A Decline in Executive Abilities beyond That Observed

in Healthy Volunteers

Robert Fucetola, Larry J. Seidman, William S. Kremen, Stephen V. Faraone,

Jill M. Goldstein, and Ming T. Tsuang

Background: Kraepelin originally conceptualized schizo-phrenia as a degenerative brain disorder. It remains unclear whether the illness is characterized by a static encephalopathy or a deterioration of brain function, or periods of each condition. Assessments of cognitive func-tion, as measured by neuropsychologic assessment, can provide additional insight into this question. Few studies of patients with schizophrenia have investigated the effect of aging on executive functions, in an extensive neuropsy-chologic battery across a wide age range, compared to healthy volunteers.

Methods: We examined the interaction of aging and neuropsychologic function in schizophrenia through a cross-sectional study in patients (n 5 87) and healthy control subjects (n594). Subjects were divided into three age groups (20 –35, 36 – 49, and 50 –75), and performance on an extensive neuropsychologic battery was evaluated. Results: Compared to control subjects, patients with schizophrenia demonstrated similar age-related declines across most neuropsychologic functions, with the excep-tion of abstracexcep-tion ability, in which significant evidence of a more accelerated decline was observed.

Conclusions: These results are consistent with previous reports indicating similar age effects on most aspects of cognition in patients with schizophrenia and healthy adults, but they support the hypothesis that a degenerative process may result in a more accelerated decline of some executive functions in older age in schizophrenia. Biol

Psychiatry 2000;48:137–146 © 2000 Society of

Biologi-cal Psychiatry

Key Words: Schizophrenia, neuropsychology, executive

functions, age, deterioration

Introduction

A

central question in schizophrenia is whether the disorder is developmental, degenerative, or both. From the earliest descriptions of schizophrenia by Kraepe-lin (1919), the disorder has generally been considered a deteriorating illness; however, there is limited research confirming the long-held contention that deterioration occurs beyond that found in the first few years of illness (i.e., “dementia praecox”). Moreover, much recent evi-dence supports the hypothesis (e.g., Murray and Lewis 1987; Seidman 1990; Weinberger 1987) that patients with schizophrenia have primary neurodevelopmental etiolo-gies, usually involving obstetric complications, genetic factors, or both. The presence of neurodevelopmental abnormality, however, does not negate the possibility of subsequent deterioration.In this study we evaluate whether neuropsychologic deficits, prominent early in the disorder (Hoff et al 1992; Saykin et al 1994), decline further during the illness. Neuropsychologic impairments associated with schizo-phrenia involve a broad range of functions and appear to be present in most schizophrenic patients (Kremen et al 1999; Levin et al 1989; Palmer et al 1997; Randolph et al 1993; Seidman et al 1992). Impairments in sustained and selective attention, executive functions (i.e., abstract rea-soning, planning, and cognitive flexibility), working ory, motor and psychomotor functions, declarative mem-ory, and olfaction have been documented in schizophrenia. In reviews of the literature, Heaton and Drexler (1988), Seidman (1983), and Goldberg and Seidman (1991) noted little evidence indicating decline in neuropsychologic functioning over time; however, Seidman (1983), based on the few studies then available, summarized the evidence suggesting that if there was a deterioration, the brain system involved was the frontal-executive network. Other From Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Neurology, St.

Louis, Missouri (RF); the Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts Mental Health Center, Boston (LJS, SVF, JMG, MTT), Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry at Brockton/West Roxbury VA Medical Center, Brockton (LJS, SVF, JMG, MTT), Harvard Institute of Psychiatric Epidemiology and Genetics, Boston (LJS, SVF, JMG, MTT), and Harvard School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, Boston (MTT), Massachusetts; and University of California, Davis School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Sacramento and University of California, Davis– Napa Psychiatric Research Center, Napa (WSK).

Address reprint requests to Larry J. Seidman, Ph.D., Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts Mental Health Center, 74 Fenwood Road, Boston MA 02115. Received August 9, 1999; revised January 12, 2000; accepted January 13, 2000.

© 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry 0006-3223/00/$20.00

investigators have suggested that olfaction and executive function, both of which are associated with frontal net-works, may deteriorate more rapidly with age in schizo-phrenia (Moberg et al 1997; Sullivan et al 1994). Compli-cating this view of the relationship of aging and schizophrenia is the possibility that age at disease onset or illness duration may have independent and/or interactive effects on neuropsychologic status.

The neurodegenerative hypothesis has been tested using neuropsychologic, neuroimaging, and electrophysiological techniques. Although this paper will focus on evidence from neuropsychology, it is notable that some longitudinal reports have indicated that frontal lobe volume reductions occur early in the course of the illness and may progress over time (Gur et al 1998). In addition, progressive ventricular enlargement has been documented among subsets of chronic patients (e.g., DeLisi et al 1997), though not consistently. Neuropsychologic studies indicate that there may be at least a subset of patients who demonstrate premature brain degeneration and accelerated cognitive decline (Buchsbaum and Hazlett 1997); however, evi-dence suggests that a substantial portion of patients do not decline beyond an initial deterioration of cognitive func-tion that apparently occurs during the first 5 years of illness (Bilder et al 1992; Heaton and Drexler 1988). Several longitudinal studies have observed no overall decline in global cognitive functioning over 8 month to 5-year periods (Harvey et al 1990, 1995; Sweeney et al 1991; Waddington et al 1990). In a recent review of 15 longitudinal studies of neuropsychologic function in schizophrenia, Rund (1998) concluded that cognitive def-icits are relatively stable over the course of the illness; however, the conclusions reached are limited by the variable ages, phases of illness, and length of follow-up periods used in these studies. In contrast to most longitu-dinal reports, Harvey et al (1999) recently demonstrated that a significant subset of chronically institutionalized, older patients with schizophrenia exhibited detectable declines in cognitive and functional status over a longer 30-month study period in old age.

