A Balancing Act: Emotional Challenges in the HR Role

Elaine O’Brien and Carol Linehan

University College CorkABSTRACT Despite much academic work and the development of multiple typologies, we are still some way from understanding the HR role. There is a dearth of empirical evidence on HR professionals’ work and recent models have been criticized for not adequately reflecting the challenges of trying to balance competing stakeholder interests. We approach this lacuna by focusing on an issue that has not been fully considered in relation to HR work – emotion. Drawing on the findings of a broader study into emotional labour, we highlight the emotive challenges inherent in the day-to-day practice of HR. We explore the disjunctions between ‘felt’ emotions and those actually displayed to meet differing stakeholders’ expectations. We show how achieving an appropriate emotion display is a challenging pursuit given these competing expectations. Our contribution is to elucidate emotional labour in the

under-researched ‘backstage’ professional context, and through our emotion focus to extend our understanding of the complexity of the HR role beyond current prescriptive models.

Keywords: display rules, emotion, emotional labour, HR role, role expectations

INTRODUCTION

The role that human resource (HR) professionals should and do play in the effective management of the employment relationship remains controversial territory. This is despite much scholarly work, and the development of multiple HR models and typolo-gies (e.g., Legge, 1978; Storey, 1992; Tyson and Fell, 1986; Ulrich, 1997; Ulrich and Brockbank, 2005; Watson, 1977). Contemporary models propose that the profession occupies a strategic business partner role, but a closer reading of the critical HR management (HRM) literature demonstrates that debate regarding the empirical validity and usefulness of such models continues (Caldwell, 2003; Caldwell and Storey, 2007; Sisson and Storey, 2000). Criticism centres on a lack of acknowledgment of the inherent duality in HR work arising from competing role demands and trade-offs between employee needs and organizational objectives. In turn, it is argued that the paradoxes facing the HR practitioner in their everyday work are downplayed (e.g., Caldwell, 2003;

Address for reprints: Elaine O’Brien, School of Management & Marketing, College of Business & Law, University College Cork, College Road, Cork, Ireland (elaine.obrien@ucc.ie).

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies

Francis and Keegan, 2006; Hope-Hailey et al., 2005; Legge, 2005; Truss et al., 2002) and the emotional challenges these create ignored (Hiillos, 2004; Rynes, 2004). Further-more, our understanding of how the HR role is actually played by practitioners is limited (Truss et al., 2002), due to the fact that there are few detailed empirical studies that focus on how HR professionals do their jobs (Farndale and Brewster, 2005; Pritchard, 2010; Watson, 2004).

We argue that focusing on the emotional challenges involved in HR work is a useful way to deepen our understanding of the role, and to move beyond prescriptive accounts. Studies of emotion have an increasing profile in organizational research (e.g., Ashkanasy, 2002; Barsade et al., 2003; Bolton, 2000). Much of this renewed interest stems from Arlie Hochschild’s (1983) seminal book The Managed Heart in which she proposed the notion of ‘emotional labour’. Hochschild used this term to describe how employees manage feelings and emotional expression at work to display organizationally desired emotions, which are encapsulated in ‘display rules’ (Ekman, 1972). Her empirical work highlighted how emotion management at work can make a vital contribution to an organization’s success. In turn, the idea that emotion can be key to achieving a competitive advantage captivated many organizations, and changes in the types of emotion management performances demanded of employees is well documented (e.g., Ashkanasy and Daus, 2002; Brotheridge and Grandey, 2002; Van Maanen and Kunda, 1989).

Emotion has however, with a few exceptions (see Hiillos, 2004; Rynes, 2004), yet to be explored in relation to the work of HR professionals. This is despite the emotionally challenging situations that inevitably arise out of, for example, performance manage-ment or restructuring and redundancy programmes and from the everyday challenges of dealing with the (often competing) needs of organizational stakeholders. The current paper explores this lacuna in our understanding of the HR role. It draws on the findings of a broader empirical study which investigated emotional labour (EL) in the HR context and provides an insight into HR professionals’ EL, illuminating participants’ understand-ing of their role and of the organizational and occupational expectations placed upon them by various stakeholders.

Using the lens of EL has the potential to make unique contributions to debate about the HR role. First, it could be argued that by investigating the EL of HR professionals we tap into the critical events and experiences (both positive and negative) beyond the prescriptive rhetoric about what HR ‘ought’ to be about. By asking participants to recount events requiring EL, our approach sheds light on their triumphs, challenges, and conflicts. Second, the blending of ‘emotion’ and ‘role’ in our investigation seems par-ticularly congruent as we draw on a conception of ‘role’ that assumes it is fluid, enacted, and constructed from interactions with stakeholders who may accept/reject/resist par-ticular positionings (Davies and Harre, 1999; Harre and van Langenhove, 1999; Truss et al., 2002). We uncover contested and emotive elements of HR work and thus a more analytic account of the role is offered than extant conceptions.

discussion of how the insights provided here contribute to our understanding of the HR role and of EL in backstage roles.

Duality and Paradox in the HR Role

The HR role is complex and paradoxical in nature. HR practitioners face divergent expectations and must negotiate the needs and values of multiple stakeholders. From an organizational point of view, the primary role of an HR professional is to contribute to strategic business objectives by ensuring that adequate numbers of employees exist, with the right skills, in the right positions, to achieve business goals (e.g., profitability, expan-sion into new markets). As a business partner and service provider, the HR role holder must provide managers with information about people-related issues, ensure employee compliance with company policy, provide employees with timely pay and benefit infor-mation, provide training, and undertake many other tasks associated with achieving bottom-line results (Becker and Huselid, 1998). For employees however, traditional conceptions of HR as primarily a ‘welfare’ role tend to persist and drive expectations of role behaviour (Bolton and Houlihan, 2007; Sisson and Storey, 2000). Employees tend to see the HR professional as someone who will care for their needs and champion their cause.

The HR role is also framed by the broader academic and occupational context. The rise of HRM and the changing nature of HR work have exposed practitioners to new demands and professional challenges, and many different typologies have been offered to capture such changes. Most contemporary HR models incorporate both people and process aspects of the role as well as operational and strategic activities. For instance, according to Ulrich and Brockbank, the HR professional must be an ‘administrative expert’ with an operational focus on improving organizational efficiency but they must also be a ‘strategic partner’ and have a future focus of aligning people management with business strategies. Additionally, they must be an ‘employee advocate’ and ‘human resource developer’ responsible for listening to and responding to employees but also ensuring that the employer–employee relationship is one of reciprocal value (Ulrich and Brockbank, 2005). This ‘business partner’ framework has been trumpeted as the aspirational ideal for the HR profession (Caldwell, 2003).

