Auditor decision-making in different

litigation environments: The Private

Securities Litigation Reform Act,

audit reports and audit firm size

Marshall A. Geiger

a,*, K. Raghunandan

b,

Dasaratha V. Rama

baDepartment of Accounting, University of Richmond, 1 Gateway Road, Richmond, VA 23173, United States

bDepartment of Accounting, Florida International University, United States

Abstract

The adoption of thePrivate Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995had a marked impact on public accounting firms in the US by significantly reducing their liability exposure with respect to litigation involving publicly traded audit clients. This shift in the litigation environment of public accounting firms has been argued to have been manifest in changed auditor decisions regarding their audit clients. While this tort reform legislation was intended to benefit all audit firms, recent research suggests that it may have differentially affected auditors based on audit firm size. In this study, we examine the impact of the change in litigation environment ushered in by thePrivate Securities Litigation Reform Actand Big 6 membership on going-concern modification decisions for companies entering bankruptcy before and after the new legislation. Our findings, based on analyses of 694 financially stressed firms that entered into bankruptcy during the period 1991 to 2001, indicate that the likelihood of a going-concern modified

0278-4254/$ - see front matter Ó2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2006.03.005

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 804 287 1923; fax: +1 804 289 8878. E-mail address:mgeiger@richmond.edu(M.A. Geiger).

Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 25 (2006) 332–353

www.elsevier.com/locate/jaccpubpol Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 25 (2006) 332–353

opinion decreased significantly after thePrivate Securities Litigation Reform Act, and the change was particularly pronounced for the Big 6 audit firms. These results suggest that this important litigation reform had a significant effect on auditor decision-making, and that it had more of an effect on audit decisions of the Big 6 firms in comparison to the non-Big 6 firms.

Ó2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Private Securities Litigation Reform Act; Audit reports; Audit firm size

1. Introduction

ThePrivate Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995(hereafterReform Act) was enacted into law late in December 1995, and significantly altered the liti-gation environment for public accounting firms in the US. Some observers of the public accounting profession have argued that prior to 1995 the litigious environment faced by accounting firms was detrimental to the public account-ing profession and created a drag on economic growth (Gottlieb and Doro-show, 2002). After a concerted effort on the part of the profession, public accountants were afforded significant tort liability relief with the passage of theReform Act.

It has been argued that the Big 6 audit firms were the primary beneficiaries of the litigation relief brought forth by theReform Act, and that the effects of theReform Acton auditor decision-making may be more pronounced for the Big 6 firms than for the non-Big 6 (Johnson et al., 1995; Coffee, 2002). To examine the possible effects to different sized audit firms due to the adoption of the litigation reduction provisions of theReform Act, in this study we exam-ine whether the Reform Act produced a differential effect on the Big 6 firms compared to non-Big 6 firms with respect to final audit reporting decisions. Specifically, we examine whether the Big 6 audit firms were differentially less likely to render going-concern modified audit reports to subsequently bankrupt clients in comparison to the non-Big 6 audit firms after the enactment of the

Reform Act.

In a recent study,Lee and Mande (2003)find that the Big 6 audit firms were differentially less conservative following the enactment of the Reform Act in allowing their clients to report significantly higher income-increasing discre-tionary accruals than allowed by non-Big 6 firms for their clients after the

indirect, since they examine the accounting accruals of the audit firms’ clients. In contrast, our study provides direct evidence about the differential impact of theReform Acton auditors’ decisions by examining audit opinions.

Motivation for this research comes from the renewed focus on audit firm decision-making in recent regulatory and legislative actions (SEC, 2000, 2002; US Senate, 2002; Nelson, 2002; Tie, 2003; Williams, 2003), the sustained public interest in audit reporting on bankrupt companies (Weil, 2001; Bryan-Low, 2002; Breeden, 2002), and the continued importance of the Reform Act

to the public accounting profession (Kahn and Metcalfe, 1996; King and Sch-wartz, 1997; Chan and Pae, 1998; Latham and Linville, 1998). Examining audit firm behavior under different tort liability regimes and their reaction to national policy changes is warranted in order to assess the actual impact of these important legislative events on the affected parties, as well as assist in deriving more accurate estimates of the impact of future legislative changes on audit firms.

In this study we examine the prior audit opinions for 694 financially stressed companies that entered into bankruptcy during the period 1991 to 2001. After controlling for other audit report related factors, we find that the Big 6 firms were significantly less likely to have issued a prior going-concern modified audit opinion after theReform Actcompared to their prior reporting decisions, but we do not find a similar reduction in the propensity of non-Big 6 firms to issue a modified audit opinion in the post-Reform Actperiod. This evidence is consistent with the findings ofLee and Mande (2003), and supports the sugges-tion that while theReform Actushered in a less hostile litigation environment in the US, and even though it was beneficial for all public accounting firms auditing publicly traded clients due to its litigation reduction provisions, it was more important for, and had a greater impact on, the Big 6 audit firms in comparison to the non-Big 6 audit firms.

2. Background and hypothesis

Prior to the passage of theReform Act, the AICPA and public accounting firms repeatedly voiced their concern about the profession’s ‘‘litigation crisis’’ in the United States (e.g.,AICPA, 1992; POB, 1993, 1994; Mednick and Peck, 1994; Chenok, 1994). While this message was echoed in virtually all segments of the public accounting community, because of their dominance of the audit market for SEC registrants, the Big 6 firms were particularly prominent in their lobbying efforts to achieve changes in the litigation environment facing public accountants (e.g.,Cook et al., 1992; Berton, 1995). This focused effort on the part of the profession and the Big 6 accounting firms won the public account-ing profession important legislative relief with the adoption of theReform Act

in December 1995. Generally, theReform Actprovides litigation relief to the

public accounting profession by (a) making it more difficult for plaintiffs’ attor-neys to successfully pursue class-action litigation against auditors, and (b) replacing the joint and several liability provisions and providing for propor-tionate liability in damage awards.1Together, these changes made the litigation environment much more favorable to auditors than in the environment before the new legislation was enacted (Coffee, 2002; SEC, 2000). The enactment of theReform Act ushered in a new era of reduced liability exposure for public accounting firms.