The majority of cross-sectional studies of age-related neuropsychologic change also find little evidence of de-cline (Chen et al 1996; Goldberg et al 1993; Hyde et al 1994; Kremen 1990; Mockler et al 1997), though not all concur (Bilder et al 1992; Davidson et al 1995). Davidson et al (1995) found a slight decline with increasing age on mental status examination scores in a sample of very ill schizophrenia patients (ages 25–95) with low mental status scores overall, compared to control subjects (mean Mini-Mental Status score was 9.6); however, age-related differences in patients with schizophrenia may disappear when the effects of normal aging are accounted for (Heaton et al 1994). Chen et al (1996) studied a large

group of patients aged 16 to 65 and found similar age-related effects on neuropsychologic performance in comparison to healthy control subjects when looking at patients with varying disease durations. Mockler et al (1997) found no evidence of deterioration in intelligence or memory functioning with age in schizophrenic patients (at least to age 69). Finally, Hyde et al (1994) studied five cohorts of patients using neuropsychologic measures of naming, verbal learning and fluency, as well as a global dementia rating scale and a mental status examination, and found no evidence of decline across age groups. As with the Mockler et al (1997) report mentioned above, how-ever, a control group was not included. In sum, most, but not all, of the cross-sectional reports are consistent with the longitudinal studies indicating that little if any deteri-oration occurs with advanced age in most patient with schizophrenia, beyond that which would be expected with normal aging. It is important to note, however, that most reports indicating no decline with old age in schizophrenia studied relatively young elderly patients (younger than age 70).

Several methodological issues have limited the interpre-tation of previous studies of neuropsychologic decline in schizophrenia. Longitudinal studies suffer from short fol-low-up periods, variable folfol-low-up intervals, and a limited range of instruments. Cross-sectional studies in particular have been limited by the absence of appropriate age-matched control groups. Moreover, few studies have considered the possible confound of age of onset. Finally, the selection of neurocognitive functions measured may have an influence on the identification of an age-related effect in schizophrenia. There is some evidence that a younger age of onset and longer disease duration are associated with greater impairment in executive function-ing (i.e., abstraction/cognitive flexibility) (Albus et al 1996; Sullivan et al 1994). For example, Sweeney et al (1992) compared young first-episode and young patients with multiple episodes on neuropsychologic measures and found greater impairment in patients with multiple epi-sodes on tests of frontal lobe function and verbal memory, suggesting the possibility of progressive decline in these functions with more frequent episodes. Kremen et al (1999) suggested that age of onset is related to neuropsy-chologic function based on the observation that schizo-phrenia patients with relatively normal neuropsychologic profiles had a later onset of illness than those with abnormal profiles. Some recent work, however, suggests that age at disease onset and duration of illness may be unrelated to neuropsychologic functioning (Chen et al 1996; Heaton et al 1994), indicating that more research is needed to answer this question.

neuropsychologic functioning among a large sample of patients with schizophrenia and healthy control subjects. An extensive battery of neuropsychologic tests was uti-lized to permit the assessment of a wide range of neuro-cognitive functions, including assessment of executive functions. We hypothesized that similar age-related reduc-tions in cognitive performance would be detected in patients and control subjects based on earlier cross-sectional work, but that if age-related declines were present, they would be detected on measures of executive function. We also examined the impact of age of onset on the relationship between age and neuropsychologic function.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

All participants (87 patients with schizophrenia, 94 healthy control subjects) gave informed consent and were paid for their participation in this study. Patients were recruited from three Boston-area public hospitals specializing in the treatment of chronic mental illness. Inclusion criteria for patients were a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the DSM-III-R (Amer-ican Psychiatric Association 1987), age between 18 and 75, English as the primary language, and a minimum of 8 years of formal education. Exclusion criteria included neurologic disease or damage, current substance abuse (within the past 6 months), history of head injury with loss of consciousness greater than 5 minutes or with documented neurocognitive sequelae, mental retardation, and medical illnesses associated with significant cognitive dysfunction.

The mean number of hospitalizations was 7.8 (SD55.2), with a mean lifetime length of hospitalization of 72.6 (SD572.0) months. The mean age at first hospitalization was 24.0 (SD5

6.4) years. At the time of testing, 66% of the patients were outpatients (n557) and 34% were inpatients (n530). Patients were generally tested while on antipsychotic medications (mean

dosage in chlorpromazine equivalents 5 634.8; SD5 589.4), and while clinically stable (see Table 1 for demographics). Fifty-one of the patients with schizophrenia (59%) were taking anticholinergic medication. SANS and SAPS (Scales for the Assessment of Negative and Positive Symptoms; Andreasen and Olsen 1982) global scores were grouped into the three factors typically found when these scores have been factor-analyzed: Negative Symptoms, Positive Symptoms (“Reality Distortion”), and Disorganization factors (Toomey et al 1997). Schizophrenia patients for whom clinical data was available (n 5 56) had a mean Negative Symptom score of 1.8161.0, a Reality Distor-tion score of 2.0761.5, and a Disorganization score of 1.386

1.0.

Healthy control subjects (n 5 94) were recruited through advertisements placed in the community and from among the nonprofessional hospital staffs. With the exception of presence of current psychopathology or family history of psychosis, selection criteria were the same as for patients. In place of a diagnostic interview, a short form of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-168; Vincent et al 1984) was used to screen control subjects for current psychopathology. Further details about ascertainment of control subjects are provided in previous reports (Faraone et al 1995; Kremen et al 1996).