HR professionals, it seems, are expected to simultaneously deliver on both social and economic criteria (Bolton and Houlihan, 2007). They face the paradox of trying to meet the dual goals of protecting employee interests while becoming a business partner; trying to negotiate the ‘caring’ and ‘control’ aspects of the job while keeping all parties ‘on-side’; and trying to maintain an image of competence and credibility in the eyes of manage-ment by implemanage-menting strategies and practices that respond to economic circumstances whilst maintaining the trust of the workforce.

different conceptualizations of professionalism (see Muzio et al., 2013 for an overview), there is a literature that examines how professionals attempt to construct coherent professional identities (e.g., Dirsmith et al., 1997; Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2003). These however do not tend to focus onemotional demands. There are a few exceptions (e.g., Cascon-Pereira and Hallier, 2012; Harris, 2002; Kosmala and Herrbach, 2006). Kosmala and Herrbach (2006), for instance, explored how varying aspects of profession-alism can engender conflicting emotions for auditors. In brief, they argue that the clash of values of professionalism (built on knowledge base and expertise and involving an ethical dimension to auditing) and commercialism (based on being business orientated to maximize revenue) are irreconcilable. This creates stress and results in auditors adopting a distancing attitude at work.

In common with these professionals, HR practitioners must learn how to inhabit and enact their role and adhere to their own and other stakeholders’ expectations. The complexities and emotional challenges involved in this role enactment are not adequately reflected in contemporary HR models such as those proposed by Ulrich and colleagues. The dual goals of protecting employee interests while increasing efficiency are acknowledged but unitarist assumptions of a happy coincidence between employer and employee needs and interests are taken for granted and the conflicts that face the HR practitioner are downplayed (Caldwell, 2003; Francis and Keegan, 2006; Hope-Hailey et al., 2005; Legge, 2005; Truss et al., 2002). In turn the ambiguity in HR work (origi-nally highlighted in the writings of Legge, 1978 and Watson, 1977, 1986) has been neglected (e.g., Francis and Keegan, 2006; Keenoy, 1997, 1999) and the challenges facing practitioners in trying to achieve a balance between stakeholders’ interests has not been given due consideration. As a consequence little is known about the internal role conflicts and professional and emotional challenges that arise when competing needs collide (Hiillos, 2004; Rynes, 2004).

Emotional Labour

response, the employee regulates their emotion and emotional expression to meet the requirements of their job and achieve organizational goals.

Emotional labour is different to considering emotion as a reaction to work because it refers tointentionalefforts to convince others that one feels a particular emotion so as to influence how they perceive and react to a situation. It can also be distinguished from emotional intelligence (EI), described as ‘the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and action’ (Salovey and Mayer, 1990, p. 189). As Fabian (1999) suggests, EI is having the ability and EL is acting on that ability. EL also recognizes that emotional functioning is situation dependent and influenced by display rules and norms.

Numerous job roles have been shown to require EL, including service personnel such as waiters/waitresses, call centre agents, and other customer service representatives (e.g., Grandey et al., 2005; Korczynski, 2003; Shani et al., 2014; Van Maanen, 1991); healthcare workers (e.g., nurses; Smith, 1992); and police officers (e.g., Rafaeli and Sutton, 1991). The effective management of emotional expression has been linked to improvements in sales, quality of team decisions and negotiations (e.g., Grandey and Brauburger, 2002; Pugh, 2001) and is increasingly seen as essential in achieving bottom line results for the organization. Despite the burgeoning studies and advances in conceptualization (e.g., Ashforth and Humphrey, 1993; Grandey, 2000; Morris and Feldman, 1996; Zapf, 2002) our understanding of the EL phenomenon is largely derived from a ‘front of house’ customer-facing service context. This is because EL has primarily been conceptualized as the duty of service personnel interacting with customers or the general public and research has been biased towards this domain (e.g., Ashforth and Humphrey, 1993; Ashkanasy and Daus, 2002; Hochschild, 1983; Morris and Feldman, 1996). It is only relatively recently that researchers have gone beyond the traditional focus to explore EL in ‘backstage’ settings (see Brotheridge and Grandey, 2002; Ogbonna and Harris, 2004; Roach Anleu and Mack, 2005). Indications are that EL is an important issue in communications between colleagues and with supervisors (Kramer and Hess, 2002; Tschan et al., 2005), amongst leaders (Humphrey et al., 2008), and for professional level employees including barristers (Harris, 2002), magistrates (Roach Anleu and Mack, 2005), and lecturers (Ogbonna and Harris, 2004), and is in fact critical to effective job performance. It has also been suggested that the requirement to control emotional display on the job will intensify for most job roles (Zapf, 2002) and that to arrive at a more complete understanding of this increasingly important organizational issue, the research focus needs to shift from frontline service contexts. As such there have been multiple calls for the study of EL in more diverse contexts and in particular in professional level job roles (e.g., Harris, 2002; Humphrey et al., 2008; Tschan et al., 2005).

Emotional Labour and the HR Role

As part of the personnel manager’s emotional labour he has to learn the company’s ‘emotional map’. . . . He has to know where, along an accelerating array of insults, it becomes OK to take offence without too much counter-offence. He has to under-stand what various expressions ‘mean’ for a worker with a given biography, dispo-sition, reputation and status within the company. On an overlay map so to speak, he learns to trace patterns of emotional attribution (for example the secretaries may say their boss is mad today while his own boss doesn’t think so at all). (Hochschild, 1993, p. xi)

Empirical investigations of the emotional labour of HR practitioners though have not been forthcoming. This neglect could perhaps be due to the fact that while HR often involves a customer service orientation, it is a different kind of service role to that commonly discussed in the EL literature in that HR professionals generally do not deal with the public (with the exception of recruitment) and their ‘customers’ tend to be colleagues and other internal organizational constituents. Furthermore, unlike front-line service personnel whose work is generally scripted and monitored closely by supervisors to ensure compliance with organizational rules, HR practitioners have a large degree of autonomy in performing their role (Watson, 1977, 1986). In fact, given that EL is primarily conceptualized as the management of emotional expression in response to an organizationally mandated display (Hochschild, 1983), one could contend that it does not apply to HR professionals.

It has been argued however that EL is also performed in response to implicit norms and expectations of role holder behaviour (Ashforth and Humphrey, 1995), and in this regard it could be considered an aspect of HR work. HR is a functional role whose organizational power and influence is restricted and whose members are subject to multiple expectations, which inevitably influence and constrain practitioner behaviour (Truss et al., 2002). As Caldwell (2003) argues, the roles of HR professionals are ‘mirror images of shifting managerial perceptions, judgements and actions, over which personnel practitioners may have only limited influence’ (p. 1003).

HR practitioners’ working lives, and their behaviour including their emotional behav-iour, are very much constrained by contextual pressures. While research such as that conducted by Hiillos (2004) highlights that dealing with emotion is a central responsibil-ity of the HR practitioner, it does not explore the expectations for emotional expression associated with various HR roles. Nor does it explore how HR practitioners manage and control their own emotions to fulfil job requirements.

emotional display expectations. Thus we contribute to a contextualized elaboration of theory both about the HR role and EL in ‘backstage’ roles.

METHOD

This study is guided by the interpretivist view that reality is relative and multiple and that it is important to understand motives, meanings, reasons, and other subjective experi-ences which are time and context bound (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988). The goal is to connect the reader to the world of participants in order to facilitate an understanding of their subjective experience and illuminate the structures and processes that shape indi-viduals’ lives and their relations with others. The researcher is also historically and locally situated in the process being studied and thus knowledge is not value free (Denzin, 2001). Therefore any representational form should have enough ‘interpretative sufficiency’ (Christians et al., 1993, p. 120) – that is, possess depth, detail, nuance, and coherence to assist the reader in forming critical consciousness (Denzin, 2001). Here this means to give an interpretative portrayal of the emotional labour of HR professionals as perceived and experienced by role holders themselves and as told to and interpreted by researchers with experience in the HR field.