Geiger and Raghunandan (2001) and Lee and Mande (2003) note that if auditors perceive a relationship between audit reporting and the likelihood of litigation and related costs, and perceive that the Reform Acthas reduced the costs associated with litigation against the auditors, then we would expect an association between the enactment of theReform Actand audit decisions. In the context of the current study, we would expect that auditors would be less likely to issue a going-concern modified audit report in the post-Reform Act

period than in prior periods.2Stice (1991) and Pratt and Stice (1994)find that lawsuits and litigation-related costs of auditors are significantly increased in the case of a financially stressed client, even if there is no audit failure. Further,

Carcello and Palmrose (1994) find that auditors who had issued modified reports prior to client bankruptcy had the highest dismissal rate and the lowest payouts. These findings indicate that there is a relationship between issuing a going-concern modified opinion to a financially stressed audit client and both the real and perceived litigation costs facing audit firms when a client files for bankruptcy.3

Prior researchers have argued that the Big 6 audit firms, with their larger amounts of wealth at risk in any one engagement, would stand to gain the most from a reduced litigation environment (Dye, 1993; Menon and Williams, 1994; Johnson et al., 1995; Francis and Krishnan, 1999; Raghunandan and Rama, 1999; Shu, 2000).4 Based on this conjecture, Lee and Mande (2003)

1

SeeBoyle and Knopf (1996), King and Schwartz (1997), Chan and Pae (1998) and Cloyd et al. (1998)for a detailed discussion of several of theReform Act’sliability provisions.

2 Additionally, we would expect changes in auditors’ anticipated litigation costs to also be

reflected in differential audit fees. However, audit fee data are not available during our study period.

3 Other studies (Geiger et al., 1998; Carcello and Neal, 2003) find that clients receiving initial

going-concern modified audit opinions that do not subsequently file for bankruptcy are significantly more likely to switch auditors. These prior results indicate that there are also costs to the auditor following the issuance of a modified opinion.

4 Alternatively, it can be argued that the larger portfolio of clients held by the Big 6 audit firms in

argue that the Big 6 firms had the most to gain from tort reforms and examine whether the decisions of the Big 6 audit firms were altered differently than those of non-Big 6 audit firms after the enactment of theReform Act. In their examination of levels of reported accounting accruals,Lee and Mande (2003)

find that clients of Big 6 audit firms significantly increased their levels of income-increasing discretionary accruals, but the reported levels for the non-Big 6 clients were not significantly different after the Reform Act than before. Their findings suggest that the Big 6 audit firms were significantlyless

conservative (i.e., they allowed more income-increasing accruals) than the non-Big 6 firms following the Reform Act, and conclude that there was a differentialReform Acteffect on audit firms based on size. However, as noted earlier, their assessment was based on indirectly examining audit firm decision-making by analyzing the levels of reported accruals of their audit clients, not by directly assessing audit firm decisions before and after the

Reform Act.

In examining the possible effects of the new litigation environment on audit decision-making, Geiger and Raghunandan (2001) find that audit firms, in general, issued fewer going-concern modified opinions to their stressed bank-rupt clients after theReform Actcompared to the period immediately preced-ing it. However, their analyses only examined an overall reportpreced-ing effect and did not assess whether the Reform Act differentially affected reporting decisions of the Big 6 audit firms compared to those of the non-Big 6 audit firms.

The empirical evidence reported in Lee and Mande (2003), when coupled with the findings ofGeiger and Raghunandan (2001), suggest that there would be a differential reporting effect after theReform Act for Big 6 and non-Big 6 audit firms. More specifically, we would expect that a reduced litigation envi-ronment would cause public accounting firms to adopt a less conservative reporting posture than might have been required in the litigation environment prior to theReform Act. This in turn would result in a reduction in the likeli-hood of issuing a going-concern modified audit opinion, and that this effect would be more salient for the Big 6 audit firms than for the non-Big 6 audit firms. The change in reporting decisions would, in turn, lead to fewer audit reports being modified for going-concern prior to a client’s bankruptcy filing for the Big 6 audit firms compared to the non-Big 6 firms.

Accordingly, in this study we directly assess the effect of a litigation reduc-tion on different sized audit firm decision-making by examining audit firm reporting decisions before and after the adoption of this important tort reform legislation. Thus, the hypothesis examined in this study is

HA. Big 6 audit firms exhibit larger reductions in the propensity to issue a going-concern modified audit report after the enactment of the Reform Act compared to non-Big 6 audit firms.

3. Research method and data

To assess the potential impact of the Reform Acton Big 6 and non-Big 6 audit firm reporting decisions, we examine audit opinions immediately prior to the client company filing for bankruptcy. Consistent with prior research, we use bankruptcy filing as clear indication of company failure, and a case where the auditor would have been expected to have issued a going-concern modified opinion in the prior period (McKeown et al., 1991b). We then exam-ine differences in prior going-concern report modification propensities of Big 6 and non-Big 6 firms both before and after the Reform Act. We use the multi-variate logistic regression model used byGeiger and Raghunandan (2001)that controls for variables shown in prior research to be associated with auditor going-concern modification reporting decisions (Chen and Church, 1992; Hop-wood et al., 1989, 1994; Raghunandan and Rama, 1995; Carcello et al., 1997). The type of audit report immediately preceding bankruptcy is the dependent variable in our model. We also include a BIG6 indicator variable in our model in order to control for general audit firm size on reporting decisions. Further, following Lee and Mande (2003), we use two interaction variables (TIME * BIG6 and TIME * NBIG6). The TIME * BIG6 variable has a value of 1 for Big 6 firms after the Reform Act, 0 otherwise. The TIME * NBIG6 variable has a value of 1 for non-Big 6 firms after theReform Act, 0 otherwise. Inclusion of these two interaction terms enables us to simultaneously capture the

post-Reform Actdifferential reporting effect for the two sizes of audit firms. TheReform Actwas signed into law on December 22, 1995, however, Title III of theReform Actpertaining to fraud and disclosures indicates that the law was effective for fiscal years beginning on or after January 1, 1996. Accord-ingly, we identify audit reports for fiscal years beginning on or after January 1, 1996 to be in the post-Reform Actperiod.5We also exclude audit reports issued prior to 1990, the effective date of SAS No. 59 (AICPA, 1988), in order to control for different reporting formats (‘‘qualified’’ versus ‘‘modified unqual-ified’’) under the different reporting standards.

McKeown et al. (1991a) and Hopwood et al. (1994) illustrate the impor-tance of separately analyzing stressed and non-stressed companies in the con-text of examining bankruptcies and prior audit opinions.6FollowingHopwood et al. (1994), we define a company as stressed if it exhibited at least one of the following financial stress signals: (a) negative working capital, (b) a loss from

5 As discussed in Section4.1, modifying the date used to identify pre- and post-Reform Acttime

periods does not substantively affect the results.

6 McKeown et al. (1991a)note that bankruptcy filings for non-stressed companies often involve

operations in any of the three years prior to bankruptcy, (c) negative retained earnings three years prior to bankruptcy, and (d) a bottom line loss in any of the three years prior to bankruptcy.

