PROFESSIONAL

JAVASCRIPT

®

FOR WEB DEVELOPERS

FOREWORD . . . xxxi

INTRODUCTION . . . xxxiii

CHAPTER 1 What Is JavaScript? . . . 1

CHAPTER 2 JavaScript in HTML . . . .13

CHAPTER 3 Language Basics . . . 25

CHAPTER 4 Variables, Scope, and Memory . . . 85

CHAPTER 5 Reference Types . . . 103

CHAPTER 6 Object-Oriented Programming . . . 173

CHAPTER 7 Function Expressions . . . 217

CHAPTER 8 The Browser Object Model . . . 239

CHAPTER 9 Client Detection . . . 271

CHAPTER 10 The Document Object Model . . . 309

CHAPTER 11 DOM Extensions . . . 357

CHAPTER 12 DOM Levels 2 and 3 . . . 381

CHAPTER 13 Events . . . 431

CHAPTER 14 Scripting Forms . . . 511

CHAPTER 15 Graphics with Canvas . . . 551

CHAPTER 16 HTML5 Scripting . . . 591

CHAPTER 17 Error Handling and Debugging . . . 607

CHAPTER 18 XML in JavaScript . . . 641

CHAPTER 19 ECMAScript for XML . . . 671

CHAPTER 20 JSON . . . 691

CHAPTER 21 Ajax and Comet . . . 701

CHAPTER 22 Advanced Techniques . . . 731

CHAPTER 23 Offl ine Applications and Client-Side Storage . . . 765

APPENDIX C JavaScript Libraries . . . 885

APPENDIX D JavaScript Tools . . . 891

PROFESSIONAL

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

PROFESSIONAL

JavaScript

®

for Web Developers

Third Edition

Indianapolis, IN 46256

www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2012 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana

Published simultaneously in Canada

ISBN: 978-1-118-02669-4 ISBN: 978-1-118-22219-5 (ebk) ISBN: 978-1-118-23309-2 (ebk) ISBN: 978-1-118-26080-7 (ebk)

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifi cally disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fi tness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for every situation. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. The fact that an organization or Web site is referred to in this work as a citation and/or a potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organization or Web site may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that Internet Web sites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read.

For general information on our other products and services please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (877) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at

http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011943911

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

NICHOLAS C. ZAKAS has been working with the web for over a decade. During that time, he has worked both on corporate intranet applications used by some of the largest companies in the world and on large-scale consumer websites such as My Yahoo! and the Yahoo! homepage. As a presentation architect at Yahoo!, Nicholas guided front-end development and standards for some of the most-visited websites in the world. Nicholas is an established speaker and regularly gives talks at companies, conferences, and meetups regarding front-end best practices and new technology. He has authored several books, including Professional Ajax and High Performance JavaScript, and writes regularly on his blog at http://www.nczonline.net/. Nicholas’s Twitter handle is @slicknet.

ABOUT THE TECHNICAL EDITOR

CREDITS

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Carol Long

SENIOR PROJECT EDITOR Kevin Kent

TECHNICAL EDITOR John Peloquin

PRODUCTION EDITOR Kathleen Wisor

COPY EDITOR Katherine Burt

EDITORIAL MANAGER Mary Beth Wakefi eld

FREELANCER EDITORIAL MANAGER Rosemarie Graham

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF MARKETING David Mayhew

MARKETING MANAGER Ashley Zurcher

BUSINESS MANAGER Amy Knies

PRODUCTION MANAGER Tim Tate

VICE PRESIDENT AND EXECUTIVE GROUP PUBLISHER

Richard Swadley

VICE PRESIDENT AND EXECUTIVE PUBLISHER

Neil Edde

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Jim Minatel

PROJECT COORDINATOR, COVER Katie Crocker

PROOFREADER Nicole Hirschman

INDEXER Robert Swanson

COVER DESIGNER LeAndra Young

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EVEN THOUGH THE AUTHOR’S NAME is the one that graces the cover of a book, no book is the result of one person’s efforts, and I’d like to thank a few of the people involved in this one.

First and foremost, thanks to John Wiley & Sons for continuing to give me opportunities to write. They were the only people willing to take a risk on an unknown author for the fi rst edition of Professional JavaScript for Web Developers, and for that I will be forever grateful.

Thanks to the staff of John Wiley & Sons, specifi cally Kevin Kent and John Peloquin, who both did an excellent job keeping me honest and dealing with my frequent changes to the book as I was writing.

I’d also like to thank everyone who provided feedback on draft chapters of the book: Rob Friesel, Sergey Ilinsky, Dan Kielp, Peter-Paul Koch, Jeremy McPeak, Alex Petrescu, Dmitry Soshnikov, and Juriy “Kangax” Zaytsev. Your feedback made this book something that I’m extremely proud of.

A special thanks to Brendan Eich for his corrections to the history of JavaScript included in Chapter 1.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD xxxi