Through attending to the detail of participants’ language and accounts we hope to generate insights into their emotions and experiences and offer a counterpoint to many prescriptive accounts of the HR role which tend not to be grounded in role holders’ day to day experiences. By remaining analytically sensitive to how each individual’s account sheds light on their emotional response and the social context within which it emerges and is constructed, we provide theoretical insights about not only emotion and the HR role but also the dynamics of EL in backstage roles, an area not currently well understood.

Methods Employed

the data. A similar approach was taken by Harris (2002) in his study of the EL of barristers and was designed to provide insights into a framework of EL that is grounded in data but also informed by existing research. Our analysis and the concepts we derive from the analysis are influenced by extant theories both in the EL and HR role domains, however by attending to the detail of participants’ accounts and the language used we sought to ‘make the familiar strange’ (Spindler and Spindler, 1982 in Suddaby, 2006, p. 635).

Participants. Given the exploratory nature of the study and the need to understand the context of the research, non-probability sampling (also known as judgement or purposive sampling) was deemed appropriate for the current research (see Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Pratt, 2009). As Gummeson (1991) argues, unlike quantitative sampling, which is driven by the imperative of representativeness, qualitative sampling is concerned with thedepthandrichnessof data. A key issue within non-probability sampling is gaining access to ‘key’ informants whose knowledge and insights are crucial to understanding the phenomenon being researched (see Crimp and Wright, 1995). In the current case, and following the grounded theory approach, this meant that participants were gradually selected according to the expected level of new insights they could provide, the need to confirm/disconfirm propositions that had begun to emerge from initial interviews, and to ensure that interesting issues were further explored.

The first interview was conducted with a senior HR professional. This participant was asked to provide a list of other HR professionals of varying characteristics who may be interested and willing to take part in the study. In a snowballing effect each additional recruit was asked to generate a similar list of contacts. At the early stages of sampling the choice of participants was based on a need to get the perspectives of role holders with different characteristics (e.g., varying years of experience, from different organizational levels, across the main HR areas, male and female). As the study progressed, sampling was driven by the emerging propositions. For example, where a proposition arose that the negative consequences of EL may be offset by having other HR team members to confide in, an effort was made to recruit a participant who worked in a ‘lone’ HR role to see if they found engaging in EL more difficult and to uncover alternative coping strategies they may use.

Fifteen participants (six male; nine female) took part in the study; their HR experience ranged from 2 years to more than 15 years. They came from across the organizational levels (HR Vice-President – HR Specialist/Officer) and HR areas (Reward & Remu-neration; Training & Organization Development; Recruitment), and from a range of industry sectors, including Manufacturing, Pharmaceutical, IT, Leisure/Tourism, Food & Drinks, Public Sector, and Retail. While this choice of sample does not allow for an in-depth analysis of one particular HR specialism, it does give a flavour across the many levels and diverse aspects of the role.

In-depth interviews. Interviews lasting 60–90 minutes each were conducted with the 15 HR professionals. Five participants were interviewed on two occasions, generating a total of 20 interviews for the study. Emotion and emotional labour occur in the context of a personal narrative, history, present and anticipated future (Briner, 1999). Interviews were thus guided by the view that to understand emotion we need to know about the proximal event that triggered it, how the event came to have meaning, and what the consequences were. In a method similar to critical incident interviewing (Flanagan, 1954), participants were asked to give specific examples of workplace interactions. They were asked to describe the background and purpose of the interaction, who was involved, what happened, how they felt during and after, the emotions they displayed, and the outcomes. Where there was a discrepancy between felt and displayed emotions, further probes were used to understand the reason behind this. Interviews were taped and then transcribed for analysis purposes.

Diary measure – interaction records. The diary was based on the Rochester Interac-tion Record method (RIR; Nezlek et al., 1983) and followed methods used by Tschan et al. (2005). Following the first interview participants were asked to complete an ‘Interaction Record’ (IR) for interactions that lasted more than 10 minutes. Five par-ticipants completed the diary, with 28 IRs being returned. Those that failed to com-plete IRs stated that they could not find the time to do so. The IRs proved useful for producing examples of EL situations but the recorded data was ‘thin’. Examples given in the IRs were however explored during a second interview; in this way the recorded interactions were ‘brought to life’ and the IRs thus proved useful for reducing the retrospective elements of accounts. The data from the IRs was incorporated in the interview analysis process.

The above methods were deemed most appropriate given the limitations and prac-ticalities of the research context. Whilst the ideal may be to capture the ‘simmer and flow of everyday emotion’ (Fineman, 1993, p. 14) and to try and capture ‘real time’ emotion through the use of methods such as intensive ethnographies or participant observation, the highly sensitive and confidential nature of HR work as a research context meant that getting permission from all parties and access to employ such methods was not possible.

There are epistemological concerns regarding the ‘unknowability’ of emotion because it is often considered elusive, private, transient, and unmanageable (Sturdy, 2003). Many authors suggest that sometimes individuals do not know how they feel, do not understand their own emotions, or are not able to name their own feelings (e.g., Gerth and Mills, 1953), and this presents obvious problems for accessing emotion through report. Others highlight that emotions are often disguised to aid self-protection (e.g., Gabriel, 1999). Also, as Samra-Fredericks (2004) argues, the reliance on organizational members deploying a ‘language of emotion’ (Waldron, 1994) can obscure how expressions such as ‘makes me angry’ or ‘it’s so frustrating’ feed into split-second interactive routines.

difficult (but not impossible) to ‘fake’ accounts as did the use of questions about opposite cases (i.e., when participants did not comply, or felt a different way). These methods yielded interesting data not only on EL but on how the participants perceive, experience, and speak about their role.

Analysis. Transcripts were subjected to systematic analysis using techniques associated with the grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Strauss and Corbin, 1990).

In grounded theory research, data collection and data analysis are interrelated throughout the whole study, and unlike other methods where systematic analysis starts after all data is collected, the researcher is constantly moving between both processes. At the heart of the process is a ‘constant comparison method’ (Glaser and Strauss, 1967); instances of codes, concepts, and categories are continually compared with each other to highlight similarities and differences.

Analysis began with line-by-lineopencoding of each transcript. An initial list of codes was developed from the first interview and revised following analysis of subsequent interviews. Words and phrases used by the interviewee and deemed of importance to the research were given a short descriptor phrase or code. Codes that related to a common theme were grouped together into a concept using the constant comparison method, with in-vivo codes (words which were used by interviewees) being used where appropriate. Following open-coding, concepts were grouped together into categories. For example, codes in the ‘Rule Enforcer’ category included, amongst others, ‘toeing the line’; ‘correcting deviance’; ‘making others aware of standards’; and ‘rule enforcer’.