The relationship between bankruptcy, audit firm size and theReform Actis examined using a logistic regression to estimate the coefficients in the following model:

GC =a+b1LNSL +b2PROB +b3DFT +b4BKTLAG +b5REPLAG

+b6BIG6 + b7TIME * BIG6 +b8TIME * NBIG6

where

GC = 1 if opinion prior to bankruptcy was modified for going-concern, else 0,

LNSL = Natural log of sales (in thousands of dollars) deflated to 1990 levels,7

PROB = Probability of bankruptcy, as calculated from Zmijewski (1984),8 DFT = 1 if the company is in payment or technical default, else 0,9 BKTLAG = number of days from audit report date to bankruptcy date, REPLAG = number of days from fiscal year end to audit report date, BIG6 = 1 if audited by a Big 6 audit firm, else 0,

TIME * BIG6 = 1 if post-Reform Actand audited by a Big 6 audit firm, else 0, and

TIME * NBIG6 = 1 if post-Reform Actand audited by a non-Big 6 audit firm, else 0.

The other control factors in the model that have been shown to be related to going-concern report modifications, based on prior research (McKeown et al., 1991a; Chen and Church, 1992; Geiger and Raghunandan, 2001), are company size (LNSL), financial stress (PROB), default status (DFT), bankruptcy lag (BKTLAG), and audit reporting lag (REPLAG). Prior research suggests that there is a positive association between the likelihood of a going-concern modified audit opinion financial stress, default on debt obligations, reporting lag, and audit firm size, and a negative association between the likelihood of a going-concern modified audit opinion and company size and bankruptcy lag.

7 Using natural log of sales or total assets, or price-level adjusted total assets does not

substantively affect the results.

8 We useZmijewski’s (1984)bankruptcy model for his 40:800 bankrupt-to-non-bankrupt sample:

4.8033.599 (net income/total assets) + 5.406 (total debt/total assets)0.100 (current assets/ current liabilities).

9 Defining this variable as only payment default does not significantly change the reported results.

To examine the association between bankruptcies, prior audit opinions, and theReform Act, a list of public company bankruptcies for the years 1991–2001 was obtained from New Generation Research Inc., publishers of the yearly

Bankruptcy Almanac. Relevant financial statement data were obtained from

Compact Disclosure-SEC. Audit report data were obtained fromCompact Dis-closure-SEC and by examining 10-k filings. Consistent with prior research (Carcello et al., 1997; Mutchler et al., 1997; Carcello and Neal, 2003), we deleted companies in the banking, other financial, real estate, and utilities sec-tors because such companies have unique financial characteristics that are not modeled well with our measures of financial stress. For companies that had already filed for bankruptcy at the time the audit report was issued, we used their prior year’s financial statement data and audit report (McKeown et al., 1991a; Mutchler et al., 1997).

We were able to obtain audit reports and relevant data for 752 bankrupt companies during our sample period. We then eliminate 21 observations where the company had previously filed for bankruptcy during our sample period. Using the stress criteria discussed earlier, only 37 companies did not meet any of the stress criteria. Since the non-stressed sample has only 37 companies, we do not perform our logistic regression analysis on the sub-sample of non-stressed, bankrupt companies.10,11 After eliminating the non-stressed compa-nies, we arrived at our final sample of 694 stressed, bankrupt companies. The analyses presented in this paper are for these 261 pre-Reform Act and 433 post-Reform Actaudit opinions.

4. Results

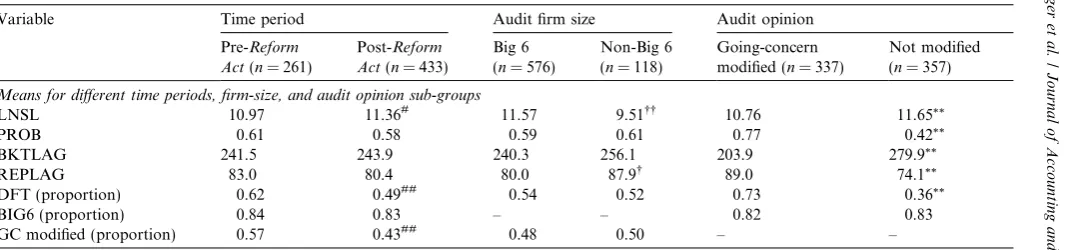

Table 1provides descriptive data about the sample of 694 stressed bankrupt companies and indicates that there are generally no significant differences for the sample of companies in the pre-Reform Actand post-Reform Actperiods on the control variables, except that the post-Reform Actcompanies are larger (p< 0.05) and less likely to be in default (p< 0.01). Additionally,Table 1 indi-cates that, in general, post-Reform Actcompanies are less likely to have received a going-concern modified report (p< 0.01). With respect to the Big 6 and non-Big 6 comparisons, the only differences on the control factors are that the non-Big 6 on average audited larger companies than the non-Big 6 audit firms (p< 0.01), and that the Big 6 have shorter average audit reporting lags (p< 0.05). There are significant differences atp< 0.01 for all of the control variables when comparing

10Stone and Rasp (1991)note that for logistic regression analysis, the number of observations

should be at least 15 times the number of variables included in the regression.

11Consistent with the arguments presented inHopwood et al. (1994), all of the 37 non-stressed

Table 1

Descriptive statistics (n= 694)

Variable Time period Audit firm size Audit opinion

Pre-Reform

Means for different time periods, firm-size, and audit opinion sub-groups

LNSL 10.97 11.36# 11.57 9.51

10.76 11.65**

PROB 0.61 0.58 0.59 0.61 0.77 0.42**

BKTLAG 241.5 243.9 240.3 256.1 203.9 279.9**

REPLAG 83.0 80.4 80.0 87.9 89.0 74.1**

DFT (proportion) 0.62 0.49## 0.54 0.52 0.73 0.36**

BIG6 (proportion) 0.84 0.83 – – 0.82 0.83

GC modified (proportion) 0.57 0.43## 0.48 0.50 – –

*, **Significantly different from modified opinion sample atp< 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. ,

Significantly different from the Big 6 sample atp< 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

#, ##

Significantly different from Pre-Reform Actsample atp< 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. LNSL = natural log of sales (in thousands of dollars) deflated to 1990 levels;

PROB = probability of bankruptcy, calculated fromZmijewski (1984)model; BKTLAG = number of days from audit report date to bankruptcy date; REPLAG = number of days from fiscal year end to audit report date; DFT = 1 if the company is in default, else 0;

the subsets of companies with and without a prior going-concern modified opin-ion (except for the BIG6 variable). Companies receiving a prior going-concern modified report are smaller, in greater financial stress, have shorter bankruptcy lags but longer reporting lags, and are more likely to be in default than compa-nies not receiving a going-concern modified report from their auditor prior to bankruptcy. These significant differences reinforce the need to control for these factors in our multivariate analysis of reporting behavior.