INTRODUCTION xxxiii

CHAPTER 1: WHAT IS JAVASCRIPT? 1

A Short History

2

JavaScript Implementations

3

ECMAScript 3

The Document Object Model (DOM) 6

The Browser Object Model (BOM) 9

JavaScript Versions

10

Summary 11

CHAPTER 2: JAVASCRIPT IN HTML 13

The <script> Element

13

Tag Placement 16

Deferred Scripts 16

Asynchronous Scripts 17

Changes in XHTML 18

Deprecated Syntax 20

Inline Code versus External Files

20

Document Modes

20

The <noscript> Element

22

Summary 22

CHAPTER 3: LANGUAGE BASICS 25

Syntax 25

Case-sensitivity 25Identifi ers 26

Comments 26

Strict Mode 27

Statements 27

Keywords and Reserved Words

28

Variables 29

The Undefi ned Type 32

The Null Type 33

The Boolean Type 34

The Number Type 35

The String Type 41

The Object Type 44

Operators 45

Unary Operators 46

Bitwise Operators 49

Boolean Operators 56

Multiplicative Operators 59

Additive Operators 61

Relational Operators 63

Equality Operators 65

Conditional Operator 67

Assignment Operators 67

Comma Operator 68

Statements 69

The if Statement 69

The do-while Statement 70

The while Statement 70

The for Statement 71

The for-in Statement 72

Labeled Statements 73

The break and continue Statements 73

The with Statement 75

The switch Statement 76

Functions 78

Understanding Arguments 80

No Overloading 83

Summary 83

CHAPTER 4: VARIABLES, SCOPE, AND MEMORY 85

Primitive and Reference Values

85

Dynamic Properties 86

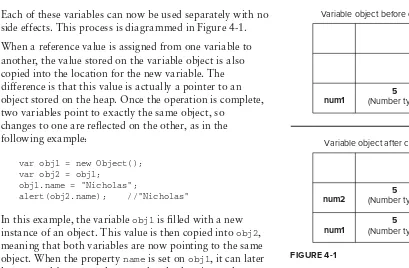

Copying Values 86

Argument Passing 88

Determining Type 89

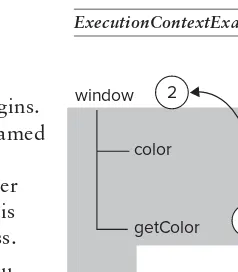

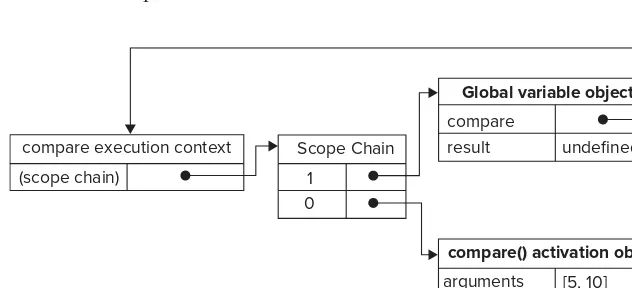

Execution Context and Scope

90

Scope Chain Augmentation 92

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 5: REFERENCE TYPES 103

The Object Type

104

Function Declarations versus Function Expressions 138

Functions as Values 139

Function Internals 141

Function Properties and Methods 143

CHAPTER 6: OBJECT-ORIENTED PROGRAMMING 173

Understanding Objects

173

Types of Properties 174

Defi ning Multiple Properties 178

Reading Property Attributes 179

Object Creation

180

The Factory Pattern 180

The Constructor Pattern 181

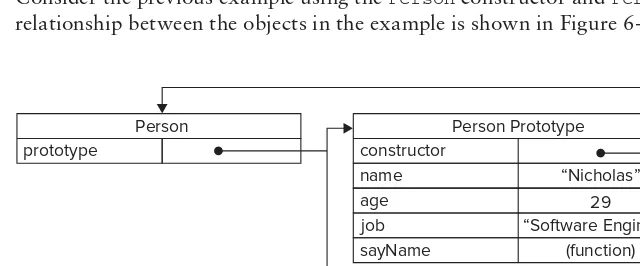

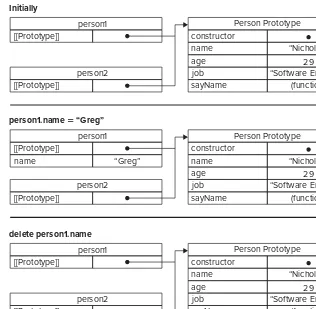

The Prototype Pattern 184

Combination Constructor/Prototype Pattern 197

Dynamic Prototype Pattern 198

Parasitic Constructor Pattern 199

Durable Constructor Pattern 200

Inheritance 201

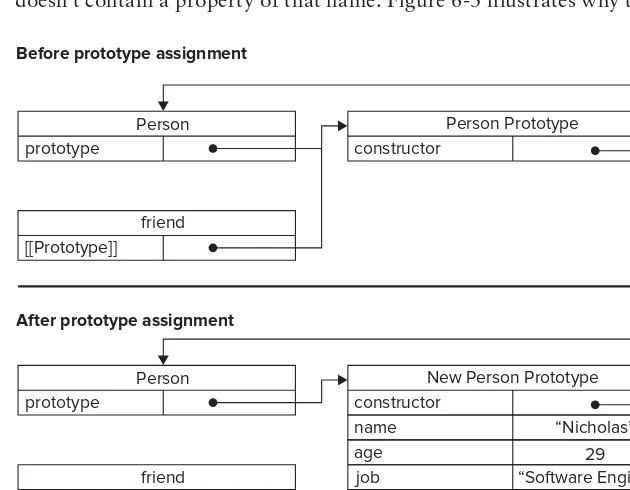

Prototype Chaining 202

Constructor Stealing 207

Combination Inheritance 209

Prototypal Inheritance 210

Parasitic Inheritance 211

Parasitic Combination Inheritance 212

Summary 215

CHAPTER 7: FUNCTION EXPRESSIONS 217

Recursion 220

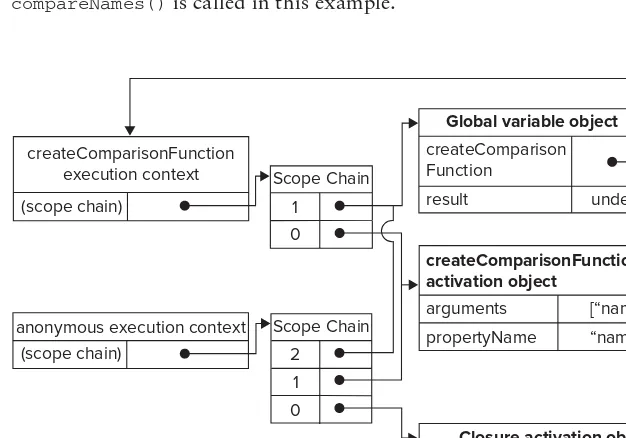

Closures 221

Closures and Variables 224

The this Object 225

Memory Leaks 227

Mimicking Block Scope

228

Private Variables

231

Static Private Variables 232

The Module Pattern 234

The Module-Augmentation Pattern 236

Summary 237

CHAPTER 8: THE BROWSER OBJECT MODEL 239

The window Object

239

The Global Scope 240

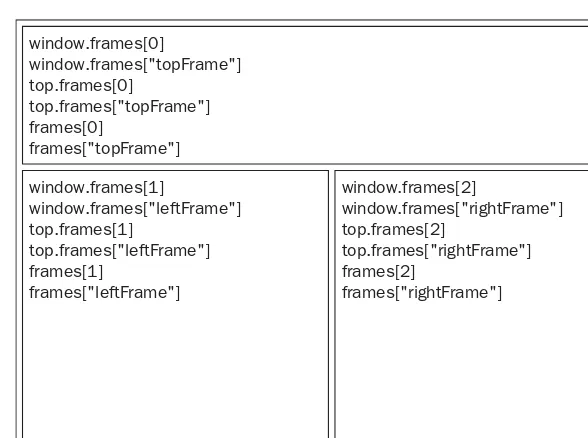

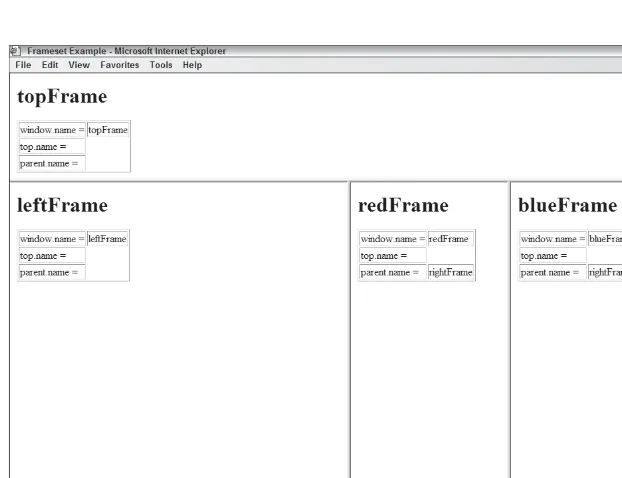

Window Relationships and Frames 241

CONTENTS

Window Size 245

Navigating and Opening Windows 247

Intervals and Timeouts 251

System Dialogs 253

The location Object

255

Query String Arguments 256

Manipulating the Location 257

The Navigator Object

259

Detecting Plug-ins 262

Registering Handlers 264

The screen Object

265

The history Object

267

Summary 268

CHAPTER 9: CLIENT DETECTION 271

Capability Detection

271

Safer Capability Detection 273

Capability Detection Is Not Browser Detection 274

Quirks Detection

275

User-Agent Detection

276

History 277

Working with User-Agent Detection 286

The Complete Script 303

Usage 306

Summary 306

CHAPTER 10: THE DOCUMENT OBJECT MODEL 309

Hierarchy of Nodes

310

The Node Type 310

The Document Type 316

The Element Type 326

The Text Type 337

The Comment Type 341

The CDATASection Type 342

The DocumentType Type 343

The DocumentFragment Type 344

The Attr Type 345

Working with the DOM

346

Dynamic Scripts 346

Manipulating Tables 350

Using NodeLists 353

Summary 354

CHAPTER 11: DOM EXTENSIONS 357

Selectors API

357

The querySelector() Method 358

The querySelectorAll() Method 358

The matchesSelector() Method 359

Element Traversal

360

HTML5 361

Class-Related Additions 361

Focus Management 364

Changes to HTMLDocument 364

Character Set Properties 366

Custom Data Attributes 366

Markup Insertion 367

The scrollIntoView() Method 372

Proprietary Extensions

372

Document Mode 373

The children Property 374

The contains() Method 374

Markup Insertion 376

Scrolling 379

Summary 379

CHAPTER 12: DOM LEVELS 2 AND 3 381

DOM Changes

382

XML Namespaces 382

Other Changes 386

Styles 390

Accessing Element Styles 391

Working with Style Sheets 396

Element Dimensions 401

Traversals 408

NodeIterator 410 TreeWalker 413Ranges 415

Ranges in the DOM 415

Ranges in Internet Explorer 8 and Earlier 424

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 13: EVENTS 431

Event Flow

432

Event Bubbling 432

Event Capturing 433

DOM Event Flow 433

Event Handlers

434

HTML Event Handlers 434

DOM Level 0 Event Handlers 437

DOM Level 2 Event Handlers 438

Internet Explorer Event Handlers 439

Cross-Browser Event Handlers 441

The Event Object