Concepts built from these initial codes included: communicating behavioural stand-ards to others, enforcing behavioural standstand-ards, and modelling behavioural standstand-ards. These concepts made up the eventual category of ‘Rule Enforcer’. This in-vivo code was deemed an appropriate one to use as a category as it captured the meaning of what was being described by participants. Each category was developed in this way by looking across incidences of occurrence and identifying concepts and sub-categories that could be brought together into one core category. This process is referred to by Strauss and Corbin (1990) as axial coding – the data is put back together in new ways by making connections between a category and its sub categories.

FINDINGS

The management of feeling and emotional expression to achieve an organizationally appropriate emotional display emerged as a central aspect of the HR role. Despite not working at the customer interface or in an environment where emotional display rules and scripts are explicitly laid out and compliance monitored by a manager, the HR professionals here felt restricted in their emotional repertoire and pressure to conform to the emotional display requirements of their job role. As one participant put it:

There are rules at play in that no matter what arrives at your door you don’t express horror you don’t express complete amazement you would have a fairly blank face but when you are finished having that conversation you could be absolutely appalled at what is after going on but you don’t display that, because if a person is complaining about another person there is always two sides to every story, so even if you’re appalled at what this person has told you, the other person could have a completely redeeming reason for what is happening, so you wear a mask and you don’t show your emotions. (P7: Female, HR Manager)

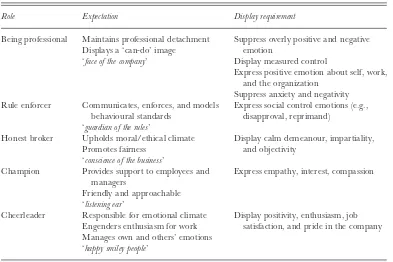

The rules for emotional expression derived from multiple sources including wider norms of professionalism, HR occupational norms, and the individual’s own expectations for the role. They drove organizational expectations of participants’ behaviour and were reinforced through feedback from peers and the application of sanctions in the case of divergence. Failure to conform was perceived as risking personal criticism, negative evaluation, and in some instances negative consequences for the organization such as legal action. Avoiding such consequences was a key influence on participant behaviour. In the course of our analysis light was shed on how HR professionals perceive and talk about their role, responsibilities, and corresponding behavioural and emotional display expectations; these are summarized in Table I.

While the dimensions of the HR role and associated emotion displays are presented as discrete categories in Table I, it is worth noting that participants might recount enacting any number of these roles and displays in an unfolding interaction. For clarity we now discuss each role and its display rules in turn.

Being Professional

You should remain neutral even though you know the person is wrong . . . you don’t want to get people’s back up. You should listen, observe and be non-judgemental. (P4: Female HRD Specialist)

These expectations are also exemplified by the quote below in which the participant describes another HR colleague whom she believes to be a highly effective ‘professional’:

I think that sometimes there is huge drama here but she would never get stressed about it, she would never scream at anybody, never raise her voice, she would never be rude to anybody, she would be very discreet, call someone into an office, just like I think somebody professional should behave. (P13: Female, HR Specialist, Recruitment)

There was a general belief that displays of unregulated emotion (and in particular extremes of emotion) would not only be seen by others as unprofessional but would lead to the impression of incompetence, something participants were keen to avoid. For example, the participant below described his ‘unprofessional’ reaction when the man-agement team would not agree to his proposal and the result of that reaction:

I got annoyed at the meeting and I turned round and said ‘I thought I was working with an enlightened group but obviously not’ and got really defensive, sat back in the chair folded my arms and said not very much just nodded at people. I suppose I was taking it personally, acting the way I did was not the professional response in my view.

Table I. HR roles and associated display expectations

Role Expectation Display requirement

Being professional Maintains professional detachment Displays a ‘can-do’ image

‘face of the company’

Suppress overly positive and negative emotion

Display measured control

Express positive emotion about self, work, and the organization

Suppress anxiety and negativity Rule enforcer Communicates, enforces, and models

behavioural standards ‘guardian of the rules’

Express social control emotions (e.g., disapproval, reprimand)

Honest broker Upholds moral/ethical climate Promotes fairness

‘conscience of the business’

Display calm demeanour, impartiality, and objectivity

Champion Provides support to employees and managers

Friendly and approachable ‘listening ear’

Express empathy, interest, compassion

Cheerleader Responsible for emotional climate Engenders enthusiasm for work Manages own and others’ emotions ‘happy smiley people’

. . . I got feedback from my manager to say I got defensive in the meeting which didn’t really help. (P1: Male, HR Vice-President)

In this situation the individual showed his genuine negative emotions of frustration and annoyance, however he felt his behaviour was inappropriate and he describes showing his emotions as taking it ‘personally’ and getting ‘defensive’, which is not the ‘profes-sional’ thing to do. This was in turn reinforced by the negative feedback he received from his manager. Integral to this view is that to be seen as competent and in control he is required to manage his own emotional display and indeed his feelings.

It appears that the powerful appeal of the discourse of professionalism is evoked and mobilized instrumentally by managers through organizational talk (e.g., ‘don’t get defen-sive’) and practices (e.g., feedback on inappropriate behaviour) to achieve organizational goals. High value is placed on the capacity to deliver what is required regardless of one’s personal values and feelings, and the needs of the company are invoked as super-ordinate. This pressure to conform to the professional ideal and to avoid the negative consequences of non-conformance drove many EL performances. In fact, it appeared that performing EL was critical to behaving professionally.

The findings above are consistent with Sachs and Blackmore (1998), who found in their interviews with workers, that being a ‘professional’ was code for being able to appropriately control one’s emotions. They also reflect much organization theory around professionalism (Martin et al., 1998) which emphasizes rationality and down-grades emotion and mirror anecdotal evidence that emotional detachment is equated with rational competence ( James, 1993), and emotional control is highly conducive to an individual’s corporate success (Harris, 2002; Jackall, 1988).

The emotion display rules associated with being professional were not seen as organizationally specific nor were they viewed as specific to the HR role. Rather they were deemed part of the general rules that need to be followed to ensure positive relationships at work and career success. Participants did however feel that the pressure to conform to these display requirements was more intense for those working in HR because of the nature of HR work and the particular role they occupy in the organiza-tion, as illustrated in the quotes below:

It just comes with the job and if you feel pissed off or having a bad day or frustrated people say ‘oh god, Jesus you’re very, very stressed today what’s wrong with you’ like you’re not entitled to have a bad day whereas if I was in another department people would think ‘oh she’s under pressure, she must have a big project on’, there’s leeway for them but none for us. (P5: Female, HR Generalist)

I think people put HR into a box or onto a platform, people nearly expect people in HR not to have a sense of humour, not to let their hair down, you know you are in HR, you should be the company . . . I suppose the bar is raised that’s the nature of it. (P12: Female, HR Director)

their credibility with other management groups. The findings here suggest that concerns with demonstrating credibility and value still echo within the HR profession. Participants were not only concerned about the negative effect of non-conformance on their own professional image but were aware that as a representative of the HR profession how they behave during interactions can affect employees’ and other stakeholders’ feelings about the integrity and credibility of the HR role:

you are aware yourself that people are looking at you, they are making value judge-ments about you and your profession, particularly because HR isn’t seen as the value-added entity, you are determined to prove that worth and that value of your profession. (P14: Female, HR Manager)

