

One of major theoretical approach in psychology is the social cognitive theory. The most complete version of the theory was introduced by Bandura (1986). Among others, the theory assumes the capacity of human agency. It reflects the essence of being human as the capacity to exercise control over the nature and quality of

one’s life. These capacities are achieved

through functional capabilities of human agency, namely intentionality, fore-thought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflecti-veness. These capacities enable human being to self-regulate their behaviour.

and unconscious processes. Thus, self-regulation provides a framework on how the self is put together in behaviour in many contexts of human life.

Many theories of self-regulation have been proposed. There are theories that specifically address the basic processes of self-regulation (e.g., Carver & Scheier, 1981; Mischel & Ayduk, 2004; Cervone, 2004), aspects of self-regulation processes (e.g., Banfield et al., 2004), developments

of individual’s capacity for self-regulation

(Vohs & Ciarocco, 2004), interpersonal components of self-regulation (Leary, 2004), and individual differences in self-regulation (Barkley, 2004). In applied settings, consequences of self-regulation have been studied quite extensively in areas such as addictive behaviour (Bechara, 2006; Sayette, 2006; Hull & Slone, 2006) and consumer behaviour (Faber & Vohs, 2004). Albeit such diversities, there are two basic properties shared by all theories of self-regulation (Cameron & Leventhal, 2003). The first concerns the construal of self-regulation as a dynamic motivational system of setting goals, deve-loping and enacting strategies to achieve those goals, appraising progress, and revising goals and strategies accordingly. The other property relates to the manage-ment of emotional responses as crucial elements of the motivational system.

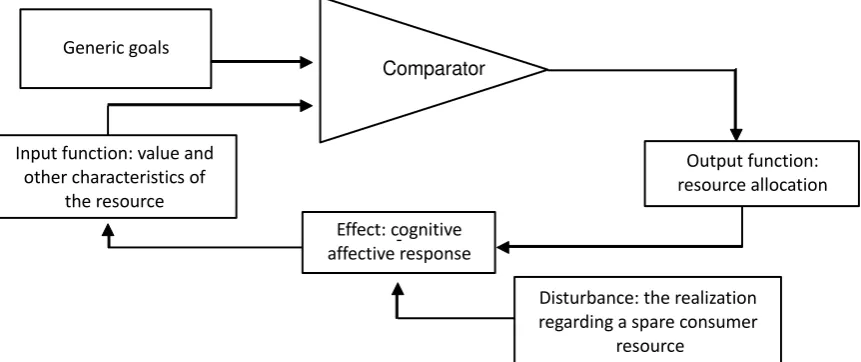

The cybernetic control theory (Carver & Scheier, 1981; Scheier & Carver, 1988; Carver, 2004) provides a succinct expla-nation of the dynamic motivational setting. The theory views individuals’ behaviours as a continuous process of movement toward (and sometimes away from) goals. The self-regulatory mecha-nisms ensure that feedback loops are present in the continuous movement. A feedback loop consists of four components, namely input function, reference value

(goals, standards), comparator, and output function (Carver, 2004). The process is analogous to the mechanism of a ther-mostat: sensors detect the temperature of the room (input function), the comparator compares the measured temperature with the predetermined (goals, standard) desired temperature, the heating or cool-ing mechanism is activated (output func-tion). Figure 1. summarises the theory in the context of generic level of consumer behaviour.

It is obvious that goals are primary components of self-regulatory mechan-isms. Fisbach, Dhar and Zhang (2006) state that setting goals and monitoring progress towards goal achievement are fundamen-tal to theories of self-regulation. Goals concerns any type of desired states that individuals possess, such as personal striving (Emmons, 1989), possible selves (Markus & Nurius, 1986), and self-guide (Higgins, 1996). Goals can be understood from its conceptual construction, i.e., structural properties, goal processes, and goal contents (Austin & Vancouver, 1996; Pervin, 1989; Kruglanski et al., 2002). The functions of goals are to energize and direct behaviour (Kruglanski et al., 2002). Besides, in the self-regulation mechanisms, goals serve as reference values in feedback loops.