442

The DOM Event Object 442

The Internet Explorer Event Object 447

Cross-Browser Event Object 449

Event Types

451

UI Events 452

Focus Events 458

Mouse and Wheel Events 459

Keyboard and Text Events 471

Composition Events 478

Mutation Events 479

HTML5 Events 482

Device Events 490

Touch and Gesture Events 494

Memory and Performance

498

Event Delegation 498

Removing Event Handlers 500

Simulating Events

502

DOM Event Simulation 502

Internet Explorer Event Simulation 508

Summary 509

CHAPTER 14: SCRIPTING FORMS 511

Form Basics

511

Submitting Forms 512

Resetting Forms 513

Form Fields 514

Scripting Text Boxes

520

Input Filtering 524

Automatic Tab Forward 528

HTML5 Constraint Validation API 530

Scripting Select Boxes

534

Options Selection 536

Adding Options 537

Removing Options 538

Moving and Reordering Options 539

Form Serialization

540

Rich Text Editing

542

Using contenteditable 543

Interacting with Rich Text 543

Rich Text Selections 547

Rich Text in Forms 549

Summary 549

CHAPTER 15: GRAPHICS WITH CANVAS 551

Basic Usage

551

The 2D Context

553

Fills and Strokes 553

Drawing Rectangles 553

Drawing Paths 556

Drawing Text 557

Transformations 559

Drawing Images 563

Shadows 564 Gradients 565 Patterns 567

Working with Image Data 567

Compositing 569

WebGL 571

Typed Arrays 571

The WebGL Context 576

Support 588

Summary 588

CHAPTER 16: HTML5 SCRIPTING 591

Cross-Document Messaging

591

Native Drag and Drop

593

CONTENTS

Custom Drop Targets 594

The dataTransfer Object 595

DropEff ect and eff ectAllowed 596

Draggability 597

Additional Members 598

Media Elements

598

Properties 599 Events 601

Custom Media Players 602

Codec Support Detection 603

The Audio Type 604

History State Management

605

Summary 606

CHAPTER 17: ERROR HANDLING AND DEBUGGING 607

Browser Error Reporting

607

Internet Explorer 608

Firefox 609 Safari 610 Opera 612 Chrome 613

Error Handling

614

The try-catch Statement 615

Throwing Errors 619

The error Event 622

Error-handling Strategies 623

Identify Where Errors Might Occur 623

Distinguishing between Fatal and Nonfatal Errors 628

Log Errors to the Server 629

Debugging Techniques

630

Logging Messages to a Console 631

Logging Messages to the Page 633

Throwing Errors 634

Common Internet Explorer Errors

635

Operation Aborted 635

Invalid Character 637

Member Not Found 637

Unknown Runtime Error 638

Syntax Error 638

The System Cannot Locate the Resource Specifi ed 639

CHAPTER 18: XML IN JAVASCRIPT 641

XML DOM Support in Browsers

641

DOM Level 2 Core 641

The DOMParser Type 642

The XMLSerializer Type 644

XML in Internet Explorer 8 and Earlier 644

Cross-Browser XML Processing 649

XPath Support in Browsers

651

DOM Level 3 XPath 651

XPath in Internet Explorer 656

Cross-Browser XPath 657

XSLT Support in Browsers

660

XSLT in Internet Explorer 660

The XSLTProcessor Type 665

Cross-Browser XSLT 667

Summary 668

CHAPTER 19: ECMASCRIPT FOR XML 671

E4X Types

671

The XML Type 672

The XMLList Type 673

The Namespace Type 674

The QName Type 675

General Usage

676

Accessing Attributes 678

Other Node Types 679

Querying 681

XML Construction and Manipulation 682

Parsing and Serialization Options 685

Namespaces 686

Other Changes

688

Enabling Full E4X

689

Summary 689

CHAPTER 20: JSON 691

Syntax 691

Simple Values 692

Objects 692 Arrays 693

CONTENTS

The JSON Object 695

Serialization Options 696

Parsing Options 699

Summary 700

CHAPTER 21: AJAX AND COMET 701

The XMLHttpRequest Object

702

XHR Usage 703

HTTP Headers 706

GET Requests 707

POST Requests 708

XMLHttpRequest Level 2

710

The FormData Type 710

Timeouts 711

The overrideMimeType() Method 711

Progress Events

712

The load Event 712

The progress Event 713

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing

714

CORS in Internet Explorer 714

CORS in Other Browsers 716

Prefl ighted Requests 717

Credentialed Requests 718

Cross-Browser CORS 718

Alternate Cross-Domain Techniques

719

Image Pings 719

Comet 721

Server-Sent Events 723

Web Sockets 725

SSE versus Web Sockets 727

Security 728

Summary 729

CHAPTER 22: ADVANCED TECHNIQUES 731

Advanced Functions

731

Safe Type Detection 731

Scope-Safe Constructors 733

Lazy Loading Functions 736

Function Binding 738

Tamper-Proof Objects

743

Nonextensible Objects 744

Sealed Objects 744

Frozen Objects 745

Advanced Timers

746

Repeating Timers 748

Yielding Processes 750

Function Throttling 752

Custom Events

755

Drag and Drop

758

Fixing Drag Functionality 760

Adding Custom Events 762

Summary 764

CHAPTER 23: OFFLINE APPLICATIONS AND CLIENT-SIDE

STORAGE 765

Offl

ine Detection

765

Application Cache

766

Data Storage

768

Cookies 768

Internet Explorer User Data 778

Web Storage 780

IndexedDB 786

Summary 799

CHAPTER 24: BEST PRACTICES 801

Maintainability 801

What Is Maintainable Code? 802

Code Conventions 802

Loose Coupling 805

Programming Practices 809

Performance 814

Be Scope-Aware 814

Choose the Right Approach 816

Minimize Statement Count 821

Optimize DOM Interactions 824

Deployment 827

Build Process 827

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 25: EMERGING APIS 835

RequestAnimationFrame() 835

Early Animation Loops 836

Problems with Intervals 836

mozRequestAnimationFrame 837 webkitRequestAnimationFrame and msRequestAnimationFrame 838