The HR Director below explains that HR professionals must always wear a ‘mask of professionalism’ because they are the ‘face of the company’. They represent the company when dealing with employees in an emotional state and the ramifications of letting the mask slip can be serious:

HR is seen as the interface with the company, they are part of the company but if it is being ‘done onto them’ or if it’s retirements its HR people standing up, it should be their line manager or someone that deals with them on a day-to-day basis, but if you are representing the company on pay increases or if you’re standing in front of the labour court you are representing the company so you have to have an affiliation with an entity that doesn’t have a face, you are it. (P6: Male, HR Director)

The HR professional is the embodiment of the organization who is expected to become not only the face of the company, but the heart of it also. In fulfilling such expectations the role holder feels a pressure to wear a mask even when it doesn’t seem to fit. At times this can leave them struggling to reconcile how they feel with the expected display, as the following quotes demonstrate:

I suppose part of me felt my heart wasn’t in it but you know you still wore the company hat and followed it through. . . . It was hard, I felt it was hard to be real. (P11: Male, HR Manager)

I suppose if you are suppressing one emotion such as anger and you’re trying to display another emotion, sincerity, there is a mismatch and that’s not going to be congruent in coming across. (P8: Male, HR Manager)

professionalism is often associated with a lack of emotion (in favour of rationality), here we see that enacting a professional demeanour can involve significant feats of emotional labour. In fact, it seemed that the requirement to be ‘professional’ was a baseline role upon which all the other HR roles sat. As such, professionalism operated as a key driver for all of the recounted EL performances and interactions. However, additional role expectations were layered on top – ‘the bar is raised’ – for the model HR professional, creating further EL requirements that are specific to HR work. We now turn to these.

Rule Enforcer

A central part of the HR role is to specify and communicate the values, ethos, and behavioural standards of the company. Participants described an expectation for them to be a ‘rule enforcer’ and ‘the guardian of the rules’:

I suppose the other rule is to be the guardian of the rules. . . . in many ways it can be the perceived image of the organization you know what I mean and I suppose you’re acting as conduit between the organization and the employee and from that point of view there is expectations on both sides which may not be the same. (P8: Male, HR Manager)

They talked about the need to maintain and reinforce acceptable standards of behaviour in relation to discipline and organizational policies such as absenteeism or equal oppor-tunities. Fulfilling this expectation often meant suppressing felt emotions in favour of a mandated display which included the expression of social control emotions such as disapproval or reprimand. For example, the participant in the excerpt below had described feeling angry and frustrated when a colleague (a senior manager) jeopardized a disciplinary hearing by not following the script that they had previously agreed upon. The manager made personal comments about the employee’s appearance and the employee subsequently complained to the shop steward:

a manager was in the wrong and you have to be seen to . . . let that manager know exactly that, clearly what happened was unacceptable. I could display anger in my tone. . . . I would have been slightly more formal than previous meetings and my tone would have been sharper and the displeasure would have been noted. . . . it was controlled. (P6: Female, HR Manager)

This role holder described feeling a certain amount of empathy for the manager who acknowledged messing up. In this situation she deemed it appropriate to display the negative emotions of anger she felt but in a controlled way to ensure the ‘offender’ knew he had done wrong. The rule enforcer role also extended to ensuring others managed their emotional displays in an acceptable way as the following excerpt demonstrates:

trying to have them react in a more conservative way, take a breath. (P2: Male, HR Manager)

Having to maintain and indeed model the ‘ideal’ standard of behaviour that all employees must aim to reach inevitably influenced many EL performances:

if we are the ones driving the policies and that stuff you have to be seen to toe the line, if you are not going to let anyone else fall outside the policies you can’t do it yourself. (P3: Female, HR Specialist, Compensation & Benefits)

Although participants bought into this role demand there was a certain element of oppression and an air of cynicism around the impossible requirement to be perfect. This is evident from the quote below in which the participant describes how the need to maintain emotional control was relayed to her by her manager:

‘manage your state please’ you know you had to completely manage your ‘state’ not even use [the term] emotions it was described as manage your state at work, it was over-played and totally ridiculous. (P13: Female, HR Specialist, Recruitment)

These findings highlight that, reminiscent of Storey’s (1992) regulator and aspects of Tyson and Fell’s (1986) clerk of works roles, participants believe that ensuring compli-ance to organizational rules is a key element of their work. This casts doubt on whether Ulrich’s (1997) recommendation that HR must move beyond their conventional role of policy police and regulatory watchdog, has actually been realized. The compliance aspect of the HR role, while a very important dimension (both in practice and in many typologies), complicates other dimensions. For instance, the expectation to enforce rules positions HR role holders as an instrument of management control in ensuring no-one ‘fell outside the rules’, but as we will see later, participants also saw themselves as having a special relationship with employees and championing their needs. The multi-faceted nature of the role creates challenges for participants’ EL. For example, as we will see below, the need to engage in displays of social control emotions does not sit easily with displays of calm neutrality associated with being an ‘honest broker’ or displays of empathy associated with the ‘champion’ role.

Honest Broker

Participants spoke of having to follow due process and be objective and non-judgemental regardless of their own thoughts and feelings in dealing with workplace problems. They described HR as the ‘conscience of the business’ and the ‘honest broker’ with a respon-sibility for ensuring transparency in decision-making processes and engendering feelings of trust:

They were cognizant of the possible ramifications of their behaviour for themselves and the organization (e.g., risk of labour court proceedings; what they do can set a precedent for the future). The HR manager below highlighted this point when talking about a disciplinary meeting regarding an employee’s performance:

the game is based on factual information, and what happened and when and where and what actions were taken as a result so that in a sense the issues should be judged about the facts not how you feel about the facts so that in a sense if you display emotion regarding it then it comes out in an emotional way then it becomes a personalized issue and you can’t afford for it to be a personalized issue. I think in a situation like that the process is always more forgiving of a manager because with HR, within the HR role, the onus is on HR to be the guardian of that fairness. (P8: Male, HR Manager)

Additionally there was a belief that responsibility for the organization’s ethical and moral climate lay firmly at the door of the HR function and that HR professionals themselves should be beyond reproach when it came to their behavioural displays:

A HR person has to be super-human, cleaner than clean, there is an expectation, at least I felt it, that you have to be beyond reproach and honest to the core because if you’re not who else is going to be? So there is a certain amount of standards enforced, it’s down to someone’s personal disposition in so far as no-one is 100% squeaky clean but you say as you do and do as you say. (P6: Male, HR Director)

This expectation to be an independent ‘honest broker’ in negotiating the employment relationship bears similarity to Storey’s (1992) contracts manager role and is under-pinned by occupational values of impartiality, neutrality, and fairness. Fulfilling this role required participants to control their emotion in order to remain calm and to be ‘middle of the road’:

you don’t show your emotions, you wouldn’t be middle of the road [if you did] show your emotions then that person would be able to say this is great she’s on my side now. (P7: Female HR Manager)

Highlighted here is the relational nature of the HR professionals’ emotional labour. Participants were not only concerned about the organizational consequences of their behaviour and decisions, they were acutely aware of the potential impacts on working relationships and future interactions they may have with the interaction partner. Thus they managed their emotions to ensure the maintenance of these relationships as the following quote demonstrates:

We can already see the complexity of requirements in terms of emotional display norms and role enactment. A simplistic division of paternalistic care of employees versus control of staff behaviour is untenable. The control dimension applies as much, if not more, to the HR professional (‘has to be super-human’) as it does to other employees. Moreover the need to give controlled emotional displays (as a listening ear, the public face, being beyond reproach) functions in a variety of ways – to fulfil personal/professional stand-ards for the role, to boost credibility with other organizational stakeholders, to legitimize one’s position in external facing roles (‘the public face’), and perhaps most importantly to induce a particular kind of emotional response from the interaction partner, which of course is at the core of emotional labour. Role holders felt the need to ensure the other person in the interaction felt the process was fair and the outcome deserved and just, rather than feeling hostile, defiant, or angry. Control through a display of caring (whether that was authentic or not).