S.C. Grunert, 1995). Based on Austin and Vancouver (1996), and Bagozzi, Bergami and Leone (2003), generic goals are inhe-rent in the self-regulatory mechanisms of the consumer, and simply lying dormant until they are made salient by relevant stimuli. The self-regulatory mechanism in the context of generic decision making regarding a windfall income can be ex-plained as follows. The presence of wind-fall income enlightens the consumer on opportunities of achieving goals. The self-regulation processes starts with the com-parison between the characteristics of the windfall income, i.e., the size and the source (Henderson & Peterson, 1992), and the state of goals that become active. Deci-sions regarding allocations of the money into generic-level budgets, i.e., spending and saving, follow from the comparison processes. The mental accounting processes of the decision making (Thaler, 1980, 1985, 1999) implies that there are dif-ferences in the marginal propensity to consume the same amount of incomes but of different characteristics of sources. Thus a self-regulation approach predicts differ-ent behaviours of a windfall income as compared to the economic approach, and

different explanations of the same types of behaviour as compared to the behavioural approach. In addition, the self-regulatory approach focuses on the explanation of processes, whereas the economic and be-havioural approaches focus on the out-come of behaviour. Generic goal systems constitute one of the psychological con-structs in the self-regulation of consumer behaviour at the generic level.

Way forward

Our review so far favours the social cognitive approach to consumer behaviour at the generic level. Further, the preceding section concludes with a hypothetical generic goal system as a necessary psycho-logical construct in consumer behaviours at this level. This hypothesis reflects a top-down view, i.e., consumer behaviours that are goal-driven (e.g., Paulssen & Bagozzi, 2005; Park & Smith, 1989; Bettman, Luce, & Payne, 1998), in contrast to the bottom-up view, i.e., consumer behaviours that are product-driven (e.g.,Johnson, 1984, 1988). To the best of our knowledge, there is no effort yet at examining what goals constitute a generic goal system, how these goals are organized, and how generic goal

Generic goals

Input function: value and other characteristics of

the resource

Output function: resource allocation

Disturbance: the realization regarding a spare consumer

resource Effect: cognitive

affective response-

Comparator

Figure 1. Schematic depiction of a feedback loop of a cybernetic control in a generic

systems explain differences in consumer behaviour at the generic level. Therefore this section attempts to higlight way forwards in consumer behaviour research with a focus on eliciting, constructing, and applying the generic goal systems in the explanation of consumer decision making. The specific research questions can be described as follow.

What is the appropriate method and procedure for eliciting generic goals and its organiza-tional properties?

As discussed above, a generic goal system comprises multiple goal contents that are organized in certain ways. In addition, there might be individual diffe-rences in the generic goal systems. Differ-ences between individuals may be cha-racterized in terms of different contents of the generic goal system, or it might be in terms of different organization of the same goal contents, or a combination of content and organization of the generic goal sys-tem. Following on this rationale, a focus

on eliciting the subject’s goals and how

these goals are interrelated are more appropriate for the purposes of this study, rather than focusing on measuring how strongly the subjects are committed to certain goals. Whereas goal elicitation implies an idiographic approach, which is more suitable for taping into a subjective construct, such as consumer goal systems, measurements using psychological scales are more appropriate for testing a hypo-thesis concerning a predetermined psy-chological construct (Gravetter & Forzano, 2006).

Among the goal elicitation methods, the laddering technique has gained wide acceptance as a method that satisfies such a requirement. Other methods include projective techniques (McClelland, 1961; Malhotra & Peterson, 2006). Several

varia-tions in the laddering technique have been developed, such as the laddering tech-nique for eliciting the means-end chain of consumer consumption (Reynolds & Gutman, 1988), for eliciting superordinate goals (Pieters, Baumgartner, & Allen, 1995; Bagozzi, Bergami, & Leone, 2003), and for eliciting personal values in organizational contexts (Bourne & Jenkins, 2005). How-ever, these methods were designed for eli-citing consumer goal systems at more spe-cific levels. For example, the means-end chain model is concerned with goals in the context of choice between brands in a product category. On the other hand, the superordinate goal laddering procedure is concerned with specific focal goals that may signify choices between modal beha-viours. A generic allocational context involves categories of consumer behaviour such as spending, saving, investing, and repaying debt. Empirical work on this area of study should attempts to answer is what specific aspects of the laddering pro-cedure are required for eliciting generic goals and its organizational properties.