Page Visibility API

839

Geolocation API

841

File API

843

The FileReader Type 844

Partial Reads 846

Object URLs 847

Drag-and-Drop File Reading 848

File Upload with XHR 849

Web Timing

851

Web Workers

852

Using a Worker 852

Worker Global Scope 853

Including Other Scripts 855

The Future of Web Workers 855

Summary 856

APPENDIX A: ECMASCRIPT HARMONY 857

General Changes

857

Constants 858

Block-Level and Other Scopes 858

Functions 859

Rest and Spread Arguments 859

Default Argument Values 860

Generators 861

Arrays and Other Structures

861

Iterators 862

Array Comprehensions 863

Destructuring Assignments 864

New Object Types

865

Proxy Objects 865

Proxy Functions 868

Map and Set 868

ArrayType 870

Classes 871

Private Members 872

Getters/Setters 872 Inheritance 873

Modules 874

External Modules 875

APPENDIX B: STRICT MODE 877

Opting-in 877

Variables 878

Objects 878

Functions 879

eval() 880

eval and arguments

881

Coercion of this

882

Other Changes

882

APPENDIX C: JAVASCRIPT LIBRARIES 885

General Libraries

885

Yahoo! User Interface Library (YUI) 885

Prototype 886

The Dojo Toolkit 886

MooTools 886 jQuery 886 MochiKit 886 Underscore.js 887

Internet Applications

887

Backbone.js 887 Rico 887 qooxdoo 887

Animation and Eff ects

888

script.aculo.us 888 moo.fx 888 Lightbox 888

Cryptography 888

JavaScript MD5 889

CONTENTS

APPENDIX D: JAVASCRIPT TOOLS 891

Validators 891

JSLint 891 JSHint 892JavaScript Lint 892

Minifi ers

892

JSMin 892

Dojo ShrinkSafe 892

YUI Compressor 893

Unit Testing

893

JsUnit 893

YUI Test 893

Dojo Object Harness (DOH) 894

qUnit 894

Documentation Generators

894

JsDoc Toolkit 894

YUI Doc 894

AjaxDoc 895

Secure Execution Environments

895

ADsafe 895 Caja 895

FOREWORD

I look back at my career (now 20+ years), and in between coming to the realization that my gray hairs have really sprouted out, I refl ect on the technologies and people that have dramatically affected my professional life and decisions. If I had to choose one technology, though, that has had the single biggest positive infl uence on me, it would be JavaScript. Mind you, I wasn’t always a JavaScript believer. Like many, I looked at it as a play language relegated to doing rotating banners and sprinkling some interesting effects on pages. I was a server-side developer, and we didn’t play with toy languages, damn it! But then something happened: Ajax.

I’ll never forget hearing the buzzword Ajax all over the place and thinking that it was some very cool, new, and innovative technology. I had to check it out, and as I read about it, I was fl oored when I realized that the toy language I had so readily dismissed was now the technology that was on the lips of every professional web developer. And suddenly, my perception changed. As I continued to explore past what Ajax was, I realized that JavaScript was incredibly powerful, and I wanted in on all the goodness it had to offer. So I embraced it wholeheartedly, working to understand the language, joining the jQuery project team, and focusing on client-side development. Life was good.

The deeper I became involved in JavaScript, the more developers I met, some whom to this day I still see as rock stars and mentors. Nicholas Zakas is one of those developers. I remember reading the second edition of this very book and feeling like, despite all of my years of tinkering, I had learned so much from it. And the book felt genuine and thoughtful, as if Nicholas understood that his audience’s experience level would vary and that he needed to manage the tone accordingly. That really stood out in terms of technical books. Most authors try to go into the deep-dive technobabble to impress. This was different, and it immediately became my go-to book and the one I recommended to any developer who wanted to get a solid understanding of JavaScript. I wanted everyone to feel the same way I felt and realize how valuable a resource it is.

And then, at a jQuery conference, I had the amazing fortune of actually meeting Nicholas in person. Here was one of top JavaScript developers in the world working on one of the most important web properties in the world (Yahoo!), and he was one of the nicest people I had ever met. I admit; I was a bit starstruck when I met him. And the great thing was that he was just this incredibly down-to-earth person who just wanted to help developers be great. So not only did his book change the way I thought about JavaScript, but Nicholas himself was someone that I wanted to continue to work with and get to know.

The smooth and thoughtful transition from introductory topics such as expressions and variable declarations to advanced topics such as closures and object-oriented development is what sets it apart from other books that either are too introductory or expect that you’re already building missile guidance systems with JavaScript. It’s the “everyman’s” book that will help you write code that you’ll be proud of and build web site that will excite and delight.

INTRODUCTION

SOME CLAIM THAT JAVASCRIPT is now the most popular programming language in the world, running any number of complex web applications that the world relies on to do business, make purchases, manage processes, and more.

JavaScript is very loosely based on Java, an object-oriented programming language popularized for use on the Web by way of embedded applets. Although JavaScript has a similar syntax and programming methodology, it is not a “light” version of Java. Instead, JavaScript is its own dynamic language, fi nding its home in web browsers around the world and enabling enhanced user interaction on web sites and web applications alike.

In this book, JavaScript is covered from its very beginning in the earliest Netscape browsers to the present-day incarnations fl ush with support for the DOM and Ajax. You learn how to extend the language to suit specifi c needs and how to create seamless client-server communication without intermediaries such as Java or hidden frames. In short, you learn how to apply JavaScript solutions to business problems faced by web developers everywhere.

WHO THIS BOOK IS FOR

This book is aimed at three groups of readers:

Experienced developers familiar with object-oriented programming who are looking to learn JavaScript as it relates to traditional OO languages such as Java and C++.

Web application developers attempting to enhance the usability of their web sites and web applications.

Novice JavaScript developers aiming to better understand the language.

In addition, familiarity with the following related technologies is a strong indicator that this book is for you:

Java PHP ASP.NET HTML

CSS XML

This book is not aimed at beginners lacking a basic computer science background or those looking to add some simple user interactions to web sites. These readers should instead refer to Wrox’s

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

WHAT THIS BOOK COVERS

Professional JavaScript for Web Developers, 3rd Edition, provides a developer-level introduction, along with the more advanced and useful features of JavaScript.

Starting at the beginning, the book explores how JavaScript originated and evolved into what it is today. A detailed discussion of the components that make up a JavaScript implementation follows, with specifi c focus on standards such as ECMAScript and the Document Object Model (DOM). The differences in JavaScript implementations used in different popular web browsers are also discussed.

Building on that base, the book moves on to cover basic concepts of JavaScript including its version of object-oriented programming, inheritance, and its use in HTML. An in-depth examination of events and event handling is followed by an exploration of browser detection techniques. The book then explores new APIs such as HTML5, the Selectors API, and the File API.

The last part of the book is focused on advanced topics including performance/memory optimization, best practices, and a look at where JavaScript is going in the future.

HOW THIS BOOK IS STRUCTURED

This book comprises the following chapters:

1.