Champion

The HR professionals in this study were acutely aware of the organizational audience (i.e., employees, line managers, senior management team) and their varying and some-times conflicting expectations of the HR role provider. They described how employees expected them to attend to their needs and promote their welfare – to be the ‘employee champion’. To meet this expectation they felt they needed to be ‘approachable’ and friendly – a people person. To show empathy and interest towards the employee and to hide any negative feelings of irritation or annoyance as the following quote demonstrates:

you know people have this kind of idea [about HR] sure you’re looking out for employees and looking after people, and sometimes a bit of madness takes over . . . someone comes in to tell you their troubles and part of you is like ‘I care because’? . . . but you can’t show that, you have to wear a mask. (P12: Female, HR Director)

From a management or organizational perspective, providing empathy and a ‘listening ear’ to employees was accepted as part of the remit of a HR professional, but only under the provision that organizational interests are protected at the same time:

With employees you are an employee champion and I don’t mean that in a big sense but you are theirs, they expect you to treat them with fairness and respect. And from a manager’s point of view, the organizational point of view, that is the case as well but you do it with minimum cost and minimum interference. (P2: Male, HR Manager)

To add to the complexity of this role, being a champion also meant providing counsel to managers in dealing with issues that arose in managing employees and to facilitate problem-solving, to be on the manager’s side and champion their cause:

right way? you need to have a good working relationship with . . . [you] have to control it [emotion]. (P10: Female, HR Manager)

In some situations, as will be discussed later, managers’ and employees’ interests and needs conflicted and trying to champion both often left participants confused about which emotional display was appropriate and where their allegiance should lie.

The champion role here bears similarities to Ulrich’s conceptualization in that par-ticipants perceived themselves to be representatives of employees. HR professionals are however also required to champion managers and protect organizational interests, in Ulrich’s terms, to deliver value based on economic criteria. Our findings revealed that the welfare aspect of this dual role is more dominant than that implied in Ulrich’s conceptualization and the strength of the role holder’s desire to protect employees can create difficult emotional challenges.

Cheerleader

Participants perceived an expectation for them to act as ‘cheerleaders’ which goes beyond the caring aspects of the champion role described above. The cheerleader role required them to promote job satisfaction, boost employee morale, and engender com-mitment to the company. The emotion display expectations involved proactively helping to keep employee spirits up and promoting positivity in the organization. This respon-sibility was seen as preventing the HR role holder from ‘whingeing’ or being negative in their interactions with employees and inevitably drove them to hide any feelings of job dissatisfaction or frustration they may experience themselves. Maintaining this pretence was considered stressful and difficult but an essential requirement of the job:

I find it difficult to keep up the pretence, you couldn’t let your guard down, HR are the happy smiley people, we are always happy and obliging and ready to help. (P5: Female, HR Generalist)

Another HR manager explained why, in a difficult time of change and redundancies within the company, even though she was under threat of redundancy herself, she couldn’t display the genuine emotions she was feeling:

I suppose with that position because of all these other people around you had to be strong you couldn’t panic, they couldn’t see you panicking, I was the HR person you had to take it your stride you have to be normal, for other people you had to try and remain calm. (P14: Female, HR Manager)

community and positivity amongst the workforce did appear to come from a position of ensuring positive work outcomes but was underpinned by a genuine concern for employee needs and well-being.

By examining HR staff accounts of the emotional labour required to balance organizational and employee needs we glimpse interesting insights into the dynamics of employment relations. It is to that dynamic we turn next by exploring in more detail the tensions between the various roles.

Tension between the roles. Participants described many situations where they found them-selves oscillating between the caring and control aspects of HR. This dilemma was vividly referred to as the ‘Two Hats of HR’. This exposed the tension between poten-tially incompatible sets of expectations. As one participant put it, HR is the ‘man in the middle’ caught between the differing expectations about HR allegiances. At times these emerged as intra-category tensions; for example, being the ‘champion’ required role holders to display empathy and to pay attention to the needs and aspirations of employees, but it also required them to support managers and empathize with them in their dealings with employees. There are also instances of inter-category tensions; for example, enacting the ‘rule enforcer’ role required participants to adhere to organizational policy and display social control emotions, whereas the cheerleader role demanded that they display positivity and enthuse employees. The ‘honest broker’ role required them to display neutrality and calm objectivity, which can be difficult to reconcile with displaying empathy as an employee champion, or indeed positivity as the cheerleader.

The difficulty in deciding how to play a situation and dealing with conflicting expec-tations was a recurring theme. In the following situation, the role holder struggles with conflicting emotions evoked by an interaction where he had to dismiss an employee. He described how he felt:

Well a conflict because on one hand I have to feel sympathy for this individual I have sympathy for the situation they find themselves in, I have sympathy in terms of procedure and process if you think about what is the right course of action, but on the other hand if you think about the company and the company name and trying to ensure as little damage within the company and externally to the company because in HR you’d always be looking at you are a guardian of the company and the company name but you also have to champion the employee. (P1: Male, HR Vice-President)

In this situation, as with most similar situations described by participants, the company hat won out, a desire to follow procedure and process overruled the feelings of empathy for the employee but the participant described how dealing with such interactions was ‘very draining’; and how this affects subsequent interactions: ‘you are certainly not giving it [the next thing] any degree of attention that it deserves’. Such multiple, and at times conflicting, emotional display requirements can clearly have negative consequences for back stage staff.

employment contract, with those not willing/able to conform being subject to negative feedback and sanctions. However, by evoking ideal HR attributes, organizational display rules appeal to a professional identity which the individual has been inducted into through occupational socialization and which they are motivated to protect. HR professionals’ EL may not be subject to the same degree of ‘scripted’ regulation as frontline service staff; rather they are self-policing and self-regulating in relation to organizational rules for emotion display. This is because these rules build on both occupational and role holders’ expectations of what it is to be an HR professional.

These findings are of course bounded by the study limitations. The account given here, like all social scientific accounts, is a highly selective and shaped piece of writing (Atkinson, 1990; Watson, 2000) chosen from lengthy interviews. As such what is pre-sented is a contestable social construction (Craib, 1997) and it is acknowledged that the inquirer and the inquired into are interlocked (Al Zeera, 2001). Thus the findings reflect the researcher’s individual perceptions of what is important and what is reality. Also, we cannot generalize about what all or even most HR professionals do or think on the basis of 15 participants, nor was it the intention here to do so.