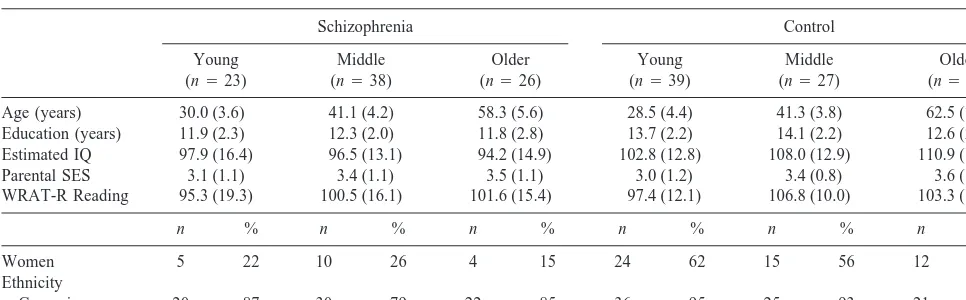

Control subjects were similar to patients in age, ethnicity, single word reading ability (Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised), and parental socioeconomic status. As can be seen in Table 1, control subjects had more years of education and higher IQ estimates (based on age-scaled Vocabulary and Block Design scores; Brooker and Cyr 1986) than patients, as expected; however, the performance of the control subjects on estimated IQ and reading ability were solidly in the average range. Moreover, the six groups were matched on reading ability, which we and others have argued is an appropriate way to match schizophrenia patients and control subjects (cf., Kremen et al 1996). The patient group overall was composed of significantly more men and fewer women than the control group. Subjects were divided into three age groups: “young” (age 20 –35: 23 schizophrenics, 39 control subjects); “middle” (age 36 – 49: 38 schizophrenics, 27 Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Schizophrenia and Control Subjects by Age Group (Mean and SD)

Schizophrenia Control

Young (n523)

Middle (n538)

Older (n526)

Young (n539)

Middle (n527)

Older (n528)

Age (years) 30.0 (3.6) 41.1 (4.2) 58.3 (5.6) 28.5 (4.4) 41.3 (3.8) 62.5 (7.2)

Education (years) 11.9 (2.3) 12.3 (2.0) 11.8 (2.8) 13.7 (2.2) 14.1 (2.2) 12.6 (2.9) Estimated IQ 97.9 (16.4) 96.5 (13.1) 94.2 (14.9) 102.8 (12.8) 108.0 (12.9) 110.9 (15.8)

Parental SES 3.1 (1.1) 3.4 (1.1) 3.5 (1.1) 3.0 (1.2) 3.4 (0.8) 3.6 (1.1)

WRAT-R Reading 95.3 (19.3) 100.5 (16.1) 101.6 (15.4) 97.4 (12.1) 106.8 (10.0) 103.3 (16.2)

n % n % n % n % n % n %

Women 5 22 10 26 4 15 24 62 15 56 12 43

Ethnicity

Caucasian 20 87 30 79 22 85 36 95 25 93 21 78

Significant group differences were found for gender [Pearsonx2(5)523.22, p,.001]. Within each diagnostic group, participants were not significantly different on

control subjects); and “older” (age 50 –75: 26 schizophrenics, 28 control subjects). The six cohorts of patients and control subjects (three age cohorts per group) were not significantly different on reading ability and parental socioeconomic status (all Fs,2.0). Differences between patient groups were found on age at first hospitalization, with the oldest cohort (mean527.5; SD56.5 years) showing an older age at first hospitalization compared to the young group [mean521.3; SD54.4years; t(46)5 1.61,

p, .0001]. Middle patients did not differ significantly from either group in age at first hospitalization (mean523.4; SD5

6.4 years). Because of the possibility that age of first hospital-ization (a possible indicator of disease severity) could account for any age-related changes detected, we analyzed the data with and without adjustment for age at first hospitalization.

Procedure

Trained research assistants interviewed patients with the Sched-ule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS; Spitzer and Endicott 1978), with the Scales for the Assessment of Negative and Positive Symptoms (Andreasen and Olsen 1982), reviewed all medical records, and conferred with treating physi-cians. At least two psychologists and/or psychiatrists reviewed all available information to determine consensus lifetime DSM-III-R diagnoses.

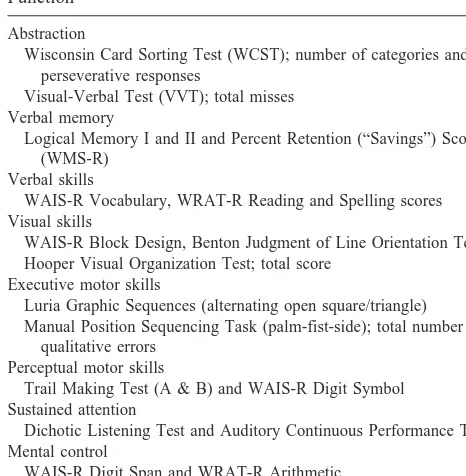

Trained examiners administered an extensive neuropsycho-logic test battery that involved about 6 – 8 hours of testing. The test battery is presented in Table 2 with tests grouped by function and is described in detail elsewhere (cf., Faraone et al 1995; Lezak 1995). Grouping of neuropsychologic tests into function scores was also based on previous factor-analytic studies (Kre-men et al 1992; Mirsky et al 1991). It should be noted that the

dichotic listening measure was the total digits apprehended (regardless of which ear the subject identified s/he heard the digits) in both ears over 48 trials (cf. Seidman et al 1993) rather than the 24 trials used to study relatives of schizophrenic patients (Faraone et al 1995). Each trial consisted of strings of three digits presented simultaneously to each ear (Kimura 1967) at an equal intensity (80 dB). Percent retention of verbal memory passages was delayed recall divided by immediate recall3100 (described in Seidman et al 1998). The Wisconsin Card Sort (WCST) was the original 128 card, noncomputerized version used in all of our studies (Heaton 1981; Koren et al 1998).