What Is JavaScript? — Explains the origins of JavaScript: where it came from, how it evolved, and what it is today. Concepts introduced include the relationship between JavaScript and ECMAScript, the Document Object Model (DOM), and the Browser Object Model (BOM). A discussion of the relevant standards from the European Computer Manufacturer’s Association (ECMA) and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is also included.2.

JavaScript in HTML — Examines how JavaScript is used in conjunction with HTML to create dynamic web pages. Introduces the various ways of embedding JavaScript into a page including a discussion surrounding the JavaScript content-type and its relationship to the <script> element.3.

Language Basics — Introduces basic language concepts including syntax and fl ow control statements. Explains the syntactic similarities of JavaScript and other C-based languages and points out the differences. Type coercion is introduced as it relates to built-in operators.4.

Variables, Scope, and Memory — Explores how variables are handled in JavaScriptgiven their loosely typed nature. A discussion about the differences between primitive and reference values is included, as is information about execution context as it relates to variables. Also, a discussion about garbage collection in JavaScript explains how memory is reclaimed when variables go out of scope.

INTRODUCTION

6.

Object-Oriented Programming — Explains how to use object-oriented programming in JavaScript. Since JavaScript has no concept of classes, several popular techniques are explored for object creation and inheritance. Also covered in this chapter is the concept of function prototypes and how that relates to an overall OO approach.7.

Function Expressions — Explores one of the most powerful aspects of JavaScript: function expressions. Topics include closures, how the this object works, the module pattern, and creating private object members.8.

The Browser Object Model — Introduces the Browser Object Model (BOM), which is responsible for objects allowing interaction with the browser itself. Each of the BOM objects is covered, including window, document, location, navigator, and screen.9.

Client Detection — Explains various approaches to detecting the client machine and its capabilities. Different techniques include capability detection and user-agent string detection. Each approach is discussed for pros and cons, as well as situational appropriateness.10.

The Document Object Model — Introduces the Document Object Model (DOM) objects available in JavaScript as defi ned in DOM Level 1. A brief introduction to XML and its relationship to the DOM gives way to an in-depth exploration of the entire DOM and how it allows developers to manipulate a page.11.

DOM Extensions — Explains how other APIs, as well as the browsers themselves, extend the DOM with more functionality. Topics include the Selectors API, the Element Traversal API, and HTML5 extensions.12.

DOM Levels 2 and 3 — Builds on the previous two chapters, explaining how DOM Levels 2 and 3 augmented the DOM with additional properties, methods, and objects. Compatibility issues between Internet Explorer and other browsers are discussed.13.

Events — Explains the nature of events in JavaScript, where they originated, legacy support, and how the DOM redefi ned how events should work. A variety of devices are covered including the Wii and iPhone.14.

Scripting Forms — Looks at using JavaScript to enhance form interactions and work around browser limitations. Discussion focuses on individual form elements such as text boxes and select boxes and on data validation and manipulation.15.

Graphics with Canvas — Discusses the <canvas> tag and how to use it to create on-the-fl y graphics. Both the 2D context and the WebGL (3D) context are covered, giving you a good starting point for creating animations and games.16.

HTML5 Scripting — Introduces JavaScript API changes as defi ned in HTML5. Topics include cross-document messaging, the Drag-and-Drop API scripting <audio> and <video> elements, as well as history state management.18.

XML in JavaScript — Presents the features of JavaScript used to read and manipulate eXtensible Markup Language (XML) data. Explains the differences in support and objects in various web browsers and offers suggestions for easier cross-browser coding. This chapter also covers the use of eXtensible Stylesheet Language Transformations (XSLT) to transform XML data on the client.19.

ECMAScript for XML — Discusses the ECMAScript for XML (E4X) extension to JavaScript, which is designed to simplify working with XML. Explains the advantages of E4X over using the DOM for XML manipulation.20.

JSON — Introduces the JSON data format as an alternative to XML. Browser-native JSON parsing and serialization are discussed as are security considerations when using JSON.21.

Ajax and Comet — Looks at common Ajax techniques including the use of theXMLHttpRequest object and Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) for cross-domain Ajax. Explains the differences in browser implementations and support and provides recommendations for usage.

22.

Advanced Techniques — Dives into some of the more complex JavaScript patterns, including function currying, partial function application, and dynamic functions. Also covers creating a custom event framework to enable simple event support for custom objects and creating tamper-proof objects using ECMAScript 5.23.

Offl ine Applications and Client-Side Storage — Discusses how to detect when an application is offl ine and provides various techniques for storing data on the client machine. Begins with a discussion of the most commonly supported feature, cookies, and then discusses newer functionality such as Web Storage and IndexedDB.24.

Best Practices — Explores approaches to working with JavaScript in an enterprise environment. Techniques for better maintainability are discussed, including coding techniques, formatting, and general programming practices. Execution performance is discussed, and several techniques for speed optimization are introduced. Last, deployment issues are discussed, including how to create a build process.25.

Emerging APIs — Introduces APIs being created to augment JavaScript in the browser. Even though these APIs aren’t yet complete or fully implemented, they are on the horizon, and browsers have already begun partially implementing their features. Includes discussion of Web Timing, geolocation, and the File API.WHAT YOU NEED TO USE THIS BOOK

To run the samples in the book, you need the following:

Windows XP, Windows 7, or Mac OS X

Internet Explorer 6 or higher, Firefox 2 or higher, Opera 9 or higher, Chrome, or Safari 2 or higher

The complete source code for the samples is available for download from the web site at www.wrox.com. ➤

INTRODUCTION

CONVENTIONS

To help you get the most from the text and keep track of what’s happening, we’ve used a number of conventions throughout the book.

Boxes with a warning icon like this one hold important, not-to-be forgotten information that is directly relevant to the surrounding text.

The pencil icon indicates notes, tips, hints, tricks, and asides to the current discussion.

As for styles in the text:

We highlight new terms and important words when we introduce them. We show keyboard strokes like this: Ctrl+A.

We show fi le names, URLs, and code within the text like so: persistence.properties.

We present code in two different ways:

We use a monofont type with no highlighting for most code examples.

We use bold to emphasize code that’s particularly important in the present context.

SOURCE CODE

As you work through the examples in this book, you may choose either to type in all the code manually or to use the source code fi les that accompany the book. All the source code used in this book is available for download at www.wrox.com. When at the site, simply locate the book’s title (use the Search box or one of the title lists) and click the Download Code link on the book’s detail page to obtain all the source code for the book. Code that is included on the web site is highlighted by the following icon:

Listings include the fi le name in the title. If it is just a code snippet, you’ll fi nd the fi le name in a code note such as this:

Code snippet fi le name ➤

➤

➤

Once you download the code, just decompress it with your favorite compression tool. Alternately, you can go to the main Wrox code download page at www.wrox.com/dynamic/books/download .aspx to see the code available for this book and all other Wrox books.

ERRATA

We make every effort to ensure that there are no errors in the text or in the code. However, no one is perfect, and mistakes do occur. If you fi nd an error in one of our books, like a spelling mistake or faulty piece of code, we would be very grateful for your feedback. By sending in errata you may save another reader hours of frustration and at the same time you will be helping us provide even higher quality information.

To fi nd the errata page for this book, go to www.wrox.com and locate the title using the Search box or one of the title lists. Then, on the book details page, click the Book Errata link. On this page you can view all errata that have been submitted for this book and posted by Wrox editors. A complete book list including links to each book’s errata is also available at www.wrox.com/misc-pages/ booklist.shtml.