This paper does not claim to have tapped the entire domain of potential factors that surround emotion and the HR role. The strength of the study lies in the depth of the data gathered about specific interactions. Participants were encouraged to recall and com-municate as depth-fully as possible their experience of thinking, feeling, and behaving. This process elicited a richly nuanced picture of what it meant to the individual to experience that particular situation, and there is enough interpretative sufficiency (Denzin, 2001) to connect the reader to the world of participants. Further research could examine the ‘weight’ of the roles identified by our study for HR practitioners and whether patterns of EL differ depending on factors such as hierarchical level, specialism, organization, or sector.

DISCUSSION

Implications for Understanding the HR Role

In terms of the HR role, attending to participant accounts of EL brings a richer perspective than that provided by normative models, which may capture variety inherent in the role but downplay the challenges and specifically the emotional challenges that enacting the role creates. Our participants, for example, were acutely aware of the behavioural and emotional display expectations held by others and played the HR role accordingly (despite how they may really have felt) to achieve task goals and maintain effective working relationships. This not only suggests, similar to Truss et al. (2002), that the roles HR professionals play are contextually embedded and locally negotiated between practitioners and stakeholders, it highlights that creating complex EL perfor-mances is an integral aspect of such roles.

Our findings also suggest that the duality and ambiguity in HR work, originally highlighted by Legge and Watson more than 30 years ago, persists and that emotion management is central in handling the dilemmas that arise out of this duality. Partici-pants felt they should advocate for employees but they also had a strong need to protect their own image and that of the HR function as a valuable contributor to bottom line results. These dual expectations had the potential to evoke intense mixed emotions in role holders and they worked to find a balanced and optimal course of action that satisfied all constituents. This reinforces the view that the HR function is vulnerable to negative images and HR practitioners are still concerned with their status, legitimacy, and credibility (e.g., Caldwell, 2003; Farndale and Brewster, 2005; Legge, 2005); and suggests that appropriately managing emotion is pivotal in this image maintenance process.

Furthermore, while some analysts argue that HR professionals have abandoned employees in the attempt to enhance their own position vis-à-vis management (Peterson, 2004), our analysis suggests thatboththe social values of personnel management and the economic values of HRM shape expectations about how the HR role should be played. Here we see the tough choices that confront the human agents who enact HR policy. How HR ‘is done’ in practice is the outcome of ‘human interpretations, conflicts, confusions, guesses and rationalisations’ (Watson, 2004, p. 458), all of which are emo-tionally charged and operate within the constraints of what is expected by stakeholders. In contrast to the sometimes simplistic discourses (as noted by Watson, 2004) about choices between ‘caring’ or ‘control’ and ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ models and practices of HRM, using the lens of emotion we see that HR professionals must give layered performances of ‘hard and soft’ and ‘caring and control’. There are complex and subtle interplays between caring, control, and many other emotion displays; for example, achieving control through an insincere but effective display of caring, or genuinely feeling empathy yet displaying neutral emotions to maintain a stance of objectivity in an interaction. Focusing on emotion reveals both the personal struggle in reconciling ‘caring and control’, and also the inherent tensions between business and humanistic values in employment relationships.

present in the interaction and the possible outcomes for the organization, the employees, and the HR practitioners themselves. Thus their role was a shifting one; at times participants acted more as a representative of the employer and at other times they were more on the employee side. By using language such as ‘display’, ‘role’, and ‘performance’ we are not however suggesting a moral levity and latitude in HR professionals’ role enactment. From our participants, there is a palpable sense that HR practitioners struggle to produce displays that are answerable both to their own values and to those of other stakeholders. Thus the defining feature of EL as stemming from a disjunction between the ‘ought’ and the ‘is’ applies to more than just emotion display; it also applies to values in employment relationships. Interestingly, while Harris (2002) suggested that the EL of ‘status’ professions (e.g., barristers) could be differentiated from occupational professions such as engineers, accountants, or HR, by a commitment to serve a greater good, we see echoes of such concerns here with HR professionals’ EL being driven in part by serving the needs of the organization but also by what they deem ‘is right’ for employees. This may derive from two interacting factors: (i) historically, the welfare roots of personnel management; and (ii) a contemporary process of an occupational profession seeking to increase its status via the appropriation of status professions’ discourses about professional concerns for a self-regulating code of practice and sense of a higher purpose (beyond a given task or job).

Such a picture contradicts analyses of HR work, which suggest that the role of HR professionals is becoming predominantly driven by economic and business values. Rather, our findings support the more pluralist perspective of Paauwe (2004) and others (e.g., Caldwell, 2003; Francis and Keegan, 2006) and the empirical work of Ramsay et al. (2000) that suggest that the economic side of organizing and the human side of organ-izing sometimes coincide and sometimes conflict. Our study shows both variety and contradiction in HR roles and supports Caldwell’s (2001, pp. 39–53) assertion that HR managers in the ‘real world’ have to live with overlapping, conflicting, and sometimes confusing roles and must blend ‘old’ and ‘new’ roles. We add that this ambivalence creates intense emotional challenges for the practitioner, a point that HRM models tend to ignore but if acknowledged, could develop our understanding of role realities.

Implications for Emotional Labour

In terms of EL, our work makes a contribution to the comparatively under-researched but growing recognition of EL in professional/backstage work.

The question then is raised – do back- and front-stage EL warrant different conceptualizations? Contextual factors potentially make the backstage EL of HR pro-fessionals different and more complex than that of frontline service workers. For instance, unlike many front-stage roles, HR professionals’ EL is largely unscripted. Display rules for the HR role are ambiguous, implicit, and rarely addressed in organizational training/induction, and they also derive from multiple sources rather than just being prescribed by management. Also, unlike the service context where EL is generally performed in a highly repetitive fashion using a narrow range of emotions (Humphrey et al., 2008), HR role holders have to display a wide variety of emotions depending on the particular situation. For instance, in the customer service environment the expectation is generally to promote a positive emotional state – that is, ‘keep the customer happy’ (Hochschild, 1983); HR professionals however are expected to produce feelings of trust, integrity, and fairness. They do this in situations where ‘customers’ may feel their job or professional reputations are under threat (e.g., in performance manage-ment or disciplinary situations). They may be dealing with trade union officials who inherently distrust HR as ‘the face of the company’ and are trying to move the interac-tion partner from a posiinterac-tion of trust deficit rather than neutrality. Under some circum-stances (e.g., redundancies) the HR role holder may even be subject to the same personal anxieties as the interaction partner because their own job may be under threat. Such situations are far removed from the delivery of ‘service with a smile’ (Leidner, 1993) and the stakes are likely to be higher for both the organization (e.g., industrial unrest, legal action) and the individual (e.g., sanctions such as discipline or dismissal) if an appropriate display is not achieved.