Data Analysis

First, raw test scores on each test in Table 5 were transformed to

Z scores (mean50; SD51). Standardization of these individual raw scores (to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1) was completed using the control mean and the pooled standard deviation within all groups (i.e., root mean square error). Second, composite function scores were created by averaging Z scores within each theoretical domain.

Pearson product-moment correlations were used first to exam-ine the association between age and each of the eight function scores in each group (schizophrenia patients and control sub-jects). We used Fisher’s r-to-Z transformation to test for be-tween-group differences for each set of correlations. To deter-mine whether age at first hospitalization influenced age-related changes in neuropsychologic performance, partial correlations between age and the eight function scores were also calculated (controlling for age at first hospitalization). The groups were each subdivided into three roughly equal size subgroups, in part, because performance patterns in some subgroups could be obscured by using simple correlations. Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was then used with diagnosis (pa-tients, control subjects) and age group (young, middle-aged, older) as the between-group factors, and the eight neuropsycho-logic composite function scores as the dependent variables. Gender was included as a covariate because of the significant difference in the gender distribution between patients and control subjects. This was followed by within-group contrasts on each function.

Results

Correlations of Age with Neuropsychologic Function Scores

Zero-order Pearson correlations of age with each of the eight function scores for each group are shown in Table 3. Among patients with schizophrenia, increasing age was associated with significantly decreased performance on Abstraction, Visual Skills, and Perceptual Motor Skills functions. Among control subjects, increasing age was also associated with decreased performance on the Ab-straction, Visual Skills, and Perceptual Motor Skills func-tions, as well as on the Memory, Executive Motor, and Sustained Attention functions. No group differences were

Table 2. Neuropsychologic Battery of Tests Grouped by Function

Abstraction

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST); number of categories and perseverative responses

Visual-Verbal Test (VVT); total misses Verbal memory

Logical Memory I and II and Percent Retention (“Savings”) Score (WMS-R)

Verbal skills

WAIS-R Vocabulary, WRAT-R Reading and Spelling scores Visual skills

WAIS-R Block Design, Benton Judgment of Line Orientation Test, Hooper Visual Organization Test; total score

Executive motor skills

Luria Graphic Sequences (alternating open square/triangle) Manual Position Sequencing Task (palm-fist-side); total number of

qualitative errors Perceptual motor skills

Trail Making Test (A & B) and WAIS-R Digit Symbol Sustained attention

Dichotic Listening Test and Auditory Continuous Performance Test Mental control

WAIS-R Digit Span and WRAT-R Arithmetic

observed in correlations between age and function scores with the exception of the Verbal Memory function in which control subjects exhibited a significantly stronger association.

Indicators of disease severity may obscure interpreta-tion of age-related declines, because differences along such variables may reflect cohort effects (i.e., an older age at first hospitalization may reflect a less severe illness and/or limited access to psychiatric resources; Kremen 1990). Indeed, age was positively correlated with age at first hospitalization in our sample of schizophrenics (r5 .43, p , .0001), indicating that our oldest patients (ages 50 –75) were older at their first hospitalization compared to middle and younger patients. Furthermore, significant correlations were found between age at first hospitaliza-tion and the Verbal Skills, Executive Motor Skills, Mental Control, and Sustained Attention function scores in the patients (all ps ,.02). We calculated partial correlations between age and each of the eight function scores

control-ling for age at first hospitalization among the schizophren-ics to see if the zero-order correlations discussed above remained significant. Results indicated that the negative correlations between age and Abstraction, Visual Skills, and Perceptual Motor Skills remained significant (and were stronger) when the effects of age at first hospitaliza-tion were controlled (r5 2.47, r5 2.38, and r5 2.50, respectively). There were no significant associations be-tween the three symptom dimensions (derived from the SANS and SAPS), age, and the eight neuropsychologic functions in the patients with schizophrenia (all rs,.21, all ps..20).

Multivariate Analysis of Age Effects on Neuropsychologic Function Scores

Figure 1 plots the neuropsychologic profiles of the patients with schizophrenia (graph on the left) and control subjects (graph on the right) according to age group (young, middle, and older). Schizophrenic patients scored lower than control subjects across all neuropsychologic func-tions except the Verbal Function [F(1,161)5 21.63, p, .0001]. This main effect can be seen in Figure 1 (the profiles for all patient groups lie below the mean of zero). A significant multivariate age group3diagnosis interac-tion was also detected [F(2,161) 5 1.86, p 5 .02]; however, the only significant univariate age group 3 diagnosis interaction was on Abstraction [F(2,161) 5 3.29, p5.040; see Figure 1], in which the oldest patients had significantly worse deficits in functioning. This two-way interaction remained significant when neuroleptic dose was controlled statistically (p 5 .042), and when patients on anticholinergic medications were excluded from the analysis (p5.037). The magnitude of difference

Table 3. Pearson Correlations of Age and Neuropsychologic Function Scores by Group

Function Schizophrenia Control

Abstraction 20.31b 20.32b ns

Verbal memory 20.13 20.47b c

Verbal skills 0.08 0.05 ns

Visual skills 20.32b 20.30b ns

Executive motor skills 20.01 20.24a ns

Perceptual motor skills 20.39b 20.53b ns

Mental control 20.05 20.08 ns

Sustained attention 20.01 20.29a ns

ap,.05. bp,.005.

cA significant difference was found between groups on correlations of Verbal

Memory and age (t5 22.51, p,.05).