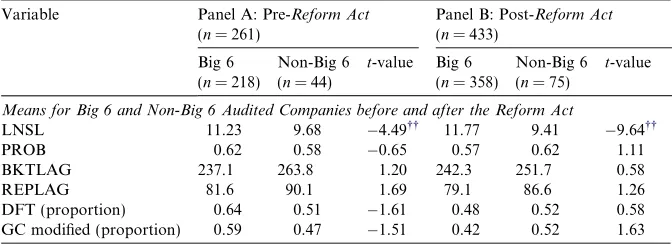

Table 2 further partitions the sample based on time period and audit firm size. Results of these pre- and post-Reform Act comparisons between Big 6 and non-Big 6 audited companies are consistent with the aggregate analyses presented inTable 1. The only significant difference with respect to the control variables between the companies audited by Big 6 audit firms and non-Big 6 audit firms is the size of the audited company (p< 0.01), in both time periods. The difference in reporting lags between the Big 6 and non-Big 6 firms noted in

Table 1 is not present in the separate analyses of pre- and post-Reform Act

periods. Additionally, univariate chi-square tests of association between audit firm size (BIG6) and audit opinion type (GC) are not significant at conven-tional levels (p> 0.05) for the combined sample or for the pre- and

post-Reform Act periods separately. However, a more comprehensive assessment of auditor reporting decisions and differential effects of audit firm size on audit opinion decisions following theReform Actrequires a multivariate analysis.

The correlations between all the variables used in our logistic regression mod-els (including the modmod-els discussed in Section 4.1) are presented in Table 3.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics

Variable Panel A: Pre-Reform Act

(n= 261)

Means for Big 6 and Non-Big 6 Audited Companies before and after the Reform Act

LNSL 11.23 9.68 4.49

11.77 9.41 9.64

PROB 0.62 0.58 0.65 0.57 0.62 1.11

BKTLAG 237.1 263.8 1.20 242.3 251.7 0.58

REPLAG 81.6 90.1 1.69 79.1 86.6 1.26

DFT (proportion) 0.64 0.51 1.61 0.48 0.52 0.58

GC modified (proportion) 0.59 0.47 1.51 0.42 0.52 1.63

Significant atp< 0.01.

LNSL = natural log of sales (in thousands of dollars) deflated to 1990 levels; PROB = probability of bankruptcy, calculated fromZmijewski (1984)model; BKTLAG = number of days from audit report date to bankruptcy date; REPLAG = number of days from fiscal year end to audit report date; DFT = 1 if the company is in default, else 0;

The correlations are generally small, with the highest correlation of 0.46 between getting a going-concern modified report (GC) and probability of failure (PROB). The highest correlations among the independent variables are found between the BIG6 and bankruptcy ratio (BKTRATIO) used in the sensitivity tests (0.39), and the BIG6 and LNSL size variable (0.36). All other correlations among the independent variables are below 0.25. To further assess the possible effects of the correlations among our independent variables on our logistic regression results, an examination of the variance inflation factors for all of the model variables used in this study reveals that the largest variance inflation factor value is only 2.8, which is well below the cut-off of 10.0 typically used to indicate a potential multicollinearity problem (Neter et al., 1985). These collec-tive results suggest that multicollinearity of the variables used in our models is unlikely to be a significant impediment in accurately estimating the model coefficients.

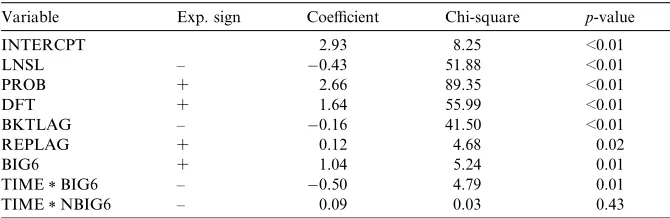

Results from the multivariate logistic regression are presented inTable 4.12 The overall model is significant (chi-square = 340.5, 8 d.f.,p< 0.0001;

pseudo-R2= 0.36) and the coefficients for all the control factors are in the expected directions and are significant at conventional levels (p< 0.05). The modelc

-sta-Table 3

Correlation matrix – stressed bankrupt company sample

Variable LNSL PROB DFT BKTLAG REPLAG BIG6 RISKY BKTRATIO

GC 0.21** 0.46** 0.38** 0.29** 0.19** 0.01 0.01 0.02

LNSL 0.05 0.12** 0.13** 0.04 0.36** 0.22** 0.23**

PROB 0.21** 0.16** 0.06 0.02 0.01 0.02

DFT 0.21** 0.22** 0.02 0.13** 0.06

BKTLAG 0.19** 0.05 0.01 0.14**

REPLAG 0.07* 0.03 0.06

BIG6 0.04 0.39**

RISKY 0.00

*, **Significant atp< 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

LNSL = natural log of sales (in thousands of dollars) deflated to 1990 levels; PROB = probability of bankruptcy, calculated fromZmijewski (1984)model; BKTLAG = number of days from audit report date to bankruptcy date; REPLAG = number of days from fiscal year end to audit report date; DFT = 1 if the company is in default, else 0;

BIG6 = 1 if audited by a Big 6 audit firm, else 0; RISKY = 1 if in a risky industry, else 0; and

BKTRATIO = ratio of bankruptcy filings to total audit clients for the reporting year.

12We also confirm that our overallReform Actresults are consistent with those ofGeiger and Raghunandan (2001)by using their model and including a TIME variable, while eliminating the BIG6, TIME * BIG6 and TIME * NBIG6 terms from our model. Results of this model are consistent with those of Geiger and Raghunandan (2001)in that we also find a negative and significant (p< 0.05) overall TIME coefficient.

tistic, indicating the percentage of correctly classified observations, is 0.87, pro-viding evidence that the model has a high degree of classification accuracy. Consistent with Lee and Mande (2003), the coefficient for the variable TIME * BIG6 is negative (0.50) and significant (p= 0.01), and the coefficient for the TIME * NBIG6 variable is positive (0.09) but not significant (p= 0.43), after controlling for other going-concern reporting related factors.