What are the generic goals and how are they organized?

to keep up with the Jones’s Duesenberry,

1949; Schor, 2000). Different types of sav-ing motives such as explained in Keynes (1936/1964), Browning and Lusardi (1996), and Katona (1975) also appear to fit in the generic goal system. Goals at the generic level may represent what consumers express as needs, wants, desires, motives, and values (e.g., Belk, Ger, & Askegaard, 2000; Rokeach, 1973; Schiffman & Kanuk, 2004; Maslow, 1954), especially with re-gard to consumption motives. The prob-lem studies on this area should attempt to address is, among others, how these goals are organized in the generic goal systems.

Research demonstrates that individu-als have to spend higher efforts when multiple goals are salient at the same time (Bettman, Luce, & Payne, 1998). The rela-tionships between the salient goals can be characterized in terms of either substitu-tive, complementary, or competing (Kruglanski et al., 2002). Higher cognitive-motivational processing is required when multiple goals are incompatible to each other (Jain & Maheswaran, 2000). In this regard, saving and spending goals are naturally competing (Katona, 1975), since what is saved cannot be spent, and vice versa. Because the generic level of con-sumer behaviour involves spending and saving goals (Van Veldhoven & Groenland, 1993; Antonides & Van Raaij, 1998), and because goal organization faci-litates individual functioning in the con-text of the salience of multiple goals (Kruglanski et al., 2002), this study as-sumes that goals at the generic level are structured in certain fashion. The problem that we should be focused on is how ge-neric consumer goals are organized, what are the organizational properties, and to which degrees are generic goals indepen-dent and interdepenindepen-dent of each other.

What factors determine the formation of ge-neric goal systems?

Evidence of individual differences in consumer behaviour is paramount. Almost every handbook in consumer behaviour, e.g., Antonides and Van Raaij (1998), Assael (1992), Schiffman and Kanuk (2004), spent a chapter on the topic of individual differences. In the financial domain, Wärneryd (1999) describe consu-mers of the same income levels, life-cycle stages, and demographic backgrounds as often different to each other with regards to their wealth and financial preparedness in retirement. Wealth and pensions are the direct results of retirement planning (Selnow, 2004), which involves decision makings at the generic level. Given that consumer decision making is goal-driven (Van Oesselaer, 2006), we should expect that individual differences in the wealth and pension levels are influenced by dif-ferences in the generic goal systems. The question any research in this areas should like to answer is what are the psychologi-cal and demographic factors that deter-mine differences in the generic goal sys-tems of individuals.

References

Antonides, G., & Van Raaij, W. F. (1998).

Consumer behaviour: A European pers-pective. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Assael, H. (1992). Consumer behavior and marketing action (4th ed.). Boston:

PWS-Kent.

Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Struc-ture, process, and content. Psychologi-cal Bulletin, 120, 338-375.

motives in goal setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 915-943.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 521-526.

Banfield, J. F., Wyland, C. L., Macrae, C. N., Münte, T. F., & Heatherton, T. F. (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation. In R.F. Baumeister & K.D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applica-tions (pp. 62-83). New York: Guildford Press.

Barberis, N., & Thaler, R. (2003). A survey of behavioral finance. In G.M. Constantinides, M. Harris, & R. Stulz (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of finance (pp. 1051-1121). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Barkley, R. A. (2004). Attention-defi-cit/hyperactivity disorder and self-regulation. In R.F. Baumeister & K.D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 301-323). New York: Guildford Press. Baron, J. (2000). Thinking and deciding.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univer-sity Press.

Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (1994). Losing control: How and why people fail at self-regulation. San Diego: Academic Press.

Bechara, A. (2006). Broken willpower: Impaired mechanisms of decision making and impulse control in sub-stance abuse. In N. Sebanz & W. Prinz (Eds.), Disorders of volition (pp. 399-418).London: Bradford Books.

Belk, R. W., Ger, G., & Askegaard, S. (2000). The missing streetcar named desire. In S. Ratneshwar, D.G. Mick, & C. Huffman (Eds.), The why of consump-tion: Contemporary perspectives on con-sumer motives, goals, and desires (pp. 98-119).London: Routledge.

Bettman, J. R., Luce, M. F., & Payne, J. W. (1998). Constructive consumer choice processes. Journal of Consumer Research,

25, 187-217.

Bourne, H., & Jenkins, M. (2005). Eliciting

managers’ personal values: “n adap

-tation of the laddering interview me-thod. Organizational Research Methods, 8, 410-428.

Browning, M., & Lusardi, A. (1996). Household saving: Micro theories and micro facts. Journal of Economic Litera-ture, 34, 1797-1855.

Cameron, L. D., & Leventhal, H. (2003). Self-regulation, health and illness: An overview. In L.D. Cameron & H. Leventhal (Eds.), The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour (pp. 1-13). London: Routledge.

Caprara, G. V., & Cervone, D. (2000). Per-sonality: Determinants, Dynamics, and Potentials. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Carballo, M., Heal, B., & Horbay, G. (2006). Impact of the tsunami on psychosocial health and well-being. International Review of Psychiatry, 18, 217-223.

Carver, C. S. (2003). Self-regulation. In A. Tesser & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Backwell handbook of social psychology: Intraindi-vidual processes (pp. 307-328). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing

applica-tions (pp. 13-39). New York: The Guildford.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M.F. (1981). Atten-tion and Self-RegulaAtten-tion: A Control-Theory Approach to Human Behavior.

New York: Springer-Verlag.

Cervone, D. (2004). The architecture of personality. Psychological Review, 111,

183-204.

Dhar, R., & Wertenbroch, K. (2000). Con-sumer choice between hedonic and utilitarian goods. Journal of Marketing Research, 37, 60-71

Duesenberry, J. S. (1949). Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Earl, P. E. (1990). Economics and psycho-logy: A survey. The Economic Journal, 100, 718 – 755.

Emmons, R. A. (1986). Personal strivings: An approach to personality and sub-jective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1058-1068. Faber, R. J., & Vohs, K. D. (2004). To buy or

not to buy? Self-control and self-regu-latory failure in purchase behavior. In R.F. Baumeister & K.D. Vohs (Eds),

Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 509-524). New York: The Guildford.

Fisbach, A., Dhar, R., & Zhang, Y. (2006). Sub-goals as substitutes or comple-ments: The role of goal accessibility.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychol-ogy, 91, 232-242.

Friedman, M. (1953). Choice, chance, and the personal distribution of income.

The Journal of Political Economy, 61, 277-290.

Friedman, M. (1957). A theory of the con-sumption function. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gardner, J., & Oswald, A. (2001). Does money buy happiness? A longitudinal study using data on windfalls. Retrieved January 26, 2009, from http: //www. warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/Economics/osw ald/marchwindfalls.GO.pdf.

Gravetter, F. J., & Forzano, L-A. B. (2006).

Research methods for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Belmont: CA:

Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. Grunert, K. G., & Grunert, S.C. (1995).

Measuring subjective meaning structures by the laddering method: Theoretical considerations and metho-dological problems. International Jour-nal of Research in Marketing, 12, 209-225.

Gustman, A .L, & Juster, F. T. (1996). In-come and wealth of older American households: Modeling issues for pub-lic popub-licy analysis. In E.A. Hanushek & N.L. Maritato (Eds.), Assessing know-ledge of retirement behavior (pp. 11-60). Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Henderson, P. W., & Peterson, R. A. (1992). Mental accounting and categorization.

Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 51, 92-117.