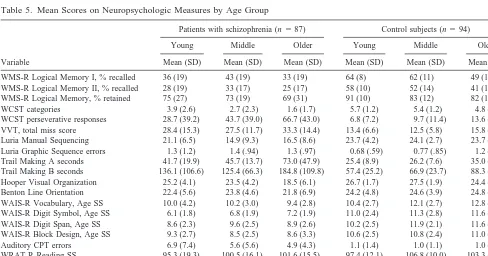

between the youngest and the oldest age groups was approximately 1.0 SD in patients, versus 0.4 SD in control subjects. This was accounted for by lower performance on the WCST rather than by conceptual impairment on the Visual Verbal Test (VVT; Feldman and Drasgow 1981) (see Table 4 and discussion below). Although visual

inspection of the profile levels in Figure 1 suggests strong age-related declines in Perceptual Motor Skills (particu-larly in the oldest schizophrenics), statistical differences in the magnitude of age-related decline were not found between patients and control subjects. For descriptive purposes only, mean scores (including age-scaled scores for Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised and Wide Range Achievement Test—Revised scores) on all neuro-psychologic measures, for each age sub-group, are pre-sented in Table 5.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional investigation of the effects of aging on neuropsychologic function in patients with schizophre-nia, similar patterns of age effects on neuropsychologic functions were observed in patients and healthy control subjects, with the exception of significantly greater age-related declines in abstraction functions among the pa-tients, observed when the patients and control subjects were subdivided into three age groups (“young,” “mid-dle,” “older”). The decline in abstraction is consistent with some previous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies using electrophysiological and neuropsychologic mea-sures (O’Donnell et al 1995; Sullivan et al 1994).

Correlational analyses revealed similarly significant age-related declines on most functions in patients and in

Table 4. Performance on Abstraction Function by Age Group (Mean Z score1SD): WCST and VVT Variables

Group

WCST-Categories (Mean6SD)

WCST-PR (Mean6SD)

VVT (Mean6SD)

Schizophrenia

Young (n523) 20.7061.29a 20.6461.32a 21.3361.41

Middle (n538) 21.3361.17 21.1561.32a 21.2561.08

Older (n526) 21.8460.86 21.9361.45 21.7961.33 Control

Young (n539) 0.1760.57b 0.1060.24b 0.0460.61

Middle (n527) 0.0360.61 0.0060.38 0.1260.53 Older (n528) 20.2660.96 20.1360.50 0.1860.68

VVT (Visual-Verbal Test) scores are Total Miss Score (Feldman and Drasgow 1981). WCST-PR is number of perseverative responses on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test task. Z scores have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.0. All three variables are scored in the same direction (minus is worse performance).

aSignificant differences were found between young and older patients with

schizophrenia on WCST categories [t(36)53.49, p5.001] and perseverations [t(45)5 23.17, p5.003], but not VVT score. Middle-aged patients differed from older patients on WCST perseverations only [t(48)5 22.15, p5.037].

bSignificant differences were found between younger and older controls on

WCST categories [t(41)52.13, p5.039] and perseverations [t(37)5 22.26, p5

.030], but not VVT score.

Table 5. Mean Scores on Neuropsychologic Measures by Age Group

Variable

Patients with schizophrenia (n587) Control subjects (n594)

Young Middle Older Young Middle Older

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD)

WMS-R Logical Memory I, % recalled 36 (19) 43 (19) 33 (19) 64 (8) 62 (11) 49 (12)

WMS-R Logical Memory II, % recalled 28 (19) 33 (17) 25 (17) 58 (10) 52 (14) 41 (13)

WMS-R Logical Memory, % retained 75 (27) 73 (19) 69 (31) 91 (10) 83 (12) 82 (18)

WCST categories 3.9 (2.6) 2.7 (2.3) 1.6 (1.7) 5.7 (1.2) 5.4 (1.2) 4.8 (1.9)

WCST perseverative responses 28.7 (39.2) 43.7 (39.0) 66.7 (43.0) 6.8 (7.2) 9.7 (11.4) 13.6 (14.8) VVT, total miss score 28.4 (15.3) 27.5 (11.7) 33.3 (14.4) 13.4 (6.6) 12.5 (5.8) 15.8 (7.3) Luria Manual Sequencing 21.1 (6.5) 14.9 (9.3) 16.5 (8.6) 23.7 (4.2) 24.1 (2.7) 23.7 (4.3) Luria Graphic Sequence errors 1.3 (1.2) 1.4 (.94) 1.3 (.97) 0.68 (.59) 0.77 (.85) 1.2 (.85) Trail Making A seconds 41.7 (19.9) 45.7 (13.7) 73.0 (47.9) 25.4 (8.9) 26.2 (7.6) 35.0 (17.1) Trail Making B seconds 136.1 (106.6) 125.4 (66.3) 184.8 (109.8) 57.4 (25.2) 66.9 (23.7) 88.3 (43.0) Hooper Visual Organization 25.2 (4.1) 23.5 (4.2) 18.5 (6.1) 26.7 (1.7) 27.5 (1.9) 24.4 (3.6) Benton Line Orientation 22.4 (5.6) 23.8 (4.6) 21.8 (6.9) 24.2 (4.8) 24.6 (3.9) 24.8 (4.2) WAIS-R Vocabulary, Age SS 10.0 (4.2) 10.2 (3.0) 9.4 (2.8) 10.4 (2.7) 12.1 (2.7) 12.8 (4.3) WAIS-R Digit Symbol, Age SS 6.1 (1.8) 6.8 (1.9) 7.2 (1.9) 11.0 (2.4) 11.3 (2.8) 11.6 (2.5) WAIS-R Digit Span, Age SS 8.6 (2.3) 9.6 (2.5) 8.9 (2.6) 10.2 (2.5) 11.9 (2.1) 11.6 (2.4) WAIS-R Block Design, Age SS 9.3 (2.7) 8.5 (2.5) 8.6 (3.3) 10.6 (2.5) 10.8 (2.4) 11.0 (2.4)

Auditory CPT errors 6.9 (7.4) 5.6 (5.6) 4.9 (4.3) 1.1 (1.4) 1.0 (1.1) 1.0 (1.5)