Separate tests of these two coefficients indicate that the TIME * BIG6 coef-ficient is significantly different from zero (p< 0.01), while the TIME * NBIG6 coefficient is not significantly different from zero (p> 0.25). Further, testing whether the two coefficients are equivalent indicates that they are significantly different (Wald chi-square = 6.66;p< 0.01), which supports HA. These results

suggest that the reduced litigation environment ushered in by theReform Act

did have a significant differential effect on reporting decisions for Big 6 audit firms compared to non-Big 6 audit firms. Our results indicate that Big 6 audit firms significantly reduced their propensity to issue a going-concern modified audit opinion to their financially stressed, subsequently bankrupt clients after the Reform Act, while the non-Big 6 audit firms exhibit no significant change after the Reform Act. Thus, as reflected in their reduced issuance of

Table 4

Logistic regression results – stressed bankrupt company sample

Model : GC¼aþb1LNSLþb2PROBþb3DFTþb4BKTLAGþb5REPLAGþb6BIG6

þb7TIMEBIG6þb8TIMENBIG6

Variable Exp. sign Coefficient Chi-square p-value

INTERCPT 2.93 8.25 <0.01

LNSL – 0.43 51.88 <0.01

PROB + 2.66 89.35 <0.01

DFT + 1.64 55.99 <0.01

BKTLAG – 0.16 41.50 <0.01

REPLAG + 0.12 4.68 0.02

BIG6 + 1.04 5.24 0.01

TIME * BIG6 – 0.50 4.79 0.01

TIME * NBIG6 – 0.09 0.03 0.43

Model chi-square = 340.5; 8 d.f.;p< 0.0001;c-statistic = 0.87; pseudo-R2= 0.36.

Note: p-values are one-tail, except for the intercept.

LNSL = natural log of sales (in thousands of dollars) deflated to 1990 levels; PROB = probability of bankruptcy, calculated fromZmijewski (1984)model; BKTLAG = number of days from audit report date to bankruptcy date; REPLAG = number of days from fiscal year end to audit report date; DFT = 1 if the company is in default, else 0,

GC = 1 if audit report prior to bankruptcy was modified for going concern, else 0; BIG6 = 1 if audited by a Big 6 audit firm, else 0;

going-concern modified audit reports, the Big 6 firms were significantly less conservative following theReform Actcompared to their decisions in the per-iod prior to theReform Act. These findings are consistent with those ofLee and Mande (2003)who indirectly examined the effect of theReform Acton audit firm decision-making. Our results also suggest that the Big 6 firms were more affected by the passage of theReform Act as reflected in their audit reporting decisions on the financially stressed, bankrupt companies in our sample.13

4.1. Sensitivity and additional analyses

4.1.1. Additional Big 6/non-Big 6 analyses

We re-perform our analyses separately for the Big 6 and non-Big 6 audit firms. The results of the models including a TIME variable (and eliminating the BIG6, TIME * BIG6 and TIME * NBIG6 terms) and using only the Big 6 firms or the non-Big 6 firms are presented in Panel A ofTable 5. The results indicate that the Big 6 firms were significantly less likely to issue a going-concern mod-ified opinion after the Reform Act compared to before the Reform Act (p= 0.02). However, the model results for the non-Big 6 firms alone indicates no significant change in opinion modification propensities from the period before to the period after theReform Act(p= 0.47). This provides additional evidence to our significant TIME * BIG6 interaction term and our non-significant TIME * NBIG6 interaction term in the main analysis, suggesting theReform Acthad a significant effect on the Big 6 but not the non-Big 6 reporting decisions.

Panel B ofTable 5presents the results of separately assessing the time peri-ods before and after the Reform Actfor a Big 6 reporting effect by including only a BIG6 indicator variable for the two separate time periods. The results indicate that the Big 6 firms were significantly more likely to issue a going-con-cern modified opinion than the non-Big 6 firms, and therefore were relatively more conservative in their report decision-making, in the period before the

Reform Act (p= 0.01). This significant Big 6 reporting difference, while in the same direction, is not significant in the period following the Reform Act

(p= 0.10). These additional tests further indicate that the effect of theReform Acton going-concern reporting decision-making was much more pronounced for the Big 6 audit firms than for the non-Big 6 firms, causing the Big 6 firms after theReform Actto report more similarly to the non-Big 6 firms.

4.1.2. Client size

Prior studies examining the impact of audit firm size on audit fees have examined the small client market (Francis and Simon, 1987; Gist, 1995),

13Including the non-stressed bankrupt companies in our analyses, or including the companies that

filed for bankruptcy more than once during our examination period does not substantively alter the results.

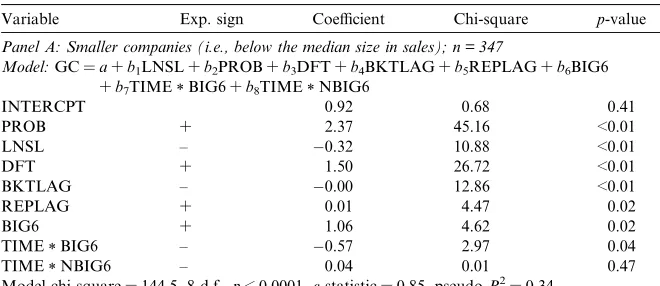

arguing that non-Big 6 audit firms rarely audit very large companies. Accord-ingly, we eliminated the 347 companies in the upper half of our firm size mea-sure (LNSL), thereby restricting the analysis to companies that were smaller and more likely to have a choice of Big 6 or non-Big 6 audit firms. This sample restriction removes proportionately more of the Big 6 clients and leaves 244 companies audited by Big 6 audit firms (out of the original 576) and 103

Table 5

Logistic regression results – additional tests – Big 6 partitions

Variable Exp. sign BIG 6 (n= 576) Non-Big 6 (n= 118)

Coefficient Chi-square p-value Coefficient Chi-square p-value

Panel A: Model:GC =a+b1LNSL +b2PROB +b3DFT +b4BKTLAG +b5REPLAG +b6TIME

INTERCPT 3.99 20.27 <0.01 0.11 0.00 0.95

LNSL – 0.47 50.79 <0.01 0.17 1.73 0.09

PROB + 2.485 64.70 <0.01 3.45 25.00 <0.01

DFT + 1.67 48.18 <0.01 1.48 8.28 <0.01

BKTLAG – 0.01 33.08 <0.01 0.00 5.52 <0.01

REPLAG + 0.01 4.47 0.02 0.00 0.01 0.46

TIME – 0.47 4.26 0.02 0.04 0.01 0.47

Model chi-square = 282.7,

p< 0.0001,c-statistic = 0.88, pseudo-R2= 0.39

Model chi-square = 58.7,

p< 0.0001,c-statistic = 0.87, pseudo-R2= 0.39

Before theReform Act(n= 261) After theReform Act(n= 433) Coefficient Chi-square p-value Coefficient Chi-square p-value

Panel B: Model:GC =a+b1LNSL +b2PROB +b3DFT +b4BKTLAG +b5REPLAG +b6BIG6

INTERCPT 1.49 1.38 0.24 3.50 13.48 <0.02

LNSL – –0.49 22.30 <0.01 0.44 31.66 <0.01

PROB + 3.66 50.29 <0.01 2.13 39.04 <0.01

DFT + 1.84 23.08 <0.01 1.52 32.31 <0.01

BKTLAG – 0.00 4.70 0.02 0.01 36.15 <0.01

REPLAG + 0.01 1.64 0.10 0.00 2.10 0.07

BIG6 + 1.14 5.23 0.01 0.46 1.64 0.10

Model chi-square = 135.2,

p< 0.0001,c-statistic = 0.89, pseudo-R2= 0.41

Model chi-square = 199.5,

p< 0.0001,c-statistic = 0.87, pseudo-R2= 0.37

Note: p-values are one-tail, except for the intercept.