Hetherington, E. M., & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company. Higgins, E. T. 99 . The self-digest :

Self-knowledge serving self-regulatory functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 1062-1083.

Hogarth, R. M., & Reder, M. W. (1986). Perspectives from economics and psy-chology. The Journal of Business, 59,

S185-S207.

Ratneshwar, D.G., Mick, & C. Huffman (Eds.), The why of consump-tion (pp. 9-35).London: Routledge. Hull, J. G., & Slone, L. B. (2006). A

dy-namic model of the will with an appli-cation to alcohol-intoxicated behavior. In N.Sebanz & W. Prinz (Eds.), Disord-ers of Volition (pp.439-455). London: Bradford Book.

Jain, S. P., & Maheswaran, D. (2000). Moti-vated reasoning: A depth-of-processing perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 26, 358-371.

Johnson, M. D. (1984). Consumer choice strategies for comparing noncompara-ble alternatives. Journal of Consumer Research, 11, 741-753.

Johnson, M. D. (1988). Comparability and hierarchical processing in multialter-native choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 303-314.

Jolls, C., Sunstein, C. R., & Thaler, R. (1998). A behavioral approach to law and economics. Stanford Law Review, 50, 1471-1550.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist, 39, 341 – 350.

Karoly, P. (1993). Mechanisms of self-regulation: A systems view. Annual Review of Psychology, 44, 23-52.

Katona, G. (1975). Psychological economics.

New York: Elsevier.

Keynes, J. M. (1936/1964). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. San Diego: Harcourt.

Kirzner, I. M. (1997). Entrepreneurial dis-covery and the competitive market process: An Austrian Approach. Jour-nal of Economic Literature, 35, 60-85. Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, J.Y., Fishbach, A.,

Friedman, R., Chun, W.Y., & Sleeth-Keppler, D. (2002). A theory of goal

systems. Advances in experimental social psychology, 34, 331-378.

Kunda, Z. (1999). Social cognition: Making sense of people. Cambridge, MA: MIT Lea, S. E. G., Tarpy, R. M., & Webley, P.

(1987). The individual in the economy.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univer-sity Press.

Leary, M. R. (2004). The function of self-esteem in terror management theory and sociometer theory: Comment on Pyszczynski et al. (2004). Psychological Bulletin, 130, 478-482.

Lopes, L. L. (1994). Psychology and eco-nomics: Perspectives on risk, coopera-tion, and the marketplace. Annual Review of Psychology, 44, 197-227.

Lunt, P. (1996). Rethinking the relationship between economics and psychology.

Journal of Economic Psychology, 17, 275-287.

Malhotra, N. K., & Peterson, M. (2006).

Basic marketing research: A decision-making approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41, 954-969.

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and perso-nality. New York: Harper & Row. McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving

society. Princeton, MA: Van Nostrand. Miscel, W., & Ayduk, O. (2004). Willpower

in a cognitive-affective processing system. In R.F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 99-129).New York: The Guildford. Modigliani, F. (1986). Life cycle, individual

Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function. An interpretation of cross-section data. In K.K. Kurihara (Ed.),

Post-Keynesian economics (pp. 388-438). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univer-sity Press.

Mullainathan, S., & Thaler, R. H. (2000). Behavioral economics. National Bu-reau of Economic Research. Working Paper 7948. Retrieved November 17, 2001, from http://www.nber.org/ papers/w7948.

Nissle, S., & Bschor, T. (2002). Winning the jackpot and depression: Money cannot buy happiness. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 6, 183-186.

Nyhus, E. K. (2002). Psychological determi-nants of household saving behavior.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration, Norway. Park, C. W., & Smith, D. C. (1989).

Product-level choice: A top-down or bottom-up process? Journal of Con-sumer Research, 16, 289-299.

Paulssen, M, & Bagozzi, R. P. (2005). A Self-regulatory model of consideration set formation. Psychology and Market-ing, 22, 785-812.

Pervin, L. A. (Ed.). (1989). Goal concepts in Personality and Social Psychology.