If you don’t spot “your” error on the Book Errata page, go to www.wrox.com/contact/

techsupport.shtml and complete the form there to send us the error you have found. We’ll check the information and, if appropriate, post a message to the book’s errata page and fi x the problem in subsequent editions of the book.

P2P.WROX.COM

For author and peer discussion, join the P2P forums at p2p.wrox.com. The forums are a Web-based system for you to post messages relating to Wrox books and related technologies and interact with other readers and technology users. The forums offer a subscription feature to e-mail you topics of interest of your choosing when new posts are made to the forums. Wrox authors, editors, other industry experts, and your fellow readers are present on these forums.

At p2p.wrox.com you will fi nd a number of different forums that will help you not only as you read this book but also as you develop your own applications. To join the forums, just follow these steps:

1.

Go to p2p.wrox.com and click the Register link.2.

Read the terms of use and click Agree.INTRODUCTION

3.

Complete the required information to join, as well as any optional information you wish to provide, and click Submit.4.

You will receive an e-mail with information describing how to verify your account and complete the joining process.You can read messages in the forums without joining P2P, but in order to post your own messages, you must join.

Once you join, you can post new messages and respond to messages other users post. You can read messages at any time on the Web. If you would like to have new messages from a particular forum e-mailed to you, click the Subscribe to this Forum icon by the forum name in the forum listing.

What Is JavaScript?

WHAT’S IN THIS CHAPTER?

Review of JavaScript history

What JavaScript is

How JavaScript and ECMAScript are related

The diff erent versions of JavaScript

When JavaScript fi rst appeared in 1995, its main purpose was to handle some of the input validation that had previously been left to server-side languages such as Perl. Prior to that time, a round-trip to the server was needed to determine if a required fi eld had been left blank or an entered value was invalid. Netscape Navigator sought to change that with the introduction of JavaScript. The capability to handle some basic validation on the client was an exciting new feature at a time when use of telephone modems was widespread. The associated slow speeds turned every trip to the server into an exercise in patience.

Since that time, JavaScript has grown into an important feature of every major web browser on the market. No longer bound to simple data validation, JavaScript now interacts with nearly all aspects of the browser window and its contents. JavaScript is recognized as a full programming language, capable of complex calculations and interactions, including closures, anonymous (lambda) functions, and even metaprogramming. JavaScript has become such an important part of the Web that even alternative browsers, including those on mobile phones and those designed for users with disabilities, support it. Even Microsoft, with its own client-side scripting language called VBScript, ended up including its own JavaScript implementation in Internet Explorer from its earliest version.

The rise of JavaScript from a simple input validator to a powerful programming language could not have been predicted. JavaScript is at once a very simple and very complicated language that takes minutes to learn but years to master. To begin down the path to using JavaScript’s full potential, it is important to understand its nature, history, and limitations.

A SHORT HISTORY

As the Web gained popularity, a gradual demand for client-side scripting languages developed. At the time, most Internet users were connecting over a 28.8 kbps modem even though web pages were growing in size and complexity. Adding to users’ pain was the large number of round-trips to the server required for simple form validation. Imagine fi lling out a form, clicking the Submit button, waiting 30 seconds for processing, and then being met with a message indicating that you forgot to complete a required fi eld. Netscape, at that time on the cutting edge of technological innovation, began seriously considering the development of a client-side scripting language to handle simple processing.

Brendan Eich, who worked for Netscape at the time, began developing a scripting language called Mocha, and later LiveScript, for the release of Netscape Navigator 2 in 1995, with the intention of using it both in the browser and on the server (where it was to be called LiveWire). Netscape entered into a development alliance with Sun Microsystems to complete the implementation of LiveScript in time for release. Just before Netscape Navigator 2 was offi cially released, Netscape changed LiveScript’s name to JavaScript to capitalize on the buzz that Java was receiving from the press.

Because JavaScript 1.0 was such a hit, Netscape released version 1.1 in Netscape Navigator 3. The popularity of the fl edgling Web was reaching new heights, and Netscape had positioned itself to be the leading company in the market. At this time, Microsoft decided to put more resources into a competing browser named Internet Explorer. Shortly after Netscape Navigator 3 was released, Microsoft introduced Internet Explorer 3 with a JavaScript implementation called JScript (so called to avoid any possible licensing issues with Netscape). This major step for Microsoft into the realm of web browsers in August 1996 is now a date that lives in infamy for Netscape, but it also represented a major step forward in the development of JavaScript as a language.

Microsoft’s implementation of JavaScript meant that there were two different JavaScript versions fl oating around: JavaScript in Netscape Navigator and JScript in Internet Explorer. Unlike C and many other programming languages, JavaScript had no standards governing its syntax or features, and the three different versions only highlighted this problem. With industry fears mounting, it was decided that the language must be standardized.

In 1997, JavaScript 1.1 was submitted to the European Computer Manufacturers Association (Ecma) as a proposal. Technical Committee #39 (TC39) was assigned to “standardize the syntax and semantics of a general purpose, cross-platform, vendor-neutral scripting language” (www.ecma-international.org/memento/TC39.htm). Made up of programmers from Netscape, Sun, Microsoft, Borland, NOMBAS, and other companies with interest in the future of scripting, TC39 met for months to hammer out ECMA-262, a standard defi ning a new scripting language named ECMAScript (often pronounced as “ek-ma-script”).

The following year, the International Organization for Standardization and International

JavaScript Implementations

❘

3JAVASCRIPT IMPLEMENTATIONS

Though JavaScript and ECMAScript are often used synonymously, JavaScript is much more than just what is defi ned in ECMA-262. Indeed, a complete JavaScript implementation is made up of the following three distinct parts (see Figure 1-1):

The Core (ECMAScript)

The Document Object Model (DOM)

The Browser Object Model (BOM)

ECMAScript

ECMAScript, the language defi ned in ECMA-262, isn’t tied to web browsers. In fact, the language has no methods for input or output whatsoever. ECMA-262 defi nes this language as a base upon which more-robust scripting languages may be built. Web browsers are just one host environment in which an ECMAScript implementation may exist. A host environment provides the base implementation of ECMAScript and implementation extensions designed to interface with the environment itself. Extensions, such as the Document Object Model (DOM), use ECMAScript’s core types and syntax to provide additional functionality that’s more specifi c to the environment. Other host environments include NodeJS, a server-side JavaScript platform, and Adobe Flash.

What exactly does ECMA-262 specify if it doesn’t reference web browsers? On a very basic level, it describes the following parts of the language:

Syntax Types Statements

Keywords Reserved words Operators Objects

ECMAScript is simply a description of a language implementing all of the facets described in the specifi cation. JavaScript implements ECMAScript, but so does Adobe ActionScript.

ECMAScript Editions

The different versions of ECMAScript are defi ned as editions (referring to the edition of ECMA-262 in which that particular implementation is described). The most recent edition of ECMA-262 is edition 5, released in 2009. The fi rst edition of ECMA-262 was essentially the

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

➤

FIGURE 1-1

JavaScript

same as Netscape’s JavaScript 1.1 but with all references to browser-specifi c code removed and a few minor changes: ECMA-262 required support for the Unicode standard (to support multiple languages) and that objects be platform-independent (Netscape JavaScript 1.1 actually had different implementations of objects, such as the Date object, depending on the platform). This was a major reason why JavaScript 1.1 and 1.2 did not conform to the fi rst edition of ECMA-262.