LNSL = natural log of sales (in thousands of dollars) deflated to 1990 levels; PROB = probability of bankruptcy, calculated fromZmijewski (1984)model; BKTLAG = number of days from audit report date to bankruptcy date; REPLAG = number of days from fiscal year end to audit report date; DFT = 1 if the company is in default, else 0;

GC = 1 if audit report prior to bankruptcy was modified for going concern, else 0; TIME = 1 if post-Reform Act, else 0; and

companies audited by non-Big 6 firms (out of the original 118).14 Results of this restricted-sample analysis are reported in Panel A ofTable 6and are essen-tially the same as those reported in Table 4for the full sample. The TIME * BIG6 variable was negative and significant (p= 0.04), and the TIME * NBIG6 variable was positive but not significant (p= 0.47). Thus, our results do not appear to be driven by audit firm reporting decisions on the larger companies in our sample who may not reasonably be in the market for a non-Big 6 audit firm.

4.1.3. Changes in client risk portfolios

To examine if our findings of a differentialReform Act reporting effect are driven by significant structural changes in the client risk portfolios of the Big 6 and non-Big 6 before and after the enactment of the Reform Act, we added two additional control variables to the logistic regression. First, we add a risky industry indicator variable (RISKY) to control for changes in relative overall client risk profiles of the Big 6 and non-Big 6 firms. Thus, following

Kasznik and Lev (1995), we code the RISKY indicator variable a 1 if the cli-ent company operated in a risky industry for auditor litigation as idcli-entified by SIC codes 2833-2836, 3570-3577, 3600-3674, 7372-7379 and 8731-8734, and a 0 otherwise. Second, we include a variable for the bankruptcy-to-clients ratio (BKTRATIO) into the logistic regression. Inclusion of the ratio of clients fil-ing for bankruptcy to every 1000 audit clients in each year for the Big 6 as a group and non-Big 6 firms as a group provides an additional control for the possible effect the actual proportion of bankrupt clients audited by these two groups on their respective going-concern modification decisions. Inclusion of this variable also provides some additional control over the relative levels of client risk (as reflected in actual bankruptcy filings) portfolio changes of the two sized audit firms in our study. We would expect that increasing the num-ber of risky industry clients and an increase in the ratio of bankruptcies to audit clients would both be associated with increased going-concern modified reports.

Results of the expanded logistic regression model including these two addi-tional control variables are presented in Panel B ofTable 6. As indicated in the table, this expanded model produces similar results for the TIME * BIG6 and TIME * NBIG6 terms as in the original model presented inTable 4. In fact, the results are stronger with respect to a Big 6 reporting effect after theReform Act

(p< 0.01 in the expanded model and 0.01 in the original model), yet the expanded regression continues to fail to find a significantReform Actreporting

14Alternatively, eliminating the upper quartile of companies in our sample leaves 404 companies

audited by Big 6 audit firms (out of the original 576) and 116 companies audited by non-Big 6 firms (out of the original 118) and produces similar results.

effect for the non-Big 6 (p= 0.37). The additional control variable for risky industry (RISKY) is not significant at conventional levels (p= 0.33); however, the bankruptcy ratio (BKTRATIO) is significantly positively associated with

Table 6

Logistic regression results – additional tests – client characteristics

Variable Exp. sign Coefficient Chi-square p-value

Panel A: Smaller companies (i.e., below the median size in sales); n = 347

Model:GC =a+b1LNSL +b2PROB +b3DFT +b4BKTLAG +b5REPLAG +b6BIG6 +b7TIME * BIG6 +b8TIME * NBIG6

INTERCPT 0.92 0.68 0.41

PROB + 2.37 45.16 <0.01

LNSL – 0.32 10.88 <0.01

DFT + 1.50 26.72 <0.01

BKTLAG – 0.00 12.86 <0.01

REPLAG + 0.01 4.47 0.02

BIG6 + 1.06 4.62 0.02

TIME * BIG6 – 0.57 2.97 0.04

TIME * NBIG6 – 0.04 0.01 0.47

Model chi-square = 144.5, 8 d.f.,p< 0.0001,c-statistic = 0.85, pseudo-R2= 0.34

Panel B: Additional control variables for client portfolio characteristics

Model:GC =a+b1LNSL +b2PROB +b3DFT +b4BKTLAG +b5REPLAG +b6RISKY +b7BKTRATIO +b8BIG6 +b9TIME * BIG6 +b10TIME * NBIG6

INTERCPT 2.28 7.87 <0.01

PROB + 2.66 91.52 <0.01

LNSL – 0.43 50.45 <0.01

DFT + 1.65 57.60 <0.01

BKTLAG – 0.00 32.14 <0.01

REPLAG + 0.01 4.21 0.02

RISKY + 0.13 0.19 0.33

BKTRATIO + 0.06 2.84 0.05

BIG6 + 0.81 2.91 0.04

TIME * BIG6 – 0.76 7.35 <0.01

TIME * NBIG6 – 0.16 0.10 0.37

Model chi-square = 366.8, 10 d.f.,p< 0.0001,c-statistic = 0.87, pseudo-R2= 0.38

Note: p-values are one-tail, except for the intercept.

GC = 1 if audit report prior to bankruptcy was modified for going concern, else 0; LNSL = natural log of sales (in thousands of dollars) deflated to 1990 levels; PROB = probability of bankruptcy, calculated fromZmijewski (1984)model; BKTLAG = number of days from audit report date to bankruptcy date; REPLAG = number of days from fiscal year end to audit report date; DFT = 1 if the company is in default, else 0;

RISKY = 1 if in a risky industry, else 0;

BKTRATIO = ratio of bankruptcy filings to 1000 audit clients for the reporting year; BIG6 = 1 if audited by a Big 6 audit firm, else 0;

going-concern modified report decisions (p= 0.05), indicating that the propor-tion of actual client bankruptcy filings is positively associated with going-con-cern reporting decisions. Additional analyses of the BKTRATIO (not tabulated) reveal that this measure was generally increasing for both sized audit firms across our entire examination period, and that it was significantly higher for the Big 6 firms than the non-Big 6 firms both before and after the

Reform Act, as well as significantly increased for both sized firms following the Reform Act (p< 0.001). Accordingly, the BKTRATIO appears to have been consistently higher for the Big 6 firms, and to have changed fairly uni-formly after the Reform Act for both sized firms. Thus, at least as captured in our additional measures (i.e., RISKY and BKTRATIO), our primary results regarding opinion decisions do not appear to be significantly driven by shifts in risk profiles of the client portfolios of the Big 6 and non-Big 6 before and after theReform Act.