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pieters, R., Baumgartner, H., & Allen, D. (1995). A means-end chain approach to consumer goal structures. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 12, 227-244.

Poortman, A-R. (2002). Socioeconomic causes and consequences of divorce. Unpub-lished doctoral dissertation, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Poterba, J. M. (1996, July). Demographic structure and the political economy of public education. NBER Working Paper No.W5677. Retrieved February 2, from http://www.nber.org/papers/ w5677.

Reynolds, T. J., & Gutman, J. (1988). Lad-dering theory, method, analysis and interpretation. Journal of Advertising Research, 28 (February/March), 11-31. Rokeach, M. (1973). The Nature of Human

Values. London: The Free Press.

Samuelson, P. A., & Nordhaus, W.D. (1992). Economics (14th ed.). New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Sayette, M. A. (2004). Craving, cognition, and the self-regulation of cigarette smoking. In N.Sebanz & W. Prinz (Eds.), Disorders of volition (pp. 419-437).London: Bradford Book.

Schiffman, L. G., & Kanuk, L. L. (2004). Consumer behavior (8th ed.). Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Schor, J. B. (2000). Towards a new politics of consumption. In J.B. Schor & D.B. Holt (Eds.), The consumer society (pp. 446-462).New York: New Press. Selnow, G. W. (2004). Motivating

retire-ment planning: Problems and solu-tions. In O.S. Mitchell & S.P. Utkus (Eds.), Pension design and structure: New lessons from behavioral finance (pp. 43-51). New York: Oxford University Press.

Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1988). The behavioural life-cycle hypothesis. Eco-nomic Inquiry, 26, 609-643.

Thaler, R. H. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 1,

Thaler, R. H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4, 199-214.

Thaler, R. H. (1994). Psychology and sav-ings policies. The American Economic Review, 84, 186-192.

Thaler, R. H. (1999). Mental accounting matters. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12, 183 – 206.

Thaler, R. H. (2000). From homo econo-micus to homo sapiens. Journal of Eco-nomic Perspectives,14, 133 – 141.

Thaler, R. H., & Benartzi, S. (2004). Save More TomorrowTM: Using behavioural

economics to increase employee sav-ing. Journal of Political Economi,112,

S164-S187.

Thaler, R. H., & Shefrin, H. M. (1981). An economic theory of self-control. Journal of Political Economy, 89, 392-406.

Terhell, L. (2003). Changes in the personal network after divorce. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Tilburg, The Netherlands.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychol-ogy of choice. Science, 211, 453-458. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1986).

Ra-tional choice and the framing deci-sions. Journal of Business, 59, 5251 – 5278.

Van Oesselaer, S. J., Ramanathan, S., Campbell, M. C., Cohen, J. B., Dale, J. K., Janiszewski, C., et al. (2005). Choice based on goals. Marketing Letters, 16,

335-346.

Van Raaij, W. F. (1999). Economic psychol-ogy between psycholpsychol-ogy and eco-nomics: An Introduction. Applied Psy-chology: An International Review, 48,

263-272.

Van Solinge, H. (2006). Changing tracks: Studies on life after early retirement in the

Netherlands. Unpublished doctorate

dissertation, The Netherlands Interdis-ciplinary Demographic Institute, The Hague.

Van Veldhoven, G. M., & Groenland, E. A. G. (1993). Exploring saving behaviour: A framework and a research agenda.

Journal of Economic Psychology, 14, 507-522.

Veblen, T. (1899/2000). Conspicuous con-sumption. In J.B. Schor & D.B. Holt (Eds.), The consumer society (pp. 187-204).New York: New Press.

Vohs, K. D., & Ciarocco, N. J. (2004). Inter-personal functioning requires self-regulation. In R.F. Baumeister & K.D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 392-410). New York: Guildford Press. Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2004).

Understanding self-regulation: An introduction. In R.F. Baumeister & K.D. Vohs (Eds), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applica-tions (pp. 1-9). New York: The Guild-ford.

Wärneryd, K. E. (1999). The psychology of saving: A study on economic psychology.