The second edition of ECMA-262 was largely editorial. The standard was updated to get into strict agreement with ISO/IEC-16262 and didn’t feature any additions, changes, or omissions. ECMAScript implementations typically don’t use the second edition as a measure of conformance.

The third edition of ECMA-262 was the fi rst real update to the standard. It provided updates to string handling, the defi nition of errors, and numeric outputs. It also added support for regular expressions, new control statements, try-catch exception handling, and small changes to better prepare the standard for internationalization. To many, this marked the arrival of ECMAScript as a true programming language.

The fourth edition of ECMA-262 was a complete overhaul of the language. In response to the popularity of JavaScript on the Web, developers began revising ECMAScript to meet the growing demands of web development around the world. In response, Ecma TC39 reconvened to decide the future of the language. The resulting specifi cation defi ned an almost completely new language based on the third edition. The fourth edition includes strongly typed variables, new statements and data structures, true classes and classical inheritance, and new ways to interact with data.

As an alternate proposal, a specifi cation called “ECMAScript 3.1,” was developed as a smaller evolution of the language by a subcommittee of TC39, who believed that the fourth edition was too big of a jump for the language. The result was a smaller proposal with incremental changes to ECMAScript that could be implemented on top of existing JavaScript engines. Ultimately, the ES3.1 subcommittee won over support from TC39, and the fourth edition of ECMA-262 was abandoned before offi cially being published.

ECMAScript 3.1 became ECMA-262, fi fth edition, and was offi cially published on December 3, 2009. The fi fth edition sought to clarify perceived ambiguities of the third edition and introduce additional functionality. The new functionality includes a native JSON object for parsing and serializing JSON data, methods for inheritance and advanced property defi nition, and the inclusion of a new strict mode that slightly augments how ECMAScript engines interpret and execute code.

What Does ECMAScript Conformance Mean?

ECMA-262 lays out the defi nition of ECMAScript conformance. To be considered an implementation of ECMAScript, an implementation must do the following:

Support all “types, values, objects, properties, functions, and program syntax and semantics” (ECMA-262, p. 1) as they are described in ECMA-262.

Support the Unicode character standard. ➤

JavaScript Implementations

❘

5Additionally, a conforming implementation may do the following:

Add “additional types, values, objects, properties, and functions” that are not specifi ed in ECMA-262. ECMA-262 describes these additions as primarily new objects or new properties of objects not given in the specifi cation.

Support “program and regular expression syntax” that is not defi ned in ECMA-262 (meaning that the built-in regular-expression support is allowed to be altered and extended).

These criteria give implementation developers a great amount of power and fl exibility for developing new languages based on ECMAScript, which partly accounts for its popularity.

ECMAScript Support in Web Browsers

Netscape Navigator 3 shipped with JavaScript 1.1 in 1996. That same JavaScript 1.1 specifi cation was then submitted to Ecma as a proposal for the new standard, ECMA-262. With JavaScript’s explosive popularity, Netscape was very happy to start developing version 1.2. There was, however, one problem: Ecma hadn’t yet accepted Netscape’s proposal.

A little after Netscape Navigator 3 was released, Microsoft introduced Internet Explorer 3. This version of IE shipped with JScript 1.0, which was supposed to be equivalent to JavaScript 1.1. However, because of undocumented and improperly replicated features, JScript 1.0 fell far short of JavaScript 1.1.

Netscape Navigator 4 was shipped in 1997 with JavaScript 1.2 before the fi rst edition of ECMA-262 was accepted and standardized later that year. As a result, JavaScript 1.2 is not compliant with the fi rst edition of ECMAScript even though ECMAScript was supposed to be based on JavaScript 1.1.

The next update to JScript occurred in Internet Explorer 4 with JScript version 3.0 (version 2.0 was released in Microsoft Internet Information Server version 3.0 but was never included in a browser). Microsoft put out a press release touting JScript 3.0 as the fi rst truly Ecma-compliant scripting language in the world. At that time, ECMA-262 hadn’t yet been fi nalized, so JScript 3.0 suffered the same fate as JavaScript 1.2: it did not comply with the fi nal ECMAScript standard.

Netscape opted to update its JavaScript implementation in Netscape Navigator 4.06 to JavaScript 1.3, which brought Netscape into full compliance with the fi rst edition of ECMA-262. Netscape added support for the Unicode standard and made all objects platform-independent while keeping the features that were introduced in JavaScript 1.2.

When Netscape released its source code to the public as the Mozilla project, it was anticipated that JavaScript 1.4 would be shipped with Netscape Navigator 5. However, a radical decision to completely redesign the Netscape code from the bottom up derailed that effort. JavaScript 1.4 was released only as a server-side language for Netscape Enterprise Server and never made it into a web browser.

By 2008, the fi ve major web browsers (Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari, Chrome, and Opera) all complied with the third edition of ECMA-262. Internet Explorer 8 was the fi rst to start implementing the fi fth edition of ECMA-262 specifi cation and delivered complete support in Internet Explorer 9. Firefox 4 soon followed suit. The following table lists ECMAScript support in

➤

BROWSER ECMASCRIPT COMPLIANCE Netscape Navigator 2 —

Netscape Navigator 3 —

Netscape Navigator 4–4.05 —

Netscape Navigator 4.06–4.79 Edition 1

Netscape 6+ (Mozilla 0.6.0+) Edition 3

Internet Explorer 3 —

Internet Explorer 4 —

Internet Explorer 5 Edition 1

Internet Explorer 5.5–7 Edition 3

Internet Explorer 8 Edition 5*

Internet Explorer 9+ Edition 5

Opera 6–7.1 Edition 2

Opera 7.2+ Edition 3

Safari 1–2.0.x Edition 3*

Safari 3.x Edition 3

Safari 4.x–5.x Edition 5*

Chrome 1+ Edition 3

Firefox 1–2 Edition 3

Firefox 3.0.x Edition 3

Firefox 3.5–3.6 Edition 5*

Firefox 4+ Edition 5

*Incomplete implementations

The Document Object Model (DOM)

JavaScript Implementations

❘

7<html> <head>

<title>Sample Page</title> </head>

<body>

<p>Hello World!</p> </body>

</html>

This code can be diagrammed into a hierarchy of nodes using the DOM (see Figure 1-2).

By creating a tree to represent a document, the DOM allows developers an unprecedented level of control over its content and structure. Nodes can be removed, added, replaced, and modifi ed easily by using the DOM API.

Why the DOM Is Necessary

With Internet Explorer 4 and Netscape Navigator 4 each

supporting different forms of Dynamic HTML (DHTML), developers for the fi rst time could alter the appearance and content of a web page without reloading it. This represented a tremendous step forward in web technology but also a huge problem. Netscape and Microsoft went separate ways in developing DHTML, thus ending the period when developers could write a single HTML page that could be accessed by any web browser.

It was decided that something had to be done to preserve the cross-platform nature of the Web. The fear was that if someone didn’t rein in Netscape and Microsoft, the Web would develop into two distinct factions that were exclusive to targeted browsers. It was then that the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the body charged with creating standards for web communication, began working on the DOM.