4.1.4. Cut-off dates

The results ofCarcello et al. (1997)underscore the importance of transition periods in examining issues related to audit opinions. With respect to the

Reform Act, the process to arrive at the final legislation progressed throughout 1995, and we can not fully ascertain or control for whether the accounting firms anticipated the eventual passage of the Reform Act and modified their reporting decisions prior to final passage or the effective date of theAct. There-fore, consistent with Lee and Mande (2003), as sensitivity tests we eliminate audit reports dated in 1995 and in 1996. Additionally, it could be argued that audit reporting behavior would not have changed immediately after the effec-tive date of the new law or even in the subsequent year under the new law, and that audit reporting behavior would have changed only after some time had elapsed. Accordingly, we perform additional sensitivity tests by separately deleting audit reports relating to fiscal years beginning in 1996 and in 1997. Finally, it could be argued that the reporting behavior of audit firms may have changed as soon as the Reform Act was enacted. Thus, we re-perform our analyses using December 22, 1995 as the cut-off date for the pre-Reform Act

period.

Results of these restricted samples and modified cut-off dates (not tabulated) are essentially the same as those presented. Using the logistic regression model presented in Table 4 with these modified samples and time periods, the TIME * BIG6 variable remained negative and significant (p< 0.05), yet the TIME * NBIG6 variable continued to be non-significant (p> 0.25) in all of the logistic regressions. Specifically, thep-value for the TIME * BIG6 variable ranged from 0.03 to 0.05 and thep-value for the TIME * NBIG6 variable ran-ged from 0.29 to 0.46 in such analyses. Further, tests for equivalence of the TIME * BIG6 and TIME * NBIG6 coefficients continue to indicate that they

are significantly different (p< 0.05) in each of the modified analyses. Thus, our results do not appear to be sensitive to our selection of cut-off dates or to reporting decisions in the periods immediately surrounding the passage of theReform Act.

5. Summary and conclusions

The enactment of thePrivate Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995had a marked impact on the legal environment of public accounting firms in the US. This shift in the litigation environment has been argued to have been manifest in changed auditor decisions regarding their publicly traded audit clients. In this study we examine whether the changed litigation environment following the Pri-vate Securities Litigation Reform Acthad a differential effect on the reporting decisions of both the Big 6 and non-Big 6 audit firms. Our analysis of audit firm going-concern modification decisions on companies that filed for bankruptcy in the period from 1991 to 2001 presents evidence that the changed litigation envi-ronment ushered in by theReform Actsignificantly affected the reporting deci-sions of the Big 6 audit firms but not the non-Big 6 audit firms. Specifically, we find that Big 6 firms became less conservative following the adoption of the

Reform Actas reflected in their lower propensity to issue going-concern modi-fied audit opinions, while the non-Big 6 firms exhibited no such change in reporting propensities. Our additional tests indicate that the Big 6 firms report more similarly to the non-Big 6 firms after the Reform Act than prior to its adoption. Further, our results are robust to various partitions of our sample companies, additional controls for reducing the effect of possible changes in overall client risk portfolios over our examination period, and the examination of different transition periods for this important legislation.

While our study presents consistent evidence with respect to changes in audit reporting decisions of the Big 6 firms after theReform Act, we have exam-ined only reporting decisions immediately preceding client bankruptcies (i.e., type II reporting errors). It also appears worthwhile to examine if the proba-bility of going-concern modified opinions for subsequently viable companies (i.e., type I reporting errors) have differentially changed between Big 6 and non-Big 6 firms in the post-Reform Act period. Receiving a going-concern modified audit opinion, particularly if the company remains viable, also imposes costs on clients, auditors, and financial statement users (Geiger et al., 1998; Carcello and Neal, 2003). The examination of these reporting deci-sions would also contribute to our knowledge of the effect of theReform Acton audit firm reporting behavior under different liability regimes.

Another fruitful avenue for research would be to examine the impact of the

those related to client acceptance and retention decisions (e.g.,Gramling et al., 1998). In our study we find a significant effect in our sensitivity tests between the ratio of bankruptcies-to-clients (BKTRATIO) and a firm’s going concern reporting decisions. Additional analyses of this ratio reveal that it was signifi-cantly higher for the Big 6 firms than the non-Big 6 firms both before and after theReform Act, as well as significantly increased for both sized firms following theReform Act(p< 0.001). An interesting avenue for future research would be to further explore these differences and possible changes in client portfolios (measured in different ways) in an effort to assess whether the Reform Act

encouraged firms of different sizes to alter their portfolio of clients in response to the changed litigation environment. While we find similar changes across time and firm size with respect to bankruptcy ratios, a more directed study appears warranted based on our tentative findings.

Our results support the argument that while the Reform Act may have provided important litigation relief to the public accounting profession in general, the Big 6 audit firms appear to have been the greatest beneficiaries and were affected more than non-Big 6 firms (Coffee, 2002; Lee and Mande, 2003). Our findings bolster the argument that this substantial change in tort policy in the US that reduced the litigation exposure of auditors of public companies significantly affected only the largest accounting firms’ reporting decisions. An important public policy issue is whether national legislative changes or tort reforms should be implemented that have differential effects on different sized audit firms, or whether these effects are simply the expected result of reforms necessary to balance appropriate legal recourse for damaged parties and yet ensure adequate auditing of all publicly traded companies.

References

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), 1988. The Auditor’s Consideration of an Entity’s Ability to Continue as a Going Concern. Statement on Auditing Standards no. 59. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, New York.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), 1992. Statement by the Board of Directors of the AICPA. In Journal of Accountancy 182 (5), 18.

Berton, L., 1995. Big accounting firms weed out risky clients. The Wall Street Journal, B1. Boyle, E.J., Knopf, F.N., 1996. The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. CPA Journal

66 (4), 44–47.

Breeden, R., 2002. Oversight hearing on accounting and investor protection issues raised by Enron and other public companies. US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, Washington, DC.

Bryan-Low, C., 2002. Auditors fail to foresee bankruptcies: In study, many companies were cleared within a year before chapter 11 filings. The Wall Street Journal, C9.

Carcello, J., Neal, T.L., 2003. Audit committee characteristics and auditor dismissals following ‘‘new’’ going-concern reports. The Accounting Review 78 (1), 95–117.

Carcello, J., Palmrose, Z., 1994. Auditor litigation and modified reporting on bankrupt companies. Journal of Accounting Research 32 (Supplement), 1–30.