To add to the above complexity, EL in HR work is also likely to be performed in a context of ‘high strength’ relationships (Groth et al., 2004). Unlike the frontline where interactions are likely to be ‘low strength’ one-off encounters, HR professionals are likely to have a relationship, a shared history, and expectation of future interac-tions with the EL target. The norms for long-term relainterac-tionships, as Argyle and Henderson (1985) note, often contain a requirement to be honest, and if the interac-tion partner detects that emointerac-tion is fake it can have detrimental consequences. This can make achieving the appropriate display more onerous than one-off service encoun-ters. Furthermore, unlike service personnel who tend to have low to moderate role identification (see Humphrey et al., 2008), HR role holders are likely to view their work as an integral part of themselves, and not living up to the perceived demands of that role can have negative impacts on self-esteem. So while at times EL was per-formed for the benefit of the organization, it was also agentively perper-formed to achieve task and personal goals. This contrasts with the dominant view in the service literature that EL is an example of exploitation and the employee’s passive compliance with the organizational mandate (e.g., Ashforth and Humphrey, 1993; Constanti and Gibbs, 2005; Hochschild, 1983).

front-line, such as nurses and police officers (Wolkomir and Powers, 2007). HR profes-sionals on the other hand have more autonomy and scope to regulate their own emotion management.

Such context differences may indeed suggest that EL is fundamentally different in the back and front stage. An alternative view is that perhaps some of the aspects of EL that have emerged here as a result of looking at the backstage environment may also operate front stage. Researchers, blinkered by a negative view of EL, may have missed the role of individual agency, the influence of forces external to the organization (such as pro-fessional norms, occupational ideals, and the individual’s own expectations for the role), and the possible benefits of performing EL for the individual (such as a sense of self-efficacy and esteem from living up to a role with which one identifies). This suggestion is bolstered by recent research in a service environment (Ashforth et al., 2008), which found that rather than acquiescing with display rules, service agents proactively engage in EL to control service encounters, steering the direction and emotional tone of the interaction. This more dynamic view of EL has however yet to find its way into conceptualizations of EL in the service context. Perhaps by reviewing front-stage EL under refracted light from backstage research, we may see a more multi-dimensional phenomenon.

In addition to implications for front-stage EL, our findings support and extend pre-vious research in the backstage domain which has highlighted the difficulty of ascribing the performance of EL to one single variable in the organizational context, such as management control through prescriptive display rules (see, e.g., Bolton, 2000; Harris, 2002; Ogbonna and Harris, 2004). For example, Ogbonna and Harris (2004) identified that occupational as well as organizational expectations could drive lecturers’ emotional labour. Our novel contribution is to show variety within the categories of occupational and organizational expectations and thus attendant variety in the emotion displays required. Sources of variety stemmed from, for example, which stakeholders are involved in the encounter, and what the interests of stakeholders may be relative to the issue at play, and thus which occupational expectations were prioritized – for example to be rational and detached and suppress emotion in one situation or to demonstrate empathy in another. We also extend Harris’ (2002) work, where the rules for barristers’ emotion displays – while often challenging and complex – did not appear to be contradictory. We would attribute the contradictions in HR professionals’ EL in part to ambiguities in the HR role (as discussed earlier – whose interests they ought to serve), and in part to the lack of explicit training and socialization in what ought to be done/displayed – in stark contrast to the barristers in Harris (2002) who had lengthy apprenticeships with ‘pupil masters’ in order to perfect the right ‘demeanour’.

So whilst the current study has contributed to our understanding of EL in the backstage context, further research is clearly needed. In particular, exploring the variety of ways employees conform to, resist, or indeed embrace organizational controls and the related identity construction and management processes, may offer a more rounded view of the EL construct in both the back- and front-stage contexts.

political context (Watson, 2004). They face a precarious balancing act of representing employee needs and implementing a business agenda, while at the same time attempting to maintain a trusting working relationship with employees and an image of competence and credibility in the eyes of line and senior managers. Our study suggests that handling the emotions that work situations prompt and creating the appropriate emotional display is central to successfully achieving this balance. Watson (1986) once suggested that ‘to watch a personnel manager operating over a period of time is to go through a process of constantly wondering whether one is seeing the wielding of an iron fist in a velvet glove or a velvet fist in an iron glove’ (pp. 180–83). This image vividly portrays the role dilemmas of caring versus control, but based on our research does not capture fully the realities of more nuanced HR performances which might be more accurately portrayed as the improvising actor hiding their emotions behind the many masks expected by their audience, even when such masks do not seem to fit.

REFERENCES

Al Zeera, Z. (2001). Wholeness and Holiness Education: An Islamic Perspective. Herndon, VA: International Institute of Islamic Thought.

Argyle, M. and Henderson, M. (1985). ‘The rules of relationships’. In Duck, S. and Perlman, D. (Eds), Understanding Personal Relationships. London: Sage, 63–84.

Ashforth, B. E. and Humphrey, R. H. (1993). ‘Emotional labour in service roles: the influence of identity’. Academy of Management Review,18, 88–115.

Ashforth, B. E. and Humphrey, R. H. (1995). ‘Emotion in the workplace: a reappraisal’.Human Relations,48, 97–125.

Ashforth, B. E., Kulik, C. T. and Tomiuk, M. A. (2008). ‘How service agents manage the person–role interface’.Group & Organization Management,33, 5–45.

Ashkanasy, N. M. (2002). ‘Studies of cognition and emotion in organisations: attribution, affective events, emotional intelligence and perception of emotion’.Australian Journal of Management,27, 11–20. Ashkanasy, N. M. and Daus, C. S. (2002). ‘Emotion in the workplace: the new challenge for managers’.

Academy of Management Executive,16, 76–86.

Atkinson, P. (1990).The Ethnographic Imagination: Textual Construction of Reality. London: Routledge.

Barsade, S. G., Brief, A. P. and Spataro, S. E. (2003). ‘The affective revolution in organisational behaviour: the emergence of a paradigm’. In Greenberg, J. (Ed.),OB: The State of the Science, 2nd edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 3–52.

Becker, B. and Huselid, M. (1998). ‘High performance work systems and firm performance: a synthesis of research and managerial implications’.Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management,16, 53–101. Bolton, S. (2000). ‘Who cares? Offering emotion work as a “gift” in the nursing labour process’.Journal of

Advanced Nursing,32, 580–6.

Bolton, S. and Houlihan, S. (Eds). (2007).Searching for the Human in Human Resource Management: Theory, Practice and Workplace Contexts. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Briner, R. B. (1999). ‘The neglect and importance of emotion at work’. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology,8, 323–46.

Brotheridge, C. and Grandey, A. (2002). ‘Emotional labor and burnout: comparing two perspectives of “people work” ’.Journal of Vocational Behavior,60, 17–39.

Brotheridge, C. and Lee, R. T. (2003). ‘Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labour’.Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,7, 57–67.

Caldwell, R. (2001). ‘Champions, adaptors, consultants and synergists: the new change agents in HRM’. Human Resource Management Journal,11, 39–53.

Caldwell, R. (2003). ‘The changing role of personnel managers: old ambiguities, new uncertainties’.Journal of Management Studies,40, 983–1005.

Caldwell, R. and Storey, J. (2007). ‘The HR function integration or fragmentation’. In Storey, J. (Ed.), Human Resource Management: A Critical Text, 3rd edition. London: Thomson Learning, 21–38.