WRAT-R Reading SS 95.3 (19.3) 100.5 (16.1) 101.6 (15.5) 97.4 (12.1) 106.8 (10.0) 103.3 (6.2) WRAT-R Spelling SS 91.8 (21.2) 99.8 (17.3) 105.0 (17.3) 98.7 (12.5) 102.5 (13.8) 99.7 (18.5) WRAT-R Arithmetic SS 82.0 (14.6) 88.8 (16.2) 90.6 (13.7) 92.0 (12.3) 102.3 (15.1) 97.9 (18.5)

WAIS-R and WRAT-R scores in this table are age-scaled scores presented for descriptive purposes only (raw scores were used for statistical analyses).

control subjects, with the exception of the Verbal Memory function, in which control subjects demonstrated a stron-ger association with age than patients. The significant correlations between age and the Executive Motor, Verbal Memory, and Sustained Attention functions found in control subjects were not observed for patients perhaps because deficits in these areas occurred early in the disease process (i.e., earlier onset of cognitive deficit), though this hypothesis is speculative and needs empirical support. The significant association between age and the Abstraction function was not attenuated when the effects of age at first hospitalization (a possible confound and indicator of disease severity) was controlled. Differences between the groups could not be attributed to any gender differences as this was controlled in the analyses.

Multivariate analyses confirmed that although patients with schizophrenia performed at lower levels than control subjects on all functions (except the Verbal function), the magnitude of age-related declines on most functions was similar in both groups. This was consistent with most other studies demonstrating that neuropsychologic functions do not decline significantly in most patients after the early years of the illness, but are vulnerable to the same effects of normal aging as those of healthy adults (Goldberg et al 1993; Harvey et al 1995; Hyde et al 1994; Rund 1998; Seidman 1983; Weinberger 1987). Recently, Goldstein et al (1998) reported similar correlations between age and a global index of cognitive functioning among mildly im-paired patients with schizophrenia, patients with progres-sive dementias and control subjects; however, consistent with our results, a more severely impaired subset of schizophrenia patients showed no significant associations between age and the impairment index, indicating early and substantial cognitive loss in some patients which may be nonprogressive.

Consistent with speculations by Seidman (1983), we found evidence of significantly greater decline in execu-tive functions (in the Abstraction function) among the patients with schizophrenia, when the groups were subdi-vided into three roughly equal size age groups. The greater decline in Abstraction in patients with schizophrenia than in control subjects, in the MANCOVA as compared to the correlational analyses, reflects functioning in different age defined subgroups of patients obscured by simple corre-lations within the entire group. The magnitude of the difference between diagnostic groups was approximately 0.6 SD. Furthermore, this finding could not be accounted for by antipsychotic medication dose (in chlorpromazine equivalents), anticholinergic medication, or the later age at first hospitalization of our oldest group of patients. Clin-ical symptoms as measured by the SANS and SAPS were not significantly correlated with age or any of the eight neuropsychologic function scores, indicating that positive

and negative symptomatology could not account for the age-related decline found in our sample.

It is notable that later age at first hospitalization in the older group would tend to reduce the difference. Sullivan et al (1994) reported a relationship between age at first hospitalization and executive functioning in schizophrenic patients which could account for “selective” age-related declines in these functions. In our sample, however, age at first hospitalization was not correlated with the Abstrac-tion funcAbstrac-tion in patients, and the difference in rate of decline in Abstraction between schizophrenic patients and control subjects remained significant after controlling for age at first hospitalization. As seen in Table 4, the age-related decline observed in patients on VVT perfor-mance was substantially smaller than on the WCST, and significant differences were not found on the VVT be-tween age groups among patients or control subjects. In contrast, age-group differences were detected on both WCST variables among patients and control subjects (Table 4). Thus, the accelerated decline detected in the Abstraction function among patients appeared to be ac-counted for largely by performance on the WCST.

brains. This interpretation is speculative and awaits direct empirical test.

Strengths of the present study include use of a large group of patients and well-matched control subjects, a comprehensive neuropsychologic battery of tests, includ-ing measures of executive functions, and a wide age range of subjects; however, there are several limitations to the study, which merit consideration. First, cross-sectional studies are sensitive to cohort effects that may confound differential effects of age on performance. We found a relationship between age of onset and age in our sample, but controlling for this variable did not diminish age-related declines. Longitudinal studies over longer time periods that utilize comprehensive neuropsychologic bat-teries would provide definitive data. Second, we did not study the “very” old patients with schizophrenia (older than 75 years of age), and thus it is not clear whether similar effects of aging would be observed in an older group. Third, our patients were recruited from hospitals that specialize in the treatment of chronically psychotic people. Thus, results may not generalize to other sub-groups of patients (although about 65% were outpatients). Moreover, our older patient group was not necessarily a more severely impaired subgroup, because their single word oral reading scores (a premorbid matching variable) were actually higher than that of the older control subjects. Thus, despite average premorbid intellectual ability, these patients showed the largest relative decline with age on some executive functions. Finally, although gender was used as a covariate in all analyses, the results may not generalize to female patients with schizophrenia, given the relatively small representation of women in the current sample. Future studies should include larger samples of female patients to address any interaction between cogni-tive functioning, age and gender (Goldstein et al 1998).

In summary, similar age-related declines on most neu-ropsychologic functions were observed in patients with schizophrenia and control subjects, indicating that most patients do not show a progressive, widespread “dement-ing” course later in the illness. We did find evidence, however, of larger patient-control differences in some higher-order executive functions among the older subjects, as reflected in Wisconsin Card Sorting deficits, which may reflect deterioration of frontal system networks in older patients with schizophrenia. The possibility that there is another phase of deterioration in old age in patients with schizophrenia, long after the decline observed in the first few years of illness, is a hypothesis worthy of further study.