Carcello, J., Hermanson, D., Huss, F., 1997. The effect of SAS No. 59: How treatment of the transition period influences results. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 16 (1), 114– 123.

Chan, D., Pae, S., 1998. An analysis of the economic consequences of the proportionate liability rule. Contemporary Accounting Research 15 (2), 457–480.

Chen, K.C.W., Church, B.K., 1992. Default on debt obligations and the issuance of going-concern opinions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 11 (2), 30–49.

Chenok, P., 1994. Worth repeating. Journal of Accountancy 184 (6), 47–50.

Cloyd, C.B., Frederickson, J.R., Hill, J.W., 1998. Independent auditor litigation: Recent events and related research. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 17, 121–142.

Coffee, J.C., 2002. Guarding the gatekeepers. The New York Times, B3.

Cook, J.M., Freedman, E.M., Groves, R.J., Madonna, J.C., O’Malley, S.F., Weinbach, L.A., 1992. The liability crisis in the United States: Impact on the accounting profession. Journal of Accountancy 182 (5), 19–23.

Dye, R., 1993. Auditing standards, legal liability, and auditor wealth. Journal of Political Economy 101, 887–908.

Francis, J.R., Krishnan, J., 1999. Accounting accruals and auditor reporting conservatism. Contemporary Accounting Research 16 (1), 135–165.

Francis, J.R., Simon, D.T., 1987. A test of audit pricing in the small client segment of the US audit market. The Accounting Review 72 (1), 145–157.

Geiger, M.A., Raghunandan, K., 2001. Bankruptcies, audit reports, and the reform act. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 20 (1), 187–195.

Geiger, M.A., Raghunandan, K., Rama, D.V., 1998. Costs associated with going-concern modified audit opinions: An analysis of auditor changes, subsequent opinions, and client failures. Advances in Accounting 16, 117–139.

Gist, W.E., 1995. A test of audit pricing in the small-client segment: A comment. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance 10 (2), 223–233.

Gottlieb, E., Doroshow, J., 2002. Not in my back yard II: The high-tech hypocrites of ‘‘tort reform.’’ Center for Justice and Democracy, White paper (April).

Gramling, A.A., Schatzberg, J.W., Bailey Jr., A.D., Zhang, H., 1998. The impact of legal liability regimes and differential client risk on client acceptance, audit pricing, and audit effort decisions. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance 13 (2), 437–460.

Hopwood, W., McKeown, J., Mutchler, J., 1989. A test of the incremental explanatory power of opinions qualified for consistency and uncertainty. The Accounting Review 64 (1), 28– 48.

Hopwood, W., McKeown, J., Mutchler, J., 1994. A reexamination of auditor versus model accuracy within the context of the going-concern opinion decision. Contemporary Accounting Research 11 (1), 409–431.

Johnson, R., Stokes, D., Watts, D., 1995. Auditor preferences for liability limitation. Accounting and Finance 35 (1), 135–154.

Kahn, L., Metcalfe, L., 1996. Securities law: Accountants no longer at risk of being sued for aiding and abetting securities law violations, have recently been found directly liable for their client’s fraud. The National Law Journal 20, B6.

Kasznik, R., Lev, B., 1995. To warn or not to warn: Management disclosures in the face of an earnings surprise. The Accounting Review 69 (1), 113–134.

King, R.R., Schwartz, R., 1997. The Private Securities Reform Act of 1995: A discussion of three provisions. Accounting Horizons 11 (1), 92–106.

Lee, H.Y., Mande, V., 2003. The effect of the Private Securities Reform Act of 1995 on accounting discretion of client managers of Big 6 and non-Big 6 auditors. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 22 (1), 93–108.

McKeown, J.C., Mutchler, J.F., Hopwood, W., 1991a. Towards an explanation of auditor failure to modify the audit opinion of bankrupt companies. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 10 (Supplement), 1–13.

McKeown, J.C., Mutchler, J.F., Hopwood, W., 1991b. Reply. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 10 (Supplement), 21–24.

Mednick, R., Peck, J.J., 1994. Proportionality: A much-needed solution to the accountants’ legal liability crisis. Valparaiso University Law Review (23), 867–918.

Menon, K., Williams, D., 1994. The insurance hypothesis and market prices. The Accounting Review 69 (2), 327–342.

Mutchler, J.F., Hopwood, W., McKeown, J.C., 1997. The influence of contrary information and mitigating factors on audit opinion decisions on bankrupt companies. Journal of Accounting Research 36 (2), 295–310.

Nelson, S., 2002. Push is on for audit reform, before sting of Andersen verdict fades. The Boston Globe, B1.

Neter, J., Wasserman, W., Kunter, M.H., 1985. Applied Linear Statistical Models, second ed. Richard D. Irwin, Homewood, IL.

Pratt, J., Stice, J.D., 1994. The effects of client characteristics on auditor litigation risk judgments, required audit evidence, and recommended audit fees. The Accounting Review 69 (4), 639– 656.

Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, 1995. Government Printing Office (GPO), Private Securities Litigation Reform Act. Public Law No. 104-67. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Public Oversight Board (POB), 1993. Annual report 1992–1993. Public Oversight Board, Stamford, CT.

Public Oversight Board (POB), 1994. Annual report 1993–1994. Public Oversight Board, Stamford, CT.

Raghunandan, K., Rama, D.V., 1995. Audit opinions for companies in financial distress: Before and after SAS No. 59. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 14 (1), 50–63. Raghunandan, K., Rama, D.V., 1999. Auditor resignations and the market for audit services.

Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 18 (1), 124–134.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), 2000. Revision of the commission’s auditor independence requirements. Release Nos. 33-7919; 34-43602. Securities and Exchange Com-mission, Washington, DC.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), 2002. Strengthening the Commission’s Requirements Regarding Auditor Independence, Securities and Exchange Commission, Release No. 33-8154 SEC: Washington, DC.

Shu, S., 2000. Auditor resignations: Clientele effects and legal liability. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33, 173–205.

Stice, J.D., 1991. Using financial and market information to identify pre-engagement factors associated with lawsuits against auditors. The Accounting Review 66 (3), 516–533.

Stone, M., Rasp, J., 1991. Tradeoffs in the choice between Logit and OLS for accounting choice studies. The Accounting Review 66 (1), 170–187.

Tie, R., 2003. The profession’s roots. Journal of Accountancy 193 (5), 57–59.

US Senate., 2002. Hearings before the subcommittee on telecommunications and finance of the committee on energy and commerce.

Weil, J., 2001. Going concerns: Did accountants fail to flag problems at dot-com casualties? The Wall Street Journal, C1.

Williams, P., 2003. Association for integrity in accounting enters the discussion of accounting reforms. The CPA Journal 73 (4), 14–15.