DOM Levels

DOM Level 1 became a W3C recommendation in October 1998. It consisted of two modules: the DOM Core, which provided a way to map the structure of an XML-based document to allow for easy access to and manipulation of any part of a document, and the DOM HTML, which extended the DOM Core by adding HTML-specifi c objects and methods.

Sample Page html

head

title

body

p

Hello World!

FIGURE 1-2

Note that the DOM is not JavaScript-specifi c and indeed has been implemented in numerous other languages. For web browsers, however, the DOM has been implemented using ECMAScript and now makes up a large part of the JavaScript language.

DOM Level 2 introduced the following new modules of the DOM to deal with new types of interfaces:

DOM Views — Describes interfaces to keep track of the various views of a document (the document before and after CSS styling, for example)

DOM Events — Describes interfaces for events and event handling

DOM Style — Describes interfaces to deal with CSS-based styling of elements

DOM Traversal and Range — Describes interfaces to traverse and manipulate a document tree

DOM Level 3 further extends the DOM with the introduction of methods to load and save

documents in a uniform way (contained in a new module called DOM Load and Save) and methods to validate a document (DOM Validation). In Level 3, the DOM Core is extended to support all of XML 1.0, including XML Infoset, XPath, and XML Base.

➤

➤

➤

➤

When reading about the DOM, you may come across references to DOM Level 0. Note that there is no standard called DOM Level 0; it is simply a reference point in the history of the DOM. DOM Level 0 is considered to be the original DHTML supported in Internet Explorer 4.0 and Netscape Navigator 4.0.

Other DOMs

Aside from the DOM Core and DOM HTML interfaces, several other languages have had their own DOM standards published. The languages in the following list are XML-based, and each DOM adds methods and interfaces unique to a particular language:

Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.0

Mathematical Markup Language (MathML) 1.0 Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language (SMIL)

Additionally, other languages have developed their own DOM implementations, such as Mozilla’s XML User Interface Language (XUL). However, only the languages in the preceding list are standard recommendations from W3C.

DOM Support in Web Browsers

The DOM had been a standard for some time before web browsers started implementing it. Internet Explorer made its fi rst attempt with version 5, but it didn’t have any realistic DOM support until version 5.5, when it implemented most of DOM Level 1. Internet Explorer didn’t introduce new DOM functionality in versions 6 and 7, though version 8 introduced some bug fi xes.

For Netscape, no DOM support existed until Netscape 6 (Mozilla 0.6.0) was introduced. After Netscape 7, Mozilla switched its development efforts to the Firefox browser. Firefox 3+ supports all of Level 1, nearly all of Level 2, and some parts of Level 3. (The goal of the Mozilla development team was to build a 100 percent standards-compliant browser, and their work paid off.)

➤

➤

JavaScript Implementations

❘

9DOM support became a huge priority for most browser vendors, and efforts have been ongoing to improve support with each release. The following table shows DOM support for popular browsers.

BROWSER DOM COMPLIANCE

Netscape Navigator 1.–4.x —

Netscape 6+ (Mozilla 0.6.0+) Level 1, Level 2 (almost all), Level 3 (partial)

Internet Explorer 2–4.x —

Internet Explorer 5 Level 1 (minimal)

Internet Explorer 5.5–8 Level 1 (almost all)

Internet Explorer 9+ Level 1, Level 2, Level 3

Opera 1–6 —

Opera 7–8.x Level 1 (almost all), Level 2 (partial)

Opera 9–9.9 Level 1, Level 2 (almost all), Level 3 (partial)

Opera 10+ Level 1, Level 2, Level 3 (partial)

Safari 1.0.x Level 1

Safari 2+ Level 1, Level 2 (partial)

Chrome 1+ Level 1, Level 2 (partial)

Firefox 1+ Level 1, Level 2 (almost all), Level 3 (partial)

The Browser Object Model (BOM)

The Internet Explorer 3 and Netscape Navigator 3 browsers featured a Browser Object Model (BOM) that allowed access and manipulation of the browser window. Using the BOM, developers can interact with the browser outside of the context of its displayed page. What made the BOM truly unique, and often problematic, was that it was the only part of a JavaScript implementation that had no related standard. This changed with the introduction of HTML5, which sought to codify much of the BOM as part of a formal specifi cation. Thanks to HTML5, a lot of the confusion surrounding the BOM has dissipated.

Primarily, the BOM deals with the browser window and frames, but generally any browser-specifi c extension to JavaScript is considered to be a part of the BOM. The following are some such extensions:

The capability to pop up new browser windows

The capability to move, resize, and close browser windows

The object, which provides detailed information about the browser ➤

The location object, which gives detailed information about the page loaded in the browser

The screen object, which gives detailed information about the user’s screen resolution

Support for cookies

Custom objects such as XMLHttpRequest and Internet Explorer’s ActiveXObject Because no standards existed for the BOM for a long time, each browser has its own implementation. There are some de facto standards, such as having a window object and a navigator object, but each browser defi nes its own properties and methods for these and other objects. With HTML5 now available, the implementation details of the BOM are expected to grow in a much more compatible way. A detailed discussion of the BOM is included in Chapter 8.

JAVASCRIPT VERSIONS

Mozilla, as a descendant from the original Netscape, is the only browser vendor that has continued the original JavaScript version-numbering sequence. When the Netscape source code was spun off into an open-source project (named the Mozilla Project), the last browser version of JavaScript was 1.3. (As mentioned previously, version 1.4 was implemented on the server exclusively.) As the Mozilla Foundation continued work on JavaScript, adding new features, keywords, and syntaxes, the JavaScript version number was incremented. The following table shows the JavaScript version progression in Netscape/Mozilla browsers.

BROWSER JAVASCRIPT VERSION

Netscape Navigator 2 1.0

Netscape Navigator 3 1.1

Netscape Navigator 4 1.2

Netscape Navigator 4.06 1.3

Netscape 6+ (Mozilla 0.6.0+) 1.5

Firefox 1 1.5

Firefox 1.5 1.6

Firefox 2 1.7

Firefox 3 1.8

Firefox 3.5 1.8.1

Firefox 3.6 1.8.2

➤

➤

➤

Summary

❘

11The numbering scheme was based on the idea that Firefox 4 would feature JavaScript 2.0, and each increment in the version number prior to that point indicates how close the JavaScript implementation is to the 2.0 proposal. Though this was the original plan, the evolution of JavaScript happened in such a way that this was no longer possible. There is currently no target implementation for JavaScript 2.0.

It’s important to note that only the Netscape/Mozilla browsers follow this versioning scheme. Internet Explorer, for example, has different version numbers for JScript. These JScript versions don’t correspond whatsoever to the JavaScript versions mentioned in the preceding table. Furthermore, most browsers talk about JavaScript support in relation to their level of ECMAScript compliance and DOM support.

SUMMARY

JavaScript is a scripting language designed to interact with web pages and is made up of the following three distinct parts:

ECMAScript, which is defi ned in ECMA-262 and provides the core functionality

The Document Object Model (DOM), which provides methods and interfaces for working with the content of a web page

The Browser Object Model (BOM), which provides methods and interfaces for interacting with the browser

There are varying levels of support for the three parts of JavaScript across the fi ve major web browsers (Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome, Safari, and Opera). Support for ECMAScript 3 is generally good across all browsers, and support for ECMAScript 5 is growing, whereas support for the DOM varies widely. The BOM, recently codifi ed in HTML5, can vary from browser to browser, though there are some commonalities that are assumed to be available.

➤

➤