Preparation of this article was supported in part by an award from the NARSAD Foundation to Dr. Robert Fucetola, National Institute of Mental Health Grants No. MH 43518 and No. MH 46318 to Dr. Ming T.

Tsuang, Stanley and NARSAD Foundation Awards to Dr. Larry J. Seidman, and National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. SDA K21 MH 00976 to Dr. Jill M. Goldstein.

The authors thank the following people for their contributions to this project: Gwen Barnes, Mimi Braude, Deborah Catt, Joanne Donatelli, Tova Ferro, Lisa Gabel, David Goldfinger, Robin Green, Dr. Keith Hawkins, Lynda Jacobs, Denise Leville, Dr. Michael Lyons, Catherine Monaco, Dr. Theresa Pai, Dr. John Pepple, Anne Shore, Dr. Rosemary Toomey, Jason Tourville, Rob Trachtenberg, and Judith Wides.

This work was presented, in part, as a paper at the annual meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society, February 10 –13, 1999, Boston.

References

Albus M, Hubmann W, Ehrenberg C, Forcht U, Mohr F, Sobizack N, et al (1996): Neuropsychological impairment in first-episode and chronic schizophrenic patients. Eur Arch

Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 246:249 –255.

American Psychiatric Association (1987): Diagnostic and

Sta-tistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed rev. Washington,

DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Andreasen NC, Olsen S (1982): Negative v. positive schizophre-nia. Definition and validation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39:789 – 794.

Bilder RM, Lipschutz-Broch L, Reiter G, Geisler SH, Mayerhoff DL, Lieberman JA (1992): Intellectual deficits in first-episode schizophrenia: Evidence for a progressive deteriora-tion. Schizophr Bull 18:437– 448.

Brooker BH, Cyr JJ (1986): Tables for clinicians to use to convert WAIS-R short forms. J Clin Psychol 42:983–986. Buchsbaum MS, Hazlett EA (1997): Functional brain imaging

and aging in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 27:129 –141. Chen EYH, Lam LCW, Chen RYL, Nguyen DGH, Chan CKY

(1996): Prefrontal neuropsychological impairment and illness duration in schizophrenia: A study of 204 patients in Hong Kong. Acta Psychiatr Scand 93:144 –150.

Davidson M, Harvey PD, Parrella M, White L, Knobler HY, Losonczy MF, et al (1995): Severity of symptoms in chron-ically institutionalized geriatric schizophrenic patients. Am J

Psychiatry 152:197–207.

DeLisi LE, Sakuma M, Tew W, Kushner M, Hoff AL, Grimson R (1997): Schizophrenia as a chronic active brain process: A study of progressive brain structural change subsequent to the onset of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 74:129 –140. Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Pepple JR, Lyons MJ,

Tsuang MT (1995): Neuropsychological functioning among the nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients: A diag-nostic efficiency analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 104:286 –304. Feldman MJ, Drasgow J (1981): The Visual-Verbal Test. Los

Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Goldberg E, Seidman LJ (1991): Higher cortical functions in normals and in schizophrenia: A selective review. In: Stein-hauer S, Gruzelier J, Zubin J, editors. Handbook of

Schizo-phrenia, Vol. 5: Neuropsychology, Psychophysiology and Information Processing. New York: Elsevier, 553–597.

Goldman-Rakic, PS (1991): Prefrontal cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia: The relevance of working memory. In: Carroll BJ, Barret JE, editors. Psychopathology and the Brain. New York: Raven, 1–23.

Goldstein G, Allen DN, van Kammen DP (1998): Individual differences in cognitive decline in schizophrenia. Am J

Psychiatry 155:1117–1118.

Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Goodman JM, Koren D, Lee H, Weintraub S, et al (1998): Are there sex differences in neuropsychological functions among schizophrenia patients? Results from a case control study. Am J Psychiatry 155: 1358 –1364.

Gur RE, Cowell P, Turetsky BI, Gallacher F, Cannon T, Bilker W, et al (1998): A follow-up magnetic resonance imaging study of schizophrenia: Relationship of neuroanatomical changes to clinical and neurobehavioral measures. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 55:145–152.

Harvey PD, Docherty NM, Serper MR, Rasmussen M (1990): Cognitive deficits and thought disorder: II. An eight month follow-up study. Schizophr Bull 16:147–156.

Harvey PD, Silverman JM, Mohs RC, Parrella M, White L, Powchik P, et al (1999): Cognitive decline in late-life schizophrenia: A longitudinal study of geriatric chronically hospitalized patients. Biol Psychiatry 45:32– 40.

Harvey PD, White L, Parrella M, Putnam KM, Kincaid MM, Powchik P, et al (1995): The longitudinal stability of cogni-tive impairment in schizophrenia: Mini-Mental State scores at one- and two-year follow-ups in geriatric inpatients. Br J

Psychiatry 166:630 – 633.

Heaton R, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, et al (1994): Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics: Relationship to age, chronicity and dementia. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 51:469 – 476.

Heaton RK (1981): The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Heaton RK, Drexler M (1988): Clinical neuropsychological findings in schizophrenia and aging. In: Miller NE, Cohen GD, editors. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America:

Psychosis and Depression in the Elderly. Philadelphia:

Saun-ders, 15–32.

Hoff AL, Riordan H, O’Donnell D, Stritzke P, Neale C, Boccio A, et al (1992): Anomalous lateral sulcus asymmetry and cognitive function in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr

Bull 18: 257–270.

Hyde TM, Nawroz S, Goldberg TE, Bigelow LB, Strong D, Ostrem JL, et al (1994): Is there cognitive decline in schizo-phrenia: a cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry 164:494 – 500.

Kimura D (1967): Functional asymmetry of the brain in dichotic listening. Cortex 3:163–178.

Koren D, Seidman LJ, Harrison RH, Lyons MJ, Kremen WS, Caplan BB, et al (1998): Factor structure of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: Dimensions of deficit in schizophrenia.

Neuropsychology 12:289 –302.

Kraepelin E (1919): Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Edin-burgh, UK: E & S Livingstone.

Kremen WS (1990): Age and neuropsychological functioning in DSM-III-R schizophrenia (Doctoral dissertation, Boston Uni-versity). Dissertation Abstr Int 51: 991B. (University Micro-films No. ADG90 –17583, 9000)

Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Pepple JR, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT (1996): The “3 Rs” and neuropsychological function in schizophrenia: An empirical test of the matching fallacy. Neuropsychology 10:22–31.

Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Pepple JR, Tsuang MT (1992): Attention/information-processing factors in psychotic disorders: Replication and extension of recent neuropsycho-logical findings. J Nerv Ment Dis 180:89 –93.

Kremen WR, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Toomey R, Tsuang MT (1999): The question of neuropsychologically normal schizo-phrenia. Schizophr Res 36:140 –141.

Levin S, Yurgelun-Todd D, Craft S (1989): Contributions of clinical neuropsychology to the study of schizophrenia. J

Abnorm Psychol 98:341–356.

Lezak MD (1995): Neuropsychological Assessment, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mirsky AF, Anthony BJ, Duncan CC, Ahearn MB, Kellam SG (1991): Analysis of the elements of attention: A neuropsy-chological approach. Neuropsychol Rev 2:109 –145. Moberg PJ, Doty RL, Turetsky BI, Arnold SE, Mahr RN, Gur

RC, et al (1997): Olfactory identification deficits in schizo-phrenia: Correlation with duration of illness. Am J Psychiatry 154:1016 –1018.

Mockler D, Riordan J, Sharma T (1997): Memory and intellec-tual deficits do not decline with age in schizophrenia.

Schizo-phr Res 26:1–7.

Murray RM, Lewis SW (1987): Is schizophrenia a neurodevel-opmental disorder? BMJ 295:681– 682.

O’Donnell BF, Faux SF, McCarley RW, Kimble MO, Salisbury DF, Nestor PG, et al (1995): Increased rate of P300 latency prolongation with age in schizophrenia. Electrophysiological evidence for a neurodegenerative process. Arch Gen

Psychi-atry 52:544 –549.

Palmer BW, Heaton RK, Paulsen JS, Kuck J, Braff D, Harris MJ, et al (1997): Is it possible to be schizophrenic yet neuropsy-chologically normal? Neuropsychology 11:437– 446. Randolph C, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR (1993): The

neuro-psychology of schizophrenia. In: Heilman KM, Valenstein E, editors. Clinical Neuropsychology. New York: Oxford Uni-versity Press, 499 –522.

Raz N, Gunning FM, Head D, Dupuis JH, McQuain J, Briggs SD, et al (1997): Selective aging of the human cerebral cortex observed in vivo: Differential vulnerability of the prefrontal gray matter. Cereb Cortex 7:268 –282.

Rund BR (1998): A review of longitudinal studies of cognitive functions in schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull 24:425– 435.

Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Kester DB, Mozley LH, Stafiniak P, et al (1994): Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 51:124 –131.

Seidman LJ (1983): Schizophrenia and brain dysfunction: An integration of recent neurodiagnostic findings. Psychol Bull 94:195–238.

Seidman LJ (1990): The neuropsychology of schizophrenia: A neurodevelopmental and case study approach. J

Neuropsychi-atry 2:301–312.

Clinical Syndromes in Adult Neuropsychology: The Practic-tioner’s Handbook. New York: Elsevier, 381– 449.

Seidman LJ, Pepple JR, Faraone SV, Kremen WS, Green AI, Brown WA, et al (1993): Neuropsychological performance in chronic schizophrenia in response to neuroleptic dose reduc-tion. Biol Psychiatry 33:575–584.

Seidman LJ, Stone WS, Jones R, Harrison RH, Mirsky AF (1998): Comparative effects of schizophrenia and temporal lobe epilepsy on memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 4:342–352. Siegel BV, Reynolds C, Lohr JB, Nuechterlein KH, Bracha HS, Potkin SG, et al (1994): Changes in regional cerebral meta-bolic rate with age in schizophrenics and normal adults. Dev

Brain Dysfunct 7:132–146.

Spitzer RL, Endicott J (1978): Schedule for Affective Disorders

and Schizophrenia, 3rd ed. New York: New York State

Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research.

Sullivan EV, Shear PK, Zipursky RB, Sagar HJ, Pfefferbaum A (1994): A deficit profile of executive, memory, and motor functions in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 36:641– 653. Sweeney JA, Haas GL, Keilp JG, Long M (1991): Evaluation of

the stability of neuropsychological functioning after acute episodes of schizophrenia: A one-year follow-up study.

Psy-chiatry Res 38:63–76.

Sweeney JA, Haas GL, Li S (1992): Neuropsychological and eye movement abnormalities in first-episode and chronic schizo-phrenia. Schizophr Bull 18:283–293.

Toomey RT, Kremen WS, Simpson JC, Samson JA, Seidman LJ, Lyons MJ, et al (1997): Revisiting the factor structure for positive and negative symptoms: Evidence from a large heterogenous psychiatric sample. Am J Psychiatry 154:371– 377.

Vincent KR, Castillo IM, Hauser RI, Zapata JA, Stuart HJ, Cohn CK, et al (1984): MMPI-168 Codebook. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Waddington JL, Youssef HA, Kinsella A (1990): Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia followed up over 5 years, and its longitudinal relationship to the emergence of tardive dyski-nesia. Psychol Med 20:835– 842.

Weinberger DR (1987): Implications of normal brain develop-ment for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen

Psy-chiatry 44:660 – 690.

Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Zec RF (1986): Physiologic dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. I. Regional cerebral blood flow evidence. Arch Gen